Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Dissection

View on Wikipedia| Dissection | |

|---|---|

Dissection of a pregnant rat in a biology class | |

| |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D004210 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Dissection (from Latin dissecare "to cut to pieces"; also called anatomization) is the dismembering of the body of a deceased animal or plant to study its anatomical structure. Autopsy is used in pathology and forensic medicine to determine the cause of death in humans. Less extensive dissection of plants and smaller animals preserved in a formaldehyde solution is typically carried out or demonstrated in biology and natural science classes in middle school and high school, while extensive dissections of cadavers of adults and children, both fresh and preserved are carried out by medical students in medical schools as a part of the teaching in subjects such as anatomy, pathology and forensic medicine. Consequently, dissection is typically conducted in a morgue or in an anatomy lab.

Dissection has been used for centuries to explore anatomy. Objections to the use of cadavers have led to the use of alternatives including virtual dissection of computer models.

In the field of surgery, the term "dissection" or "dissecting" means more specifically the practice of separating an anatomical structure (an organ, nerve or blood vessel) from its surrounding connective tissue in order to minimize unwanted damage during a surgical procedure.

Overview

[edit]Plant and animal bodies are dissected to analyze the structure and function of its components. Dissection is practised by students in courses of biology, botany, zoology, and veterinary science, and sometimes in arts studies. In medical schools, students dissect human cadavers to learn anatomy.[1] Zoötomy is sometimes used to describe "dissection of an animal".

Human dissection

[edit]A key principle in the dissection of human cadavers (sometimes called androtomy) is the prevention of human disease to the dissector. Prevention of transmission includes the wearing of protective gear, ensuring the environment is clean, dissection technique[2] and pre-dissection tests to specimens for the presence of HIV and hepatitis viruses.[3] Specimens are dissected in morgues or anatomy labs. When provided, they are evaluated for use as a "fresh" or "prepared" specimen.[3] A "fresh" specimen may be dissected within some days, retaining the characteristics of a living specimen, for the purposes of training. A "prepared" specimen may be preserved in solutions such as formalin and pre-dissected by an experienced anatomist, sometimes with the help of a diener.[3] This preparation is sometimes called prosection.[4]

Most dissection involves the careful isolation and removal of individual organs, called the Virchow technique.[2][5] An alternative more cumbersome technique involves the removal of the entire organ body, called the Letulle technique. This technique allows a body to be sent to a funeral director without waiting for the sometimes time-consuming dissection of individual organs.[2] The Rokitansky method involves an in situ dissection of the organ block, and the technique of Ghon involves dissection of three separate blocks of organs - the thorax and cervical areas, gastrointestinal and abdominal organs, and urogenital organs.[2][5] Dissection of individual organs involves accessing the area in which the organ is situated, and systematically removing the anatomical connections of that organ to its surroundings. For example, when removing the heart, connects such as the superior vena cava and inferior vena cava are separated. If pathological connections exist, such as a fibrous pericardium, then this may be deliberately dissected along with the organ.[2]

Autopsy and necropsy

[edit]Dissection is used to help to determine the cause of death in autopsy (called necropsy in other animals) and is an intrinsic part of forensic medicine.[6]

History

[edit]

Classical antiquity

[edit]Human dissections were carried out by the Greek physicians Herophilus of Chalcedon and Erasistratus of Chios in the early part of the third century BC.[7][8] Before then, animal dissection had been carried out systematically starting from the fifth century BC.[9] During this period, the first exploration into full human anatomy was performed rather than a base knowledge gained from 'problem-solution' delving.[10] While there was a deep taboo in Greek culture concerning human dissection, there was at the time a strong push by the Ptolemaic government to build Alexandria into a hub of scientific study.[10] For a time, Roman law forbade dissection and autopsy of the human body,[11] so anatomists relied on the cadavers of animals or made observations of human anatomy from injuries of the living. Galen, for example, dissected the Barbary macaque and other primates, assuming their anatomy was basically the same as that of humans, and supplemented these observations with knowledge of human anatomy which he acquired while tending to wounded gladiators.[8][12][13][14]

Celsus wrote in On Medicine I Proem 23, "Herophilus and Erasistratus proceeded in by far the best way: they cut open living men - criminals they obtained out of prison from the kings and they observed, while their subjects still breathed, parts that nature had previously hidden, their position, color, shape, size, arrangement, hardness, softness, smoothness, points of contact, and finally the processes and recesses of each and whether any part is inserted into another or receives the part of another into itself."

Galen was another such writer who was familiar with the studies of Herophilus and Erasistratus.

India

[edit]

The ancient societies that were rooted in India left behind artwork on how to kill animals during a hunt.[15] The images showing how to kill most effectively depending on the game being hunted relay an intimate knowledge of both external and internal anatomy as well as the relative importance of organs.[15] The knowledge was mostly gained through hunters preparing the recently captured prey. Once the roaming lifestyle was no longer necessary it was replaced in part by the civilization that formed in the Indus Valley. Unfortunately, there is little that remains from this time to indicate whether or not dissection occurred, the civilization was lost to the Aryan people migrating.[15]

Early in the history of India (2nd to 3rd century), the Arthashastra described the 4 ways that death can occur and their symptoms: drowning, hanging, strangling, or asphyxiation.[16] According to that source, an autopsy should be performed in any case of untimely demise.[16]

The practice of dissection flourished during the 7th and 8th century. It was under their rule that medical education was standardized. This created a need to better understand human anatomy, so as to have educated surgeons. Dissection was limited by the religious taboo on cutting the human body. This changed the approach taken to accomplish the goal. The process involved the loosening of the tissues in streams of water before the outer layers were sloughed off with soft implements to reach the musculature. To perfect the technique of slicing, the prospective students used gourds and squash. These techniques of dissection gave rise to an advanced understanding of the anatomy and the enabled them to complete procedures used today, such as rhinoplasty.[15]

During medieval times the anatomical teachings from India spread throughout the known world; however, the practice of dissection was stunted by Islam.[15] The practice of dissection at a university level was not seen again until 1827, when it was performed by the student Pandit Madhusudan Gupta.[15] Through the 1900s, the university teachers had to continually push against the social taboos of dissection, until around 1850 when the universities decided that it was more cost effective to train Indian doctors than bring them in from Britain.[15] Indian medical schools were, however, training female doctors well before those in England.[15]

The current state of dissection in India is deteriorating. The number of hours spent in dissection labs during medical school has decreased substantially over the last twenty years.[15] The future of anatomy education will probably be an elegant mix of traditional methods and integrative computer learning.[15] The use of dissection in early stages of medical training has been shown more effective in the retention of the intended information than their simulated counterparts.[15] However, there is use for the computer-generated experience as review in the later stages.[15] The combination of these methods is intended to strengthen the students' understanding and confidence of anatomy, a subject that is infamously difficult to master.[15] There is a growing need for anatomist—seeing as most anatomy labs are taught by graduates hoping to complete degrees in anatomy—to continue the long tradition of anatomy education.[15]

Islamic world

[edit]

From the beginning of the Islamic faith in 610 A.D.,[17] Shari'ah law has applied to a greater or lesser extent within Muslim countries,[17] supported by Islamic scholars such as Al-Ghazali.[18] Islamic physicians such as Ibn Zuhr (Avenzoar) (1091–1161) in Al-Andalus,[19] Saladin's physician Ibn Jumay during the 12th century, Abd el-Latif in Egypt c. 1200,[20] and Ibn al-Nafis in Syria and Egypt in the 13th century may have practiced dissection,[18][21][22] but it remains ambiguous whether or not human dissection was practiced. Ibn al-Nafis, a physician and Muslim jurist, suggested that the "precepts of Islamic law have discouraged us from the practice of dissection, along with whatever compassion is in our temperament",[3] indicating that while there was no law against it, it was nevertheless uncommon. Islam dictates that the body be buried as soon as possible, barring religious holidays, and that there be no other means of disposal such as cremation.[17] Prior to the 10th century, dissection was not performed on human cadavers.[17] The book Al-Tasrif, written by Al-Zahrawi in 1000 A.D., details surgical procedure that differed from the previous standards.[23] The book was an educational text of medicine and surgery which included detailed illustrations.[23] It was later translated and took the place of Avicenna's The Canon of Medicine as the primary teaching tool in Europe from the 12th century to the 17th century.[23] There were some that were willing to dissect humans up to the 12th century, for the sake of learning, after which it was forbidden. This attitude remained constant until 1952, when the Islamic School of Jurisprudence in Egypt ruled that "necessity permits the forbidden".[17] This decision allowed for the investigation of questionable deaths by autopsy.[17] In 1982, the decision was made by a fatwa that if it serves justice, autopsy is worth the disadvantages.[17] Though Islam now approves of autopsy, the Islamic public still disapproves. Autopsy is prevalent in most Muslim countries for medical and judicial purposes.[17] In Egypt it holds an important place within the judicial structure, and is taught at all the country's medical universities.[17] In Saudi Arabia, whose law is completely dictated by Shari'ah, autopsy is viewed poorly by the population but can be compelled in criminal cases;[17] human dissection is sometimes found at university level.[17] Autopsy is performed for judicial purposes in Qatar and Tunisia.[17] Human dissection is present in the modern day Islamic world, but is rarely published on due to the religious and social stigma.[17]

