Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Debridement

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2013) |

| Debridement | |

|---|---|

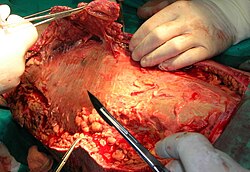

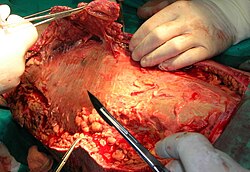

Necrotic tissue from the left leg is being surgically debrided in a patient with necrotizing fasciitis. | |

| Pronunciation | /dɪˈbriːdmənt/[1] |

| ICD-10-PCS | 0?D |

| MeSH | D003646 |

Debridement is the medical removal of dead, damaged, or infected tissue to improve the healing potential of the remaining healthy tissue.[2][3] Removal may be surgical, mechanical, chemical, autolytic (self-digestion), or by maggot therapy.

In podiatry, practitioners such as chiropodists, podiatrists and foot health practitioners remove conditions such as calluses and verrucas.

Debridement is an important part of the healing process for burns and other serious wounds; it is also used for treating some kinds of snake and spider bites.

Sometimes the boundaries of the problem tissue may not be clearly defined. For example, when excising a tumor, there may be micrometastases along the edges of the tumor that are too small to be detected, but if not removed, could cause a relapse. In such circumstances, a surgeon may opt to debride a portion of the surrounding healthy tissue to ensure that the tumor is completely removed.

Types

[edit]There is a lack of high-quality evidence to compare the effectiveness of various debridement methods on time taken for debridement or time taken for complete healing of wounds.[4]

Surgical debridement

[edit]Surgical or "sharp" debridement and laser debridement under anesthesia are the fastest methods of debridement. They are very selective, meaning that the person performing the debridement has nearly complete control over which tissue is removed and which is left behind. Surgical debridement can be performed in the operating room or bedside, depending on the extent of the necrotic material and a patient's ability to tolerate the procedure. The surgeon will typically debride tissue back to viability, as determined by tissue appearance and the presence of blood flow in healthy tissue.[5]

Autolytic debridement

[edit]Autolysis uses the body's own enzymes and moisture to re-hydrate, soften and finally liquefy hard eschar and slough. Autolytic debridement is selective; only necrotic tissue is liquefied. It is also virtually painless for the patient. Autolytic debridement can be achieved with the use of occlusive or semi-occlusive dressings which maintain wound fluid in contact with the necrotic tissue. Autolytic debridement can be achieved with hydrocolloids, hydrogels and transparent films. It is suitable for wounds where the amount of dead tissue is not extensive and where there is no infection.[6]

Enzymatic debridement

[edit]Chemical enzymes are fast-acting products that slough off necrotic tissue. These enzymes are derived from micro-organisms including Clostridium histolyticum; or from plants, examples include collagenase, varidase, papain, and bromelain. Some of these enzymatic debriders are selective, while some are not. This method works well on wounds (especially burns) with a large amount of necrotic debris or with eschar formation. However, the results are mixed and the effectiveness is variable. Therefore, this type of debridement is used sparingly and is not considered a standard of care for burn treatments.[7]

Mechanical debridement

[edit]When removal of tissue is necessary for the treatment of wounds, hydrotherapy which performs selective mechanical debridement can be used.[8] Examples of this include directed wound irrigation and therapeutic irrigation with suction.[8] Baths with whirlpool water flow should not be used to manage wounds because a whirlpool will not selectively target the tissue to be removed and can damage all tissue.[8] Whirlpools also create an unwanted risk of bacterial infection, can damage fragile body tissue, and in the case of treating arms and legs, bring risk of complications from edema.[8]

Hydrosurgery uses a high‐pressure, water‐based jet system to remove burnt skin. This should leave behind the unburned, healthy skin. A 2019 Cochrane systematic review aimed to find out if burns treated with hydrosurgery heal more quickly and with fewer infections than burns treated with a knife. The review authors only found one randomised controlled trial (RCT) with very low certainty evidence that investigated this. Based on this trial, they concluded that it is uncertain whether or not hydrosurgery is better than conventional surgery for early treatment of mid‐depth burns. More RCTs are needed to fully answer this question.[9]

Allowing a dressing to proceed from moist to dry, then manually removing the dressing causes a form of non-selective debridement. This method works best on wounds with moderate amounts of necrotic debris (e.g. "dead tissue").[citation needed]

Maggot therapy

[edit]In maggot therapy, a number of small maggots are introduced to a wound in order to consume necrotic tissue, and do so far more precisely than is possible in a normal surgical operation. Larvae of the green bottle fly (Lucilia sericata) are used, which primarily feed on the necrotic (dead) tissue of the living host without attacking living tissue. Maggots can debride a wound in one or two days. The maggots derive nutrients through a process known as "extracorporeal digestion" by secreting a broad spectrum of proteolytic enzymes that liquefy necrotic tissue, and absorb the semi-liquid result within a few days. In an optimum wound environment maggots molt twice, increasing in length from 1–2 mm to 8–10 mm, and in girth, within a period of 3–4 days by ingesting necrotic tissue, leaving a clean wound free of necrotic tissue when they are removed.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Merriam-Webster Dictionary". merriam-webster.com. 27 May 2024.

- ^ "debridement". merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 5 September 2013.

- ^ "Understand Debridement Before You Regret – Why you Need Debridement". HealthNmedicarE. 24 March 2018. Archived from the original on 9 April 2018. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ Smith, Fiona; Donaldson, Jayne; Brown, Tamara (7 May 2024). "Debridement for surgical wounds". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2024 (5) CD006214. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006214.pub5. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 11075122. PMID 38712723.

- ^ Hakkarainen, TW; Kopari, NM; Pham, TN; Evans, HL (August 2014). "Necrotizing soft tissue infections: review and current concepts in treatment, systems of care, and outcomes". Current Problems in Surgery. 51 (8): 344–62. doi:10.1067/j.cpsurg.2014.06.001. PMC 4199388. PMID 25069713.

- ^ Wound Healing and Management Node Group (June 2013). "Wound Management: Debridement - Autolytic" (PDF). Wound Practice and Research. 21 (2): 94–95. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 March 2017. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- ^ Langer, Vijay; Bhandari, P.S.; Rajagopalan, S.; Mukherjee, M.K. (2013). "Enzymatic debridement of large burn wounds with papain–urea: Is it safe?". Medical Journal Armed Forces India. 69 (2): 144–50. doi:10.1016/j.mjafi.2012.09.001. PMC 3862849. PMID 24600088.

- ^ a b c d "Choosing Wisely Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question" (Press release). ABIM Foundation. 4 April 2012. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- ^ Wormald, Justin CR; Wade, Ryckie G; Dunne, Jonathan A; Collins, Declan P; Jain, Abhilash (3 September 2020). "Hydrosurgical debridement versus conventional surgical debridement for acute partial-thickness burns". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (9) CD012826. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd012826.pub2. ISSN 1465-1858. PMC 8094409. PMID 32882071.

External links

[edit]- The short film A METHOD OF TEACHING COMBAT SURGERY (1958) is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive.