Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

| Lung | |

|---|---|

Diagram of the human lungs with the respiratory tract visible, and different colours for each lobe | |

The human lungs flank the heart and great vessels in the chest cavity. | |

| Details | |

| System | Respiratory system |

| Artery | Pulmonary artery |

| Vein | Pulmonary vein |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | pulmo |

| Greek | πνεύμων (pneumon) |

| MeSH | D008168 |

| TA98 | A06.5.01.001 |

| TA2 | 3265 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

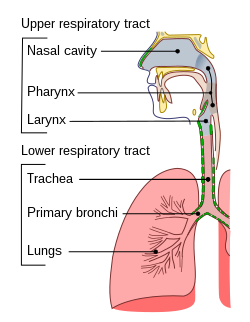

The lungs are the primary organs of the respiratory system in many animals, including humans. In mammals and most other tetrapods, two lungs are located near the backbone on either side of the heart. Their function in the respiratory system is to extract oxygen from the atmosphere and transfer it into the bloodstream, and to release carbon dioxide from the bloodstream into the atmosphere, in a process of gas exchange. Respiration is driven by different muscular systems in different species. Mammals, reptiles and birds use their musculoskeletal systems to support and foster breathing. In early tetrapods, air was driven into the lungs by the pharyngeal muscles via buccal pumping, a mechanism still seen in amphibians. In humans, the primary muscle that drives breathing is the diaphragm. The lungs also provide airflow that makes vocalisation including speech possible.

Humans have two lungs, a right lung and a left lung. They are situated within the thoracic cavity of the chest. The right lung is bigger than the left, and the left lung shares space in the chest with the heart. The lungs together weigh approximately 1.3 kilograms (2.9 lb), and the right is heavier. The lungs are part of the lower respiratory tract that begins at the trachea and branches into the bronchi and bronchioles, which receive air breathed in via the conducting zone. These divide until air reaches microscopic alveoli, where gas exchange takes place. Together, the lungs contain approximately 2,400 kilometers (1,500 mi) of airways and 300 to 500 million alveoli. Each lung is enclosed within a pleural sac of two pleurae which allows the inner and outer walls to slide over each other whilst breathing takes place, without much friction. The inner visceral pleura divides each lung as fissures into sections called lobes. The right lung has three lobes and the left has two. The lobes are further divided into bronchopulmonary segments and lobules. The lungs have a unique blood supply, receiving deoxygenated blood sent from the heart to receive oxygen (the pulmonary circulation) and a separate supply of oxygenated blood (the bronchial circulation).

The tissue of the lungs can be affected by several respiratory diseases including pneumonia and lung cancer. Chronic diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and emphysema can be related to smoking or exposure to harmful substances. Diseases such as bronchitis can also affect the respiratory tract. Medical terms related to the lung often begin with pulmo-, from the Latin pulmonarius (of the lungs) as in pulmonology, or with pneumo- (from Greek πνεύμων "lung") as in pneumonia.

In embryonic development, the lungs begin to develop as an outpouching of the foregut, a tube which goes on to form the upper part of the digestive system. When the lungs are formed the fetus is held in the fluid-filled amniotic sac and so they do not function to breathe. Blood is also diverted from the lungs through the ductus arteriosus. At birth however, air begins to pass through the lungs, and the diversionary duct closes so that the lungs can begin to respire. The lungs only fully develop in early childhood.

Structure

[edit]Anatomy

[edit]

In humans, the lungs are located in the chest on either side of the heart in the rib cage. They are conical in shape with a narrow rounded apex at the top, and a broad concave base that rests on the convex surface of the diaphragm.[1] The apex of the lung extends into the root of the neck, reaching shortly above the level of the sternal end of the first rib. The lungs stretch from close to the backbone in the rib cage to the front of the chest and downwards from the lower part of the trachea to the diaphragm.[1]

The left lung shares space with the heart, and has an indentation in its border called the cardiac notch of the left lung to accommodate this.[2][3] The front and outer sides of the lungs face the ribs, which make light indentations on their surfaces. The medial surfaces of the lungs face towards the centre of the chest, and lie against the heart, great vessels, and the carina where the trachea divides into the two main bronchi.[3] The cardiac impression is an indentation formed on the surfaces of the lungs where they rest against the heart.

Both lungs have a central recession called the hilum, where the blood vessels and airways pass into the lungs making up the root of the lung.[4] There are also bronchopulmonary lymph nodes on the hilum.[3]

The lungs are surrounded by the pulmonary pleurae. The pleurae are two serous membranes; the outer parietal pleura lines the inner wall of the rib cage and the inner visceral pleura directly lines the surface of the lungs. Between the pleurae is a potential space called the pleural cavity containing a thin layer of lubricating pleural fluid.

Lobes

[edit]| Right lung | Left lung |

|---|---|

Upper

Middle

Lower

|

Upper

Lingula

Lower

|

Each lung is divided into sections called lobes by the infoldings of the visceral pleura as fissures. Lobes are divided into segments, and segments have further divisions as lobules. There are three lobes in the right lung and two lobes in the left lung.

Fissures

[edit]The fissures are formed in early prenatal development by invaginations of the visceral pleura that divide the lobar bronchi, and section the lungs into lobes that helps in their expansion.[6][7] The right lung is divided into three lobes by a horizontal fissure, and an oblique fissure. The left lung is divided into two lobes by an oblique fissure which is closely aligned with the oblique fissure in the right lung. In the right lung the upper horizontal fissure, separates the upper (superior) lobe from the middle lobe. The lower, oblique fissure separates the lower lobe from the middle and upper lobes.[1][7]

Variations in the fissures are fairly common being either incompletely formed or present as an extra fissure as in the azygos fissure, or absent. Incomplete fissures are responsible for interlobar collateral ventilation, airflow between lobes which is unwanted in some lung volume reduction procedures.[6]

Segments

[edit]The primary bronchi enter the lungs at the hilum and initially branch into secondary bronchi also known as lobar bronchi that supply air to each lobe of the lung. The lobar bronchi branch into tertiary bronchi also known as segmental bronchi and these supply air to the further divisions of the lobes known as bronchopulmonary segments. Each bronchopulmonary segment has its own (segmental) bronchus and arterial supply.[8] Segments for the left and right lung are shown in the table.[5] The segmental anatomy is useful clinically for localising disease processes in the lungs.[5] A segment is a discrete unit that can be surgically removed without seriously affecting surrounding tissue.[9]

Right lung

[edit]The right lung has both more lobes and segments than the left. It is divided into three lobes, an upper, middle, and a lower lobe by two fissures, one oblique and one horizontal.[10] The upper, horizontal fissure, separates the upper from the middle lobe. It begins in the lower oblique fissure near the posterior border of the lung, and, running horizontally forward, cuts the anterior border on a level with the sternal end of the fourth costal cartilage; on the mediastinal surface it may be traced back to the hilum.[1] The lower, oblique fissure, separates the lower from the middle and upper lobes and is closely aligned with the oblique fissure in the left lung.[1][7]

The mediastinal surface of the right lung is indented by a number of nearby structures. The heart sits in an impression called the cardiac impression. Above the hilum of the lung is an arched groove for the azygos vein, and above this is a wide groove for the superior vena cava and right brachiocephalic vein; behind this, and close to the top of the lung is a groove for the brachiocephalic artery. There is a groove for the oesophagus behind the hilum and the pulmonary ligament, and near the lower part of the oesophageal groove is a deeper groove for the inferior vena cava before it enters the heart.[3]

The weight of the right lung varies between individuals, with a standard reference range in men of 155–720 g (0.342–1.587 lb)[11] and in women of 100–590 g (0.22–1.30 lb).[12]

Left lung

[edit]The left lung is divided into two lobes, an upper and a lower lobe, by the oblique fissure, which extends from the costal to the mediastinal surface of the lung both above and below the hilum.[1] The left lung, unlike the right, does not have a middle lobe, though it does have a homologous feature, a projection of the upper lobe termed the lingula. Its name means "little tongue". The lingula on the left lung serves as an anatomic parallel to the middle lobe on the right lung, with both areas being predisposed to similar infections and anatomic complications.[13][14] There are two bronchopulmonary segments of the lingula: superior and inferior.[1]

The mediastinal surface of the left lung has a large cardiac impression where the heart sits. This is deeper and larger than that on the right lung, at which level the heart projects to the left.[3]

On the same surface, immediately above the hilum, is a well-marked curved groove for the aortic arch, and a groove below it for the descending aorta. The left subclavian artery, a branch off the aortic arch, sits in a groove from the arch to near the apex of the lung. A shallower groove in front of the artery and near the edge of the lung, lodges the left brachiocephalic vein. The oesophagus may sit in a wider shallow impression at the base of the lung.[3]

By standard reference range, the weight of the left lung is 110–675 g (0.243–1.488 lb)[11] in men and 105–515 g (0.231–1.135 lb) in women.[12]

Illustrations

[edit]-

Chest CT (axial lung window)

-

Chest CT (coronal lung window)

-

Chest CT (axial lung window)

-

Chest CT (coronal lung window)

-

"Meet the lungs" from Khan Academy

-

Pulmonology video

-

3D anatomy of the lung lobes and fissures.

