Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

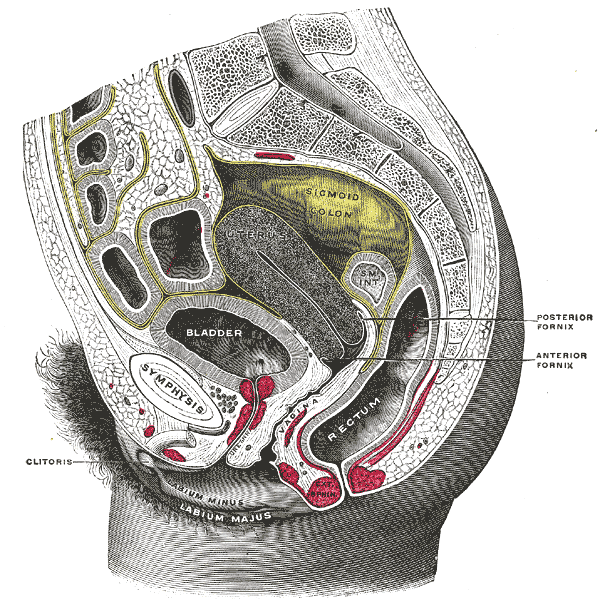

Vaginal fornix

View on Wikipedia| Vaginal fornix | |

|---|---|

| |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | fornix vaginae |

| TA98 | A09.1.04.002 |

| TA2 | 3524 |

| FMA | 19985 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The fornices of the vagina (sg.: fornix of the vagina or fornix vaginae) are the superior portions of the vagina, extending into the recesses created by the vaginal portion of cervix. There is an anterior fornix and a posterior fornix. The word fornix is Latin for 'arch'.

Sexuality

[edit]During sexual intercourse in the missionary position, the tip of the penis may reach the anterior fornix, while in the rear-entry position it may reach the posterior fornix.[1]

The anterior fornix is also called the a-spot, an analogue to the g-spot (Gräfenberg spot), which is closer to the vaginal opening, and also on the anterior side of the vagina.[2]

References

[edit]![]() This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 1264 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 1264 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- ^ Faix, A.; Lapray, J. F.; Callede, O.; Maubon, A.; Lanfrey, K. (15 February 2002). "Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of Sexual Intercourse: Second Experience in Missionary Position and Initial Experience in Posterior Position". Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. 28 (sup1): 63–76. doi:10.1080/00926230252851203. PMID 11898711. S2CID 16407035.

- ^ "A-Spot - Ann Summer". www.annsummers.com. Retrieved 20 August 2024.

External links

[edit]- MedEd at Loyola Grossanatomy/dissector/practical/pelvis/pelvis14.html

- Anatomy photo:43:10-0201 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center – "The Female Pelvis: The Vagina"

- Histology image: 19401loa – Histology Learning System at Boston University – "Female Reproductive System: cervix, longitudinal"

- figures/chapter_35/35-2.HTM: Basic Human Anatomy at Dartmouth Medical School