Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

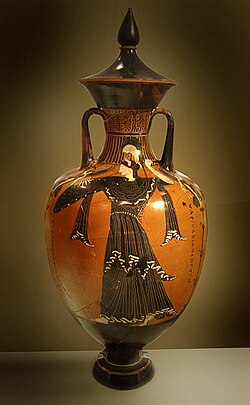

Amphora

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

An amphora (/ˈæmfərə/; Ancient Greek: ἀμφορεύς, romanized: amphoreús; English pl. amphorae or amphoras) is a type of container[1] with a pointed bottom and characteristic shape and size which fit tightly (and therefore safely) against each other in storage rooms and packages, tied together with rope and delivered by land or sea. The size and shape have been determined from at least as early as the Neolithic Period. Amphorae were used in vast numbers for the transport and storage of various products, both liquid and dry, but mostly for wine. They are most often ceramic, but examples in metals and other materials have been found. Versions of the amphorae were one of many shapes used in Ancient Greek vase painting.

The amphora complements a vase, the pithos, which makes available capacities between one-half and two and one-half tons. In contrast, the amphora holds under a half-ton, typically less than 50 kilograms (110 lb). The bodies of the two types have similar shapes. Where the pithos may have multiple small loops or lugs for fastening a rope harness, the amphora has two expansive handles joining the shoulder of the body and a long neck. The necks of pithoi are wide for scooping or bucket access. The necks of amphorae are narrow for pouring by a person holding it by the bottom and a handle. Some variants exist. The handles might not be present. The size may require two or three handlers to lift. For the most part, however, an amphora was tableware, or sat close to the table, was intended to be seen, and was finely decorated as such by master painters.[clarification needed]

Stoppers of perishable materials, which have rarely survived, were used to seal the contents. Two principal types of amphorae existed: the neck amphora, in which the neck and body meet at a sharp angle; and the one-piece amphora, in which the neck and body form a continuous curve upwards. Neck amphorae were commonly used in the early history of ancient Greece, but were gradually replaced by the one-piece type from around the 7th century BC onward.

Most were produced with a pointed base to allow upright storage by embedding in soft ground, such as sand. The base facilitated transport by ship, where the amphorae were packed upright or on their sides in as many as five staggered layers.[citation needed]. If upright, the bases probably were held by some sort of rack, and ropes passed through their handles to prevent shifting or toppling during rough seas[citation needed]. Heather and reeds might be used as packing around the vases. Racks could be used in kitchens and shops. The base also concentrated deposits from liquids with suspended solid particles, such as olive oil and wines.

Amphorae are of great use to maritime archaeologists, as they often indicate the age of a shipwreck and the geographic origin of the cargo. They are occasionally so well preserved that the original content is still present, providing information on foodstuffs and mercantile systems. Amphorae were too cheap and plentiful to return to their origin-point and so, when empty, they were broken up at their destination. At a breakage site in Rome, Testaccio, close to the Tiber, the fragments, later wetted with calcium hydroxide (calce viva), remained to create a hill now named Monte Testaccio, 45 m (148 ft) high and more than 1 kilometre in circumference.

Etymology

[edit]Amphora is a Greco-Roman word developed in ancient Greek during the Bronze Age. The Romans acquired it during the Hellenization that occurred in the Roman Republic. Cato is the first known literary person to use it. The Romans turned the Greek form into a standard - a declension noun, amphora, pl. amphorae.[2] The word and the vase were almost certainly introduced to Italy through the Greek settlements there, which traded extensively in Greek pottery.

Even though the Etruscans imported, manufactured, and exported amphorae extensively in their wine industry, and other Greek vase names were Etruscanized, no Etruscan form of the word exists. There was perhaps an as yet unidentified native Etruscan word for the vase that pre-empted the adoption of amphora.