Tibet

[edit]Tibetan medicine developed a rather sophisticated knowledge of anatomy, acquired from long-standing experience with human dissection. Tibetans had adopted the practice of sky burial because of the country's hard ground, frozen for most of the year, and the lack of wood for cremation. A sky burial begins with a ritual dissection of the deceased, and is followed by the feeding of the parts to vultures on the hill tops. Over time, Tibetan anatomical knowledge found its way into Ayurveda[24] and to a lesser extent into Chinese medicine.[25][26]

Christian Europe

[edit]

Throughout the history of Christian Europe, the dissection of human cadavers for medical education has experienced various cycles of legalization and proscription in different countries. Dissection was rare during the Middle Ages, but it was practised,[27] with evidence from at least as early as the 13th century.[28][29][30] The practice of autopsy in Medieval Western Europe is "very poorly known" as few surgical texts or conserved human dissections have survived.[31] A modern Jesuit scholar has claimed that the Christian theology contributed significantly to the revival of human dissection and autopsy by providing a new socio-religious and cultural context in which the human cadaver was no longer seen as sacrosanct.[28]

A non-existent edict[32] Ecclesia abhorret a sanguine of the 1163 Council of Tours and an early 14th-century decree of Pope Boniface VIII have mistakenly been identified as prohibiting dissection and autopsy; misunderstanding or extrapolation from these edicts may have contributed to reluctance to perform such procedures.[33][a] The Middle Ages witnessed the revival of an interest in medical studies, including human dissection and autopsy.[8][34]

Frederick II (1194–1250), the Holy Roman Emperor, decreed that any that were studying to be a physician or a surgeon must attend a human dissection, which would be held no less than every five years.[10] Some European countries began legalizing the dissection of executed criminals for educational purposes in the late 13th and early 14th centuries. Mondino de Luzzi carried out the first recorded public dissection around 1315.[10] At this time, autopsies were carried out by a team consisting of a Lector, who lectured; the Sector, who did the dissection; and the Ostensor, who pointed to features of interest.[10]

The Italian Galeazzo di Santa Sofia made the first public dissection north of the Alps in Vienna in 1404.[35]

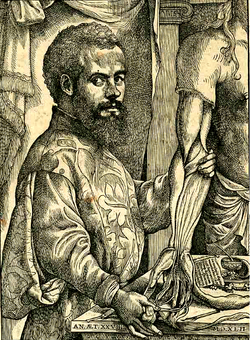

Vesalius in the 16th century carried out numerous dissections in his extensive anatomical investigations. He was attacked frequently for his disagreement with Galen's opinions on human anatomy. Vesalius was the first to lecture and dissect the cadaver simultaneously.[10][36]

The Catholic Church is known to have ordered an autopsy on conjoined twins Joana and Melchiora Ballestero in Hispaniola in 1533 to determine whether they shared a soul. They found that there were two distinct hearts, and hence two souls, based on the ancient Greek philosopher Empedocles, who believed the soul resided in the heart.[37]

Human dissection was also practised by Renaissance artists. Though most chose to focus on the external surfaces of the body, some like Michelangelo Buonarotti, Antonio del Pollaiuolo, Baccio Bandinelli, and Leonardo da Vinci sought a deeper understanding. However, there were no provisions for artists to obtain cadavers, so they had to resort to unauthorised means, as indeed anatomists sometimes did, such as grave robbing, body snatching, and murder.[10]

Anatomization was sometimes ordered as a form of punishment, as, for example, in 1806 to James Halligan and Dominic Daley after their public hanging in Northampton, Massachusetts.[38]

In modern Europe, dissection is routinely practised in biological research and education, in medical schools, and to determine the cause of death in autopsy. It is generally considered a necessary part of learning and is thus accepted culturally. It sometimes attracts controversy, as when Odense Zoo decided to dissect lion cadavers in public before a "self-selected audience".[39][40]

Britain

[edit]

In Britain, dissection remained entirely prohibited from the end of the Roman conquest and through the Middle Ages to the 16th century, when a series of royal edicts gave specific groups of physicians and surgeons some limited rights to dissect cadavers. The permission was quite limited: by the mid-18th century, the Royal College of Physicians and Company of Barber-Surgeons were the only two groups permitted to carry out dissections, and had an annual quota of ten cadavers between them. As a result of pressure from anatomists, especially in the rapidly growing medical schools, the Murder Act 1752 allowed the bodies of executed murderers to be dissected for anatomical research and education. By the 19th century this supply of cadavers proved insufficient, as the public medical schools were growing, and the private medical schools lacked legal access to cadavers. A thriving black market arose in cadavers and body parts, leading to the creation of the profession of body snatching, and the infamous Burke and Hare murders in 1828, when 16 people were murdered for their cadavers, to be sold to anatomists. The resulting public outcry led to the passage of the Anatomy Act 1832, which increased the legal supply of cadavers for dissection.[41]

By the 21st century, the availability of interactive computer programs and changing public sentiment led to renewed debate on the use of cadavers in medical education. The Peninsula College of Medicine and Dentistry in the UK, founded in 2000, became the first modern medical school to carry out its anatomy education without dissection.[42]

United States

[edit]

In the United States, dissection of frogs became common in college biology classes from the 1920s, and were gradually introduced at earlier stages of education. By 1988, some 75 to 80 percent of American high school biology students were participating in a frog dissection, with a trend towards introduction in elementary schools. The frogs are most commonly from the genus Rana. Other popular animals for high-school dissection at the time of that survey were, among vertebrates, fetal pigs, perch, and cats; and among invertebrates, earthworms, grasshoppers, crayfish, and starfish.[43] About six million animals are dissected each year in United States high schools (2016), not counting medical training and research. Most of these are purchased already dead from slaughterhouses and farms.[44]

Dissection in U.S. high schools became prominent in 1987, when a California student, Jenifer Graham, sued to require her school to let her complete an alternative project. The court ruled that mandatory dissections were permissible, but that Graham could ask to dissect a frog that had died of natural causes rather than one that was killed for the purposes of dissection; the practical impossibility of procuring a frog that had died of natural causes in effect let Graham opt out of the required dissection. The suit gave publicity to anti-dissection advocates. Graham appeared in a 1987 Apple Computer commercial for the virtual-dissection software Operation Frog.[45][46] The state of California passed a Student's Rights Bill in 1988 requiring that objecting students be allowed to complete alternative projects.[47] Opting out of dissection increased through the 1990s.[48]

In the United States, 17 states[b] along with Washington, D.C. have enacted dissection-choice laws or policies that allow students in primary and secondary education to opt out of dissection. Other states including Arizona, Hawaii, Minnesota, Texas, and Utah have more general policies on opting out on moral, religious, or ethical grounds.[49] To overcome these concerns, J. W. Mitchell High School in New Port Richey, Florida, in 2019 became the first US high school to use synthetic frogs for dissection in its science classes, instead of preserved real frogs.[50][51][52]

As for the dissection of cadavers in undergraduate and medical school, traditional dissection is supported by professors and students, with some opposition, limiting the availability of dissection. Upper-level students who have experienced this method along with their professors agree that "Studying human anatomy with colorful charts is one thing. Using a scalpel and an actual, recently-living person is an entirely different matter."[53]

