Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Common scold

View on Wikipedia

In the common law of crime in England and Wales, a common scold was a type of public nuisance—a troublesome and angry person who broke the public peace by habitually chastising, arguing, and quarrelling with their neighbours. Most punished for scolding were women, though men could be found to be scolds.

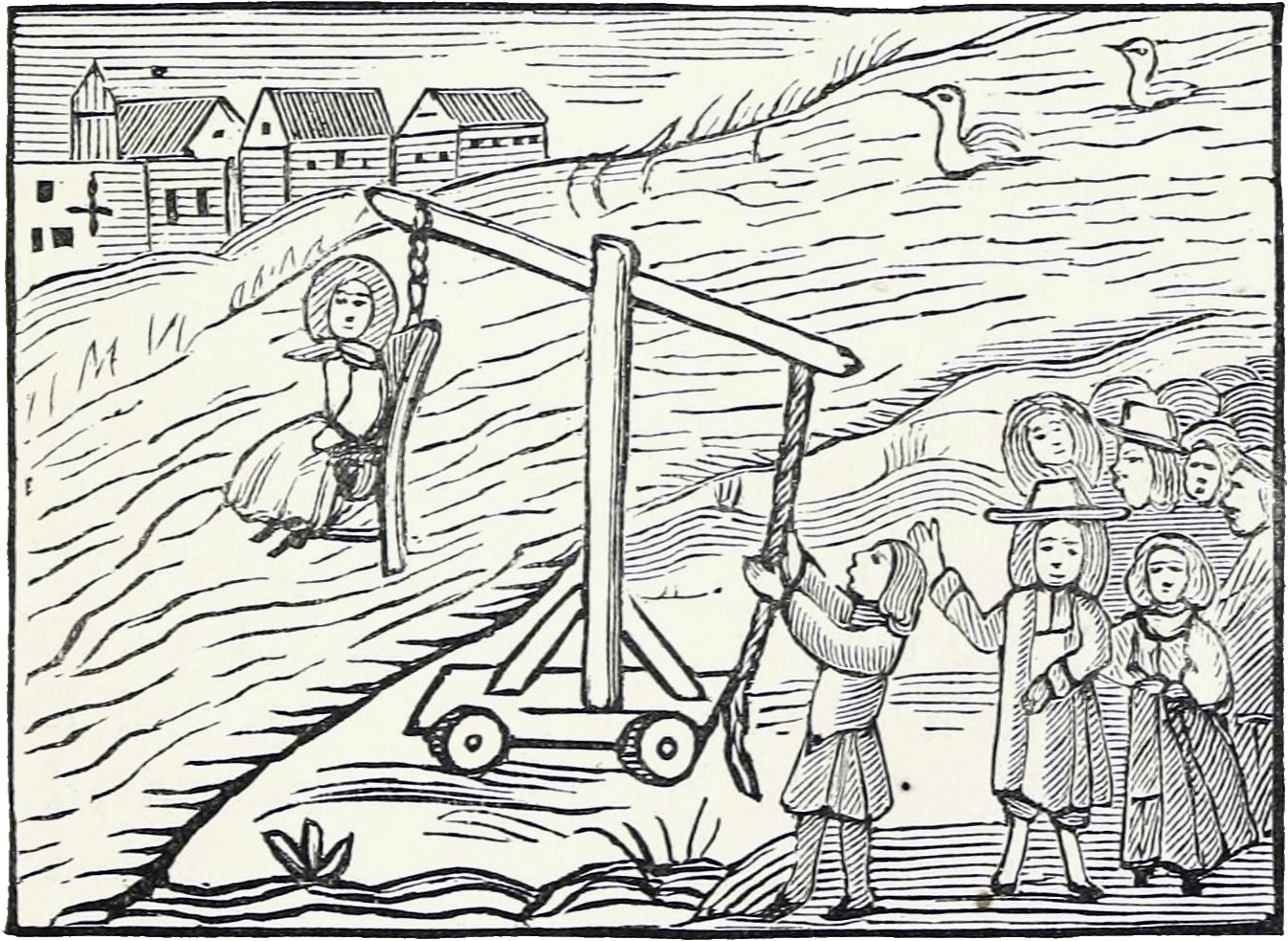

The offence, which carried across in the English colonisation of the Americas, was punished by fines and public humiliation: dunking (being arm-fastened into a chair and dunked into a river or pond); parading through the street; being put in the scold's bridle (branks) or the stocks. Selling bad bread or bad ale was also punished in these ways in some parts of England in medieval centuries.

