Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Triangle

View on Wikipedia

| Triangle | |

|---|---|

| |

| Edges and vertices | 3 |

| Schläfli symbol | {3} (for equilateral) |

| Area | Various methods; see below |

A triangle is a polygon with three corners and three sides, one of the basic shapes in geometry. The corners, also called vertices, are zero-dimensional points while the sides connecting them, also called edges, are one-dimensional line segments. A triangle has three internal angles, each one bounded by a pair of adjacent edges; the sum of angles of a triangle always equals a straight angle (180 degrees or π radians). The triangle is a plane figure and its interior is a planar region. Sometimes an arbitrary edge is chosen to be the base, in which case the opposite vertex is called the apex; the shortest segment between the base and apex is the height. The area of a triangle equals one-half the product of height and base length.

In Euclidean geometry, any two points determine a unique line segment situated within a unique straight line, and any three points that do not all lie on the same straight line determine a unique triangle situated within a unique flat plane. More generally, four points in three-dimensional Euclidean space determine a solid figure called tetrahedron.

In non-Euclidean geometries, three "straight" segments (having zero curvature) also determine a "triangle", for instance, a spherical triangle or hyperbolic triangle. A geodesic triangle is a region of a general two-dimensional surface enclosed by three sides that are straight relative to the surface (geodesics). A curvilinear triangle is a shape with three curved sides, for instance, a circular triangle with circular-arc sides. (This article is about straight-sided triangles in Euclidean geometry, except where otherwise noted.)

Triangles are classified into different types based on their angles and the lengths of their sides. Relations between angles and side lengths are a major focus of trigonometry. In particular, the sine, cosine, and tangent functions relate side lengths and angles in right triangles.

Definition, terminology, and types

[edit]A triangle is a figure consisting of three line segments, each of whose endpoints are connected.[1] This forms a polygon with three sides and three angles. The terminology for categorizing triangles is more than two thousand years old, having been defined in Book One of Euclid's Elements.[2] The names used for modern classification are either a direct transliteration of Euclid's Greek or their Latin translations.

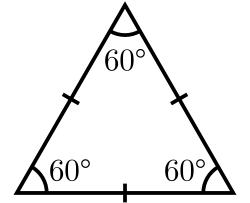

Triangles have many types based on the length of the sides and the angles. A triangle whose sides are all the same length is an equilateral triangle,[3] a triangle with two sides having the same length is an isosceles triangle,[4][a] and a triangle with three different-length sides is a scalene triangle.[7] A triangle in which one of the angles is a right angle is a right triangle, a triangle in which all of its angles are less than that angle is an acute triangle, and a triangle in which one of it angles is greater than that angle is an obtuse triangle.[8] These definitions date back at least to Euclid.[9]

-

Scalene triangle

Appearances

[edit]

All types of triangles are commonly found in real life. In man-made construction, the isosceles triangles may be found in the shape of gables and pediments, and the equilateral triangle can be found in the yield sign.[10] The faces of the Great Pyramid of Giza are sometimes considered to be equilateral, but more accurate measurements show they are isosceles instead.[11] Other appearances are in heraldic symbols as in the flag of Saint Lucia and flag of the Philippines.[12]

Triangles also appear in three-dimensional objects. A polyhedron is a solid whose boundary is covered by flat polygonals known as the faces, sharp corners known as the vertices, and line segments known as the edges. Polyhedra in some cases can be classified, judging from the shape of their faces. For example, when polyhedra have all equilateral triangles as their faces, they are known as deltahedra.[13] Antiprisms have alternating triangles on their sides.[14] Pyramids and bipyramids are polyhedra with polygonal bases and triangles for lateral faces; the triangles are isosceles whenever they are right pyramids and bipyramids. The Kleetope of a polyhedron is a new polyhedron made by replacing each face of the original with a pyramid, and so the faces of a Kleetope will be triangles.[15] More generally, triangles can be found in higher dimensions, as in the generalized notion of triangles known as the simplex, and the polytopes with triangular facets known as the simplicial polytopes.[16]

Properties

[edit]Points, lines, and circles associated with a triangle

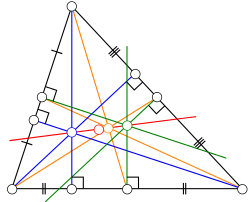

[edit]Each triangle has many special points inside it, on its edges, or otherwise associated with it. They are constructed by finding three lines associated symmetrically with the three sides (or vertices) and then proving that the three lines meet in a single point. An important tool for proving the existence of these points is Ceva's theorem, which gives a criterion for determining when three such lines are concurrent.[17] Similarly, lines associated with a triangle are often constructed by proving that three symmetrically constructed points are collinear; here Menelaus' theorem gives a useful general criterion.[18] In this section, just a few of the most commonly encountered constructions are explained.

