Recent from talks

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Contribute something

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to A minor.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

A minor

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2025) |

| Relative key | C major |

|---|---|

| Parallel key | A major |

| Dominant key | E minor |

| Subdominant key | D minor |

| Component pitches | |

| A, B, C, D, E, F, G | |

A minor is a minor scale based on A, B, C, D, E, F, and G.[1] Its key signature has no flats or sharps.[1] Its relative major is C major and its parallel major is A major.

The A natural minor scale is:

Changes needed for the melodic and harmonic versions of the scale are written in with accidentals as necessary. The A harmonic minor and melodic minor scales are:

Scale degree chords

[edit]The scale degree chords of A minor are:

- Tonic – A minor

- Supertonic – B diminished

- Mediant – C major

- Subdominant – D minor

- Dominant – E minor

- Submediant – F major

- Subtonic – G major

Well-known compositions in A minor

[edit]- Johann Sebastian Bach

- English Suite No. 2, BWV 807

- Sonata No. 2 in A minor, BWV 1003

- Partita in A minor, BWV 1013

- Violin Concerto in A minor, BWV 1041

- Allein zu dir, Herr Jesu Christ, BWV 33

- Ludwig van Beethoven

- Violin Sonata No. 4, Op. 23

- String Quartet No. 15, Op. 132

- Bagatelle in A minor, "Für Elise"

- Johannes Brahms

- String Quartet No, 2, Op. 51/2

- Double Concerto, Op. 102

- Clarinet Trio, Op. 114

- Max Bruch

- Frédéric Chopin

- Antonín Dvořák

- String Quintet No. 1, Op. 1

- String Quartet No. 6, Op. 12

- String Quartet No. 7, Op. 16

- Violin Concerto, Op. 53

- Alexander Glazunov

- Violin concerto, Op. 82

- Edvard Grieg

- Piano Concerto, Op. 16

- Cello Sonata, Op. 36

- Johann Nepomuk Hummel

- Piano Concerto No. 2, Op. 85

- Franz Liszt

- Gustav Mahler

- Felix Mendelssohn

- Symphony No. 3, Scottish

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

- Piano Sonata No. 8, K. 310

- Rondo, K. 511

- Niccolò Paganini

- Sergei Rachmaninoff

- Isle of the Dead, Op. 29

- Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, Op. 43

- Symphony no. 3, Op. 44

- Maurice Ravel

- Camille Saint-Saëns

- Introduction and Rondo Capriccioso, Op. 28

- Cello Concerto No. 1, Op. 33

- Franz Schubert

- Clara Schumann

- Piano Concerto, Op. 7

- Robert Schumann

- Three Romances for Oboe and Piano, Op. 94

- Violin Sonata No. 1, Op. 105

- Piano Concerto, Op. 54

- Cello Concerto, Op. 129

- Jean Sibelius

- Symphony No. 4, Op. 63

- Dmitri Shostakovich

- Violin Concerto No. 1, Op. 99

- Georg Philipp Telemann

- Fantasia for Solo Flute No. 2

- Fantasia for Solo Violin No. 12

- Ralph Vaughan Williams

- Antonio Vivaldi

- Concerto for violin, Op. 3/6 RV 356

- Concerto for two violins, Op. 3/8 RV 522

- Concerto for violin, Op. 4/4 RV 357

- Concerto for violin, Op. 7/4 RV 354

- Concerto for violin, Op. 9/5 RV 358

References

[edit]- ^ a b "A Minor Scale". Berklee Pulse. Retrieved 19 May 2025.

External links

[edit] Media related to A minor at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to A minor at Wikimedia Commons

A minor

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia

A minor is a minor scale and key in Western music theory, consisting of the pitches A, B, C, D, E, F, and G in its natural form, with A as the tonic.[1] It serves as the relative minor of C major, sharing the same key signature of no sharps or flats, and is constructed by beginning the C major scale on its sixth degree.[2] The scale's minor third interval from the tonic (A to C) imparts a characteristic somber or melancholic quality compared to major scales.[3]

There are three primary variants of the A minor scale: the natural minor, which follows the descending pattern from C major; the harmonic minor, which raises the seventh degree to G♯ for a stronger resolution to the tonic; and the melodic minor, which raises both the sixth (to F♯) and seventh (to G♯) degrees when ascending, reverting to the natural form when descending.[1] These forms allow for varied harmonic and melodic possibilities, with the harmonic and melodic versions commonly used to create tension and leading tones in compositions.[4] In chord progressions, the diatonic chords of A minor include A minor (i), B diminished (ii°), C major (III), D minor (iv), E minor (v), F major (VI), and G major (VII).[5]

A minor has been employed extensively in classical and romantic music to evoke emotions such as tenderness, quiet melancholy, and pious devotion, as noted in historical key characteristic tables.[6] Notable works in A minor include Edvard Grieg's Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 16 (1868), known for its dramatic opening and Norwegian folk influences; Robert Schumann's Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 54 (1845), a lyrical staple of the Romantic repertoire; and Ludwig van Beethoven's Bagatelle in A minor, WoO 59 ("Für Elise," 1810), a beloved short piece featuring a simple yet haunting melody.[7][8][9] Other significant compositions encompass Felix Mendelssohn's Symphony No. 3 in A minor, Op. 56 ("Scottish," 1842) and Franz Schubert's Arpeggione Sonata in A minor, D. 821 (1824), highlighting the key's versatility in symphonic and chamber music.[10]

This pattern uses the open A string (5th string) for A and D (4th string open), with fretted notes at the 2nd fret on the 5th string (B), 3rd fret on the 5th string (C), 2nd fret on the 4th string (E), 2nd fret on the 3rd string (F), and 1st fret on the 2nd string (G); typical fingerings employ the index for 1st-fret notes, middle for 2nd-fret notes, and ring for 3rd-fret notes.[31]

These Roman numerals indicate the scale degree of the root, with lowercase for minor triads, uppercase for major, and ° for diminished.[44]

In terms of harmonic function, the i chord (A minor) serves as the tonic, providing resolution and stability; the iv chord (D minor) acts as the subdominant, introducing tension toward the dominant; and the v chord (E minor) functions as the dominant, though its minor quality creates a less conclusive pull compared to a major dominant in other contexts.[45] The remaining chords—ii° (supertonic), III (mediant), VI (submediant), and VII (subtonic)—support modal interchange and provide color, often substituting for primary functions in progressions.[46]

Extending these triads to seventh chords incorporates the next diatonic third above the fifth, yielding a set of four-note harmonies that add depth and tension.[42] For example, the i7 chord is A minor seventh (Am7: A–C–E–G), featuring a minor seventh interval; the ii°7 is B half-diminished seventh (Bø7: B–D–F–A); and the v7 is E minor seventh (Em7: E–G–B–D). The full set includes IIImaj7 (Cmaj7: C–E–G–B), iv7 (Dm7: D–F–A–C), VImaj7 (Fmaj7: F–A–C–E), and VII7 (G7: G–B–D–F).[43]

Chord inversions rearrange the notes to place a non-root in the bass, aiding voice leading by promoting stepwise motion and common tones between consecutive harmonies.[47] For the tonic i chord (Am), the first inversion (Am/C: C–E–A) doubles the third or fifth in upper voices while keeping the bass as C, allowing efficient connections such as from G major (VII) to Am/C via shared tones E and stepwise bass ascent from G to A (via passing note).[47] The second inversion (Am/E: E–A–C) is used sparingly for bass-line emphasis, with voice leading prioritizing contrary motion to the bass, such as descending upper voices from a preceding iv7 (Dm7: F–A–C–D in first inversion) to resolve the seventh downward.[42]

