Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

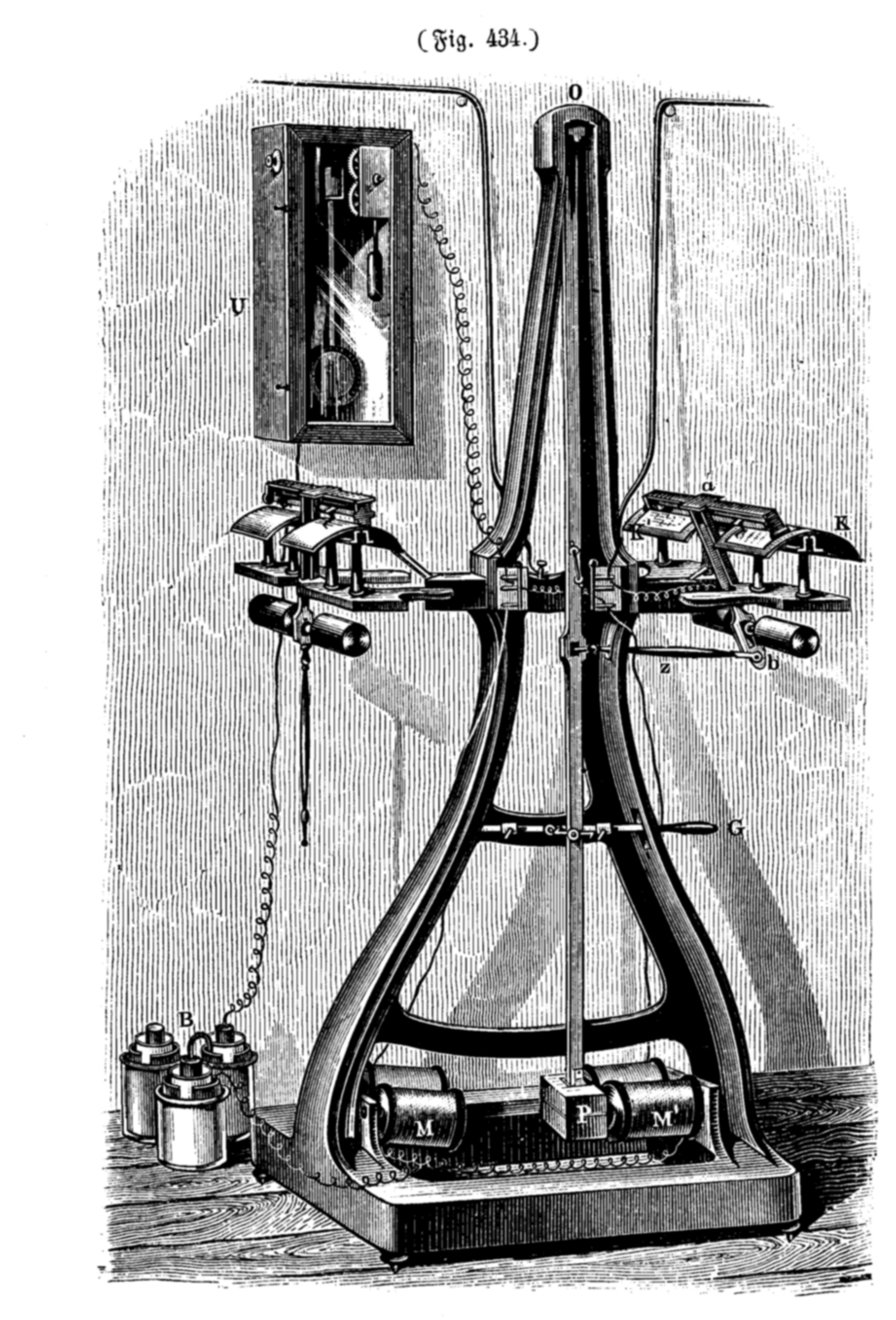

Pantelegraph

View on Wikipedia

The pantelegraph (Italian: pantelegrafo; French: pantélégraphe) was an early form of facsimile machine transmitting over normal telegraph lines developed by Giovanni Caselli, used commercially in the 1860s, that was the first such device to enter practical service. It could transmit handwriting, signatures, or drawings within an area of up to 150 mm × 100 mm (5.9 in × 3.9 in).

Description

[edit]The pantelegraph used a regulating clock with a pendulum which made and broke the current for magnetizing its regulators, and ensured that the transmitter's scanning stylus and the receiver's writing stylus remained in step. To provide a time base, a large pendulum was used weighing 8 kg (18 lb), mounted on a frame 2 m (6 ft 7 in) high. Two messages were written with insulating ink on two fixed metal plates; one plate was scanned as the pendulum moved to the right and the other as the pendulum moved to the left, so that two messages could be transmitted per cycle.[1] The receiving apparatus reproduced the transmitted image by means of paper impregnated with potassium ferricyanide, which darkened when an electric current passed through it from the synchronized stylus. In operation the pantelegraph was relatively slow; a sheet of paper 111 mm × 27 mm (4.4 in × 1.1 in), with about 25 handwritten words, took 108 seconds to transmit.[2]

The most common use of the pantelegraph was for signature verification in banking transactions.

