Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Alpha helix

View on Wikipedia

An alpha helix (or α-helix) is a sequence of amino acids in a protein that are twisted into a coil (a helix).

The alpha helix is the most common structural arrangement in the secondary structure of proteins. It is also the most extreme type of local structure, and it is the local structure that is most easily predicted from a sequence of amino acids.

The alpha helix has a right-handed helix conformation in which every backbone N−H group hydrogen bonds to the backbone C=O group of the amino acid that is four residues earlier in the protein sequence.

Other names

[edit]The alpha helix is also commonly called a:

- Pauling–Corey–Branson α-helix (from the names of three scientists who described its structure)

- 3.613-helix because there are 3.6 amino acids in one ring, with 13 atoms being involved in the ring formed by the hydrogen bond (starting with amidic hydrogen and ending with carbonyl oxygen)[2]

Discovery

[edit]In the early 1930s, William Astbury showed that there were drastic changes in the X-ray fiber diffraction of moist wool or hair fibers upon significant stretching. The data suggested that the unstretched fibers had a coiled molecular structure with a characteristic repeat of ≈5.1 ångströms (0.51 nanometres).

Astbury initially proposed a linked-chain structure for the fibers. He later joined other researchers (notably the American chemist Maurice Huggins) in proposing that:

- the unstretched protein molecules formed a helix (which he called the α-form)

- the stretching caused the helix to uncoil, forming an extended state (which he called the β-form).

Although incorrect in their details, Astbury's models of these forms were correct in essence and correspond to modern elements of secondary structure, the α-helix and the β-strand (Astbury's nomenclature was kept), which were developed by Linus Pauling, Robert Corey and Herman Branson in 1951 (see below); that paper showed both right- and left-handed helices, although in 1960 the crystal structure of myoglobin[3] showed that the right-handed form is the common one. Hans Neurath was the first to show that Astbury's models could not be correct in detail, because they involved clashes of atoms.[4] Neurath's paper and Astbury's data inspired H. S. Taylor,[5] Maurice Huggins[6] and Bragg and collaborators[7] to propose models of keratin that somewhat resemble the modern α-helix.

Two key developments in the modeling of the modern α-helix were: the correct bond geometry, thanks to the crystal structure determinations of amino acids and peptides and Pauling's prediction of planar peptide bonds; and his relinquishing of the assumption of an integral number of residues per turn of the helix. The pivotal moment came in the early spring of 1948, when Pauling caught a cold and went to bed. Being bored, he drew a polypeptide chain of roughly correct dimensions on a strip of paper and folded it into a helix, being careful to maintain the planar peptide bonds. After a few attempts, he produced a model with physically plausible hydrogen bonds. Pauling then worked with Corey and Branson to confirm his model before publication.[8] In 1954, Pauling was awarded his first Nobel Prize "for his research into the nature of the chemical bond and its application to the elucidation of the structure of complex substances"[9] (such as proteins), prominently including the structure of the α-helix.

Structure

[edit]Geometry and hydrogen bonding

[edit]The amino acids in an α-helix are arranged in a right-handed helical structure where each amino acid residue corresponds to a 100° turn in the helix (i.e., the helix has 3.6 residues per turn), and a translation of 1.5 Å (0.15 nm) along the helical axis. Dunitz[10] describes how Pauling's first article on the theme in fact shows a left-handed helix, the enantiomer of the true structure. Short pieces of left-handed helix sometimes occur with a large content of achiral glycine amino acids, but are unfavorable for the other normal, biological L-amino acids. The pitch of the alpha-helix (the vertical distance between consecutive turns of the helix) is 5.4 Å (0.54 nm), which is the product of 1.5 and 3.6. The most important thing is that the N-H group of one amino acid forms a hydrogen bond with the C=O group of the amino acid four residues earlier; this repeated i + 4 → i hydrogen bonding is the most prominent characteristic of an α-helix. Official international nomenclature[11][12] specifies two ways of defining α-helices, rule 6.2 in terms of repeating φ, ψ torsion angles (see below) and rule 6.3 in terms of the combined pattern of pitch and hydrogen bonding. The α-helices can be identified in protein structure using several computational methods, such as DSSP (Define Secondary Structure of Protein).[13]

Similar structures include the 310 helix (i + 3 → i hydrogen bonding) and the π-helix (i + 5 → i hydrogen bonding). The α-helix can be described as a 3.613 helix, since the i + 4 spacing adds three more atoms to the H-bonded loop compared to the tighter 310 helix, and on average, 3.6 amino acids are involved in one ring of α-helix. The subscripts refer to the number of atoms (including the hydrogen) in the closed loop formed by the hydrogen bond.[14]

Residues in α-helices typically adopt backbone (φ, ψ) dihedral angles around (−60°, −45°), as shown in the image at right. In more general terms, they adopt dihedral angles such that the ψ dihedral angle of one residue and the φ dihedral angle of the next residue sum to roughly −105°. As a consequence, α-helical dihedral angles, in general, fall on a diagonal stripe on the Ramachandran diagram (of slope −1), ranging from (−90°, −15°) to (−70°, −35°). For comparison, the sum of the dihedral angles for a 310 helix is roughly −75°, whereas that for the π-helix is roughly −130°. The general formula for the rotation angle Ω per residue of any polypeptide helix with trans isomers is given by the equation[16][17]

- 3 cos Ω = 1 − 4 cos2 φ + ψ/2

The α-helix is tightly packed; there is almost no free space within the helix. The amino-acid side-chains are on the outside of the helix, and point roughly "downward" (i.e., toward the N-terminus), like the branches of an evergreen tree (Christmas tree effect). This directionality is sometimes used in preliminary, low-resolution electron-density maps to determine the direction of the protein backbone.[18]

Stability

[edit]Helices observed in proteins can range from four to over forty residues long, but a typical helix contains about ten amino acids (about three turns). In general, short polypeptides do not exhibit much α-helical structure in solution, since the entropic cost associated with the folding of the polypeptide chain is not compensated for by a sufficient amount of stabilizing interactions. In general, the backbone hydrogen bonds of α-helices are considered slightly weaker than those found in β-sheets, and are readily attacked by the ambient water molecules. However, in more hydrophobic environments such as the plasma membrane, or in the presence of co-solvents such as trifluoroethanol (TFE), or isolated from solvent in the gas phase,[19] oligopeptides readily adopt stable α-helical structure. Furthermore, crosslinks can be incorporated into peptides to conformationally stabilize helical folds. Crosslinks stabilize the helical state by entropically destabilizing the unfolded state and by removing enthalpically stabilized "decoy" folds that compete with the fully helical state.[20] It has been shown that α-helices are more stable, robust to mutations and designable than β-strands in natural proteins,[21] and also in artificially designed proteins.[22]

Visualization

[edit]The three most popular ways of visualizing the alpha-helical secondary structure of oligopeptide sequences are (1) a helical wheel,[23] (2) a wenxiang diagram,[24] and (3) a helical net.[25] Each of these can be visualized with various software packages and web servers. To generate a small number of diagrams, Heliquest[26] can be used for helical wheels, and NetWheels[27] can be used for helical wheels and helical nets. To programmatically generate a large number of diagrams, helixvis[28][29] can be used to draw helical wheels and wenxiang diagrams in the R and Python programming languages.