Acquisition of cadavers

[edit]The way in which cadaveric specimens are obtained differs greatly according to country.[54] In the UK, donation of a cadaver is wholly voluntary. Involuntary donation plays a role in about 20 percent of specimens in the US and almost all specimens donated in some countries such as South Africa and Zimbabwe.[54] Countries that practice involuntary donation may make available the bodies of dead criminals or unclaimed or unidentified bodies for the purposes of dissection.[54] Such practices may lead to a greater proportion of the poor, homeless and social outcasts being involuntarily donated.[54] Cadavers donated in one jurisdiction may also be used for the purposes of dissection in another, whether across states in the US,[3] or imported from other countries, such as with Libya.[54] As an example of how a cadaver is donated voluntarily, a funeral home in conjunction with a voluntary donation program identifies a body who is part of the program. After broaching the subject with relatives in a diplomatic fashion, the body is then transported to a registered facility. The body is tested for the presence of HIV and hepatitis viruses. It is then evaluated for use as a "fresh" or "prepared" specimen.[3]

Disposal of specimens

[edit]Cadaveric specimens for dissection are, in general, disposed of by cremation. The deceased may then be interred at a local cemetery. If the family wishes, the ashes of the deceased are then returned to the family.[3] Many institutes have local policies to engage, support and celebrate the donors. This may include the setting up of local monuments at the cemetery.[3]

Use in education

[edit]

Human cadavers are often used in medicine to teach anatomy or surgical instruction.[3][54] Cadavers are selected according to their anatomy and availability. They may be used as part of dissection courses involving a "fresh" specimen so as to be as realistic as possible—for example, when training surgeons.[3] Cadavers may also be pre-dissected by trained instructors. This form of dissection involves the preparation and preservation of specimens for a longer time period and is generally used for the teaching of anatomy.[3]

Alternatives

[edit]Some alternatives to dissection may present educational advantages over the use of animal cadavers, while eliminating perceived ethical issues.[55] These alternatives include computer programs, lectures, three dimensional models, films, and other forms of technology. Concern for animal welfare is often at the root of objections to animal dissection.[56] Studies show that some students reluctantly participate in animal dissection out of fear of real or perceived punishment or ostracism from their teachers and peers, and many do not speak up about their ethical objections.[57][58]

One alternative to the use of cadavers is computer technology. At Stanford Medical School, software combines X-ray, ultrasound and MRI imaging for display on a screen as large as a body on a table.[59] In a variant of this, a "virtual anatomy" approach being developed at New York University, students wear three dimensional glasses and can use a pointing device to "[swoop] through the virtual body, its sections as brightly colored as living tissue." This method is claimed to be "as dynamic as Imax [cinema]".[60]

Advantages and disadvantages

[edit]Proponents of animal-free teaching methodologies argue that alternatives to animal dissection can benefit educators by increasing teaching efficiency and lowering instruction costs while affording teachers an enhanced potential for the customization and repeat-ability of teaching exercises. Those in favor of dissection alternatives point to studies which have shown that computer-based teaching methods "saved academic and nonacademic staff time ... were considered to be less expensive and an effective and enjoyable mode of student learning [and] ... contributed to a significant reduction in animal use" because there is no set-up or clean-up time, no obligatory safety lessons, and no monitoring of misbehavior with animal cadavers, scissors, and scalpels.[61][62][63]

With software and other non-animal methods, there is also no expensive disposal of equipment or hazardous material removal. Some programs also allow educators to customize lessons and include built-in test and quiz modules that can track student performance. Furthermore, animals (whether dead or alive) can be used only once, while non-animal resources can be used for many years—an added benefit that could result in significant cost savings for teachers, school districts, and state educational systems.[61]

Several peer-reviewed comparative studies examining information retention and performance of students who dissected animals and those who used an alternative instruction method have concluded that the educational outcomes of students who are taught basic and advanced biomedical concepts and skills using non-animal methods are equivalent or superior to those of their peers who use animal-based laboratories such as animal dissection.[64][65]

Some reports state that students' confidence, satisfaction, and ability to retrieve and communicate information was much higher for those who participated in alternative activities compared to dissection. Three separate studies at universities across the United States found that students who modeled body systems out of clay were significantly better at identifying the constituent parts of human anatomy than their classmates who performed animal dissection.[66][67][68]

Another study found that students preferred using clay modeling over animal dissection and performed just as well as their cohorts who dissected animals.[69]

In 2008, the National Association of Biology Teachers (NABT) affirmed its support for classroom animal dissection stating that they "Encourage the presence of live animals in the classroom with appropriate consideration to the age and maturity level of the students ... NABT urges teachers to be aware that alternatives to dissection have their limitations. NABT supports the use of these materials as adjuncts to the educational process but not as exclusive replacements for the use of actual organisms."[70]

The National Science Teachers Association (NSTA) "supports including live animals as part of instruction in the K-12 science classroom because observing and working with animals firsthand can spark students' interest in science as well as a general respect for life while reinforcing key concepts" of biological sciences. NSTA also supports offering dissection alternatives to students who object to the practice.[71]

The NORINA database lists over 3,000 products which may be used as alternatives or supplements to animal use in education and training.[72][non-primary source needed] These include alternatives to dissection in schools. InterNICHE has a similar database and a loans system.[73][non-primary source needed]

Additional images

[edit]-

Dissection of a human cheek from Gray's Anatomy (1918)

-

Dissection of a spiny dogfish

-

Dissection of human axilla

-

Human abdomen and thorax

-

Cow brain prepared for dissection

-

Dissection in a secondary school GCSE class

-

Technique of dissection and glycerination in bovine articulation (tarsus)

See also

[edit]- 1788 Doctors' riot in New York City

- Vivisection

- Forensics

- Andreas Vesalius, founder of modern anatomy

- Jean-Joseph Sue, 18th century surgeon and anatomist

Notes

[edit]- ^ "the pope did not forbid anatomical dissections but only the dissections performed with the purpose of preserving the bodies for distant burial"[28]

- ^ California, Connecticut, D.C., Florida, Illinois, Louisiana, Maine, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Virginia all have statewide laws or department of education policies that allow students to opt out.

References

[edit]- ^ McLachlan, John C.; Patten, Debra (17 February 2006). "Anatomy teaching: ghosts of the past, present and future". Medical Education. 40 (3): 243–253. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02401.x. PMID 16483327. S2CID 30909540.

- ^ a b c d e Waters, Brenda L. (2009). "2. Principles of Dissection". In Waters, Brenda L (ed.). Handbook of Autopsy Practice - Springer. pp. 11–12. doi:10.1007/978-1-59745-127-7. ISBN 978-1-58829-841-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Robertson, Hugh J.; Paige, John T.; Bok, Leonard (2012-07-12). Simulation in Radiology. OUP USA. pp. 15–20. ISBN 978-0-19-976462-4.

- ^ "prosect - definition of prosect in English from the Oxford dictionary". www.oxforddictionaries.com. Archived from the original on November 6, 2015. Retrieved 2016-05-10.

- ^ a b Connolly, Andrew J.; Finkbeiner, Walter E.; Ursell, Philip C.; Davis, Richard L. (2015-09-23). Autopsy Pathology: A Manual and Atlas. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 978-0-323-28780-7.

- ^ "Interactive Autopsy". Australian Museum. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- ^ von Staden, Heinrich (1992). "The discovery of the body: Human dissection and its cultural contexts in ancient Greece". The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine. 65 (3): 223–241. PMC 2589595. PMID 1285450.

- ^ a b c Brenna, Connor T. A. (2021). "Bygone theatres of events: A history of human anatomy and dissection". The Anatomical Record. 305 (4): 2–5. doi:10.1002/ar.24764. ISSN 1932-8494. PMID 34551186. S2CID 237608991.

- ^ See Bubb 2022: 12. Claire Bubb. 2022. Dissection in Classical Antiquity: A Social and Medical History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ghosh, Sanjib Kumar (2015-09-01). "Human cadaveric dissection: a historical account from ancient Greece to the modern era". Anatomy & Cell Biology. 48 (3): 153–169. doi:10.5115/acb.2015.48.3.153. ISSN 2093-3665. PMC 4582158. PMID 26417475.

- ^ Aufderheide, Arthur C. (2003). The Scientific Study of Mummies. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-521-17735-1.

