Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Pneumoencephalography

View on Wikipedia| Pneumoencephalography | |

|---|---|

Pneumoencephalography | |

| ICD-9-CM | 87.01 |

| MeSH | D011011 |

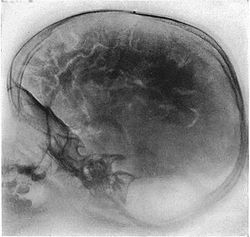

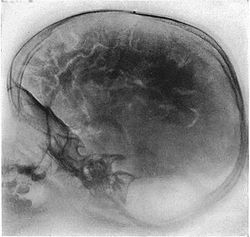

Pneumoencephalography (sometimes abbreviated PEG; also referred to as an "air study") was a common medical procedure in which most of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was drained from around the brain by means of a lumbar puncture and replaced with air, oxygen, or helium to allow the structure of the brain to show up more clearly on an X-ray image. It was derived from ventriculography, an earlier and more primitive method in which the air is injected through holes drilled in the skull.

The procedure was introduced in 1919 by the American neurosurgeon Walter Dandy[1] and was performed extensively until the late 1970s, when it was replaced by more-sophisticated and less-invasive modern neuroimaging techniques.

Procedure

[edit]Though pneumoencephalography was the single most important way of localizing brain lesions of its time, it was nevertheless overly painful and generally not well tolerated by conscious patients. Pneumoencephalography was associated with a wide range of side effects, including headaches and severe vomiting, often lasting well past the procedure.[2] During the study, the patient's entire body would be rotated into different positions in order to allow air to displace the CSF in different areas of the ventricular system and around the brain. The patient would be strapped into an open-backed chair, which allowed the spinal needle to be inserted, and they would need to be secured well, for they would be turned upside down at times during the procedure and then somersaulted into a face-down position in a specific order to follow the air to different areas in the ventricles. This further added to the patient's already heightened level of discomfort (if not anesthetized). A related procedure is pneumomyelography, in which gas is used similarly to investigate the spinal canal. [citation needed]

Limitations

[edit]Pneumoencephalography makes use of plain X-ray images. These are very poor at resolving soft tissues, such as the brain. Moreover, all the structures captured in the image are superimposed on top of each other, which makes it difficult to pick out individual items of interest (unlike modern scanners, which are able to produce fine virtual slices of the body, including of soft tissues). Therefore, pneumoencephalography did not usually image abnormalities directly; rather, their secondary effects. The overall structure of the brain contains crevices and cavities that are filled by the CSF. Both the brain and the CSF produce similar signals on an X-ray image. However, draining the CSF allows for greater contrast between the brain matter and the (now drained) crevices in and around it, which then show up as dark shadows on the X-ray image. The aim of pneumoencephalography is to outline these shadow-forming air-filled structures so that their shape and anatomical location can be examined. Following the procedure, an experienced radiologist reviews the X-ray films to see if the shape or location of these structures have been distorted or shifted by the presence of certain kinds of lesions. This also means that in order to show up on the images, lesions have to either be located right on the edge of the structures or if located elsewhere in the brain, be large enough to push on surrounding healthy tissues to an extent necessary to cause a distortion in the shape of the more distant air-filled cavities (and hence more-distant tumors detected this way tended to be fairly large). [citation needed]

Despite its overall usefulness, there were major portions of the brain and other structures of the head that pneumoencephalography was unable to image. This was partially compensated by increased use of angiography as a complementary diagnostic tool, often in an attempt to infer the condition of non-neurovascular pathology from its secondary vascular characteristics. This additional testing was not without risk, though, particularly due to the rudimentary catheterization techniques and deleterious radiocontrast agents of the day. Another drawback of pneumoencephalography was that the risk and discomfort it carried meant that repeat studies were generally avoided, thus making it difficult to assess disease progression over time. [citation needed]

Current use

[edit]Modern imaging techniques such as MRI and CT have rendered pneumoencephalography obsolete.[3] Widespread clinical use of diagnostic tools using these newer technologies began in the mid-to-late 1970s. These revolutionized the field of neuroimaging by not only being able to non-invasively examine all parts of the brain and its surrounding tissues, but also by doing so in much greater detail than previously available with plain X-rays, therefore making it possible to directly visualize and precisely localize soft-tissue abnormalities inside the skull. This led to significantly improved patient outcomes while reducing discomfort.[4] Today, pneumoencephalography is limited to the research field and is used under rare circumstances [citation needed].

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Walter Dandy". Society of Neurological Surgeons. Archived from the original on 2019-01-10. Retrieved 2011-04-28.

- ^ White, Y. S.; Bell, D. S.; Mellick, B. (February 1973). "Sequelae to pneumoencephalography". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 36 (1). BMJ Group: 146–151. doi:10.1136/jnnp.36.1.146. PMC 494289. PMID 4691687.

- ^ Greenberg, Mark (2010). Handbook of Neurosurgery. Thieme.

- ^ Leeds, NE; Kieffer, SA (November 2000). "Evolution of diagnostic neuroradiology from 1904 to 1999" (PDF). Radiology. 217 (2): 309–18. doi:10.1148/radiology.217.2.r00nv45309. PMID 11058623. S2CID 14639546. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-06-17.

External links

[edit]- Neuroradiology in the pre CT era – Presentation about historical neuroradiology techniques from the Yale Medical School. Pneumoencephalography discussion begins approximately 21 minutes into the presentation.