Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Rubber guard

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

Rubber guard is a Brazilian Jiu-jitsu technique, which involves the practitioner ‘breaking down’ the posture of the opponent to enter into rubber guard, while maintaining a high level of control. It utilizes extensive flexibility to control the opponent with one arm and one leg. The opposite arm in turn is free to attempt submissions, sweeps or to strike the trapped head of the opponent.

Rubber guard, as well as other innovative guard moves, is attributed to Eddie Bravo who adopted it as a staple technique of his 10th Planet Jiu-Jitsu. Modern variations of the Rubber guard have been created in the gi, with the Gubber guard being used by Keenan Cornelius. This is a similar set up to the Rubber guard but involves the use of the lapel to control the opponent's posture.[1]

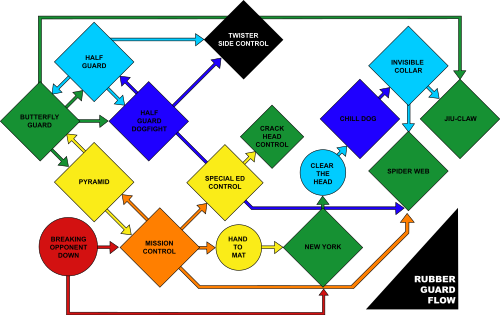

Flowchart

[edit]In the 10th Planet system, the rubber guard follows a flow pattern resembling a branching path or programmatic flowchart; containing six basic "levels" each comprising a primary option and two secondary options.[2]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Gubber Guard - When Closed guard meets the lapel". BjjTribes. 2020-08-12. Retrieved 2020-09-03.

- ^ Bravo, Eddie (2006). Mastering the Rubber Guard: Jiu Jitsu for Mixed Martial Arts Competition. Victory Belt Publishing. p. 272. ISBN 0-9777315-9-6.

Rubber guard

View on GrokipediaHistory

Origins

The exact origins of the rubber guard position remain unknown, with no definitive documentation tracing its development prior to its appearance in modern competitive grappling.[2] It is speculated to have variations of early Brazilian jiu-jitsu closed guards, though these connections are undocumented and subject to debate among practitioners.[6] The first documented competitive use of the rubber guard occurred in the late 1990s, credited to Brazilian jiu-jitsu black belt Nino Schembri, who employed it as an improvised closed guard variation primarily for controlling the opponent's posture.[2][4] Schembri, known for his exceptional flexibility, showcased elements of the position in no-gi competitions between 1997 and 1999, shifting emphasis from traditional hip escapes to leg-based control and entanglement.[7][5] Schembri has claimed that Eddie Bravo later appropriated his positions, including rubber guard variations, and began naming them as his own innovations.[5] These early applications appeared sporadically in events such as Brazilian grappling trials and international no-gi tournaments, where Schembri's innovative guard work drew attention for its unorthodox reliance on limb flexibility over conventional BJJ mechanics.[8] This laid the groundwork for later systematization by Eddie Bravo, who evolved the position into a structured system in the 2000s.[5]Popularization and Development

Eddie Bravo refined the rubber guard during the early 2000s, drawing inspiration from his performance at the 2003 ADCC World Championships, where he famously submitted Royler Gracie using an early version of the position.[9] This upset victory elevated Bravo's profile in the grappling community and directly influenced his subsequent innovations.[10] Following the event, Jean Jacques Machado, under whom Bravo had trained since the mid-1990s, promoted him to black belt upon his return to the United States, providing the formal recognition that spurred further systematization of his techniques.[11] In 2006, Bravo published Mastering the Rubber Guard, an instructional book that formalized the position as a core element of no-gi jiu-jitsu, highlighting its reliance on inversion, flexibility, and posture control to neutralize opponents in mixed martial arts contexts. The work built on foundational influences, such as the inverted guards employed by competitor Nino Schembri in the late 1990s, but expanded them into a comprehensive system tailored for modern competition.[2] Bravo integrated the rubber guard into the curriculum of his newly founded 10th Planet Jiu-Jitsu academy, established in Los Angeles in 2003 shortly after his black belt promotion.[12] This no-gi-focused affiliation system promoted the rubber guard as a signature innovation, fostering its adoption among practitioners worldwide, including modern competitors like Mason Fowler, who adapted it for success in IBJJF and ADCC events and won the UFC BJJ Championship in 2025.[4][13] The approach's emphasis on creative, high-mobility grappling has since influenced a generation of no-gi athletes through 10th Planet's global network of schools.[14]Description

