Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Pinnation

View on Wikipedia

Pinnation (also called pennation) is the arrangement of feather-like or multi-divided features arising from both sides of a common axis. Pinnation occurs in biological morphology, in crystals,[1] such as some forms of ice or metal crystals,[2][3] and in patterns of erosion or stream beds.[4]

The term derives from the Latin word pinna meaning "feather", "wing", or "fin". A similar concept is "pectination", which is a comb-like arrangement of parts (arising from one side of an axis only). Pinnation is commonly referred to in contrast to "palmation", in which the parts or structures radiate out from a common point. The terms "pinnation" and "pennation" are cognate, and although they are sometimes used distinctly, there is no consistent difference in the meaning or usage of the two words.[5][6]

Plants

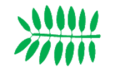

[edit]Botanically, pinnation is an arrangement of discrete structures (such as leaflets, veins, lobes, branches, or appendages) arising at multiple points along a common axis. For example, once-divided leaf blades having leaflets arranged on both sides of a rachis are pinnately compound leaves. Many palms (notably the feather palms) and most cycads and grevilleas have pinnately divided leaves. Most species of ferns have pinnate or more highly divided fronds, and in ferns, the leaflets or segments are typically referred to as "pinnae" (singular "pinna"). Plants with pinnate leaves are sometimes colloquially called "feather-leaved". Most of the following definitions are from Jackson's Glossary of Botanical Terms:[6]

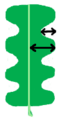

Depth of divisions

[edit]- pinnatifid and pinnatipartite: leaves with pinnate lobes that are not discrete, remaining sufficiently connected to each other that they are not separate leaflets.

- pinnatisect: cut all the way to the midrib or other axis, but with the bases of the pinnae not contracted to form discrete leaflets.

- pinnate-pinnatifid: pinnate, with the pinnae being pinnatifid.

-

pinnately-lobed

-

pinnately-cleft

-

pinnately-parted

-

pinnately-divided

-

pinnatisect

Number of divisions

[edit]- paripinnate: pinnately compound leaves in which leaflets are borne in pairs along the rachis without a single terminal leaflet; also called "even-pinnate".

- imparipinnate: pinnately compound leaves in which there is a lone terminal leaflet rather than a terminal pair of leaflets; also called "odd-pinnate".

-

even pinnate

-

odd pinnate

-

alternipinnate

Iteration of divisions

[edit]

- bipinnate: pinnately compound leaves in which the leaflets are themselves pinnately compound; also called "twice-pinnate".

- tripinnate: pinnately compound leaves in which the leaflets are themselves bipinnate; also called "thrice-pinnate".

- tetrapinnate: pinnately compound leaves in which the leaflets are themselves tripinnate.

- unipinnate: solitary compound leaf with a row of leaflets arranged along each side of a common rachis.

-

bipinnate

-

geminate-pinnate

-

tripinnate

The term pinnula (plural: pinnulae) is the Latin diminutive of pinna (plural: pinnae); either as such or in the Anglicised form: pinnule, it is differently defined by various authorities. Some apply it to the leaflets of a pinna, especially the leaflets of bipinnate or tripinnate leaves.[7] Others also or alternatively apply it to second or third order divisions of a bipinnate or tripinnate leaf.[8] It is the ultimate free division (or leaflet) of a compound leaf, or a pinnate subdivision of a multipinnate leaf.

Animals

[edit]In animals, pinnation occurs in various organisms and structures, including:

- Some muscles can be unipinnate or bipinnate muscles.

- The fish Platax pinnatus is known as the pinnate spadefish or pinnate batfish.

Geomorphology

[edit]Pinnation occurs in certain waterway systems in which all major tributary streams enter the main channels by flowing in one direction at an oblique angle.[9]

References

[edit]- ^ Nicholas Eastaugh, Valentine Walsh, Tracey Chaplin, Ruth Siddall. Pigment Compendium: A Dictionary of Historical Pigments. Butterworth-Heinemann 2008. ISBN 978-0-7506-8980-9.

- ^ Charles Seymour Wright, Raymond Edward Priestley. Glaciology. Harrison and Sons, for the Committee of the Captain Scott Arctic Fund. 1922.

- ^ Journal of the Electrochemical Society, Volume 100, 1953, page 165: "The zinc is recovered electrolytically as 'flake' powder consisting of pinnate crystals."

- ^ Ravi P. Gupta. Remote Sensing Geology. Springer 2003. ISBN 978-3-540-43185-5.

- ^ Collocott, T. C., ed. (1974). Chambers Dictionary of science and technology. Edinburgh: W. and R. Chambers. ISBN 0-550-13202-3.

- ^ a b Jackson, Benjamin, Daydon; A Glossary of Botanic Terms with their Derivation and Accent. Gerald Duckworth & Co. London, 4th ed 1928.

- ^ Chittenden, Fred J. Ed., Royal Horticultural Society Dictionary of Gardening. Oxford. 1951.

- ^ Shastri, Varun. Dictionary of Botany. Isha Books. 2005. ISBN 978-8182052253.

- ^ Parvis, Merle (December 1949). "DRAINAGE PATTERN SIGNIFICANCE IN AIRPHOTO IDENTIFICATION OF SOILS AND BEDROCKS*" (PDF). Joint Highway Research Project. Retrieved 18 June 2025.