Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Tendon

View on Wikipedia

| Tendon | |

|---|---|

| |

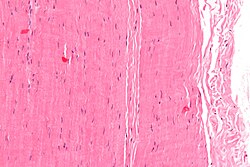

Micrograph of a piece of tendon; H&E stain | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | tendo |

| MeSH | D013710 |

| TA2 | 2010 |

| TH | H3.03.00.0.00020 |

| FMA | 9721 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

A tendon or sinew is a tough band of dense fibrous connective tissue that connects muscle to bone. It sends the mechanical forces of muscle contraction to the skeletal system, while withstanding tension.

Tendons, like ligaments, are made of collagen. The difference is that ligaments connect bone to bone, while tendons connect muscle to bone. There are about 4,000 tendons in the adult human body.[1][2]

Structure

[edit]A tendon is made of dense regular connective tissue, whose main cellular components are special fibroblasts called tendon cells (tenocytes).[3] Tendon cells synthesize the tendon's extracellular matrix, which abounds with densely-packed collagen fibers. The collagen fibers run parallel to each other and are grouped into fascicles. Each fascicle is bound by an endotendineum, which is a delicate loose connective tissue containing thin collagen fibrils[4][5] and elastic fibers.[6] A set of fascicles is bound by an epitenon, which is a sheath of dense irregular connective tissue. The whole tendon is enclosed by a fascia. The space between the fascia and the tendon tissue is filled with the paratenon, a fatty loose connective tissue.[7] Normal healthy tendons are anchored to bone by Sharpey's fibres.

Extracellular matrix

[edit]The dry mass of normal tendons, which is 30–45% of their total mass, is made of:

- 60–85% collagen

- 60–80% collagen I

- 0–10% collagen III

- 2% collagen IV

- small amounts of collagens V, VI, and others

- 15–40% non-collagenous extracellular matrix components, including:

- 3% cartilage oligomeric matrix protein,

- 1–2% elastin,

- 1–5% proteoglycans,

- 0.2% inorganic components such as copper, manganese, and calcium.[8][9][10][11]

Although most of a tendon's collagen is type I collagen, many minor collagens are present that play vital roles in tendon development and function. These include type II collagen in the cartilaginous zones, type III collagen in the reticulin fibres of the vascular walls, type IX collagen, type IV collagen in the basement membranes of the capillaries, type V collagen in the vascular walls, and type X collagen in the mineralized fibrocartilage near the interface with the bone.[8][12]

Ultrastructure and collagen synthesis

[edit]Collagen fibres coalesce into macroaggregates. After secretion from the cell, cleaved by procollagen N- and C-proteases, the tropocollagen molecules spontaneously assemble into insoluble fibrils. A collagen molecule is about 300 nm long and 1–2 nm wide, and the diameter of the fibrils that are formed can range from 50–500 nm. In tendons, the fibrils then assemble further to form fascicles, which are about 10 mm in length with a diameter of 50–300 μm, and finally into a tendon fibre with a diameter of 100–500 μm.[13]

The collagen in tendons are held together with proteoglycan (a compound consisting of a protein bonded to glycosaminoglycan groups, present especially in connective tissue) components including decorin and, in compressed regions of tendon, aggrecan, which are capable of binding to the collagen fibrils at specific locations.[14] The proteoglycans are interwoven with the collagen fibrils – their glycosaminoglycan (GAG) side chains have multiple interactions with the surface of the fibrils – showing that the proteoglycans are important structurally in the interconnection of the fibrils.[15] The major GAG components of the tendon are dermatan sulfate and chondroitin sulfate, which associate with collagen and are involved in the fibril assembly process during tendon development. Dermatan sulfate is thought to be responsible for forming associations between fibrils, while chondroitin sulfate is thought to be more involved with occupying volume between the fibrils to keep them separated and help withstand deformation.[16] The dermatan sulfate side chains of decorin aggregate in solution, and this behavior can assist with the assembly of the collagen fibrils. When decorin molecules are bound to a collagen fibril, their dermatan sulfate chains may extend and associate with other dermatan sulfate chains on decorin that is bound to separate fibrils, therefore creating interfibrillar bridges and eventually causing parallel alignment of the fibrils.[17]

Tenocytes

[edit]The tenocytes produce the collagen molecules, which aggregate end-to-end and side-to-side to produce collagen fibrils. Fibril bundles are organized to form fibres with the elongated tenocytes closely packed between them. There is a three-dimensional network of cell processes associated with collagen in the tendon. The cells communicate with each other through gap junctions, and this signalling gives them the ability to detect and respond to mechanical loading.[18] These communications happen by two proteins essentially: connexin 43, present where the cells processes meet and in cell bodies connexin 32, present only where the processes meet.[19]

Blood vessels may be visualized within the endotendon running parallel to collagen fibres, with occasional branching transverse anastomoses.

The internal tendon bulk is thought to contain no nerve fibres, but the epitenon and paratenon contain nerve endings, while Golgi tendon organs are present at the myotendinous junction between tendon and muscle.

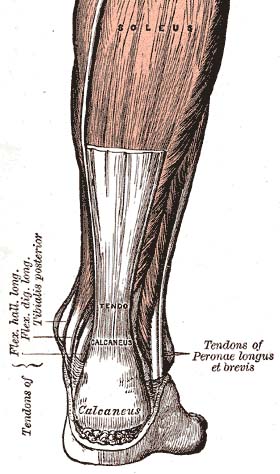

Tendon length varies in all major groups and from person to person. Tendon length is, in practice, the deciding factor regarding actual and potential muscle size. For example, all other relevant biological factors being equal, a man with a shorter tendons and a longer biceps muscle will have greater potential for muscle mass than a man with a longer tendon and a shorter muscle. Successful bodybuilders will generally have shorter tendons. Conversely, in sports requiring athletes to excel in actions such as running or jumping, it is beneficial to have longer than average Achilles tendon and a shorter calf muscle.[20]

Tendon length is determined by genetic predisposition, and has not been shown to either increase or decrease in response to environment, unlike muscles, which can be shortened by trauma, use imbalances and a lack of recovery and stretching.[21] In addition tendons allow muscles to be at an optimal distance from the site where they actively engage in movement, passing through regions where space is premium, like the carpal tunnel.[19]

List of tendons

[edit]There are about 4,000 tendons in the human body, of which 55 are listed in the following table:

Sortable table of tendons in the human body

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Naming convention for the table:

|

Functions

[edit]

Traditionally, tendons have been considered to be a mechanism by which muscles connect to bone as well as muscles itself, functioning to transmit forces. This connection allows tendons to passively modulate forces during locomotion, providing additional stability with no active work. However, over the past two decades, much research has focused on the elastic properties of some tendons and their ability to function as springs. Not all tendons are required to perform the same functional role, with some predominantly positioning limbs, such as the fingers when writing (positional tendons) and others acting as springs to make locomotion more efficient (energy storing tendons).[22] Energy storing tendons can store and recover energy at high efficiency. For example, during a human stride, the Achilles tendon stretches as the ankle joint dorsiflexes. During the last portion of the stride, as the foot plantar-flexes (pointing the toes down), the stored elastic energy is released. Furthermore, because the tendon stretches, the muscle is able to function with less or even no change in length, allowing the muscle to generate more force.

The mechanical properties of the tendon are dependent on the collagen fiber diameter and orientation. The collagen fibrils are parallel to each other and closely packed, but show a wave-like appearance due to planar undulations, or crimps, on a scale of several micrometers.[23] In tendons, the collagen fibres have some flexibility due to the absence of hydroxyproline and proline residues at specific locations in the amino acid sequence, which allows the formation of other conformations such as bends or internal loops in the triple helix and results in the development of crimps.[24] The crimps in the collagen fibrils allow the tendons to have some flexibility as well as a low compressive stiffness. In addition, because the tendon is a multi-stranded structure made up of many partially independent fibrils and fascicles, it does not behave as a single rod, and this property also contributes to its flexibility.[25]

The proteoglycan components of tendons also are important to the mechanical properties. While the collagen fibrils allow tendons to resist tensile stress, the proteoglycans allow them to resist compressive stress. These molecules are very hydrophilic, meaning that they can absorb a large amount of water and therefore have a high swelling ratio. Since they are noncovalently bound to the fibrils, they may reversibly associate and disassociate so that the bridges between fibrils can be broken and reformed. This process may be involved in allowing the fibril to elongate and decrease in diameter under tension.[26] However, the proteoglycans may also have a role in the tensile properties of tendon. The structure of tendon is effectively a fibre composite material, built as a series of hierarchical levels. At each level of the hierarchy, the collagen units are bound together by either collagen crosslinks, or the proteoglycans, to create a structure highly resistant to tensile load.[27] The elongation and the strain of the collagen fibrils alone have been shown to be much lower than the total elongation and strain of the entire tendon under the same amount of stress, demonstrating that the proteoglycan-rich matrix must also undergo deformation, and stiffening of the matrix occurs at high strain rates.[28] This deformation of the non-collagenous matrix occurs at all levels of the tendon hierarchy, and by modulating the organisation and structure of this matrix, the different mechanical properties required by different tendons can be achieved.[29] Energy storing tendons have been shown to utilise significant amounts of sliding between fascicles to enable the high strain characteristics they require, whilst positional tendons rely more heavily on sliding between collagen fibres and fibrils.[30] However, recent data suggests that energy storing tendons may also contain fascicles which are twisted, or helical, in nature - an arrangement that would be highly beneficial for providing the spring-like behaviour required in these tendons.[31]

Mechanics

[edit]Tendons are viscoelastic structures, which means they exhibit both elastic and viscous behaviour. When stretched, tendons exhibit typical "soft tissue" behavior. The force-extension, or stress-strain curve starts with a very low stiffness region, as the crimp structure straightens and the collagen fibres align suggesting negative Poisson's ratio in the fibres of the tendon. More recently, tests carried out in vivo (through MRI) and ex vivo (through mechanical testing of various cadaveric tendon tissue) have shown that healthy tendons are highly anisotropic and exhibit a negative Poisson's ratio (auxetic) in some planes when stretched up to 2% along their length, i.e. within their normal range of motion.[32] After this 'toe' region, the structure becomes significantly stiffer, and has a linear stress-strain curve until it begins to fail. The mechanical properties of tendons vary widely, as they are matched to the functional requirements of the tendon. The energy storing tendons tend to be more elastic, or less stiff, so they can more easily store energy, whilst the stiffer positional tendons tend to be a little more viscoelastic, and less elastic, so they can provide finer control of movement. A typical energy storing tendon will fail at around 12–15% strain, and a stress in the region of 100–150 MPa, although some tendons are notably more extensible than this, for example the superficial digital flexor in the horse, which stretches in excess of 20% when galloping.[33] Positional tendons can fail at strains as low as 6–8%, but can have moduli in the region of 700–1000 MPa.[34]

Several studies have demonstrated that tendons respond to changes in mechanical loading with growth and remodeling processes, much like bones. In particular, a study showed that disuse of the Achilles tendon in rats resulted in a decrease in the average thickness of the collagen fiber bundles comprising the tendon.[35] In humans, an experiment in which people were subjected to a simulated micro-gravity environment found that tendon stiffness decreased significantly, even when subjects were required to perform restiveness exercises.[36] These effects have implications in areas ranging from treatment of bedridden patients to the design of more effective exercises for astronauts.

Clinical significance

[edit]Injury

[edit]Tendons are subject to many types of injuries. There are various forms of tendinopathies or tendon injuries due to overuse. These types of injuries generally result in inflammation and degeneration or weakening of the tendons, which may eventually lead to tendon rupture.[37] Tendinopathies can be caused by a number of factors relating to the tendon extracellular matrix (ECM), and their classification has been difficult because their symptoms and histopathology often are similar.

