Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Tuscan wine

View on Wikipedia

Tuscan wine is Italian wine from the Tuscany region. Located in central Italy along the Tyrrhenian coast, Tuscany is home to some of the world's most notable wine regions. Chianti, Brunello di Montalcino and Vino Nobile di Montepulciano are primarily made with Sangiovese grape whereas the Vernaccia grape is the basis of the white Vernaccia di San Gimignano. Tuscany is also known for the dessert wine Vin Santo, made from a variety of the region's grapes. Tuscany has forty-one Denominazioni di origine controllata (DOC) and eleven Denominazioni di Origine Controllata e Garantita (DOCG). In the 1970s a new class of wines known in the trade as "Super Tuscans" emerged. These wines were made outside DOC/DOCG regulations but were considered of high quality and commanded high prices. Many of these wines became cult wines. In the reformation of the Italian classification system many of the original Super Tuscans now qualify as DOC or DOCG wines (such as the new Bolgheri label) but some producers still prefer the declassified rankings or to use the Indicazione Geografica Tipica (IGT) classification of Toscana. Tuscany has six sub-categories of IGT wines today.

History

[edit]

The history of viticulture in Tuscany dates back to its settlements by the Etruscans in the 8th century BC. Amphora remnants originating in the region show that Tuscan wine was exported to southern Italy and Gaul as early as the 7th century BC. By the 3rd century BC, there were literary references by Greek writers about the quality of Tuscan wine.[1]: 259 From the fall of the Roman Empire and throughout the Middle Ages, monasteries were the main purveyors of wines in the region. As the aristocratic and merchant classes emerged, they inherited the sharecropping system of agriculture known as mezzadria. This system took its name from the arrangement whereby the landowner provides the land and resources for planting in exchange for half ("mezza") of the yearly crop. Many Tuscan landowners would turn their half of the grape harvest into wine that would be sold to merchants in Florence. The earliest reference of Florentine wine retailers dates to 1079 and a guild was created in 1282.[1]: 715–716

The Arte dei Vinattieri guild established strict regulations on how the Florentine wine merchants could conduct business. No wine was to be sold within 100 yards (91 m) of a church. Wine merchants were also prohibited from serving children under age 15 or to prostitutes, ruffians and thieves. In the 14th century, an average of 7.9 million US gallons (30,000 m3) of wine was sold every year in Florence. The earliest references to Vino Nobile di Montepulciano wine date to the late 14th century. The first recorded mention of wine from Chianti was by the Tuscan merchant Francesco di Marco Datini, the "merchant of Prato", who described it as a light, white wine. The Vernaccia and Greco wines of San Gimignano were considered luxury items and treasured as gifts over saffron. During this period Tuscan winemakers began experimenting with new techniques and invented the process of governo which helped to stabilize the wines and ferment the sugar content sufficiently to make them dry. In 1685 the Tuscan author Francesco Redi wrote Bacco in Toscana, a 980-line poem describing the wines of Tuscany.[1]: 715–716

Following the end of the Napoleonic Wars, Tuscany returned to the rule of the Habsburgs. It was at this point that the statesman Bettino Ricasoli inherited his family ancestral estate in Broglio located in the heart of the Chianti Classico zone. Determined to improve the estate, Ricasoli traveled throughout Germany and France, studying the grape varieties and viticultural practices. He imported several of the varieties back to Tuscany and experimented with different varieties in his vineyards. However, in his experiments Ricasoli discovered that three local varieties—Sangiovese, Canaiolo and Malvasia—produced the best wine. In 1848, revolutions broke out in Italy and Ricasoli's beloved wife died, leaving him with little interest to devote to wine. In the 1850s Oidium Uncinula necator and war devastated most of Tuscany's vineyards with many peasant farmers leaving for other parts of Italy or to emigrate to the Americas.[2]

Climate and geography

[edit]

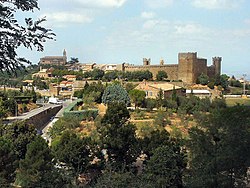

Tuscany (which includes seven coastal islands) is Italy's fifth largest region. It is bordered to the northwest by Liguria, the north by Emilia-Romagna, Umbria to the east and Lazio to the south. To the west is the Tyrrhenian Sea which gives the area a warm Mediterranean climate. The terrain is quite hilly (over 68% of the terrain), progressing inward to the Apennine Mountains along the border with Emilia-Romagna. The hills have a tempering effect on the summertime heat, with many vineyards planted on the higher elevations of the hillsides.[3]

The Sangiovese grape performs better when it can receive more direct sunlight, which is a benefit of the many hillside vineyards in Tuscany. The majority of the region's vineyards are found at altitudes of 500–1,600 ft (150–490 m). The higher elevations also increase the diurnal temperature variation, helping the grapes maintain their balance of sugars and acidity as well as their aromatic qualities.[1]: 703

Wines and grapes

[edit]

After Piedmont and the Veneto, Tuscany produces the third highest volume of DOC/G quality wines. Tuscany is Italy's third most planted region (behind Sicily and Apulia) but it is eighth in production volume. This is partly because the soil of Tuscany is very poor, and producers emphasize low yields and higher quality levels in their wine. More than 80% of the region's production is red wine.[3]

The Sangiovese grape is Tuscany's most prominent grape; however, many different clonal varieties exist, as many towns have their own local version of Sangiovese. Cabernet Sauvignon has been planted in Tuscany for over 250 years, but has only recently become associated with the region due to the rise of the Super Tuscans. Other international varieties found in Tuscany include Cabernet franc, Chardonnay, Merlot, Pinot noir, Sauvignon blanc and Syrah. Of the many local red grape varieties Canaiolo, Colorino, Malvasia nera and Mammolo are the most widely planted. For Tuscan white wines, Trebbiano is the most widely planted variety followed by Malvasia, Vermentino and Vernaccia.[3]

Super Tuscans

[edit]

Super Tuscans are an unofficial category of Tuscan wines, not recognized within the Italian wine classification system. Although an extraordinary number of wines claim to be "the first Super Tuscan," most would agree that this credit belongs to Sassicaia, the brainchild of marchese Mario Incisa della Rocchetta, who planted Cabernet Sauvignon at his Tenuta San Guido estate in Bolgheri back in 1944. It was for many years the marchese's personal wine, until, starting with the 1968 vintage, it was released commercially in 1971.[4] The growth of Super Tuscans is also rooted in the restrictive DOC practices of the Chianti zone prior to the 1990s. During this time Chianti could be composed of no more than 70% Sangiovese and had to include at least 10% of one of the local white wine grapes. Producers who deviated from these regulations could not use the Chianti name on their wine labels and would be classified as vino da tavola—Italy's lowest wine designation. By the 1970s, the consumer market for Chianti wines was suffering and the wines were widely perceived to be lacking quality. Many Tuscan wine producers thought they could produce a better quality wine if they were not hindered by the DOC regulations.[5]

The marchese Piero Antinori was one of the first to create a "Chianti-style" wine that ignored the DOC regulations, releasing a 1971 Sangiovese–Cabernet Sauvignon blend known as Tignanello in 1978. He was inspired by Sassicaia, of which he was given the sale agency by his uncle Mario Incisa della Rocchetta.[4] Other producers followed suit and soon the prices for these Super Tuscans were consistently beating the prices of some of most well known Chianti. Rather than rely on name recognition of the Chianti region, the Super Tuscan producers sought to create a wine brand that would be recognizable on its own merits by consumers. By the late 1980s, the trend of creating high-quality non-DOC wines had spread to other regions of Tuscany, as well as Piedmont and Veneto. Modification to the Chianti DOC regulation attempted to "correct" the issues of Super Tuscans, so that many of the original Super Tuscans would now qualify as standard DOC/G Chianti. Most producers have brought their Super Tuscans back under legal regulations, notably since the creation of the less restrictive IGT Toscana designation in 1992 and the DOC Bolgheri designation in 1994, while the pioneer Sassicaia was prized with its own exclusive Bolgheri Sassicaia DOC.[5]

In addition to wines based on the Sangiovese grape, many well known Super Tuscans are based on a "Bordeaux-blend", meaning a combination of grapes typical for Bordeaux (especially Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot). These grapes are not originally from the region, but imported and planted later. The climate in Tuscany has proven to be very good for these grapes.

Vin Santo

[edit]While Tuscany is not the only Italian region to make the passito dessert wine Vin Santo (meaning "holy wine"), the Tuscan versions of the wine are well regarded and sought for by wine consumers. The best-known version is from the Chianti Classico and is produced with a blend of Trebbiano and Malvasia Bianca. Red and rosé styles are also produced mostly based on the Sangiovese grape. The wines are aged in barrels for a minimum of three years, four if it is meant to be a Riserva.[6]

Wine regions

[edit]Tuscany's 41 DOC and 11 DOCG are spread out across the region's ten provinces.[7]

Brunello di Montalcino

[edit]

Brunello is the name of the local Sangiovese variety that is grown around the village of Montalcino. Located south of the Chianti Classico zone, the Montalcino range is drier and warmer than Chianti. Monte Amiata shields the area from the winds coming from the southeast. Many of the area's vineyards are located on the hillsides leading up towards the mountain to elevations of around 1,640 ft (500 m) though some vineyards can be found in lower-lying areas. The wines of northern and eastern regions tend to ripen more slowly and produce more perfumed and lighter wines. The southern and western regions are warmer, and the resulting wines tend to be richer and more intense.[6]

The Brunello variety of Sangiovese seems to flourish in this terroir, ripening easily and consistently producing wines of deep color, extract, richness with full bodies and good balance of tannins. In the mid-19th century, a local farmer named Clemente Santi is believed to have isolated the Brunello clone and planted it in this region. His grandson Ferruccio Biondi-Santi helped to popularize Brunello di Montalcino in the later half of the 19th century. In the 1980s, it was the first wine to earn the DOCG classification. Today there are about two hundred growers in the Montalcino region producing about 333,000 cases of Brunello di Montalcino a year.[6]

Brunello di Montalcino wines are required to be aged for at least four years prior to being released, with riserva wines needing five years. Brunellos tend to be very tight and tannic in their youth, needing at least a decade or two before they start to soften with wines from excellent vintages having the potential to do well past 50 years. In 1984, the Montalcino region was granted the DOC designation Rosso di Montalcino. Often called Baby Brunellos, these wines are typically made from the same grapes, vineyards and style as the regular Brunello di Montalcino but are not aged as long. While similar to Brunellos in flavor and aromas, these wines are often lighter in body and more approachable in their youth.[6]

Carmignano

[edit]

The Carmignano region was one of the first Tuscan regions to be permitted to use Cabernet Sauvignon and Cabernet Franc in their DOC wines since those varieties had a long history of being grown in the region.[8]

Noted for the quality of its wines since the Middle Ages, Carmignano was identified by Cosimo III de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany as one of the superior wine producing areas of Tuscany and granted special legal protections in 1716. In the 18th century, the producers of the Carmignano region developed a tradition of blending Sangiovese with Cabernet Sauvignon, long before the practice became popularized by the "Super Tuscan" of the late 20th century.[9] In 1975, the region was awarded Denominazione di origine controllata (DOC) status and subsequently promoted to Denominazione di Origine Controllata e Garantita (DOCG) status in 1990 (retroactive to the 1988 vintage). Today Carmignano has approximately 270 acres (110 ha) planted, producing nearly 71,500 US gallons (271,000 L) of DOCG designated wine a year.[1]: 140

Chianti

[edit]

Located in the central region of Tuscany, the Chianti zone is Tuscany's largest classified wine region and produces over eight million cases a year. In addition to producing the well known red Chianti wine, the Chianti zone also produces white, other Rosso reds and Vin Santo. The region is split into two DOCG- Chianti and Chianti Classico. The Chianti Classico zone covers the area between Florence and Siena, which is the original Chianti region, and where some of the best expressions of Chianti wine are produced. The larger Chianti DOCG zone is further divided in six DOC sub-zones and areas in the western part of the province of Pisa, the Florentine hills north of Chianti Classico in the province of Florence, the Siena hills south of the city in the province of Siena, the province of Arezzo and the area around the communes of Rufina and Pistoia.[10]

Since 1996, Chianti is permitted to include as little as 75% Sangiovese, a maximum of 10% Canaiolo, up to 10% of the white wine grapes Malvasia and Trebbiano and up to 15% of any other red wine grape grown in the region, such as Cabernet Sauvignon. This variety of grapes and usage is one reason why Chianti can vary widely from producer to producer. The use of white grapes in the blend could alter the style of Chianti by softening the wines with a higher percentage of white grapes, typically indicating that the wine is meant to be drunk younger and not aged for long. In general, Chianti Classicos are described as medium-bodied wines with firm, dry tannins. The characteristic aroma is cherry but it can also carry nutty and floral notes as well.[10]

In 2006, the use of white grapes Trebbiano and Malvasia was prohibited (except in Chianti Colli Senesi until the 2015 vintage). Local laws also require wines to have a minimum of 70% Sangiovese (and 80% for the more prestigious Chianti Classico DOCG). The native varieties Canaiolo and Colorino are also permitted, as are the international classics, Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot, to a limited degree.[11]

The Chianti Classico region covers approximately 100 sq mi (260 km2) and includes the communes of Castellina, Gaiole, Greve and Radda and Panzano, as well as parts of four other neighboring communes. The terroir of the Classico zone varies throughout the region depending on the vineyards' altitude, soil type and distance from the Arno River. The soils of the northern communes, such as Greve, are richer in clay deposits while those in the southern communes, like Gaiole, are harder and stonier. Riserva Chianti is aged for at least 27 months, some of it in oak, and must have a minimum alcohol content of 12.5%. Wines from the Chianti DOCG can carry the name of one of the six sub-zones or just the Chianti designation. The Chianti Superiore designation refers to wines produced in the provinces of Florence and Siena but not in the Classico zone.[10]

Bolgheri

[edit]

The DOC Bolgheri region of the Livorno province is home to one of the original Super Tuscan wines Sassicaia, first made in 1944 produced by the marchesi Incisa della Rochetta, cousin of the Antinori family. The DOC Bolgheri region is also home to the Super Tuscan wine Ornellaia which was featured in the film Mondovino as well as Tignanello from Marchesi Antinori.

Vernaccia di San Gimignano

[edit]

Vernaccia di San Gimignano is a white wine made from the Vernaccia grape in the areas around San Gimignano. In 1966, it was the first wine to receive a DOC designation. This wine style has been made in the area for over seven centuries. The wine is dry and full-bodied with earthy notes of honey and minerals. In some styles it can be made to emphasize the fruit more and some producers have experimented with aging or fermenting the wine in oak barrels in order to give the wine a sense of creaminess or toastiness.[6]

Vino Nobile di Montepulciano

[edit]

The Vino Nobile di Montepulciano received its DOCG status shortly after Brunello di Montalcino, in 1980. The DOCG covers the red wine of the Montepulciano area. The wine received its name in the 17th century, when it was the favorite wine of the Tuscan nobility. Located in the southeastern region of Tuscany, the climate of the region is strongly influenced by the sea. The variety of Sangiovese in Montepulciano is known as Prugnolo Gentile and is required to account for at least 80% of the wine. Traditionally Canaiolo and Mammolo make up the remaining part of the blend but some producers have begun to experiment with Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot.[8]

The wines are required to age two years prior to release, with an additional year if it is to be a riserva. The recent use of French oak barrels has increased the body and intensity of the wines which are noted for their plummy fruit, almond notes and smooth tannins.[8]

The origin of Valdichiana wines

[edit]In Etruscan times, Valdichiana, an area which presently stretches along the Southeastern part of Tuscany up to the Florence-Rome road ramification, was called the "Breadbasket of Etruria". However, its hills were already dotted with vineyards. Later on, Plinius the Elder would describe the quality of these wines as follows: Talpone (red) and Ethesiaca (white). This was a vine growing culture spreading over the hills of the Tuscan part of Valdichiana surrounding the important commercial centres of Foiano della Chiana, Lucignano, Cortona, Montepulciano and Arezzo. The importance given to this economical activity was confirmed in the following years in successive stages in the writings of the Bishopric of Arezzo in Valdichiana Champagne. During the 1800s, the merchants of Bourgogne and Champagne decided to use the wines of Tuscan Valdichiana due to their renowned quality as a base for their champagnes after the phylloxera or vine-pest had destroyed their vineyards.

The wine making tradition was enriched and endorsed in the late 1960s and early 1970s with the DOC guarantee of origin recognition thanks to the effort of few noble families such as Della Stufa (Castello del Calcione, Lucignano) and Mancini Griffoli (Fattoria Santa Vittoria,[12] Pozzo della Chiana).

The first policy document of 1972 only protected the denomination of the "Virgin White Valdichiana" type. Later, the policy document was modified and enriched to include the entire selection of wines produced in the Tuscan Valdichiana. In 1989, the DOC guarantee of origin was extended to the sparkling and spumante types. In 1993, output was lowered and modified. Later, in 1999, a production policy was put in action for white berry types (chardonnay and grechetto), red berry types (red, rosato, sangiovese), and Vin Santo, thus fulfilling the aspirations of the producers after more than thirty years. In 1999, the DOC guarantee of origin also varied the name "Valdichiana", and in 2011 with DM 22/11/11, the "Tuscan Valdichiana" denomination was further varied with the aim of giving the exact perception that the wine produced there comes from the part of the Valdichiana that is situated in the Tuscan region in the provinces of Arezzo and Siena. This allowed the plan of promotion to strengthen the fundamental, unique, strong, and essential bond with its territory.

