Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Repressor

View on Wikipedia

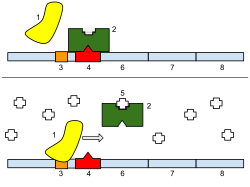

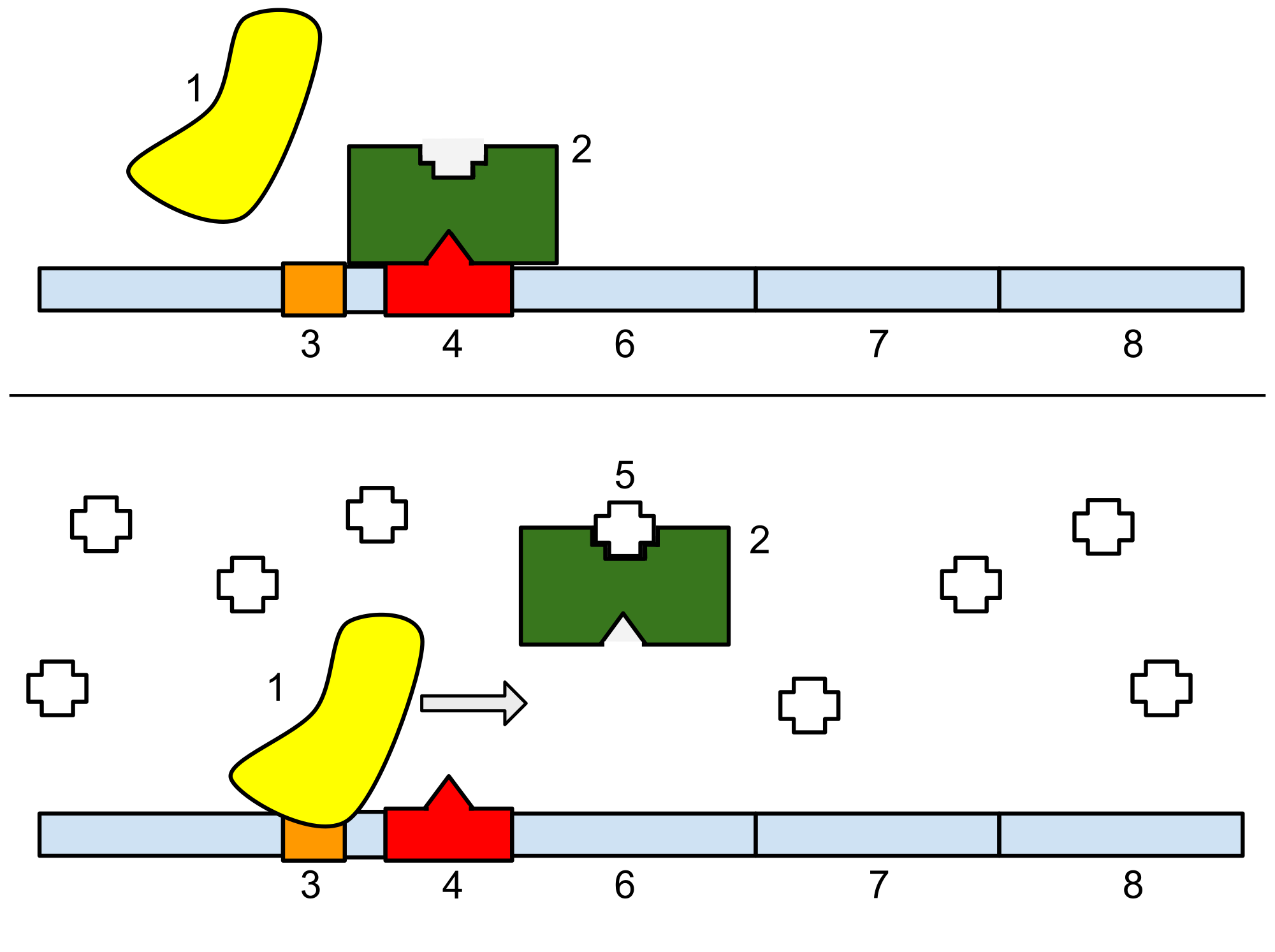

In molecular genetics, a repressor is a DNA- or RNA-binding protein that inhibits the expression of one or more genes by binding to the operator or associated silencers. A DNA-binding repressor blocks the attachment of RNA polymerase to the promoter, thus preventing transcription of the genes into messenger RNA. An RNA-binding repressor binds to the mRNA and prevents translation of the mRNA into protein. This blocking or reducing of expression is called repression.