Position Mechanics

The rubber guard position in Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu is established from the bottom, where the practitioner lies supine with one leg extended such that its shin presses across the opponent's shoulder and neck, while the bottom player's opposite arm grips their own shin over the opponent's back, forming a taut "rubber band" tension that disrupts the top player's posture and mobility.[4][15] The other leg provides additional control, such as pressing the knee into the opponent's bicep or placing the foot on their hip. This configuration creates a dynamic open guard variation, leveraging the legs to encircle and control the opponent's torso without relying on a fully closed guard.[2] Central to the position's effectiveness is the emphasis on spinal inversion and hip elevation by the bottom practitioner, which further off-balances the opponent by elevating the hips toward the ceiling and arching the spine to maximize leverage against the top player's base.[3][16] These biomechanical elements generate upward pressure and rotational torque, making it difficult for the opponent to maintain an upright posture or advance their position. Executing this setup demands exceptional flexibility, particularly in the hips and hamstrings, to achieve the deep leg entanglement and sustained inversion without compromising the bottom player's defensive integrity.[4][2] In no-gi adaptations of the rubber guard, the position contrasts with gi-based grips by prioritizing underhooks to secure the opponent's arms and direct head control to counter stacking attempts, ensuring the bottom player maintains entanglement despite the absence of fabric for additional leverage.[16][3] This focus on body locks and limb isolation enhances the position's viability in gi-less environments, as originally envisioned in the development of the system by Eddie Bravo.[4]Grip and Control Principles

The primary grips in the rubber guard emphasize upper body control to disrupt the opponent's posture and limit their offensive options. A key element is the "forearm shield," where the defender places their forearm against the opponent's neck or collarbone while securing a grip on their own shin, creating a frame that pushes the head downward and prevents the opponent from posturing up.[2] Complementing this is wrist control, typically achieved by trapping the opponent's wrist with the same arm or using a palm-up grip to pull their arm forward, forcing a stooped posture and isolating the limb for further manipulation.[4] These grips rely on precise hand placement rather than raw strength, allowing practitioners to maintain dominance even against larger opponents.[16] Leg configuration in the rubber guard provides foundational stability and rotational leverage through targeted placements. One leg features a knee-to-bicep squeeze, where the knee presses firmly into the opponent's bicep to trap the arm and restrict shoulder movement, enhancing the upper body grips' effectiveness.[4] The other leg involves planting the foot on the opponent's hip, which facilitates hip rotation and off-balancing, enabling the defender to swivel and adjust without exposing vulnerabilities.[16] This setup creates a dynamic web of control, where the legs act as both anchors and levers to counter any attempts at posture recovery.[2] At its core, the rubber guard operates on the principle of "clinch and invert" to deny space and neutralize threats, particularly beneficial for smaller practitioners who prioritize leverage over brute force. By clinching the opponent's posture with the aforementioned grips and inverting the hips slightly, the defender compresses the opponent's frame, reducing their ability to generate power or escape while setting up advantageous angles.[4] This approach exemplifies leverage-based control, as the flexible leg entwinement and arm frames allow even less physically imposing grapplers to dictate the pace and direction of the engagement.[16] Inversion mechanics support this by providing subtle rotational adjustments, though the primary focus remains on grip integrity to sustain the position.[4]Core System

Key Positions

The Rubber Guard system in Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu relies on three primary foundational positions for control and leverage, each emphasizing flexibility and precise limb placement to neutralize the opponent's posture while maintaining offensive potential.[4][3] The Standard Rubber Guard serves as the core stance, where the bottom practitioner breaks down the opponent's posture by placing one shin across the top of their shoulders, typically the right shin on the left shoulder for a right-handed grip. The opposite foot—such as the left—is then inserted inside the opponent's thigh to secure a closed configuration, while the free arm grips the shin near the knee to lock the structure in place, trapping the opponent's arm against their own body for added control. This setup uses the forearm to press against the opponent's collarbone or neck, preventing posture recovery and creating leverage through hip mobility and consistent pressure.[4][2] Mission Control is the primary entry and control position in the rubber guard system, where the bottom practitioner places one foot on the opponent's hip and hooks the elevated leg behind the neck to break posture, while the arm grips the opponent's wrist and pulls it toward the body for additional control. The shin is secured across the back or shoulder, immobilizing the upper body and setting up transitions to further rubber guard positions. This configuration relies on leg leverage and does not require inversion.[4][17] The Truck functions as a half-guard variation integrated into the Rubber Guard framework, where one of the opponent's legs is trapped in a figure-four lock using the bottom player's own legs from a seated or inverted base, often with the body facing away to target the leg for control. Specifically, the bottom player hooks the opponent's trapped ankle with their own foot while securing the knee with the opposite leg, creating a defensive platform that isolates the limb and prevents the opponent from basing effectively. This position acts as a stable base, particularly useful before advancing to full Rubber Guard entries, by limiting the opponent's mobility through the self-entwined leg mechanism.[4]Flowchart Overview

The rubber guard system's flowchart, originally diagrammed by Eddie Bravo in his 2006 book Mastering the Rubber Guard, outlines a hierarchical structure that maps the progression of positions and techniques within the 10th Planet Jiu-Jitsu framework. It commences from the closed guard, where the practitioner faces a postured opponent, and branches into the rubber guard through an inversion maneuver that entwines the legs around the opponent's head and arm to disrupt posture and establish initial control. From this entry point, the flow advances to the Mission Control position as a central node, facilitating further entanglements and offensive chains, before looping into submission options such as the triangle choke or omoplata based on the opponent's responses. This structured hierarchy emphasizes systematic advancement, transforming defensive scenarios into dominant attacking pathways.[18][19] A prominent sequence in the flowchart illustrates the transition from rubber guard to knee to bicep control, where the bottom shin slides inside the opponent's bicep to isolate the arm, progressing to the Truck position for hip and posture manipulation, and culminating in a back take to secure rear dominance. This pathway underscores the no-gi fluidity of the system, relying on body leverage and leg mechanics rather than fabric grips to maintain momentum and adapt to resistance. Additional branches, such as those leading to sweeps or reguards, reinforce the interconnected nature of the flows, allowing practitioners to cycle through options without linear predictability.[20][18] The flowchart's visual design incorporates decision trees to handle opponent reactions, presenting branching paths that guide choices based on specific cues; for instance, if the opponent postures up or pushes away, the diagram directs toward a knee shield recovery or omoplata setup, whereas a forward posture break prompts an immediate armbar progression. These decision points create a programmatic logic, akin to a branching algorithm, ensuring the system remains responsive and versatile across varying resistance levels and skill disparities. By prioritizing adaptability, the chart serves as a foundational tool for training and application, encapsulating the rubber guard's emphasis on proactive control from inverted and entangled positions.[21][19]Techniques

Entries and Setups

Entering the rubber guard from the closed guard begins with a hip escape to position one's shin across the opponent's bicep, disrupting their posture and creating space for inversion.[22] This movement allows the practitioner to invert the hips, swinging the leg upward to hook behind the opponent's head while securing an overhook on the far arm, locking in the initial rubber guard frame.[16] The technique relies on flexibility and timing to prevent the opponent from basing out during the transition.[23] From open guard or half guard, the lockdown serves as a foundational control to facilitate entry by pulling the opponent forward into a vulnerable posture.[24] In half guard, the practitioner applies the lockdown by threading the ankle behind the opponent's knee while framing their hip, then uses a "pimp hand" stiff-arm on the knee to off-balance them before releasing the lockdown to wrap the shin high across the back.[25] Similarly, in open guard, pulling the opponent downward with underhooks combines with the lockdown to bait a forward lean, enabling the shin wrap and inversion to establish the position.[16] These setups emphasize proactive pulling to deny distance, aligning with the system's flowchart sequences for fluid progression.[22] Against standing opponents, particularly in no-gi sparring, the de la Riva hook provides an effective bridge to rubber guard inversion by off-balancing the opponent from a seated open guard.[26] The practitioner inserts the de la Riva hook inside the opponent's lead leg while gripping the ankle or sleeve equivalent, then hip escapes to load the hips and invert, transitioning the hooked leg to wrap the shin behind the head as the opponent steps in.[23] This method exploits the standing base's instability, common in 10th Planet Jiu-Jitsu applications for dynamic entries without gi grips.[25]Attacks and Submissions

The rubber guard position in Brazilian jiu-jitsu serves as a versatile platform for launching submissions by controlling the opponent's posture and isolating limbs through leg entanglements and grips. Key attacks emphasize fluidity and inversion, allowing practitioners to transition between threats while maintaining control. Primary submissions include the triangle choke, omoplata shoulder lock, guillotine choke variations, gogoplata, and armbar, each leveraging the unique mechanics of the rubber guard to create leverage and pressure.[4][2] The triangle choke is executed by first establishing mission control within the rubber guard, where the practitioner's shin presses across the opponent's shoulders to break their posture, trapping one wrist and cupping the knee for added control. From this setup, the bottom player baits a defensive reaction—such as a posture attempt or arm pull—then flows through intermediate positions like New York and Chill Dog to extend the wrapped leg over the opponent's far shoulder, locking the ankles or shins around the neck and one arm while squeezing the thighs to compress the carotid arteries and induce submission. This technique famously highlighted the rubber guard's efficacy when Eddie Bravo submitted Royler Gracie with it at the 2003 ADCC Championships.[4][2][9] The omoplata shoulder lock exploits the rubber guard's inversion potential to trap and torque the opponent's arm. Starting from mission control, the practitioner isolates the target arm by swinging the entangled leg to encircle it, then rolls to their side using hip leverage to position the opponent's elbow against their own hip bone while the leg presses downward on the shoulder. This creates a figure-four lock that hyperextends the shoulder joint, forcing a tap; the rubber guard's flexibility enables seamless entries, often chaining from failed triangle attempts. The omoplata's integration into the system draws inspiration from Nino Schembri's innovative use of leg-based arm attacks in the late 1990s.[4][2][27] Guillotine choke variations from the rubber guard capitalize on posture breaks to transition into a front headlock. In mission control, the shin across the shoulders pulls the opponent's head downward, prompting them to defend by posting an arm or lunging forward, at which point the bottom player wraps one arm around the neck, secures the guillotine grip with the other hand, and squeezes while arching the hips for constriction. Advanced forms, such as the hindulotine, incorporate the entangled leg to prevent escapes and add knee pressure to the trachea or carotid. This submission thrives on the rubber guard's ability to off-balance aggressive top players, turning their momentum against them.[4][2] The gogoplata is a distinctive foot choke originating from the rubber guard, where the practitioner positions their shin over the opponent's shoulder and traps the neck using the foot and instep against the carotid artery. From mission control or related positions like the truck, the bottom player inverts to slide the foot inside the opponent's armpit, then pulls their own head and arm to clasp the shin, applying pressure with the sole of the foot to the neck while the opponent is postured forward. This submission, pioneered by Nino Schembri and popularized in the 10th Planet system, requires significant flexibility and is often chained from failed arm attacks.[4][2] The armbar from rubber guard utilizes the position's leg entanglement to isolate and extend the opponent's elbow. Starting in mission control, the practitioner baits a posture break or arm retrieval, then swings the free leg to hook behind the trapped arm while the rubber guard leg maintains shoulder control. Rolling to the side or bridging the hips elevates the opponent, allowing the bottom player to secure the figure-four leg lock around the arm and squeeze to hyperextend the elbow joint. This attack flows naturally from defensive reactions in the system, such as during triangle defenses.[4][2]Applications

Defensive Uses

The rubber guard serves as a primary defensive mechanism in Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu by denying the opponent's posture through targeted shin pressure, which obstructs knee-cut passes and facilitates guard retention. In this position, the bottom player secures a shin-to-shin grip while threading one leg over the opponent's shoulder to apply downward force on their back, effectively flattening their torso and preventing them from achieving an upright posture necessary for advancing. This technique, developed by Eddie Bravo as part of the 10th Planet Jiu-Jitsu system, leverages the opponent's forward momentum against them, turning potential pass attempts into opportunities for the defender to regain control.[28][3] Additionally, the rubber guard enables stalling and recovery against aggressive top players by incorporating inversion to create crucial distance, allowing the defender to buy time for sweeps or positional resets. By rolling onto the shoulders and using leg entanglements like the lockdown to restrict the opponent's knee line, the bottom player disrupts forward pressure and forces the top player to expend energy without progress, particularly effective in no-gi scenarios where grips are limited. This defensive inversion draws from the system's emphasis on hip mobility, transforming defensive desperation into strategic recovery without exposing the back.[24][29] As a counter to stacking passes, the rubber guard employs leg tension and overhook controls to off-balance the opponent and reverse pressure, especially in no-gi grappling. The defender baits the stack by feigning a flattened position, then uses the meathook grip—securing the armpit with the calf—to trap the opponent in a cocoon-like hold that limits their ability to lift and fold the legs effectively. This creates instability, enabling the bottom player to hip escape or transition to dominant positions like the full mount, as demonstrated in 10th Planet instructional classes where mission control grips further neutralize stacking attempts.[3][30]Training and Drills

Training the rubber guard requires a structured progression emphasizing mobility, technique repetition, and system familiarity to achieve proficiency in this flexible closed guard variation. Practitioners begin with foundational flexibility drills to develop the hip and lower body range necessary for inverting and wrapping the legs around the opponent's upper torso and arm. Daily hip openers, such as the butterfly stretch—where one sits with soles of the feet together and knees pressed toward the mat while leaning forward—and the pigeon pose, which targets the hip rotators by placing one shin across the body in a low lunge, form the core of these routines. Inversion holds, like shoulder stands or wall-supported leg raises to mimic the upside-down entries, further build spinal and hamstring flexibility. These exercises start with short sessions of 5-10 minutes daily, gradually increasing duration and intensity to avoid injury, as recommended in Eddie Bravo's instructional system.[4] Once basic mobility is established, positional sparring refines entry and maintenance skills against dynamic resistance. Drills focus on transitioning from a standard closed guard into rubber guard by breaking the opponent's posture and securing the shin across their neck, with partners providing controlled opposition to simulate real scenarios. Progressions involve drilling specific entries, such as the "New York" setup where the bottom player uses forearm pressure on the biceps to pull the opponent down, repeated in sets of 5-10 reps per side before advancing to chained flows that include sweeps and submission attempts like the omoplata. This method isolates the position to build muscle memory without full exhaustion, allowing for high-volume practice during class sessions.[4][22] System integration ties the rubber guard into the broader 10th Planet Jiu-Jitsu framework through mental and live application exercises. Solo flowchart visualization involves studying the branching sequence of positions—from mission control to the truck and back—mentally rehearsing paths and counters to internalize decision-making under pressure. This is followed by live rolling sessions adapted to 10th Planet rulesets, which emphasize no-gi grappling and prohibit certain traditional grips to encourage the system's fluid, inversion-based movements. These rolls start positionally, such as beginning in rubber guard, and evolve to open sparring, fostering seamless transitions within the ecosystem. The training approaches were pioneered by Eddie Bravo, the system's founder, to make the rubber guard accessible beyond elite flexibility levels.[22][4]Variations

Primary Variations

The New York position is a fundamental variation of the rubber guard characterized by both legs being fully inverted, with one knee positioned to shield the practitioner's face while the other leg traps the opponent's arm and head. This setup provides extreme postural control, pinning the opponent's posting hand to the mat and preventing effective guard passes or strikes, thereby creating opportunities for sweeps or submission chains such as the omoplata and triangle. Developed within Eddie Bravo's 10th Planet Jiu-Jitsu system, it serves as a transitional hub in the rubber guard flowchart for advanced branching into offensive sequences.[1][2]Related Positions

The rubber guard shares conceptual similarities with the closed guard in its emphasis on controlling the opponent between the legs to break posture and set up sweeps or submissions, but it diverges significantly as a no-gi open guard that incorporates inversion and shin placement across the shoulders for control, rather than the closed guard's full leg encirclement around the waist.[31] Unlike the closed guard, which relies on gi collar grips for enhanced upper-body control and stability, the rubber guard lacks these gi-specific tools, making it more reliant on flexibility and leg dexterity to maintain position in no-gi scenarios.[4] The rubber guard also links to the half guard through positions like the Truck, which functions as an open variant of half guard applied from the opponent's back using a figure-four leg entanglement to facilitate leg locks, back takes, or transitions.[4] This shared leg-entanglement mechanic emphasizes dynamic control and submission threats, but the rubber guard prioritizes hip flexibility and inversion over the traditional half guard's knee shield for defensive structure.[2] Modern gi-based lapel guards, such as the worm guard, draw influences from the rubber guard's inversion principles, adapting them for entries where the opponent's lapel is wrapped around the leg to create leverage and off-balance effects similar to rubber guard setups.[32] These adaptations borrow the rubber guard's focus on leg control and flexibility to enhance gi-specific sweeps and transitions, though they incorporate lapel grips absent in no-gi rubber guard applications.[33] Primary variations like Mission Control serve as bridges to these related guards by facilitating shin-to-shoulder control that can transition into half guard or inverted lapel entries.[4]References

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Rbguard_flow.png