Other Tuscan wines

[edit]The Pomino region near Rufina has been historically known for the prevalence of the French wine grape varieties, making wines from both Cabernets as well as Chardonnay, Merlot, Pinot blanc, Pinot grigio in addition to the local Italian varieties. The Frescobaldi family is one of the area's most prominent wine producers.

In southern Tuscany, towards the region of Latium, is the area of Maremma which has its own IGT designation Maremma Toscana. Maremma is also home to Tuscany's newest DOCG, Morellino di Scansano, which makes a fragrant, dry Sangiovese based wine. The province of Grosseto is one of Tuscany's emerging wine regions with eight DOC designations, half of which were created in the late 1990s. It includes the Monteregio di Massa Marittima region which has been recently the recipient of foreign investment in the area's wine, especially by "flying winemakers". The Parrina region is known for its white wine blend of Trebbiano and Ansonica. The wine Bianco di Pitigliano is known for its eclectic mix of white wine grapes in the blend including Chardonnay, the Greco sub variety of Trebbiano, Grechetto, Malvasia, Pinot blanc, Verdello and Welschriesling.[8] In Maremma, a hidden gem with many wineries, is Poggio Argentiera winery which makes Morellino di Scansano and other wines.

The wines of Montecarlo region include several varieties that are not commonly found in Tuscan wines including Sémillon and Roussanne. The minor Chianti grape Ciliegiolo is also popular here. The island of Elba has one of the longest winemaking histories in Tuscany and is home to its own DOC. Some of the wines produced here include a sparkling Trebbiano wine, a sweet Ansonica passito, and a semi-sweet dessert wine from Aleatico.[8]

List of approved quality labels for Tuscan wines

[edit]DOCG

[edit]- Brunello di Montalcino (Rosso as normale and Riserva), produced in the province of Siena

- Carmignano (Rosso as normale and Riserva), produced in the provinces of Firenze and Prato

- Chianti (Rosso as normale and Riserva), produced in the provinces of Arezzo, Firenze, Pisa, Pistoia, Prato and Siena; with the option to indicate one of the sub-regions:

- Classico as normale and Riserva, produced in the provinces of Firenze and Siena[a]

- Colli Aretini as normale and Riserva produced in the province of Arezzo

- Colli Senesi as normale and Riserva, produced in the province of Siena

- Colli Fiorentini as normale and Riserva, produced in the province of Firenze

- Colline Pisane as normale and Riserva, produced in the province of Pisa

- Montalbano as normale and Riserva, produced in the provinces of Firenze, Pistoia and Prato

- Montespertoli as normale and Riserva, produced in the province of Pisa

- Rufina as normale and Riserva, produced in the province of Firenze

- Chianti Superiore, produced throughout the Chianti region with the exception of the classico sub-region.

- Elba Aleatico passito produced on the island of Elba in the province of Livorno

- Montecucco Sangiovese produced in the province of Grosseto

- Morellino di Scansano (Rosso as normale and Riserva), produced in the province of Grosseto

- Suvereto produced in the province of Livorno

- Val di Cornia Rosso produced in the province of Livorno and Pisa

- Vernaccia di San Gimignano (Bianco as normale and Riserva), produced in the province of Siena

- Vino Nobile di Montepulciano (Rosso as normal and Riserva), produced in the province of Siena

DOC

[edit]- Ansonica Costa dell'Argentario produced in the province of Grosseto

- Barco Reale di Carmignano produced in the provinces of Firenze and Prato

- Bianco della Valdinievole produced in the province of Pistoia

- Bianco dell'Empolese produced in the provinces of Firenze and Pistoia

- Bianco di Pitigliano produced in the province of Grosseto

- Bianco Pisano di San Torpè produced in the province of Pisa

- Bianco Vergine della Valdichiana produced in the provinces of Arezzo and Siena

- Bolgheri produced in the province of Livorno

- Bolgheri Sassicaia produced in the province of Livorno

- Candia dei Colli Apuani produced in the province of Massa-Carrara

- Capalbio produced in the province of Grosseto

- Colli dell'Etruria Centrale produced in the provinces of Arezzo, Firenze, Pisa, Pistoia, Prato and Siena

- Colli di Luni an inter-regional DOC produced in the provinces of Massa-Carrara (Toscana) and of La Spezia (Liguria)

- Colline Lucchesi produced in the province of Lucca

- Cortona produced in the province of Arezzo

- Elba produced in the province of Livorno

- Grance Senesi produced in the province of Siena

- Grechetto Valdichiana Toscana Doc produced in the provinces of Arezzo

- Maremma Toscana produced in the province of Grosseto

- Montecarlo produced in the province of Lucca

- Montecucco produced in the province of Grosseto

- Monteregio di Massa Marittima produced in the province of Grosseto

- Montescudaio produced in the province of Pisa

- Moscadello di Montalcino produced in the province of Siena

- Orcia produced in the province of Siena

- Parrina produced in the province of Grosseto

- Pomino produced in the province of Firenze

- Rosso di Montalcino produced in the province of Siena

- Rosso di Montepulciano produced in the province of Siena

- San Gimignano produced in the province of Siena

- San Torpè produced in the province of Pisa

- Sant'Antimo produced in the province of Siena

- Sovana produced in the province of Grosseto

- Terratico di Bibbona

- Terre di Casole

- Terre di Pisa in the province of Pisa

- Val d'Arbia produced in the province of Siena

- Val d'Arno di Sopra

- Val di Cornia

- Valdichiana Toscana

- Valdinievole produced in the Province of Pistoia

- Vinsanto Valdichiana Toscana Doc produced in the provinces of Arezzo

- Vin Santo del Chianti produced in the provinces of Arezzo, Firenze, Pisa, Pistoia, Prato and Siena

- Vin Santo del Chianti Classico produced in the provinces of Firenze and Siena

- Vin Santo del Carmignano

- Vin Santo di Montepulciano produced in the province of Siena

IGT

[edit]- Alta Valle della Greve (Bianco; Rosato; Rosso in the styles normale and Novello) produced in the province of Firenze.

- Colli della Toscana Centrale (Bianco in the styles normale and Frizzante; Rosato; Rosso in the styles normale and Novello) produced in the provinces of Arezzo, Firenze, Pistoia, Prato and Siena.

- Costa Toscana (Bianco in the styles normale and Frizzante; Rosato; Rosso in the styles normale and Novello) produced in the province of Grosseto.

- Toscano or Toscana (Bianco in the styles normale, Frizzante and Abboccato; Rosato in the styles normale and Abboccato; Rosso in the styles normale, Abboccato and Novello) produced throughout the region of Toscana.

- Val di Magra (Bianco; Rosato; Rosso in the styles normale and Novello) produced in the province of Massa Carrara.

- Montecastelli (Bianco; Rosso in the styles normale and Novello) produced in the communes of Castelnuovo Val di Cecina, Volterra, and Pomarance in the province of Pisa.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e J. Robinson, ed. (2006). The Oxford Companion to Wine (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-860990-6.

- ^ Johnson, H. (1989). Vintage: The Story of Wine. Simon & Schuster. pp. 416–420. ISBN 0-671-68702-6.

- ^ a b c M. Ewing-Mulligan; E. McCarthy (2001). Italian Wines for Dummies. Hungry Minds. pp. 142–145. ISBN 0-7645-5355-0.

- ^ a b O'Keefe, Kerin (2009). "Rebels without a cause? The demise of Super-Tuscans" (PDF). The World of Fine Wine (23): 94–99.

- ^ a b M. Ewing-Mulligan & E. McCarthy Italian Wines for Dummies pg 155 & 167-169 Hungry Minds 2001 ISBN 0-7645-5355-0

- ^ a b c d e M. Ewing-Mulligan & E. McCarthy Italian Wines for Dummies pg 156-163 Hungry Minds 2001 ISBN 0-7645-5355-0

- ^ "Production Policy Document". vinivaldichianatoscana.it. Consorzio Vini Valdichiana Toscana. Retrieved 2019-12-19.

- ^ a b c d e M. Ewing-Mulligan & E. McCarthy Italian Wines for Dummies pg 164-174 Hungry Minds 2001 ISBN 0-7645-5355-0

- ^ MacNeil, K. (2001). The Wine Bible. Workman Publishing. pp. 376, 386–387. ISBN 1-56305-434-5.

- ^ a b c M. Ewing-Mulligan & E. McCarthy Italian Wines for Dummies pg 147-155 Hungry Minds 2001 ISBN 0-7645-5355-0

- ^ wine-searcher.com

- ^ "The winery". fattoriasantavittoria.com. Fattoria Santa Vittoria Winery and Farm. Retrieved 2019-12-19.