Tragically, the prohibition of human dissection by Rome in 150 BC arrested this progress and few of their findings survived.

- ^ Nutton, Vivian, 'The Unknown Galen', (2002), p. 89

- ^ Von Staden, Heinrich, Herophilus (1989), p. 140

- ^ Lutgendorf, Philip, Hanuman's Tale: The Messages of a Divine Monkey (2007), p. 348

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Jacob, Tony (2013). "History of teaching anatomy in India: from ancient to modern times". Anatomical Sciences Education. 6 (5): 351–8. doi:10.1002/ase.1359. PMID 23495119. S2CID 25807230.

- ^ a b Mathiharan, Karunakaran (September 2005). "Origin and Development of Forensic Medicine in India". The American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology. 26 (3): 254–260. doi:10.1097/01.paf.0000163839.24718.b8. PMID 16121082. S2CID 29095914.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Mohammed, Madadin; Kharoshah, Magdy (2014). "Autopsy in Islam and current practice in Arab Muslim countries". Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine. 23: 80–3. doi:10.1016/j.jflm.2014.02.005. PMID 24661712.

- ^ a b Savage-Smith, Emilie (1995). "Attitudes toward dissection in medieval Islam". Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. 50 (1): 67–110. doi:10.1093/jhmas/50.1.67. PMID 7876530.

- ^ Ibn Zuhr and the Progress of Surgery, http://muslimheritage.com/article/ibn-zuhr-and-progress-surgery

- ^ Emilie Savage-Smith (1996), "Medicine", in Roshdi Rashed, ed., Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science, Vol. 3, pp. 903–962 [951–952]. Routledge, London and New York.

- ^ Al-Dabbagh, S.A. (1978). "Ibn Al-Nafis and the pulmonary circulation". The Lancet. 1 (8074): 1148. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(78)90318-5. PMID 77431. S2CID 43154531.

- ^ Hajar A Hajar Albinali (2004). "Traditional Medicine Among Gulf Arabs, Part II: Blood-letting". Heart Views. 5 (2): 74–85.

- ^ a b c Chavoushi, Seyed Hadi; Ghabili, Kamyar; Kazemi, Abdolhassan; Aslanabadi, Arash; Babapour, Sarah; Ahmedli, Rafail; Golzari, Samad E.J. (August 2012). "Surgery for Gynecomastia in the Islamic Golden Age: Al-Tasrif of Al-Zahrawi (936-1013 AD)". ISRN Surgery. 2012 934965. doi:10.5402/2012/934965. PMC 3459224. PMID 23050167.

- ^ Wujastyk, Dominik (2001). The Roots of Ayurveda. Penguin Classics.

- ^ Strober, Deborah Hart; Strober, Gerald S. (2005). His Holiness the Dalai Lama: The Oral Biography. Wiley. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-471-68001-7.

- ^ Svoboda, Robert E. (1996). Tao and Dharma: Chinese Medicine and Ayurveda. p. 89.

- ^ Classen, Albrecht (2016). Death in the Middle Ages and Early Modern Times: The Material and Spiritual Conditions of the Culture of Death. Walter de Gruyter. p. 388. ISBN 978-3-11-043697-6.

- ^ a b c P. Prioreschi, "Determinants of the revival of dissection of the human body in the Middle Ages", Medical Hypotheses (2001) 56(2), 229–234

- ^ "In the 13th century, the realisation that human anatomy could best be taught by dissection of the human body resulted in its legalisation of publicly dissecting criminals in some European countries between 1283 and 1365" – this was, however, still contrary to the edicts of the Church. Philip Cheung, "Public Trust in Medical Research?" (2007), page 36

- ^ "Indeed, very early in the thirteenth century, a religious official, namely, Pope Innocent III (1198–1216), ordered the postmortem autopsy of a person whose death was suspicious". Toby Huff, The Rise Of Modern Science (2003), page 195

- ^ Charlier, Philippe; Huynh-Charlier, Isabelle; Poupon, Joël; Lancelot, Eloïse; Campos, Paula F.; Favier, Dominique; et al. (May 2014). "A glimpse into the early origins of medieval anatomy through the oldest conserved human dissection (Western Europe, 13th c. A.D.)". Archives of Medical Science. 10 (2): 366–373. doi:10.5114/aoms.2013.33331. PMC 4042035. PMID 24904674.

- ^ Charles H. Talbot. Medicine in Medieval England. London: Oldbourne, 1967. p. 55, n. 13.

- ^ "While during this period the Church did not forbid human dissections in general, certain edicts were directed at specific practices. These included the Ecclesia Abhorret a Sanguine in 1163 by the Council of Tours and Pope Boniface VIII's command to terminate the practice of dismemberment of slain crusaders' bodies and boiling the parts to enable defleshing for return of their bones. Such proclamations were commonly misunderstood as a ban on all dissection of either living persons or cadavers (Rogers & Waldron, 1986)[clarification needed], and progress in anatomical knowledge by human dissection did not thrive in that intellectual climate." Arthur Aufderheide, The Scientific Study of Mummies (2003), p. 5

- ^ "Current scholarship reveals that Europeans had considerable knowledge of human anatomy, not just that based on Galen and his animal dissections. For the Europeans had performed significant numbers of human dissections, especially postmortem autopsies during this era", "Many of the autopsies were conducted to determine whether or not the deceased had died of natural causes (disease) or whether there had been foul play, poisoning, or physical assault. Indeed, very early in the thirteenth century, a religious official, namely, Pope Innocent III (1198–1216), ordered the postmortem autopsy of a person whose death was suspicious". Toby Huff, The Rise Of Modern Science (2003), p. 195

- ^ Regal, Wolfgang; Nanut, Michael (December 13, 2007). Vienna – A Doctor's Guide: 15 walking tours through Vienna's medical history. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 7. ISBN 978-3-211-48952-9.

- ^ C. D. O'Malley, Andreas Vesalius' Pilgrimage, Isis 45:2, 1954

- ^ Freedman, David H. (September 2012). "20 Things you didn't know about autopsies". Discovery. 9: 72.

- ^ Brown, Richard D. (June 2011). "'Tried, Convicted, and Condemned, in Almost Every Bar-room and Barber's Shop': Anti-Irish Prejudice in the Trial of Dominic Daley and James Halligan, Northampton, Massachusetts, 1806". The New England Quarterly. 84 (2): 205–233. doi:10.1162/tneq_a_00087. S2CID 57560527.

- ^ "Odense Zoo animal dissections: EAZA response". European Association of Zoos and Aquaria. Archived from the original on 13 May 2016. Retrieved 15 May 2016.

- ^ "Animals used for scientific purposes". European Union. Retrieved 15 May 2016.

- ^ Cheung, pp. 37–44

- ^ Cheung, pp. 33, 35

- ^ Orlans, F. Barbara; Beauchamp, Tom L.; Dresser, Rebecca; Morton, David B.; Gluck, John P. (1998). The Human Use of Animals. Oxford University Press. pp. 213. ISBN 978-0-19-511908-4.

- ^ "Dissection". American Anti-Vivisection Society. 2016. Retrieved 16 February 2016.

- ^ Howard Rosenberg: Apple Computer's 'Frog' Ad Is Taken Off the Air. Los Angeles Times, November 10, 1987.

- ^ F. Barbara Orlans; Tom L. Beauchamp; Rebecca Dresser; David B. Morton; John P. Gluck (1998). The Human Use of Animals. Oxford University Press. p. 210. ISBN 978-0-19-511908-4.

- ^ Orlans et al., pp. 209–211

- ^ Johnson, Dirk (May 29, 1997). "Frogs' Best Friends: Students Who Won't Dissect Them". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ^ "Your Right Not to Dissect". PETA2.

- ^ Aaro, David (November 30, 2019). "Florida high school first in world to use synthetic frogs for dissection". Fox News. Retrieved November 30, 2019.

- ^ Elassar, Alaa (November 30, 2019). "A Florida high school is the first in the world to provide synthetic frogs for students to dissect". CNN. Retrieved November 30, 2019.

- ^ Lewis, Sophie (November 26, 2019). "Florida high school introduces synthetic frogs for science class dissection". CBS News. Retrieved November 30, 2019.