The Latin word derived from the Greek amphoreus (ἀμφορεύς),[3] a shortened form of amphiphoreus (ἀμφιφορεύς), a compound word combining amphi- ("on both sides", "twain")[4] and phoreus ("carrier"), from pherein ("to carry"),[5] referring to the vessel's two carrying handles on opposite sides.[6] The amphora appears as 𐀀𐀠𐀡𐀩𐀸, a-pi-po-re-we, in the Linear B Bronze Age records of Knossos, 𐀀𐀡𐀩𐀸, a-po-re-we, at Mycenae, and the fragmentary ]-re-we at Pylos, designated by Ideogram 209 𐃨, Bennett's AMPHORA, which has a number of scribal variants. The two spellings are transcriptions of amphiphorēwes (plural) and amphorēwe (dual) in Mycenaean Greek from which it may be seen that the short form prevailed on the mainland. Homer uses the long form for metrical reasons, and Herodotus has the short form. Ventris and Chadwick's translation is "carried on both sides."[7]

Weights and measures

[edit]

Key : 1: rim; 2: neck; 3: handle; 4: shoulder;

5: belly or body; 6: foot

Amphorae varied greatly in height. The largest stands as tall as 1.5 metres (4.9 feet) high, while some were less than 30 centimetres (12 inches) high - the smallest were called amphoriskoi (literally "little amphorae"). Most were around 45 centimetres (18 inches) high.

There was a significant degree of standardisation in some variants; the wine amphora held a standard measure of about 39 litres (41 US qt), giving rise to the amphora quadrantal as a unit of measure in the Roman Empire. In all, approximately 66 distinct types of amphora have been identified.

Further, the term also stands for an ancient Roman unit of measurement for liquids. The volume of a Roman amphora (amphora quadrantal) was about one cubic pes (foot), equivalent to 26.2 liters (5.8 imp gal; 6.9 U.S. gal).[8]

Production

[edit]Roman amphorae were wheel-thrown terracotta containers. During the production process the body was made first and then left to dry partially.[9] Then coils of clay were added to form the neck, the rim, and the handles.[9] Once the amphora was complete, the maker then treated the interior with resin that would prevent permeation of stored liquids.[10] The reconstruction of these stages of production is based primarily on the study of modern amphora production in some areas of the eastern Mediterranean.[9]

Amphorae often were marked with a variety of stamps, sgraffito, and inscriptions.[11] They provided information on the production, content, and subsequent marketing. A stamp usually was applied to the amphora at a partially dry stage. It indicates the name of the figlina (workshop) and/or the name of the owner of the workshop. Painted stamps, tituli picti, recorded the weight of the container and the contents, and were applied after the amphora was filled. Today, stamps are used to allow historians to track the flow of trade goods and recreate ancient trade networks.[11]

Classification

[edit]The first systematic classification of Roman amphorae types was undertaken by the German scholar Heinrich Dressel. Following the exceptional amphora deposit uncovered in Rome in Castro Pretorio at the end of the 1800s, he collected almost 200 inscriptions from amphorae and included them in the Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum. In his studies of the amphora deposit he was the first to elaborate a classification of types, the so-called "Dressel table",[12] which still is used today for many types.

Subsequent studies on Roman amphorae have produced more detailed classifications, which usually are named after the scholar who studied them. For the neo-Phoenician types see the work by Maña published in 1951,[13] and the revised classification by Van der Werff in 1977–1978.[14] The Gallic amphorae have been studied by Laubenheimer in a study published in 1989,[15] whereas the Cretan amphorae have been analyzed by Marangou-Lerat.[16] Beltràn studied the Spanish types in 1970.[17] Adriatic types have been studied by Lamboglia in 1955.[18] For a general analysis of the Western Mediterranean types see Panella,[19] and Peacock and Williams.[9]

History

[edit]Prehistoric origins

[edit]

Ceramics of shapes and uses falling within the range of amphorae, with or without handles, are of prehistoric heritage across Eurasia, from the Caucasus to China. Amphorae dated to approximately 4800 BC have been found in Banpo, a Neolithic site of the Yangshao culture in China. Amphorae first appeared on the Phoenician coast at approximately 3500 BC.

In the Bronze and Iron Ages amphorae spread around the ancient Mediterranean world, being used by the ancient Greeks and Romans as the principal means for transporting and storing grapes, olive oil, wine, oil, olives, grain, fish, and other agricultural products.[20] They were produced on an industrial scale until approximately the 7th century AD. Wooden and skin containers seem to have supplanted amphorae thereafter.