Microanatomy

[edit]

The lungs are part of the lower respiratory tract, and accommodate the bronchial airways when they branch from the trachea. The bronchial airways terminate in alveoli which make up the functional tissue (parenchyma) of the lung, and veins, arteries, nerves, and lymphatic vessels.[3][15] The trachea and bronchi have plexuses of lymph capillaries in their mucosa and submucosa. The smaller bronchi have a single layer of lymph capillaries, and they are absent in the alveoli.[16] The lungs are supplied with the largest lymphatic drainage system of any other organ in the body.[17] Each lung is surrounded by a serous membrane of visceral pleura, which has an underlying layer of loose connective tissue attached to the substance of the lung.[18]

Connective tissue

[edit]

The connective tissue of the lungs is made up of elastic and collagen fibres that are interspersed between the capillaries and the alveolar walls. Elastin is the key protein of the extracellular matrix and is the main component of the elastic fibres.[19] Elastin gives the necessary elasticity and resilience required for the persistent stretching involved in breathing, known as lung compliance. It is also responsible for the elastic recoil needed. Elastin is more concentrated in areas of high stress such as the openings of the alveoli, and alveolar junctions.[19] The connective tissue links all the alveoli to form the lung parenchyma which has a sponge-like appearance. The alveoli have interconnecting air passages in their walls known as the pores of Kohn.[20]

Respiratory epithelium

[edit]All of the lower respiratory tract including the trachea, bronchi, and bronchioles is lined with respiratory epithelium. This is a ciliated epithelium interspersed with goblet cells which produce mucin the main component of mucus, ciliated cells, basal cells, and in the terminal bronchioles–club cells with actions similar to basal cells, and macrophages. The epithelial cells, and the submucosal glands throughout the respiratory tract secrete airway surface liquid (ASL), the composition of which is tightly regulated and determines how well mucociliary clearance works.[21]

Pulmonary neuroendocrine cells are found throughout the respiratory epithelium including the alveolar epithelium,[22] though they only account for around 0.5 percent of the total epithelial population.[23] PNECs are innervated airway epithelial cells that are particularly focused at airway junction points.[23] These cells can produce serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine, as well as polypeptide products. Cytoplasmic processes from the pulmonary neuroendocrine cells extend into the airway lumen where they may sense the composition of inspired gas.[24]

Bronchial airways

[edit]In the bronchi there are incomplete tracheal rings of cartilage and smaller plates of cartilage that keep them open.[25]: 472 Bronchioles are too narrow to support cartilage and their walls are of smooth muscle, and this is largely absent in the narrower respiratory bronchioles which are mainly just of epithelium.[25]: 472 The absence of cartilage in the terminal bronchioles gives them an alternative name of membranous bronchioles.[26]

Respiratory zone

[edit]The conducting zone of the respiratory tract ends at the terminal bronchioles when they branch into the respiratory bronchioles. This marks the beginning of the terminal respiratory unit called the acinus which includes the respiratory bronchioles, the alveolar ducts, alveolar sacs, and alveoli.[27] An acinus measures up to 10 mm in diameter.[28] A primary pulmonary lobule is the part of the lung distal to the respiratory bronchiole.[29] Thus, it includes the alveolar ducts, sacs, and alveoli but not the respiratory bronchioles.[30]

The unit described as the secondary pulmonary lobule is the lobule most referred to as the pulmonary lobule or respiratory lobule.[25]: 489 [31] This lobule is a discrete unit that is the smallest component of the lung that can be seen without aid.[29] The secondary pulmonary lobule is likely to be made up of between 30 and 50 primary lobules.[30] The lobule is supplied by a terminal bronchiole that branches into respiratory bronchioles. The respiratory bronchioles supply the alveoli in each acinus and is accompanied by a pulmonary artery branch. Each lobule is enclosed by an interlobular septum. Each acinus is incompletely separated by an intralobular septum.[28]

The respiratory bronchiole gives rise to the alveolar ducts that lead to the alveolar sacs, which contain two or more alveoli.[20] The walls of the alveoli are extremely thin allowing a fast rate of diffusion. The alveoli have interconnecting small air passages in their walls known as the pores of Kohn.[20]

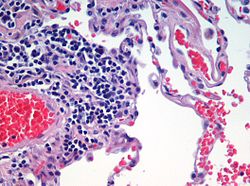

Alveoli

[edit]

Alveoli consist of two types of alveolar cell and an alveolar macrophage. The two types of cell are known as type I and type II cells[32] (also known as pneumocytes).[3] Types I and II make up the walls and alveolar septa. Type I cells provide 95% of the surface area of each alveoli and are flat ("squamous"), and Type II cells generally cluster in the corners of the alveoli and have a cuboidal shape.[33] Despite this, cells occur in a roughly equal ratio of 1:1 or 6:4.[32][33]

Type I are squamous epithelial cells that make up the alveolar wall structure. They have extremely thin walls that enable an easy gas exchange.[32] These type I cells also make up the alveolar septa which separate each alveolus. The septa consist of an epithelial lining and associated basement membranes.[33] Type I cells are not able to divide, and consequently rely on differentiation from Type II cells.[33]

Type II are larger and they line the alveoli and produce and secrete epithelial lining fluid, and lung surfactant.[34][32] Type II cells are able to divide and differentiate to Type I cells.[33]

The alveolar macrophages have an important role in the immune system. They remove substances which deposit in the alveoli including loose red blood cells that have been forced out from blood vessels.[33]

Microbiota

[edit]There is a large presence of microorganisms in the lungs known as the lung microbiota that interacts with the airway epithelial cells; an interaction of probable importance in maintaining homeostasis. The microbiota is complex and dynamic in healthy people, and altered in diseases such as asthma and COPD. For example significant changes can take place in COPD following infection with rhinovirus.[35] Fungal genera that are commonly found as mycobiota in the microbiota include Candida, Malassezia, Saccharomyces, and Aspergillus.[36][37]

Respiratory tract

[edit]

The lower respiratory tract is part of the respiratory system, and consists of the trachea and the structures below this including the lungs.[32] The trachea receives air from the pharynx and travels down to a place where it splits (the carina) into a right and left primary bronchus. These supply air to the right and left lungs, splitting progressively into the secondary and tertiary bronchi for the lobes of the lungs, and into smaller and smaller bronchioles until they become the respiratory bronchioles. These in turn supply air through alveolar ducts into the alveoli, where the exchange of gases take place.[32] Oxygen breathed in, diffuses through the walls of the alveoli into the enveloping capillaries and into the circulation,[20] and carbon dioxide diffuses from the blood into the lungs to be breathed out.

Estimates of the total surface area of lungs vary from 50 to 75 square metres (540 to 810 sq ft);[32][33] although this is often quoted in textbooks and the media being "the size of a tennis court",[33][38][39] it is actually less than half the size of a singles court.[40]

The bronchi in the conducting zone are reinforced with hyaline cartilage in order to hold open the airways. The bronchioles have no cartilage and are surrounded instead by smooth muscle.[33] Air is warmed to 37 °C (99 °F), humidified and cleansed by the conducting zone. Particles from the air being removed by the cilia on the respiratory epithelium lining the passageways,[41] in a process called mucociliary clearance.

Pulmonary stretch receptors in the smooth muscle of the airways initiate a reflex known as the Hering–Breuer reflex that prevents the lungs from over-inflation, during forceful inspiration.

