Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cardinal ligament

View on Wikipedia| Cardinal ligament | |

|---|---|

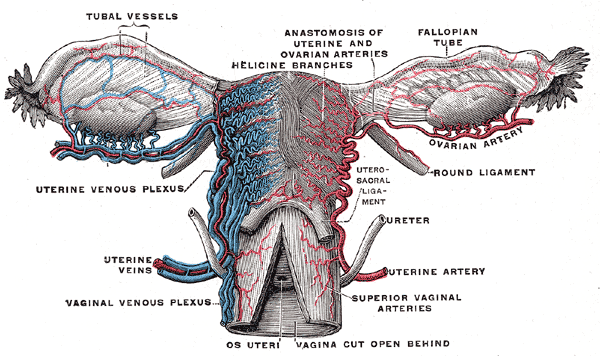

Vessels of the uterus and its appendages, rear view. (Cardinal ligament not visible, but location can be inferred from position of uterine artery and uterine vein.) | |

Uterus and right broad ligament, seen from behind. (Cardinal ligament not labeled, but broad ligament visible at center.) | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | ligamentum cardinale, ligamentum transversum cervicis, ligamentum transversalis colli |

| TA98 | A09.1.03.031 A09.1.03.022 |

| TA2 | 3839 |

| FMA | 77064 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The cardinal ligament (also transverse cervical ligament, lateral cervical ligament,[1] or Mackenrodt's ligament[2][1]) is a major ligament of the uterus formed as a thickening of connective tissue of the base of the broad ligament of the uterus. It extends laterally (on either side) from the cervix and vaginal fornix to attach onto the lateral wall of the pelvis. The female ureter, uterine artery, and inferior hypogastric (nervous) plexus course within the cardinal ligament. The cardinal ligament supports the uterus.[1]

Structure

[edit]The cardinal ligament is a paired structure on the lateral side of the uterus. It originates from the lateral part of the cervix.[3]

Attachments

[edit]It attaches the cervix to the lateral pelvic wall by its attachment to the obturator fascia of the obturator internus muscle.[4] It attaches to the uterosacral ligament.[3]

Relations

[edit]It is continuous externally with the fibrous tissue surrounding the pelvic blood vessels.[4]

Function

[edit]The cardinal ligament supports the uterus, providing lateral stability to the cervix.[1]

Clinical significance

[edit]The cardinal ligament may be affected in hysterectomy.[5][6] Due to its proximity to the ureters, it can get damaged during ligation of the ligament. It is routinely cut during some uterine operations, although this can have side effects.[3]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]![]() This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 1261 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 1261 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- ^ a b c d Sinnatamby, Chummy (2011). Last's Anatomy (12th ed.). p. 304. ISBN 978-0-7295-3752-0.

- ^ Netter, Frank H. (2003). Atlas of Human Anatomy, Professional Edition. Philadelphia: Saunders. p. 370. ISBN 1-4160-3699-7.

- ^ a b c Ito, E.; Saito, T. (December 2004). "Nerve-preserving techniques for radical hysterectomy". European Journal of Surgical Oncology. 30 (10): 1137–1140. doi:10.1016/j.ejso.2004.06.004. ISSN 0748-7983. PMID 15522564.

- ^ a b Kyung Won, PhD. Chung (2005). Gross Anatomy (Board Review). Hagerstown, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 274. ISBN 0-7817-5309-0.

- ^ Kato T, Murakami G, Yabuki Y (2002). "Does the cardinal ligament of the uterus contain a nerve that should be preserved in radical hysterectomy?". Anat Sci Int. 77 (3): 161–8. doi:10.1046/j.0022-7722.2002.00023.x. PMID 12422408. S2CID 43367709.

- ^ Kato T, Murakami G, Yabuki Y (2003). "A new perspective on nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy: nerve topography and over-preservation of the cardinal ligament". Jpn J Clin Oncol. 33 (11): 589–91. doi:10.1093/jjco/hyg107. PMID 14711985.

External links

[edit]- figures/chapter_35/35-5.HTM: Basic Human Anatomy at Dartmouth Medical School

- part_6/chapter_35.html: Basic Human Anatomy at Dartmouth Medical School