- ^ Decreto Ministeriale, 5 August 1996

External links

[edit]- "Are Super-Tuscans Still Super?" Food and Wine Magazine, Dec. 2006

- "Rebels without a cause? The demise of Super-Tuscans" The World of Fine Wine, Issue 23 2009

- "Are Super-Tuscans Still Super?" The New York Times, April 13, 2009

Tuscan wine

View on GrokipediaHistory

Ancient and Medieval Periods

The origins of viticulture in Tuscany trace back to the Etruscan civilization, which flourished from the 8th to 3rd centuries BCE, with archaeological evidence indicating early grape cultivation particularly in coastal and southern areas such as the Maremma region and the Albegna River valley near Grosseto.[6] Etruscan winemaking is attested through the production of ceramic amphorae for wine storage and transport, with industrial-scale manufacturing emerging as early as the 7th century BCE, facilitating exports to regions like southern Gaul via Mediterranean trade networks.[7] These amphorae, often found in shipwrecks and archaeological sites, underscore the Etruscans' role in establishing foundational viticultural practices in the region, blending indigenous experimentation with influences from Phoenician and Greek techniques.[8] Roman expansion into Etruria beginning in the 3rd century BCE marked a shift toward systematic viticulture, as Roman settlers integrated and expanded upon Etruscan traditions, introducing advanced vineyard management practices like trellising and soil preparation in areas such as Chianti.[9] This period also saw the propagation of existing grape varieties, including early forms of Sangiovese, enhancing the diversity and quality of Tuscan wines through selective cultivation across the peninsula.[10] The Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder noted in his Natural History (Book 14) that certain vines, such as the bee-vine, flourished particularly well in Tuscan soils.[11] During the medieval period from the 9th to 14th centuries, Benedictine and Cistercian monks played a pivotal role in preserving and refining viticultural techniques amid the post-Roman decline, establishing vineyards and cellars in key Tuscan locales like Chianti and Montalcino to support monastic self-sufficiency and liturgical needs.[12] These religious orders improved winemaking through meticulous record-keeping, selective pruning, and fermentation methods, contributing to the revival of production in hilly terrains suited to quality grapes.[13] By the 12th century, the rise of urban commerce led to the formation of wine guilds in Florence and Siena, such as the Arte dei Vinattieri in Florence, which regulated production, quality standards, and trade to meet growing demand.[14] These guilds facilitated the expansion of export networks, notably along medieval trade routes like the Via Francigena, where Vernaccia from San Gimignano was shipped northward to European markets, bolstering Tuscany's economic and cultural influence through wine.[15]Renaissance to Modern Developments

During the Renaissance, the Medici family played a pivotal role in advancing Tuscan winemaking through their patronage and establishment of vineyards on family estates such as Poggio a Caiano, where wines were produced for courtly banquets and gifted to foreign dignitaries.[16] In 1716, Grand Duke Cosimo III de' Medici issued an edict delineating the boundaries of key wine production zones, including Chianti, which formalized quality standards and elevated Tuscan wines' reputation across Europe.[17] This period from the 15th to 18th centuries saw growing exports of Tuscan wines, particularly Chianti, to England and northern European markets, driven by the region's agricultural renaissance and increasing demand for robust reds.[18] The late 19th century brought devastation to Tuscan vineyards with the phylloxera outbreak, which arrived in Italy around 1879 and rapidly spread through Tuscany by the 1890s, devastating many of the region's vineyards and causing widespread economic hardship for growers. Recovery involved replanting with phylloxera-resistant American rootstocks, such as Vitis riparia and Vitis berlandieri hybrids, grafted to European varieties like Sangiovese, a process that began in earnest in the 1880s and fundamentally altered grape selection by favoring more resilient clones.[19] These changes shifted Tuscan viticulture toward denser plantings and selective breeding, setting the stage for modern quality improvements. Early 20th-century regulations aimed to standardize production amid post-phylloxera recovery; in 1932, a ministerial decree established the Chianti denomination, dividing it into seven sub-zones including Classico, to protect authenticity and control yields.[18] In 1963, Chianti became one of Italy's first DOC wines, followed by the establishment of additional DOCs and the first DOCGs in the 1980s, such as Vino Nobile di Montepulciano in 1980, formalizing quality standards for Tuscan wines. Following World War II, Tuscan winemaking underwent significant modernization in the 1950s and 1960s, with the introduction of mechanized harvesting and processing equipment that boosted efficiency and reduced labor costs in hilly terrains.[20] The rise of cooperative wineries, numbering over 148 by 1950 and expanding to produce 18% of Italy's wine by 1970, enabled smallholders to access shared technology and markets, fostering collective quality control.[21] In the 1960s and 1970s, quality-focused estates like Marchesi Antinori emerged as leaders in innovation, with Piero Antinori assuming control in the mid-1960s and experimenting with international varieties and barrique aging to elevate Sangiovese-based wines beyond traditional constraints.[22] A key advancement was the 1970s adoption of stainless steel fermentation tanks in Tuscan cellars, which allowed precise temperature control during Sangiovese vinification, preserving fruit clarity and reducing oxidative flaws for crisper, more vibrant reds.[23] These developments propelled Tuscan wines toward global acclaim by the 1980s, blending heritage with technological precision.[4]Geography and Climate

Landscape and Terroir

Tuscany's landscape is characterized by a diverse topography that profoundly influences its viticultural terroir. In the east, the Apennine Mountains form a rugged barrier, rising to elevations over 1,000 meters and creating sheltered valleys ideal for vine cultivation at lower altitudes. The central region features iconic rolling hills, such as those in the Chianti area, where vineyards are planted on undulating terrain between 200 and 500 meters above sea level, promoting optimal sun exposure and natural drainage. To the west, coastal plains extend along the Tyrrhenian Sea, including the Maremma district, where flatter lands at elevations as low as 100 meters benefit from moderating maritime breezes that temper heat and enhance vine resilience.[24][2][25] Soil compositions across Tuscany vary significantly, contributing to the region's unique growing conditions for vines. In the Chianti zone, galestro—a crumbly, schist-like marl—and alberese, a compact limestone formation, dominate, allowing roots to penetrate deeply up to several meters for water and nutrients while ensuring excellent drainage to prevent waterlogging. Montalcino's terroir features clay-limestone soils that retain moisture during dry periods, supporting robust vine growth at elevations from 150 to 450 meters. Bolgheri's coastal vineyards thrive on sandy alluvial deposits, which provide loose, well-aerated conditions for heat-loving varieties, while near San Gimignano, volcanic tuff and clay-rich soils impart minerality and structure, with elevations reaching 300 to 500 meters. In the Maremma, maritime influences from the nearby sea moderate temperatures and humidity, fostering balanced ripening on these varied substrates.[26][27][28][2][29][30] As of 2024, Tuscany boasts over 61,000 hectares under vine, with these terrain and soil features enabling deep-rooted vines like Sangiovese to adapt to the rocky, fragmented ground, enhancing concentration and complexity in the resulting wines. The elevation range of 100 to 600 meters further shapes terroir by influencing diurnal temperature shifts, with higher sites offering cooler nights for acidity preservation and lower coastal areas providing warmth for full phenolic ripeness.[31][2][32][33]Climatic Influences

Tuscany's wine regions are characterized by a Mediterranean climate, featuring hot, dry summers with average daytime temperatures ranging from 25°C to 30°C and mild winters where temperatures rarely drop below freezing.[34] This climate supports the slow maturation of grapes, particularly Sangiovese, by providing ample sunlight—over 2,000 hours annually—while the mild winters allow vines to enter dormancy without severe frost damage in most areas.[33] Annual rainfall typically falls between 600 and 800 mm, concentrated primarily in spring and autumn, which replenishes soil moisture without excessive humidity that could foster diseases during the growing season.[34][35] Microclimatic variations across Tuscany significantly influence vine health and wine profiles, with the hilly interior of Chianti experiencing cooler nights that preserve acidity in grapes, contributing to the bright, structured wines of the region.[36] In contrast, the coastal areas around Bolgheri benefit from warmer conditions that facilitate the full ripening of international varieties like Cabernet Sauvignon, resulting in fuller-bodied reds with ripe tannins.[37] Sea breezes from the Tyrrhenian Sea play a crucial role in moderating these temperatures, cooling daytime highs and reducing humidity, which helps prevent overheating and supports balanced phenolic development in the berries.[38] However, challenges such as summer droughts and hailstorms pose risks; prolonged dry spells can stress vines, leading to reduced yields, while sudden hail events damage clusters, as seen in various growing seasons.[39] The growing season in Tuscany generally spans from April, when bud break occurs amid rising temperatures, to October, when harvest concludes for most red varieties.[40] In the 2020s, broader Mediterranean warming trends have led to consistently warmer vintages, with summers like 2022 marking the hottest and driest on record, accelerating ripening and yielding concentrated wines with elevated alcohol levels.[36] Similarly, 2021 featured hot, dry conditions up to 39°C in parts of Montalcino, though coastal breezes mitigated extremes in Bolgheri, preserving freshness in the resulting vintages.[36] These shifts, driven by rising average temperatures, underscore the evolving atmospheric pressures on Tuscan viticulture, where terrain amplifies local effects like diurnal swings.[41]Grape Varieties

Indigenous Grapes

Tuscany's indigenous grape varieties form the backbone of its winemaking tradition, with red grapes dominating the region's plantings at approximately 85% of total vineyard area.[42] Among these, Sangiovese stands as the preeminent variety, accounting for over 60% of all Tuscan grape plantings and representing a cornerstone of historical blends like those in Chianti.[1] Genetic analysis has revealed Sangiovese's origins as a natural cross between Ciliegiolo and the rare Calabrese di Montenuovo, linking it to ancient southern Italian varieties and underscoring its deep-rooted heritage in the peninsula.[43] Sangiovese is prized for its high acidity, moderate tannins, and flavors of red cherry, alongside notes of floral and spicy undertones that vary with terroir, making it highly sensitive to soil and climate influences across Tuscany's diverse landscapes.[44] This adaptability has sustained its role as the primary grape in traditional Tuscan reds, where it provides structure and longevity.[45] Notable clones include Brunello, used exclusively in Montalcino wines for its concentrated fruit and robust structure, and Prugnolo Gentile, a finer-skinned variant that contributes elegance and plum-like aromas to Montepulciano blends.[46] As of 2024, Sangiovese covers approximately 70,000 hectares nationwide in Italy, with the majority in Tuscany.[47] Complementing Sangiovese in traditional red blends are several supporting indigenous varieties that enhance balance and complexity. Canaiolo, with its softer tannins, lower acidity, and fruit-forward profile of red berries and herbs, serves as a key softening agent in Chianti formulations, historically mitigating Sangiovese's austerity.[48] Mammolo adds aromatic depth through violet and spicy floral notes, contributing elegance and perfume to blends while maintaining good acidity for freshness.[49] Colorino, known for its thick skins and high pigmentation, functions primarily as a color enhancer, imparting deep ruby hues and firm tannins without overpowering fruit expression.[50] Tuscan white indigenous grapes, though less prevalent, play vital roles in both dry and sweet styles, often in high-yield blending scenarios. Trebbiano Toscano, the most planted white variety in the region, offers a neutral profile with crisp acidity, subtle green apple notes, and high productivity, making it ideal for base wines and historical field blends.[51] Malvasia Bianca Lunga brings floral aromas of white flowers and citrus peel, along with a touch of sweetness, and is essential in Vin Santo production for its ability to develop rich, oxidative honeyed qualities during appassimento.[52] Vernaccia di San Gimignano, with its bright citrus flavors, mineral salinity, and almond-like finish, stands out for structured dry whites, reflecting its ancient Etruscan ties and adaptability to hillside terroirs.[53]International and Blended Varieties

In the late 20th century, Tuscan winemakers began incorporating international grape varieties, primarily inspired by Bordeaux influences, to diversify and enhance their wines. This shift gained momentum in the 1970s, with pioneers like Marchese Mario Incisa della Rocchetta planting Cabernet Sauvignon at Tenuta San Guido in 1944, though commercial production of blends like Sassicaia emerged in the 1960s and 1970s. Similarly, in 1971, Piero Antinori released Tignanello, blending Sangiovese with Cabernet Sauvignon and Cabernet Franc, challenging traditional regulations and sparking the Super Tuscan movement. These imports addressed limitations in native varieties by introducing grapes suited to Tuscany's evolving terroir, particularly in response to warmer climates.[54][55][56] Key international varieties have since become integral to Tuscan viticulture, with Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot providing bold structure, deep color, and softer tannins that complement Sangiovese in Super Tuscan-style wines. Syrah contributes spicy, peppery notes, particularly in warmer southern areas like Maremma, while Cabernet Franc adds herbal and aromatic complexity, often shining in coastal zones such as Bolgheri. These grapes now represent a significant portion of Tuscany's vineyard landscape, with international varieties accounting for approximately 15-20% of total plantings as of recent assessments—Merlot at around 8%, Cabernet Sauvignon at 6%, Syrah at 2%, and Cabernet Franc at 1.3%. Their adoption has broadened winemaking options, allowing for more robust, age-worthy reds that appeal to global markets.[57][1][2] Blending practices in Tuscany frequently involve 20% or more of these international varieties in IGT-designated wines to enhance the structure and fruitiness of Sangiovese-based blends, creating fuller-bodied profiles with improved balance. A prime example is Sassicaia, which typically comprises 85% Cabernet Sauvignon and 15% Cabernet Franc, offering intense black fruit and elegance without Sangiovese. Regulations in select DOC appellations, such as Bolgheri DOC established in 1994, explicitly permit these Bordeaux-style blends, while others like Chianti allow limited inclusions (up to 20% non-native reds) to maintain typicity. In coastal areas, these varieties benefit from moderated maritime climates, ripening earlier and more evenly than some late-maturing natives, which helps preserve acidity amid rising temperatures.[58][59][60]Wine Regions

Chianti

Chianti is Tuscany's largest and most iconic wine appellation, encompassing a vast area in the central hills between Florence and Siena. The production zone spans approximately 100,000 hectares, with the historic core known as Chianti Classico covering about 72,000 hectares subdivided into 11 Unità Geografiche Aggiuntive (UGAs) for greater terroir specificity.[61] Chianti Classico itself includes around 7,000 hectares of vineyards, making it the heartland of the denomination. The broader Chianti DOCG includes additional subzones such as Colli Aretini, Colli Senesi, Colli Fiorentini, Colline Lucchesi, Montalbano, and Rufina, each contributing to the region's diverse expressions.[62] The appellation received DOC status in 1963, a pivotal upgrade that formalized production standards and elevated Chianti's global reputation amid post-World War II challenges.[18] The terroir of Chianti is characterized by rolling hills at elevations between 200 and 500 meters, where galestro—a fractured, schistous clay soil—predominates, offering excellent drainage and mineral-driven complexity to the wines. These conditions, combined with a continental climate of warm days and cool nights, stress the vines to produce concentrated flavors. Key historic producers like Castello di Brolio, owned by the Ricasoli family since 1141, have shaped the region's legacy; Baron Bettino Ricasoli developed the foundational "formula" for Chianti in 1872, emphasizing Sangiovese as the dominant grape. Ruffino, founded in 1877 by cousins Ilario and Leopoldo Ruffino in Pontassieve, became a pioneering exporter of Chianti, blending tradition with innovation to popularize the wine internationally.[63][27][64][65] Regulations for Chianti Classico wines mandate at least 80% Sangiovese, with the remainder from approved local red grapes like Canaiolo Nero; other Chianti DOCG subzones require a minimum of 70% Sangiovese, allowing for elegant, structured reds that reflect the grape's dominance in Tuscan viticulture. Chianti Classico wines are typically medium-bodied with aromas of red cherry, violet, and herbs, balanced acidity, firm tannins, and alcohol levels of 12-13% ABV, offering versatility for aging or immediate enjoyment. The Riserva category requires a minimum of 24 months aging, including three months in bottle, resulting in deeper, more integrated flavors with softened tannins and enhanced complexity. Annual production hovers around 250,000 hectoliters, underscoring Chianti's scale as Tuscany's flagship appellation.[66][62][67][68] The black rooster (Gallo Nero) serves as the enduring symbol of Chianti Classico, originating from a 13th-century legend where a starved black rooster from Florence crowed at dawn, granting Florentine forces an early advantage in a border dispute with Siena and establishing the region's boundaries. Adopted by the Lega del Chianti military league in the 14th century, the emblem now adorns certified bottles, representing authenticity and heritage.[69]Brunello di Montalcino