Function

[edit]If an inducer, a molecule that initiates the gene expression, is present, then it can interact with the repressor protein and detach it from the operator. RNA polymerase then can transcribe the message (expressing the gene). A co-repressor is a molecule that can bind to the repressor and make it bind to the operator tightly, which decreases transcription.

A repressor that binds with a co-repressor is termed an aporepressor or inactive repressor. One type of aporepressor is the trp repressor, an important metabolic protein in bacteria. The above mechanism of repression is a type of a feedback mechanism because it only allows transcription to occur if a certain condition is present: the presence of specific inducer(s). In contrast, an active repressor binds directly to an operator to repress gene expression.

While repressors are more commonly found in prokaryotes, they are rare in eukaryotes. Furthermore, most known eukaryotic repressors are found in simple organisms (e.g., yeast), and act by interacting directly with activators.[1] This contrasts prokaryotic repressors which can also alter DNA or RNA structure.

Within the eukaryotic genome are regions of DNA known as silencers. These are DNA sequences that bind to repressors to partially or fully repress a gene. Silencers can be located several bases upstream or downstream from the actual promoter of the gene. Repressors can also have two binding sites: one for the silencer region and one for the promoter. This causes chromosome looping, allowing the promoter region and the silencer region to come in proximity of each other.

Examples of Repressors

[edit]lac operon repressor

[edit]The lacZYA operon houses genes encoding proteins needed for lactose breakdown.[2] The lacI gene codes for a protein called "the repressor" or "the lac repressor", which functions to repressor of the lac operon.[2] The gene lacI is situated immediately upstream of lacZYA but is transcribed from a lacI promoter.[2] The lacI gene synthesizes LacI repressor protein. The LacI repressor protein represses lacZYA by binding to the operator sequence lacO.[2]

The lac repressor is constitutively expressed and usually bound to the operator region of the promoter, which interferes with the ability of RNA polymerase (RNAP) to begin transcription of the lac operon.[2] In the presence of the inducer allolactose, the repressor changes conformation, reduces its DNA binding strength and dissociates from the operator DNA sequence in the promoter region of the lac operong. RNAP is then able to bind to the promoter and begin transcription of the lacZYA gene.[2]

met operon repressor

[edit]An example of a repressor protein is the methionine repressor MetJ. MetJ interacts with DNA bases via a ribbon-helix-helix (RHH) motif.[3] MetJ is a homodimer consisting of two monomers, which each provides a beta ribbon and an alpha helix. Together, the beta ribbons of each monomer come together to form an antiparallel beta-sheet which binds to the DNA operator ("Met box") in its major groove. Once bound, the MetJ dimer interacts with another MetJ dimer bound to the complementary strand of the operator via its alpha helices. AdoMet binds to a pocket in MetJ that does not overlap the site of DNA binding.

The Met box has the DNA sequence AGACGTCT, a palindrome (it shows dyad symmetry) allowing the same sequence to be recognized on either strand of the DNA. The junction between C and G in the middle of the Met box contains a pyrimidine-purine step that becomes positively supercoiled forming a kink in the phosphodiester backbone. This is how the protein checks for the recognition site as it allows the DNA duplex to follow the shape of the protein. In other words, recognition happens through indirect readout of the structural parameters of the DNA, rather than via specific base sequence recognition.

Each MetJ dimer contains two binding sites for the cofactor S-Adenosyl methionine (SAM) which is a product in the biosynthesis of methionine. When SAM is present, it binds to the MetJ protein, increasing its affinity for its cognate operator site, which halts transcription of genes involved in methionine synthesis. When SAM concentration becomes low, the repressor dissociates from the operator site, allowing more methionine to be produced.

L-arabinose operon repressor

[edit]The L-arabinose operon houses genes coding for arabinose-digesting enzymes. These function to break down arabinose as an alternative source for energy when glucose is low or absent.[4] The operon consists of a regulatory repressor gene (araC), three control sites (ara02, ara01, araI1, and araI2), two promoters (Parac/ParaBAD) and three structural genes (araBAD). Once produced, araC acts as repressor by binding to the araI region to form a loop which prevents polymerases from binding to the promotor and transcribing the structural genes into proteins.