Types of tendinopathy include:[38]

- Tendinosis: non-inflammatory injury to the tendon at the cellular level. The degradation is caused by damage to collagen, cells, and the vascular components of the tendon, and is known to lead to rupture.[39] Observations of tendons that have undergone spontaneous rupture have shown the presence of collagen fibrils that are not in the correct parallel orientation or are not uniform in length or diameter, along with rounded tenocytes, other cell abnormalities, and the ingrowth of blood vessels.[37] Other forms of tendinosis that have not led to rupture have also shown the degeneration, disorientation, and thinning of the collagen fibrils, along with an increase in the amount of glycosaminoglycans between the fibrils.[40]

- Tendinitis: degeneration with inflammation of the tendon as well as vascular disruption.[8]

- Paratenonitis: inflammation of the paratenon, or paratendinous sheet located between the tendon and its sheath.[38]

Tendinopathies may be caused by several intrinsic factors including age, body weight, and nutrition. The extrinsic factors are often related to sports and include excessive forces or loading, poor training techniques, and environmental conditions.[41]

Healing

[edit]It was believed that tendons could not undergo matrix turnover and that tenocytes were not capable of repair. However, it has since been shown that, throughout the lifetime of a person, tenocytes in the tendon actively synthesize matrix components as well as enzymes such as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) can degrade the matrix.[41] Tendons are capable of healing and recovering from injuries in a process that is controlled by the tenocytes and their surrounding extracellular matrix.

The three main stages of tendon healing are inflammation, repair or proliferation, and remodeling, which can be further divided into consolidation and maturation. These stages can overlap with each other. In the first stage, inflammatory cells such as neutrophils are recruited to the injury site, along with erythrocytes. Monocytes and macrophages are recruited within the first 24 hours, and phagocytosis of necrotic materials at the injury site occurs. After the release of vasoactive and chemotactic factors, angiogenesis and the proliferation of tenocytes are initiated. Tenocytes then move into the site and start to synthesize collagen III.[37][40] After a few days, the repair or proliferation stage begins. In this stage, the tenocytes are involved in the synthesis of large amounts of collagen and proteoglycans at the site of injury, and the levels of GAG and water are high.[42] After about six weeks, the remodeling stage begins. The first part of this stage is consolidation, which lasts from about six to ten weeks after the injury. During this time, the synthesis of collagen and GAGs is decreased, and the cellularity is also decreased as the tissue becomes more fibrous as a result of increased production of collagen I and the fibrils become aligned in the direction of mechanical stress.[40] The final maturation stage occurs after ten weeks, and during this time there is an increase in crosslinking of the collagen fibrils, which causes the tissue to become stiffer. Gradually, over about one year, the tissue will turn from fibrous to scar-like.[42]

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) have a very important role in the degradation and remodeling of the ECM during the healing process after a tendon injury. Certain MMPs including MMP-1, MMP-2, MMP-8, MMP-13, and MMP-14 have collagenase activity, meaning that, unlike many other enzymes, they are capable of degrading collagen I fibrils. The degradation of the collagen fibrils by MMP-1 along with the presence of denatured collagen are factors that are believed to cause weakening of the tendon ECM and an increase in the potential for another rupture to occur.[43] In response to repeated mechanical loading or injury, cytokines may be released by tenocytes and can induce the release of MMPs, causing degradation of the ECM and leading to recurring injury and chronic tendinopathies.[40]

A variety of other molecules are involved in tendon repair and regeneration. There are five growth factors that have been shown to be significantly upregulated and active during tendon healing: insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-I), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), and transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β).[42] These growth factors all have different roles during the healing process. IGF-1 increases collagen and proteoglycan production during the first stage of inflammation, and PDGF is also present during the early stages after injury and promotes the synthesis of other growth factors along with the synthesis of DNA and the proliferation of tendon cells.[42] The three isoforms of TGF-β (TGF-β1, TGF-β2, TGF-β3) are known to play a role in wound healing and scar formation.[44] VEGF is well known to promote angiogenesis and to induce endothelial cell proliferation and migration, and VEGF mRNA has been shown to be expressed at the site of tendon injuries along with collagen I mRNA.[45] Bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) are a subgroup of TGF-β superfamily that can induce bone and cartilage formation as well as tissue differentiation, and BMP-12 specifically has been shown to influence formation and differentiation of tendon tissue and to promote fibrogenesis.[citation needed]