Brunello di Montalcino is a renowned red wine from the rolling hills surrounding the town of Montalcino in southern Tuscany, Italy, encompassing approximately 3,500 hectares of registered vineyards within the municipality's historical boundaries.[70] This DOCG appellation, established in 1980 as one of Italy's inaugural protected designations, mandates production exclusively from the Sangiovese Grosso clone, locally termed Brunello, harvested at a maximum yield of 8 tons per hectare to ensure concentration and quality.[71][72] The wine's origins trace to the late 19th century, pioneered by the Biondi-Santi family; Ferruccio Biondi-Santi produced the first commercial vintage in 1888, selecting for a robust, age-worthy expression of the grape that defined the style. Strict regulations govern aging to develop the wine's structure: standard Brunello requires a minimum of 4 years maturation, including at least 2 years in oak barrels and 4 months in bottle, with release permitted on January 1 of the fifth year following harvest; Riserva variants extend this to 5 years total, with 6 months in bottle.[71] These rules emphasize traditional methods, yielding a minimum alcohol content of 12.5% and fostering a wine known for its longevity, often aging 10 to 30 years or more under proper conditions.[72] Annual output typically reaches around 8 to 9 million bottles; for the 2025 vintage, harvested in early October under favorable conditions, production was approximately 7.5 million bottles due to a mild yield reduction while quality remained high.[73][74] The terroir of Montalcino varies significantly, influencing the wine's profile: southern slopes feature clay-rich soils at elevations of 150 to 300 meters, promoting powerful, tannic expressions, while northern areas have limestone and galestro marls at 300 to 500 meters, yielding more elegant, mineral-driven wines.[75] Gentle maritime breezes from the nearby Tyrrhenian Sea temper the Mediterranean climate, providing diurnal temperature shifts that preserve acidity and enhance phenolic balance in the Sangiovese Grosso berries.[76] Brunello di Montalcino exhibits a deep ruby hue, with aromas of ripe dark fruits like black cherry and plum, layered with notes of tobacco, leather, and underbrush; on the palate, it delivers firm, grippy tannins, vibrant acidity, and a persistent finish that evolves into tertiary flavors of balsamic and spice with extended aging.[72] Riserva bottlings amplify this intensity, often showing greater depth and refinement after additional barrel time.[71]Vino Nobile di Montepulciano

Vino Nobile di Montepulciano is a prestigious red wine produced exclusively in the hilly territory surrounding the town of Montepulciano in southeastern Tuscany, near Siena. Recognized as a Denominazione di Origine Controllata (DOC) in 1966 and elevated to DOCG status in 1980, it represents one of Italy's classic expressions of Sangiovese-based winemaking, emphasizing elegance and longevity. The denomination covers approximately 1,200 hectares of vineyards, yielding around 50,000 hectoliters annually, as recorded for the 2024 vintage with 6.7 million bottles produced from 8,850 tons of grapes.[77] The production zone is confined to the administrative boundaries of Montepulciano, spanning a landscape of rolling hills at elevations between 250 and 600 meters above sea level. This inland location in eastern Tuscany contributes to a cooler continental climate with significant diurnal temperature variations, fostering balanced acidity and structural depth in the wines. The terroir features predominantly sandy clay soils enriched with Pliocene-era fossils and pebbles, known locally for their loose structure that promotes good drainage while retaining sufficient moisture for vine health. These conditions, often referred to as conchiglie due to the fossil shell content, impart minerality and finesse to the resulting wines.[77][78] By regulation, Vino Nobile must comprise at least 70% Prugnolo Gentile, a local clone of Sangiovese prized for its aromatic intensity and resilience, blended with up to 30% other authorized Tuscan red varieties such as Canaiolo Nero and Mammolo for added complexity and softness. The wines exhibit an elegant profile with aromas of violet, ripe cherry, plum, and subtle red berry notes, underpinned by firm yet integrated tannins, vibrant acidity, and hints of tea leaf or dried herbs. A minimum aging period of two years is required, including at least one year in oak, ensuring approachability after release while allowing for extended cellaring potential up to 10-15 years or more.[77][78][78] Prominent estates like Avignonesi, a leading biodynamic producer with historic vineyards in the zone, and Contucci, a family-owned winery dating back to the 18th century, exemplify the denomination's commitment to quality and tradition. These properties highlight the wine's evolution from Renaissance-era noble beverage to a modern benchmark of Tuscan excellence.Bolgheri

Bolgheri is situated on the Maremma coast in the province of Livorno, Tuscany, encompassing approximately 1,300 hectares of vineyards within the municipality of Castagneto Carducci.[79][80] This coastal area stretches about 13 kilometers north-south and 7 kilometers east-west, with elevations ranging from 10 to 380 meters above sea level, excluding the immediate coastal strip west of the Via Aurelia.[79] The Bolgheri DOC was established in 1980, initially for white and rosé wines, but regulations expanded in 1994 to include the region's renowned red wines, recognizing its pioneering role in the Super Tuscan movement.[81][82] The area's winemaking heritage traces back to the 1940s when Marchese Mario Incisa della Rocchetta planted Cabernet Sauvignon and Cabernet Franc at Tenuta San Guido, leading to the first Sassicaia vintage in 1968, released commercially in 1972 and hailed as a game-changer for Italian wine.[82] This innovation, alongside the influence of Antinori's Tignanello from nearby Chianti—introduced in 1971 as a Cabernet-Sangiovese blend—spurred Bolgheri's shift toward international varieties and Bordeaux-style blends, challenging traditional Tuscan norms.[83][84] The terroir of Bolgheri features diverse soils of marine and alluvial origin, primarily sandy clay loams that are alkaline, deep, and enriched with fine gravel, fossilized shells, and marine deposits from ancient seabeds.[79] These gravelly, well-draining soils, combined with a mild maritime climate moderated by Tyrrhenian Sea breezes and protective Colline Metallifere hills, provide ideal conditions for ripening international red varieties like Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot.[79] The climate averages 15.5°C annually, with about 600 mm of precipitation, frequent winds on roughly 250 days per year, and ample sunlight, fostering balanced acidity and concentrated fruit flavors while mitigating frost and excessive heat.[79] Subzones such as the Sassicaia area, limited to 75 hectares around Tenuta San Guido, exemplify this with particularly stony, gravel-dominant soils suited to Cabernet blends.[85] Bolgheri produces bold, structured red wines under DOC designations like Bolgheri Rosso, Bolgheri Superiore, and the exclusive Bolgheri Sassicaia, primarily from Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, and Cabernet Franc, with allowable additions of Syrah, Petit Verdot, or minimal Sangiovese.[86] Sassicaia, the flagship example, typically comprises 85% Cabernet Sauvignon and 15% Cabernet Franc, yielding opulent wines with dark berry, balsamic, and herbal notes, firm tannins, and excellent aging potential after 24 months of aging, including 18 in barriques.[85][86] Bolgheri is also home to other iconic Super Tuscans such as Ornellaia and Masseto, which, together with Sassicaia, are often regarded as part of the "big five" most prestigious examples of the category (along with Solaia and Tignanello from the Chianti area).[87][88] White wines, such as Vermentino-based examples, offer fresh, mineral-driven profiles with citrus and herbal aromas, reflecting the terroir's coastal freshness.[86] By 2025, the region has grown to support annual production of around 80,000 hectoliters, driven by 75 consortium members managing nearly all vineyards, underscoring Bolgheri's evolution into a global benchmark for modern Tuscan reds.[89][90]Vernaccia di San Gimignano

Vernaccia di San Gimignano is a renowned white wine appellation located in the hilly terrain of the municipality of San Gimignano, in the northern part of Tuscany's Siena province. The production zone encompasses approximately 700 hectares of vineyards, primarily dedicated to the indigenous Vernaccia grape variety, which forms the backbone of Tuscany's white wine heritage. Established as Italy's first Denominazione di Origine Controllata (DOC) in 1966 and elevated to Denominazione di Origine Controllata e Garantita (DOCG) status in 1993, the appellation requires at least 85% Vernaccia in the blend, with the remainder from other approved non-aromatic white grapes such as up to 15% regional varieties or 10% Sauvignon and Riesling. This strict regulation ensures the wine's distinctive character, rooted in the area's medieval viticultural legacy, where Vernaccia was a prized export by the 13th century, taxed for trade outside the town and even requested in bulk for noble events like the 1468 wedding of Ludovico il Moro. Its fame reached literary heights in Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy (Canto XXIV), where the poet references the wine in association with Pope Martin IV's gluttony, underscoring its historical prestige as a symbol of Tuscan excellence.[91][92][93][91][91] The terroir of San Gimignano plays a pivotal role in shaping the wine's profile, featuring Pliocene-era soils of yellow sand (tufa) and clay over blue clay subsoils, which are well-drained and low in organic matter, imparting a savory, mineral quality. These volcanic-influenced soils, combined with hillside elevations typically between 200 and 400 meters (up to 500 meters), contribute to optimal drainage and sun exposure. The sub-Mediterranean climate is dry and temperate, with annual rainfall of 600-700 mm concentrated in autumn and spring, temperatures ranging from -5°C to 37°C, and consistent ventilation that minimizes frost and humidity risks, fostering the development of crisp, aromatic whites. This environment, with its varied microclimates from the hill system's exposures, enhances the Vernaccia grape's expression, yielding grapes with balanced acidity and concentrated flavors.[94][94][94] Vernaccia di San Gimignano wines are characterized by a straw-yellow hue with golden reflections, offering aromas of citrus, white flowers, and green apple, evolving into mineral and spicy notes with age. On the palate, they deliver a dry, harmonious structure with lively acidity, subtle bitterness, and a distinctive almond aftertaste, making them elegant and versatile. Production adheres to a maximum yield of 9 tons per hectare, resulting in an average annual output of around 35,000 hectoliters in recent years, such as 35,600 hectoliters in 2023. Variants include the standard DOCG and Riserva (aged at least 11 months with 3 months in bottle, minimum 12% alcohol), as well as sparkling versions produced via the metodo classico from select Vernaccia and Chardonnay blends, adding effervescence and finesse; passito styles, made from dried grapes, offer richer, honeyed expressions though less common. These traits highlight the wine's adaptability, from fresh aperitifs to aged expressions revealing flinty depth.[95][96][97][92][98][93][99]Carmignano