History

[edit]

While employed teaching physics at the University of Florence, Giovanni Caselli devoted much time to research into the telegraphic transmission of images. The major problem of the time was to get perfect synchronization between the transmitting and receiving parts so they would work together correctly. Caselli developed an electrochemical technology with a "synchronizing apparatus" (regulating clock) to make the sending and receiving mechanisms work together that was far superior to any technology Bain or Bakewell had.[3]

By 1856, he had made sufficient progress for Leopold II, Grand Duke of Tuscany to take an interest in his work, and the following year he travelled to Paris where he was assisted by the engineer Paul-Gustave Froment, to whom he had been recommended by Léon Foucault, to construct the first pantelegraph. In 1858, Caselli's improved version was demonstrated by French physicist Alexandre-Edmond Becquerel at the French Academy of Sciences in Paris.[1]

On 10 May 1860 Napoleon III visited Froment's workshop to observe a demonstration of the device, and was so enthused by the device that he secured access for Caselli to the telegraph lines he needed to further his work, from Froment's workshops to the Paris Observatory. In November 1860 a telegraph line between Paris and Amiens was allotted to Caselli which enabled a true long-distance experiment, which was a complete success, with the signature of the composer Gioacchino Rossini as the image sent and received, over a distance of 140 km (87 mi).[1] The composer wrote a piece, allegretto ‘del pantelegrafo’, for piano, marking the event.

The first "pantelegram" was sent from Lyon to Paris on 10 February 1862. The Corps législatif later ordered the installation of the pantelegraph on the railway line between the two cities, and from February 1863 the public was able to use it. French law was enacted in 1864 for the pantelegraph facsimile system to be officially accepted. The next year in 1865 the operations started with the Paris to Lyon line and extended to Marseille in 1867.[4]

Russian Tsar Alexander II installed an experimental service between his palaces in Saint Petersburg and Moscow between 1864 and 1865.[1][4][5] In 1867 the Director of Telegraphs of France, de Vougy, had a second line set up from Lyon to Marseille; the transmission cost was 20 centimes per square centimetre of image, and the service was operated until 1870.[6]

Surviving machines

[edit]There are few remaining examples of the original pantelegraph. A formidable display of the pantelegraph was mounted in 1961 at the Musée National des Techniques, when a centennial celebration of the device was performed between Paris and Marseille. Again in 1982 their reliability was displayed; at the Postal Museum in Riquewihr, two pantelegraphs were used for six hours a day, for several months, performing without error.

An original specimen is also kept on display at the Istituto Della Porta in Naples.[7]

One pantelegraph is in Munich (German Museum); it was (as of 2007) never displayed.[8]

Another specimen is displayed at the A.S. Popov Central Museum of Communications in St Petersburg, Russia.[9]

Literature

[edit]- Zons, Julia (2015). Casellis Pantelegraph: Geschichte eines vergessenen Mediums (PhD). Universität Konstanz. ISBN 978-3-8394-3116-0. 31792.

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ a b c d Huurdeman 2003, pp. 149–150

- ^ Sabine, Robert (1869). The History and Progress of the Electric Telegraph. Virtue & Co. p. 206.

- ^ Mid Nineteenth Century Electrochemistry

- ^ a b Huurdeman 2003, p. 150 This test was also successful, so that the pantelegraph became accepted for use on the French telegraph network by law on April 24, 1864. Official operation started on the Paris-Lyon line on February 16, 1865 and was extended to Marseille in 1867.

- ^ Huurdeman 2003, p. 150 The pantelegraph was also introduced in England on a line between London and Liverpool in 1863...One year later Tsar Nicholas 1 used the pantelegraph between his palaces in St.Petersburg and Moscow.

- ^ Burns, R.W. (2004). Communications: an International History of the Formative Years. IET. pp. 213–4. ISBN 978-0-86341-327-8.

- ^ Istituto Tecnico Statale "Gian Battista Della Porta - Porzio" Napoli

- ^ Zons 2015, p. 7

- ^ State Catalogue of the Museum Fund of Russia

References

[edit]- Anzovin, Steven; et al. (2000). Famous first facts, international edition: a record of first happenings, discoveries, and inventions in world history. H. W. Wilson. ISBN 0-8242-0958-3.

- Huurdeman, Anton A. (2003). The worldwide history of telecommunications. Wiley-IEEE. ISBN 0-471-20505-2.

- Sarkar, Tapan K.; et al. (2006). History of wireless. Wiley. ISBN 0-471-71814-9.

External links

[edit]- Giovanni Caselli, by Eugenii Katz. Internet Archive version.

- Pantelegraph

- Facsimile & SSTV History — this site has many images

- History of The Pantelegraph — Information and More Pictures on the Pantelegraph

- Giovanni Caselli and the Pantelegraph — Biographical and Historical Account of the Pantelegraph