- ^ Jenner, Andrew (2012). "EMU News". EMU's Cadaver Dissection Gives Pre-Med Students Big Advantage. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f Gangata, Hope; Ntaba, Phatheka; Akol, Princess; Louw, Graham (2010-08-01). "The reliance on unclaimed cadavers for anatomical teaching by medical schools in Africa". Anatomical Sciences Education. 3 (4): 174–183. doi:10.1002/ase.157. ISSN 1935-9780. PMID 20544835. S2CID 22596215.

- ^ Balcombe, Jonathan (2001). "Dissection: The Scientific Case for Alternatives". Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science. 4 (2): 117–126. doi:10.1207/S15327604JAWS0402_3. S2CID 143465900. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- ^ Stainsstreet, M; Spofforth, N; Williams, T (1993). "Attitudes of undergraduate students to the uses of animals". Studies in Higher Education. 18 (2): 177–196. doi:10.1080/03075079312331382359.

- ^ Oakley, J (2012). "Dissection and choice in the science classroom: student experiences, teacher responses, and a critical analysis of the right to refuse". Journal of Teaching and Learning. 8 (2). doi:10.22329/jtl.v8i2.3349.

- ^ Oakley, J (2013). ""I didn't feel right about animal dissection": Dissection objectors share their science class experiences". Society & Animals. 21 (1): 360–378. doi:10.1163/15685306-12341267.

- ^ White, Tracie (2011). "Body image: Computerized table lets students do virtual dissection". Stanford Medicine: News Center. Retrieved 20 February 2016.

- ^ Singer, Natasha (7 January 2012). "The Virtual Anatomy, Ready for Dissection". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- ^ a b Dewhurt, D; Jenkinson, L (1995). "The impact of computer-based alternatives on the use of animals in undergraduate teaching: A pilot study". ATLA. 23 (4): 521–530.

- ^ Predavec, M. (2001). "Evaluation of E-Rat, a computer-based rat dissection, in terms of student learning outcomes". Journal of Biological Education. 35 (2): 75–80. doi:10.1080/00219266.2000.9655746. S2CID 85201408.

- ^ Youngblut, C. (2001). "Use of multimedia technology to provide solutions to existing curriculum problems: Virtual frog dissection". Doctoral Dissertation. Bibcode:2001PhDT........42Y.

- ^ Patronek, G. J.; Rauch, A (2007). "Systematic review of comparative studies examining alternatives to the harmful use of animals in biomedical education". Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 230 (1): 37–43. doi:10.2460/javma.230.1.37. PMID 17199490. S2CID 5164145.

- ^ Knight, A. (2007). "The effectiveness of humane teaching methods in veterinary education". ALTEX. 24 (2): 91–109. doi:10.14573/altex.2007.2.91. PMID 17728975.

- ^ Waters, J. R.; Van Meter, P.; Perrotti, W; Drogo, S; Cyr, R. J. (2005). "Cat dissection vs. sculpting human structures in clay: An analysis of two approaches to undergraduate human anatomy laboratory education". Advances in Physiology Education. 29 (1): 27–34. doi:10.1152/advan.00033.2004. PMID 15718380. S2CID 28694409.

- ^ Motoike, H. K.; O'Kane, R. L.; Lenchner, E.; Haspel, C. (2009). "Clay modeling as a method to learn human muscles: A community college study". Anatomical Sciences Education. 2 (1): 19–23. doi:10.1002/ase.61. PMID 19189347. S2CID 28441790.

- ^ Waters, J. R.; Van Meter, P.; Perrotti, W.; Drogo, S.; Cyr, R. J. (2011). "Human clay models versus cat dissection: How the similarity between the classroom and the exam affects student performance". Advances in Physiology Education. 35 (2): 227–236. doi:10.1152/advan.00030.2009. PMID 21652509.

- ^ DeHoff, M. E.; Clark, K. L; Meganathan, K. (2011). "Learning outcomes and student perceived value of clay modeling and cat dissection in undergraduate human anatomy and physiology". Advances in Physiology Education. 35 (1): 68–75. doi:10.1152/advan.00094.2010. PMID 21386004. S2CID 19112983.

- ^ "The Use of Animals in Biology Education". Position Statements: National Association of Biology Teachers. National Association of Biology Teachers. Archived from the original on 13 May 2015. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

- ^ "NSTA Position Statement: Responsible Use of Live Animals and Dissection in the Science Classroom". National Science Teachers Association. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

- ^ NORINA

- ^ InterNICHE

Further reading

[edit]- C. Celsus, On Medicine, I, Proem 23, 1935, translated by W. G. Spencer (Loeb Classics Library, 1992).

- Claire Bubb. 2022. Dissection in Classical Antiquity: A Social and Medical History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

External links

[edit]- How to dissect a frog

- Dissection Alternatives

- Human Dissections

- Virtual Frog Dissection

- Alternatives To Animal Dissection in School Science Classes

- Research Project on Death and Dead Bodies, last conference: "Death and Dissection" July 2009, Berlin, Germany

- Evolutionary Biology Digital Dissection Collections Dissection photographs for study and teaching from the University at Buffalo

- The Free Dictionary

Dissection

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Scope

Core Principles and Techniques

Anatomical dissection relies on systematic incision and separation of tissues to expose internal structures for direct observation and study, enabling precise mapping of anatomical relationships that underpin physiological function.[11] This process adheres to principles of minimal tissue trauma, proceeding layer by layer from superficial to deep to preserve integrity of underlying elements, as excessive force or improper cuts can distort or destroy delicate features like nerves and vessels.[12] Orientation and positional anatomy must guide cuts, typically starting with standardized incisions such as the midline Y-shaped pattern in human cadavers to access thoracic and abdominal cavities without compromising key landmarks. Core techniques emphasize the use of specialized instruments: scalpels for initial sharp incisions through skin and fascia, forceps for grasping and retracting tissues, dissecting scissors for curved or straight cuts in confined spaces, and probes for gentle exploration without laceration.[13] Blunt dissection, employing fingers or tools to separate natural tissue planes, complements sharp methods to reduce hemorrhage risk and maintain vascular integrity in preserved specimens.[12] Specimens are prepared via fixation in preservatives like 10% formalin to inhibit decay and firm tissues, followed by positioning on trays or tables with pins for stability during prolonged sessions. Safety protocols form an integral principle, mandating personal protective equipment including gloves, lab coats, and eye protection to mitigate biohazards from pathogens or fixatives, with immediate handwashing post-handling and proper sharps disposal to prevent injuries. [14] Instruments must be cleaned and stored dry after use, while excess fluids are wiped from surfaces to maintain a sterile field, underscoring the causal link between procedural hygiene and reduced infection transmission in laboratory settings.[15] Post-dissection, ethical disposal of remains adheres to regulations ensuring dignified handling, reflecting the balance between educational utility and respect for biological material.[16]Distinctions from Related Practices

Dissection, in the context of anatomical study, involves the systematic separation and exposure of tissues and organs in deceased specimens to elucidate normal structural relationships, primarily for educational or research purposes. This differs from autopsy, which is a specialized post-mortem examination focused on identifying pathological changes or causes of death, often prioritizing forensic or clinical diagnostic outcomes over comprehensive anatomical mapping. While both may employ similar incisions, such as thoracotomy, the intent of dissection emphasizes pedagogical demonstration of healthy morphology, whereas autopsy targets anomalies or lethal mechanisms, frequently incorporating toxicology or histology tailored to legal or medical inquiry.[17][18] Unlike vivisection, which entails surgical intervention on living organisms—typically anesthetized animals—to observe dynamic physiological processes in situ, dissection occurs exclusively on non-viable subjects, avoiding ethical and technical challenges associated with maintaining life support or minimizing suffering during exposure. Vivisection, historically employed in experiments by figures like Claude Bernard in the 19th century, seeks insights into function and response, such as blood flow or neural activity, rendering it distinct from the static, preservative-based analysis of dissection.[19] Surgical procedures, conducted on living patients, aim at therapeutic correction of pathology—such as excision of tumors or repair of trauma—prioritizing functional restoration and patient survival over detailed structural documentation. In contrast, dissection permits unhurried, repetitive exploration without concern for homeostasis, facilitating the identification of variant anatomies across populations, a process incompatible with operative constraints like bleeding control or infection risk. Gross dissection in surgical pathology, involving specimen processing for microscopic analysis, shares procedural elements but serves diagnostic rather than holistic anatomical instruction.[20] Dissection also contrasts with evisceration or butchery, which involve organ removal primarily for disposal, food preparation, or ritual without methodical layering to reveal interconnections. Evisceration, as in certain autopsy variants like the Virchow method, extracts viscera en bloc for subsequent examination, but lacks the layered, expository precision of dissection intended to preserve contextual relationships for teaching. Butchery, evident in slaughterhouse practices since antiquity, fragments tissues for utilitarian ends, eschewing the scientific scrutiny of dissection.[21][22]Types of Dissection