Blood supply

[edit]

The lungs have a dual blood supply provided by a bronchial and a pulmonary circulation.[4] The bronchial circulation supplies oxygenated blood to the airways of the lungs, through the bronchial arteries that leave the aorta. There are usually three arteries, two to the left lung and one to the right, and they branch alongside the bronchi and bronchioles.[32] The pulmonary circulation carries deoxygenated blood from the heart to the lungs and returns the oxygenated blood to the heart to supply the rest of the body.[32]

The blood volume of the lungs is about 450 millilitres on average, about 9% of the total blood volume of the entire circulatory system. This quantity can easily fluctuate from between one-half and twice the normal volume. Also, in the event of blood loss through hemorrhage, blood from the lungs can partially compensate by automatically transferring to the systemic circulation.[42]

Nerve supply

[edit]The lungs are supplied by nerves of the autonomic nervous system. Input from the parasympathetic nervous system occurs via the vagus nerve.[4] When stimulated by acetylcholine, this causes constriction of the smooth muscle lining the bronchus and bronchioles, and increases the secretions from glands.[43][page needed] The lungs also have a sympathetic tone from norepinephrine acting on the beta 2 adrenoceptors in the respiratory tract, which causes bronchodilation.[44]

The action of breathing takes place because of nerve signals sent by the respiratory center in the brainstem, along the phrenic nerve from the cervical plexus to the diaphragm.[45]

Variation

[edit]The lobes of the lung are subject to anatomical variations.[46] A horizontal interlobar fissure was found to be incomplete in 25% of right lungs, or even absent in 11% of all cases. An accessory fissure was also found in 14% and 22% of left and right lungs, respectively.[47] An oblique fissure was found to be incomplete in 21% to 47% of left lungs.[48] In some cases a fissure is absent, or extra, resulting in a right lung with only two lobes, or a left lung with three lobes.[46]

A variation in the airway branching structure has been found specifically in the central airway branching. This variation is associated with the development of COPD in adulthood.[49]

Development

[edit]The development of the human lungs arise from the laryngotracheal groove and develop to maturity over several weeks in the foetus and for several years following birth.[50]

The larynx, trachea, bronchi and lungs that make up the respiratory tract, begin to form during the fourth week of embryogenesis[51] from the lung bud which appears ventrally to the caudal portion of the foregut.[52]

The respiratory tract has a branching structure, and is also known as the respiratory tree.[53] In the embryo this structure is developed in the process of branching morphogenesis,[54] and is generated by the repeated splitting of the tip of the branch. In the development of the lungs (as in some other organs) the epithelium forms branching tubes. The lung has a left-right symmetry and each bud known as a bronchial bud grows out as a tubular epithelium that becomes a bronchus. Each bronchus branches into bronchioles.[55] The branching is a result of the tip of each tube bifurcating.[53] The branching process forms the bronchi, bronchioles, and ultimately the alveoli.[53] The four genes mostly associated with branching morphogenesis in the lung are the intercellular signalling protein – sonic hedgehog (SHH), fibroblast growth factors FGF10 and FGFR2b, and bone morphogenetic protein BMP4. FGF10 is seen to have the most prominent role. FGF10 is a paracrine signalling molecule needed for epithelial branching, and SHH inhibits FGF10.[53][55] The development of the alveoli is influenced by a different mechanism whereby continued bifurcation is stopped and the distal tips become dilated to form the alveoli.

At the end of the fourth week, the lung bud divides into two, the right and left primary bronchial buds on each side of the trachea.[56][57] During the fifth week, the right bud branches into three secondary bronchial buds and the left branches into two secondary bronchial buds. These give rise to the lobes of the lungs, three on the right and two on the left. Over the following week, the secondary buds branch into tertiary buds, about ten on each side.[57] From the sixth week to the sixteenth week, the major elements of the lungs appear except the alveoli.[58] From week 16 to week 26, the bronchi enlarge and lung tissue becomes highly vascularised. Bronchioles and alveolar ducts also develop. By week 26, the terminal bronchioles have formed which branch into two respiratory bronchioles.[59] During the period covering the 26th week until birth the important blood–air barrier is established. Specialised type I alveolar cells where gas exchange will take place, together with the type II alveolar cells that secrete pulmonary surfactant, appear. The surfactant reduces the surface tension at the air-alveolar surface which allows expansion of the alveolar sacs. The alveolar sacs contain the primitive alveoli that form at the end of the alveolar ducts,[60] and their appearance around the seventh month marks the point at which limited respiration would be possible, and the premature baby could survive.[50]

Vitamin A deficiency

[edit]The developing lung is particularly vulnerable to changes in the levels of vitamin A. Vitamin A deficiency has been linked to changes in the epithelial lining of the lung and in the lung parenchyma. This can disrupt the normal physiology of the lung and predispose to respiratory diseases. Severe nutritional deficiency in vitamin A results in a reduction in the formation of the alveolar walls (septa) and to notable changes in the respiratory epithelium; alterations are noted in the extracellular matrix and in the protein content of the basement membrane. The extracellular matrix maintains lung elasticity; the basement membrane is associated with alveolar epithelium and is important in the blood-air barrier. The deficiency is associated with functional defects and disease states. Vitamin A is crucial in the development of the alveoli which continues for several years after birth.[61]

After birth

[edit]At birth, the baby's lungs are filled with fluid secreted by the lungs and are not inflated. After birth the infant's central nervous system reacts to the sudden change in temperature and environment. This triggers the first breath, within about ten seconds after delivery.[62] Before birth, the lungs are filled with fetal lung fluid.[63] After the first breath, the fluid is quickly absorbed into the body or exhaled. The resistance in the lung's blood vessels decreases giving an increased surface area for gas exchange, and the lungs begin to breathe spontaneously. This accompanies other changes which result in an increased amount of blood entering the lung tissues.[62]

At birth, the lungs are very undeveloped with only around one sixth of the alveoli of the adult lung present.[50] The alveoli continue to form into early adulthood, and their ability to form when necessary is seen in the regeneration of the lung.[64][65] Alveolar septa have a double capillary network instead of the single network of the developed lung. Only after the maturation of the capillary network can the lung enter a normal phase of growth. Following the early growth in numbers of alveoli there is another stage of the alveoli being enlarged.[66]

Function

[edit]Gas exchange

[edit]The major function of the lungs is gas exchange between the lungs and the blood.[67] The alveolar and pulmonary capillary gases equilibrate across the thin blood–air barrier.[34][68][69] This thin membrane (about 0.5 –2 μm thick) is folded into about 300 million alveoli, providing an extremely large surface area (estimates varying between 70 and 145 m2) for gas exchange to occur.[68][70]

The lungs are not capable of expanding to breathe on their own, and will only do so when there is an increase in the volume of the thoracic cavity.[71] This is achieved by the muscles of respiration, through the contraction of the diaphragm, and the intercostal muscles which pull the rib cage upwards as shown in the diagram.[72] During breathing out the muscles relax, returning the lungs to their resting position.[73] At this point the lungs contain the functional residual capacity (FRC) of air, which, in the adult human, has a volume of about 2.5–3.0 litres.[73]

During heavy breathing as in exertion, a large number of accessory muscles in the neck and abdomen are recruited, that during exhalation pull the ribcage down, decreasing the volume of the thoracic cavity.[73] The FRC is now decreased, but since the lungs cannot be emptied completely there is still about a litre of residual air left.[73] Lung function testing is carried out to evaluate lung volumes and capacities.

Protection

[edit]The lungs possess several characteristics which protect against infection. The respiratory tract is lined by respiratory epithelium or respiratory mucosa, with hair-like projections called cilia that beat rhythmically and carry mucus. This mucociliary clearance is an important defence system against air-borne infection.[34] The dust particles and bacteria in the inhaled air are caught in the mucosal surface of the airways, and are moved up towards the pharynx by the rhythmic upward beating action of the cilia.[33][74]: 661–730

The lining of the lung also secretes immunoglobulin A which protects against respiratory infections;[74] goblet cells secrete mucus[33] which also contains several antimicrobial compounds such as defensins, antiproteases, and antioxidants.[74] The size of the respiratory tract and the flow of air also protect the lungs from larger particles. Smaller particles deposit in the mouth and behind the mouth in the oropharynx, and larger particles are trapped in nasal hair after inhalation.[74]

Other

[edit]In addition to their function in respiration, the lungs have a number of other functions. They are involved in maintaining homeostasis, helping in the regulation of blood pressure as part of the renin–angiotensin system. The inner lining of the blood vessels secretes angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) an enzyme that catalyses the conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II.[75] The lungs are involved in the blood's acid–base homeostasis by expelling carbon dioxide when breathing.[71][76]

The lungs also serve a protective role. Several blood-borne substances, such as a few types of prostaglandins, leukotrienes, serotonin and bradykinin, are excreted through the lungs.[75] Drugs and other substances can be absorbed, modified or excreted in the lungs.[71][77] The lungs filter out small blood clots from veins and prevent them from entering arteries and causing strokes.[76]

The lungs also play a pivotal role in speech by providing air and airflow for the creation of vocal sounds,[71][78] and other paralanguage communications such as sighs and gasps.