Effects of activity on healing

[edit]In animal models, extensive studies have been conducted to investigate the effects of mechanical strain in the form of activity level on tendon injury and healing. While stretching can disrupt healing during the initial inflammatory phase, it has been shown that controlled movement of the tendons after about one week following an acute injury can help to promote the synthesis of collagen by the tenocytes, leading to increased tensile strength and diameter of the healed tendons and fewer adhesions than tendons that are immobilized. In chronic tendon injuries, mechanical loading has also been shown to stimulate fibroblast proliferation and collagen synthesis along with collagen realignment, all of which promote repair and remodeling.[42] To further support the theory that movement and activity assist in tendon healing, it has been shown that immobilization of the tendons after injury often has a negative effect on healing. In rabbits, collagen fascicles that are immobilized have shown decreased tensile strength, and immobilization also results in lower amounts of water, proteoglycans, and collagen crosslinks in the tendons.[37]

Several mechanotransduction mechanisms have been proposed as reasons for the response of tenocytes to mechanical force that enable them to alter their gene expression, protein synthesis, and cell phenotype, and eventually cause changes in tendon structure. A major factor is mechanical deformation of the extracellular matrix, which can affect the actin cytoskeleton and therefore affect cell shape, motility, and function. Mechanical forces can be transmitted by focal adhesion sites, integrins, and cell-cell junctions. Changes in the actin cytoskeleton can activate integrins, which mediate "outside-in" and "inside-out" signaling between the cell and the matrix. G-proteins, which induce intracellular signaling cascades, may also be important, and ion channels are activated by stretching to allow ions such as calcium, sodium, or potassium to enter the cell.[42]

Society and culture

[edit]Sinew was widely used throughout pre-industrial eras as a tough, durable fiber. Some specific uses include using sinew as thread for sewing, attaching feathers to arrows (see fletch), lashing tool blades to shafts, etc. It is also recommended in survival guides as a material from which strong cordage can be made for items like traps or living structures. Tendon must be treated in specific ways to function usefully for these purposes. Inuit and other circumpolar people utilized sinew as the only cordage for all domestic purposes due to the lack of other suitable fiber sources in their ecological habitats. The elastic properties of particular sinews were also used in composite recurved bows favoured by the steppe nomads of Eurasia, and Native Americans. The first stone throwing artillery also used the elastic properties of sinew.

Sinew makes for an excellent cordage material for three reasons: It is extremely strong, it contains natural glues, and it shrinks as it dries, doing away with the need for knots[clarification needed].

Culinary uses

[edit]Tendon (in particular, beef tendon) is used as a food in some Asian cuisines (often served at yum cha or dim sum restaurants). One popular dish is suan bao niu jin, in which the tendon is marinated in garlic. It is also sometimes found in the Vietnamese noodle dish phở.

Other animals

[edit]

In some organisms, notably birds,[46] and ornithischian dinosaurs,[47] portions of the tendon can become ossified. In this process, osteocytes infiltrate the tendon and lay down bone as they would in sesamoid bone such as the patella. In birds, tendon ossification primarily occurs in the hindlimb, while in ornithischian dinosaurs, ossified axial muscle tendons form a latticework along the neural and haemal spines on the tail, presumably for support.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Protect Your Tendons". NIH News in Health. 2017-05-15. Retrieved 2023-09-11.

- ^ "Framing Within Our Bodies". Southern Hills Hospital & Medical Center. Retrieved 2023-09-11.

- ^ Harvey T, Flamenco S, Fan CM (December 2019). "A Tppp3+Pdgfra+ tendon stem cell population contributes to regeneration and reveals a shared role for PDGF signalling in regeneration and fibrosis". Nature Cell Biology. 21 (12): 1490–1503. doi:10.1038/s41556-019-0417-z. PMC 6895435. PMID 31768046.

