Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Radical mastectomy

View on Wikipedia| Radical mastectomy | |

|---|---|

Radical Mastectomy |

Radical mastectomy is a surgical procedure that treats breast cancer by removing the breast and its underlying chest muscle (including pectoralis major and pectoralis minor), and lymph nodes of the axilla (armpit). Breast cancer is the most common cancer among women. In the early twentieth century, it was primarily treated by surgery, which is when the mastectomy was developed.[1] However, with the advancement of technology and surgical skills in recent years, mastectomies have become less invasive.[2] As of 2016[update], a combination of radiotherapy and breast-conserving mastectomy are considered optimal treatment. From 1890 to 1971, these procedures were performed solely because it was believed they were the best option. William Halsted and other believers refused to hear any other proposal or perform any research to conclude his findings. This invasive procedure occurred due to the lack of control group to see if it was actually the radical mastectomy that was helping the cancer.

Radical mastectomy

[edit]

Halsted and Meyer were the first to achieve successful results with the radical mastectomy, thus ushering in the modern era of surgical treatment for breast cancer. In 1894, William Halsted published his work with radical mastectomy from the 50 cases operated at Johns Hopkins between 1889 and 1894.[3] Willy Meyer also published research on radical mastectomy from his interactions with New York patients in December 1894.[4] The en bloc removal of the breast tissue became known as the Halsted mastectomy before adopting the title "the complete operation" and eventually, "the radical mastectomy" as it is known today.[5]

Radical mastectomy was based on the medical belief at the time that breast cancer spread locally at first, invading nearby tissue and then spreading to surrounding lymph ducts where the cells were "trapped". It was thought that hematic spread of tumor cells occurred at a much later stage.[1] Halsted himself believed that cancer spread in a "centrifugal spiral", solidifying this opinion in the medical community at the time.[6]

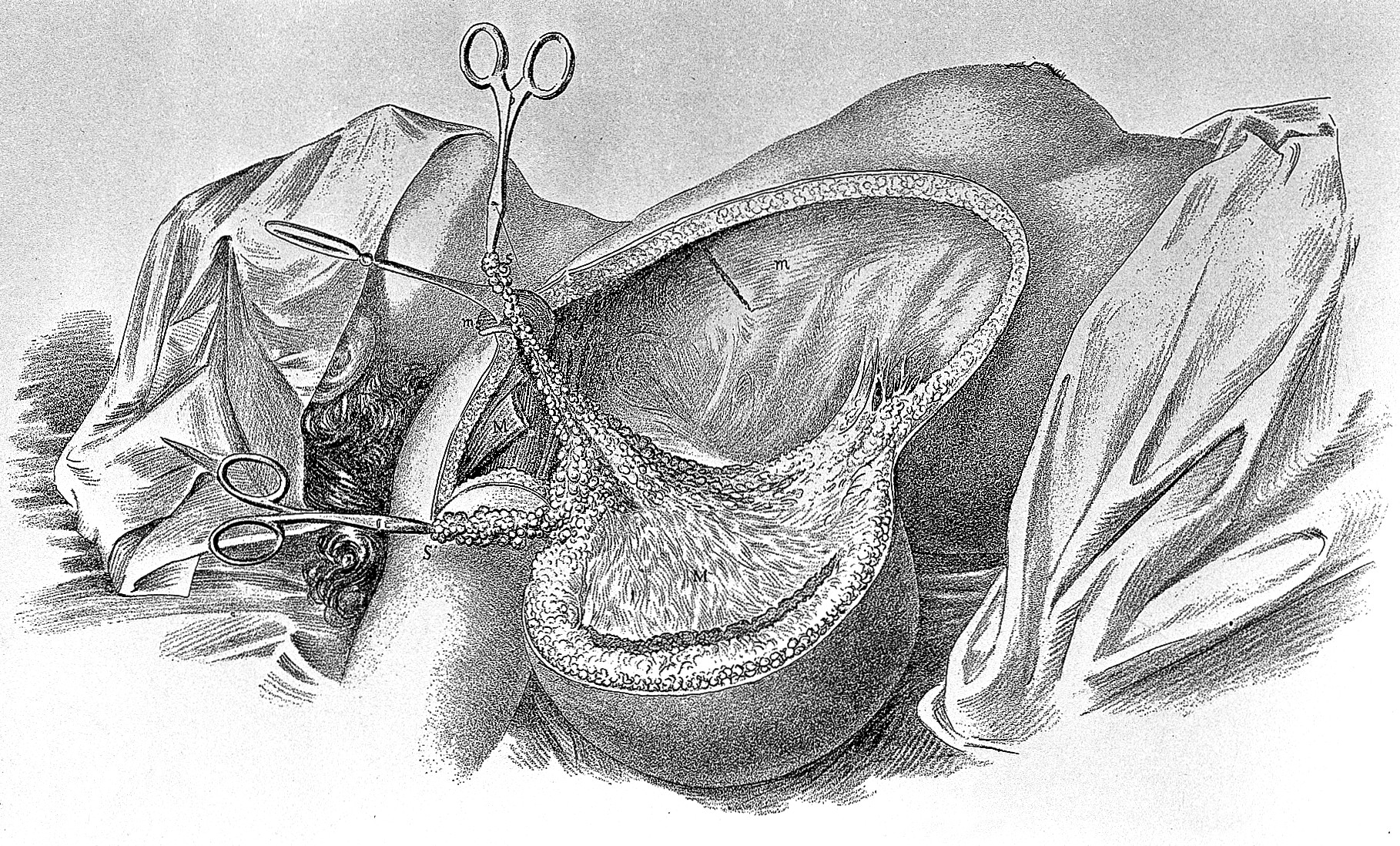

Radical mastectomy involves removing all the breast tissue, overlying skin, the pectoralis muscles, and all the axillary lymph nodes. Skin was removed because the disease involved the skin, which was often ulcerated.[3][7] The pectoralis muscles were removed not only because the chest wall was involved, but also because it was thought that removal of the transpectoral lymphatic pathways were necessary. It was also thought, at that time, that it was anatomically impossible to do a complete axillary dissection without removing the pectoralis muscle.[3][4]

