Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Second inversion.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Second inversion

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

Not found

Second inversion

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia

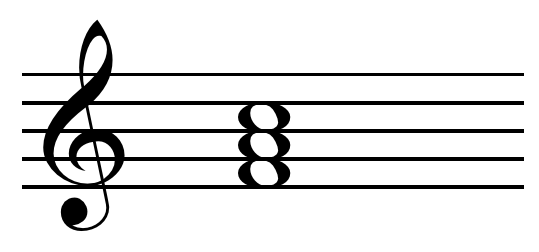

In music theory, second inversion refers to a specific voicing of a triad in which the fifth of the chord serves as the lowest note, or bass note, creating a configuration where the root and third appear above it.[1] This inversion distinguishes itself from root position (root in bass) and first inversion (third in bass) by altering the chord's intervallic structure, resulting in a sixth and a fourth above the bass note.[2] For example, a C major triad in second inversion places G in the bass, with C and E above, often notated in lead sheets as C/G.[1]

Second inversion triads, commonly symbolized in figured bass as ⁶₄, are generally considered less stable than their root or first inversion counterparts due to the dissonant fourth above the bass, which introduces a sense of tension.[3] In tonal harmony, they are used sparingly and with specific functions to enhance voice leading and melodic flow without disrupting the overall progression.[2] Key applications include cadential usage, where a dominant triad in second inversion (V⁶₄) precedes the tonic for emphatic resolution; passing bass motion, smoothing transitions between root-position chords; pedal or neighbor configurations, where the bass holds steady; and arpeggiated patterns within the same chord.[3]

In voice leading, second inversion triads typically double the bass note (the fifth) to maintain balance, though overuse is avoided to prevent harmonic ambiguity.[3] These chords appear across various musical styles but are particularly prominent in classical repertoire for their role in auxiliary sonorities and smooth bass lines.[2]

Fundamentals

Definition

In music theory, a second inversion occurs when the fifth of a chord is placed in the bass voice, with the root and third positioned above it, typically an octave higher than in root position.[1] This arrangement inverts the standard stacking of thirds in a chord, resulting in a voicing where the bass note supports the upper partials in a non-root configuration.[2] For instance, in a C major triad consisting of the notes C (root), E (third), and G (fifth), the second inversion positions G as the lowest note, followed by C and E above it, creating a compound interval structure from the bass: a perfect fourth from G to C and a major sixth from G to E.[1] This specific intervallic setup, often denoted in figured bass as 6/4, distinguishes second inversion from other chord positions.[2] Second inversion applies generally to both triads and extended chords, such as seventh chords, where the fifth remains in the bass while the root, third, and seventh are voiced above; this technique modifies the chord's voicing and bass line without altering its fundamental harmonic identity or function within a progression.[4][5] In terms of voice leading, the 6/4 interval structure inherent to second inversion introduces a dissonant perfect fourth above the bass, which contributes to a less stable sonority compared to root position, often requiring careful resolution to maintain harmonic coherence.[6]Comparison to Other Inversions

In root position, the root of the triad serves as the bass note, creating the most stable configuration by aligning the foundational pitch with the lowest register. First inversion places the third in the bass, resulting in a 6/3 voicing that facilitates smoother bass lines through stepwise motion while retaining moderate stability. Second inversion, by contrast, positions the fifth in the bass, forming a 6/4 structure that is generally perceived as less stable and more transitional due to the absence of the root or third in the lowest voice. Third inversion applies only to seventh chords, with the seventh in the bass (typically notated as 4/2),[7] introducing additional tension from the dissonant seventh interval above the bass. Functionally, second inversion chords exhibit relative weakness because the bass note—the fifth—does not strongly define the chord's harmonic identity, unlike the root or third, leading to their avoidance in positions requiring emphatic harmonic resolution, such as strong beats in cadences. Standard music theory pedagogy emphasizes this instability, treating second inversions as auxiliary or passing formations rather than primary harmonic pillars, in contrast to the grounding provided by root position or the connective role of first inversion. For seventh chords, third inversion amplifies this tension, often functioning as an unstable preparation for resolution due to the exposed seventh in the bass. Acoustically and perceptually, the placement of the fifth in the bass for second inversion creates a less grounded sound, as the harmonic series partials align more weakly with the fundamental frequency compared to root position, where the bass reinforces the chord's primary tone. Empirical studies confirm that listeners rate root-position chords highest in harmonic expectancy, with second inversions eliciting lower stability judgments than root or first inversions, though context can modulate this perception. This perceptual hierarchy stems from the bass's prominence in auditory processing, where non-root bass notes disrupt the expected alignment of overtones.| Inversion | Bass Note | Intervals Above Bass | Relative Stability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Root Position | Root | 3rd (to third), 5th (to fifth) | Most stable; establishes harmonic foundation.[2] |

| First Inversion | Third | 3rd (to fifth), 6th (to root) | Moderately stable; supports smooth voice leading.[1] |

| Second Inversion | Fifth | 4th (to root), 6th (to third) | Least stable for triads; transitional due to weak bass.[8] |

| Third Inversion (Seventh Chords Only) | Seventh | 2nd (to root), 4th (to third) | Tense and unstable; heightens dissonance.[7] |