- ^ Dorlands Medical Dictionary, page 602

- ^ Caldini EG, Caldini N, De-Pasquale V, Strocchi R, Guizzardi S, Ruggeri A, et al. (1990). "Distribution of elastic system fibres in the rat tail tendon and its associated sheaths". Acta Anatomica. 139 (4): 341–348. doi:10.1159/000147022. PMID 1706129.

- ^ Grant TM, Thompson MS, Urban J, Yu J (June 2013). "Elastic fibres are broadly distributed in tendon and highly localized around tenocytes". Journal of Anatomy. 222 (6): 573–579. doi:10.1111/joa.12048. PMC 3666236. PMID 23587025.

- ^ Dorlands Medical Dictionary 2012.Page 1382

- ^ a b c Jozsa L, Kannus P (1997). Human Tendons: Anatomy, Physiology, and Pathology. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- ^ Lin TW, Cardenas L, Soslowsky LJ (June 2004). "Biomechanics of tendon injury and repair". Journal of Biomechanics. 37 (6): 865–877. doi:10.1016/j.jbiomech.2003.11.005. PMID 15111074.

- ^ Kjaer M (April 2004). "Role of extracellular matrix in adaptation of tendon and skeletal muscle to mechanical loading". Physiological Reviews. 84 (2): 649–698. doi:10.1152/physrev.00031.2003. PMID 15044685.

- ^ Taye N, Karoulias SZ, Hubmacher D (January 2020). "The "other" 15-40%: The Role of Non-Collagenous Extracellular Matrix Proteins and Minor Collagens in Tendon". Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 38 (1): 23–35. doi:10.1002/jor.24440. PMC 6917864. PMID 31410892.

- ^ Fukuta S, Oyama M, Kavalkovich K, Fu FH, Niyibizi C (April 1998). "Identification of types II, IX and X collagens at the insertion site of the bovine achilles tendon". Matrix Biology. 17 (1): 65–73. doi:10.1016/S0945-053X(98)90125-1. PMID 9628253.

- ^ Fratzl P (2009). "Cellulose and collagen: from fibres to tissues". Current Opinion in Colloid & Interface Science. 8 (1): 32–39. doi:10.1016/S1359-0294(03)00011-6.

- ^ Zhang G, Ezura Y, Chervoneva I, Robinson PS, Beason DP, Carine ET, et al. (August 2006). "Decorin regulates assembly of collagen fibrils and acquisition of biomechanical properties during tendon development". Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 98 (6): 1436–1449. doi:10.1002/jcb.20776. PMID 16518859. S2CID 39384363.

- ^ Raspanti M, Congiu T, Guizzardi S (March 2002). "Structural aspects of the extracellular matrix of the tendon: an atomic force and scanning electron microscopy study". Archives of Histology and Cytology. 65 (1): 37–43. doi:10.1679/aohc.65.37. PMID 12002609.

- ^ Scott JE, Orford CR, Hughes EW (June 1981). "Proteoglycan-collagen arrangements in developing rat tail tendon. An electron microscopical and biochemical investigation". The Biochemical Journal. 195 (3): 573–581. doi:10.1042/bj1950573. PMC 1162928. PMID 6459082.

- ^ Scott JE (December 2003). "Elasticity in extracellular matrix 'shape modules' of tendon, cartilage, etc. A sliding proteoglycan-filament model". The Journal of Physiology. 553 (Pt 2): 335–343. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2003.050179. PMC 2343561. PMID 12923209.

- ^ McNeilly CM, Banes AJ, Benjamin M, Ralphs JR (December 1996). "Tendon cells in vivo form a three dimensional network of cell processes linked by gap junctions". Journal of Anatomy. 189 (Pt 3): 593–600. PMC 1167702. PMID 8982835.