Experimental determination

[edit]Since the α-helix is defined by its hydrogen bonds and backbone conformation, the most detailed experimental evidence for α-helical structure comes from atomic-resolution X-ray crystallography such as the example shown at right. It is clear that all the backbone carbonyl oxygens point downward (toward the C-terminus) but splay out slightly, and the H-bonds are approximately parallel to the helix axis. Protein structures from NMR spectroscopy also show helices well, with characteristic observations of nuclear Overhauser effect (NOE) couplings between atoms on adjacent helical turns. In some cases, the individual hydrogen bonds can be observed directly as a small scalar coupling in NMR.

There are several lower-resolution methods for assigning general helical structure. The NMR chemical shifts (in particular of the Cα, Cβ and C′) and residual dipolar couplings are often characteristic of helices. The far-UV (170–250 nm) circular dichroism spectrum of helices is also idiosyncratic, exhibiting a pronounced double minimum at around 208 and 222 nm. Infrared spectroscopy is rarely used, since the α-helical spectrum resembles that of a random coil (although these might be discerned by, e.g., hydrogen-deuterium exchange). Finally, cryo electron microscopy is now capable of discerning individual α-helices within a protein, although their assignment to residues is still an active area of research.

Long homopolymers of amino acids often form helices if soluble. Such long, isolated helices can also be detected by other methods, such as dielectric relaxation, flow birefringence, and measurements of the diffusion constant. In stricter terms, these methods detect only the characteristic prolate (long cigar-like) hydrodynamic shape of a helix, or its large dipole moment.

Amino-acid propensities

[edit]Different amino-acid sequences have different propensities for forming α-helical structure. Alanine, uncharged glutamate, leucine, charged arginine, methionine and charged lysine have especially high helix-forming propensities, whereas proline and glycine have poor helix-forming propensities.[30] Proline either breaks or kinks a helix, both because it cannot donate an amide hydrogen bond (because it has none) and because its sidechain interferes sterically with the backbone of the preceding turn – inside a helix, which forces a bend of about 30° in the helix's axis.[14] However, proline is often the first residue of a helix, presumably due to its structural rigidity. At the other extreme, glycine also tends to disrupt helices because its high conformational flexibility makes it entropically expensive to adopt the relatively constrained α-helical structure.

Table of standard amino acid alpha-helical propensities

[edit]Estimated differences in free energy change, Δ(ΔG), estimated in kcal/mol per residue in an α-helical configuration, relative to alanine arbitrarily set as zero. Higher numbers (more positive free energy changes) are less favoured. Significant deviations from these average numbers are possible, depending on the identities of the neighbouring residues.

Differences in free energy change per residue[30] Amino acid 3-

letter1-

letterHelical penalty kcal/mol kJ/mol Alanine Ala A 0.00 0.00 Arginine Arg R 0.21 0.88 Asparagine Asn N 0.65 2.72 Aspartic acid Asp D 0.69 2.89 Cysteine Cys C 0.68 2.85 Glutamic acid Glu E 0.40 1.67 Glutamine Gln Q 0.39 1.63 Glycine Gly G 1.00 4.18 Histidine His H 0.61 2.55 Isoleucine Ile I 0.41 1.72 Leucine Leu L 0.21 0.88 Lysine Lys K 0.26 1.09 Methionine Met M 0.24 1.00 Phenylalanine Phe F 0.54 2.26 Proline Pro P 3.16 13.22 Serine Ser S 0.50 2.09 Threonine Thr T 0.66 2.76 Tryptophan Trp W 0.49 2.05 Tyrosine Tyr Y 0.53 2.22 Valine Val V 0.61 2.55

Dipole moment

[edit]A helix has an overall dipole moment due to the aggregate effect of the individual microdipoles from the carbonyl groups of the peptide bond pointing along the helix axis.[31] The effects of this macrodipole are a matter of some controversy. α-helices often occur with the N-terminal end bound by a negatively charged group, sometimes an amino acid side chain such as glutamate or aspartate, or sometimes a phosphate ion. Some regard the helix macrodipole as interacting electrostatically with such groups. Others feel that this is misleading and it is more realistic to say that the hydrogen bond potential of the free NH groups at the N-terminus of an α-helix can be satisfied by hydrogen bonding; this can also be regarded as set of interactions between local microdipoles such as C=O···H−N.[32][33]

Coiled coils

[edit]Coiled-coil α helices are highly stable forms in which two or more helices wrap around each other in a "supercoil" structure. Coiled coils contain a highly characteristic sequence motif known as a heptad repeat, in which the motif repeats itself every seven residues along the sequence (amino acid residues, not DNA base-pairs). The first and especially the fourth residues (known as the a and d positions) are almost always hydrophobic; the fourth residue is typically leucine – this gives rise to the name of the structural motif called a leucine zipper, which is a type of coiled-coil. These hydrophobic residues pack together in the interior of the helix bundle. In general, the fifth and seventh residues (the e and g positions) have opposing charges and form a salt bridge stabilized by electrostatic interactions. Fibrous proteins such as keratin or the "stalks" of myosin or kinesin often adopt coiled-coil structures, as do several dimerizing proteins. A pair of coiled-coils – a four-helix bundle – is a very common structural motif in proteins. For example, it occurs in human growth hormone and several varieties of cytochrome. The Rop protein, which promotes plasmid replication in bacteria, is an interesting case in which a single polypeptide forms a coiled-coil and two monomers assemble to form a four-helix bundle.

Facial arrangements

[edit]The amino acids that make up a particular helix can be plotted on a helical wheel, a representation that illustrates the orientations of the constituent amino acids (see the article for leucine zipper for such a diagram). Often in globular proteins, as well as in specialized structures such as coiled-coils and leucine zippers, an α-helix will exhibit two "faces" – one containing predominantly hydrophobic amino acids oriented toward the interior of the protein, in the hydrophobic core, and one containing predominantly polar amino acids oriented toward the solvent-exposed surface of the protein.

Changes in binding orientation also occur for facially-organized oligopeptides. This pattern is especially common in antimicrobial peptides, and many models have been devised to describe how this relates to their function. Common to many of them is that the hydrophobic face of the antimicrobial peptide forms pores in the plasma membrane after associating with the fatty chains at the membrane core.[34][35]

Larger-scale assemblies

[edit]

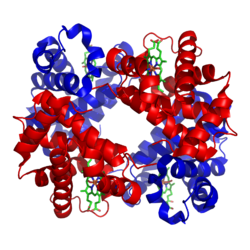

Myoglobin and hemoglobin, the first two proteins whose structures were solved by X-ray crystallography, have very similar folds made up of about 70% α-helix, with the rest being non-repetitive regions, or "loops" that connect the helices. In classifying proteins by their dominant fold, the Structural Classification of Proteins database maintains a large category specifically for all-α proteins.

Hemoglobin then has an even larger-scale quaternary structure, in which the functional oxygen-binding molecule is made up of four subunits.