They influenced Chinese ceramics and other East Asian ceramic cultures, especially as a fancy shape for high-quality decorative ceramics, and continued to be produced there long after they had ceased to be used further west.

Ancient Greece: fancy shapes for painting

[edit]

Besides coarse amphorae used for storage and transport, the vast majority, high-quality painted amphorae were produced in Ancient Greece in significant numbers for a variety of social and ceremonial purposes. Their design differs vastly from the more functional versions; they are typified by wide mouth and a ring base, with a glazed surface and decorated with figures or geometric shapes. They normally have a firm base on which they can stand. Panathenaic amphorae were used as prizes in the Panathenaic Festivals held between the 6th century BC to the 2nd century BC, filled with olive oil from a sacred grove. Surviving examples bear the inscription "I am one of the prizes from Athens", and usually depict the particular event they were awarded for.

Painted amphorae were also used for funerary purposes, often in special types such as the loutrophoros. Especially in earlier periods, outsize vases were used as grave markers, while some amphorae were used as containers for the ashes of the dead. By the Roman period vase-painting had largely died out, and utilitarian amphorae were normally the only type produced.

Greek amphora types

[edit]Various different types of amphorae were popular at different times:

Neck amphora (c. 6th–5th century BC)

[edit]On a neck amphora, the handles are attached to the neck, which is separated from the belly by an angular carination. There are two main types of neck amphorae:

- the Nolan amphora (late 5th century BC), named for its type site, Nola near Naples, and

- the Tyrrhenian amphora.

There are also some rarer special types of neck amphora, distinguished by specific features, for example:

- the Pointed amphora, with a notably pointed toe, sometimes ending in a knob-like protrusion

- the Loutrophoros, used for storing water during ritual ceremonies, such as marriages and funerals.

Belly amphora (c. 640–450 BC)

[edit]In contrast to the neck amphora, a belly amphora does not have a distinguished neck; instead, the belly reaches the mouth in a continuous curve. After the mid-5th century BC, this type was rarely produced. The pelike is a special type of belly amphora, with the belly placed lower, so that the widest point of the vessel is near its bottom. The pelike was introduced around the end of the 6th century BC.

Panathenaic prize amphora

[edit]Another special type is the Panathenaic prize amphora, with black-figure decoration, produced exclusively as prize vessels for the Panathenaia and retaining the black-figure technique for centuries after the introduction of red-figure vase painting. Some examples bear the inscription "ΤΩΝ ΑΘΗΝΗΘΕΝ ΑΘΛΩΝ" meaning "[I am one] of the prizes from [the goddess] Athena". They contained the prize of oil from the sacred olive tree of the goddess Athena for the winners of the athletic contests held to honour the goddess, and were evidently kept thereafter, and perhaps used to store wine, before being buried with the prize-winner. They depicted goddess Athena on one side (as seen on the second image on this page) and the athletic event on the other side, e.g. a scene of wrestling or running contest etc.

-

Panathenaic prize amphora for runners; c. 530 BC; terracotta; height: 62.2 cm (241⁄2 in.); Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

Greek amphora; 2nd half of the 2nd century BC; glass; from Olbia (Roman-era Sardinia); Altes Museum (Berlin)

Ancient Rome

[edit]

By the Roman period utilitarian amphorae were normally the only type produced.

The first type of Roman amphora, Dressel 1, appears in central Italy in the late 2nd century BC.[21] This type had thick walls and a characteristic red fabric. It was very heavy, although also strong. Around the middle of the 1st century BC the so-called Dressel 2-4 starts to become widely used.[22] This type of amphora presented some advantages in being lighter and with thinner walls. It has been calculated that while a ship could accommodate approximately 4500 Dressel 1, it was possible to fit 6000 Dressel 2–4 in the same space.[23] Dressel 2-4 were often produced in the same workshops used for the production of Dressel 1 which quickly ceased to be used.[22]