None of the physical punishments is known to have been administered (such as by magistrates) since an instance in 1817 that involved a wheeling through the streets. Washington D.C. authorities imposed a fine against a writer against clerics, declared a common scold, in 1829. The offence and punishment were abolished in England and Wales in 1967, and formally in New Jersey in 1972.

The offence and its punishment

[edit]Medieval England

[edit]The offence of scolding developed from the late Middle Ages in England. A British historian suggests attempts to control and punish 'bad speech' increased after the Black Death, when demographic shift led to greater resistance and threats to the status quo.[1] This included prosecutions for scolding. Scolds were described using Latin terms, including objurgator, garulator, rixator and litigator, found in masculine and feminine forms (objurgatrix, etc.) in medieval legal records and all referring to negative forms of speech, chatter, quarrelling or reproachment. These offences were commonly presented and punished in manorial or borough courts that governed the behaviour of peasants and townspeople across England; with a scarce few to the parish vestry.[2] The most common punishment was a fine.

Some historians write of scolding and bad speech coded as feminine offences by the late medieval period. Women of all marital statuses were prosecuted for scolding. The married were featured most often, whereas widows were only rarely labelled scolds.[3] In places such as Exeter scolds were typically poorer women—elsewhere scolds could include members of the local elite.[4] Women who were also charged with matters such as violence, nightwandering, eavesdropping, flirting or adultery were also likely to be labelled scolds.[5] People were in some parts frequently labelled 'common scolds', indicating the impact of their behaviour and speech on a community. Karen Jones identified 13 men prosecuted for scolding in Kent's secular courts, compared to 94 women and 2 couples.[6]

Many of the male minority convicted were co-accused with their wives. In 1434, Helen Bradwall (wife of Peter Bradwall), scolded Hugh Welesson and his wife Isabel in Middlewich, calling Isabel a "child murderer" and Hugh a "skallet [wretched] knave". Isabel and Hugh also scolded Helen, calling her a "lesyng blebberer" (lying blatherer). All parties were fined for the offences—Hugh and Isabel: jointly.[7] Like women, male scolds were often accused of many other offences, such as fornication, theft, illegal trading, and assault.[8]

Later punishments of scolding

[edit]

Later legal treatises reflect the dominance of scolding as a charge levied against women. In the Commentaries on the Laws of England, Blackstone outlines the offence:

Lastly, a common scold, communis rixatrix, (for our law-latin confines it to the feminine gender) is a public nuisance to her neighbourhood. For which offence she may be indicted; and, if convicted, shall be sentenced to be placed in a certain engine of correction called the trebucket, castigatory, or cucking stool, which in the Saxon language signifies the scolding stool; though now it is frequently corrupted into ducking stool, because the residue of the judgment is, that, when she is so placed therein, she shall be plunged in the water for her punishment.

— Bl. Comm. IV:13.5.8, p. 169

This ascribes the shift to ducking stool to a folk etymology. Other writers disagree with this: the Domesday Book notes the use of a form of cucking stool at Chester as a cathedra stercoris, a "dung chair", whose punishment apparently involved exposing the sitter's buttocks to onlookers. This seat served to punish not only scolds, but also brewers and bakers who sold bad ale or bread, whereas the ducking stool dunked its victim into the water.

French traveller and writer Francois Maximilian Misson recorded the means used in England in the early 18th century:[10]

The way of punishing scolding women is pleasant enough. They fasten an armchair to the end of two beams twelve or fifteen feet long, and parallel to each other, so that these two pieces of wood with their two ends embrace the chair, which hangs between them by a sort of axle, by which means it plays freely, and always remains in the natural horizontal position in which a chair should be, that a person may sit conveniently in it, whether you raise it or let it down. They set up a post on the bank of a pond or river, and over this post they lay, almost in equilibrio, the two pieces of wood, at one end of which the chair hangs just over the water. They place the woman in this chair and so plunge her into the water as often as the sentence directs, in order to cool her immoderate heat.

The ducking stool, rather than being fixed by the water, could be mounted on wheels to allow the convict to be paraded through the streets before punishment was carried out. Another method of ducking was to use the tumbrel: a chair on two wheels with two long shafts fixed to joining axles. This would be pushed into the water and the shafts would be released, tipping the chair up backwards and ducking the occupant.[11]

A scold's bridle, known in Scotland as a brank, consists of a locking metal mask or head cage that contains a tab that fits in the mouth to inhibit talking. Some have claimed that convicted common scolds had to wear such a device as a preventive or punitive measure. Legal sources do not mention them in the context. Anecdotes report their use as a public punishment.[12][13]

In 17th-century New England and Long Island, scolds or those convicted of similar offences—men and women—could be sentenced to stand with their tongue in a cleft stick, a more primitive but easier-to-construct version of the bridle—alternatively, to the ducking stool.[14][10]

Prosecutions

[edit]

A plaque on the Fye Bridge in Norwich, England, claims to mark the site of a cucking stool, and that from 1562 to 1597 strumpets (flirtatious or promiscuous young women) and common scolds suffered dunking there. In the Percy Anecdotes, published pseudonymously by Thomas Byerley and Joseph Clinton Robertson in 1821–1823, the authors state that "How long the ducking-stool has been in disuse in England does not appear."[15] The Anecdotes also suggest penological ineffectiveness as grounds for the stool's disuse; the text relates the 1681 case of a Mrs. Finch, who had received three convictions and duckings as a common scold. On her fourth conviction, the King's Bench declined to dunk her again, ordering a fine of three marks and jail until payment took place.

The Percy Anecdotes also quote a pastoral poem by John Gay (1685–1732), who wrote that:

I'll speed me to the pond, where the high stool

On the long plank, hangs o'er the muddy pool,

That stool the dread of ev'ry scolding quean.[16]

and a 1780 poem by Benjamin West, who wrote that:

There stands, my friend, in yonder pool,

An engine call'd a ducking-stool;

By legal pow'r commanded down,

The joy and terror of the town.

If jarring females kindle strife ...[17]

While these literary sources do not prove that the punishment still took place, they do provide evidence that it had not been forgotten.

In The Queen v Foxby, 6 Mod. 11 (1704), counsel for the accused stated that he knew of no law for the dunking of scolds. Lord Chief Justice John Holt of the Queen's Bench apparently pronounced this error, for he announced that it was "better ducking in a Trinity, than a Michaelmas term", i.e. better carried out in summer than in winter. The tenor of Holt's remarks suggests that he found the punishment a rare or dead local custom seen by the sovereign's court as risible.[18]

The last recorded uses of ducking stool were

- a Mrs. Ganble at Plymouth (1808)

- Jenny Pipes, a "notorious" scold from Leominster (1809)

- Sarah Leeke (1817) from Leominster was sentenced to be ducked but the water in the pond was so low that the authorities merely wheeled her round the town in the chair.[11]

In 1812, federal enforcement of common law offences was held to be unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in United States v. Hudson and Goodwin. Nevertheless, in 1829, a Washington, D.C., court found the American anti-clerical writer Anne Royall guilty of being a common scold, the outcome of a campaign launched by local clergymen. A traditional "engine" for intended punishment was built by sailors at the Navy Yard. The court ruled the punishment of the ducking-stool obsolete and instead imposed a fine of ten dollars.[19]

Current status of the law

[edit]Counsel in Sykes v. Director of Public Prosecutions [1962] AC 528 said he could find no cases for more than a century and described the offence as "obsolete". Section 13(1)(a) of the Criminal Law Act 1967 abolished it.

The common law offence endured in New Jersey until struck down in 1972 in State v. Palendrano by Circuit Judge McGann, who found it had been subsumed in the provisions of the Disorderly Conduct Act of 1898, was bad for vagueness and offended the 14th Amendment to the US Constitution for sex discrimination. It was also opined that the punishment of ducking could amount to a corpor(e)al punishment, in which case that punishment was unlawful under the New Jersey Constitution of 1844 or since 1776.[20]

In the United States, many states have laws restricting public profanity, excessive noise, and disorderly conduct. None of these laws carry the distinctive punishment originally reserved for the common scold, nor are they gender-centric as the offence was.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Bardsley, Sandy (2006). "Sin, Speech and Scolding in Late Medieval England". Fama: The Politics of Talk and Reputation in Medieval Europe, ed. Thelma Fenster and Daniel Lord Smail: 146–48.

- ^ Jones, Karen (2006). Gender and petty crime in late medieval England : the local courts in Kent, 1460–1560. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. pp. 104–06. ISBN 184383216X. OCLC 65767599.

- ^ Bardsley, Sandy (2006). Venomous tongues : speech and gender in late medieval England. Philadelphia. pp. 123–25. ISBN 978-0812239362. OCLC 891396093.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Bardsley, Sandy (2006). Venomous tongues : speech and gender in late medieval England. Philadelphia. pp. 135–36. ISBN 978-0812239362. OCLC 891396093.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Bardsley, Sandy (2006). Venomous tongues : speech and gender in late medieval England. Philadelphia. p. 137. ISBN 978-0812239362. OCLC 891396093.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Jones, Karen (2006). Gender and petty crime in late medieval England : the local courts in Kent, 1460–1560. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. p. 108. ISBN 184383216X. OCLC 65767599.

- ^ Bardsley, Sandy (31 May 2006). Venomous tongues : speech and gender in late medieval England. Philadelphia. p. 102. ISBN 978-0812239362. OCLC 891396093.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Bardsley, Sandy (2006). Venomous tongues : speech and gender in late medieval England. Philadelphia. p. 103. ISBN 978-0812239362. OCLC 891396093.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Scold's bridle#Historical examples

- ^ a b Morse Earle, Alice (1896). "The Ducking Stool". Curious Punishments of Bygone Days. Archived from the original on 17 January 2007. Retrieved 18 January 2007.

- ^ a b Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 8 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 361.

- ^ Dugdale, Thomas; Burnett, William (1860). England and Wales Delineated: Historical, Entertaining & Commercial. n. pub. pp. 1238.

- ^ Fairholt, Frederick W. (1855). "On a Grotesque Mask of Punishment Obtained in the Castle of Nuremberg". Transactions of the Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire. VII. London: J.H. Parker for the Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire: 62–64.

- ^ Morse Earle, Alice (1896). "Branks and gags". Curious Punishments of Bygone Days. Archived from the original on 3 April 2007. Retrieved 18 January 2007.

- ^ Percy, Reuben; Percy, Sholto (1823). The Percy Anecdotes. London: Printed for T. Boys. Archived from the original on 10 September 2004.

- ^ Gay, John (1714). "The Shepherd's Week : Wednesday; or, The Dumps". Archived from the original on 1 November 2014. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

- ^ Morse Earle, Alice (1896). "Curious Punishments of Bygone Days". Project Gutenberg. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

- ^ "The Founders Constitution: Volume 5, Amendment VIII, Document 19". University of Chicago. 1987. Archived from the original on 12 March 2007. Retrieved 18 January 2007.

- ^ Earman, Cynthia (January 2001). "An Uncommon Scold". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 1 March 2019. Retrieved 18 January 2007.

- ^ State of New Jersey v. Marion Palendrano, 120 N.J. Super. 336 (1972) McCann JCC (Superior Court of New Jersey, Law Division (Criminal) 13 July 1972).

External links

[edit]- James v. Commonwealth, 12 Serg. & Rawle 220 (Penn., 1824). Judge Duncan rules the punishment of dunking a common scold obsolete and a cruel and unusual punishment.

Common scold

View on GrokipediaA common scold, known in Law Latin as communis rixatrix, was a category of public nuisance under English common law, specifically applied to women who habitually disturbed the neighborhood peace through quarrelsome, abusive, or scolding behavior.[1] This offence, rooted in Saxon traditions, targeted disruptions to social order rather than mere private disputes, positioning the scold as an offender against the community at large.[1] Conviction typically resulted in public humiliation via the cucking-stool—a device for exposure and sometimes immersion in water—or, in later practices, the branks, an iron gag and muzzle designed to silence the offender.[1] The gendered nature of the charge reflected prevailing views on female conduct, with punishments emphasizing restraint and degradation to deter repetition, though enforcement waned by the 19th century as common law evolved and such summary justice fell into desuetude.[2] Transmitted to American colonies, the practice exemplified early mechanisms for maintaining communal harmony through corporal correction, often without formal trial, highlighting tensions between individual expression and collective tranquility in pre-modern societies.[3]