William Halsted accomplished a three-year recurrence rate of 3% and a locoregional recurrence rate of 20% with no perioperative mortality. The five-year survival rate was 40%, which was twice that of untreated patients.[3] However, post-operation morbidity rates were high as the large wounds were left to heal by granulation, lymphedema was ubiquitous, and arm movement was highly restricted. Thus, chronic pain became a prevalent sequela. Because surgeons were faced with such large breast cancers that seemed to need drastic treatment methods, the quality of patient life was not taken into consideration.[7][8][9][10][11][12][13][excessive citations]

Nonetheless, due to Halsted and Meyer's work, it was possible to cure some cases of breast cancer and knowledge of the disease began to increase. Standardized treatments were created, and controlled long-term studies were conducted. Soon, it became apparent that some women with advanced stages of the disease did not benefit from surgery. In 1943, Haagensen and Stout reviewed over 500 patients who had radical mastectomy for breast cancer and identified a group of patients who could not be cured by radical mastectomy thus developing the concepts of operability and inoperability.[14] The signs of inoperability included ulceration of the skin, fixation to the chest wall, satellite nodules, edema of the skin (peau d'orange), supraclavicular lymph node enlargement, axillary lymph nodes greater than 2.5 cm, or matted, fixed lymph nodes.[14] This contribution of Haagensen and his colleagues would eventually lead to the development of a clinical staging system for breast cancer, the Columbia Clinical Classification, which is a landmark in the study of biology and treatment of breast cancer.[citation needed]

Today, surgeons rarely perform radical mastectomies, as a 1977 study by the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP), led by Bernard Fisher, showed that there was no statistical difference in survival or recurrence between radical mastectomies and less invasive surgeries.[15][16]

Extended radical mastectomies

[edit]According to the Halsted-Meyer theory, the major pathway for breast cancer dissemination was through the lymphatic ducts. Therefore, it was thought that performing wider and more mutilating surgeries that removed a greater number of lymph nodes would result in greater chances of cure.[17] From 1920 onwards, many surgeons performed surgeries more invasive than the original procedure by Halsted. Sampson Handley noted Halsted's observation of the existence of malignant metastasis to the chest wall and breast bone via the chain of internal mammary nodes under the sternum and employed an "extended" radical mastectomy that included the removal of the lymph nodes located there and the implantation of radium needles into the anterior intercostal spaces.[18] This line of study was extended by his son, Richard S. Handley, who studied internal mammary chain nodal involvement in breast cancer and demonstrated that 33% of 150 breast cancer patients had internal mammary chain involvement at the time of surgery.[19] The radical mastectomy was subsequently extended by a number of surgeons such as Sugarbaker and Urban to include removal of internal mammary lymph nodes.[20][21] Eventually, this "extended" radical mastectomy was extended even further to include removal of the supraclavicular lymph nodes at the time of mastectomy by Dahl-Iversen and Tobiassen.[22] Some surgeons like Prudente even went as far as amputating the upper arm en bloc with the mastectomy specimen in an attempt to cure relatively advanced local disease.[23] This increasingly radical progression culminated in the 'super-radical' mastectomy which consisted of complete excision of all breast tissue, axillary content, removal of the latissimus dorsi, pectoralis major and minor muscles and dissection of the internal mammary lymph nodes.[24] After retrospective analysis, the extended radical mastectomies were abandoned as these massive and disabling operations proved to be not superior to those of the standard radical mastectomies.[citation needed]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Zurrida, Stefano; Bassi, Fabio; Arnone, Paolo; Martella, Stefano; Castillo, Andres Del; Martini, Rafael Ribeiro; Semenkiw, M. Eugenia; Caldarella, Pietro (2011-06-05). "The Changing Face of Mastectomy (from Mutilation to Aid to Breast Reconstruction)". International Journal of Surgical Oncology. 2011 980158. doi:10.1155/2011/980158. ISSN 2090-1402. PMC 3263661. PMID 22312537.

- ^ Plesca M, Bordea C, El Houcheimi B, Ichim E, Blidaru A (2016). "Evolution of radical mastectomy for breast cancer". J Med Life. 9 (2): 183–6. ISSN 1844-3117. PMC 4863512. PMID 27453752.

- ^ a b c d Halsted, William S. (1894-11-01). "I. The Results of Operations for the Cure of Cancer of the Breast Performed at the Johns Hopkins Hospital from June, 1889, to January, 1894". Annals of Surgery. 20 (5): 497–555. doi:10.1097/00000658-189407000-00075. ISSN 0003-4932. PMC 1493925. PMID 17860107.

- ^ a b W. Meyer, "An improved method of the radical operation for carcinoma of the breast", New York Medical Record, vol. 46, pp. 746–749, 1894.

- ^ Sakorafas, G.h.; Safioleas, Michael (2010-01-01). "Breast cancer surgery: an historical narrative. Part II. 18th and 19th centuries". European Journal of Cancer Care. 19 (1): 6–29. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2354.2008.01060.x. ISSN 1365-2354. PMID 19674073.