At the same time in Cuma (southern Italy) the production of the cadii cumani type starts (Dressel 21–22). These containers were mainly used for the transportation of fruit and were used until the middle imperial times. At the same time, in central Italy, the so-called Spello amphorae, small containers, were produced for the transportation of wine. On the Adriatic coast the older types were replaced by the Lamboglia 2 type, a wine amphora commonly produced between the end of the 2nd and the 1st century BC. This type develops later into the Dressel 6A which becomes dominant during Augustan times.[23]

In the Gallic provinces the first examples of Roman amphorae were local imitations of pre-existent types such as Dressel 1, Dressel 2–4, Pascual 1, and Haltern 70. The more typical Gallic production begins within the ceramic ateliers in Marseille during late Augustan times. The type Oberaden 74 was produced to such an extent that it influenced the production of some Italic types.[22] Spanish amphorae became particularly popular thanks to a flourishing production phase in late Republican times. The Hispania Baetica and Hispania Tarraconensis regions (south-western and eastern Spain) were the main production areas between the 2nd and the 1st century BC due to the distribution of land to military veterans and the founding of new colonies. Spanish amphorae were widespread in the Mediterranean area during early imperial times. The most common types were all produced in Baetica and among these there were the Dressel 20, a typical olive oil container, the Dressel 7–13, for garum (fish sauce), and the Haltern 70, for defrutum (fruit sauce). In the Tarraconensis region the Pascual 1 was the most common type, a wine amphora shaped on the Dressel 1, and imitations of Dressel 2–4.

North-African production was based on an ancient tradition which may be traced back to the Phoenician colony of Carthage.[24] Phoenician amphorae had characteristic small handles attached directly onto the upper body. This feature becomes the distinctive mark of late-Republican/early imperial productions, which are then called neo-Phoenician. The types produced in Tripolitania and Northern Tunisia are the Maña C1 and C2, later renamed Van der Werff 1, 2, and 3.[25] In the Aegean area the types from the island of Rhodes were quite popular starting from the 3rd century BC due to local wine production which flourished over a long period. These types developed into the Camulodunum 184, an amphora used for the transportation of Rhodian wine all over the empire. Imitations of the Dressel 2-4 were produced on the island of Cos for the transportation of wine from the 4th century BC until middle imperial times.[26] Cretan containers also were popular for the transportation of wine and can be found around the Mediterranean from Augustan times until the 3rd century AD.[27] During the late empire period, north-African types dominated amphora production. The so-called African I and II types were widely used from the 2nd until the late 4th century AD. Other types from the eastern Mediterranean (Gaza), such as the so-called Late Roman 4, became very popular between the 4th and the 7th century AD, while Italic productions ceased.

The largest known wreck of an amphorae cargo ship, carrying 6,000 pots, was discovered off the coast of Kefalonia, an Ionian island off the coast of Greece.[28]

Modern use

[edit]Some modern winemakers and brewers use amphorae to provide a different palate and taste to their products from those that are available with other aging methods.[29]

See also

[edit]- Ancient Roman pottery

- Ayla-Axum Amphoras

- Carinate

- Demijohn, another large container used historically for wine

- Lionel Casson, scholar of the contents of shipwrecked amphorae

- Maritime archaeology

- Monte Testaccio

- Stirrup jar, a two-handled amphora whose opposing handles connect the aperture to the sides of the vessel

- Tapayan, earthenware and stoneware vessels used for storing and transporting various products in ancient maritime Southeast Asia

- Zafar, Yemen

Citations

[edit]- ^ Twede, D. (2002), "Commercial Amphoras: The Earliest Consumer Packages?", Journal of Macromarketing, 22 (1): 98–108, doi:10.1177/027467022001009, S2CID 154514559, retrieved 19 June 2019

- ^ amphora. Charlton T. Lewis and Charles Short. A Latin Dictionary on Perseus Project.

- ^ ἀμφορεύς. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ^ ἀμφί in Liddell and Scott.

- ^ φορεύς, φέρειν in Liddell and Scott.

- ^ Göransson, Kristian (2007). The transport amphorae from Euesperides: The maritime trade of a Cyrenaican city 400-250 BC. Acta Archaeologica Lundensia, Series in 4o No. 25. Stockholm: Lund. p. 9.

