Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

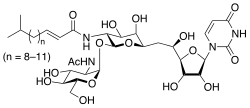

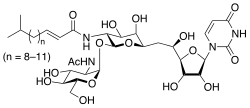

Tunicamycin

View on Wikipedia

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

(E)-N-[(2S,3R,4R,5R,6R)-2-[(2R,3R,4R,5S,6R)-

3-acetamido-4,5-dihydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)oxan-2-yl]oxy- 6-[2-[(2R,3S,4R,5R)-5-(2,4-dioxopyrimidin-1-yl)- 3,4-dihydroxyoxolan-2-yl]-2-hydroxyethyl]-4,5-dihydroxyoxan- 3-yl]-5-methylhex-2-enamide | |

| Other names

NSC 177382

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.115.295 |

| EC Number |

|

| MeSH | Tunicamycin |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C39H64N4O16 | |

| Molar mass | N/A |

| Hazards | |

| GHS labelling:[1] | |

| |

| Danger | |

| H300 | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

This article may be too technical for most readers to understand. (October 2020) |

Tunicamycin is a mixture of homologous nucleoside antibiotics that inhibits the UDP-HexNAc: polyprenol-P HexNAc-1-P family of enzymes. In eukaryotes, this includes the enzyme GlcNAc phosphotransferase (GPT), which catalyzes the transfer of N-acetylglucosamine-1-phosphate from UDP-N-acetylglucosamine to dolichol phosphate in the first step of glycoprotein synthesis. Tunicamycin blocks N-linked glycosylation (N-glycans) and treatment of cultured human cells with tunicamycin causes cell cycle arrest in G1 phase. It is used as an experimental tool in biology, e.g. to induce unfolded protein response.[2] Tunicamycin is produced by several bacteria, including Streptomyces clavuligerus and Streptomyces lysosuperificus.

Tunicamycin homologues have varying molecular weights owing to the variability in fatty acid side chain conjugates.[3]

Biosynthesis

[edit]The biosynthesis of tunicamycins was studied in Streptomyces chartreusis and a proposed biosynthetic pathway was characterized. The bacteria utilize the enzymes in the tun gene cluster (TunA-N) to make tunicamycins.[4]

TunA uses the starter unit uridine diphosphate-N-acetyl-glucosamine (UDP-GlcNAc) and catalyzes the dehydration of the 6’ hydroxyl group. First, a Tyr residue in TunA abstracts a proton from the 4’ hydroxyl group, forming a ketone at that position. A hydride is subsequently abstracted from the 4’ carbon by NAD+, forming NADH. The ketone is stabilized by hydrogen bonding from the Tyr residue, and a nearby Thr residue. A glutamate residue then abstracts a proton from the 5’ carbon, pushing the electrons up to form a double bond between the 5’ and 6’ carbon. A nearby cysteine donates a proton to the hydroxyl group as it leaves as water. NADH donates a hydride to the 4’ carbon, reforming a hydroxide in that position and forming UDP-6’-deoxy-5-6-ene-GlcNAc. TunF then catalyzes the epimerization of the intermediate to UDP-6’-deoxy-5-6-ene-GalNAc, changing the 4’ hydroxyl from the equatorial to axial position.[5]

The other starter unit for tunicamycin is uridine, which is produced from uridine triphosphate (UTP). TunN is a nucleotide diphosphatase, and catalyzes the removal of pyrophosphate from UTP to form uridine monophosphate. The last phosphate is removed by the putative monophosphatase, TunG.

Once uridine and UDP-6’-deoxy-5-6-ene-GalNAc are produced, TunB catalyzes their linkage at the 6’ carbon of UDP-6’-deoxy-5-6-ene-GalNAc. TunB uses S-adenyslmethionine (SAM) to form a radical on the 5’ carbon of the ribose on uracil. TunM is thought to catalyze the formation of a new bond between the 5’ carbon of uridine and the 6’ carbon of UDP-6’-deoxy-5-6-ene-GalNAc using the electron from the uridine radical and one of the electrons from the double bond of UDP-6’-deoxy-5-6-ene-GalNAc. The radical on UDP-6’-deoxy-5-6-ene-GalNAc is then quenched by abstracting a hydrogen from SAM.[6] The resulting molecule is UDP-N-acetyl-tunicamine. TunH then catalyzes the hydrolysis of UDP from UDP-N-acetyl-tunicamine. Another molecule of UDP-GlcNAc is introduced, and a β-1,1 glycosidic bond is subsequently formed, catalyzed by TunD. The resulting molecule is deacetylated by TunE. TunL and a fatty acyl-ACP ligase are used to load metabolic fatty acids onto the acyl carrier protein, TunK. TunC then attaches the fatty acid to the free amine, producing tunicamycin.

See also

[edit]- Glycosylation - tunicamycin blocks all N-glycosylation of proteins

- Glycoprotein

- Streptomyces

References

[edit]- ^ "C&L Inventory". echa.europa.eu.

- ^ Chan SW, Egan PA (2005). "Hepatitis C virus envelope proteins regulate CHOP via induction of the unfolded protein response". The FASEB Journal. 19 (11): 1510–1512. doi:10.1096/fj.04-3455fje. PMID 16006626.

- ^ [1] Tunicamycin product details]

- ^ Wyszynski F, Hesketh A, Bibb M, Davis B (2010). "Dissecting tunicamycin biosynthesis by genome mining: cloning and heterologous expression of a minimal gene cluster". Chemical Science. 1 (5): 581. doi:10.1039/c0sc00325e.

- ^ Wyszynski F, Lee S, Yabe T, Wang H, Gomez-Escribano JP, Bibb M (July 2012). "Biosynthesis of the tunicamycin antibiotics proceeds via unique exo-glycal intermediates". Nature Chemistry. 4 (7): 539–546. Bibcode:2012NatCh...4..539W. doi:10.1038/nchem.1351. PMID 22717438.

- ^ Giese B (August 1989). "The Stereoselectivity of Intermolecular Free Radical Reactions [New Synthetic Methods (78)]". Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English. 28 (8): 969–980. doi:10.1002/anie.198909693.

External links

[edit]- Book section of Essentials in Glycobiology (1999) Tunicamycin: Inhibition of DOL-PP-GlcNAc Assembly