Carmignano is a historic wine appellation located in northwestern Tuscany, encompassing the hilly areas around the communes of Carmignano and Poggio a Caiano, near Prato, with vineyards spanning approximately 150 hectares.[100] This region holds a pioneering place in Tuscan viticulture, as it was one of the first areas officially delimited for quality wine production by Grand Duke Cosimo III de' Medici through his 1716 Motu Proprio decree, which recognized Carmignano alongside Chianti, Pomino, and Val d'Arno di Sopra as premier wine zones and implicitly permitted the blending of local Sangiovese with Cabernet varieties introduced earlier by the Medici family in the 16th century.[101] The decree marked an early form of controlled origin designation, emphasizing the area's suitability for structured reds, and the tradition of incorporating Cabernet—traced back to Catherine de' Medici's influence—sets Carmignano apart as Tuscany's original hybrid of indigenous and international grapes.[102] The Carmignano DOCG, elevated from DOC status in 1975 to DOCG in 1990 (retroactive to the 1988 vintage), mandates a blend dominated by Sangiovese at a minimum of 50%, with 10-20% Cabernet Sauvignon and/or Cabernet Franc, up to 20% Canaiolo Nero, and no more than 10% other authorized varieties like Malvasia or Trebbiano for the base Rosso.[103][104] The terroir features hillside vineyards at 250-400 meters elevation on the eastern slopes of the Montalbano range, close to the Apennines, where clay-loam soils rich in calcareous marl (galestro) and sandstone provide excellent drainage and mineral depth, while the proximity to mountains imparts diurnal temperature swings and fresh breezes that preserve acidity and aromatic freshness in the grapes.[105][26] Carmignano wines are predominantly structured reds known for their balance of Sangiovese's cherry and herbal notes with Cabernet's cassis and spice, yielding elegant, age-worthy expressions with underlying earthiness from the terroir. The base Carmignano requires at least 8 months in oak and release after 20 months total aging, while the Riserva demands 3 years minimum, including 20 months in barrel, enhancing complexity with notes of leather and tobacco. Annual production remains small, around 2,700 hectoliters, reflecting the region's boutique scale and commitment to quality over volume.[100][106]Other Regions

Beyond the prominent appellations, Tuscany's wine landscape includes several lesser-known regions that contribute distinctive styles, often emphasizing local terroirs and innovative blends. These areas, ranging from northern hillsides to southern coastal plains, showcase a diversity of grapes and soils, fostering both traditional and experimental wines that complement the region's Sangiovese-dominated heritage.[107] In the northern part of Tuscany near Lucca, the Montecarlo DOC occupies hillside vineyards at elevations of 100 to 500 meters, benefiting from a Mediterranean climate moderated by proximity to the Tyrrhenian Sea. This denomination specializes in white wines, where Bianco must comprise at least 60% Trebbiano Toscano blended with varieties such as Sauvignon Blanc, Vermentino, or Sémillon, yielding crisp, aromatic expressions with citrus and herbal notes. Red wines, labeled Rosso, require 50-75% Sangiovese supplemented by Canaiolo Nero, Merlot, or Syrah, producing balanced, fruit-forward reds suited to the area's clay-limestone soils. Established in 1969, Montecarlo represents Tuscany's shift toward international white varietals in a traditionally red-focused region.[107][108] Further south, the Maremma Toscana DOC encompasses coastal and inland zones in the province of Grosseto, where sandy, alluvial, and volcanic soils support a range of reds and whites since its elevation from IGT status in 2011. This emerging area, revitalized in the 1990s through pioneering plantings of international grapes, features Vermentino as a flagship white, requiring at least 85% of the variety for varietal wines that highlight mineral-driven, saline profiles from maritime influences. Syrah thrives here in reds, comprising at least 85% for single-varietal bottlings or blending into Rosso (minimum 60% Sangiovese base), offering spicy, structured wines reflective of the warm, breezy microclimate. Vineyard surface spans approximately 2,364 hectares as of 2022, with ongoing expansion driven by demand for Mediterranean-style varieties like Ciliegiolo and Ansonica.[109][110] A notable DOCG within the Maremma area is Morellino di Scansano, covering about 2,000 hectares of vineyards in the hills around Scansano. Established as DOCG in 2007, it focuses on reds with at least 85% Sangiovese (locally Morellino), blended with up to 15% other authorized varieties, producing vibrant, cherry-scented wines with soft tannins suited to the area's schistous and sandstone soils and mild coastal climate. Annual production exceeds 100,000 hectoliters, highlighting its role in southern Tuscan viticulture.[111][112] The Val d'Arbia DOC, located in the Siena province amid rolling hills of the Arbia River valley, focuses primarily on white wines from at least 70% Trebbiano Toscano and Malvasia Bianca Lunga, with allowances for Chardonnay or Vermentino up to 30%, resulting in fresh, floral styles including varietal expressions and Vin Santo dessert wines. Nearby, the Valdichiana Toscana DOC in the Arezzo area, part of the historic Etruscan plains south of the city, permits experimental red blends under its Rosso designation, mandating a minimum 50% Sangiovese augmented by Cabernet Franc, Merlot, or Ciliegiolo for robust, age-worthy wines suited to the fertile, alluvial soils. These denominations trace roots to ancient viticulture practices in central Tuscany's plains, enabling innovative IGT-style flexibility within DOC frameworks for lesser-known blends.[113][114][115] Among niche contributions, the Orcia DOC in the Val d'Orcia southeast of Siena produces Sangiovese-based reds requiring at least 60% of the variety, often blended with Canaiolo or international grapes, to create elegant, cherry-scented wines that capture the UNESCO-protected landscape's volcanic and clay soils. Promoted to DOC in 2000, Orcia emphasizes sustainable farming and terroir-driven expressions, with varietal Sangiovese bottlings highlighting the area's thermal springs and dramatic topography for structured, food-friendly reds.[116][117]Wine Styles

Traditional Red Wines

Traditional red wines of Tuscany are predominantly based on the Sangiovese grape, which forms the backbone of iconic appellations such as Chianti Classico and Brunello di Montalcino. These wines adhere to longstanding production regulations that emphasize the purity and structure of Sangiovese, typically requiring a minimum of 80% for Chianti Classico and 100% for Brunello di Montalcino.[118][119] The winemaking process begins with hand-harvested grapes fermented in temperature-controlled stainless steel or concrete vats, followed by extended maceration on the skins for 15 to 30 days to extract deep color, robust tannins, and complex flavors.[120][121] This stage is crucial for developing the wines' characteristic intensity, after which the must is pressed and undergoes malolactic fermentation. Aging occurs traditionally in large Slavonian oak barrels (botte), which impart subtle oak influences without overpowering the fruit, typically resulting in alcohol levels of 12-14% ABV.[122][123] Chianti Classico exemplifies the bright, versatile profile of traditional Tuscan reds, featuring lively acidity, notes of red cherry, and herbal undertones that reflect Sangiovese's elegance.[124] In contrast, Brunello di Montalcino delivers greater power and concentration, with flavors of ripe plum, leather, and spice emerging from its extended aging requirements of at least four years, including two in oak.[125] Both wines exhibit excellent aging potential, with Chianti Classico suitable for 5-10 years of cellaring and Brunello capable of evolving over 10-20 years, developing tertiary notes of earth and dried fruit.[126] The 2025 vintage, marked by favorable weather conditions leading to healthy grapes and balanced ripeness, has produced traditional reds with enhanced harmony between acidity, tannin, and fruit, promising refined structure for future releases.[127] These wines hold a central place in Tuscan culture, often paired with hearty local dishes like bistecca alla fiorentina, where their firm tannins and acidity cut through the steak's richness while complementing its charred flavors.[128] Chianti's export history dates to the 18th century, following its designation as the world's first demarcated wine region in 1716 by Grand Duke Cosimo III de' Medici, which spurred international trade and established it as a symbol of Tuscan heritage.[129] Brunello followed suit in the late 19th century, gaining global acclaim through exports that now account for a significant portion of Tuscany's wine trade, underscoring the enduring appeal of these Sangiovese-driven classics.[130]Super Tuscans