Functional roles

[edit]

DNA binding

[edit]α-Helices have particular significance in DNA binding motifs, including helix-turn-helix motifs, leucine zipper motifs and zinc finger motifs. This is because of the convenient structural fact that the diameter of an α-helix is about 12 Å (1.2 nm) including an average set of sidechains, about the same as the width of the major groove in B-form DNA, and also because coiled-coil (or leucine zipper) dimers of helices can readily position a pair of interaction surfaces to contact the sort of symmetrical repeat common in double-helical DNA.[36] An example of both aspects is the transcription factor Max (see image at left), which uses a helical coiled coil to dimerize, positioning another pair of helices for interaction in two successive turns of the DNA major groove.

Membrane spanning

[edit]α-Helices are also the most common protein structure element that crosses biological membranes (transmembrane protein),[37] presumably because the helical structure can satisfy all backbone hydrogen-bonds internally, leaving no polar groups exposed to the membrane if the sidechains are hydrophobic. Proteins are sometimes anchored by a single membrane-spanning helix, sometimes by a pair, and sometimes by a helix bundle, most classically consisting of seven helices arranged up-and-down in a ring such as for rhodopsins (see image at right) and other G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs). The structural stability between pairs of α-Helical transmembrane domains rely on conserved membrane interhelical packing motifs, for example, the Glycine-xxx-Glycine (or small-xxx-small) motif.[38]

Mechanical properties

[edit]α-Helices under axial tensile deformation, a characteristic loading condition that appears in many alpha-helix-rich filaments and tissues, results in a characteristic three-phase behavior of stiff-soft-stiff tangent modulus.[39] Phase I corresponds to the small-deformation regime during which the helix is stretched homogeneously, followed by phase II, in which alpha-helical turns break mediated by the rupture of groups of H-bonds. Phase III is typically associated with large-deformation covalent bond stretching.

Dynamical features

[edit]Alpha-helices in proteins may have low-frequency accordion-like motion as observed by the Raman spectroscopy[40] and analyzed via the quasi-continuum model.[41][42] Helices not stabilized by tertiary interactions show dynamic behavior, which can be mainly attributed to helix fraying from the ends.[43]

Helix–coil transition

[edit]Homopolymers of amino acids (such as polylysine) can adopt α-helical structure at low temperature that is "melted out" at high temperatures. This helix–coil transition was once thought to be analogous to protein denaturation. The statistical mechanics of this transition can be modeled using an elegant transfer matrix method, characterized by two parameters: the propensity to initiate a helix and the propensity to extend a helix.

In art

[edit]

At least five artists have made explicit reference to the α-helix in their work: Julie Newdoll in painting and Julian Voss-Andreae, Bathsheba Grossman, Byron Rubin, and Mike Tyka in sculpture.

San Francisco area artist Julie Newdoll,[44] who holds a degree in microbiology with a minor in art, has specialized in paintings inspired by microscopic images and molecules since 1990. Her painting "Rise of the Alpha Helix" (2003) features human figures arranged in an α helical arrangement. According to the artist, "the flowers reflect the various types of sidechains that each amino acid holds out to the world".[44] This same metaphor is also echoed from the scientist's side: "β sheets do not show a stiff repetitious regularity but flow in graceful, twisting curves, and even the α-helix is regular more in the manner of a flower stem, whose branching nodes show the influence of environment, developmental history, and the evolution of each part to match its own idiosyncratic function."[14]

Julian Voss-Andreae is a German-born sculptor with degrees in experimental physics and sculpture. Since 2001 Voss-Andreae creates "protein sculptures"[45] based on protein structure with the α-helix being one of his preferred objects. Voss-Andreae has made α-helix sculptures from diverse materials including bamboo and whole trees. A monument Voss-Andreae created in 2004 to celebrate the memory of Linus Pauling, the discoverer of the α-helix, is fashioned from a large steel beam rearranged in the structure of the α-helix. The 10-foot-tall (3 m), bright-red sculpture stands in front of Pauling's childhood home in Portland, Oregon.

Ribbon diagrams of α-helices are a prominent element in the laser-etched crystal sculptures of protein structures created by artist Bathsheba Grossman, such as those of insulin, hemoglobin, and DNA polymerase.[46] Byron Rubin is a former protein crystallographer now professional sculptor in metal of proteins, nucleic acids, and drug molecules – many of which featuring α-helices, such as subtilisin, human growth hormone, and phospholipase A2.[47]

Mike Tyka is a computational biochemist at the University of Washington working with David Baker. Tyka has been making sculptures of protein molecules since 2010 from copper and steel, including ubiquitin and a potassium channel tetramer.[48]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Animated GIF made by adapting a 3D model from Alpha helix - Proteopedia, Life in 3D". proteopedia.org.

- ^ Voet, Donald; Voet, Judith G. (2011). Biochemistry (4th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. p. 226. ISBN 978-0-470-57095-1. OCLC 690489261.

- ^ Kendrew JC, Dickerson RE, Strandberg BE, Hart RG, Davies DR, Phillips DC, Shore VC (February 1960). "Structure of myoglobin: A three-dimensional Fourier synthesis at 2 Å resolution". Nature. 185 (4711): 422–7. Bibcode:1960Natur.185..422K. doi:10.1038/185422a0. PMID 18990802. S2CID 4167651.

- ^ Neurath H (1940). "Intramolecular folding of polypeptide chains in relation to protein structure". Journal of Physical Chemistry. 44 (3): 296–305. doi:10.1021/j150399a003.

- ^ Taylor HS (1942). "Large molecules through atomic spectacles". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 85 (1): 1–12. JSTOR 985121.

- ^ Huggins M (1943). "The structure of fibrous proteins". Chemical Reviews. 32 (2): 195–218. doi:10.1021/cr60102a002.

- ^ Bragg WL, Kendrew JC, Perutz MF (1950). "Polypeptide chain configurations in crystalline proteins". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, Series A. 203 (1074): 321–?. Bibcode:1950RSPSA.203..321B. doi:10.1098/rspa.1950.0142. S2CID 93804323.

- ^ Pauling L, Corey RB, Branson HR (April 1951). "The structure of proteins; two hydrogen-bonded helical configurations of the polypeptide chain". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 37 (4): 205–11. Bibcode:1951PNAS...37..205P. doi:10.1073/pnas.37.4.205. PMC 1063337. PMID 14816373.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1954".

- ^ Dunitz J (2001). "Pauling's Left-Handed α-Helix". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 40 (22): 4167–4173. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20011119)40:22<4167::AID-ANIE4167>3.0.CO;2-Q. PMID 29712120.

- ^ IUPAC-IUB Commission on Biochemical Nomenclature (1970). "Abbreviations and symbols for the description of the conformation of polypeptide chains". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 245 (24): 6489–6497. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)62561-X.

- ^ "Polypeptide Conformations 1 and 2". www.sbcs.qmul.ac.uk. Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- ^ Kabsch W, Sander C (December 1983). "Dictionary of protein secondary structure: pattern recognition of hydrogen-bonded and geometrical features". Biopolymers. 22 (12): 2577–637. doi:10.1002/bip.360221211. PMID 6667333. S2CID 29185760.

- ^ a b c Richardson JS (1981). "The anatomy and taxonomy of protein structure". Advances in Protein Chemistry. 34: 167–339. doi:10.1016/S0065-3233(08)60520-3. ISBN 978-0-12-034234-1. PMID 7020376.

