Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Perception

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Psychology |

|---|

| Part of a series on |

| Philosophy |

|---|

| Neuropsychology |

|---|

|

Perception (from Latin perceptio 'gathering, receiving') is the organization, identification, and interpretation of sensory information in order to represent and understand the presented information or environment.[2] All perception involves signals that go through the nervous system, which in turn result from physical or chemical stimulation of the sensory system.[3] Vision involves light striking the retina of the eye; smell is mediated by odor molecules; and hearing involves pressure waves.

Perception is not only the passive receipt of these signals, but it is also shaped by the recipient's learning, memory, expectation, and attention.[4][5] Sensory input is a process that transforms this low-level information to higher-level information (e.g., extracts shapes for object recognition).[5] The following process connects a person's concepts and expectations (or knowledge) with restorative and selective mechanisms, such as attention, that influence perception.

Perception depends on complex functions of the nervous system, but subjectively seems mostly effortless because this processing happens outside conscious awareness.[3] Since the rise of experimental psychology in the 19th century, psychology's understanding of perception has progressed by combining a variety of techniques.[4] Psychophysics quantitatively describes the relationships between the physical qualities of the sensory input and perception.[6] Sensory neuroscience studies the neural mechanisms underlying perception. Perceptual systems can also be studied computationally, in terms of the information they process. Perceptual issues in philosophy include the extent to which sensory qualities such as sound, smell or color exist in objective reality rather than in the mind of the perceiver.[4]

Although people traditionally viewed the senses as passive receptors, the study of illusions and ambiguous images has demonstrated that the brain's perceptual systems actively and pre-consciously attempt to make sense of their input.[4] There is still active debate about the extent to which perception is an active process of hypothesis testing, analogous to science, or whether realistic sensory information is rich enough to make this process unnecessary.[4]

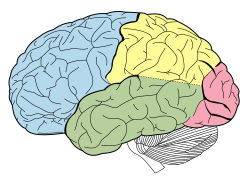

The perceptual systems of the brain enable individuals to see the world around them as stable, even though the sensory information is typically incomplete and rapidly varying. Human and other animal brains are structured in a modular way, with different areas processing different kinds of sensory information. Some of these modules take the form of sensory maps, mapping some aspect of the world across part of the brain's surface. These different modules are interconnected and influence each other. For instance, taste is strongly influenced by smell.[7]

Process and terminology

[edit]The process of perception begins with an object in the real world, known as the distal stimulus or distal object.[3] By means of light, sound, or another physical process, the object stimulates the body's sensory organs. These sensory organs transform the input energy into neural activity—a process called transduction.[3][8] This raw pattern of neural activity is called the proximal stimulus.[3] These neural signals are then transmitted to the brain and processed.[3] The resulting mental re-creation of the distal stimulus is the percept.

To explain the process of perception, an example could be an ordinary shoe. The shoe itself is the distal stimulus. When light from the shoe enters a person's eye and stimulates the retina, that stimulation is the proximal stimulus.[9] The image of the shoe reconstructed by the brain of the person is the percept. Another example could be a ringing telephone. The ringing of the phone is the distal stimulus. The sound stimulating a person's auditory receptors is the proximal stimulus. The brain's interpretation of this as the "ringing of a telephone" is the percept.

The different kinds of sensation (such as warmth, sound, and taste) are called sensory modalities or stimulus modalities.[8][10]

Bruner's model of the perceptual process

[edit]Psychologist Jerome Bruner developed a model of perception, in which people put "together the information contained in" a target and a situation to form "perceptions of ourselves and others based on social categories."[11][12] This model is composed of three states:

- When people encounter an unfamiliar target, they are very open to the informational cues contained in the target and the situation surrounding it.

- The first stage does not give people enough information on which to base perceptions of the target, so they will actively seek out cues to resolve this ambiguity. Gradually, people collect some familiar cues that enable them to make a rough categorization of the target.

- The cues become less open and selective. People try to search for more cues that confirm the categorization of the target. They actively ignore and distort cues that violate their initial perceptions. Their perception becomes more selective and they finally paint a consistent picture of the target.

Saks and John's three components to perception

[edit]According to Alan Saks and Gary Johns, there are three components to perception:[13][better source needed]

- The Perceiver: a person whose awareness is focused on the stimulus, and thus begins to perceive it. There are many factors that may influence the perceptions of the perceiver, while the three major ones include (1) motivational state, (2) emotional state, and (3) experience. All of these factors, especially the first two, greatly contribute to how the person perceives a situation. Oftentimes, the perceiver may employ what is called a "perceptual defense", where the person will only see what they want to see.

- The Target: the object of perception; something or someone who is being perceived. The amount of information gathered by the sensory organs of the perceiver affects the interpretation and understanding about the target.

- The Situation: the environmental factors, timing, and degree of stimulation that affect the process of perception. These factors may render a single stimulus to be left as merely a stimulus, not a percept that is subject for brain interpretation.

Multistable perception

[edit]Stimuli are not necessarily translated into a percept and rarely does a single stimulus translate into a percept. An ambiguous stimulus may sometimes be transduced into one or more percepts, experienced randomly, one at a time, in a process termed multistable perception. The same stimuli, or absence of them, may result in different percepts depending on subject's culture and previous experiences.[14]

Ambiguous figures demonstrate that a single stimulus can result in more than one percept. For example, the Rubin vase can be interpreted either as a vase or as two faces. The percept can bind sensations from multiple senses into a whole. A picture of a talking person on a television screen, for example, is bound to the sound of speech from speakers to form a percept of a talking person.

Types of perception

[edit]Vision

[edit]

In many ways, vision is the primary human sense. Light is taken in through each eye and focused in a way which sorts it on the retina according to direction of origin. A dense surface of photosensitive cells, including rods, cones, and intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells captures information about the intensity, color, and position of incoming light. Some processing of texture and movement occurs within the neurons on the retina before the information is sent to the brain. In total, about 15 differing types of information are then forwarded to the brain proper via the optic nerve.[15]

The timing of perception of a visual event, at points along the visual circuit, have been measured. A sudden alteration of light at a spot in the environment first alters photoreceptor cells in the retina, which send a signal to the retina bipolar cell layer which, in turn, can activate a retinal ganglion neuron cell. A retinal ganglion cell is a bridging neuron that connects visual retinal input to the visual processing centers within the central nervous system.[16] Light-altered neuron activation occurs within about 5–20 milliseconds in a rabbit retinal ganglion,[17] although in a mouse retinal ganglion cell the initial spike takes between 40 and 240 milliseconds before the initial activation.[18] The initial activation can be detected by an action potential spike, a sudden spike in neuron membrane electric voltage.

A perceptual visual event measured in humans was the presentation to individuals of an anomalous word. If these individuals are shown a sentence, presented as a sequence of single words on a computer screen, with a puzzling word out of place in the sequence, the perception of the puzzling word can register on an electroencephalogram (EEG). In an experiment, human readers wore an elastic cap with 64 embedded electrodes distributed over their scalp surface.[19] Within 230 milliseconds of encountering the anomalous word, the human readers generated an event-related electrical potential alteration of their EEG at the left occipital-temporal channel, over the left occipital lobe and temporal lobe.

Sound

[edit]

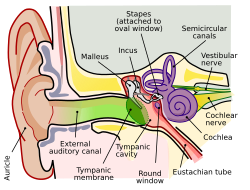

Hearing (or audition) is the ability to perceive sound by detecting vibrations (i.e., sonic detection). Frequencies capable of being heard by humans are called audio or audible frequencies, the range of which is typically considered to be between 20 Hz and 20,000 Hz.[20] Frequencies higher than audio are referred to as ultrasonic, while frequencies below audio are referred to as infrasonic.