- ^ Newmark, J.J. (2016). "No ordinary meeting': Robert McWhirter and the decline of radical mastectomy". The Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. 46 (1): 43–48. doi:10.4997/jrcpe.2016.110. PMID 27092369.

- ^ a b HALSTED, WILLIAM STEWART (1913-02-08). "Developments in the Skin-Grafting Operation for Cancer of the Breast". JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 60 (6): 416. doi:10.1001/jama.1913.04340060008004. ISSN 0002-9955.

- ^ Riddell, V. H. (2017-04-21). "The Technique of Radical Mastectomy: With Special Reference to the Management of the Skin Short Case and the Prevention of Functional Disability". British Journal of Cancer. 4 (3): 289–297. doi:10.1038/bjc.1950.27. ISSN 0007-0920. PMC 2007674. PMID 14783660.

- ^ Neumann, Charles G.; Conway, Herbert (1948-01-01). "Evaluation of skin grafting in the technique of radical mastectomy in relation to function of the arm". Surgery. 23 (3): 584–90. ISSN 0039-6060. PMID 18906044.

- ^ Bard, Morton (2017-04-21). "The sequence of emotional reactions in radical mastectomy patients". Public Health Reports. 67 (11): 1144–1148. doi:10.2307/4588308. ISSN 0094-6214. JSTOR 4588308. PMC 2030852. PMID 12993982.

- ^ Parker, Joe M.; Russo, P. E.; Oesterreicher, D. L. (1952). "Investigation of Cause of Lymphedema of the Upper Extremity After Radical Mastectomy". Radiology. 59 (4): 538–545. doi:10.1148/59.4.538. PMID 12983584.

- ^ JR, VON RONNEN (1955-01-01). "[Spontaneous rib fractures after radical mastectomy]". Journal Belge de Radiologie. 38 (4): 525–34. ISSN 0302-7430. PMID 13331884.

- ^ Fitts WT, Keuhnelian JG, Ravdin IS, Schor S (March 1954). "Swelling of the arm after radical mastectomy; a clinical study of its causes". Surgery. 35 (3): 460–64. PMID 13146467.

- ^ a b Townsend, Courtney; Abston, Sally; Fish, Jay (May 1985). "Surgical Adjuvant Treatment of Locally Advanced Breast Cancer". Ann Surg. 201 (5): 604–10. doi:10.1097/00000658-198505000-00009. PMC 1250769. PMID 3994434.

- ^ Fisher, B.; Montague, E.; Redmond, C.; Barton, B.; Borland, D.; Fisher, E. R.; Deutsch, M.; Schwarz, G.; Margolese, R. (June 1977). "Comparison of radical mastectomy with alternative treatments for primary breast cancer. A first report of results from a prospective randomized clinical trial". Cancer. 39 (6 Suppl): 2827–2839. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(197706)39:6<2827::aid-cncr2820390671>3.0.co;2-i. ISSN 0008-543X. PMID 326381.

- ^ Mukherjee, Siddhartha (2011). The Emperor of All Maladies. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. pp. 200–201. ISBN 978-1-4391-0795-9.

- ^ Carey, J.M.; Kirklin, J.W. (1952-10-01). "Extended radical mastectomy: a review of its concepts". Proceedings of the Staff Meetings of the Mayo Clinic. 27 (22): 436–40. ISSN 0092-699X. PMID 13004011.

- ^ Schachter, Karen; Neuhauser, Duncan (1981). Surgery for breast cancer. DIANE Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4289-2458-1.

- ^ Handley, R. S.; Thackray, A. C. (1954-01-09). "Invasion of Internal Mammary Lymph Nodes in Carcinoma of the Breast". British Medical Journal. 1 (4853): 61–63. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.4853.61. ISSN 0007-1447. PMC 2093179. PMID 13106471.

- ^ Sugarbaker, E. D. (1953-09-01). "Radical mastectomy combined with in-continuity resection of the homolateral internal mammary node chain". Cancer. 6 (5): 969–979. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(195309)6:5<969::aid-cncr2820060516>3.0.co;2-5. ISSN 0008-543X. PMID 13094645.

- ^ Urban, J. A. (1964-03-01). "Surgical excision of internal mammary nodes for breast cancer". The British Journal of Surgery. 51 (3): 209–212. doi:10.1002/bjs.1800510311. ISSN 0007-1323. PMID 14129436. S2CID 5680572.

- ^ Dahl-Iversen, E.; Tobiassen, T. (1969-12-01). "Radical mastectomy with parasternal and supraclavicular dissection for mammary carcinoma". Annals of Surgery. 170 (6): 889–891. doi:10.1097/00000658-196912000-00006. ISSN 0003-4932. PMC 1387715. PMID 5352643.

- ^ PACK, GEORGE T. (1961-11-01). "Interscapulomammothoracic Amputation for Malignant Melanoma". Archives of Surgery. 83 (5): 694–9. doi:10.1001/archsurg.1961.01300170050010. ISSN 0004-0010. PMID 14483062.

- ^ "Super Radical Mastectomy". TheFreeDictionary.com. Retrieved 2017-04-02.