- ^ Lovell SC, Davis IW, Arendall WB, de Bakker PI, Word JM, Prisant MG, Richardson JS, Richardson DC (February 2003). "Structure validation by Calpha geometry: phi,psi and Cbeta deviation". Proteins. 50 (3): 437–50. doi:10.1002/prot.10286. PMID 12557186. S2CID 8358424.

- ^ Dickerson RE, Geis I (1969), Structure and Action of Proteins, Harper, New York

- ^ Zorko, Matjaž (2010). "Structural Organization of Proteins". In Langel, Ülo; Cravatt, Benjamin F.; Gräslund, Astrid; von Heijne, Gunnar; Land, Tiit; Niessen, Sherry; Zorko, Matjaž (eds.). Introduction to Peptides and Proteins. Boca Raton: CRC Press. pp. 36–57. ISBN 978-1-4398-8204-7.

- ^ Terwilliger TC (March 2010). "Rapid model building of alpha-helices in electron-density maps". Acta Crystallographica Section D. 66 (Pt 3): 268–75. Bibcode:2010AcCrD..66..268T. doi:10.1107/S0907444910000314. PMC 2827347. PMID 20179338.

- ^ Hudgins RR, Jarrold MF (1999). "Helix Formation in Unsolvated Alanine-Based Peptides: Helical Monomers and Helical Dimers". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 121 (14): 3494–3501. Bibcode:1999JAChS.121.3494H. doi:10.1021/ja983996a.

- ^ Kutchukian PS, Yang JS, Verdine GL, Shakhnovich EI (April 2009). "All-atom model for stabilization of alpha-helical structure in peptides by hydrocarbon staples". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 131 (13): 4622–7. Bibcode:2009JAChS.131.4622K. doi:10.1021/ja805037p. PMC 2735086. PMID 19334772.

- ^ Abrusan G, Marsh JA (2016). "Alpha helices are more robust to mutations than beta strands". PLOS Computational Biology. 12 (12) e1005242. Bibcode:2016PLSCB..12E5242A. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005242. PMC 5147804. PMID 27935949.

- ^ Rocklin GJ, et al. (2017). "Global analysis of protein folding using massively parallel design, synthesis, and testing". Science. 357 (6347): 168–175. Bibcode:2017Sci...357..168R. doi:10.1126/science.aan0693. PMC 5568797. PMID 28706065.

- ^ Schiffer M, Edmundson AB (1967). "Use of helical wheels to represent the structures of proteins and to identify segments with helical potential". Biophysical Journal. 7 (2): 121–135. Bibcode:1967BpJ.....7..121S. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(67)86579-2. PMC 1368002. PMID 6048867.

- ^ Chou KC, Zhang CT, Maggiora GM (1997). "Disposition of amphiphilic helices in heteropolar environments". Proteins: Structure, Function, and Genetics. 28 (1): 99–108. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0134(199705)28:1<99::AID-PROT10>3.0.CO;2-C. PMID 9144795. S2CID 26944184.

- ^ Dunnill P (1968). "The Use of Helical Net-Diagrams to Represent Protein Structures". Biophysical Journal. 8 (7): 865–875. Bibcode:1968BpJ.....8..865D. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(68)86525-7. PMC 1367563. PMID 5699810.

- ^ Gautier R, Douguet D, Antonny B, Drin G (2008). "HELIQUEST: a web server to screen sequences with specific alpha-helical properties". Bioinformatics. 24 (18): 2101–2102. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btn392. PMID 18662927.

- ^ Mol AR, Castro MS, Fontes W (2018). "NetWheels: A web application to create high quality peptide helical wheel and net projections". bioRxiv. doi:10.1101/416347. S2CID 92137153.

- ^ Wadhwa RR, Subramanian V, Stevens-Truss R (2018). "Visualizing alpha-helical peptides in R with helixvis". Journal of Open Source Software. 3 (31): 1008. Bibcode:2018JOSS....3.1008W. doi:10.21105/joss.01008. S2CID 56486576.

- ^ Subramanian V, Wadhwa RR, Stevens-Truss R (2020). "Helixvis: Visualize alpha-helical peptides in Python". ChemRxiv.

- ^ a b Pace CN, Scholtz JM (1998). "A helix propensity scale based on experimental studies of peptides and proteins". Biophysical Journal. 75 (1): 422–427. Bibcode:1998BpJ....75..422N. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77529-0. PMC 1299714. PMID 9649402.

- ^ Hol WG, van Duijnen PT, Berendsen HJ (1978). "The alpha helix dipole and the properties of proteins". Nature. 273 (5662): 443–446. Bibcode:1978Natur.273..443H. doi:10.1038/273443a0. PMID 661956. S2CID 4147335.

- ^ He JJ, Quiocho FA (October 1993). "Dominant role of local dipoles in stabilizing uncompensated charges on a sulfate sequestered in a periplasmic active transport protein". Protein Science. 2 (10): 1643–7. doi:10.1002/pro.5560021010. PMC 2142251. PMID 8251939.

- ^ Milner-White EJ (November 1997). "The partial charge of the nitrogen atom in peptide bonds". Protein Science. 6 (11): 2477–82. doi:10.1002/pro.5560061125. PMC 2143592. PMID 9385654.

- ^ Kohn, Eric M.; Shirley, David J.; Arotsky, Lubov; Picciano, Angela M.; Ridgway, Zachary; Urban, Michael W.; Carone, Benjamin R.; Caputo, Gregory A. (2018-02-04). "Role of Cationic Side Chains in the Antimicrobial Activity of C18G". Molecules. 23 (2): 329. doi:10.3390/molecules23020329. PMC 6017431. PMID 29401708.

- ^ Toke, Orsolya (2005). "Antimicrobial peptides: new candidates in the fight against bacterial infections". Biopolymers. 80 (6): 717–735. doi:10.1002/bip.20286. ISSN 0006-3525. PMID 15880793.

- ^ Branden & Tooze, chapter 10

- ^ Branden & Tooze, chapter 12.

- ^ Nash A, Notman R, Dixon AM (2015). "De novo design of transmembrane helix–helix interactions and measurement of stability in a biological membrane". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes. 1848 (5): 1248–57. doi:10.1016/j.bbamem.2015.02.020. PMID 25732028.

- ^ Ackbarow T, Chen X, Keten S, Buehler MJ (October 2007). "Hierarchies, multiple energy barriers, and robustness govern the fracture mechanics of alpha-helical and beta-sheet protein domains". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 104 (42): 16410–5. Bibcode:2007PNAS..10416410A. doi:10.1073/pnas.0705759104. PMC 2034213. PMID 17925444.

- ^ Painter PC, Mosher LE, Rhoads C (July 1982). "Low-frequency modes in the Raman spectra of proteins". Biopolymers. 21 (7): 1469–72. doi:10.1002/bip.360210715. PMID 7115900.

- ^ Chou KC (December 1983). "Identification of low-frequency modes in protein molecules". The Biochemical Journal. 215 (3): 465–9. doi:10.1042/bj2150465. PMC 1152424. PMID 6362659.

- ^ Chou KC (May 1984). "Biological functions of low-frequency vibrations (phonons). III. Helical structures and microenvironment". Biophysical Journal. 45 (5): 881–9. Bibcode:1984BpJ....45..881C. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(84)84234-4. PMC 1434967. PMID 6428481.