The auditory system includes the outer ears, which collect and filter sound waves; the middle ear, which transforms the sound pressure (impedance matching); and the inner ear, which produces neural signals in response to the sound. By the ascending auditory pathway these are led to the primary auditory cortex within the temporal lobe of the human brain, from where the auditory information then goes to the cerebral cortex for further processing.

Sound does not usually come from a single source: in real situations, sounds from multiple sources and directions are superimposed as they arrive at the ears. Hearing involves the computationally complex task of separating out sources of interest, identifying them and often estimating their distance and direction.[21]

Touch

[edit]The process of recognizing objects through touch is known as haptic perception. It involves a combination of somatosensory perception of patterns on the skin surface (e.g., edges, curvature, and texture) and proprioception of hand position and conformation. People can rapidly and accurately identify three-dimensional objects by touch.[22] This involves exploratory procedures, such as moving the fingers over the outer surface of the object or holding the entire object in the hand.[23] Haptic perception relies on the forces experienced during touch.[24]

Professor Gibson defined the haptic system as "the sensibility of the individual to the world adjacent to his body by use of his body."[25] Gibson and others emphasized the close link between body movement and haptic perception, where the latter is active exploration.

The concept of haptic perception is related to the concept of extended physiological proprioception according to which, when using a tool such as a stick, perceptual experience is transparently transferred to the end of the tool.

Taste

[edit]Taste (formally known as gustation) is the ability to perceive the flavor of substances, including, but not limited to, food. Humans receive tastes through sensory organs concentrated on the upper surface of the tongue, called taste buds or gustatory calyculi.[26] The human tongue has 100 to 150 taste receptor cells on each of its roughly-ten thousand taste buds.[27]

Traditionally, there have been four primary tastes: sweetness, bitterness, sourness, and saltiness. The recognition and awareness of umami, which is considered the fifth primary taste, is a relatively recent development in Western cuisine.[28][29] Other tastes can be mimicked by combining these basic tastes,[27][30] all of which contribute only partially to the sensation and flavor of food in the mouth. Other factors include smell, which is detected by the olfactory epithelium of the nose;[7] texture, which is detected through a variety of mechanoreceptors, muscle nerves, etc.;[30][31] and temperature, which is detected by thermoreceptors.[30] All basic tastes are classified as either appetitive or aversive, depending upon whether the things they sense are harmful or beneficial.[32]

Smell

[edit]Smell is the process of absorbing molecules through olfactory organs, which are absorbed by humans through the nose. These molecules diffuse through a thick layer of mucus; come into contact with one of thousands of cilia that are projected from sensory neurons; and are then absorbed into a receptor (one of 347 or so).[33] It is this process that causes humans to understand the concept of smell from a physical standpoint.

Smell is also a very interactive sense as scientists have begun to observe that olfaction comes into contact with the other sense in unexpected ways.[34] It is also the most primal of the senses, as it is known to be the first indicator of safety or danger, therefore being the sense that drives the most basic of human survival skills. As such, it can be a catalyst for human behavior on a subconscious and instinctive level.[35]

Social

[edit]Social perception is the part of perception that allows people to understand the individuals and groups of their social world. Thus, it is an element of social cognition.[36]

Speech

[edit]

Speech perception is the process by which spoken language is heard, interpreted and understood. Research in this field seeks to understand how human listeners recognize the sound of speech (or phonetics) and use such information to understand spoken language.

Listeners manage to perceive words across a wide range of conditions, as the sound of a word can vary widely according to words that surround it and the tempo of the speech, as well as the physical characteristics, accent, tone, and mood of the speaker. Reverberation, signifying the persistence of sound after the sound is produced, can also have a considerable impact on perception. Experiments have shown that people automatically compensate for this effect when hearing speech.[21][37]

The process of perceiving speech begins at the level of the sound within the auditory signal and the process of audition. The initial auditory signal is compared with visual information—primarily lip movement—to extract acoustic cues and phonetic information. It is possible other sensory modalities are integrated at this stage as well.[38] This speech information can then be used for higher-level language processes, such as word recognition.

Speech perception is not necessarily uni-directional. Higher-level language processes connected with morphology, syntax, and/or semantics may also interact with basic speech perception processes to aid in recognition of speech sounds.[39] It may be the case that it is not necessary (maybe not even possible) for a listener to recognize phonemes before recognizing higher units, such as words. In an experiment, professor Richard M. Warren replaced one phoneme of a word with a cough-like sound. His subjects restored the missing speech sound perceptually without any difficulty. Moreover, they were not able to accurately identify which phoneme had even been disturbed.[40]

Faces

[edit]Facial perception refers to cognitive processes specialized in handling human faces (including perceiving the identity of an individual) and facial expressions (such as emotional cues.)[citation needed]

Social touch

[edit]The somatosensory cortex is a part of the brain that receives and encodes sensory information from receptors of the entire body.[41]

Affective touch is a type of sensory information that elicits an emotional reaction and is usually social in nature. Such information is actually coded differently than other sensory information. Though the intensity of affective touch is still encoded in the primary somatosensory cortex, the feeling of pleasantness associated with affective touch is activated more in the anterior cingulate cortex. Increased blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) contrast imaging, identified during functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), shows that signals in the anterior cingulate cortex, as well as the prefrontal cortex, are highly correlated with pleasantness scores of affective touch. Inhibitory transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) of the primary somatosensory cortex inhibits the perception of affective touch intensity, but not affective touch pleasantness. Therefore, the S1 is not directly involved in processing socially affective touch pleasantness, but still plays a role in discriminating touch location and intensity.[42]

Multi-modal perception

[edit]Multi-modal perception refers to concurrent stimulation in more than one sensory modality and the effect such has on the perception of events and objects in the world.[43]

Time (chronoception)

[edit]Chronoception refers to how the passage of time is perceived and experienced. Although the sense of time is not associated with a specific sensory system, the work of psychologists and neuroscientists indicates that human brains do have a system governing the perception of time,[44][45] composed of a highly distributed system involving the cerebral cortex, cerebellum, and basal ganglia. One particular component of the brain, the suprachiasmatic nucleus, is responsible for the circadian rhythm (commonly known as one's "internal clock"), while other cell clusters appear to be capable of shorter-range timekeeping, known as an ultradian rhythm.

One or more dopaminergic pathways in the central nervous system appear to have a strong modulatory influence on mental chronometry, particularly interval timing.[46]

Agency

[edit]Sense of agency refers to the subjective feeling of having chosen a particular action. Some conditions, such as schizophrenia, can cause a loss of this sense, which may lead a person into delusions, such as feeling like a machine or like an outside source is controlling them. An opposite extreme can also occur, where people experience everything in their environment as though they had decided that it would happen.[47]

Even in non-pathological cases, there is a measurable difference between the making of a decision and the feeling of agency. Through methods such as the Libet experiment, a gap of half a second or more can be detected from the time when there are detectable neurological signs of a decision having been made to the time when the subject actually becomes conscious of the decision.

There are also experiments in which an illusion of agency is induced in psychologically normal subjects. In 1999, psychologists Wegner and Wheatley gave subjects instructions to move a mouse around a scene and point to an image about once every thirty seconds. However, a second person—acting as a test subject but actually a confederate—had their hand on the mouse at the same time, and controlled some of the movement. Experimenters were able to arrange for subjects to perceive certain "forced stops" as if they were their own choice.[48][49]

Familiarity

[edit]Recognition memory is sometimes divided into two functions by neuroscientists: familiarity and recollection.[50] A strong sense of familiarity can occur without any recollection, for example in cases of deja vu.

The temporal lobe (specifically the perirhinal cortex) responds differently to stimuli that feel novel compared to stimuli that feel familiar. Firing rates in the perirhinal cortex are connected with the sense of familiarity in humans and other mammals. In tests, stimulating this area at 10–15 Hz caused animals to treat even novel images as familiar, and stimulation at 30–40 Hz caused novel images to be partially treated as familiar.[51] In particular, stimulation at 30–40 Hz led to animals looking at a familiar image for longer periods, as they would for an unfamiliar one, though it did not lead to the same exploration behavior normally associated with novelty.

Recent studies on lesions in the area concluded that rats with a damaged perirhinal cortex were still more interested in exploring when novel objects were present, but seemed unable to tell novel objects from familiar ones—they examined both equally. Thus, other brain regions are involved with noticing unfamiliarity, while the perirhinal cortex is needed to associate the feeling with a specific source.[52]

Sexual stimulation

[edit]Sexual stimulation is any stimulus (including bodily contact) that leads to, enhances, and maintains sexual arousal, possibly even leading to orgasm. Distinct from the general sense of touch, sexual stimulation is strongly tied to hormonal activity and chemical triggers in the body. Although sexual arousal may arise without physical stimulation, achieving orgasm usually requires physical sexual stimulation (stimulation of the Krause-Finger corpuscles[53] found in erogenous zones of the body.)

Other senses

[edit]Other senses enable perception of body balance (vestibular sense[54]); acceleration, including gravity; position of body parts (proprioception sense[1]). They can also enable perception of internal senses (interoception sense[55]), such as temperature, pain, suffocation, gag reflex, abdominal distension, fullness of rectum and urinary bladder, and sensations felt in the throat and lungs.

Reality

[edit]In the case of visual perception, some people can see the percept shift in their mind's eye.[56] Others, who are not picture thinkers, may not necessarily perceive the 'shape-shifting' as their world changes. This esemplastic nature has been demonstrated by an experiment that showed that ambiguous images have multiple interpretations on the perceptual level.

The confusing ambiguity of perception is exploited in human technologies such as camouflage and biological mimicry. For example, the wings of European peacock butterflies bear eyespots that birds respond to as though they were the eyes of a dangerous predator.

There is also evidence that the brain in some ways operates on a slight "delay" in order to allow nerve impulses from distant parts of the body to be integrated into simultaneous signals.[57]

Perception is one of the oldest fields in psychology. The oldest quantitative laws in psychology are Weber's law, which states that the smallest noticeable difference in stimulus intensity is proportional to the intensity of the reference; and Fechner's law, which quantifies the relationship between the intensity of the physical stimulus and its perceptual counterpart (e.g., testing how much darker a computer screen can get before the viewer actually notices). The study of perception gave rise to the Gestalt School of Psychology, with an emphasis on a holistic approach.

Physiology

[edit]A sensory system is a part of the nervous system responsible for processing sensory information. A sensory system consists of sensory receptors, neural pathways, and parts of the brain involved in sensory perception. Commonly recognized sensory systems are those for vision, hearing, somatic sensation (touch), taste and olfaction (smell), as listed above. It has been suggested that the immune system is an overlooked sensory modality.[58] In short, senses are transducers from the physical world to the realm of the mind.

The receptive field is the specific part of the world to which a receptor organ and receptor cells respond. For instance, the part of the world an eye can see, is its receptive field; the light that each rod or cone can see, is its receptive field.[59] Receptive fields have been identified for the visual system, auditory system and somatosensory system, so far. Research attention is currently focused not only on external perception processes, but also to "interoception", considered as the process of receiving, accessing and appraising internal bodily signals. Maintaining desired physiological states is critical for an organism's well-being and survival. Interoception is an iterative process, requiring the interplay between perception of body states and awareness of these states to generate proper self-regulation. Afferent sensory signals continuously interact with higher order cognitive representations of goals, history, and environment, shaping emotional experience and motivating regulatory behavior.[60]

Features

[edit]Constancy

[edit]Perceptual constancy is the ability of perceptual systems to recognize the same object from widely varying sensory inputs.[5]: 118–120 [61] For example, individual people can be recognized from views, such as frontal and profile, which form very different shapes on the retina. A coin looked at face-on makes a circular image on the retina, but when held at angle it makes an elliptical image.[21] In normal perception these are recognized as a single three-dimensional object. Without this correction process, an animal approaching from the distance would appear to gain in size.[62][63] One kind of perceptual constancy is color constancy: for example, a white piece of paper can be recognized as such under different colors and intensities of light.[63] Another example is roughness constancy: when a hand is drawn quickly across a surface, the touch nerves are stimulated more intensely. The brain compensates for this, so the speed of contact does not affect the perceived roughness.[63] Other constancies include melody, odor, brightness and words.[64] These constancies are not always total, but the variation in the percept is much less than the variation in the physical stimulus.[63] The perceptual systems of the brain achieve perceptual constancy in a variety of ways, each specialized for the kind of information being processed,[65] with phonemic restoration as a notable example from hearing.

Grouping (Gestalt)

[edit]

The principles of grouping (or Gestalt laws of grouping) are a set of principles in psychology, first proposed by Gestalt psychologists, to explain how humans naturally perceive objects with patterns and objects. Gestalt psychologists argued that these principles exist because the mind has an innate disposition to perceive patterns in the stimulus based on certain rules. These principles are organized into six categories:

- Proximity: the principle of proximity states that, all else being equal, perception tends to group stimuli that are close together as part of the same object, and stimuli that are far apart as two separate objects.

- Similarity: the principle of similarity states that, all else being equal, perception lends itself to seeing stimuli that physically resemble each other as part of the same object and that are different as part of a separate object. This allows for people to distinguish between adjacent and overlapping objects based on their visual texture and resemblance.

- Closure: the principle of closure refers to the mind's tendency to see complete figures or forms even if a picture is incomplete, partially hidden by other objects, or if part of the information needed to make a complete picture in our minds is missing. For example, if part of a shape's border is missing people still tend to see the shape as completely enclosed by the border and ignore the gaps.

- Good Continuation: the principle of good continuation makes sense of stimuli that overlap: when there is an intersection between two or more objects, people tend to perceive each as a single uninterrupted object.

- Common Fate: the principle of common fate groups stimuli together on the basis of their movement. When visual elements are seen moving in the same direction at the same rate, perception associates the movement as part of the same stimulus. This allows people to make out moving objects even when other details, such as color or outline, are obscured.

- The principle of good form refers to the tendency to group together forms of similar shape, pattern, color, etc.[66][67][68][69]

Later research has identified additional grouping principles.[70]

Contrast effects

[edit]A common finding across many different kinds of perception is that the perceived qualities of an object can be affected by the qualities of context. If one object is extreme on some dimension, then neighboring objects are perceived as further away from that extreme.

"Simultaneous contrast effect" is the term used when stimuli are presented at the same time, whereas successive contrast applies when stimuli are presented one after another.[71]

The contrast effect was noted by the 17th Century philosopher John Locke, who observed that lukewarm water can feel hot or cold depending on whether the hand touching it was previously in hot or cold water.[72] In the early 20th Century, Wilhelm Wundt identified contrast as a fundamental principle of perception, and since then the effect has been confirmed in many different areas.[72] These effects shape not only visual qualities like color and brightness, but other kinds of perception, including how heavy an object feels.[73] One experiment found that thinking of the name "Hitler" led to subjects rating a person as more hostile.[74] Whether a piece of music is perceived as good or bad can depend on whether the music heard before it was pleasant or unpleasant.[75] For the effect to work, the objects being compared need to be similar to each other: a television reporter can seem smaller when interviewing a tall basketball player, but not when standing next to a tall building.[73] In the brain, brightness contrast exerts effects on both neuronal firing rates and neuronal synchrony.[76]

Theories

[edit]Perception as direct perception (Gibson)

[edit]Cognitive theories of perception assume there is a poverty of the stimulus. This is the claim that sensations, by themselves, are unable to provide a unique description of the world.[77] Sensations require 'enriching', which is the role of the mental model.