Radical mastectomy

View on GrokipediaOverview

Definition

A radical mastectomy is a surgical procedure that entails the complete en bloc resection of the breast, including all breast tissue, the nipple-areolar complex, overlying skin, both the pectoralis major and pectoralis minor muscles, and the entire axillary lymph node basin, performed to minimize the risk of tumor cell dissemination during surgery.[5][3] This extensive removal was designed under the Halstedian theory, which posited that breast cancer originates locally and spreads centrifugally through contiguous tissues and lymphatic channels to regional lymph nodes before becoming systemic, thereby necessitating aggressive local-regional control for potential cure.[5][6] The procedure's original purpose was curative treatment of operable breast cancer, aiming to excise all potentially involved tissues in a single contiguous specimen to interrupt presumed orderly lymphatic progression and achieve long-term survival.[3] By targeting the chest wall muscles—specifically the pectoralis major and minor—radical mastectomy anatomically differs from less invasive approaches, as these structures are preserved in variants like the modified radical mastectomy to reduce morbidity while addressing similar oncologic goals.[2][7]Comparison to other mastectomy types

Radical mastectomy is distinguished by its extensive en bloc resection, which removes the entire breast tissue, overlying skin, nipple-areolar complex, axillary lymph nodes, and both pectoral muscles (major and minor) to disrupt potential routes of local tumor dissemination through lymphatic and muscular pathways.[2] This approach contrasts sharply with less invasive procedures, prioritizing comprehensive local control at the cost of greater functional morbidity, such as arm and shoulder impairment due to muscle sacrifice.[4] In comparison, a simple (total) mastectomy limits removal to all breast tissue, the nipple-areolar complex, and overlying skin, while preserving the underlying pectoral muscles and typically involving only sentinel lymph node evaluation rather than full axillary dissection.[2] This procedure avoids the muscular excision central to radical mastectomy, reducing postoperative disability and facilitating easier recovery, though it may not address extensive nodal or muscular involvement as aggressively.[8] The rationale for simple mastectomy emphasizes breast tissue clearance without compromising chest wall integrity, making it suitable when muscle invasion is absent.[4] The modified radical mastectomy serves as an intermediate option, combining total mastectomy with complete axillary lymph node dissection but sparing the pectoral muscles to minimize lymphedema and range-of-motion limitations compared to the radical variant.[2] Unlike radical mastectomy, which targets muscular involvement for presumed en bloc tumor containment, the modified approach relies on adjuvant therapies to manage systemic risks while preserving muscle function for better quality of life.[8] This evolution reflects a shift toward balancing oncologic efficacy with reduced morbidity, as studies have shown comparable survival outcomes without muscle removal.[4] Skin-sparing and nipple-sparing mastectomies further diverge from radical mastectomy by prioritizing aesthetic reconstruction; both remove all breast tissue and often axillary nodes but preserve the breast skin envelope—and in nipple-sparing cases, the nipple-areolar complex—for immediate implant or flap-based reconstruction.[2] These techniques are incompatible with radical mastectomy's muscle excision, which disrupts the chest wall and complicates reconstructive planning due to altered anatomy and higher complication rates.[8] Their rationale centers on oncologic safety through complete glandular removal while optimizing cosmetic and psychosocial outcomes, particularly for early-stage disease without skin or nipple involvement.[4] Partial mastectomy, also known as lumpectomy, represents the least extensive breast surgery, excising only the tumor and a margin of surrounding healthy tissue while conserving the majority of the breast, nipple-areolar complex, skin, muscles, and lymph nodes (with sentinel biopsy if needed).[2] This breast-conserving method starkly opposes radical mastectomy's total ablative intent, focusing instead on localized control supplemented by radiation therapy to achieve equivalent local recurrence rates without the profound tissue loss or functional deficits.[9] The underlying principle is to preserve form and function for small, favorable tumors, leveraging multimodal treatment to match the radical procedure's historical goal of cure.[4]| Mastectomy Type | Breast Tissue | Nipple-Areolar Complex | Skin | Axillary Lymph Nodes | Pectoral Muscles | Primary Rationale for Difference from Radical |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simple (Total) | All removed | Removed | Partial removal | Sentinel biopsy (limited) | Preserved | Avoids muscle/nodal excision for less morbidity when invasion absent[2] |

| Modified Radical | All removed | Removed | Partial removal | Full dissection | Preserved | Balances nodal clearance with muscle preservation for similar outcomes[8] |

| Skin-Sparing | All removed | Removed | Mostly preserved | Dissection if indicated (sentinel biopsy or full based on staging) | Preserved | Enables reconstruction by retaining skin envelope; lymph nodes managed separately[4] |

| Nipple-Sparing | All removed | Preserved | Mostly preserved | Dissection if indicated (sentinel biopsy or full based on staging) | Preserved | Optimizes aesthetics while ensuring glandular clearance; lymph nodes managed separately[2] |

| Partial (Lumpectomy) | Tumor + margin only | Preserved | Preserved | Sentinel biopsy (if indicated) | Preserved | Breast conservation with adjuvant radiation for localized disease[9] |