- ^ a b Benjamin M, Ralphs JR (October 1997). "Tendons and ligaments--an overview" (PDF). Histology and Histopathology. 12 (4): 1135–1144. doi:10.14670/HH-12.1135 (inactive 12 July 2025). PMID 9302572.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2025 (link) - ^ "Having a short Achilles tendon may be an athlete's Achilles heel". Sports Injury Bulletin. Archived from the original on 2007-10-21. Retrieved 2007-10-26.

- ^ Young M (2002). "A review on postural realignment and its muscular and neural components" (PDF). British Journal of Sports Medicine. 9 (12): 51–76. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-04-06. Retrieved 2010-06-23.

- ^ Thorpe CT, Birch HL, Clegg PD, Screen HR (August 2013). "The role of the non-collagenous matrix in tendon function". International Journal of Experimental Pathology. 94 (4): 248–259. doi:10.1111/iep.12027. PMC 3721456. PMID 23718692.

- ^ Hulmes DJ (2002). "Building collagen molecules, fibrils, and suprafibrillar structures". Journal of Structural Biology. 137 (1–2): 2–10. doi:10.1006/jsbi.2002.4450. PMID 12064927.

- ^ Silver FH, Freeman JW, Seehra GP (October 2003). "Collagen self-assembly and the development of tendon mechanical properties". Journal of Biomechanics. 36 (10): 1529–1553. doi:10.1016/S0021-9290(03)00135-0. PMID 14499302.

- ^ Ker RF (December 2002). "The implications of the adaptable fatigue quality of tendons for their construction, repair and function". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. Part A, Molecular & Integrative Physiology. 133 (4): 987–1000. doi:10.1016/S1095-6433(02)00171-X. PMID 12485688.

- ^ Cribb AM, Scott JE (October 1995). "Tendon response to tensile stress: an ultrastructural investigation of collagen:proteoglycan interactions in stressed tendon". Journal of Anatomy. 187 (Pt 2): 423–8. PMC 1167437. PMID 7592005.

- ^ Screen HR, Lee DA, Bader DL, Shelton JC (2004). "An investigation into the effects of the hierarchical structure of tendon fascicles on micromechanical properties". Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part H. 218 (2): 109–119. doi:10.1243/095441104322984004. PMID 15116898. S2CID 46256718.

- ^ Puxkandl R, Zizak I, Paris O, Keckes J, Tesch W, Bernstorff S, et al. (February 2002). "Viscoelastic properties of collagen: synchrotron radiation investigations and structural model". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 357 (1418): 191–197. doi:10.1098/rstb.2001.1033. PMC 1692933. PMID 11911776.

- ^ Gupta HS, Seto J, Krauss S, Boesecke P, Screen HR (February 2010). "In situ multi-level analysis of viscoelastic deformation mechanisms in tendon collagen". Journal of Structural Biology. 169 (2): 183–91. doi:10.1016/j.jsb.2009.10.002. PMID 19822213.

- ^ Thorpe CT, Udeze CP, Birch HL, Clegg PD, Screen HR (November 2012). "Specialization of tendon mechanical properties results from interfascicular differences". Journal of the Royal Society, Interface. 9 (76): 3108–3117. doi:10.1098/rsif.2012.0362. PMC 3479922. PMID 22764132.

- ^ Thorpe CT, Klemt C, Riley GP, Birch HL, Clegg PD, Screen HR (August 2013). "Helical sub-structures in energy-storing tendons provide a possible mechanism for efficient energy storage and return". Acta Biomaterialia. 9 (8): 7948–7956. doi:10.1016/j.actbio.2013.05.004. PMID 23669621.

- ^ Gatt R, Vella Wood M, Gatt A, Zarb F, Formosa C, Azzopardi KM, et al. (September 2015). "Negative Poisson's ratios in tendons: An unexpected mechanical response" (PDF). Acta Biomaterialia. 24: 201–208. doi:10.1016/j.actbio.2015.06.018. PMID 26102335.

- ^ Batson EL, Paramour RJ, Smith TJ, Birch HL, Patterson-Kane JC, Goodship AE. (2003). Equine Vet J. |volume=35 |issue=3 |pages=314–8. Are the material properties and matrix composition of equine flexor and extensor tendons determined by their functions?

