Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

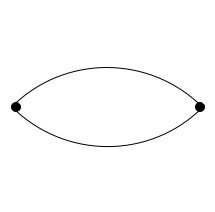

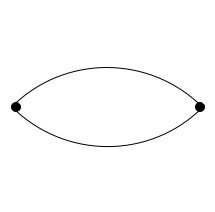

Multiple edges

View on Wikipedia

In graph theory, multiple edges (also called parallel edges or a multi-edge), are, in an undirected graph, two or more edges that are incident to the same two vertices, or in a directed graph, two or more edges with both the same tail vertex and the same head vertex. A simple graph has no multiple edges and no loops.

Depending on the context, a graph may be defined so as to either allow or disallow the presence of multiple edges (often in concert with allowing or disallowing loops):

- Where graphs are defined so as to allow multiple edges and loops, a graph without loops or multiple edges is often distinguished from other graphs by calling it a simple graph.[1]

- Where graphs are defined so as to disallow multiple edges and loops, a multigraph or a pseudograph is often defined to mean a "graph" which can have multiple edges.[2]

Multiple edges are, for example, useful in the consideration of electrical networks, from a graph theoretical point of view.[3] Additionally, they constitute the core differentiating feature of multidimensional networks.

A planar graph remains planar if an edge is added between two vertices already joined by an edge; thus, adding multiple edges preserves planarity.[4]

A dipole graph is a graph with two vertices, in which all edges are parallel to each other.

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- Balakrishnan, V. K.; Graph Theory, McGraw-Hill; 1 edition (February 1, 1997). ISBN 0-07-005489-4.

- Bollobás, Béla; Modern Graph Theory, Springer; 1st edition (August 12, 2002). ISBN 0-387-98488-7.

- Diestel, Reinhard; Graph Theory, Springer; 2nd edition (February 18, 2000). ISBN 0-387-98976-5.

- Gross, Jonathon L, and Yellen, Jay; Graph Theory and Its Applications, CRC Press (December 30, 1998). ISBN 0-8493-3982-0.

- Gross, Jonathon L, and Yellen, Jay; (eds); Handbook of Graph Theory. CRC (December 29, 2003). ISBN 1-58488-090-2.

- Zwillinger, Daniel; CRC Standard Mathematical Tables and Formulae, Chapman & Hall/CRC; 31st edition (November 27, 2002). ISBN 1-58488-291-3.