In the absence of Arabinose and araC (repressor), loop formation is not initiated and structural gene expression will be lower. In the absence of Arabinose but presence of araC, araC regions form dimers, and bind to bring ara02 and araI1 domains closer by loop formation.[5] In the presence of both Arabinose and araC, araC binds with the arabinose and acts as an activator. This conformational change in the araC no longer can form a loop, and the linear gene segment promotes RNA polymerase recruitment to the structural araBAD region.[4]

+

Flowing Locus C (Epigenetic Repressor)

[edit]The FLC operon is a conserved eukaryotic locus that is negatively associated with flowering via repression of genes needed for the development of the meristem to switch to a floral state in the plant species Arabidopsis thaliana. FLC expression has been shown be regulated by the presence of FRIGIDA, and negatively correlates with decreases in temperature resulting in the prevention of vernalization.[6] The degree to which expression decreases depends on the temperature and exposure time as seasons progress. After the downregulation of FLC expression, the potential for flowering is enabled. The regulation of FLC expression involves both genetic and epigenetic factors such as histone methylation and DNA methylation.[7] Furthermore, a number of genes are cofactors act as negative transcription factors for FLC genes.[8] FLC genes also have a large number of homologues across species that allow for specific adaptations in a range of climates.[9]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Clark, David P.; Pazdernik, Nanette J.; McGehee, Michelle R. (2019-01-01), Clark, David P.; Pazdernik, Nanette J.; McGehee, Michelle R. (eds.), "Chapter 17 - Regulation of Transcription in Eukaryotes", Molecular Biology (Third Edition), Academic Cell, pp. 560–580, ISBN 978-0-12-813288-3, retrieved 2020-12-02

- ^ a b c d e f Slonczewski, Joan, and John Watkins. Foster. Microbiology: An Evolving Science. New York: W.W. Norton &, 2009. Print.

- ^ Somers & Phillips (1992). "Crystal structure of the met repressor-operator complex at 2.8 A resolution reveals DNA recognition by beta-strands". Nature. 359 (6394): 387–393. Bibcode:1992Natur.359..387S. doi:10.1038/359387a0. PMID 1406951. S2CID 29799322.

- ^ a b Voet, Donald (2011). Biochemistry. Voet, Judith G. (4th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-57095-1. OCLC 690489261.

- ^ Harmer, Tara; Wu, Martin; Schleif, Robert (2001-01-16). "The role of rigidity in DNA looping-unlooping by AraC". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 98 (2): 427–431. Bibcode:2001PNAS...98..427H. doi:10.1073/pnas.98.2.427. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 14602. PMID 11209047.

- ^ Shindo, Chikako; Aranzana, Maria Jose; Lister, Clare; Baxter, Catherine; Nicholls, Colin; Nordborg, Magnus; Dean, Caroline (June 2005). "Role of FRIGIDA and FLOWERING LOCUS C in Determining Variation in Flowering Time of Arabidopsis". Plant Physiology. 138 (2): 1163–1173. doi:10.1104/pp.105.061309. ISSN 0032-0889. PMC 1150429. PMID 15908596.

- ^ Johanson, U.; West, J.; Lister, C.; Michaels, S.; Amasino, R.; Dean, C. (2000-10-13). "Molecular analysis of FRIGIDA, a major determinant of natural variation in Arabidopsis flowering time". Science. 290 (5490): 344–347. Bibcode:2000Sci...290..344J. doi:10.1126/science.290.5490.344. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 11030654.

- ^ Finnegan, E. Jean; Kovac, Kathryn A.; Jaligot, Estelle; Sheldon, Candice C.; Peacock, W. James; Dennis, Elizabeth S. (2005). "The downregulation of FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC) expression in plants with low levels of DNA methylation and by vernalization occurs by distinct mechanisms". The Plant Journal. 44 (3): 420–432. doi:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02541.x. ISSN 1365-313X. PMID 16236152.

- ^ Sharma, Neha; Ruelens, Philip; D'hauw, Mariëlla; Maggen, Thomas; Dochy, Niklas; Torfs, Sanne; Kaufmann, Kerstin; Rohde, Antje; Geuten, Koen (February 2017). "A Flowering Locus C Homolog Is a Vernalization-Regulated Repressor in Brachypodium and Is Cold Regulated in Wheat1[OPEN]". Plant Physiology. 173 (2): 1301–1315. doi:10.1104/pp.16.01161. ISSN 0032-0889. PMC 5291021. PMID 28034954.

External links

[edit]- Repressor+Proteins at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)