Human Anatomical Dissection

Human anatomical dissection entails the methodical incision and separation of preserved human cadaver tissues to expose and study internal structures, organs, and their spatial relationships.[11] This practice serves primarily as a cornerstone of gross anatomy education in medical, dental, and allied health programs, enabling learners to develop three-dimensional comprehension of human morphology beyond what models or digital simulations provide.[23] Cadavers, sourced through voluntary donation programs governed by laws such as the Uniform Anatomical Gift Act in the United States, are embalmed typically with formalin-based solutions to retard decomposition and facilitate prolonged study.[24] In educational settings, dissection proceeds layer by layer, beginning with skin and subcutaneous tissues, progressing to muscles, vessels, nerves, and viscera, guided by standardized protocols to ensure systematic exploration.[25] Techniques include sharp dissection with scalpels and scissors for precise cuts, blunt dissection using probes or fingers to separate planes without damage, and retraction to maintain visibility.[26] Groups of students, often 4-8 per cadaver, collaborate over semesters, with prosections—pre-dissected specimens—supplementing to demonstrate complex regions like the axilla or pelvis.[27] This hands-on approach fosters not only anatomical knowledge but also manual dexterity and respect for human variation, including pathological findings such as tumors or congenital anomalies observable in real tissues.[28] Empirical studies affirm dissection's efficacy; for instance, participants report superior retention and spatial awareness compared to lecture-based or virtual methods, with examination scores improving post-dissection.[25] [26] Despite alternatives like 3D printing or augmented reality gaining traction amid cadaver shortages—exacerbated by declining donation rates in some regions—dissection remains the gold standard, integrated in over 90% of U.S. medical schools as of 2024, underscoring its irreplaceable role in bridging didactic learning with clinical application.[29] [23] Regulations mandate ethical handling, including donor consent verification, biosafety protocols to mitigate formalin exposure risks for dissectors, and respectful disposition via cremation post-use.[16]Autopsy and Forensic Necropsy

An autopsy is a postmortem examination of a human body, involving systematic dissection to determine the cause, manner, and circumstances of death, often including external inspection, internal organ removal, and histopathological analysis.[30] Performed by board-certified pathologists, the procedure typically follows standardized protocols such as those outlined by the National Association of Medical Examiners, encompassing incision of the torso (Y-incision), evisceration, and organ weighing to identify pathologies like trauma, disease, or toxins.[31] In clinical settings, autopsies confirm premortem diagnoses and contribute to medical education, with historical data showing rates declining from over 50% in the mid-20th century to under 5% by 2010 in the United States due to advanced imaging alternatives, though they remain essential for unresolved cases.[32] Forensic autopsies, a subset conducted for medicolegal purposes, emphasize evidence preservation in suspicious, unnatural, or violent deaths, such as homicides or accidents, where findings like gunshot wounds or asphyxiation patterns inform criminal investigations.[30] These examinations integrate toxicology, radiology, and entomology, with pathologists documenting chain-of-custody for specimens to withstand legal scrutiny; for instance, U.S. state medical examiner offices handle over 500,000 such cases annually, prioritizing objectivity amid potential institutional pressures. Unlike hospital autopsies, forensic ones require legal authorization and avoid embalming to prevent artifactual changes, ensuring causal accuracy in court.[33] Forensic necropsy applies analogous principles to non-human animals, involving detailed postmortem dissection by veterinary pathologists to gather evidence for legal matters like animal cruelty, wildlife poaching, or neglect prosecutions.[34] The process mirrors human autopsy techniques—external exam, incision, organ dissection, and sample collection—but adapts to species-specific anatomy, such as avian skeletal structures or equine gastrointestinal tracts, with emphasis on documenting injuries like blunt force trauma or starvation.[35] In veterinary forensics, necropsies support cases under laws like the U.S. Animal Welfare Act, where findings have substantiated over 10,000 cruelty convictions since 2010, highlighting patterns of abuse often linked to human violence predictors.[36] While "autopsy" conventionally denotes human examinations and "necropsy" animal ones, the terms overlap in describing dissection-based postmortem analysis, with forensic variants distinguished by evidentiary rigor over diagnostic focus.[37] Both prioritize minimizing decomposition effects, using refrigeration and rapid processing—ideally within 24-48 hours—to preserve tissue integrity, though forensic contexts demand additional photography and measurement for reproducibility.[38] Challenges include inter-pathologist variability in interpretations, underscoring the need for peer-reviewed protocols to counter subjective biases in reporting.[39]Animal and Comparative Dissection

Animal dissection entails the methodical incision and exploration of non-human animal cadavers to reveal internal morphology, serving educational and scientific objectives. In biology curricula, it facilitates direct observation of organ systems, vascular networks, and tissue textures, offering tactile insights unattainable through simulations alone.[40] Specimens such as frogs, earthworms, perch fish, fetal pigs, and cats predominate in laboratory settings due to their affordability, preservative compatibility, and representation of invertebrate and vertebrate diversity.[41] Annually, millions of such animals undergo dissection globally, underscoring its persistence as a core pedagogical tool despite alternatives.[42] Comparative dissection amplifies this by juxtaposing anatomical features across taxa to discern homologies indicative of shared ancestry and adaptations driven by selective pressures. Laboratory protocols often sequence dissections of dogfish sharks, mudpuppies or frogs, lizards or snakes, pigeons, and quadrupedal mammals to trace evolutionary transitions in traits like limb girdles, neural architecture, and circulatory patterns.[43] [44] Such analyses reveal, for example, the persistence of aortic arches from fish to mammals, evidencing descent with modification rather than independent origins.[45] Historically, animal dissection underpinned comparative anatomy's foundations, with Aristotle's examinations of over 500 species in the 4th century BCE establishing principles of structural variation and function.[46] This tradition persisted through Galen’s porcine models in the 2nd century CE and informed 18th-century systematists like Cuvier, who correlated fossil and extant forms via dissected homologies.[47] In contemporary research, it supports phylogenetic inference and biomedical modeling, as interspecies dissections elucidate physiological divergences exploitable for zoonotic disease studies or prosthetic design.[48] Techniques emphasize precision to preserve relational integrity, employing scalpels for incisions, probes for separations, and pins for specimen stabilization on dissection trays.[49] Preservation via formalin immersion maintains structural fidelity, though ethical sourcing from licensed suppliers mitigates wild capture impacts.[50] Comparative protocols quantify metrics like organ mass ratios or bone lengths to test hypotheses on allometric scaling and ecological niches, yielding data robust against interpretive bias.[51]Historical Evolution

Ancient Origins in Classical Antiquity and India

![Galen, Opera omnia, dissection of a pig. Wellcome L0020565.jpg][float-right] In ancient Greece, systematic human dissection emerged in the Hellenistic period at the medical school of Alexandria, founded under Ptolemaic rule. Herophilus of Chalcedon (c. 335–280 BCE), often regarded as the father of anatomy, conducted the first known public dissections of human cadavers, reportedly examining several hundred bodies and distinguishing structures such as the brain's ventricles, nerves, and reproductive organs with unprecedented detail.[52] His contemporary Erasistratus of Chios (c. 304–250 BCE) complemented these efforts by dissecting human and animal specimens to explore physiological functions, including the cardiovascular and nervous systems, though human vivisections—allegedly performed on condemned criminals—ceased after their era due to renewed ethical prohibitions.[53] Prior to Alexandria, figures like Hippocrates (c. 460–377 BCE) relied primarily on clinical observation and animal analogies, as cultural taboos against disturbing human remains limited direct anatomical inquiry.[3] In the Roman Empire, dissection practices shifted toward animals owing to persistent bans on human cadavers. Galen of Pergamon (129–c. 216 CE), the preeminent physician to emperors, performed extensive vivisections and postmortem examinations on species including Barbary macaques, pigs, and dogs to infer human anatomy, documenting over 500 treatises on topics from skeletal structure to neural pathways.[54] His reliance on comparative anatomy yielded accurate descriptions of many systems but introduced errors, such as overstating the role of perforations in the heart's interventricular septum, which persisted in medical doctrine for centuries due to the authority of his empirical yet species-limited observations.[55] Parallel developments occurred in ancient India, where the Sushruta Samhita, attributed to the surgeon Sushruta (c. 6th century BCE), mandated cadaveric dissection as essential preparation for surgical training. Aspiring physicians were instructed to exhume and systematically dissect human bodies—preserved in water or on anthills—to study gross anatomy, including muscles, vessels, and organs, alongside animal and botanical equivalents for comprehensive understanding.[56] This pragmatic approach, integrated with surgical techniques like rhinoplasty and cataract removal, underscored dissection's role in advancing procedural precision, predating similar emphases in Western traditions and reflecting a cultural acceptance of anatomical exploration for therapeutic ends.[57]Medieval Advances in Islamic and Tibetan Contexts

During the Islamic Golden Age (roughly 8th to 13th centuries CE), scholars in regions spanning the Abbasid Caliphate advanced anatomical knowledge primarily through translations of Greek texts like those of Galen and Hippocrates, combined with surgical observations and limited empirical methods, though systematic human dissection remained constrained by religious prohibitions against postmortem mutilation of the body.[58] Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi (c. 936–1013 CE), in his 30-volume Kitab al-Tasrif, emphasized the necessity of anatomical understanding for surgical precision, describing over 200 instruments including scalpels, forceps, and retractors for procedures involving tissues and organs, and illustrated techniques for cauterization and wound management that implied familiarity with internal structures from animal vivisections or accidental exposures during surgery.[59] However, al-Zahrawi did not document personal dissections, relying instead on observational anatomy to critique and refine prior errors, such as Galen's misconceptions about certain vessels.[60] Ibn al-Nafis (1213–1288 CE), a Syrian physician, made a pivotal correction to Galenic theory in his Commentary on Anatomy in Avicenna's Canon (written c. 1242 CE), accurately describing pulmonary circulation: blood passes from the right ventricle to the lungs via the pulmonary artery, is refined there, and returns to the left ventricle through the pulmonary vein, explicitly rejecting invisible septal pores based on "dissection" evidence that confirmed the interventricular septum's solidity.[61] While Ibn al-Nafis referenced dissection—likely of animal hearts and possibly the human brain, as he noted the brain's vascular supply and meninges—historical accounts debate the extent of human cadaveric work due to Islamic legal norms prioritizing bodily integrity for burial, suggesting inferences from animal models or rare opportunistic examinations.[62] These contributions preserved and incrementally improved classical anatomy, influencing later European scholars via translations, but lacked the routine human dissections that characterized Renaissance Europe.[58] In medieval Tibetan contexts (7th–15th centuries CE), anatomical knowledge developed within the framework of Sowa Rigpa (Tibetan medicine), formalized in the Four Tantras (rGyud-bzhi, attributed to 8th-century synthesis but compiled later), which detailed the body's three humors (rlung, mkhris-pa, bad-kan), pulse diagnosis, and organ systems including channels (tsa), winds, and drops, derived from Indian Ayurvedic roots, Buddhist philosophy, and empirical observation rather than dissection.[63] Texts described visceral arrangements, such as the heart's position and vascular networks, through diagrammatic representations and tantric meditative visualizations of subtle anatomy, enabling therapeutic interventions like moxibustion and herbal remedies without reliance on invasive postmortem analysis.[64] No historical records confirm systematic dissection practices, as Tibetan traditions favored noninvasive diagnostics—pulse reading, urine analysis, and astrology—over cutting into cadavers, which conflicted with Buddhist reverence for the body as a vessel for enlightenment; anatomical accuracy stemmed from clinical correlations and inherited Indic models, with pictorial thangkas emerging later (17th century) to visualize these concepts for training.[65] This approach yielded practical medical efficacy, as evidenced by enduring pharmacopeias, but prioritized holistic causation over mechanistic dissection-driven empiricism.[66]Renaissance to Enlightenment in Europe

The Renaissance marked a revival of anatomical dissection in Europe, shifting from reliance on ancient texts to empirical observation of human cadavers, primarily in Italian universities such as Bologna and Padua.[4] This period saw anatomists like Andreas Vesalius (1514–1564) challenge Galenic doctrines, which were based largely on animal dissections, by conducting direct human cadaver examinations.[67] Vesalius, appointed professor at the University of Padua in 1537, emphasized hands-on dissection by both instructors and students, correcting numerous inaccuracies in prior works through meticulous layer-by-layer dissections.[68] His seminal 1543 publication, De humani corporis fabrica, illustrated precise dissections with detailed woodcuts, disseminating anatomical knowledge via the printing press and establishing a foundation for modern anatomy.[69] Dissections during this era often occurred in temporary settings within universities, with public demonstrations attracting scholars and artists, fostering interdisciplinary insights into human structure.[70] The construction of permanent anatomical theaters facilitated structured teaching; the first, at the University of Padua, was inaugurated in 1595 under Girolamo Fabrici d'Acquapendente, allowing tiered viewing of dissections for larger audiences.[71] Similar facilities emerged elsewhere, such as in Leiden around 1610, promoting comparative studies between human and animal specimens to highlight anatomical differences. Cadavers were sourced mainly from executed criminals, though shortages persisted, limiting frequency to one or two per academic year in many institutions.[3] Transitioning into the Enlightenment (roughly 1685–1815), dissection practices became more systematic and integrated into medical curricula across Europe, emphasizing observation and experimentation to advance physiology and surgery.[72] Figures like William Harvey (1578–1657) built on Renaissance methods, using vivisections and postmortem exams to elucidate blood circulation in 1628, influencing subsequent generations.[73] In the 18th century, anatomists refined techniques, including vessel injections with colored waxes to visualize circulatory systems, and expanded studies to include embryology and pathology.[74] Institutions in France and Britain increasingly relied on hospital-supplied bodies alongside criminals, though ethical tensions arose from irregular sourcing, prefiguring later reforms.[72] Innovations like Anna Morandi's (1713–1775) detailed wax anatomical models in Bologna complemented cadaver work, enabling repeated study without decay. By the late 18th century, dissection had solidified as a cornerstone of empirical science, underpinning surgical advancements and challenging humoral theories through verifiable evidence.[75]Industrial Era Developments in Britain and the United States

In Britain, the expansion of medical education during the late 18th and early 19th centuries, driven by Enlightenment influences and the need for skilled surgeons amid industrial urbanization, intensified demand for cadavers for dissection. Prior to 1832, the only legal source was bodies of executed criminals, limited to about 50-60 annually despite dozens of anatomy schools requiring hundreds.[76] This scarcity fueled widespread body snatching, with resurrectionists exhuming fresh graves from cemeteries, often targeting the poor or unmarked plots, and selling bodies for £4-£16 each to anatomists.[76] High-profile scandals, such as the 1828 Burke and Hare murders in Edinburgh—where 16 victims were killed and sold to Dr. Robert Knox—exposed the ethical perils and prompted public outrage, culminating in the Anatomy Act of 1832.[77] The Anatomy Act 1832 legalized the use of unclaimed bodies from workhouses, hospitals, and prisons for anatomical study, establishing inspectors to regulate distribution and aiming to end illicit trade.[78] It increased cadaver supply to over 600 in the first year, enabling systematic dissection in medical curricula and advancing surgical knowledge, though critics noted it disproportionately affected the impoverished by incentivizing neglect of paupers' burials.[79] By the mid-19th century, this reform professionalized anatomy teaching in institutions like University College London and King's College, integrating dissection as a core component of physician training amid Britain's industrial medical demands.[76] In the United States, parallel pressures from proliferating medical schools—rising from seven in 1800 to over 20 by 1820—created acute cadaver shortages, as legal supplies were similarly restricted to executed felons, yielding fewer than 10 bodies yearly per state.[80] Students and professors resorted to grave robbing, often from Black or pauper cemeteries, with "resurrection men" charging $10-20 per body; this practice sparked anatomy riots, such as the 1788 New York event killing medical students and the 1878 Philadelphia disturbances protesting desecration of African American graves.[81] At least 17 such riots occurred between 1765 and 1854, reflecting public fury over class and racial targeting in cadaver procurement.[81] Reform followed Britain's model, with states enacting anatomy acts: Massachusetts in 1831 permitted unclaimed bodies for dissection, followed by New York in 1854 and others by century's end, formalizing supply from public institutions and reducing but not eliminating grave robbing.[82] These laws supported the integration of hands-on dissection into curricula at schools like the University of Pennsylvania and Harvard, where by the 1840s, students dissected multiple cadavers per term, correlating with improved surgical outcomes during the Civil War era.[83] However, persistent ethical issues, including the exploitation of marginalized groups, underscored tensions between scientific progress and social equity in American medical education.[84]Sourcing and Ethical Frameworks