Research suggests a role of the lungs in the production of blood platelets.[79]

Gene and protein expression

[edit]About 20,000 protein coding genes are expressed in human cells and almost 75% of these genes are expressed in the normal lung.[80][81] A little less than 200 of these genes are more specifically expressed in the lung with less than 20 genes being highly lung specific. The highest expression of lung specific proteins are different surfactant proteins,[34] such as SFTPA1, SFTPB and SFTPC, and napsin, expressed in type II pneumocytes. Other proteins with elevated expression in the lung are the dynein protein DNAH5 in ciliated cells, and the secreted SCGB1A1 protein in mucus-secreting goblet cells of the airway mucosa.[82]

Clinical significance

[edit]Lungs can be affected by a number of diseases and disorders. Pulmonology is the medical speciality that deals with respiratory diseases involving the lungs and respiratory system.[83] Cardiothoracic surgery deals with surgery of the lungs including lung volume reduction surgery, lobectomy, pneumectomy and lung transplantation.[84]

Inflammation and infection

[edit]Inflammatory conditions of the lung tissue are pneumonia, of the respiratory tract are bronchitis and bronchiolitis, and of the pleurae surrounding the lungs pleurisy. Inflammation is usually caused by infections due to bacteria or viruses. When the lung tissue is inflamed due to other causes it is called pneumonitis. One major cause of bacterial pneumonia is tuberculosis.[74] Chronic infections often occur in those with immunodeficiency and can include a fungal infection by Aspergillus fumigatus that can lead to an aspergilloma forming in the lung.[74][85] In the US certain species of rat can transmit a hantavirus to humans that can cause untreatable hantavirus pulmonary syndrome with a similar presentation to that of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).[86]

Alcohol affects the lungs and can cause inflammatory alcoholic lung disease. Acute exposure to alcohol stimulates the beating of cilia in the respiratory epithelium. However, chronic exposure has the effect of desensitising the ciliary response which reduces mucociliary clearance (MCC). MCC is an innate defense system protecting against pollutants and pathogens, and when this is disrupted the numbers of alveolar macrophages are decreased. A subsequent inflammatory response is the release of cytokines. Another consequence is the susceptibility to infection.[87][88]

Blood-supply changes

[edit]

A pulmonary embolism is a blood clot that becomes lodged in the pulmonary arteries. The majority of emboli arise because of deep vein thrombosis in the legs. Pulmonary emboli may be investigated using a ventilation/perfusion scan, a CT scan of the arteries of the lung, or blood tests such as the D-dimer.[74] Pulmonary hypertension describes an increased pressure at the beginning of the pulmonary artery that has a large number of differing causes.[74] Other rarer conditions may also affect the blood supply of the lung, such as granulomatosis with polyangiitis, which causes inflammation of the small blood vessels of the lungs and kidneys.[74]

A lung contusion is a bruise caused by chest trauma. It results in hemorrhage of the alveoli causing a build-up of fluid which can impair breathing, and this can be either mild or severe. The function of the lungs can also be affected by compression from fluid in the pleural cavity pleural effusion, or other substances such as air (pneumothorax), blood (hemothorax), or rarer causes. These may be investigated using a chest X-ray or CT scan, and may require the insertion of a surgical drain until the underlying cause is identified and treated.[74]

Obstructive lung diseases

[edit]

Asthma, bronchiectasis, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) that includes chronic bronchitis, and emphysema, are all obstructive lung diseases characterised by airway obstruction. This limits the amount of air that is able to enter alveoli because of constriction of the bronchial tree, due to inflammation. Obstructive lung diseases are often identified because of symptoms and diagnosed with pulmonary function tests such as spirometry.

Many obstructive lung diseases are managed by avoiding triggers (such as dust mites or smoking), with symptom control such as bronchodilators, and with suppression of inflammation (such as through corticosteroids) in severe cases. A common cause of chronic bronchitis, and emphysema, is smoking; and common causes of bronchiectasis include severe infections and cystic fibrosis. The definitive cause of asthma is not yet known, but it has been linked to other atopic diseases.[74][89]

The breakdown of alveolar tissue, often as a result of tobacco-smoking leads to emphysema, which can become severe enough to develop into COPD. Elastase breaks down the elastin in the lung's connective tissue that can also result in emphysema. Elastase is inhibited by the acute-phase protein, alpha-1 antitrypsin, and when there is a deficiency in this, emphysema can develop. With persistent stress from smoking, the airway basal cells become disarranged and lose their regenerative ability needed to repair the epithelial barrier. The disorganised basal cells are seen to be responsible for the major airway changes that are characteristic of COPD, and with continued stress can undergo a malignant transformation. Studies have shown that the initial development of emphysema is centred on the early changes in the airway epithelium of the small airways.[90] Basal cells become further deranged in a smoker's transition to clinically defined COPD.[90]

Restrictive lung diseases

[edit]Some types of chronic lung diseases are classified as restrictive lung disease, because of a restriction in the amount of lung tissue involved in respiration. These include pulmonary fibrosis which can occur when the lung is inflamed for a long period of time. Fibrosis in the lung replaces functioning lung tissue with fibrous connective tissue. This can be due to a large variety of occupational lung diseases such as Coalworker's pneumoconiosis, autoimmune diseases or more rarely to a reaction to medication.[74] Severe respiratory disorders, where spontaneous breathing is not enough to maintain life, may need the use of mechanical ventilation to ensure an adequate supply of air.

Cancers

[edit]Lung cancer can either arise directly from lung tissue or as a result of metastasis from another part of the body. There are two main types of primary tumour described as either small-cell or non-small-cell lung carcinomas. The major risk factor for cancer is smoking. Once a cancer is identified it is staged using scans such as a CT scan and a sample of tissue from a biopsy is taken. Cancers may be treated surgically by removing the tumour, the use of radiotherapy, chemotherapy or a combination, or with the aim of symptom control.[74] Lung cancer screening is being recommended in the United States for high-risk populations.[91]

Congenital disorders

[edit]Congenital disorders include cystic fibrosis, pulmonary hypoplasia (an incomplete development of the lungs)[92]congenital diaphragmatic hernia, and infant respiratory distress syndrome caused by a deficiency in lung surfactant. An azygos lobe is a congenital anatomical variation which though usually without effect can cause problems in thoracoscopic procedures.[93]

Pleural space pressure

[edit]A pneumothorax (collapsed lung) is an abnormal collection of air in the pleural space that causes an uncoupling of the lung from the chest wall.[94] The lung cannot expand against the air pressure inside the pleural space. An easy to understand example is a traumatic pneumothorax, where air enters the pleural space from outside the body, as occurs with puncture to the chest wall. Similarly, scuba divers ascending while holding their breath with their lungs fully inflated can cause air sacs (alveoli) to burst and leak high pressure air into the pleural space.

Examination

[edit]As part of a physical examination in response to respiratory symptoms of shortness of breath, and cough, a lung examination may be carried out. This exam includes palpation and auscultation.[95] The areas of the lungs that can be listened to using a stethoscope are called the lung fields, and these are the posterior, lateral, and anterior lung fields. The posterior fields can be listened to from the back and include: the lower lobes (taking up three quarters of the posterior fields); the anterior fields taking up the other quarter; and the lateral fields under the axillae, the left axilla for the lingual, the right axilla for the middle right lobe. The anterior fields can also be auscultated from the front.[96] An area known as the triangle of auscultation is an area of thinner musculature on the back which allows improved listening.[97] Abnormal breathing sounds heard during a lung exam can indicate the presence of a lung condition; wheezing for example is commonly associated with asthma and COPD.