Fundamentals

Key Signature and Notation

A minor is a minor key that features no sharps or flats in its key signature, making it one of the simplest keys for notation in Western music. This key signature is identical to that of its relative major, C major. As the Aeolian mode of the C major scale, A minor provides a foundational tonality often used in compositions seeking a melancholic or introspective mood.[11][12][13] The natural A minor scale, which defines the key's basic pitches, ascends and descends using the sequence of notes A, B, C, D, E, F, G, returning to A. In staff notation, this scale is typically written in the treble clef starting on the second space (A4), progressing through the spaces and lines for B, C, D, E, F, and G—all without any accidental symbols due to the absence of sharps or flats. For visual representation on a keyboard instrument like the piano, these notes correspond exclusively to the white keys, beginning from the A located just below middle C (A3).[12][14] In practical application, A minor accommodates standard instrument tunings effectively. On the guitar in standard tuning (low to high: E₂, A₂, D₃, G₃, B₃, E₄), the open strings facilitate easy access to A minor tonality, as the basic A minor triad in open position uses the open A and high E strings, with the B string fretted at the first fret and the D and G strings at the second fret, while the low E string is typically muted. Similarly, on the piano, the key's position centers around the central white keys, allowing performers to navigate the scale fluidly without black key involvement.[15][16][17]Relative and Parallel Relationships

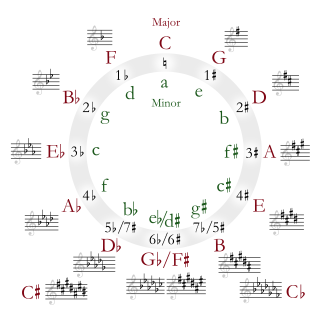

In music theory, the relative major of A minor is C major, as A minor is constructed on the sixth degree of the C major scale, resulting in both keys sharing the same key signature of no sharps or flats and the identical set of notes: A, B, C, D, E, F, G.[18][19] This relationship allows composers to shift between the two keys seamlessly, often using shared diatonic chords for modulation, as the tonal center moves from A to C without altering the pitch content.[20] The parallel major of A minor is A major, which uses the same tonic note A but features a key signature with three sharps: F♯, C♯, and G♯, creating a scale of A, B, C♯, D, E, F♯, G♯.[21][22] This parallel relationship enables mode shifts that maintain the root while altering the overall character; A major typically evokes brighter, more triumphant expressions in compositions, whereas A minor lends itself to introspective or somber passages, allowing writers to heighten emotional contrast within the same tonic framework.[23] Within the circle of fifths, A minor appears as the relative minor to C major, positioned adjacent to keys like G major, F major, E minor, and D minor, which share common tones and facilitate smooth modulations through pivot chords or dominant resolutions.[24] This placement underscores A minor's role in tonal progressions, where moving clockwise or counterclockwise by fifths supports key changes that enhance harmonic variety in larger works.[25] For practical application, consider a simple melody such as the ascending pattern A-B-C-D in A minor; transposing it to its relative major C major involves reinterpreting the same pitches with C as the tonic, yielding C-D-E-F, which shifts the perceived resolution and mode without pitch alteration.[18] Similarly, modulating to the parallel A major might involve introducing the raised third (C♯) via a pivot chord like A major itself, transforming a phrase like A-E-F-E in A minor to A-E-F♯-E in A major for a brighter tonal shift.[20]Scale Construction

Natural Minor Scale

The natural A minor scale, also known as the A Aeolian mode, is a diatonic scale consisting of the pitches A, B, C, D, E, F, G, returning to A.[26] This sequence corresponds to the scale degrees 1 (A), 2 (B), ♭3 (C), 4 (D), 5 (E), ♭6 (F), and ♭7 (G).[27] The interval structure follows the pattern of whole step, half step, whole step, whole step, half step, whole step, whole step (W-H-W-W-H-W-W).[28] As the sixth mode of the C major scale, A Aeolian uses the same set of pitches as C major (C, D, E, F, G, A, B) but begins and ends on A, creating its characteristic minor tonality.[13] Like its parallel major counterpart A major, the natural A minor scale features no sharps or flats in its key signature.[29] On piano, the standard one-octave fingering for the right hand ascending is thumb (1) on A, index (2) on B, middle (3) on C, thumb (1) on D, index (2) on E, middle (3) on F, ring (4) on G, and pinky (5) on the upper A; for the left hand ascending, it is pinky (5) on A, ring (4) on B, middle (3) on C, index (2) on D, thumb (1) on E, middle (3) on F, index (2) on G, and thumb (1) on the upper A.[30] For guitar, a common open-position tablature for the natural A minor scale spans the low E string to the high E string as follows:e|--0--|