A perpendicular bisector of a side of a triangle is a straight line passing through the midpoint of the side and being perpendicular to it, forming a right angle with it.[19] The three perpendicular bisectors meet in a single point, the triangle's circumcenter; this point is the center of the circumcircle, the circle passing through all three vertices.[20] Thales' theorem implies that if the circumcenter is located on the side of the triangle, then the angle opposite that side is a right angle.[21] If the circumcenter is located inside the triangle, then the triangle is acute; if the circumcenter is located outside the triangle, then the triangle is obtuse.[22]

An altitude of a triangle is a straight line through a vertex and perpendicular to the opposite side. This opposite side is called the base of the altitude, and the point where the altitude intersects the base (or its extension) is called the foot of the altitude.[23] The length of the altitude is the distance between the base and the vertex. The three altitudes intersect in a single point, called the orthocenter of the triangle.[24] The orthocenter lies inside the triangle if and only if the triangle is acute.[25]

An angle bisector of a triangle is a straight line through a vertex that cuts the corresponding angle in half. The three angle bisectors intersect in a single point, the incenter, which is the center of the triangle's incircle. The incircle is the circle that lies inside the triangle and touches all three sides. Its radius is called the inradius. There are three other important circles, the excircles; they lie outside the triangle and touch one side, as well as the extensions of the other two. The centers of the incircles and excircles form an orthocentric system.[26] The midpoints of the three sides and the feet of the three altitudes all lie on a single circle, the triangle's nine-point circle.[27] The remaining three points for which it is named are the midpoints of the portion of altitude between the vertices and the orthocenter. The radius of the nine-point circle is half that of the circumcircle. It touches the incircle (at the Feuerbach point) and the three excircles. The orthocenter (blue point), the center of the nine-point circle (red), the centroid (orange), and the circumcenter (green) all lie on a single line, known as Euler's line (red line). The center of the nine-point circle lies at the midpoint between the orthocenter and the circumcenter, and the distance between the centroid and the circumcenter is half that between the centroid and the orthocenter.[27] Generally, the incircle's center is not located on Euler's line.[28][29]

A median of a triangle is a straight line through a vertex and the midpoint of the opposite side, and divides the triangle into two equal areas. The three medians intersect in a single point, the triangle's centroid or geometric barycenter. The centroid of a rigid triangular object (cut out of a thin sheet of uniform density) is also its center of mass: the object can be balanced on its centroid in a uniform gravitational field.[30] The centroid cuts every median in the ratio 2:1, i.e. the distance between a vertex and the centroid is twice the distance between the centroid and the midpoint of the opposite side. If one reflects a median in the angle bisector that passes through the same vertex, one obtains a symmedian. The three symmedians intersect in a single point, the symmedian point of the triangle.[31]

Angles

[edit]

The sum of the measures of the interior angles of a triangle in Euclidean space is always 180 degrees.[32] This fact is equivalent to Euclid's parallel postulate. This allows the determination of the measure of the third angle of any triangle, given the measure of two angles.[33] An exterior angle of a triangle is an angle that is a linear pair (and hence supplementary) to an interior angle. The measure of an exterior angle of a triangle is equal to the sum of the measures of the two interior angles that are not adjacent to it; this is the exterior angle theorem.[34] The sum of the measures of the three exterior angles (one for each vertex) of any triangle is 360 degrees, and indeed, this is true for any convex polygon, no matter how many sides it has.[35]

Another relation between the internal angles and triangles creates a new concept of trigonometric functions. The primary trigonometric functions are sine and cosine, as well as the other functions. They can be defined as the ratio between any two sides of a right triangle.[36] In a scalene triangle, the trigonometric functions can be used to find the unknown measure of either a side or an internal angle; methods for doing so use the law of sines and the law of cosines.[37]

Any three angles that add to 180° can be the internal angles of a triangle. Infinitely many triangles have the same angles, since specifying the angles of a triangle does not determine its size. (A degenerate triangle, whose vertices are collinear, has internal angles of 0° and 180°; whether such a shape counts as a triangle is a matter of convention.[38][39]) The conditions for three angles , , and , each of them between 0° and 180°, to be the angles of a triangle can also be stated using trigonometric functions. For example, a triangle with angles , , and exists if and only if[40]