Function testing

[edit]Lung function testing is carried out by evaluating a person's capacity to inhale and exhale in different circumstances.[98] The volume of air inhaled and exhaled by a person at rest is the tidal volume (normally 500–750 mL); the inspiratory reserve volume and expiratory reserve volume are the additional amounts a person is able to forcibly inhale and exhale respectively. The summed total of forced inspiration and expiration is a person's vital capacity. Not all air is expelled from the lungs even after a forced breath out; the remainder of the air is called the residual volume. Together these terms are referred to as lung volumes.[98]

Pulmonary plethysmographs are used to measure functional residual capacity.[99] Functional residual capacity cannot be measured by tests that rely on breathing out, as a person is only able to breathe a maximum of 80% of their total functional capacity.[100] The total lung capacity depends on the person's age, height, weight, and sex, and normally ranges between four and six litres.[98] Females tend to have a 20–25% lower capacity than males. Tall people tend to have a larger total lung capacity than shorter people. Smokers have a lower capacity than nonsmokers. Thinner persons tend to have a larger capacity. Lung capacity can be increased by physical training as much as 40% but the effect may be modified by exposure to air pollution.[100][101]

Other lung function tests include spirometry, measuring the amount (volume) and flow of air that can be inhaled and exhaled. The maximum volume of breath that can be exhaled is called the vital capacity. In particular, how much a person is able to exhale in one second (called forced expiratory volume (FEV1)) as a proportion of how much they are able to exhale in total (FEV). This ratio, the FEV1/FEV ratio, is important to distinguish whether a lung disease is restrictive or obstructive.[74][98] Another test is that of the lung's diffusing capacity – this is a measure of the transfer of gas from air to the blood in the lung capillaries.

Culinary uses

[edit]

Mammal lung is one of the main types of offal, or pluck, alongside the heart and trachea, and is consumed as a foodstuff around the world in dishes such as Scottish haggis. The United States Food and Drug Administration legally prohibits the sale of animal lungs due to concerns such as fungal spores or cross-contamination with other organs, although this has been criticised as unfounded.[102]

Other animals

[edit]Birds

[edit]

The lungs of birds are relatively small, but are connected to eight or nine air sacs that extend through much of the body, and are in turn connected to air spaces within the bones. On inhalation, air travels through the trachea of a bird into the air sacs. Air then travels continuously from the air sacs at the back, through the lungs, which are relatively fixed in size, to the air sacs at the front. From here, the air is exhaled. These fixed size lungs are called "circulatory lungs", as distinct from the "bellows-type lungs" found in most other animals.[103][105]

The lungs of birds contain millions of tiny parallel passages called parabronchi. Small sacs called atria radiate from the walls of the tiny passages; these, like the alveoli in other lungs, are the site of gas exchange by simple diffusion.[105] The blood flow around the parabronchi and their atria forms a cross-current process of gas exchange (see diagram on the right).[103][104]

The air sacs, which hold air, do not contribute much to gas exchange, despite being thin-walled, as they are poorly vascularised. The air sacs expand and contract due to changes in the volume in the thorax and abdomen. This volume change is caused by the movement of the sternum and ribs and this movement is often synchronised with movement of the flight muscles.[106]

Parabronchi in which the air flow is unidirectional are called paleopulmonic parabronchi and are found in all birds. Some birds, however, have, in addition, a lung structure where the air flow in the parabronchi is bidirectional. These are termed neopulmonic parabronchi.[105]

Reptiles

[edit]The lungs of most reptiles have a single bronchus running down the centre, from which numerous branches reach out to individual pockets throughout the lungs. These pockets are similar to alveoli in mammals, but much larger and fewer in number. These give the lung a sponge-like texture. In tuataras, snakes, and some lizards, the lungs are simpler in structure, similar to that of typical amphibians.[106]

Snakes and limbless lizards typically possess only the right lung as a major respiratory organ; the left lung is greatly reduced, or even absent. Amphisbaenians, however, have the opposite arrangement, with a major left lung, and a reduced or absent right lung.[106]

Both crocodilians and monitor lizards have lungs similar to those of birds, providing a unidirectional airflow and even possessing air sacs.[107] The now extinct pterosaurs have seemingly even further refined this type of lung, extending the airsacs into the wing membranes and, in the case of lonchodectids, Tupuxuara, and azhdarchoids, the hindlimbs.[108]

Reptilian lungs typically receive air via expansion and contraction of the ribs driven by axial muscles and buccal pumping. Crocodilians also rely on the hepatic piston method, in which the liver is pulled back by a muscle anchored to the pubic bone (part of the pelvis) called the diaphragmaticus,[109] which in turn creates negative pressure in the crocodile's thoracic cavity, allowing air to be moved into the lungs by Boyle's law. Turtles, which are unable to move their ribs, instead use their forelimbs and pectoral girdle to force air in and out of the lungs.[106]

Amphibians

[edit]

The lungs of most frogs and other amphibians are simple and balloon-like, with gas exchange limited to the outer surface of the lung. This is not very efficient, but amphibians have low metabolic demands and can also quickly dispose of carbon dioxide by diffusion across their skin in water, and supplement their oxygen supply by the same method. Amphibians employ a positive pressure system to get air to their lungs, forcing air down into the lungs by buccal pumping. This is distinct from most higher vertebrates, who use a breathing system driven by negative pressure where the lungs are inflated by expanding the rib cage.[110] In buccal pumping, the floor of the mouth is lowered, filling the mouth cavity with air. The throat muscles then presses the throat against the underside of the skull, forcing the air into the lungs.[111]

Due to the possibility of respiration across the skin combined with small size, all known lungless tetrapods are amphibians. The majority of salamander species are lungless salamanders, which respirate through their skin and tissues lining their mouth. This necessarily restricts their size: all are small and rather thread-like in appearance, maximising skin surface relative to body volume.[112] Other known lungless tetrapods are the Bornean flat-headed frog[113] and Atretochoana eiselti, a caecilian.[114]

The lungs of amphibians typically have a few narrow internal walls (septa) of soft tissue around the outer walls, increasing the respiratory surface area and giving the lung a honeycomb appearance. In some salamanders, even these are lacking, and the lung has a smooth wall. In caecilians, as in snakes, only the right lung attains any size or development.[106]

Fish

[edit]Lungs are found in three groups of fish; the coelacanths, the bichirs and the lungfish. Like in tetrapods, but unlike fish with swim bladder, the opening is at the ventral side of the oesophagus. The coelacanth has a nonfunctional and unpaired vestigial lung surrounded by a fatty organ.[115] Bichirs, the only group of ray-finned fish with lungs, have a pair which are hollow unchambered sacs, where the gas-exchange occurs on very flat folds that increase their inner surface area. The lungs of lungfish show more resemblance to tetrapod lungs. There is an elaborate network of parenchymal septa, dividing them into numerous respiration chambers.[116][117] In the Australian lungfish, there is only a single lung, albeit divided into two lobes. Other lungfish, however, have traditionally been considered having two lungs, but newer research defines paired lungs as bilateral lung buds that arise simultaneously and are both connected directly to the foregut, which is only seen in tetrapods.[118] In all lungfish, including the Australian, the lungs are located in the upper dorsal part of the body, with the connecting duct curving around and above the oesophagus. The blood supply also twists around the oesophagus, suggesting that the lungs originally evolved in the ventral part of the body, as in other vertebrates.[106]

Invertebrates

[edit]

A number of invertebrates have lung-like structures that serve a similar respiratory purpose to true vertebrate lungs, but are not evolutionarily related and only arise out of convergent evolution. Some arachnids, such as spiders and scorpions, have structures called book lungs used for atmospheric gas exchange. Some species of spider have four pairs of book lungs but most have two pairs.[119] Scorpions have spiracles on their body for the entrance of air to the book lungs.[120]

The coconut crab is terrestrial and uses structures called branchiostegal lungs to breathe air.[121] Juveniles are released into the ocean, however adults cannot swim and possess an only rudimentary set of gills. The adult crabs can breathe on land and hold their breath underwater.[122] The branchiostegal lungs are seen as a developmental adaptive stage from water-living to enable land-living, or from fish to amphibian.[123]

Pulmonates are mostly land snails and slugs that have developed a simple lung from the mantle cavity. An externally located opening called the pneumostome allows air to be taken into the mantle cavity lung.[124][125]

Evolutionary origins

[edit]The lungs of today's terrestrial vertebrates and the gas bladders of today's fish are believed to have evolved from simple sacs, as outpocketings of the oesophagus, that allowed early fish to gulp air under oxygen-poor conditions.[126] These outpocketings first arose in the bony fish. In most of the ray-finned fish, the sacs evolved into closed off gas bladders, while a number of carp, trout, herring, catfish, and eels have retained the physostome condition with the sac being open to the oesophagus. In more basal bony fish, such as the gar, bichir, bowfin and the lobe-finned fish, the sacs have evolved to primarily function as lungs.[126] The lobe-finned fish gave rise to the land-based tetrapods. Thus, the lungs of vertebrates are homologous to the gas bladders of fish (but not to their gills).[127]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Drake RL, Vogl W, Mitchell AW (2014). Gray's anatomy for students (3rd ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. pp. 167–174. ISBN 978-0-7020-5131-9.