- ^ Ventris, Michael; Chadwick, John (1973). Documents in Mycenaean Greek (2nd ed.). Cambridge: University Press. pp. 324, 328, 494, 532.

- ^ Smith, Sir William; Charles Anthon (1851) A new classical dictionary of Greek and Roman biography, mythology, and geography partly based upon the Dictionary of Greek and Roman biography and mythology New York: Harper & Bros. Tables, pp. 1024–1030

- ^ a b c d Peacock, D. P. S.; Williams, D. F. (1986). Amphorae and the Roman economy: an introductory guide. Longman archaeology series. London; New York: Longman. p. 45.

- ^ Chassouant, Louise; Celant, Alessandra; Delpino, Chiara; Rita, Federico Di; Vieillescazes, Cathy; Mathe, Carole; Magri, Donatella (29 June 2022). "Archaeobotanical and chemical investigations on wine amphorae from San Felice Circeo (Italy) shed light on grape beverages at the Roman time". PLOS ONE. 17 (6) e0267129. Bibcode:2022PLoSO..1767129C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0267129. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 9242518. PMID 35767534.

- ^ a b The Ancient Greek Economy: Markets, Households and City-States. Edward Monroe Harris, David M. Lewis, Mark Woolmer. Cambridge. 2015. ISBN 978-1-139-56553-0. OCLC 941031010.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Dressel 1879, Di un grande deposito di anfore rinvenuto nel nuovo quartiere del Castro Pretorio, in BullCom, VII, 36–112, 143–196.

- ^ Maña, Sobre tipologia de ánforas pùnicas, in VI Congreso Arqueologico del Sudeste Español, Alcoy, 1950, Cartagena, 1951, 203–210

- ^ Amphores de tradition punique à Uzita, in BaBesch 52-53, 171-200

- ^ Laubenheimer, Les amphores gauloises sous l'empire: recherches nouvelles sur leur production et chronologie, in Amphores romaines et histoire économiqué: dis ans de recherche. Actes du Colloque de Sienne (22-24 mai 1986), Rome, 105-138

- ^ Marangou-Lerat, Le vin et les amphores de Crète de l'epoque classique à l'epoque impériale, in Etudes Cretoises, 30, Paris, 1995

- ^ Beltràn, Las anforas Romanas en Espana, Zaragoza

- ^ "Sulla cronologia delle anfore romane di età repubblicana" in Rivista Studi Liguri 21, 252–60

- ^ Panella 2001, pp. 177–275:

Le anfore di età imperiale del Mediterraneo occidentale

, in Céramiques hellénistiques et romaines III - ^ Adkins, L.; Adkins, R. A. (1994). Handbook to life in Ancient Rome. New York, N.Y.: Facts on File. p. 196. ISBN 978-0-8160-2755-2.

- ^ Panella 2001, p. 177.

- ^ a b c Panella 2001, p. 194.

- ^ a b Bruno 2005, p. 369.

- ^ Panella 2001, p. 207.

- ^ Van der Werff 1977-78.

- ^ Bruno 2005, p. 374.

- ^ Bruno 2005, p. 375.

- ^ Buckley, Julia (16 December 2019). "Biggest ever Roman shipwreck found in the eastern Med". CNN Travel. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- ^ "Back to the future". Cantillon.be/br/. Brasserie Cantillon. Archived from the original on 6 November 2014. Retrieved 6 November 2014.

General references

[edit]- Bruno, Brunella (2005), "Le anfore da trasporto", in Gandolfi, Daniela (ed.), La ceramica e i materiali di Età Romana. Classi, produzioni, commerci e consumi, Bordighera: Istituto Internazionale di Studi Liguri.

- Panella, Clementina (2001), "Le anfore di età imperiale del Mediterraneo occidentale", in Lévêque, Pierre; Morel, Jean Paul Maurice (eds.), Céramiques hellénistiques et romaines III (in French), Paris: Belles Lettres, pp. 177–275.

External links

[edit]- Amphorae ex Hispania

- The AMPHORAS project Archived 30 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Bulletin amphorologique

- Roman Amphorae: a digital resource from the University of Southampton

- Roman Amphoras in Britain in Internet Archaeology doi:10.11141/ia.1.6