Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

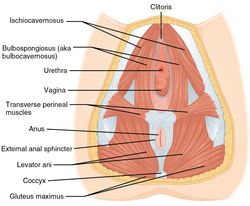

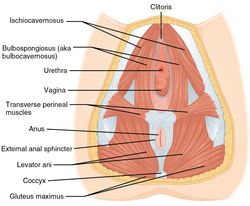

Vaginal support structures

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2018) |

The vaginal support structures are those muscles, bones, ligaments, tendons, membranes and fascia, of the pelvic floor that maintain the position of the vagina within the pelvic cavity and allow the normal functioning of the vagina and other reproductive structures in the female. Defects or injuries to these support structures in the pelvic floor leads to pelvic organ prolapse. Anatomical and congenital variations of vaginal support structures can predispose a woman to further dysfunction and prolapse later in life.[1] The urethra is part of the anterior wall of the vagina and damage to the support structures there can lead to incontinence and urinary retention.[2]

Pelvic bones

[edit]The support for the vagina is provided by muscles, membranes, tendons and ligaments. These structures are attached to the hip bones. These bones are the pubis, ilium and ischium. The interior surface of these pelvic bones and their projections and contours are used as attachment sites for the fascia, muscles, tendons and ligaments that support the vagina. These bones are then fuse and attach to the sacrum behind the vagina and anteriorly at the pubic symphysis.[3] Supporting ligaments include the sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligaments. The sacrospinous ligament is unusual in that it is thin and triangular.[3][4]

Pelvic diaphragm

[edit]The muscular pelvic diaphragm is composed of the bilateral levator ani and coccygeus muscles and these attach to the inner pelvic surface. The iliococcygeus and pubococcygeus make up the levator ani muscle. The muscles pass behind the rectum. The levator ani surrounds the opening which the urethra, rectum and vagina pass. The pubococcygeus muscle is subdivided into the pubourethralis, pubovaginal muscle and the puborectalis muscle. The names describe the attachments of the muscles to the urethra, vagina, anus, and rectum. The names are also called the pubourethralis, pubovaginalis, puboanalis, and puborectalis muscles and sometimes the pubovisceralis since it attaches to the viscera.[3]

Urogenital diaphragm (perineal membrane)

[edit]The urogenital diaphragm, or perineal membrane, is present over the anterior pelvic outlet below the pelvic diaphragm.[5] The exact structure description is controversial. Despite the controversy, MRI imaging studies support the existence of the structure.[3][6]

Superficial and inferior muscles of the perineum (urogenital diaphragm):

The perineum attaches across the gap between the inferior pubic rami bilaterally and the perineal body. This grouping of muscles constricts to close the urogenital openings. The perineum supports and functions as a sphincter at the opening of the vagina. Other structures exist below the perineum that support the anus.[3][6]

Perineal body

[edit]

The perineal body is a pyramidal structure of muscle and connective tissue and part of it is located between the anus and vagina. It is a tendon that is formed at the point where the bulbospongiosus muscle, superficial transverse perineal muscle,[7] and external anal sphincter muscle converge to form this major supportive structure of the pelvis and vagina.[8][9][10] Below this, muscles and their fascia converge and become part of the perineal body. The lower vagina is attached to the perineal body by attachments from the pubococcygeus, perineal muscles, and the anal sphincter. The perineal body is made up of smooth muscle, elastic connective tissue fibers, and nerve endings. Above the perineal body are the vagina and the uterus. Damage and resulting weakness of the perineal body changes the length of the vagina and predisposes it to rectocele and enterocele.[3][6]

Endopelvic fascia and connective tissue

[edit]

The vagina is attached to the pelvic walls by endopelvic fascia. The peritoneum is the external layer of skin that covers the fascia. This tissue provides additional support to the pelvic floor. The endopelvic fascia is one continuous sheet of tissue and varies in thickness. It permits some shifting of the pelvic structures. The fascia contains elastic collagen fibers in a 'mesh-like' structure. The fascia also contains fibroblasts, smooth muscle, and vascular vessels. The cardinal ligament supports the apex of the vagina and derives some of its strength from vascular tissue. The endopelvic fascia attaches to the lateral pelvic wall via the arcus tendineus.[3]

Anterior vaginal support

[edit]Not all agree to the amount of supportive tissue or fascia exists in the anterior vaginal wall. The major point of contention is whether the vaginal fascial layer exists. Some texts do not describe a fascial layer. Other sources state that the fascia is present under the urethra which is embedded in the anterior vaginal wall.[3] Despite disagreement, the urethra is embedded in the anterior vaginal wall.[3]

Lateral and mid support structures

[edit]The midsection of the vagina is supported by its lateral attachments to the arcus tendineus. Some describe the pubocervical fascia as extending from the pubic symphysis to the anterior vaginal wall and cervix. Anatomists do not agree on its existence.[3][11]

Complications

[edit]Vaginal support structures can be damaged or weakened during childbirth or pelvic surgery. Other conditions that repeatedly strain or increase pressure in the pelvic area can also compromise support. Examples are:[12]

- chronic constipation

- chronic or violent coughing

- heavy lifting

- being overweight or obese[2]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]![]() This article incorporates text in the public domain from the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- ^ Craft, T. M.; Parr, M. J. A.; Nolan, Jerry P. (2004-11-10). Key Topics in Critical Care, Second Edition. CRC Press. p. 1068. ISBN 9781841843582.

- ^ a b "Cystocele (Prolapsed Bladder) | NIDDK". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Retrieved 2018-02-03.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Herschorn, Sender (2004). "Female Pelvic Floor Anatomy: The Pelvic Floor, Supporting Structures, and Pelvic Organs". Reviews in Urology. 6 (Suppl 5): S2–S10. ISSN 1523-6161. PMC 1472875. PMID 16985905.

- ^ "Human Anatomy". ect.downstate.edu. Archived from the original on 2012-07-17. Retrieved 2018-02-05.

- ^ TA A09.5.03.002

- ^ a b c Snell, Richard S. (2004). Clinical Anatomy: An Illustrated Review with Questions and Explanations. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 99. ISBN 9780781743167.

- ^ Also known as transversus perinaei superficialis.

- ^ Sarton, Julie (2010). "Assessment of the Pelvic Floor Muscles in Women with Sexual Pain". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 7 (11): 3526–3529. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02059.x. PMID 21064249.

- ^ "Superficial transverse perineal muscle". IMAIOS. Retrieved 2018-02-03.

- ^ "Human Anatomy, The Female Perineum, Muscles of the Superficial Perineal Pouch". act.downstate.edu. SUNY Downstate Medical Center. Archived from the original on 2019-07-31. Retrieved 2018-02-03.

- ^ "Arcus tendineus fasciae pelvis". TheFreeDictionary.com. Retrieved 2018-02-03.

- ^ "Vaginal and cervical trauma". stratog.rcog.org.uk. Archived from the original on 2018-02-10. Retrieved 2018-02-10.