History

Development by William Halsted

William Stewart Halsted, a pioneering American surgeon at Johns Hopkins Hospital, developed the radical mastectomy as a comprehensive surgical approach to breast cancer in the late 19th century. He first performed the procedure in 1882 while at Roosevelt Hospital in New York, but refined and systematically applied it at Johns Hopkins starting in 1889, publishing his initial results in 1894 based on 50 cases treated between June 1889 and January 1894.[10][3] Halsted's innovation stemmed from his extensive training in Europe, where he observed advanced surgical techniques, and was influenced by contemporaries such as British surgeon William Mitchell Banks, who in 1882 advocated for routine axillary lymph node dissection alongside mastectomy, and German surgeon Ernst Küster, who promoted similar lymphatic clearance as early as 1871 to address cancer spread.[11][3] Halsted's modifications emphasized en bloc resection—removing the breast, underlying pectoral muscles, and axillary lymph nodes in a single specimen—to achieve maximal local control, building on but surpassing the partial excisions common in Europe at the time. This approach was grounded in his theory of the orderly centrifugal spread of breast cancer through the lymphatic system, positing that tumor cells progressed predictably from the primary site to regional nodes and beyond, necessitating wide excision to interrupt this pathway and prevent recurrence.[10][3] By prioritizing meticulous hemostasis, aseptic technique, and anatomical precision, Halsted aimed to minimize operative risks while maximizing tumor clearance, marking a shift toward radical surgery as the standard for operable breast cancer.[10] Early outcomes from Halsted's series demonstrated the procedure's efficacy in reducing local recurrence. In his 1894 report, only 6% of the 50 patients experienced recurrence in the operative field, a stark improvement over the 50-80% rates reported by European surgeons using less extensive methods. By 1907, Halsted had expanded his experience to 232 cases, maintaining a local recurrence rate of approximately 6%, with 5-year survival rates of 54% in operable cases, underscoring the technique's role in establishing local control and influencing surgical practice worldwide for decades.[12][10][12]Evolution and decline in use

Following the development of the original radical mastectomy, surgeons began exploring less invasive modifications to reduce morbidity while maintaining oncologic efficacy. In 1948, David Patey and William Dyson introduced the modified radical mastectomy, which preserved the pectoralis major muscle but removed the pectoralis minor, while still including complete axillary lymph node dissection, based on their analysis of over 1,000 cases showing comparable survival rates to the Halsted procedure with fewer complications.[13] This approach gained traction as it mitigated the severe functional impairments associated with muscle resection. In the 1960s, Hugh Auchincloss further adapted the technique by preserving both pectoral muscles entirely, arguing that routine removal was unnecessary for most cases and led to excessive disability without improving outcomes, as evidenced by his review of lymph node involvement patterns.[14] The use of radical mastectomy began to decline significantly in the post-1970s era, driven by accumulating evidence from randomized controlled trials demonstrating that less extensive surgery did not compromise survival. A pivotal study, the NSABP B-06 trial led by Bernard Fisher and colleagues in 1985, randomized patients with early-stage breast cancer to total mastectomy or segmental mastectomy (lumpectomy) with or without radiation, finding equivalent disease-free and overall survival rates at five years across arms, thus challenging the need for radical en bloc resection. Subsequent long-term follow-up confirmed these results, with no survival advantage for more aggressive surgery, accelerating the shift toward breast-conserving therapies.[15] By the 2020s, radical mastectomy has become exceedingly rare, comprising less than 1% of mastectomies performed in the United States, according to Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program data analyzing surgical trends from 2000 to 2020.[16] This decline stems from advances in preoperative imaging for earlier detection, effective adjuvant chemotherapy to control microscopic disease systemically, and the adoption of sentinel lymph node biopsy, which allows targeted axillary assessment without full dissection in most cases, thereby minimizing lymphedema and arm dysfunction.[17] These innovations have prioritized quality of life alongside oncologic control, rendering the procedure largely obsolete except in select advanced cases.Surgical Procedure

Standard technique

The standard technique for radical mastectomy, as originally described by William Halsted in 1894, is performed under general anesthesia to ensure patient comfort and immobility during the extensive dissection.[18] Preoperative marking typically outlines the incision, which extends from the midline of the sternum, curving around the breast to the posterior axillary line, allowing access to the breast, axilla, and chest wall structures.[19] This elliptical or teardrop-shaped incision facilitates the en bloc removal of tissues while preserving viable skin flaps for closure. The procedure begins with the incision through the skin and subcutaneous tissue, raising superior and inferior skin flaps to expose the breast parenchyma and underlying pectoralis major muscle. The entire breast, including the nipple-areola complex and all glandular tissue, is then mobilized and excised en bloc with the axillary contents. Axillary lymph node dissection encompasses levels I through III, involving careful removal of nodes from lateral to medial to the pectoralis minor muscle, along with surrounding fatty and lymphatic tissues, to achieve complete regional clearance without breaching the specimen.[18][20] Following breast and nodal excision, the pectoralis minor muscle is sequentially detached from its insertions and removed to expose level II and III nodes fully, after which the pectoralis major muscle is incised along its sternal and clavicular attachments and excised en bloc with the specimen, including any involved fascia or adjacent tissues such as portions of the serratus anterior if necessary. This step ensures wide margins around the tumor bed, reflecting Halsted's principle of eradicating local disease through comprehensive resection.[18][20] The dissection adheres strictly to en bloc principles to avoid tumor spillage, with hemostasis achieved through ligation and cautery. Closure involves approximating the raised skin flaps over the chest wall defect without underlying drains in the original Halsted method, relying on natural drainage and pressure dressings to manage serous fluid accumulation; skin grafting, such as Thiersch grafts, may be used for larger defects in the axilla or chest to facilitate healing.[18][20] In contemporary applications of this rarely performed procedure, adjuncts like sentinel lymph node evaluation may precede full axillary dissection if nodal status is uncertain, though the core en bloc muscle resection distinguishes it from less invasive variants like the modified radical mastectomy, while more invasive variants like the extended radical mastectomy incorporate internal mammary node removal.[21]Extended radical variant