The perceptual ecology approach was introduced by professor James J. Gibson, who rejected the assumption of a poverty of stimulus and the idea that perception is based upon sensations. Instead, Gibson investigated what information is actually presented to the perceptual systems. His theory "assumes the existence of stable, unbounded, and permanent stimulus-information in the ambient optic array. And it supposes that the visual system can explore and detect this information. The theory is information-based, not sensation-based."[78] He and the psychologists who work within this paradigm detailed how the world could be specified to a mobile, exploring organism via the lawful projection of information about the world into energy arrays.[79] "Specification" would be a 1:1 mapping of some aspect of the world into a perceptual array. Given such a mapping, no enrichment is required and perception is direct.[80]

Perception-in-action

[edit]From Gibson's early work derived an ecological understanding of perception known as perception-in-action, which argues that perception is a requisite property of animate action. It posits that, without perception, action would be unguided, and without action, perception would serve no purpose. Animate actions require both perception and motion, which can be described as "two sides of the same coin, the coin is action." Gibson works from the assumption that singular entities, which he calls invariants, already exist in the real world and that all that the perception process does is home in upon them.

The constructivist view, held by such philosophers as Ernst von Glasersfeld, regards the continual adjustment of perception and action to the external input as precisely what constitutes the "entity," which is therefore far from being invariant.[81] Glasersfeld considers an invariant as a target to be homed in upon, and a pragmatic necessity to allow an initial measure of understanding to be established prior to the updating that a statement aims to achieve. The invariant does not, and need not, represent an actuality. Glasersfeld describes it as extremely unlikely that what is desired or feared by an organism will never suffer change as time goes on. This social constructionist theory thus allows for a needful evolutionary adjustment.[82]

A mathematical theory of perception-in-action has been devised and investigated in many forms of controlled movement, and has been described in many different species of organism using the General Tau Theory. According to this theory, "tau information", or time-to-goal information is the fundamental percept in perception.

Evolutionary psychology

[edit]Many philosophers, such as Jerry Fodor, write that the purpose of perception is knowledge. However, evolutionary psychologists hold that the primary purpose of perception is to guide action.[83] They give the example of depth perception, which seems to have evolved not to aid in knowing the distances to other objects but rather to aid movement.[83] Evolutionary psychologists argue that animals ranging from fiddler crabs to humans use eyesight for collision avoidance, suggesting that vision is basically for directing action, not providing knowledge.[83] Neuropsychologists showed that perception systems evolved along the specifics of animals' activities. This explains why bats and worms can perceive different frequency of auditory and visual systems than, for example, humans.

Building and maintaining sense organs is metabolically expensive. More than half the brain is devoted to processing sensory information, and the brain itself consumes roughly one-fourth of one's metabolic resources. Thus, such organs evolve only when they provide exceptional benefits to an organism's fitness.[83]

Scientists who study perception and sensation have long understood the human senses as adaptations.[83] Depth perception consists of processing over half a dozen visual cues, each of which is based on a regularity of the physical world.[83] Vision evolved to respond to the narrow range of electromagnetic energy that is plentiful and that does not pass through objects.[83] Sound waves provide useful information about the sources of and distances to objects, with larger animals making and hearing lower-frequency sounds and smaller animals making and hearing higher-frequency sounds.[83] Taste and smell respond to chemicals in the environment that were significant for fitness in the environment of evolutionary adaptedness.[83] The sense of touch is actually many senses, including pressure, heat, cold, tickle, and pain.[83] Pain, while unpleasant, is adaptive.[83] An important adaptation for senses is range shifting, by which the organism becomes temporarily more or less sensitive to sensation.[83] For example, one's eyes automatically adjust to dim or bright ambient light.[83] Sensory abilities of different organisms often co-evolve, as is the case with the hearing of echolocating bats and that of the moths that have evolved to respond to the sounds that the bats make.[83]

Evolutionary psychologists claim that perception demonstrates the principle of modularity, with specialized mechanisms handling particular perception tasks.[83] For example, people with damage to a particular part of the brain are not able to recognize faces (prosopagnosia).[83] Evolutionary psychology suggests that this indicates a so-called face-reading module.[83]

Closed-loop perception

[edit]The theory of closed-loop perception proposes dynamic motor-sensory closed-loop process in which information flows through the environment and the brain in continuous loops.[84][85][86][87] Closed-loop perception appears consistent with anatomy and with the fact that perception is typically an incremental process. Repeated encounters with an object, whether conscious or not, enable an animal to refine its impressions of that object. This can be achieved more easily with a circular closed-loop system than with a linear open-loop one. Closed-loop perception can explain many of the phenomena that open-loop perception struggles to account for. This is largely because closed-loop perception considers motion to be an integral part of perception, and not an interfering component that must be corrected for. Furthermore, an environment perceived via sensor motion, and not despite sensor motion, need not be further stabilized by internal processes.[87]

Feature integration theory

[edit]Anne Treisman's feature integration theory (FIT) attempts to explain how characteristics of a stimulus such as physical location in space, motion, color, and shape are merged to form one percept despite each of these characteristics activating separate areas of the cortex. FIT explains this through a two part system of perception involving the preattentive and focused attention stages.[88][89][90][91][92]

The preattentive stage of perception is largely unconscious, and analyzes an object by breaking it down into its basic features, such as the specific color, geometric shape, motion, depth, individual lines, and many others.[88] Studies have shown that, when small groups of objects with different features (e.g., red triangle, blue circle) are briefly flashed in front of human participants, many individuals later report seeing shapes made up of the combined features of two different stimuli, thereby referred to as illusory conjunctions.[88][91]

The unconnected features described in the preattentive stage are combined into the objects one normally sees during the focused attention stage.[88] The focused attention stage is based heavily around the idea of attention in perception and 'binds' the features together onto specific objects at specific spatial locations (see the binding problem).[88][92]

Shared Intentionality theory

[edit]A fundamentally different approach to understanding the perception of objects relies upon the essential role of Shared intentionality.[93] Cognitive psychologist professor Michael Tomasello hypothesized that social bonds between children and caregivers would gradually increase through the essential motive force of shared intentionality beginning from birth.[94] The notion of shared intentionality, introduced by Michael Tomasello, was developed by later researchers, who tended to explain this collaborative interaction from different perspectives, e.g., psychophysiology,[95][96][97] and neurobiology.[98] The Shared intentionality approach considers perception occurrence at an earlier stage of organisms' development than other theories, even before the emergence of Intentionality. Because many theories build their knowledge about perception based on its main features of the organization, identification, and interpretation of sensory information to represent the holistic picture of the environment, Intentionality is the central issue in perception development. Nowadays, only one hypothesis attempts to explain Shared intentionality in all its integral complexity from the level of interpersonal dynamics to interaction at the neuronal level. Introduced by Latvian professor Igor Val Danilov, the hypothesis of neurobiological processes occurring during Shared intentionality[99] highlights that, at the beginning of cognition, very young organisms cannot distinguish relevant sensory stimuli independently. Because the environment is the cacophony of stimuli (electromagnetic waves, chemical interactions, and pressure fluctuations), their sensation is too limited by the noise to solve the cue problem. The relevant stimulus cannot overcome the noise magnitude if it passes through the senses. Therefore, Intentionality is a difficult problem for them since it needs the representation of the environment already categorized into objects (see also binding problem). The perception of objects is also problematic since it cannot appear without Intentionality. From the perspective of this hypothesis, Shared intentionality is collaborative interactions in which participants share the essential sensory stimulus of the actual cognitive problem. This social bond enables ecological training of the young immature organism, starting at the reflexes stage of development, for processing the organization, identification, and interpretation of sensory information in developing perception.[100] From this account perception emerges due to Shared intentionality in the embryonic stage of development, i.e., even before birth.[101]