- ^ Fierz B, Reiner A, Kiefhaber T (January 2009). "Local conformational dynamics in alpha-helices measured by fast triplet transfer". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (4): 1057–62. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.1057F. doi:10.1073/pnas.0808581106. PMC 2633579. PMID 19131517.

- ^ a b "Julie Newdoll Scientifically Inspired Art, Music, Board Games". www.brushwithscience.com. Retrieved 2016-04-06.

- ^ Voss-Andreae J (2005). "Protein Sculptures: Life's Building Blocks Inspire Art". Leonardo. 38: 41–45. doi:10.1162/leon.2005.38.1.41. S2CID 57558522.

- ^ Grossman, Bathsheba. "About the Artist". Bathsheba Sculpture. Retrieved 2016-04-06.

- ^ "About". molecularsculpture.com. Retrieved 2016-04-06.

- ^ Tyka, Mike. "About". www.miketyka.com. Retrieved 2016-04-06.

Further reading

[edit]- Tooze J, Brändén CI (1999). Introduction to protein structure. New York: Garland Pub. ISBN 0-8153-2304-2..

- Eisenberg D (September 2003). "The discovery of the alpha-helix and beta-sheet, the principal structural features of proteins". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 100 (20): 11207–10. Bibcode:2003PNAS..10011207E. doi:10.1073/pnas.2034522100. PMC 208735. PMID 12966187.

- Astbury WT, Woods HJ (1931). "The Molecular Weights of Proteins". Nature. 127 (3209): 663–665. Bibcode:1931Natur.127..663A. doi:10.1038/127663b0. S2CID 4133226.

- Astbury WT, Street A (1931). "X-ray studies of the structures of hair, wool and related fibres. I. General". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, Series A. 230: 75–101. Bibcode:1932RSPTA.230...75A. doi:10.1098/rsta.1932.0003.

- Astbury WT (1933). "Some Problems in the X-ray Analysis of the Structure of Animal Hairs and Other Protein Fibers". Trans. Faraday Soc. 29 (140): 193–211. doi:10.1039/tf9332900193.

- Astbury WT, Woods HJ (1934). "X-ray studies of the structures of hair, wool and related fibres. II. The molecular structure and elastic properties of hair keratin". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, Series A. 232 (707–720): 333–394. Bibcode:1934RSPTA.232..333A. doi:10.1098/rsta.1934.0010.

- Astbury WT, Sisson WA (1935). "X-ray studies of the structures of hair, wool and related fibres. III. The configuration of the keratin molecule and its orientation in the biological cell". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, Series A. 150 (871): 533–551. Bibcode:1935RSPSA.150..533A. doi:10.1098/rspa.1935.0121.

- Sugeta H, Miyazawa T (1967). "General Method for Calculating Helical Parameters of Polymer Chains from Bond Lengths, Bond Angles, and Internal-Rotation Angles". Biopolymers. 5 (7): 673–679. doi:10.1002/bip.1967.360050708. S2CID 97785907.

- Wada A (1976). "The alpha-helix as an electric macro-dipole". Advances in Biophysics: 1–63. PMID 797240.

- Chothia C, Levitt M, Richardson D (October 1977). "Structure of proteins: packing of alpha-helices and pleated sheets". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 74 (10): 4130–4. Bibcode:1977PNAS...74.4130C. doi:10.1073/pnas.74.10.4130. PMC 431889. PMID 270659.

- Chothia C, Levitt M, Richardson D (January 1981). "Helix to helix packing in proteins". Journal of Molecular Biology. 145 (1): 215–50. doi:10.1016/0022-2836(81)90341-7. PMID 7265198.

- Hol WG (1985). "The role of the alpha-helix dipole in protein function and structure". Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology. 45 (3): 149–95. doi:10.1016/0079-6107(85)90001-X. PMID 3892583.

- Barlow DJ, Thornton JM (June 1988). "Helix geometry in proteins". Journal of Molecular Biology. 201 (3): 601–19. doi:10.1016/0022-2836(88)90641-9. PMID 3418712.

- Murzin AG, Finkelstein AV (December 1988). "General architecture of the alpha-helical globule". Journal of Molecular Biology. 204 (3): 749–69. doi:10.1016/0022-2836(88)90366-X. PMID 3225849.

External links

[edit]Alpha helix

View on GrokipediaHistory and Discovery

Discovery

The alpha helix was first proposed as a structural motif in proteins through pioneering X-ray diffraction studies on fibrous proteins like keratin conducted in the 1930s and 1940s.[5] British biophysicist William Astbury and his collaborators at the University of Leeds analyzed diffraction patterns from wool and hair fibers, identifying characteristic meridional reflections around 5.1 Å in unstretched keratin, which suggested a repeating polypeptide backbone structure but lacked a precise helical model due to assumptions about integral residues per turn.[4] These observations provided crucial empirical data on protein periodicity, highlighting the need for a configuration that could accommodate hydrogen bonding and stereochemical constraints in the peptide chain.[6] In the late 1940s, amid growing interest in elucidating biomolecular architectures, American chemist Linus Pauling turned to protein structure while recovering from a cold during a 1948 visit to Oxford University.[4] Confined to bed, Pauling sketched helical configurations on paper, intuiting a non-integral helix stabilized by intramolecular hydrogen bonds between peptide carbonyl and amide groups, informed by his earlier resonance theory predicting planar peptide units.[4] Upon returning to the California Institute of Technology, Pauling collaborated with Robert B. Corey and Herman R. Branson to refine the model using physical molecular models and bond length data from amino acid crystals, directly addressing the X-ray patterns from keratin and synthetic polypeptides reported by Astbury and others.[4] Pauling, Corey, and Branson formally proposed the alpha helix in a seminal paper published on February 28, 1951, in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, describing it as a right-handed helix with approximately 3.6 residues per turn and a 5.4 Å pitch, compatible with observed diffraction spacings.[2] This model represented a breakthrough by prioritizing stereochemical feasibility over rigid adherence to integral helical parameters, marking the first accurate depiction of a recurring secondary structure in proteins.[4]Nomenclature

The term "alpha helix" originates from early X-ray diffraction studies of protein fibers, where British physicist William T. Astbury identified distinct conformational states in keratin: the unstretched "alpha" form, characterized by a more compact structure, and the stretched "beta" form.[7] In 1951, Linus Pauling, Robert Corey, and Herman Branson proposed the alpha helix as a specific helical model that aligned with Astbury's alpha form observations, building on X-ray data from fibrous proteins like wool and hair to explain the underlying polypeptide chain arrangement.[8][9] Pauling's work classified the alpha helix as one of several possible regular secondary structures for polypeptides, distinguishing it from the extended beta-sheet conformation (corresponding to Astbury's beta form) and other helical variants such as the tighter 3_{10} helix (with 3 residues per turn) and the wider \pi helix (with 4.4 residues per turn), which were also theoretically derived based on hydrogen bonding patterns and stereochemical constraints.[2] These distinctions arose from model-building efforts emphasizing stable, repeating hydrogen bonds along the backbone, positioning the alpha helix (approximately 3.6 residues per turn) as the most favorable for natural proteins.[2][10] Common synonyms include the "Pauling-Corey-Branson \alpha-helix," honoring its proposers, and more specifically the "right-handed alpha helix," which refers to the predominant chiral sense in biological contexts.[2] Left-handed alpha helices, while theoretically possible, are exceedingly rare in proteins due to unfavorable steric interactions with L-amino acid side chains, occurring in only about 31 documented cases as of a 2005 survey across thousands of structures and often limited to short segments rich in glycine.[11][12] In structural biology, the alpha helix is standardized as a right-handed coiled conformation where each backbone N-H group forms a hydrogen bond with the C=O group four residues earlier, as defined by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC).[13] This terminology remains the cornerstone for describing secondary structures in protein databases and analyses, emphasizing its role as a fundamental motif without reference to tertiary context.[14]Structural Characteristics

Geometry and Hydrogen Bonding

The alpha helix is a right-handed helical conformation of the polypeptide backbone, characterized by a tight coil in which the side chains project outward. This structure features approximately 3.6 amino acid residues per turn, resulting in a helical pitch of 5.4 Å, with an axial rise of 1.5 Å per residue along the helix axis.[2][15] These parameters arise from the stereochemical constraints of the planar peptide bond and the L-chirality of amino acids, which favor the right-handed sense to minimize steric clashes between side chains and the backbone.[2] The backbone conformation is defined by specific dihedral angles in the Ramachandran plot: the phi (φ) angle is approximately -57°, and the psi (ψ) angle is approximately -47°.[15] These values position the alpha helix in the allowed region of the plot, enabling a regular, extended structure without significant torsional strain. The peptide bond itself adopts a trans configuration with an omega (ω) angle near 180°, contributing to the overall rigidity.[15] The core stability of the alpha helix stems from intramolecular hydrogen bonds between the backbone amide hydrogen and carbonyl oxygen. Specifically, the C=O group of residue i forms a hydrogen bond with the N-H group of residue i+4, creating a network of bonds nearly parallel to the helix axis.[2] The N...O distance in these hydrogen bonds typically ranges from 2.8 to 3.0 Å, optimizing the bond strength while accommodating the helical geometry. This pattern results in 13 atoms (including hydrogens) per turn, though the structure is often denoted by the i to i+4 bonding motif.[2]Stability Factors

The primary stabilization of the alpha helix arises from intramolecular hydrogen bonds between the backbone carbonyl oxygen of residue and the amide hydrogen of residue , providing a net free energy contribution of approximately 1-2 kcal/mol per bond in aqueous solution.[16] These bonds are marginally stronger in helical conformations than in other secondary structures, such as beta sheets, by about 0.2 kcal/mol, due to optimized geometry and reduced solvent competition.[16] In water, the enthalpic gain from forming these bonds is partially offset by the desolvation penalty of the polar backbone groups, resulting in the modest net stabilization observed experimentally.[17] Side-chain interactions further modulate alpha helix stability, with hydrophobic effects dominating in buried helices and electrostatic interactions, such as salt bridges, playing a key role in solvent-exposed ones. Nonpolar side chains, like those of leucine, isoleucine, and valine, shield the backbone polar groups from water, reducing solvation and enhancing stability by desolvating up to two carbonyl groups per residue; for example, isoleucine and valine provide greater shielding than leucine.[17] In exposed helices, salt bridges between oppositely charged residues (e.g., glutamate-arginine pairs) can contribute 0.5-1.5 kcal/mol to stability, though their effect is context-dependent and often more pronounced on folding kinetics than equilibrium.[18] These interactions vary between buried and exposed environments, where buried salt bridges are rarer but stronger due to lower dielectric screening.[19] At the helix termini, unpaired hydrogen bond donors and acceptors are satisfied by capping motifs, which prevent destabilizing interactions with solvent and link helices to adjacent structures. N-capping motifs, such as those involving serine or threonine side chains forming hydrogen bonds to the exposed N-terminal amide groups, stabilize the first turn by providing alternative partners for up to four backbone NH groups.[20] C-terminal capping, exemplified by the Schellman motif (often featuring glycine at the C-cap position followed by a turn), orients side chains to cap the last four carbonyls through hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic packing, contributing up to 1 kcal/mol per motif in proteins.[21] These motifs are conserved across structures, with consensus sequences like Asn/Ser at N-cap enhancing overall helical propensity.[22] Environmental conditions significantly influence alpha helix formation, with pH, temperature, and solvent altering side-chain ionization, hydrogen bonding, and solvation. At physiological pH, charged residues like aspartate favor N-capping due to electrostatic interactions with the helix dipole, but extreme pH disrupts salt bridges and protonates/deprotonates side chains, reducing stability by 0.5-2 kcal/mol depending on the sequence.[23] Elevated temperatures decrease helical content by weakening propagation (e.g., alanine propensity drops from high at 0°C to lower at 50°C), while solvents like trifluoroethanol (TFE) enhance stability by strengthening backbone hydrogen bonds through reduced water competition.[17] In non-aqueous environments, helix formation becomes more enthalpically driven, with nonpolar solvents favoring hydrophobic side-chain packing.[17] The Zimm-Bragg model quantifies alpha helix stability through statistical mechanics, treating the helix-coil transition as a one-dimensional Ising-like system with two key parameters: the propagation constant , which is the equilibrium constant for extending an existing helix by one residue (typically for average residues, >1 for helix-formers like alanine), and the nucleation constant (around to ), reflecting the unfavorable entropy of initiating a new helix. The partition function for a chain of residues is derived recursively, providing a framework to predict stability from sequence and conditions.[24] This model highlights the cooperative nature of helix formation, where low ensures sharp transitions.Physical Properties

Dipole Moment

The alpha helix possesses a prominent macrodipole due to the parallel alignment of the dipole moments from its peptide bonds along the helical axis. Each peptide bond contributes an individual dipole of approximately 3.5 Debye (D), with the partial negative charge localized on the carbonyl oxygen (C=O) and the partial positive charge on the amide hydrogen (N-H).[25] In the alpha-helical conformation, these microdipoles sum vectorially, with the N-H groups oriented toward the amino (N) terminus and the C=O groups toward the carboxy (C) terminus, resulting in a net positive pole at the N-terminus and a negative pole at the C-terminus.[26] The magnitude of this macrodipole is estimated as the product of 3.5 D per residue and the number of residues (N) in the helix, yielding approximately 3.5N D, though partial cancellation occurs at the termini due to the non-ideal alignment of end-group dipoles.[27] For a typical alpha helix spanning 10–15 residues, the total dipole moment thus ranges from about 40 to 60 D.[28] This dipole influences protein folding and ligand binding through long-range electrostatic attractions and repulsions; for instance, the positive N-terminal pole can stabilize nearby negatively charged residues or ligands, enhancing binding affinity in enzymes and promoting favorable folding pathways.[26] Experimental validation comes from nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) titration studies and site-directed mutagenesis, which demonstrate helix dipole effects on pKa shifts of ionizable groups near helical termini—for example, a histidine residue at the C-terminus of an alpha helix in barnase exhibits a pKa elevation of 1.6 units relative to a non-helical environment, attributed to desolvation and dipole interactions.[29] Similarly, mutagenesis of charged residues in T4 lysozyme mutants reveals stabilizing interactions with the helix dipole, with pKa perturbations of up to 2.1 units observed at low ionic strength, confirming the dipole's role in modulating side-chain ionization.[30][31]Visualization Techniques

The visualization of alpha helices has evolved from rudimentary physical models to sophisticated computational and spectroscopic representations, enabling detailed observation at atomic and molecular scales. In 1951, Linus Pauling and colleagues constructed the first physical space-filling models of the alpha helix using rods and balls to represent atoms and bonds, which allowed them to propose and verify the helical configuration based on stereochemical constraints. These tangible models were instrumental in confirming the right-handed spiral with 3.6 residues per turn, providing an intuitive grasp of the structure before computational tools existed. Contemporary structural models employ ribbon diagrams to depict alpha helices as coiled ribbons or cylindrical segments, simplifying the complex atomic arrangement for clarity in protein illustrations. Pioneered by Jane Richardson in 1981, these diagrams abstract the polypeptide backbone, rendering alpha helices as smooth, twisted ribbons to highlight secondary structure elements without overwhelming detail. Software like PyMOL facilitates the generation of such visualizations by interpolating spline curves through backbone atoms, often displaying helices as thick coils or tubes with customizable colors and transparency for enhanced interpretability in molecular dynamics simulations and structural biology analyses. Spectroscopic techniques offer indirect yet quantitative visualization of alpha helices through their optical properties. Circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy reveals characteristic spectra for alpha-helical content, featuring negative ellipticity minima at approximately 208 nm and 222 nm, arising from the n-π* and π-π* transitions in the amide chromophores aligned parallel to the helix axis. These double minima serve as a diagnostic fingerprint, allowing researchers to estimate helical fractions in solution without crystallographic data, as the intensity ratio near 1:1 at these wavelengths confirms the presence of ordered helical segments. In X-ray crystallography, alpha helices manifest as elongated, rod-like features in electron density maps, where the contiguous density along the helical axis reflects the tightly packed carbonyl and amide groups. Early applications, such as the 1958 myoglobin structure determination, visualized these rods at 2 Å resolution, delineating eight alpha helices as continuous electron density tubes spanning much of the protein core. Modern refinements use software like Coot or Phenix to contour these maps at 1-1.5 σ levels, enabling precise fitting of atomic models to the helical densities for validation of hydrogen bonding patterns.Experimental Determination

Laboratory Methods

X-ray crystallography remains a cornerstone for determining alpha-helical structures in proteins, requiring resolutions better than 2 Å to resolve the characteristic helical density and atomic positions.[32] At lower resolutions, such as 6 Å, early studies identified rod-like electron densities suggestive of alpha helices, but refinement to 2 Å was essential for confirming the right-handed alpha-helical conformation with hydrogen bonding patterns.[33] A seminal example is the 1958 structure of sperm whale myoglobin by John Kendrew and colleagues, initially at low resolution revealing ~75% helical content as dense cylindrical segments, later refined to 2 Å in 1960 to delineate eight alpha helices comprising 123 residues. This work established crystallography's ability to visualize alpha helices through Fourier synthesis, where the 5.4 Å axial repeat and 1.5 Å rise per residue produce distinct helical electron density.[34] Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy identifies alpha helices through chemical shift deviations and nuclear Overhauser effect (NOE) patterns that reflect the i to i+4 backbone hydrogen bonds.[35] The chemical shift index (CSI) method assigns secondary structure by comparing observed chemical shifts of alpha protons (Hα), amide protons (HN), and carbon atoms (Cα, Cβ) to random coil values; alpha-helical residues typically show upfield Hα shifts (< -0.1 ppm) and upfield Cα shifts (<-0.5 ppm) over stretches of four or more consecutive residues.[36] NOE connectivities provide confirmatory evidence, with strong sequential dNN(i,i+1) NOEs between amide protons, medium-range daN(i,i+3) and daN(i,i+4) NOEs between alpha protons and amide protons three or four residues apart, and weak daN(i,i+2) NOEs distinguishing helices from turns.[37] These patterns, observed in 2D or 3D NOESY spectra, have been pivotal in solution structures of small proteins like ubiquitin, where helical segments exhibit characteristic NOE ladders spanning 10-20 residues.[38] Cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) has emerged since the 2010s as a powerful tool for detecting alpha-helical segments in large macromolecular complexes, leveraging resolutions of 3-4 Å to visualize secondary structure without crystallization.[39] The "resolution revolution" enabled by direct electron detectors and advanced image processing reveals alpha helices as tubular densities with a 5-6 Å diameter and 5.4 Å pitch, often using secondary structure element (SSE) detection algorithms like SSEHunter to identify and trace them automatically.[40] In post-2010 applications, cryo-EM has resolved helical bundles in complexes such as RNA polymerase II transcription machineries, where multiple alpha helices in subunits like TFIIH contribute to near-atomic models at 3.5 Å resolution.[39] For even smaller assemblies under 100 kDa, recent advancements achieve 2.5-3 Å resolutions, confirming helical conformations in membrane proteins like ion channels through density fitting.[41] Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy quantifies alpha-helical content by analyzing the amide I band, primarily arising from C=O stretching vibrations of the peptide backbone, which shifts to approximately 1650 cm⁻¹ in helical conformations due to hydrogen bonding.[42] Deconvolution of the amide I region (1600-1700 cm⁻¹) distinguishes alpha helices from other structures, with the 1648-1658 cm⁻¹ component indicating unordered or helical forms, while beta-sheets appear at 1620-1640 cm⁻¹; quantitative analysis via peak area ratios estimates helical percentages in proteins like myoglobin at ~70%.[43] This method is particularly useful for membrane proteins in lipid environments, where attenuated total reflectance (ATR)-FTIR confirms transmembrane alpha helices through the characteristic band position and solvent accessibility effects.[44] Seminal studies on globular proteins established these assignments, enabling rapid secondary structure assessment in non-crystalline samples.[45] Circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy is a widely used technique for estimating alpha-helical content in proteins in solution, based on the differential absorption of left- and right-circularly polarized light in the far-UV region (190-250 nm). Alpha helices produce characteristic negative bands at approximately 222 nm (n-π* transition) and 208 nm (π-π* transition), with the intensity at 222 nm often used to quantify helical fraction via empirical calibration curves or deconvolution algorithms. For example, myoglobin exhibits strong signals corresponding to ~70% helical content. This non-destructive method is valuable for monitoring folding, stability, and ligand-induced changes in helical structure under physiological conditions.[46]Computational Approaches

Computational approaches to alpha helices encompass a range of in silico methods for predicting and analyzing their formation in proteins, from empirical algorithms to advanced simulations and machine learning models. These techniques enable researchers to forecast helical regions based on amino acid sequences, simulate dynamic behavior, and design novel structures, providing insights that complement experimental data. Secondary structure prediction algorithms represent foundational computational tools for identifying alpha helices. The Chou-Fasman method, developed in the 1970s, relies on empirical propensities of amino acids to adopt helical conformations, scanning sequences to identify regions where helix-favoring residues predominate and assigning helical segments based on nucleation and propagation rules.[47] This approach achieves accuracies of approximately 50-60% for helix prediction, limited by its statistical basis but influential in early bioinformatics. Modern machine learning-based methods, such as AlphaFold, have dramatically improved performance by integrating deep neural networks trained on vast structural databases, achieving over 90% accuracy in predicting secondary structures, including alpha helices, through end-to-end learning of spatial arrangements.[48] Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations model the dynamic formation and stability of alpha helices at atomic resolution. Using force fields like AMBER, which parameterize bonded and non-bonded interactions, these simulations track peptide folding over nanosecond to microsecond timescales, revealing helix-coil transitions driven by hydrogen bonding and side-chain effects.[49] For instance, AMBER ff99SB and its variants accurately reproduce experimental helix propensities in alanine-rich peptides, with simulations showing stable helical content aligning with spectroscopic measurements.[50] Ab initio modeling employs quantum mechanical calculations to compute electronic structures of small peptide helices without empirical parameters. Density functional theory (DFT) optimizations of models like Ac-(Ala)_n-NHMe yield precise geometries for alpha helices, including bond lengths and dihedral angles, with energies highlighting the role of intramolecular hydrogen bonds in stabilization.[51] These computations, feasible for systems up to 10-20 residues, provide benchmark data for refining classical force fields used in larger simulations. Recent advances in AI-driven structure prediction have enabled de novo design of proteins featuring alpha helices with high fidelity. Tools like RFdiffusion, a diffusion-based generative model, create novel helical backbones from scratch, followed by sequence optimization via AlphaFold, resulting in experimentally validated structures where predicted helices match observed folds with atomic precision.[52] Between 2021 and 2025, such methods have facilitated designs of helical binders and enzymes, confirming alpha helix formation in non-natural sequences through iterative prediction and validation cycles.[53]Sequence Dependencies

Amino Acid Propensities

The propensity of individual amino acid residues to participate in alpha-helix formation varies significantly, reflecting their intrinsic structural preferences that influence the stability of the helical conformation. These propensities are determined by how well a residue's side chain accommodates the helical geometry without introducing undue strain or entropy penalties. Amino acids with high helix-forming tendencies, such as alanine (Ala), leucine (Leu), and methionine (Met), are frequently observed in helical segments due to their compact or non-polar side chains that minimize steric clashes and allow efficient packing within the helix core.[54][55] In quantitative terms, experimental scales rank these residues based on their relative stabilization energies. For instance, in the helix propensity scale derived from peptide and protein studies, Ala serves as the reference with a ΔΔG of 0 kcal/mol, indicating maximal helix stabilization, while Leu and Met exhibit modestly lower propensities at 0.21 kcal/mol and 0.24 kcal/mol, respectively, reflecting slight destabilization relative to Ala.[3] Conversely, helix-breaking residues like proline (Pro) and glycine (Gly) strongly disfavor alpha-helix incorporation; Pro disrupts the helix due to its rigid pyrrolidine ring, which prevents the necessary backbone hydrogen bonding and introduces a kink, while Gly's lack of a side chain confers excessive flexibility, increasing conformational entropy and opposing the ordered helical state. Gly shows a substantial destabilization with ΔΔG ≈ 1 kcal/mol.[3][55] Several biophysical factors underpin these propensities, including side-chain entropy loss upon helix formation, interactions with the helix macrodipole, and steric hindrance. Bulky or branched side chains, such as in valine, incur high entropy penalties when confined to the helical environment, reducing overall stability, whereas small non-polar groups like in Ala experience minimal such losses. The alpha-helix dipole, arising from aligned peptide bond moments, can further modulate propensities through favorable electrostatic interactions with charged side chains, though this effect is secondary to entropic contributions for non-polar residues. Steric effects are particularly pronounced for Pro, where the cyclic side chain clashes with the preceding residue's backbone.[55][54] These propensities have been rigorously quantified through host-guest peptide experiments, where a reference "host" sequence (often Ala-rich) is systematically mutated at a central "guest" position with different amino acids, and helix stability is assessed via changes in free energy (ΔΔG) using techniques like circular dichroism spectroscopy to monitor helical content. Such studies, pioneered in the late 1980s and compiled in comprehensive scales, isolate intrinsic residue effects by minimizing context dependence, revealing consistent trends across peptides and proteins.[56][54]Propensity Table and Analysis

The propensity of an amino acid to adopt an alpha-helical conformation is quantified by scales derived from statistical analysis of protein structures, where values greater than 1 indicate a preference for helices relative to random coil. These propensities reflect intrinsic tendencies influenced by side-chain properties, such as steric effects, hydrogen bonding potential, and conformational entropy. Modern scales, updated with large datasets from the Protein Data Bank (PDB), provide refined estimates compared to earlier empirical models.[57] The following table presents alpha-helix propensities (Pα) for the 20 standard amino acids, calculated as the ratio of the amino acid's frequency in helical regions to its overall frequency in proteins. Values are from a 2012 analysis of PDB structures across multiple folds, representing a post-2000 dataset with thousands of proteins. Brief rationales highlight key structural factors contributing to each propensity.[57]| Amino Acid | One-Letter Code | Pα | Brief Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alanine | A | 1.41 | Small methyl side chain allows tight packing and minimal steric hindrance in the helix core.[58] |

| Arginine | R | 1.21 | Long guanidino group enables side-chain hydrogen bonding that stabilizes helix ends.[3] |

| Asparagine | N | 0.73 | Polar amide side chain introduces flexibility but limited stabilizing interactions.[58] |

| Aspartic Acid | D | 0.82 | Short charged side chain can form hydrogen bonds but incurs desolvation penalty.[3] |

| Cysteine | C | 0.85 | Thiol group provides weak hydrophobic character but potential for disulfide disruption.[57] |

| Glutamic Acid | E | 1.39 | Charged carboxylate forms salt bridges or hydrogen bonds, particularly at N-terminal caps.[3] |

| Glutamine | Q | 1.26 | Amide side chain supports intra-helical hydrogen bonding without charge repulsion.[58] |

| Glycine | G | 0.44 | Absence of side chain leads to high conformational entropy in the unfolded state.[58] |

| Histidine | H | 0.87 | Imidazole ring offers moderate hydrophobicity but pH-dependent charge effects.[57] |

| Isoleucine | I | 1.04 | Branched hydrophobic side chain fits core but causes slight steric clash.[3] |

| Leucine | L | 1.28 | Non-branched hydrophobic chain buries well in the helix interior.[58] |

| Lysine | K | 1.17 | Long charged side chain facilitates electrostatic interactions at helix surfaces.[3] |

| Methionine | M | 1.26 | Flexible thioether side chain provides hydrophobic stabilization without bulk.[58] |

| Phenylalanine | F | 1.00 | Aromatic ring offers hydrophobicity but potential for pi-stacking distortions.[57] |

| Proline | P | 0.44 | Cyclic side chain restricts phi angle and prevents backbone hydrogen bonding.[58] |

| Serine | S | 0.76 | Hydroxyl group allows hydrogen bonding but increases side-chain entropy loss.[3] |

| Threonine | T | 0.78 | Branched polar side chain causes steric hindrance and beta-branching effects.[58] |

| Tryptophan | W | 1.07 | Bulky indole provides strong hydrophobic burial but limited flexibility.[57] |

| Tyrosine | Y | 0.98 | Aromatic hydroxyl supports hydrogen bonding but introduces bulk.[3] |

| Valine | V | 0.91 | Branched isopropyl side chain leads to steric clashes in the tight helix.[58] |