- ^ Betts JG (2013). Anatomy & physiology. OpenStax College, Rice University. pp. 787–846. ISBN 978-1-938168-13-0. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Standring S (2008). Borley NR (ed.). Gray's Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice (40th ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. pp. 992–1000. ISBN 978-0-443-06684-9. Alt URL

- ^ a b c Moore K (2018). Clinically oriented anatomy (8th ed.). Wolters Kluwer. pp. 333–339. ISBN 978-1-4963-4721-3.

- ^ a b c Arakawa H, Niimi H, Kurihara Y, et al. (December 2000). "Expiratory high-resolution CT: diagnostic value in diffuse lung diseases". American Journal of Roentgenology. 175 (6): 1537–1543. doi:10.2214/ajr.175.6.1751537. PMID 11090370.

- ^ a b Koster TD, Slebos DJ (2016). "The fissure: interlobar collateral ventilation and implications for endoscopic therapy in emphysema". International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. 11: 765–73. doi:10.2147/COPD.S103807. PMC 4835138. PMID 27110109.

- ^ a b c Hacking C, Knipe H (22 March 2013). "Lung fissures". Radiopaedia. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ^ Jones J (May 2011). "Bronchopulmonary segmental anatomy | Radiology Reference Article | Radiopaedia.org". radiopaedia.org.

- ^ Tortora G (1987). Principles of anatomy and physiology (5th ed.). New York: Harper and Row. p. 564. ISBN 978-0-06-350729-6.

- ^ Chaudhry R, Bordoni B (January 2019). "Anatomy, Thorax, Lungs". StatPearls [Internet]. PMID 29262068.

- ^ a b Molina DK, DiMaio VJ (December 2012). "Normal Organ Weights in Men". The American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology. 33 (4): 368–372. doi:10.1097/PAF.0b013e31823d29ad. PMID 22182984. S2CID 32174574.

- ^ a b Molina DK, DiMaio VJ (September 2015). "Normal Organ Weights in Women". The American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology. 36 (3): 182–187. doi:10.1097/PAF.0000000000000175. PMID 26108038. S2CID 25319215.

- ^ Yu J, Pomerantz M, Bishop A, et al. (2011). "Lady Windermere revisited: Treatment with thoracoscopic lobectomy/segmentectomy for right middle lobe and lingular bronchiectasis associated with non-tuberculous mycobacterial disease". European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery. 40 (3): 671–675. doi:10.1016/j.ejcts.2010.12.028. PMID 21324708.

- ^ Ayed A (2004). "Resection of the right middle lobe and lingula in children for middle lobe/lingula syndrome". Chest. 125 (1): 38–42. doi:10.1378/chest.125.1.38. PMID 14718418. S2CID 45666843.

- ^ Young B, Lowe JS, Stevens A, et al. (2006). Wheater's functional histology: a text and colour atlas. Deakin PJ (illust) (5th ed.). [Edinburgh?]: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. pp. 234–250. ISBN 978-0-443-06850-8.

- ^ "The Lymphatic System – Human Anatomy". Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- ^ Saladin KS (2011). Human anatomy (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 634. ISBN 978-0-07-122207-5.

- ^ Dorland (9 June 2011). Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary (32nd ed.). Elsevier. p. 1077. ISBN 978-1-4160-6257-8. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- ^ a b Mithieux SM, Weiss AS (2005). "Elastin". Fibrous Proteins: Coiled-Coils, Collagen and Elastomers. Advances in Protein Chemistry. Vol. 70. pp. 437–461. doi:10.1016/S0065-3233(05)70013-9. ISBN 978-0-12-034270-9. PMID 15837523.

- ^ a b c d Pocock G, Richards CD (2006). Human physiology: the basis of medicine (3rd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 315–318. ISBN 978-0-19-856878-0.

- ^ Stanke F (2015). "The Contribution of the Airway Epithelial Cell to Host Defense". Mediators Inflamm. 2015 463016. doi:10.1155/2015/463016. PMC 4491388. PMID 26185361.

- ^ Van Lommel A (June 2001). "Pulmonary neuroendocrine cells (PNEC) and neuroepithelial bodies (NEB): chemoreceptors and regulators of lung development". Paediatric Respiratory Reviews. 2 (2): 171–6. doi:10.1053/prrv.2000.0126. PMID 12531066.

- ^ a b Garg A, Sui P, Verheyden JM, et al. (2019). "Consider the lung as a sensory organ: A tip from pulmonary neuroendocrine cells". Organ Development. Current Topics in Developmental Biology. Vol. 132. pp. 67–89. doi:10.1016/bs.ctdb.2018.12.002. ISBN 978-0-12-810489-7. PMID 30797518. S2CID 73489416.

- ^ Weinberger S, Cockrill B, Mandel J (2019). Principles of pulmonary medicine (Seventh ed.). Elsevier. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-323-52371-4.

- ^ a b c Hall J (2011). Guyton and Hall textbook of medical physiology (12th ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-4160-4574-8.

- ^ Abbott GF, Rosado-de-Christenson ML, Rossi SE, et al. (November 2009). "Imaging of Small Airways Disease". Journal of Thoracic Imaging. 24 (4): 285–298. doi:10.1097/RTI.0b013e3181c1ab83. PMID 19935225. S2CID 10249069.

- ^ Weinberger S (2019). Principles of Pulmonary Medicine. Elsevier. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-323-52371-4.

- ^ a b Hochhegger B (June 2019). "Pulmonary Acinus: Understanding the Computed Tomography Findings from an Acinar Perspective". Lung. 197 (3): 259–265. doi:10.1007/s00408-019-00214-7. hdl:10923/17852. PMID 30900014. S2CID 84846517.

- ^ a b Gray H, Standring S, Anhand N, eds. (2021). Gray's Anatomy: the anatomical basis of clinical practice (42nd ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier. p. 1028. ISBN 978-0-7020-7705-0.

- ^ a b Goel A (28 February 2010). "Primary pulmonary lobule". Retrieved 12 July 2019.

- ^ Gilcrease-Garcia B, Gaillard F (27 February 2010). "Secondary pulmonary lobule". radiopaedia.org. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Stanton, Bruce M., Koeppen, Bruce A., eds. (2008). Berne & Levy physiology (6th ed.). Philadelphia: Mosby/Elsevier. pp. 418–422. ISBN 978-0-323-04582-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Pawlina W (2015). Histology a Text & Atlas (7th ed.). Wolters Kluwer Health. pp. 670–678. ISBN 978-1-4511-8742-7.

- ^ a b c d Srikanth L, Venkatesh K, Sunitha MM, et al. (16 October 2015). "In vitro generation of type-II pneumocytes can be initiated in human CD34+ stem cells". Biotechnology Letters. 38 (2): 237–242. doi:10.1007/s10529-015-1974-2. PMID 26475269. S2CID 17083137.

- ^ Hiemstra PS, McCray PB J, Bals R (April 2015). "The innate immune function of airway epithelial cells in inflammatory lung disease". The European Respiratory Journal. 45 (4): 1150–62. doi:10.1183/09031936.00141514. PMC 4719567. PMID 25700381.

- ^ Cui L, Morris A, Ghedin E (2013). "The human mycobiome in health and disease". Genome Med. 5 (7): 63. doi:10.1186/gm467. PMC 3978422. PMID 23899327.

- ^ Richardson M, Bowyer P, Sabino R (1 April 2019). "The human lung and Aspergillus: You are what you breathe in?". Medical Mycology. 57 (Supplement_2): S145 – S154. doi:10.1093/mmy/myy149. PMC 6394755. PMID 30816978.

- ^ Miller J (11 April 2008). "Tennis Courts and Godzilla: A Conversation with Lung Biologist Thiennu Vu". UCSF News & Media. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- ^ "8 Interesting Facts About Lungs". Bronchiectasis News Today. 17 October 2016. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- ^ Notter, Robert H. (2000). Lung surfactants: basic science and clinical applications. New York: Marcel Dekker. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-8247-0401-8. Retrieved 11 October 2008.