Similarity and congruence

[edit]

Two triangles are said to be similar, if every angle of one triangle has the same measure as the corresponding angle in the other triangle. The corresponding sides of similar triangles have lengths that are in the same proportion, and this property is also sufficient to establish similarity.[41]

Some basic theorems about similar triangles are:

- If and only if one pair of internal angles of two triangles have the same measure as each other, and another pair also have the same measure as each other, the triangles are similar.[42]

- If and only if one pair of corresponding sides of two triangles are in the same proportion as another pair of corresponding sides, and their included angles have the same measure, then the triangles are similar.[43] (The included angle for any two sides of a polygon is the internal angle between those two sides.)

- If and only if three pairs of corresponding sides of two triangles are all in the same proportion, then the triangles are similar.[b]

Two triangles that are congruent have exactly the same size and shape. All pairs of congruent triangles are also similar, but not all pairs of similar triangles are congruent. Given two congruent triangles, all pairs of corresponding interior angles are equal in measure, and all pairs of corresponding sides have the same length. This is a total of six equalities, but three are often sufficient to prove congruence.[44]

Some individually necessary and sufficient conditions for a pair of triangles to be congruent are:[45]

- SAS Postulate: Two sides in a triangle have the same length as two sides in the other triangle, and the included angles have the same measure.

- ASA: Two interior angles and the side between them in a triangle have the same measure and length, respectively, as those in the other triangle. (This is the basis of surveying by triangulation.)

- SSS: Each side of a triangle has the same length as the corresponding side of the other triangle.

- AAS: Two angles and a corresponding (non-included) side in a triangle have the same measure and length, respectively, as those in the other triangle. (This is sometimes referred to as AAcorrS and then includes ASA above.)

Area

[edit]

In the Euclidean plane, area is defined by comparison with a square of side length , which has area 1. There are several ways to calculate the area of an arbitrary triangle. One of the oldest and simplest is to take half the product of the length of one side (the base) times the corresponding altitude :[46]

This formula can be proven by cutting up the triangle and an identical copy into pieces and rearranging the pieces into the shape of a rectangle of base and height .

If two sides and and their included angle are known, then the altitude can be calculated using trigonometry, , so the area of the triangle is:

Heron's formula, named after Heron of Alexandria, is a formula for finding the area of a triangle from the lengths of its sides , , . Letting be the semiperimeter,[47]

Because the ratios between areas of shapes in the same plane are preserved by affine transformations, the relative areas of triangles in any affine plane can be defined without reference to a notion of distance or squares. In any affine space (including Euclidean planes), every triangle with the same base and oriented area has its apex (the third vertex) on a line parallel to the base, and their common area is half of that of a parallelogram with the same base whose opposite side lies on the parallel line. This affine approach was developed in Book 1 of Euclid's Elements.[48]

Given affine coordinates (such as Cartesian coordinates) , , for the vertices of a triangle, its relative oriented area can be calculated using the shoelace formula,

where is the matrix determinant.[49]

Possible side lengths

[edit]The triangle inequality states that the sum of the lengths of any two sides of a triangle must be greater than or equal to the length of the third side.[50] Conversely, some triangle with three given positive side lengths exists if and only if those side lengths satisfy the triangle inequality.[51] The sum of two side lengths can equal the length of the third side only in the case of a degenerate triangle, one with collinear vertices.

Rigidity

[edit]

Unlike a rectangle, which may collapse into a parallelogram from pressure to one of its points,[52] triangles are sturdy because specifying the lengths of all three sides determines the angles.[53] Therefore, a triangle will not change shape unless its sides are bent or extended or broken or if its joints break; in essence, each of the three sides supports the other two. A rectangle, in contrast, is more dependent on the strength of its joints in a structural sense.