- ^ Screen HR, Tanner KE (2012). "Structure & Biomechanics of Biological Composites.". Encyclopaedia of Composites (2nd ed.). Nicolais & Borzacchiello.Pub. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 2928–2939. ISBN 978-0-470-12828-2.

- ^ Nakagawa Y, Totsuka M, Sato T, Fukuda Y, Hirota K (1989). "Effect of disuse on the ultrastructure of the achilles tendon in rats". European Journal of Applied Physiology and Occupational Physiology. 59 (3): 239–242. doi:10.1007/bf02386194. PMID 2583169. S2CID 20626078.

- ^ Reeves ND, Maganaris CN, Ferretti G, Narici MV (June 2005). "Influence of 90-day simulated microgravity on human tendon mechanical properties and the effect of resistive countermeasures". Journal of Applied Physiology. 98 (6): 2278–2286. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.01266.2004. hdl:11379/25397. PMID 15705722. S2CID 10508646.

- ^ a b c d Sharma P, Maffulli N (2006). "Biology of tendon injury: healing, modeling and remodeling" (PDF). Journal of Musculoskeletal & Neuronal Interactions. 6 (2): 181–190. PMID 16849830. Archived (PDF) from the original on Jan 5, 2024.

- ^ a b Maffulli N, Wong J, Almekinders LC (October 2003). "Types and epidemiology of tendinopathy". Clinics in Sports Medicine. 22 (4): 675–692. doi:10.1016/s0278-5919(03)00004-8. PMID 14560540.

- ^ Aström M, Rausing A (July 1995). "Chronic Achilles tendinopathy. A survey of surgical and histopathologic findings". Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 316 (316): 151–164. doi:10.1097/00003086-199507000-00021. PMID 7634699. S2CID 25486134.

- ^ a b c d Sharma P, Maffulli N (January 2005). "Tendon injury and tendinopathy: healing and repair". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume. 87 (1): 187–202. doi:10.2106/JBJS.D.01850. PMID 15634833. S2CID 1111422.

- ^ a b Riley G (February 2004). "The pathogenesis of tendinopathy. A molecular perspective". Rheumatology. 43 (2): 131–142. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keg448. PMID 12867575.

- ^ a b c d e f Wang JH (2006). "Mechanobiology of tendon". Journal of Biomechanics. 39 (9): 1563–1582. doi:10.1016/j.jbiomech.2005.05.011. PMID 16000201.

- ^ Riley GP, Curry V, DeGroot J, van El B, Verzijl N, Hazleman BL, et al. (March 2002). "Matrix metalloproteinase activities and their relationship with collagen remodelling in tendon pathology". Matrix Biology. 21 (2): 185–195. doi:10.1016/S0945-053X(01)00196-2. PMID 11852234.

- ^ Moulin V, Tam BY, Castilloux G, Auger FA, O'Connor-McCourt MD, Philip A, et al. (August 2001). "Fetal and adult human skin fibroblasts display intrinsic differences in contractile capacity". Journal of Cellular Physiology. 188 (2): 211–222. doi:10.1002/jcp.1110. PMID 11424088. S2CID 22026692.

- ^ Boyer MI, Watson JT, Lou J, Manske PR, Gelberman RH, Cai SR (September 2001). "Quantitative variation in vascular endothelial growth factor mRNA expression during early flexor tendon healing: an investigation in a canine model". Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 19 (5): 869–872. doi:10.1016/S0736-0266(01)00017-1. PMID 11562135. S2CID 20903366.

- ^ Berge JC, Storer RW (October 1995). "Intratendinous ossification in birds: A review". Journal of Morphology. 226 (1): 47–77. Bibcode:1995JMorp.226...47B. doi:10.1002/jmor.1052260105. PMID 29865323. S2CID 46926646.

- ^ Organ CL (2006). "Biomechanics of ossified tendons in ornithopod dinosaurs". Paleobiology. 32 (4): 652–665. Bibcode:2006Pbio...32..652O. doi:10.1666/05039.1. S2CID 86568665.