Historical Acquisition Methods

In ancient Greece and Ptolemaic Egypt, the earliest recorded human dissections around the 3rd century BCE by Herophilus of Chalcedon and Erasistratus of Chios relied on bodies likely obtained from condemned criminals or unclaimed deceased individuals, as systematic acquisition was not formalized and cultural taboos limited access.[3] [85] Dissection practices in classical antiquity often prioritized animal subjects due to religious and societal prohibitions against disturbing human remains, with figures like Galen in Rome (2nd century CE) primarily using pigs, apes, and other animals sourced from markets or hunts.[67] Human cadaver use remained sporadic and ethically contested until the Renaissance. During the medieval period in the Islamic world, anatomists such as Ibn Sina (Avicenna) may have conducted limited human dissections using bodies from natural deaths or executions, though textual evidence suggests reliance on animal models and observational anatomy prevailed due to Islamic legal interpretations prohibiting desecration of graves.[86] In India and China, ancient traditions referenced dissection in medical texts, with cadavers possibly acquired from unclaimed bodies or war dead, but practical implementation was rare and overshadowed by humoral theories that did not necessitate routine autopsy.[4] European medieval practices mirrored this restraint, confining legal human supplies to executed felons under church oversight, which severely restricted anatomical progress.[76] The Renaissance and early modern era in Europe saw increased demand outstripping the supply of legally executed criminals, prompting anatomists like Leonardo da Vinci in the late 15th century to employ grave robbers for clandestine acquisitions.[87] By the 18th century, "resurrectionists" or body snatchers emerged as organized networks in Britain and America, exhuming freshly buried corpses from graveyards—often of the poor—and selling them to medical schools for £4 to £16 per body, fueling scandals like the 1788 Doctors' Riot in New York over perceived thefts from potter's fields.[88] [89] Extreme cases included the 1828 Burke and Hare murders in Edinburgh, where 16 victims were killed to supply "fresh" cadavers, exposing the ethical perils and leading to the British Anatomy Act of 1832, which legalized unclaimed pauper bodies for dissection to curb illegal trade.[90] [91] Similar practices persisted in the United States until state laws in the mid-19th century mirrored Britain's reforms, shifting acquisition toward institutionalized poor relief systems.[92]Modern Legal and Donation Systems

In the United States, the Uniform Anatomical Gift Act (UAGA), first enacted in 1968 and revised in 2006, provides the primary legal framework for whole-body donation to anatomical programs for medical education and research, including dissection.[93] The UAGA permits competent adults to document consent for post-mortem donation via driver's licenses, state registries, or written forms, superseding family objections in cases of prior donor registration, though programs often consult next of kin to honor potential dissent.[94] All 50 states and the District of Columbia have adopted versions of the UAGA, standardizing processes while allowing state-specific variations, such as Michigan's Public Act 368 of 1978 authorizing bequests to medical institutions.[95] Donation programs must ensure bodies are used solely for transplantation, therapy, research, or education, with ethical guidelines from bodies like the American Association for Anatomy emphasizing donor dignity, traceability, and final disposition such as cremation and return of remains.[96] In the United Kingdom, the Human Tissue Act 2004 mandates explicit written consent for body donation to science, prohibiting use without it and requiring licensed establishments like universities to obtain approval from the Human Tissue Authority.[97] Consent can be given by the individual during life or, post-mortem, by designated relatives in a hierarchy, but anatomical examination for education demands prior donor authorization to align with public trust principles post-scandals like Alder Hey in 1999.[98] Devolved nations vary slightly; for instance, Wales under the Human Transplantation (Wales) Act 2013 introduced soft opt-out for organs in 2015 but retains opt-in for whole-body anatomical gifts.[99] Across the European Union, national laws govern donation without a unified directive for anatomical purposes, leading to diverse consent models: opt-in systems predominate, as in Denmark's Health Act of 2010 allowing bequests from those over 17, while countries like Italy's 2023 reforms enforce strict informed consent and prohibit commercial use.[100][101] In contrast, some nations such as South Africa permit limited use of unclaimed bodies under the National Health Act 2003 if claimed within 30 days, though voluntary donation is increasingly prioritized globally to address ethical concerns and shortages.[102] Internationally, frameworks emphasize autonomy and non-commercialization; for example, Australia's state-based laws require witnessed donor forms, and India's Anatomy Act amendments since 2010 promote registered voluntary programs amid past reliance on unclaimed indigents.[103] These systems reflect a post-20th-century consensus on informed consent as ethically foundational, reducing reliance on coercive historical methods while facing ongoing challenges like donor shortages prompting inter-institutional sharing or imports under strict protocols.[104]Religious, Cultural, and Philosophical Objections

In Judaism, postmortem dissection is generally prohibited as a form of desecration of the sacred human body, which must remain intact for burial to honor the deceased and facilitate resurrection; exceptions are permitted only if the procedure could directly save another life or fulfill legal mandates.[105][106] Orthodox Jewish communities have historically resisted autopsies and dissections, viewing them as violations of the principle of nivul ha'met (mutilation of the dead), though rabbinic opinions since the 20th century have occasionally condoned limited examinations for forensic or epidemiological necessity.[107] Islamic teachings emphasize rapid burial of the intact body as an act of dignity, leading to widespread objections to dissection unless required by law or to determine cause of death, with scholars like those in the Hanafi school permitting it under strict duress but prohibiting non-essential mutilation to preserve the body's purity for judgment in the afterlife.[108][107] In contrast, Christianity lacks a doctrinal ban on dissection; claims of medieval Catholic prohibitions are historically inaccurate, as papal bulls like Detestande feritatis (1299) targeted unauthorized grave-robbing rather than the practice itself, and dissections occurred in Christian Europe from the 13th century onward under ecclesiastical oversight.[109][110] Hinduism and Buddhism present varied stances influenced by karmic and reincarnation beliefs, where the body is transient but dissection may disrupt the soul's departure or ritual purity; Hindu texts do not explicitly forbid it for alleviating suffering, yet cultural practices in India have delayed widespread body donation until recent reforms, with only 0.02% of deaths leading to anatomical gifts as of 2020 due to taboos against fragmentation.[111][112] In Buddhism, autopsy or dissection is allowable once the consciousness has fully departed, as determined by a teacher, prioritizing compassion over bodily integrity.[113] Culturally, objections often intersect with religious norms but extend to indigenous and ethnic groups; Hmong communities in the United States, for instance, view autopsy as trapping the soul and preventing ancestral rituals, prompting legal exemptions in states like Wisconsin as of 2012.[114] Similarly, some African and Asian societies maintain taboos rooted in ancestor veneration, where body alteration impedes spiritual transitions, though empirical surveys indicate most cultures permit dissection when justified by public health needs, with opposition rates below 20% in diverse global samples.[115][116] Philosophically, objections to animal dissection invoke arguments from moral status, contending that vertebrates possess sentience warranting avoidance of exploitation even postmortem, as procurement often involves killing; utilitarian frameworks, as articulated by Peter Singer since 1975, prioritize minimizing harm when viable alternatives like simulations exist, citing studies showing equivalent learning outcomes without ethical costs.[117][118] For human dissection, Kantian deontology critiques historical sourcing via grave-robbing or unclaimed bodies as violations of autonomy and dignity, though proponents counter that consented donation aligns with categorical imperatives by advancing knowledge for societal benefit.[10] These views have fueled opt-out policies in education, with surveys of U.S. students revealing 20-30% ethical discomfort, often leading to alternative accommodations.[119]Applications in Education and Research

Role in Medical and Surgical Training