Other theories of perception

[edit]Effects on perception

[edit]Effect of experience

[edit]With experience, organisms can learn to make finer perceptual distinctions, and learn new kinds of categorization. Wine-tasting, the reading of X-ray images and music appreciation are applications of this process in the human sphere. Research has focused on the relation of this to other kinds of learning, and whether it takes place in peripheral sensory systems or in the brain's processing of sense information.[102] Empirical research show that specific practices (such as yoga, mindfulness, Tai Chi, meditation, Daoshi and other mind-body disciplines) can modify human perceptual modality. Specifically, these practices enable perception skills to switch from the external (exteroceptive field) towards a higher ability to focus on internal signals (proprioception). Also, when asked to provide verticality judgments, highly self-transcendent yoga practitioners were significantly less influenced by a misleading visual context. Increasing self-transcendence may enable yoga practitioners to optimize verticality judgment tasks by relying more on internal (vestibular and proprioceptive) signals coming from their own body, rather than on exteroceptive, visual cues.[103]

Past actions and events that transpire right before an encounter or any form of stimulation have a strong degree of influence on how sensory stimuli are processed and perceived. On a basic level, the information our senses receive is often ambiguous and incomplete. However, they are grouped together in order for us to be able to understand the physical world around us. But it is these various forms of stimulation, combined with our previous knowledge and experience that allows us to create our overall perception. For example, when engaging in conversation, we attempt to understand their message and words by not only paying attention to what we hear through our ears but also from the previous shapes we have seen our mouths make. Another example would be if we had a similar topic come up in another conversation, we would use our previous knowledge to guess the direction the conversation is headed in.[104]

Effect of motivation and expectation

[edit]A perceptual set (also called perceptual expectancy or simply set) is a predisposition to perceive things in a certain way.[105] It is an example of how perception can be shaped by "top-down" processes such as drives and expectations.[106] Perceptual sets occur in all the different senses.[62] They can be long term, such as a special sensitivity to hearing one's own name in a crowded room, or short-term, as in the ease with which hungry people notice the smell of food.[107] A simple demonstration of the effect involved very brief presentations of non-words such as "sael". Subjects who were told to expect words about animals read it as "seal", but others who were expecting boat-related words read it as "sail".[107]

Sets can be created by motivation and so can result in people interpreting ambiguous figures so that they see what they want to see.[106] For instance, how someone perceives what unfolds during a sports game can be biased if they strongly support one of the teams.[108] In one experiment, students were allocated to pleasant or unpleasant tasks by a computer. They were told that either a number or a letter would flash on the screen to say whether they were going to taste an orange juice drink or an unpleasant-tasting health drink. In fact, an ambiguous figure was flashed on screen, which could either be read as the letter B or the number 13. When the letters were associated with the pleasant task, subjects were more likely to perceive a letter B, and when letters were associated with the unpleasant task they tended to perceive a number 13.[105]

Perceptual set has been demonstrated in many social contexts. When someone has a reputation for being funny, an audience is more likely to find them amusing.[107] Individual's perceptual sets reflect their own personality traits. For example, people with an aggressive personality are quicker to correctly identify aggressive words or situations.[107] In general, perceptual speed as a mental ability is positively correlated with personality traits such as conscientiousness, emotional stability, and agreeableness suggesting its evolutionary role in preserving homeostasis.[109]

One classic psychological experiment showed slower reaction times and less accurate answers when a deck of playing cards reversed the color of the suit symbol for some cards (e.g. red spades and black hearts).[110]

Philosopher Andy Clark explains that perception, although it occurs quickly, is not simply a bottom-up process (where minute details are put together to form larger wholes). Instead, our brains use what he calls predictive coding. It starts with very broad constraints and expectations for the state of the world, and as expectations are met, it makes more detailed predictions (errors lead to new predictions, or learning processes). Clark says this research has various implications; not only can there be no completely "unbiased, unfiltered" perception, but this means that there is a great deal of feedback between perception and expectation (perceptual experiences often shape our beliefs, but those perceptions were based on existing beliefs).[111] Indeed, predictive coding provides an account where this type of feedback assists in stabilizing our inference-making process about the physical world, such as with perceptual constancy examples.

Embodied cognition challenges the idea of perception as internal representations resulting from a passive reception of (incomplete) sensory inputs coming from the outside world. According to O'Regan (1992), the major issue with this perspective is that it leaves the subjective character of perception unexplained.[112] Thus, perception is understood as an active process conducted by perceiving and engaged agents (perceivers). Furthermore, perception is influenced by agents' motives and expectations, their bodily states, and the interaction between the agent's body and the environment around it.[113]

Philosophy

[edit]Perception is an important part of the theories of many philosophers it has been famously addressed by Rene Descartes, George Berkeley, and Immanuel Kant to name a few. In his work The Meditations Descartes begins by doubting all of his perceptions proving his existence with the famous phrase "I think therefore I am", and then works to the conclusion that perceptions are God-given.[114] George Berkely took the stance that all things that we see have a reality to them and that our perceptions were sufficient to know and understand that thing because our perceptions are capable of responding to a true reality.[115] Kant almost meets the rationalists and the empiricists half way. His theory utilizes the reality of a noumenon, the actual objects that cannot be understood, and then a phenomenon which is human understanding through the mind lens interpreting that noumenon.[116]

See also

[edit]- Action-specific perception

- Alice in Wonderland syndrome

- Apophenia

- Binding Problem

- Embodied cognition

- Change blindness

- Cognitive bias

- Cultural bias

- Experience model

- Feeling

- Generic views

- Ideasthesia

- Introspection

- Model-dependent realism

- Multisensory integration

- Near sets

- Neural correlates of consciousness

- Pareidolia

- Perceptual paradox

- Philosophy of perception

- Proprioception

- Qualia

- Recept

- Samjñā, the Buddhist concept of perception

- Shared intentionality

- Simulated reality

- Simulation

- Transsaccadic memory

- Visual routine

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b "Your 8 Senses". sensoryhealth.org. Retrieved 6 May 2024.

- ^ Schacter D (2011). Psychology. Worth Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4292-3719-2.

- ^ a b c d e f Goldstein (2009) pp. 5–7

- ^ a b c d e Gregory, Richard. "Perception" in Gregory, Zangwill (1987) pp. 598–601.

- ^ a b c Bernstein DA (5 March 2010). Essentials of Psychology. Cengage Learning. pp. 123–124. ISBN 978-0-495-90693-3. Archived from the original on 2 January 2017. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ^ Gustav Theodor Fechner. Elemente der Psychophysik. Leipzig 1860.

- ^ a b DeVere R, Calvert M (31 August 2010). Navigating Smell and Taste Disorders. Demos Medical Publishing. pp. 33–37. ISBN 978-1-932603-96-5. Archived from the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 26 March 2011.

- ^ a b Pomerantz, James R. (2003): "Perception: Overview". In: Lynn Nadel (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Cognitive Science, Vol. 3, London: Nature Publishing Group, pp. 527–537.