Triangles are strong in terms of rigidity, but while packed in a tessellating arrangement triangles are not as strong as hexagons under compression (hence the prevalence of hexagonal forms in nature). Tessellated triangles still maintain superior strength for cantilevering, however, which is why engineering makes use of tetrahedral trusses.[citation needed]

Triangulation

[edit]

Triangulation means the partition of any planar object into a collection of triangles. For example, in polygon triangulation, a polygon is subdivided into multiple triangles that are attached edge-to-edge, with the property that their vertices coincide with the set of vertices of the polygon.[54] In the case of a simple polygon with sides, there are triangles that are separated by diagonals. Triangulation of a simple polygon has a relationship to the ear, a vertex connected by two other vertices, the diagonal between which lies entirely within the polygon. The two ears theorem states that every simple polygon that is not itself a triangle has at least two ears.[55]

Location of a point

[edit]One way to identify locations of points in (or outside) a triangle is to place the triangle in an arbitrary location and orientation in the Cartesian plane, and to use Cartesian coordinates. While convenient for many purposes, this approach has the disadvantage of all points' coordinate values being dependent on the arbitrary placement in the plane.[56]

Two systems avoid that feature, so that the coordinates of a point are not affected by moving the triangle, rotating it, or reflecting it as in a mirror, any of which gives a congruent triangle, or even by rescaling it to a similar triangle:[57]

- Trilinear coordinates specify the relative distances of a point from the sides, so that coordinates indicate that the ratio of the distance of the point from the first side to its distance from the second side is , etc.

- Barycentric coordinates of the form specify the point's location by the relative weights that would have to be put on the three vertices in order to balance the otherwise weightless triangle on the given point.

Related figures

[edit]Figures inscribed in a triangle

[edit]As discussed above, every triangle has a unique inscribed circle (incircle) that is interior to the triangle and tangent to all three sides. Every triangle has a unique Steiner inellipse which is interior to the triangle and tangent at the midpoints of the sides. Marden's theorem shows how to find the foci of this ellipse.[58] This ellipse has the greatest area of any ellipse tangent to all three sides of the triangle. The Mandart inellipse of a triangle is the ellipse inscribed within the triangle tangent to its sides at the contact points of its excircles. For any ellipse inscribed in a triangle , let the foci be and , then:[59]

From an interior point in a reference triangle, the nearest points on the three sides serve as the vertices of the pedal triangle of that point. If the interior point is the circumcenter of the reference triangle, the vertices of the pedal triangle are the midpoints of the reference triangle's sides, and so the pedal triangle is called the midpoint triangle or medial triangle. The midpoint triangle subdivides the reference triangle into four congruent triangles which are similar to the reference triangle.[60]

The intouch triangle of a reference triangle has its vertices at the three points of tangency of the reference triangle's sides with its incircle.[61] The extouch triangle of a reference triangle has its vertices at the points of tangency of the reference triangle's excircles with its sides (not extended).[62]

The inscribed squares tangent their vertices to the triangle's sides is the special case of inscribed square problem, although the problem asking for a square whose vertices lie on a simple closed curve. A notable example of this figure relation is the Calabi triangle in which the vertices of every three squares are tangent to all obtuse triangle's sides. Every acute triangle has three inscribed squares (squares in its interior such that all four of a square's vertices lie on a side of the triangle, so two of them lie on the same side and hence one side of the square coincides with part of a side of the triangle). In a right triangle, two of the squares coincide and have a vertex at the triangle's right angle, so a right triangle has only two distinct inscribed squares. An obtuse triangle has only one inscribed square, with a side coinciding with part of the triangle's longest side. Within a given triangle, a longer common side is associated with a smaller inscribed square. If an inscribed square has a side of length and the triangle has a side of length , part of which side coincides with a side of the square, then , , from the side , and the triangle's area are related according to[63]The largest possible ratio of the area of the inscribed square to the area of the triangle is 1/2, which occurs when , , and the altitude of the triangle from the base of length is equal to . The smallest possible ratio of the side of one inscribed square to the side of another in the same non-obtuse triangle is .[64] Both of these extreme cases occur for the isosceles right triangle.[citation needed]

The Lemoine hexagon is a cyclic hexagon with vertices given by the six intersections of the sides of a triangle with the three lines that are parallel to the sides and that pass through its symmedian point. In either its simple form or its self-intersecting form, the Lemoine hexagon is interior to the triangle with two vertices on each side of the triangle.[citation needed]

Every convex polygon with area can be inscribed in a triangle of area at most equal to . Equality holds only if the polygon is a parallelogram.[65]

Figures circumscribed about a triangle

[edit]The tangential triangle of a reference triangle (other than a right triangle) is the triangle whose sides are on the tangent lines to the reference triangle's circumcircle at its vertices.[66]

As mentioned above, every triangle has a unique circumcircle, a circle passing through all three vertices, whose center is the intersection of the perpendicular bisectors of the triangle's sides. Furthermore, every triangle has a unique Steiner circumellipse, which passes through the triangle's vertices and has its center at the triangle's centroid. Of all ellipses going through the triangle's vertices, it has the smallest area.[67]