- ^ Jiyuan Tu, Kiao Inthavong, Goodarz Ahmadi (2013). Computational fluid and particle dynamics in the human respiratory system (1st ed.). Dordrecht: Springer. pp. 23–24. ISBN 978-94-007-4487-5.

- ^ Guyton A, Hall J (2011). Medical Physiology. Saunders/Elsevier. p. 478. ISBN 978-1-4160-4574-8.

- ^ Levitzky MG (2013). "Chapter 2. Mechanics of Breathing". Pulmonary physiology (8th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. ISBN 978-0-07-179313-1.

- ^ Johnson M (January 2006). "Molecular mechanisms of beta(2)-adrenergic receptor function, response, and regulation". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 117 (1): 18–24, quiz 25. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2005.11.012. PMID 16387578.

- ^ Tortora G, Derrickson B (2011). Principles of Anatomy & Physiology. Wiley. p. 504. ISBN 978-0-470-64608-3.

- ^ a b Moore K (2018). Clinically oriented anatomy (8th ed.). Wolters Kluwer. p. 342. ISBN 978-1-4963-4721-3.

- ^ "Variations in the lobes and fissures of lungs – a study in South Indian lung specimens". European Journal of Anatomy. 18 (1): 16–20. 9 June 2019. ISSN 1136-4890.

- ^ Meenakshi S, Manjunath KY, Balasubramanyam V (2004). "Morphological variations of the lung fissures and lobes". The Indian Journal of Chest Diseases & Allied Sciences. 46 (3): 179–82. PMID 15553206.

- ^ Marko Z (2018). "Human lung development:recent progress and new challenges". Development. 145 (16) dev163485. doi:10.1242/dev.163485. PMC 6124546. PMID 30111617.

- ^ a b c Sadler T (2010). Langman's medical embryology (11th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 204–207. ISBN 978-0-7817-9069-7.

- ^ Moore, K.L., Persaud, T.V.N. (2002). The Developing Human: Clinically Oriented Embryology (7th ed.). Saunders. ISBN 978-0-7216-9412-2.

- ^ Hill M. "Respiratory System Development". UNSW Embryology. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ a b c d Miura T (2008). "Modeling Lung Branching Morphogenesis". Multiscale Modeling of Developmental Systems. Current Topics in Developmental Biology. Vol. 81. pp. 291–310. doi:10.1016/S0070-2153(07)81010-6. ISBN 978-0-12-374253-7. PMID 18023732.

- ^ Ochoa-Espinosa A, Affolter M (1 October 2012). "Branching morphogenesis: from cells to organs and back". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 4 (10) a008243. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a008243. PMC 3475165. PMID 22798543.

- ^ a b Wolpert L (2015). Principles of development (5th ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 499–500. ISBN 978-0-19-967814-3.

- ^ Sadler T (2010). Langman's medical embryology (11th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 202–204. ISBN 978-0-7817-9069-7.

- ^ a b Larsen WJ (2001). Human embryology (3. ed.). Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone. p. 144. ISBN 978-0-443-06583-5.

- ^ Kyung Won, Chung (2005). Gross Anatomy (Board Review). Hagerstown, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 156. ISBN 978-0-7817-5309-8.

- ^ Larsen WJ (2001). Human embryology (3. ed.). Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-443-06583-5.

- ^ Alberts D (2012). Dorland's illustrated medical dictionary (32nd ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier. p. 56. ISBN 978-1-4160-6257-8.

- ^ Timoneda J, Rodríguez-Fernández L, Zaragozá R, et al. (21 August 2018). "Vitamin A Deficiency and the Lung". Nutrients. 10 (9): 1132. doi:10.3390/nu10091132. PMC 6164133. PMID 30134568.

- ^ a b "Changes in the newborn at birth". MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia.

- ^ O'Brodovich H (2001). "Fetal lung liquid secretion". American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology. 25 (1): 8–10. doi:10.1165/ajrcmb.25.1.f211. PMID 11472968.

- ^ Schittny JC, Mund SI, Stampanoni M (February 2008). "Evidence and structural mechanism for late lung alveolarization". American Journal of Physiology. Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology. 294 (2): L246–254. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.420.7315. doi:10.1152/ajplung.00296.2007. PMID 18032698.

- ^ Schittny JC (March 2017). "Development of the lung". Cell and Tissue Research. 367 (3): 427–444. doi:10.1007/s00441-016-2545-0. PMC 5320013. PMID 28144783.

- ^ Burri PH (1984). "Fetal and postnatal development of the lung". Annual Review of Physiology. 46: 617–628. doi:10.1146/annurev.ph.46.030184.003153. PMID 6370120.

- ^ Tortora G, Anagnostakos N (1987). Principles of Anatomy and Physiology. Harper and Row. p. 555. ISBN 978-0-06-350729-6.

- ^ a b Williams PL, Warwick R, Dyson M, et al. (1989). Gray's Anatomy (37th ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. pp. 1278–1282. ISBN 0443-041776.

- ^ "Gas Exchange in humans". Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- ^ Tortora G, Anagnostakos N (1987). Principles of Anatomy and Physiology. Harper and Row. p. 574. ISBN 978-0-06-350729-6.

- ^ a b c d Levitzky MG (2013). "Chapter 1. Function and Structure of the Respiratory System". Pulmonary physiology (8th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. ISBN 978-0-07-179313-1.

- ^ Tortora GJ, Anagnostakos NP (1987). Principles of anatomy and physiology (Fifth ed.). New York: Harper & Row, Publishers. p. 567. ISBN 978-0-06-350729-6.

- ^ a b c d Tortora GJ, Anagnostakos NP (1987). Principles of anatomy and physiology (Fifth ed.). New York: Harper & Row, Publishers. pp. 556–582. ISBN 978-0-06-350729-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Brian R. Walker, Nicki R. Colledge, Stuart H. Ralston, Ian D. Penman, eds. (2014). Davidson's principles and practice of medicine. Illustrations by Robert Britton (22nd ed.). Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-7020-5035-0.

- ^ a b Walter F. Boron (2004). Medical Physiology: A Cellular And Molecular Approach. Elsevier/Saunders. p. 605. ISBN 978-1-4160-2328-9.

- ^ a b Hoad-Robson R, Kenny T. "The Lungs and Respiratory Tract". Patient.info. Patient UK. Archived from the original on 15 September 2015. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- ^ Smyth HD (2011). "Chapter 2". Controlled pulmonary drug delivery. New York: Springer. ISBN 978-1-4419-9744-9.

- ^ Mannell R. "Introduction to Speech Production". Macquarie University. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ^ "An overlooked role for lungs in blood formation". National Institutes of Health (NIH). 3 April 2017. Archived from the original on 4 April 2017.

- ^ "The human proteome in lung – The Human Protein Atlas". www.proteinatlas.org. Retrieved 25 September 2017.

- ^ Uhlén M, Fagerberg L, Hallström BM, et al. (23 January 2015). "Tissue-based map of the human proteome". Science. 347 (6220) 1260419. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.665.2415. doi:10.1126/science.1260419. PMID 25613900. S2CID 802377.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - ^ Lindskog C, Fagerberg L, Hallström B, et al. (28 August 2014). "The lung-specific proteome defined by integration of transcriptomics and antibody-based profiling". The FASEB Journal. 28 (12): 5184–5196. doi:10.1096/fj.14-254862. PMID 25169055.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - ^ American College of Physicians. "Pulmonology". ACP. Archived from the original on 9 September 2015. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ "The Surgical Specialties: 8 – Cardiothoracic Surgery". Royal College of Surgeons. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ "Aspergilloma". Medical Dictionary. TheFreeDictionary.

- ^ "Clinical Manifestation | Hantavirus | DHCPP | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 21 February 2019. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

- ^ Arvers P (December 2018). "[Alcohol consumption and lung damage: Dangerous relationships]". Revue des maladies respiratoires. 35 (10): 1039–1049. doi:10.1016/j.rmr.2018.02.009. PMID 29941207. S2CID 239523761.

- ^ Slovinsky WS, Romero F, Sales D, et al. (November 2019). "The involvement of GM-CSF deficiencies in parallel pathways of pulmonary alveolar proteinosis and the alcoholic lung". Alcohol (Fayetteville, N.Y.). 80: 73–79. doi:10.1016/j.alcohol.2018.07.006. PMC 6592783. PMID 31229291.