- ^ "Sensation and Perception". Archived from the original on 10 May 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- ^ Willis WD, Coggeshall RE (31 January 2004). Sensory Mechanisms of the Spinal Cord: Primary afferent neurons and the spinal dorsal horn. Springer. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-306-48033-1. Archived from the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ^ "Perception, Attribution, and, Judgment of Others" (PDF). Pearson Education. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- ^ Alan S. & Gary J. (2011). Perception, Attribution, and Judgment of Others. Organizational Behaviour: Understanding and Managing Life at Work, Vol. 7.

- ^ Sincero, Sarah Mae. 2013. "Perception." Explorable. Retrieved 8 March 2020 (https://explorable.com/perception).

- ^ Smith ER, Zárate MA (1992). "Exemplar-based model of social judgment". Psychological Review. 99 (1): 3–21. doi:10.1037/0033-295x.99.1.3. ISSN 0033-295X.

- ^ Gollisch T, Meister M (28 January 2010). "Eye Smarter than Scientists Believed: Neural Computations in Circuits of the Retina". Neuron. 65 (2): 150–164. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2009.12.009. PMC 3717333. PMID 20152123.

- ^ Kim US, Mahroo OA, Mollon JD, Yu-Wai-Man P (2021). "Retinal Ganglion Cells-Diversity of Cell Types and Clinical Relevance". Front Neurol. 12 661938. doi:10.3389/fneur.2021.661938. PMC 8175861. PMID 34093409.

- ^ Berry MJ, Warland DK, Meister M (May 1997). "The structure and precision of retinal spike trains". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 94 (10): 5411–6. Bibcode:1997PNAS...94.5411B. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.10.5411. PMC 24692. PMID 9144251.

- ^ Tengölics ÁJ, Szarka G, Ganczer A, Szabó-Meleg E, Nyitrai M, Kovács-Öller T, Völgyi B (October 2019). "Response Latency Tuning by Retinal Circuits Modulates Signal Efficiency". Sci Rep. 9 (1) 15110. Bibcode:2019NatSR...915110T. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-51756-y. PMC 6806000. PMID 31641196.

- ^ Kim AE, Gilley PM (2013). "Neural mechanisms of rapid sensitivity to syntactic anomaly". Front Psychol. 4: 45. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00045. PMC 3600774. PMID 23515395.

- ^ D'Ambrose C, Choudhary R (2003). Elert G (ed.). "Frequency range of human hearing". The Physics Factbook. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- ^ a b c Moore BC (15 October 2009). "Audition". In Goldstein EB (ed.). Encyclopedia of Perception. Sage. pp. 136–137. ISBN 978-1-4129-4081-8. Archived from the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 26 March 2011.

- ^ Klatzky RL, Lederman SJ, Metzger VA (1985). "Identifying objects by touch: An "expert system."". Perception & Psychophysics. 37 (4): 299–302. doi:10.3758/BF03211351. PMID 4034346.

- ^ Lederman SJ, Klatzky RL (1987). "Hand movements: A window into haptic object recognition". Cognitive Psychology. 19 (3): 342–368. doi:10.1016/0010-0285(87)90008-9. PMID 3608405. S2CID 3157751.

- ^ Robles-de-la-torre G, Hayward V (2001). "Force can overcome object geometry in the perception of shape through active touch". Nature. 412 (6845): 445–448. Bibcode:2001Natur.412..445R. doi:10.1038/35086588. PMID 11473320. S2CID 4413295.

- ^ Gibson J (1966). The senses considered as perceptual systems. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-313-23961-8.

- ^ Human biology (Page 201/464) Archived 2 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine Daniel D. Chiras. Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2005.

- ^ a b DeVere R, Calvert M (31 August 2010). Navigating Smell and Taste Disorders. Demos Medical Publishing. pp. 39–40. ISBN 978-1-932603-96-5. Archived from the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 26 March 2011.

- ^ "Umami Dearest: The mysterious fifth taste has officially infiltrated the food scene". trendcentral.com. 23 February 2010. Archived from the original on 18 April 2011. Retrieved 26 March 2011.

- ^ "#8 Food Trend for 2010: I Want My Umami". foodchannel.com. 6 December 2009. Archived from the original on 11 July 2011.

- ^ a b c Siegel GJ, Albers RW (2006). Basic neurochemistry: molecular, cellular, and medical aspects. Academic Press. p. 825. ISBN 978-0-12-088397-4. Archived from the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 26 March 2011.

- ^ Food texture: measurement and perception (page 3–4/311) Archived 2 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine Andrew J. Rosenthal. Springer, 1999.

- ^ Why do two great tastes sometimes not taste great together? Archived 28 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine scientificamerican.com. Dr. Tim Jacob, Cardiff University. 22 May 2009.

- ^ Brookes J (13 August 2010). "Science is perception: what can our sense of smell tell us about ourselves and the world around us?". Philosophical Transactions. Series A, Mathematical, Physical, and Engineering Sciences. 368 (1924): 3491–3502. Bibcode:2010RSPTA.368.3491B. doi:10.1098/rsta.2010.0117. PMC 2944383. PMID 20603363.

- ^ Weir K (February 2011). "Scents and sensibility". American Psychological Association. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

- ^ Bergland C (29 June 2015). "Psychology Today". How Does Scent Drive Human Behavior?.

- ^ E. R. Smith, D. M. Mackie (2000). Social Psychology. Psychology Press, 2nd ed., p. 20

- ^ Watkins AJ, Raimond A, Makin SJ (23 March 2010). "Room reflection and constancy in speech-like sounds: Within-band effects". In Lopez-Poveda EA (ed.). The Neurophysiological Bases of Auditory Perception. Springer. p. 440. Bibcode:2010nbap.book.....L. ISBN 978-1-4419-5685-9. Archived from the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 26 March 2011.

- ^ Rosenblum LD (15 April 2008). "Primacy of Multimodal Speech Perception". In Pisoni D, Remez R (eds.). The Handbook of Speech Perception. John Wiley & Sons. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-470-75677-5.

- ^ Davis MH, Johnsrude IS (July 2007). "Hearing speech sounds: Top-down influences on the interface between audition and speech perception". Hearing Research. 229 (1–2): 132–147. doi:10.1016/j.heares.2007.01.014. PMID 17317056. S2CID 12111361.

- ^ Warren RM (1970). "Restoration of missing speech sounds". Science. 167 (3917): 392–393. Bibcode:1970Sci...167..392W. doi:10.1126/science.167.3917.392. PMID 5409744. S2CID 30356740.

- ^ "Somatosensory Cortex". The Human Memory. 31 October 2019. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- ^ Case LK, Laubacher CM, Olausson H, Wang B, Spagnolo PA, Bushnell MC (2016). "Encoding of Touch Intensity But Not Pleasantness in Human Primary Somatosensory Cortex". J Neurosci. 36 (21): 5850–60. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1130-15.2016. PMC 4879201. PMID 27225773.

- ^ "Multi-Modal Perception". Lumen Waymaker. p. Introduction to Psychology. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- ^ Rao SM, Mayer AR, Harrington DL (March 2001). "The evolution of brain activation during temporal processing". Nature Neuroscience. 4 (3): 317–23. doi:10.1038/85191. PMID 11224550. S2CID 3570715.

- ^ "Brain Areas Critical To Human Time Sense Identified". UniSci – Daily University Science News. 27 February 2001.

- ^ Parker KL, Lamichhane D, Caetano MS, Narayanan NS (October 2013). "Executive dysfunction in Parkinson's disease and timing deficits". Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience. 7: 75. doi:10.3389/fnint.2013.00075. PMC 3813949. PMID 24198770.