The Kiepert hyperbola is unique conic that passes through the triangle's three vertices, its centroid, and its circumcenter.[68]

Of all triangles contained in a given convex polygon, one with maximal area can be found in linear time; its vertices may be chosen as three of the vertices of the given polygon.[69]

Miscellaneous triangles

[edit]Circular triangles

[edit]

A circular triangle is a triangle with circular arc edges. The edges of a circular triangle may be either convex (bending outward) or concave (bending inward).[c] The intersection of three disks forms a circular triangle whose sides are all convex. An example of a circular triangle with three convex edges is a Reuleaux triangle, which can be made by intersecting three circles of equal size. The construction may be performed with a compass alone without needing a straightedge, by the Mohr–Mascheroni theorem. Alternatively, it can be constructed by rounding the sides of an equilateral triangle.[70]

A special case of concave circular triangle can be seen in a pseudotriangle.[71] A pseudotriangle is a simply-connected subset of the plane lying between three mutually tangent convex regions. These sides are three smoothed curved lines connecting their endpoints called the cusp points. Any pseudotriangle can be partitioned into many pseudotriangles with the boundaries of convex disks and bitangent lines, a process known as pseudo-triangulation. For disks in a pseudotriangle, the partition gives pseudotriangles and bitangent lines.[72] The convex hull of any pseudotriangle is a triangle.[73]

Triangle in non-planar space

[edit]A non-planar triangle is a triangle not embedded in a Euclidean space, roughly speaking a flat space. This means triangles may also be discovered in several spaces, as in hyperbolic space and spherical geometry. A triangle in hyperbolic space is called a hyperbolic triangle, and it can be obtained by drawing on a negatively curved surface, such as a saddle surface. Likewise, a triangle in spherical geometry is called a spherical triangle, and it can be obtained by drawing on a positively curved surface such as a sphere.[74]

The triangles in both spaces have properties different from the triangles in Euclidean space. For example, as mentioned above, the internal angles of a triangle in Euclidean space always add up to 180°. However, the sum of the internal angles of a hyperbolic triangle is less than 180°, and for any spherical triangle, the sum is more than 180°.[74] In particular, it is possible to draw a triangle on a sphere such that the measure of each of its internal angles equals 90°, adding up to a total of 270°. By Girard's theorem, the sum of the angles of a triangle on a sphere is , where is the fraction of the sphere's area enclosed by the triangle.[75][76]

In more general spaces, there are comparison theorems relating the properties of a triangle in the space to properties of a corresponding triangle in a model space like hyperbolic or elliptic space.[77] For example, a CAT(k) space is characterized by such comparisons.[78]

Fractal geometry

[edit]Fractal shapes based on triangles include the Sierpiński gasket and the Koch snowflake.[79]

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The definition by Euclid states that an isosceles triangle is a triangle with exactly two equal sides.[5] By the modern definition, it has at least two equal sides, implying that an equilateral triangle is a special case of isosceles triangle.[6]

- ^ Again, in all cases "mirror images" are also similar.

- ^ A subset of a plane is convex if, given any two points in that subset, the whole line segment joining them also lies within that subset.

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Lang & Murrow 1988, p. 4.

- ^ Byrne 2013, pp. xx–xxi.

- ^

- Lang & Murrow 1988, p. 4

- Heath 1926, Definition 20

- ^

- Lang & Murrow 1988, p. 4

- Ryan 2008, p. 91

- ^ Heath 1926, p. 187, Definition 20.

- ^ Stahl 2003, p. 37.

- ^

- Ryan 2008, p. 91

- Usiskin & Griffin 2008, p. 4

- ^

- Lang & Murrow 1988, p. 44

- Ryan 2008, p. 96

- ^ Heath 1926, Definition 20, Definition 21.

- ^

- ^ Herz-Fischler (2000).

- ^ Guillermo (2012), p. 161.

- ^ Cundy (1952).

- ^ Montroll (2009), p. 4.

- ^

- Lardner (1840), p. 46

- Montroll (2009), p. 6

- ^ Cromwell (1997), p. 341.

- ^ Holme 2010, p. 210.

- ^ Holme 2010, p. 143.

- ^ Lang & Murrow 1988, p. 126–127.

- ^ Lang & Murrow 1988, p. 128.

- ^ Anglin & Lambek 1995, p. 30.

- ^ Ryan 2008, p. 105.

- ^

- Lang & Murrow 1988, p. 84

- King 2021, p. 78

- ^ King 2021, p. 153.

- ^ Ryan 2008, p. 106.

- ^ Ryan 2008, p. 104.

- ^ a b King 2021, p. 155.

- ^ Schattschneider, Doris; King, James (1997). Geometry Turned On: Dynamic Software in Learning, Teaching, and Research. The Mathematical Association of America. pp. 3–4. ISBN 978-0883850992.

- ^ Edmonds, Allan L.; Hajja, Mowaffaq; Martini, Horst (2008). "Orthocentric simplices and biregularity". Results in Mathematics. 52 (1–2): 41–50. doi:10.1007/s00025-008-0294-4. MR 2430410.

It is well known that the incenter of a Euclidean triangle lies on its Euler line connecting the centroid and the circumcenter if and only if the triangle is isosceles.

- ^ Ryan 2008, p. 102.

- ^ Holme 2010, p. 240.

- ^ Heath 1926, Proposition 32.

- ^ Gonick 2024, pp. 107–109.

- ^ Ramsay & Richtmyer 1995, p. 38.

- ^ Gonick 2024, pp. 224–225.

- ^ Young 2017, p. 27.

- ^ Axler 2012, p. 634.

- ^ Richmond, Bettina; Richmond, Thomas (1997). "Metric spaces in which all triangles are degenerate". The American Mathematical Monthly. 104 (8): 713–719. doi:10.1080/00029890.1997.11990706. JSTOR 2975234. MR 1476755.

- ^ Alonso, Orlando Braulio (2009). Making sense of definitions in geometry: Metric-combinatorial approaches to classifying triangles and quadrilaterals (PhD thesis). Teachers College, Columbia University. p. 57. ProQuest 304870039.

- ^

- ^ Gonick 2024, pp. 157–167.

- ^ Gonick 2024, p. 167.

- ^ Gonick 2024, p. 171.

- ^ Gonick 2024, p. 64.

- ^ Gonick 2024, pp. 65, 72–73, 111.

- ^ Ryan 2008, p. 98.

- ^ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Heron of Alexandria", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- ^ Heath 1926, Propositions 36–41.

- ^ Braden, Bart (1986). "The Surveyor's Area Formula" (PDF). The College Mathematics Journal. 17 (4): 326–337. doi:10.2307/2686282. JSTOR 2686282. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 June 2014.

- ^

- Gonick 2024, p. 80

- Apostol 1997, p. 34–35

- ^ Smith 2000, p. 86–87.

- ^ Jordan & Smith 2010, p. 834.

- ^ Gonick 2024, p. 125.

- ^ Berg et al. 2000.

- ^ Meisters 1975.

- ^ Oldknow 1995.

- ^

- ^ Kalman 2008.

- ^ Allaire, Zhou & Yao 2012.

- ^ Coxeter & Greitzer 1967, pp. 18, 23–25.

- ^ Kimberling, Clark (March 2008). "Twenty-one points on the nine-point circle". The Mathematical Gazette. 92 (523): 29–38. doi:10.1017/S002555720018249X. ISSN 0025-5572.

- ^ Moses, Peter; Kimberling, Charles (2009). "Reflection-Induced Perspectivities Among Triangles" (PDF). Journal for Geometry and Graphics. 13 (1): 15–24.

- ^

- ^ Oxman & Stupel 2013.

- ^ Eggleston 2007, pp. 149–160.

- ^ Smith, Geoff; Leversha, Gerry (November 2007). "Euler and triangle geometry". Mathematical Gazette. 91 (522): 436–452. doi:10.1017/S0025557200182087. JSTOR 40378417.

- ^ Silvester, John R. (March 2017). "Extremal area ellipses of a convex quadrilateral". The Mathematical Gazette. 101 (550): 11–26. doi:10.1017/mag.2017.2.

- ^ Eddy, R. H.; Fritsch, R. (1994). "The Conics of Ludwig Kiepert: A Comprehensive Lesson in the Geometry of the Triangle". Mathematics Magazine. 67 (3): 188–205. doi:10.1080/0025570X.1994.11996212.

- ^ Chandran & Mount 1992.

- ^

- ^ Vahedi & van der Stappen 2008, p. 73.

- ^ Pocchiola & Vegter 1999, p. 259.