B|--1--|

G|--2--|

D|--2--|

A|--0--|

E|--0--3-2-0--

e|--0--|

B|--1--|

G|--2--|

D|--2--|

A|--0--|

E|--0--3-2-0--

Harmonic Minor Scale

The harmonic minor scale in A minor is formed by raising the seventh degree of the natural minor scale from G to G♯, resulting in the pitches A, B, C, D, E, F, G♯, and A. This single alteration enables the construction of a major dominant chord, E major (E-G♯-B), which strengthens the pull toward the tonic in harmonic progressions.[32] The interval structure follows a pattern of whole step (W), half step (H), whole step, whole step, half step, augmented second (W+H), and half step, producing the distinctive augmented second between the lowered sixth (F) and raised seventh (G♯). This pattern arises specifically from the raised seventh, distinguishing it from the natural minor's even whole and half steps.[33] The raised seventh serves as a leading tone, resolving upward to the tonic A and facilitating the dominant-to-tonic cadence essential in classical harmony, where it supports the V chord's major quality for greater tension and resolution.[34] In notation, the ascending form is A-B-C-D-E-F-G♯-A, while descending lines typically revert to the natural minor scale (A-G-F-E-D-C-B-A) to eliminate the awkward augmented second in downward motion.[35]Melodic Minor Scale

The melodic minor scale in A minor is an adaptive variant of the natural minor scale, featuring alterations to the sixth and seventh degrees for ascending melodies while reverting to the natural form when descending. Ascending, the scale raises the sixth degree from F to F♯ and the seventh from G to G♯, resulting in the pitches A, B, C, D, E, F♯, G♯, A.[36] Descending, it follows the natural minor pattern: A, G, F, E, D, C, B, A.[36] This bidirectional adjustment addresses melodic challenges in the harmonic minor scale, which shares the raised seventh but retains the lowered sixth, creating an augmented second interval that can disrupt smooth lines.[37] The ascending interval pattern of the A melodic minor scale is whole step–half step–whole step–whole step–whole step–whole step–half step (W-H-W-W-W-W-H), mirroring the major scale's structure except for the lowered third degree.[38] This configuration promotes smoother stepwise motion in ascending phrases by eliminating the awkward leap between the lowered sixth and raised seventh found in the harmonic minor, allowing for more fluid and diatonic-like melodic contours akin to those in major keys.[39] The melodic minor scale evolved during the early Baroque period, spanning the 17th and 18th centuries, as composers sought to refine minor key melodies for greater expressiveness and ease of performance.[39] By the 18th century, it was in regular use alongside the natural and harmonic forms, reflecting practical adaptations in European musical practice to enhance melodic fluidity without altering core harmonic functions.[40] In classical music, the A melodic minor appears in ascending violin and keyboard lines, such as those in Bach's Partita No. 2 in D minor (transposed contexts) or Mozart's violin sonatas in minor keys, where it facilitates lyrical ascents.[37] In jazz, it underpins improvisational lines over minor ii-V-i progressions, as in modal applications during solos on standards like "Autumn Leaves" (adaptable to A minor contexts), maintaining the raised sixth and seventh in both directions for consistent tension resolution.[41]Harmony and Chords

Diatonic Chords

In the natural minor scale of A, the diatonic chords are constructed by stacking thirds on each scale degree, resulting in seven primary triads that form the harmonic foundation of the key. These triads follow the pattern of minor, diminished, major, minor, minor, major, and major qualities, respectively.[42][43] The following table outlines the diatonic triads in A minor, including their Roman numeral notation, root position formulas, and common names:| Roman Numeral | Chord Name | Notes (Root Position) |

|---|---|---|

| i | A minor | A–C–E |

| ii° | B diminished | B–D–F |

| III | C major | C–E–G |

| iv | D minor | D–F–A |

| v | E minor | E–G–B |

| VI | F major | F–A–C |

| VII | G major | G–B–D |