The extended radical mastectomy represents an aggressive surgical modification of the standard radical mastectomy, incorporating the en bloc resection of the internal mammary lymph node chain alongside the removal of the breast, overlying skin, nipple-areolar complex, both pectoralis muscles, and axillary lymph nodes. Introduced by surgeon Jerome A. Urban in the early 1950s, this procedure was designed to achieve more comprehensive lymphatic clearance by targeting the internal mammary nodes, which lie along the internal mammary artery and vein in the parasternal region and serve as a key drainage pathway for medial and central breast tumors. Urban's technique emphasized continuity of resection to minimize the risk of disseminating tumor cells, performing the internal mammary dissection through an extension of the primary mastectomy incision rather than a separate parasternal approach, though the latter could be employed for enhanced exposure in select cases.[22][23] The rationale for this variant stemmed from pathological studies revealing internal mammary node involvement in approximately one-third of breast cancer cases, with rates exceeding 40% in medial quadrant tumors or when axillary nodes were positive, prompting the need for broader nodal excision to improve locoregional control and potentially survival in operable but advanced disease. In Urban's method, the dissection typically spans the first five intercostal spaces, with selective removal of costal cartilages (often the second through fifth) if tumor adherence or anatomical constraints necessitated it, ensuring en bloc excision while preserving pleural integrity where possible. This approach was particularly advocated for primary tumors in medial or central locations or those with clinical evidence of internal mammary involvement, as these sites correlated with higher metastatic risk to the chain.[24][25] Historically, the extended radical mastectomy gained traction in the mid-20th century as an evolution of Halsted's operation, applied in selected operable cases with suspected multicentric or nodal spread, but its use waned after randomized controlled trials in the 1960s and 1970s, such as the Princess Margaret Hospital study and others, demonstrated no overall survival benefit compared to standard radical mastectomy despite equivalent locoregional control. These trials, involving hundreds of patients with stage I and II disease, reported 5-year survival rates of 75-80% for both arms, with marginal trends favoring extended surgery only in medial tumor subgroups (e.g., 88% vs. 66% at 5 years, though not statistically significant). Today, the procedure is rarely indicated due to its obsolescence in favor of less invasive options like modified radical mastectomy combined with adjuvant therapies, driven by evidence of comparable outcomes with reduced surgical burden.[24] The extended variant carries elevated morbidity relative to standard radical mastectomy, primarily from the parasternal dissection and potential chest wall resection, including higher rates of arm lymphedema, shoulder immobility, and chronic pain, as well as cardiac toxicity risks from proximity to vital structures. Postoperative complications such as wound infections, seromas, and pleural effusions occur more frequently, with historical series noting up to 20-30% incidence of significant chest wall deformities due to cartilage removal and tissue deficit, often requiring reconstructive intervention. These factors, coupled with the lack of proven therapeutic gain, have relegated the procedure to historical significance in contemporary breast cancer management.[24][27]Indications and Contraindications

Current clinical indications

In contemporary clinical practice, radical mastectomy is infrequently performed due to advancements in neoadjuvant therapies and less invasive surgical options, but it remains indicated in select cases of locally advanced breast cancer (stage IIIA-IIIC) where there is confirmed invasion of the pectoral muscles or chest wall, or extensive axillary lymph node involvement that persists despite neoadjuvant systemic therapy. This approach ensures complete resection in scenarios where modified radical mastectomy would be insufficient to achieve clear margins.[28][29] Rarely, radical mastectomy may be considered for inflammatory breast cancer when deep muscle involvement is present, although modified radical mastectomy is the standard following neoadjuvant treatment in most operable cases. Similarly, in Paget's disease of the breast with underlying invasive carcinoma and pectoral muscle invasion, this procedure can be warranted to address extensive local disease, though such instances are uncommon given the preference for breast-conserving approaches or modified techniques when feasible.[30][31] As a salvage procedure, radical mastectomy is occasionally utilized for locoregional recurrence after prior breast-conserving surgery or modified mastectomy, particularly if the recurrence involves the chest wall or muscles; however, it is not recommended as first-line treatment per current guidelines, such as those from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) version 2025, which prioritize multimodal therapy with systemic agents and radiation.[32]00593-0/abstract)Contraindications and patient selection

Radical mastectomy is contraindicated in patients with stage IV metastatic breast cancer, as systemic therapy is the primary approach and surgery does not improve survival in such cases.[33] It is also absolutely contraindicated in individuals with poor performance status, such as an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) score greater than 2, who cannot tolerate the extensive general anesthesia and operative duration required.[33] Additionally, patient refusal of the procedure due to its high morbidity constitutes an absolute contraindication, emphasizing the need for thorough informed consent.[2] Relative contraindications include significant comorbidities that elevate perioperative risks, such as severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), which can impair chest wall healing and respiratory function post-muscle resection.[2] Patient preferences for immediate breast reconstruction may also render radical mastectomy relatively unsuitable, as removal of the pectoralis major and minor muscles disrupts flap-based reconstructive options that rely on preserved musculature.[34] Patient selection for radical mastectomy, now rarely performed in less than 5% of breast cancer surgical cases as of 2024, involves a multidisciplinary team review to ensure suitability for advanced local disease where modified approaches are infeasible.[35] Preoperative imaging with MRI or PET-CT is essential to confirm absence of distant metastases, aligning with current indications for locoregionally advanced tumors. Informed consent must detail the trade-offs between potential local control benefits and substantial functional morbidity, particularly in patients without contraindications to less invasive alternatives.[2]Complications and Risks

Immediate and short-term complications

Radical mastectomy, involving extensive removal of the breast, underlying pectoral muscles, and axillary lymph nodes, carries a higher risk of immediate and short-term complications compared to less invasive procedures due to the broad dissection required. Intraoperative hemorrhage occurs in up to 5% of cases, often necessitating meticulous hemostasis techniques to control bleeding from the large operative field; in about 2% of patients, significant bleeding requires return to the operating room within 24 hours.[2] Nerve injuries are common during axillary clearance, with the long thoracic nerve at particular risk, leading to winged scapula in up to 10% of patients; injury to the intercostobrachial nerve frequently causes sensory loss and numbness in the upper arm and axilla.[36][37] Postoperatively, within the first 30 days, wound infections develop in 5-8% of patients, typically presenting as superficial surgical site infections treatable with antibiotics, though deeper infections may require drainage and prolonged hospitalization. Seroma and hematoma formation is prevalent due to disruption of lymphatic and vascular structures, affecting up to 15-20% significantly enough to warrant aspiration or surgical evacuation; seromas occur in nearly all cases to some degree but are managed conservatively in most. Flap necrosis, resulting from compromised blood supply to the skin flaps amid extensive muscle resection, is rare in radical mastectomy and may necessitate debridement if full-thickness.[2][38][39] Patients typically require a hospital stay of 1 night for monitoring, though historical data for this procedure suggest longer durations of 5-7 days in the absence of modern enhanced recovery protocols. Pain management relies on multimodal analgesia, including opioids for moderate to severe postoperative pain from chest wall and axillary dissection, supplemented by non-opioids to minimize side effects. Early mobilization, initiated within 24-48 hours alongside mechanical prophylaxis like compression devices, is standard to prevent deep vein thrombosis (DVT), which has a low incidence of 0.2-1% in breast surgery patients under these measures.[2][40][41]Long-term complications

Radical mastectomy is associated with a high incidence of lymphedema due to the comprehensive axillary lymph node dissection, with rates reported at 22.3% in patients not receiving radiotherapy and rising to 44.4% in those who do (based on historical data from 1972–1995).[42] These figures exceed those observed in modified radical mastectomy, where lymphedema occurs in 19.1% without radiotherapy and 28.9% with it.[42] The condition arises from disrupted lymphatic drainage, leading to persistent arm swelling that can impair daily activities and quality of life. Shoulder dysfunction is another prevalent long-term issue, with approximately 50% of patients experiencing reduced range of motion, often due to the excision of the pectoralis major and minor muscles combined with postoperative scarring and fibrosis.[43] This limitation typically affects flexion, abduction, and external rotation, contributing to ongoing functional deficits in upper limb mobility. Cosmetically, the removal of the breast tissue and chest wall muscles results in significant chest wall deformity, creating a flattened or concave appearance that alters the thoracic contour.[44] Patients frequently report phantom breast sensations or pain, with non-painful sensations persisting in 19% and pain in about 1% two years postoperatively.[45] Psychologically, these changes exacerbate body image disturbances, including dissatisfaction with appearance, perceived loss of femininity, and reluctance to engage socially or intimately.[46] Breast reconstruction following radical mastectomy presents unique challenges owing to the absence of pectoral muscles, which complicates submuscular implant placement and often necessitates alternative techniques such as prepectoral implants or autologous flaps.[47] Additional long-term complications include chronic pain syndrome, affecting 20% to 68% of patients as a neuropathic condition involving the chest wall, axilla, or arm.[48] Breast cancer treatments in general contribute to bone density loss, compounding risks in survivors.Prognosis and Outcomes

Survival and recurrence rates

In Halsted's original series from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, radical mastectomy yielded 5-year survival rates of approximately 40% for patients with operable breast cancer, representing a substantial advancement over contemporary nonsurgical options.[49] Early reports varied slightly, with some cohorts achieving up to 50% survival depending on patient selection and tumor characteristics.[50] Due to the infrequency of radical mastectomy in modern practice, contemporary data on outcomes remain limited, with most evidence derived from historical series or small cohorts. In such cases, primarily for locally advanced stage III breast cancer often following neoadjuvant chemotherapy, recent studies report 5-year overall survival rates of 70-80% when combined with postmastectomy radiation and systemic therapies.[51] For instance, a cohort treated between 2005 and 2013 achieved an 83.4% 5-year overall survival rate for stage II-III disease, with stage III subsets showing outcomes in the 70-76% range after accounting for nodal involvement.[51] Radical mastectomy provides excellent local control, with 5-year loco-regional recurrence rates below 10% (equating to >90% control) in historical and select modern series.[6] Despite this, disease recurrence and mortality are predominantly driven by distant metastases rather than local failure.[52] Comparative randomized trials from the 1980s, such as the Milan trial, demonstrated no overall survival advantage for radical mastectomy over less invasive techniques like quadrantectomy plus axillary dissection and radiation, with 8-year survival rates of 83% versus 85%.[53] Similarly, a prospective trial comparing radical to modified radical mastectomy reported comparable 5-year survival (84% versus 76%, p>0.05) and local recurrence rates.[54] Key prognostic factors influencing survival include tumor stage, with more advanced nodal involvement correlating to poorer outcomes.[51] Estrogen receptor-positive status significantly improves disease-free survival in node-positive cases when hormonal adjuvant therapy (e.g., tamoxifen) is administered post-surgery.[55] The integration of adjuvant chemotherapy and endocrine therapies has further optimized results, yielding survival rates equivalent to those from modified radical mastectomy or breast-conserving approaches in equivalent-risk patients.[55]Functional and quality-of-life impacts

Radical mastectomy, by excising the pectoralis major and minor muscles along with the breast tissue and axillary lymph nodes, often results in substantial loss of upper extremity strength due to muscular atrophy and nerve disruption. Data specific to radical mastectomy is limited due to its rarity; studies on modified radical mastectomy (which preserves the pectoralis major) report reductions of 20-40% in affected arm function, suggesting potentially greater impairment with radical procedure.[56] This impairment can limit daily activities such as lifting or reaching, necessitating comprehensive rehabilitation. Physical therapy, focusing on range of motion, strengthening exercises, and scar management, is typically initiated within days to weeks post-surgery and may extend for 3-6 months or longer to restore function, with patients often requiring 10-15 supervised sessions followed by home-based programs.[57] Aesthetically, the procedure leaves a pronounced chest wall deformity characterized by a flattened contour and visible scarring, particularly without immediate reconstruction, which can profoundly affect body image. Implant-based reconstruction faces unique challenges in radical mastectomy cases due to the absence of pectoral muscle support, increasing risks of implant displacement, poor projection, and higher complication rates compared to procedures preserving muscular integrity. Autologous tissue reconstruction, such as using latissimus dorsi flaps, may offer better contour restoration but involves additional surgical morbidity.[58] Psychologically, patients undergoing radical mastectomy experience elevated rates of depression, with prevalence around 25-28% in the first year post-surgery, exceeding those observed in breast-conserving approaches due to altered body image and perceived loss of femininity; this is inferred from studies on modified radical mastectomy. Anxiety and stress levels are similarly heightened, contributing to diminished psychosocial well-being. Long-term studies indicate worse quality-of-life scores in domains like body image and treatment satisfaction for mastectomy compared to lumpectomy, with effect sizes showing significantly lower psychosocial and sexual well-being at 10 years.[59][60][61] Mitigation strategies emphasize multidisciplinary care, including psychological interventions like cognitive behavioral therapy and counseling, which reduce negative emotions and enhance resilience, alongside prosthetic devices for aesthetic restoration. Such supports can improve emotional outcomes and overall quality of life, though persistent functional limitations like lymphedema may exacerbate arm impairments in up to 20-30% of cases.[62][63]Modern Alternatives

Modified radical mastectomy

The modified radical mastectomy (MRM) is a surgical procedure that removes the entire breast, including the nipple-areolar complex and overlying skin, along with the axillary lymph nodes, while preserving the pectoralis major muscle (and the pectoralis minor in modern variants).[34] This muscle-sparing approach was introduced in 1948 by David Patey and Peter Dyson at Middlesex Hospital in London as a less disfiguring alternative to the more extensive radical mastectomy, which removes both pectoral muscles.[16] Unlike its historical predecessor, the radical mastectomy, MRM maintains the structural integrity of the chest wall musculature to minimize functional deficits.[3] Key advantages of MRM include significantly reduced postoperative morbidity compared to radical mastectomy, such as lower rates of lymphedema (approximately 20-25% versus nearly 50%) and improved shoulder function due to preservation of the pectoralis muscles, which supports better arm mobility and range of motion.[64] Oncologically, MRM provides equivalent local control and survival outcomes to the radical procedure, with no significant differences in recurrence or overall survival rates observed in long-term studies.[65] These benefits stem from adequate tumor resection and lymph node clearance without the added trauma of muscle excision.[66] Today, MRM remains the standard for the majority of mastectomy cases requiring axillary lymph node dissection.[67] Its design facilitates immediate breast reconstruction, often using implants or autologous tissue, which can be performed in the same operation to improve cosmetic and psychological outcomes for patients.[68]Breast-conserving surgery and systemic therapies

Breast-conserving surgery (BCS), also known as lumpectomy, involves the removal of the primary tumor and a margin of surrounding healthy tissue, followed by adjuvant radiation therapy to the breast. This approach aims to preserve the breast's natural appearance while effectively treating early-stage breast cancer. A 2024 meta-analysis of over 900,000 patients with early-stage breast cancer demonstrated that BCS with adjuvant radiotherapy yields comparable or superior overall survival compared to mastectomy, with a pooled hazard ratio of 0.72 favoring BCS.[69] Systemic therapies, including neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy, endocrine therapy, and targeted agents such as HER2 inhibitors (e.g., trastuzumab), play a crucial role in downstaging tumors and expanding eligibility for BCS. Neoadjuvant therapy, administered before surgery, shrinks tumors in approximately 70-75% of initially ineligible cases, converting them to candidates for breast conservation. For instance, in a cohort of 600 patients deemed ineligible for BCS due to tumor size, 75% became eligible post-neoadjuvant chemotherapy, with 68% ultimately undergoing successful BCS. Adjuvant therapies post-surgery further reduce recurrence risk by targeting microscopic disease, with hormone therapy benefiting estrogen receptor-positive cases and targeted agents improving outcomes in HER2-positive subtypes.[70] Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) has largely replaced complete axillary lymph node dissection in early-stage breast cancer, minimizing morbidity while accurately staging the axilla. The 2025 ASCO guideline update recommends SLNB over dissection for patients with 1-2 positive sentinel nodes undergoing BCS with whole-breast radiation, citing high-quality evidence from trials like ACOSOG Z0011 that show no survival detriment and reduced complications such as lymphedema. De-escalation strategies, including omission of SLNB in select postmenopausal patients aged 50 or older with low-risk, hormone receptor-positive tumors, further align with efforts to balance oncologic efficacy and quality of life.[71]References

- https://acsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/1097-0142(19850215)55:4<880::AID-CNCR2820550429>3.0.CO;2-4