- ^ Devadoss & O'Rourke 2011, p. 93.

- ^ a b Nielsen 2021, p. 154.

- ^ Polking, John C. (25 April 1999). "The area of a spherical triangle. Girard's Theorem". Geometry of the Sphere. Retrieved 19 August 2024.

- ^ Wood, John. "LAS 100 — Freshman Seminar — Fall 1996: Reasoning with shape and quantity". Retrieved 19 August 2024.

- ^ Berger 2002, pp. 134–139.

- ^ Ballmann 1995, p. viii+112.

- ^ Frame, Michael; Urry, Amelia (21 June 2016). Fractal Worlds: Grown, Built, and Imagined. Yale University Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-300-22070-4.

Works cited

[edit]- Allaire, Patricia R.; Zhou, Junmin; Yao, Haishen (2012). "Proving a nineteenth century ellipse identity"". Mathematical Gazette. 96: 161–165. doi:10.1017/S0025557200004277.

- Anglin, W. S.; Lambek, J. (1995). The Heritage of Thales. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-0803-7. ISBN 978-1-4612-0803-7.

- Apostol, Tom M. (1997). Linear Algebra. Wiley. ISBN 0-471-17421-1.

- Axler, Sheldon (2012). Algebra and Trigonometry. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0470-58579-5.

- Bailey, Herbert; Detemple, Duane (1998). "Squares inscribed in angles and triangles". Mathematics Magazine. 71 (4): 278–284. doi:10.1080/0025570X.1998.11996652.

- Ballmann, Werner (1995). Lectures on spaces of nonpositive curvature. DMV Seminar 25. Basel: Birkhäuser Verlag. pp. viii+112. ISBN 3-7643-5242-6. MR 1377265.

- Berger, Marcel (2002). A panoramic view of Riemannian geometry. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-18245-7. ISBN 978-3-642-18245-7.

- Berg, Mark Theodoor de; Kreveld, Marc van; Overmars, Mark H.; Schwarzkopf, Otfried (2000). Computational geometry: algorithms and applications (2 ed.). Berlin Heidelberg: Springer. pp. 45–61. ISBN 978-3-540-65620-3.

- Byrne, Oliver (2013) [1847]. The First Six Books of the Elements of Euclid (facsimile ed.). TASCHEN GmbH. ISBN 978-3-8365-4471-9.

- Cromwell, Peter R. (1997). Polyhedra. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-55432-9.

- Cundy, H. Martyn (1952). "Deltahedra". Mathematical Gazette. 36 (318): 263–266. doi:10.2307/3608204. JSTOR 3608204.

- Eggleston, H. G. (2007) [1957]. Problems in Euclidean Space: Applications of Convexity. Dover Publications. pp. 149–160. ISBN 978-0-486-45846-5.

- Chandran, Sharat; Mount, David M. (1992). "A parallel algorithm for enclosed and enclosing triangles". International Journal of Computational Geometry & Applications. 2 (2): 191–214. doi:10.1142/S0218195992000123. MR 1168956.

- Coxeter, H. S. M.; Greitzer, S. L. (1967). Geometry Revisited. Anneli Lax New Mathematical Library. Vol. 19. Mathematical Association of America. ISBN 978-0-88385-619-2.

- Devadoss, Satyan L.; O'Rourke, Joseph (2011). Discrete and Computational Geometry. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-14553-2.

- Ericson, Christer (2005). Real-Time Collision Detection. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-55860-732-3.

- Guillermo, Artemio R. (2012). Historical Dictionary of the Philippines. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0810872462.

- Gonick, Larry (2024). The Cartoon Guide to Geometry. William Morrow. ISBN 978-0-06-315757-6.

- Hann, Michael (2014). Structure and Form in Design: Critical Ideas for Creative Practice. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-4725-8431-1.

- Heath, Thomas L. (1926). The Thirteen Books of Euclid's Elements. Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. hdl:2027/uva.x001426155. Dover reprint, 1956. SBN 486-60088-2.

- Herz-Fischler, Roger (2000). The Shape of the Great Pyramid. Wilfrid Laurier University Press. ISBN 0-88920-324-5.

- Holme, A. (2010). Geometry: Our Cultural Heritage. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-14441-7. ISBN 978-3-642-14441-7.

- Hungerbühler, Norbert (1994). "A short elementary proof of the Mohr-Mascheroni theorem". American Mathematical Monthly. 101 (8): 784–787. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.45.9902. doi:10.2307/2974536. JSTOR 2974536. MR 1299166.