- ^ Galli E, Gianni S, Auricchio G, et al. (1 September 2007). "Atopic dermatitis and asthma". Allergy and Asthma Proceedings. 28 (5): 540–543. doi:10.2500/aap2007.28.3048. ISSN 1088-5412. PMID 18034972.

- ^ a b Crystal RG (15 December 2014). "Airway basal cells. The "smoking gun" of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 190 (12): 1355–62. doi:10.1164/rccm.201408-1492PP. PMC 4299651. PMID 25354273.

- ^ "Lung Cancer Screening". U.S. Preventative Services Task Force. 2013. Archived from the original on 4 November 2010. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- ^ Cadichon SB (2007), "Chapter 22: Pulmonary hypoplasia", in Kumar P, Burton BK (eds.), Congenital malformations: evidence-based evaluation and management

- ^ Sieunarine K, May J, White G, et al. (August 1997). "Anomalous azygos vein: a potential danger during endoscopic thoracic sypathectomy". ANZ Journal of Surgery. 67 (8): 578–579. doi:10.1111/j.1445-2197.1997.tb02046.x. PMID 9287933.

- ^ Bintcliffe O, Maskell N (8 May 2014). "Spontaneous pneumothorax" (PDF). BMJ. 348 g2928. doi:10.1136/bmj.g2928. PMID 24812003. S2CID 32575512. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ Weinberger S, Cockrill B, Mandell J (2019). Principles of Pulmonary Pathology. Elsevier. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-323-52371-4.

- ^ "Lung examination". meded.ucsd.edu. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- ^ Malik N, Tedder BL, Zemaitis MR (January 2021). Anatomy, Thorax, Triangle of Auscultation. PMID 30969656.

- ^ a b c d Kim E B (2012). "Chapter 34. Introduction to Pulmonary Structure and Mechanics". Ganong's review of medical physiology (24th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. ISBN 978-0-07-178003-2.

- ^ Criée C, Sorichter S, Smith H, et al. (July 2011). "Body plethysmography – Its principles and clinical use". Respiratory Medicine. 105 (7): 959–971. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2011.02.006. PMID 21356587.

- ^ a b Applegate E (2014). The Anatomy and Physiology Learning System. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 335. ISBN 978-0-323-29082-1.

- ^ Laeremans M (2018). "Black Carbon Reduces the Beneficial Effect of Physical Activity on Lung Function". Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 50 (9): 1875–1881. doi:10.1249/MSS.0000000000001632. hdl:10044/1/63478. PMID 29634643. S2CID 207183760.

- ^ Davies, Madeline. "Here's Why It's Illegal to Sell Animal Lungs for Consumption in the U.S.", Eater, 10 November 2021. Retrieved 26 January 2023.

- ^ a b c Ritchson G. "BIO 554/754 – Ornithology: Avian respiration". Department of Biological Sciences, Eastern Kentucky University. Retrieved 23 April 2009.

- ^ a b Scott GR (2011). "Commentary: Elevated performance: the unique physiology of birds that fly at high altitudes". Journal of Experimental Biology. 214 (15): 2455–2462. doi:10.1242/jeb.052548. PMID 21753038.

- ^ a b c Maina JN (2005). The lung air sac system of birds development, structure, and function; with 6 tables. Berlin: Springer. pp. 3.2–3.3 "Lung", "Airway (Bronchiol) System" 66–82. ISBN 978-3-540-25595-6.

- ^ a b c d e f Romer AS, Parsons TS (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 330–334. ISBN 978-0-03-910284-5.

- ^ "Unidirectional airflow in the lungs of birds, crocs…and now monitor lizards!?". Sauropod Vertebra picture of the week. 11 December 2013. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ Claessens LP, O'Connor PM, Unwin DM, et al. (18 February 2009). "Respiratory Evolution Facilitated the Origin of Pterosaur Flight and Aerial Gigantism". PLOS ONE. 4 (2) e4497. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.4497C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0004497. PMC 2637988. PMID 19223979.

- ^ Munns SL, Owerkowicz T, Andrewartha SJ, et al. (1 March 2012). "The accessory role of the diaphragmaticus muscle in lung ventilation in the estuarine crocodile Crocodylus porosus". The Journal of Experimental Biology. 215 (Pt 5): 845–852. Bibcode:2012JExpB.215..845M. doi:10.1242/jeb.061952. PMID 22323207.

- ^ Janis CM, Keller JC (2001). "Modes of ventilation in early tetrapods: Costal aspiration as a key feature of amniotes". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 46 (2): 137–170.

- ^ Brainerd EL (December 1999). "New perspectives on the evolution of lung ventilation mechanisms in vertebrates". Experimental Biology Online. 4 (2): 1–28. Bibcode:1999EvBO....4b...1B. doi:10.1007/s00898-999-0002-1. S2CID 35368264.

- ^ Duellman W, Trueb L (1994). Biology of amphibians. illustrated by L. Trueb. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-4780-6.

- ^ Bickford D (15 April 2008). "First Lungless Frog Discovered in Indonesia". Scientific American.

- ^ Wilkinson M, Sebben A, Schwartz E, et al. (April 1998). "The largest lungless tetrapod: report on a second specimen of (Amphibia: Gymnophiona: Typhlonectidae) from Brazil". Journal of Natural History. 32 (4): 617–627. doi:10.1080/00222939800770321.

- ^ Lambertz M (2017). "The vestigial lung of the coelacanth and its implications for understanding pulmonary diversity among vertebrates: New perspectives and open questions". Royal Society Open Science. 4 (11). Bibcode:2017RSOS....471518L. doi:10.1098/rsos.171518. PMC 5717702. PMID 29291127.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Fish Physiology: From Genome to Environment. Academic Press. June 2011. ISBN 978-0-08-092323-9.

- ^ Zaccone G, Mauceri A, Maisano M, et al. (2007). "Innervation and Neurotransmitter Localization in the Lung of the Nile bichir Polypterus bichir bichir". The Anatomical Record. 290 (9): 1166–1177. doi:10.1002/ar.20576. PMID 17722050.

- ^ Camila Cupello, Tatsuya Hirasawa, Norifumi Tatsumi, Yoshitaka Yabumoto, Pierre Gueriau, Sumio Isogai, Ryoko Matsumoto, Toshiro Saruwatari, Andrew King, Masato Hoshino, Kentaro Uesugi, Masataka Okabe, Paulo M Brito (2022) Lung evolution in vertebrates and the water-to-land transition, eLife

- ^ "book lung | anatomy". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- ^ "spiracle | anatomy". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- ^ Farrelly CA, Greenaway P (2005). "The morphology and vasculature of the respiratory organs of terrestrial hermit crabs (Coenobita and Birgus): gills, branchiostegal lungs and abdominal lungs". Arthropod Structure & Development. 34 (1): 63–87. Bibcode:2005ArtSD..34...63F. doi:10.1016/j.asd.2004.11.002.

- ^ Burggren WW, McMahon BR (1988). Biology of the Land Crabs. Cambridge University Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-521-30690-4.

- ^ Burggren WW, McMahon BR (1988). Biology of the Land Crabs. Cambridge University Press. p. 331. ISBN 978-0-521-30690-4.

- ^ Land Snails (& other Air-Breathers in Pulmonata Subclass & Sorbeconcha Clade). at Washington State University Tri-Cities Natural History Museum. Accessed 25 February 2016. http://shells.tricity.wsu.edu/ArcherdShellCollection/Gastropoda/Pulmonates.html Archived 2018-11-09 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hochachka PW (2014). Mollusca: Metabolic Biochemistry and Molecular Biomechanics. Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-4832-7603-8.

- ^ a b Colleen Farmer (1997). "Did lungs and the intracardiac shunt evolve to oxygenate the heart in vertebrates" (PDF). Paleobiology. 23 (3): 358–372. Bibcode:1997Pbio...23..358F. doi:10.1017/S0094837300019734. S2CID 87285937. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 June 2010.

- ^ Longo S, Riccio M, McCune AR (June 2013). "Homology of lungs and gas bladders: Insights from arterial vasculature". Journal of Morphology. 274 (6): 687–703. Bibcode:2013JMorp.274..687L. doi:10.1002/jmor.20128. PMID 23378277. S2CID 29995935.