Manipulations of dopaminergic signaling profoundly influence interval timing, leading to the hypothesis that dopamine influences internal pacemaker, or "clock", activity. For instance, amphetamine, which increases concentrations of dopamine at the synaptic cleft advances the start of responding during interval timing, whereas antagonists of D2 type dopamine receptors typically slow timing;... Depletion of dopamine in healthy volunteers impairs timing, while amphetamine releases synaptic dopamine and speeds up timing.

- ^ Metzinger T (2009). The Ego Tunnel. Basic Books. pp. 117–118. ISBN 978-0-465-04567-9.

- ^ Wegner DM, Wheatley T (July 1999). "Apparent mental causation. Sources of the experience of will". The American Psychologist. 54 (7): 480–92. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.188.8271. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.54.7.480. PMID 10424155.

- ^ Metzinger T (2003). Being No One. p. 508.

- ^ Mandler (1980). "Recognizing: the judgement of prior occurrence". Psychological Review. 87 (3): 252–271. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.87.3.252. S2CID 2166238.

- ^ Ho JW, Poeta DL, Jacobson TK, Zolnik TA, Neske GT, Connors BW, Burwell RD (September 2015). "Bidirectional Modulation of Recognition Memory". The Journal of Neuroscience. 35 (39): 13323–35. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2278-15.2015. PMC 4588607. PMID 26424881.

- ^ Kinnavane L, Amin E, Olarte-Sánchez CM, Aggleton JP (November 2016). "Detecting and discriminating novel objects: The impact of perirhinal cortex disconnection on hippocampal activity patterns". Hippocampus. 26 (11): 1393–1413. doi:10.1002/hipo.22615. PMC 5082501. PMID 27398938.

- ^ Themes UF (29 March 2017). "Sensory Corpuscles". Abdominal Key. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ^ "Your 8 Senses". sensoryhealth.org. Retrieved 6 May 2024.

- ^ "Your 8 Senses". sensoryhealth.org. Retrieved 6 May 2024.

- ^ Wettlaufer AK (2003). In the mind's eye : the visual impulse in Diderot, Baudelaire and Ruskin, pg. 257. Amsterdam: Rodopi. ISBN 978-90-420-1035-2.

- ^ The Secret Advantage Of Being Short Archived 21 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine by Robert Krulwich. All Things Considered, NPR. 18 May 2009.

- ^ Bedford FL (2011). "The missing sensory modality: the immune system". Perception. 40 (10): 1265–1267. doi:10.1068/p7119. PMID 22308900. S2CID 9546850.

- ^ Kolb & Whishaw: Fundamentals of Human Neuropsychology (2003)

- ^ Farb N., Daubenmier J., Price C. J., Gard T., Kerr C., Dunn B. D., Mehling W. E. (2015). "Interoception, contemplative practice, and health". Frontiers in Psychology. 6: 763. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00763. PMC 4460802. PMID 26106345.

- ^ Atkinson RL, Atkinson RC, Smith EE (March 1990). Introduction to psychology. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. pp. 177–183. ISBN 978-0-15-543689-3. Archived from the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- ^ a b Sonderegger T (16 October 1998). Psychology. John Wiley and Sons. pp. 43–46. ISBN 978-0-8220-5327-9. Archived from the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- ^ a b c d Goldstein EB (15 October 2009). "Constancy". In Goldstein EB (ed.). Encyclopedia of Perception. Sage. pp. 309–313. ISBN 978-1-4129-4081-8. Archived from the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 26 March 2011.

- ^ Roeckelein JE (2006). Elsevier's dictionary of psychological theories. Elsevier. p. 126. ISBN 978-0-444-51750-0. Archived from the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- ^ Yantis S (2001). Visual perception: essential readings. Psychology Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-86377-598-7. Archived from the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- ^ Gray, Peter O. (2006): Psychology, 5th ed., New York: Worth, p. 281. ISBN 978-0-7167-0617-5

- ^ Wolfe JM, Kluender KR, Levi DM, Bartoshuk LM, Herz RS, Klatzky RL, Lederman SJ (2008). "Gestalt Grouping Principles". Sensation and Perception (2nd ed.). Sinauer Associates. pp. 78, 80. ISBN 978-0-87893-938-1. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011.

- ^ Goldstein (2009). pp. 105–107

- ^ Banerjee JC (1994). "Gestalt Theory of Perception". Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Psychological Terms. M.D. Publications Pvt. Ltd. pp. 107–108. ISBN 978-81-85880-28-0.

- ^ Weiten W (1998). Psychology: themes and variations (4th ed.). Brooks/Cole Pub. Co. p. 144. ISBN 978-0-534-34014-8.

- ^ Corsini RJ (2002). The dictionary of psychology. Psychology Press. p. 219. ISBN 978-1-58391-328-4. Archived from the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- ^ a b Kushner LH (2008). Contrast in judgments of mental health. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-549-91314-6. Archived from the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- ^ a b Plous S (1993). The psychology of judgment and decision making. McGraw-Hill. pp. 38–41. ISBN 978-0-07-050477-6. Archived from the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- ^ Moskowitz GB (2005). Social cognition: understanding self and others. Guilford Press. p. 421. ISBN 978-1-59385-085-2. Archived from the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- ^ Popper AN (30 November 2010). Music Perception. Springer. p. 150. ISBN 978-1-4419-6113-6. Archived from the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- ^ Biederlack J, Castelo-Branco M, Neuenschwander S, Wheeler D, Singer W, Nikolić D (2006). "Brightness induction: Rate enhancement and neuronal synchronization as complementary codes". Neuron. 52 (6): 1073–1083. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2006.11.012. PMID 17178409. S2CID 16732916.

- ^ Stone, James V. (2012): "Vision and Brain: How we perceive the world", Cambridge, MIT Press, pp. 155–178.

- ^ Gibson, James J. (2002): "A Theory of Direct Visual Perception". In: Alva Noë/Evan Thompson (Eds.), Vision and Mind. Selected Readings in the Philosophy of Perception, Cambridge, MIT Press, pp. 77–89.

- ^ Sokolowski R (2008). Phenomenology of the Human Person. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 199–200. ISBN 978-0-521-71766-3. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015.

- ^ Richards RJ (December 1976). "James Gibson's Passive Theory of Perception: A Rejection of the Doctrine of Specific Nerve Energies" (PDF). Philosophy and Phenomenological Research. 37 (2): 218–233. doi:10.2307/2107193. JSTOR 2107193. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 June 2013.

- ^ Consciousness in Action, S. L. Hurley, illustrated, Harvard University Press, 2002, 0674007964, pp. 430–432.

- ^ Glasersfeld, Ernst von (1995), Radical Constructivism: A Way of Knowing and Learning, London: RoutledgeFalmer; Poerksen, Bernhard (ed.) (2004), The Certainty of Uncertainty: Dialogues Introducing Constructivism, Exeter: Imprint Academic; Wright. Edmond (2005). Narrative, Perception, Language, and Faith, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Gaulin, Steven J. C. and Donald H. McBurney. Evolutionary Psychology. Prentice Hall. 2003. ISBN 978-0-13-111529-3, Chapter 4, pp. 81–101.

- ^ Dewey J (1896). "The reflex arc concept in psychology" (PDF). Psychological Review. 3 (4): 359–370. doi:10.1037/h0070405. S2CID 14028152. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 November 2018.

- ^ Friston, K. (2010) The free-energy principle: a unified brain theory? Archived 8 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine nature reviews neuroscience 11:127-38

- ^ Tishby, N. and D. Polani, Information theory of decisions and actions, in Perception-Action Cycle. 2011, Springer. p. 601–636.