Super Tuscans emerged in the 1970s as a revolutionary response to the rigid regulations of the Chianti DOC, which mandated the inclusion of white grape varieties and limited the use of non-traditional reds, stifling innovation among ambitious producers.[59] Frustrated winemakers began experimenting with international grape varieties and modern techniques to craft higher-quality wines, bypassing appellation rules by labeling their creations as simple Vino da Tavola.[56] The prototype was Sassicaia, produced at Tenuta San Guido by Marchese Mario Incisa della Rocchetta, with its first vintage in 1968 and commercial release in 1971; inspired by Bordeaux, it featured Cabernet Sauvignon planted as early as 1944 and marked a shift toward premium, age-worthy reds.[59] This rebellion not only elevated Tuscan wine's global reputation but also pressured regulators to reform, culminating in the introduction of the IGT Toscana category in 1992 to accommodate such innovative wines.[131] Production of Super Tuscans emphasizes meticulous viticulture and winemaking to achieve concentration and complexity, typically involving low yields—around 40-45 hectoliters per hectare for Sassicaia—to enhance flavor intensity.[132] Grapes are often fermented in small stainless steel or open-top wooden vats for 15-25 days, followed by aging for 18-24 months in small French oak barriques (225 liters), which impart structure, vanilla, and spice notes while softening tannins.[59] Blends commonly incorporate international varieties such as Cabernet Sauvignon alongside Sangiovese, for example, early vintages like Tignanello featuring approximately 80% Sangiovese blended with around 15-20% Cabernet Sauvignon (and initially small amounts of white grapes), though compositions vary by producer and vintage.[133] These methods, a stark departure from traditional large Slavonian oak aging, allowed for opulent wines that rivaled top Bordeaux.[56] Characterized by their full-bodied opulence, Super Tuscans exhibit deep ruby colors, aromas of blackcurrant, blackberry, graphite, and spice, with firm yet integrated tannins and impressive aging potential of 10-20 years or more.[59] Their premium status is reflected in high prices, ranging from $50 for entry-level expressions to $500 or more for top vintages of icons like Sassicaia.[56] Initially confined to IGT Toscana status, many have since gained dedicated DOC designations, such as the Bolgheri Sassicaia DOC established in 1994 exclusively for Sassicaia reds.[56] In 2025, Ornellaia remains a benchmark Super Tuscan, its Bordeaux-style blend of Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot from Bolgheri continuing to exemplify the category's enduring prestige and quality evolution.[131] The most consistently acclaimed Super Tuscan wines are subjective and vary by vintage and critic, but the most prominent and frequently cited examples—often referred to as the "big five"—are Sassicaia, Tignanello, Ornellaia, Masseto, and Solaia. These wines are widely recognized as the icons of the category due to their historical influence, brand strength, and quality.[87] Recent tastings reported by James Suckling in 2025 have highlighted exceptional "wow" factors in certain releases, including Solaia, Flaccianello della Pieve, and Girolamo, praised for their precision, finesse, depth, and complexity.[134]White and Dessert Wines

Tuscan white wines, though less prominent than the region's renowned reds, offer crisp, refreshing profiles suited to the Mediterranean climate. Vernaccia di San Gimignano, Tuscany's only white DOCG, is produced primarily from the Vernaccia grape, which constitutes at least 85% of the blend, yielding a dry wine with pronounced minerality and a subtle saltiness derived from the area's galestro soils and proximity to the sea.[135][136] This variety delivers floral and citrus aromas, with notes of white peach, almond, and a tangy, harmonious finish that emphasizes its fresh acidity and food-friendly structure.[53][96] Trebbiano blends, often featuring Trebbiano Toscano as the dominant grape, produce light-bodied whites characterized by high acidity, subtle floral aromas, and flavors of green apple, lemon, and white flowers.[137][138] These wines are typically fresh and versatile, serving as everyday sippers or bases for blends that highlight Tuscany's inland terroirs. In coastal zones like Maremma, Vermentino thrives on sandy soils tolerant of sea salt, resulting in aromatic, savory whites with citrus brightness and herbal undertones that evoke the Tyrrhenian breeze.[139][140] White wines account for approximately 15% of Tuscany's total production (based on 2014 data, with recent trends showing stability), underscoring the region's red wine dominance while gaining attention for their quality in recent vintages.[2] Shifting to dessert styles, Vin Santo stands as Tuscany's iconic sweet wine, revived in prominence since the Renaissance when Florentine merchants marketed its strong, amber-hued profile.[141] Crafted via the passito method, it uses dried Trebbiano Toscano and Malvasia grapes hung in lofts for 2 to 6 months to concentrate sugars, followed by pressing and slow fermentation in small oak caratelli barrels.[142][52] The production cycle spans 3 to 5 years, including extended aging that imparts nutty, caramel, honeyed, and dried fruit notes, with alcohol levels typically ranging from 12% to 16% ABV.[143][144] Served slightly chilled at 12 to 16°C, Vin Santo pairs ideally with cantucci biscuits or blue cheeses, its oxidative richness evoking Tuscany's monastic traditions.[145][146] Beyond Vin Santo, Tuscan passito styles include rarer examples like Aleatico Passito from Elba, made from sun-dried red grapes for a luscious, berry-infused sweetness.[147] Sparkling dessert wines remain uncommon in Tuscany, where Prosecco-style alternatives are scarce compared to Veneto's offerings, though some producers experiment with metodo classico sparklers from local grapes for subtle effervescence.[148][149]Classification System

DOCG Designations

Tuscany's DOCG (Denominazione di Origine Controllata e Garantita) designations represent the pinnacle of the region's wine quality hierarchy, offering the strictest regulations to ensure authenticity, terroir expression, and excellence. These EU-protected Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) wines must adhere to rigorous production standards, including defined geographic zones, grape variety compositions, maximum yields, mandatory aging periods, and sensory evaluations by official panels to verify typicity. As of 2025, Tuscany boasts 11 DOCG categories, encompassing both red and white wines that highlight the region's Sangiovese-dominated heritage alongside unique varietals.[4][150] The DOCG system in Tuscany originated with the inaugural designations in 1980, when Brunello di Montalcino became one of Italy's first DOCG wines, swiftly followed by Vino Nobile di Montepulciano; this milestone elevated Tuscan reds to global prestige while establishing benchmarks for quality control. Regulations emphasize low yields—typically 7 to 9 tons per hectare—to concentrate flavors, alongside chemical analyses and blind tastings by consortium-appointed experts to approve only wines meeting organoleptic standards. These measures not only preserve traditional methods but also adapt to modern sustainability, ensuring DOCG wines embody Tuscany's volcanic, clay, and galestro soils.[76][72][4] Among the most iconic DOCGs, Brunello di Montalcino requires 100% Sangiovese grapes from the Montalcino commune, with a maximum yield of 8 tons per hectare and a minimum four-year aging period, including at least two years in oak barrels, to develop its structured, age-worthy profile. Chianti Classico DOCG, produced in the historic heartland spanning eight municipalities, mandates at least 80% Sangiovese with up to 20% complementary red varieties like Canaiolo or Cabernet Sauvignon; standard versions undergo a minimum 12-month aging, while yields are capped at 7.5 tons per hectare to maintain balance and intensity. Vino Nobile di Montepulciano, from the Montepulciano hills, centers on at least 70% Prugnolo Gentile (a Sangiovese clone), allowing up to 30% other approved reds, with a two-year minimum aging (one in wood) and yields limited to around 7 tons per hectare for its elegant, noble character.[72][151][152] White and specialty DOCGs add diversity, exemplified by Vernaccia di San Gimignano DOCG, which demands at least 85% Vernaccia grapes from the San Gimignano zone, with no mandatory aging for the base wine but yields controlled to preserve its crisp, mineral-driven freshness; Riserva versions require 11 months of aging. The full spectrum of Tuscany's 11 DOCGs includes:| DOCG Designation | Primary Grape(s) | Key Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Aleatico Passito dell’Elba | Aleatico (sweet red) | Dessert wine from Elba island. |

| Brunello di Montalcino | 100% Sangiovese | Iconic red; 4-year min. aging. |

| Carmignano | Sangiovese with Cabernet | Historic blend; coastal influence. |

| Chianti | Min. 70% Sangiovese | Broad zone; versatile red. |

| Chianti Classico | Min. 80% Sangiovese | Prestigious core area; Black Rooster seal. |

| Montecucco Sangiovese | Min. 90% Sangiovese | Maremma red; structured. |

| Morellino di Scansano | Min. 85% Sangiovese | Southern robust red. |

| Suvereto | Cabernet Sauvignon/Sangiovese | Bolgheri-style bold reds. |

| Val di Cornia Rosso | Sangiovese/Cabernet blends | Mineral-driven from coastal hills. |

| Vernaccia di San Gimignano | Min. 85% Vernaccia | Dry white; historic. |

| Vino Nobile di Montepulciano | Min. 70% Prugnolo Gentile | Noble red; 2-year min. aging. |

DOC and IGT Labels