- Jordan, D. W.; Smith, P. (2010). Mathematical Techniques: An Introduction for the Engineering, Physical, and Mathematical Sciences (4th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-928201-2.

- Kalman, Dan (2008). "An Elementary Proof of Marden's Theorem". American Mathematical Monthly. 115 (4): 330–338. doi:10.1080/00029890.2008.11920532.

- King, James R. (2021). Geometry Transformed: Euclidean Plane Geometry Based on Rigid Motions. American Mathematical Society. ISBN 9781470464431.

- Lang, Serge; Murrow, Gene (1988). Geometry: A High School Course (2nd ed.). Springer. doi:10.1007/978-1-4757-2022-8. ISBN 978-1-4757-2022-8.

- Lardner, Dionysius (1840). A Treatise on Geometry and Its Application in the Arts. The Cabinet Cyclopædia. London.

- Longuet-Higgins, Michael S. (2003). "On the ratio of the inradius to the circumradius of a triangle". Mathematical Gazette. 87: 119–120. doi:10.1017/S0025557200172249.

- Meisters, G. H. (1975). "Polygons have ears". The American Mathematical Monthly. 82 (6): 648–651. doi:10.2307/2319703. JSTOR 2319703. MR 0367792.

- Montroll, John (2009). Origami Polyhedra Design. A K Peters. ISBN 9781439871065.

- Nielsen, Frank (2021). "On Geodesic Triangles with Right Angles in a Dually Flat Space". In Nielsen, Frank (ed.). Progress in Information Geometry: Theory and Applications. Signals and Communication Technology. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-65459-7. ISBN 978-3-030-65458-0.

- Oldknow, Adrian (1995). "Computer Aided Research into Triangle Geometry". The Mathematical Gazette. 79 (485 =): 263–274. doi:10.2307/3618298. JSTOR 3618298.

- Oxman, Victor; Stupel, Moshe (2013). "Why Are the Side Lengths of the Squares Inscribed in a Triangle so Close to Each Other?". Forum Geometricorum. 13: 113–115.

- Pocchiola, Michel; Vegter, Gert (1999). "On Polygonal Covers". In Chazelle, Bernard; Goodman, Jacob E.; Pollack, Richard (eds.). Advances in Discrete and Computational Geometry: Proceedings of the 1996 AMS-IMS-SIAM Joint Summer Research Conference, Discrete and Computational Geometry—Ten Years Later, July 14-18, 1996, Mount Holyoke College. American Mathematical Soc. ISBN 978-0-8218-0674-6.

- Ramsay, Arlan; Richtmyer, Robert D. (1995). Introduction to Hyperbolic Geometry. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-1-4757-5585-5. ISBN 978-1-4757-5585-5.

- Riley, Michael W.; Cochran, David J.; Ballard, John L. (December 1982). "An Investigation of Preferred Shapes for Warning Labels". Human Factors: The Journal of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society. 24 (6): 737–742. doi:10.1177/001872088202400610. S2CID 109362577.

- Ryan, Mark (2008). Geometry For Dummies. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-08946-0.

- Smith, James T. (2000). Methods of Geometry. Wiley. ISBN 0-471-25183-6.

- Stahl, Saul (2003). Geometry from Euclid to Knots. Prentice-Hall. ISBN 0-13-032927-4.

- Usiskin, Zalman; Griffin, Jennifer (2008). The Classification of Quadrilaterals: A Study in Definition. Research in Mathematics Education. Information Age Publishing. ISBN 9781607526001.

- Vahedi, Mostafa; van der Stappen, A. Frank (2008). "Caging Polygons with Two and Three Fingers". In Akella, Srinivas; Amato, Nancy M.; Huang, Wesley; Mishra, Bud (eds.). Algorithmic Foundation of Robotics VII: Selected Contributions of the Seventh International Workshop on the Algorithmic Foundations of Robotics. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-68405-3. ISBN 978-3-540-68405-3.

- Verdiyan, Vardan; Salas, Daniel Campos (2007). "Simple trigonometric substitutions with broad results". Mathematical Reflections (6).

- Young, Cynthia (2017). Trigonometry (4th ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-119-32113-2.

External links

[edit]- Ivanov, A.B. (2001) [1994]. "Triangle". Encyclopedia of Mathematics. EMS Press.

- Clark Kimberling: Encyclopedia of triangle centers. Lists some 5200 interesting points associated with any triangle.