- ^ a b Ahissar E., Assa E. (2016). "Perception as a closed-loop convergence process". eLife. 5 e12830. doi:10.7554/eLife.12830. PMC 4913359. PMID 27159238.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

- ^ a b c d e Goldstein EB (2015). Cognitive Psychology: Connecting Mind, Research, and Everyday Experience, 4th Edition. Stamford, CT: Cengage Learning. pp. 109–112. ISBN 978-1-285-76388-0.

- ^ Treisman A, Gelade G (1980). "A Feature-Integration Theory of Attention" (PDF). Cognitive Psychology. 12 (1): 97–136. doi:10.1016/0010-0285(80)90005-5. PMID 7351125. S2CID 353246. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 September 2008 – via Science Direct.

- ^ Goldstein EB (2010). Sensation and Perception (8th ed.). Belmont, CA: Cengage Learning. pp. 144–146. ISBN 978-0-495-60149-4.

- ^ a b Treisman A, Schmidt H (1982). "Illusory Conjunctions in the Perception of Objects". Cognitive Psychology. 14 (1): 107–141. doi:10.1016/0010-0285(82)90006-8. PMID 7053925. S2CID 11201516 – via Science Direct.

- ^ a b Treisman A (1977). "Focused Attention in The Perception and Retrieval of Multidimensional Stimuli". Cognitive Psychology. 14 (1): 107–141. doi:10.1016/0010-0285(82)90006-8. PMID 7053925. S2CID 11201516 – via Science Direct.

- ^ Tomasello, M. (1999). The Cultural Origins of Human Cognition. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. 1999.

- ^ Tomasello, M. (2019). Becoming Human: A Theory of Ontogeny. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- ^ Val Danilov, I. & Mihailova, S. (2023). "Empirical Evidence of Shared Intentionality: Towards Bioengineering Systems Development." OBM Neurobiology 2023; 7(2): 167; doi:10.21926/obm.neurobiol.2302167. https://www.lidsen.com/journals/neurobiology/neurobiology-07-02-167

- ^ McClung, J. S., Placì, S., Bangerter, A., Clément, F., & Bshary, R. (2017). "The language of cooperation: shared intentionality drives variation in helping as a function of group membership." Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 284(1863), 20171682. http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2017.1682.

- ^ Shteynberg, G., & Galinsky, A. D. (2011). "Implicit coordination: Sharing goals with similar others intensifies goal pursuit." Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47(6), 1291-1294., https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp. 2011.04.012.

- ^ Fishburn, F. A., Murty, V. P., Hlutkowsky, C. O., MacGillivray, C. E., Bemis, L. M., Murphy, M. E., ... & Perlman, S. B. (2018). "Putting our heads together: interpersonal neural synchronization as a biological mechanism for shared intentionality." Social cognitive and affective neuroscience, 13(8), 841-849.

- ^ Val Danilov I (17 February 2023). "Theoretical Grounds of Shared Intentionality for Neuroscience in Developing Bioengineering Systems". OBM Neurobiology. 7 (1): 156. doi:10.21926/obm.neurobiol.2301156.

- ^ Val Danilov I (2023). "Shared Intentionality Modulation at the Cell Level: Low-Frequency Oscillations for Temporal Coordination in Bioengineering Systems". OBM Neurobiology. 7 (4): 1–17. doi:10.21926/obm.neurobiol.2304185.

- ^ Val Danilov I (2023). "Low-Frequency Oscillations for Nonlocal Neuronal Coupling in Shared Intentionality Before and After Birth: Toward the Origin of Perception". OBM Neurobiology. 7 (4): 1–17. doi:10.21926/obm.neurobiol.2304192.

- ^ Sumner M, Samuel AG (May 2009). "The Effect of Experience on the Perception and Representation of Dialect Variants" (PDF). Journal of Memory and Language. 60 (4). Elsevier Inc.: 487–501. doi:10.1016/j.jml.2009.01.001. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 February 2016. Retrieved 3 June 2015.

- ^ Fiori F, David N, Aglioti SM (2014). "Processing of proprioceptive and vestibular body signals and self-transcendence in Ashtanga yoga practitioners". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 8: 734. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2014.00734. PMC 4166896. PMID 25278866.

- ^ Snyder J (31 October 2015). "How previous experience shapes perception in different sensory modalities". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 9: 594. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2015.00594. PMC 4628108. PMID 26582982.

- ^ a b Weiten W (17 December 2008). Psychology: Themes and Variations. Cengage Learning. p. 193. ISBN 978-0-495-60197-5. Archived from the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- ^ a b Coon D, Mitterer JO (29 December 2008). Introduction to Psychology: Gateways to Mind and Behavior. Cengage Learning. pp. 171–172. ISBN 978-0-495-59911-1. Archived from the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- ^ a b c d Hardy M, Heyes S (2 December 1999). Beginning Psychology. Oxford University Press. pp. 24–27. ISBN 978-0-19-832821-6. Archived from the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- ^ Block JR, Yuker HE (1 October 2002). Can You Believe Your Eyes?: Over 250 Illusions and Other Visual Oddities. Robson. pp. 173–174. ISBN 978-1-86105-586-6. Archived from the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- ^ Stanek K, Ones D (20 November 2023). Of Anchors & Sails: Personality-Ability Trait Constellations. University of Minnesota. doi:10.24926/9781946135988. ISBN 978-1-946135-98-8.

- ^ "On the Perception of Incongruity: A Paradigm" by Jerome S. Bruner and Leo Postman. Journal of Personality, 18, pp. 206-223. 1949. Yorku.ca Archived 15 February 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Predictive Coding". Archived from the original on 5 December 2013. Retrieved 24 February 2011.

- ^ O'Regan JK (1992). "Solving the "real" mysteries of visual perception: The world as an outside memory". Canadian Journal of Psychology. 46 (3): 461–488. doi:10.1037/h0084327. ISSN 0008-4255. PMID 1486554.

- ^ O'Regan JK, Noë A (2001). "A sensorimotor account of vision and visual consciousness". Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 24 (5): 939–973. doi:10.1017/S0140525X01000115. ISSN 0140-525X. PMID 12239892.

- ^ Hatfield G (2023), "René Descartes", in Zalta EN, Nodelman U (eds.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2023 ed.), Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, retrieved 11 November 2023

- ^ Downing L (2021), "George Berkeley", in Zalta EN (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2021 ed.), Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, retrieved 11 November 2023

- ^ Rohlf M (2023), "Immanuel Kant", in Zalta EN, Nodelman U (eds.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2023 ed.), Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, retrieved 11 November 2023

Sources

[edit]Bibliography

[edit]- Arnheim, R. (1969). Visual Thinking. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24226-5.

- Flanagan, J. R., & Lederman, S. J. (2001). "'Neurobiology: Feeling bumps and holes. News and Views", Nature, 412(6845):389–91. (PDF)

- Gibson, J. J. (1966). The Senses Considered as Perceptual Systems, Houghton Mifflin.

- Gibson, J. J. (1987). The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. ISBN 0-89859-959-8

- Robles-De-La-Torre, G. (2006). "The Importance of the Sense of Touch in Virtual and Real Environments". IEEE MultiMedia,13(3), Special issue on Haptic User Interfaces for Multimedia Systems, pp. 24–30. (PDF)

External links

[edit]- Theories of Perception Several different aspects on perception

- Richard L Gregory Theories of Richard. L. Gregory.

- Comprehensive set of optical illusions, presented by Michael Bach.

- Optical Illusions Examples of well-known optical illusions.

- The Epistemology of Perception Article in the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Cognitive Penetrability of Perception and Epistemic Justification Article in the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy