Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

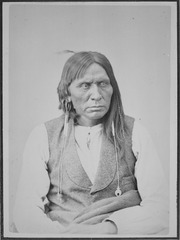

Waco people

View on WikipediaThe Waco (also spelled Huaco[2] and Hueco[3]) of the Wichita people are a Southern Plains Native American tribe that inhabited northeastern Texas.[4] Today, they are enrolled members of the federally recognized Wichita and Affiliated Tribes, headquartered in Anadarko, Oklahoma (seat of Caddo County).

Key Information

History

[edit]The Waco were a division of the Wichita people, called Iscani or Yscani in the early European reports, kinsmen to the Tawakoni people. The present-day Waco, Texas, is located on the site of their principal village, that stood at least until 1820.[5] French explorer Jean-Baptiste Bénard de la Harpe travelled through the region in 1719, and the people he called the Honecha or Houecha could be the Waco.[6] They are most likely the Quainco on Guillaume de L'Isle's 1718 map, Carte de la Louisiane et du Cours du Mississipi.[7][8]

The Waco village on the Brazos River was flanked by two Tawakoni villages: El Quiscat and the Flechazos. In 1824, Stephen F. Austin wrote that the Waco village was 40 acres large, with 33 grass houses and about 100 men. They grew 200 acres of corn in fields enclosed by brush fences. As late as 1829, the village was protected by defensive earthworks.[6] In 1837, the Texas Rangers planned to establish a fort at Waco village, but abandoned the idea after several weeks. In 1844, a trading post was established 8 miles south of the village.[9] The anthropologist Jean-Louis Berlandier recorded 60 Waco houses in 1830.[10]

The tribe had a second, smaller village located on the Guadalupe River.[10]

In 1835, 1846, and 1872, the tribe signed treaties with the United States and the Wichita. The 1872 treaty established a reservation for them in Indian Territory, to which they were removed. In 1902, under the Dawes Allotment Act, the reservation lands were broken into individual allotments, and the Wacos became citizens of the United States.[6] Today, they are part of the Wichita and Affiliated Tribes.

Culture

[edit]The tribe lived in beehive-shaped houses, with pole supports, typically covered with rushes, but sometimes buffalo hides. The houses stood 20 to 25 feet tall. Besides corn, Wacos also grew beans, melons, peach trees, and pumpkins.[9]

Waco descendants and other citizens of the Wichita and Affiliated Tribes are partnering with cultural organizations in Waco, Texas, educate the public about Waco history and create new opportunities for the city to work with Wichita people.[11]

Language

[edit]The Waco people spoke a dialect called Waco, which is a branch of Wichita (one of the Caddoan languages). The dialect is extinct.

Namesakes

[edit]The city of Waco, Texas, is named for the tribe,[12][9] as probably is Hueco Springs (Waco Springs) near New Braunfels, Texas.[10][13]

References

[edit]- ^ Gately, Paul (8 July 2018). "Native Americans chose Waco for water and abundance, like others". 10 KWTX. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- ^ Straley, Wilson (1909). The Archaeological Bulletin. p. 132.

[...] the city of Waco, Texas, the former home of the Huaco (Waco) Indians.

- ^ Henry, Joseph; Baird, Spencer Fullerton (1856). Reports of explorations and surveys. A.O.P. Nicholson. p. 27.

the Huéco tribe [...] Hueco Indians

- ^ Sturtevant 6

- ^ "Waco Springs, Site of the Waco Indian Village - Waco ~ Marker Number: 5692". Texas Historic Sites Atlas. Texas Historical Commission. 1936.

- ^ a b c Waco Indian History. Access Genealogy. (retrieved 26 Oct 2010)

- ^ Ricky, Donald (1998). Encyclopedia of Texas Indians. North American Book Dist. p. 353. ISBN 978-0-403-09774-6.

- ^ de L'Isle's map.

- ^ a b c Waco Convention & Visitors Bureau, "Waco History." Archived 2015-01-06 at the Wayback Machine (retrieved 26 Oct 2010)

- ^ a b c Moore, R. Edward. "The Waco Indians or Hueco Indians." Texas Indians. (retrieved 26 Oct 2010)

- ^ Hoover, Carl (3 November 2023). "Wichitas hope Waco visit builds beneficial relationships". Waco Tribune-Herald. Retrieved 4 November 2023.

- ^ Mencken, H.L. (1948). American Language Supplement 2. Knopf Doubleday (1990 reprint). p. 1050. ISBN 978-0-307-81344-2.

Many other non-English place-names have been subjected to the same barbarization. [...] Waco in Texas was the Spanish Hueco.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Greene, Daniel P. (2010). "Waco Springs, TX". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association.

There are differing explanations for the name of the site: that it was named for the Indian tribe; that the name comes from Spanish hueco (empty) and was chosen because the springs occasionally run dry.

Further reading

[edit]- Sturtevant, William C., general editor and Raymond D. Fogelson, volume editor. Handbook of North American Indians: Southeast. Volume 14. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution, 2004. ISBN 0-16-072300-0.

External links

[edit]Waco people

View on GrokipediaOrigins and Pre-Colonial History

Linguistic and Cultural Affiliations

The Waco people spoke a dialect of the Wichita language, classified within the Caddoan language family, which encompasses several Northern Caddoan languages historically spoken across the southern Great Plains.[4][3] This dialect, closely related to other Wichita variants, is now extinct, with no fluent speakers remaining due to historical disruptions including disease, warfare, and forced relocation.[4][5] Culturally, the Waco were closely affiliated with the Wichita confederacy, forming part of a loose alliance of related Caddoan-speaking bands that included the Tawakoni, Keechi, and Taovayas, sharing subsistence practices, matrilineal kinship systems, and semi-sedentary village life centered on agriculture and hunting.[3][6] While maintaining a distinct tribal identity and territory in central Texas, they participated in intertribal trade networks and defensive coalitions against common enemies such as Apache and Comanche groups, reflecting a broader Southern Plains cultural complex adapted to riverine environments.[3][5] Today, Waco descendants are enrolled in the Wichita and Affiliated Tribes in Oklahoma, preserving elements of this shared heritage through federal recognition and cultural revitalization efforts.[7]Early Migrations and Settlement Patterns

The Waco, known as Wi-iko in their language, formed one of the southern bands within the Wichita confederacy, a Caddoan-speaking group whose ancestors participated in the Plains Village tradition beginning approximately 800 CE. This prehistoric cultural complex, evidenced across southern Kansas, northern Oklahoma, and northern Texas, featured semi-permanent villages with circular, thatched-grass houses constructed near river floodplains for agricultural productivity. Proto-Wichita peoples cultivated maize, beans, and squash while supplementing their diet through hunting large game such as bison and deer, establishing settlement patterns oriented toward fertile river valleys that supported year-round habitation rather than nomadic pursuits.[8][3] Between the 16th and 18th centuries, Wichita confederacy bands, including the Waco, migrated southward from core territories along the Arkansas River in present-day Kansas through Oklahoma and into Texas, influenced by factors such as intertribal warfare, Osage incursions from the north, and the acquisition of horses from Spanish sources that facilitated expanded mobility and buffalo hunting. The Waco band, distinguishing itself as more southern-oriented, reached central Texas by the early 1700s, where they concentrated settlements along the middle Brazos River to leverage its reliable water and alluvial soils for intensified farming. These migrations reflected adaptive strategies within the confederacy, with southern groups like the Waco and Tawakoni prioritizing defensible village clusters over the dispersed hunting camps of northern kin.[9][5][10] Waco settlement patterns emphasized clustered villages of 100 to 300 individuals, often fortified with palisades against raids, situated at confluences or bends in rivers like the Brazos for defensive advantages and access to diverse resources. Horticulture dominated, with fields irrigated via simple ditches and crop storage in elevated granaries, while seasonal forays extended hunting ranges onto the plains; this riverine focus persisted into the historic period, as evidenced by French explorer Athanase de Mézières' 1772 observation of two substantial Waco villages during his Brazos River expedition. Such patterns underscored the Waco's role as agrarian intermediaries between woodland farming traditions and plains nomadic economies.[1][11][3]18th and 19th Century Developments

Establishment in Central Texas

The Waco, a Caddoan-speaking band of the Wichita people, migrated into Central Texas during the mid-eighteenth century, relocating southward from areas near the Red River amid pressures from northern tribes.[3] They established semi-permanent villages along the middle Brazos River, in the vicinity of present-day Waco, Texas, transitioning from more nomadic patterns to agrarian settlements supported by riverine resources.[1] These communities featured dome-shaped grass lodges housing extended families and reflected a mixed economy of horticulture and seasonal hunting.[1] The first European documentation of Waco presence in the region dates to 1772, when French explorer Athanase de Mézières recorded two villages during his upstream expedition along the Brazos, noting their organized layout and agricultural fields.[1] Residents cultivated staple crops including corn, lima beans, pumpkins, and melons, while pursuing buffalo and deer hunts in autumn using temporary shelters.[1] This settlement phase, spanning the late 1700s, enabled trade networks with neighboring groups and early Spanish outposts, though it remained vulnerable to inter-tribal raids that influenced subsequent relocations upstream.[3]Interactions with European Settlers and Neighboring Tribes

The Waco, a subtribe of the Wichita, maintained primarily trade-based interactions with early European explorers and traders in the late 18th century. In 1772, French trader Athanase de Mézières, operating under Spanish authority, documented two Waco villages along the Brazos River during an expedition, noting their agricultural settlements but recording no immediate hostilities.[12][1] These encounters involved exchanges of corn, hides, and captives for European goods such as metal tools and firearms, though the Waco resisted Spanish missionary efforts aimed at relocation to missions further south.[13] Relations with neighboring tribes were marked by both alliances and conflicts, shaped by competition for resources in central Texas. The Waco allied with fellow Caddoan groups like the Tawakoni and other Wichita bands for mutual defense and trade, sharing agricultural surpluses and village networks against nomadic raiders.[14] However, they faced frequent raids from Comanche and Apache groups, who targeted Waco cornfields and horses, leading to retaliatory skirmishes that disrupted Waco settlements by the early 19th century.[15] A notable intra-regional conflict occurred in 1837 at Waco Spring, where Waco warriors clashed with Tonkawa hunters over hunting grounds, resulting in significant casualties on both sides.[16] Around 1830, Cherokee migrants displaced the Waco from their primary village near the future site of Waco, Texas, forcing northward shifts.[17] As Anglo-American settlement intensified after Texas independence in 1836, interactions with European-descended settlers shifted toward formalized treaties amid rising tensions. In 1824, Stephen F. Austin dispatched a delegation that negotiated a peace agreement with Waco leaders, aiming to secure safe passage for colonists, though enforcement was inconsistent.[1] The Republic of Texas pursued further diplomacy, including the 1843 council at Bird's Fort involving Waco, Caddo, and other tribes, and the 1844 Treaty of Tehuacana Creek, which promised land boundaries and trade but collapsed due to mutual raid accusations.[18][19] Conflicts escalated with settler attacks, such as Henry Stevenson Brown's 1825 raid that destroyed a Waco band encampment, and Waco counter-raids on frontier farms, prompting the establishment of Texas Ranger outposts like Fort Fisher in the 1840s to curb depredations.[20][17] Subsequent U.S. treaties in 1846 and 1850, signed with Waco alongside Comanche, Tawakoni, and others, reiterated peace pledges but failed to prevent displacement as settler expansion eroded Waco territory.[21][13]Conflicts, Decline, and Population Losses

The Waco faced initial inter-tribal conflicts in the late 1820s, particularly with Cherokee bands. Historical accounts indicate that hostilities began in 1828 when a group of Waco stole horses from a Cherokee settlement, prompting retaliatory raids by Cherokee warriors that devastated the Waco village around 1829–1830.[22][1] These attacks forced the Waco to abandon their primary settlement on the Brazos River, marking the beginning of their displacement northward along the river.[23] As Anglo-American settlers encroached into central Texas during the 1830s and 1840s, tensions escalated into direct conflicts. The Waco, responding to territorial losses, conducted raids on settler communities, which in turn provoked retaliatory expeditions by Texas Rangers and militia.[24] These skirmishes were part of the broader Texas–Indian wars, contributing to ongoing violence and further erosion of Waco autonomy.[17] By the mid-1830s, the original village site was fully abandoned, with survivors relocating upstream amid persistent threats from both settlers and rival tribes like the Comanche.[1][25] Population losses were severe, driven by warfare, disease, and displacement. In 1824, the Waco village supported an estimated 500 to 600 residents, but by the mid-1830s, these numbers had plummeted due to the cumulative impacts of raids and epidemics associated with European contact.[23] Hostilities with Texas authorities culminated in the tribe's forced removal to a reservation in Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) in 1859, alongside other Wichita bands, effectively ending their presence in Texas.[3] This relocation, combined with earlier losses, reduced the Waco to a small remnant group absorbed into the broader Wichita confederacy, with their distinct identity diminishing thereafter.[3]Society and Traditional Culture

Subsistence Economy and Agriculture

The Waco, a band of the Wichita confederacy, practiced a mixed subsistence economy reliant on semi-sedentary agriculture in fertile riverine villages, combined with seasonal hunting and gathering to ensure food security and material needs. Primary crops included maize (corn), lima beans, pumpkins, melons, and squash, cultivated by women using hoes fashioned from animal shoulder blades or mussel shells in bottomlands along the Brazos River.[1][5] These staples formed the dietary foundation, with surplus dried or stored in earthen pits for winter consumption, enabling village stability amid variable rainfall.[26] Hunting expeditions intensified post-harvest in autumn, when families decamped to the open plains in portable tipis to pursue bison herds using bows, arrows, and communal drives, yielding meat for pemmican, hides for clothing and shelter, and bones for tools.[1] Deer, elk, pronghorn, rabbits, and smaller game supplemented protein sources year-round, often trapped or snared near settlements, while gathered wild plants like nuts, roots, and berries diversified nutrition during lean periods.[8] This mobility balanced agricultural sedentism, with horses—acquired via trade by the mid-18th century—enhancing hunt efficiency and transport of yields.[3] Trade networks with French merchants and neighboring tribes exchanged agricultural produce, hides, and crafted items like pottery for metal tools and textiles, gradually integrating market elements into traditional foraging without fully supplanting self-sufficiency.[3] Environmental pressures, including droughts and intertribal raids, periodically strained resources, prompting adaptive shifts toward intensified bison reliance by the early 19th century.[27]Social Structure and Governance

The Waco people organized their society into autonomous villages, each comprising extended family groups that formed the core social units. Descent was traced matrilineally, following patterns common among Wichita-affiliated bands, where kinship ties emphasized maternal lineages and clan affiliations influenced marriage rules and inheritance.[10] Villages typically housed 100 to 300 individuals, with social roles divided by gender: men handled hunting, warfare, and trade, while women managed agriculture, pottery, and child-rearing, reflecting a complementary division of labor in their semi-sedentary agrarian lifestyle.[28] Governance centered on village headmen, often hereditary leaders selected for wisdom and diplomacy, who mediated disputes, organized communal hunts, and represented the group in intertribal councils.[3] These headmen held authority recognized by neighboring tribes and later by U.S. reservation agents, but power was not absolute; decisions on war, migration, or alliances required consensus from a council of elders and prominent warriors, underscoring a decentralized structure within the broader Wichita confederacy.[28] Lacking a paramount chief, the Waco emphasized village autonomy, which facilitated adaptability to environmental pressures but limited unified responses to external threats like Comanche raids in the early 19th century.[3]Material Culture and Daily Life

The Waco, a subtribe of the Tawakoni within the broader Wichita linguistic and cultural group, inhabited semi-permanent villages along the Brazos River in central Texas, where they built dome-shaped dwellings framed with poles and thatched with grasses and willow branches. These grass houses typically included a central fire pit for cooking and warmth, with interiors furnished by buffalo robes and deerskins used as bedding and floor coverings. Villages encompassed fenced agricultural fields spanning around 200 acres, supporting a sedentary lifestyle during the growing season.[1][29] Daily routines centered on agriculture, with men and women collaboratively planting, tending, and harvesting crops such as corn, beans, squash, melons, pumpkins, and lima beans using tools fashioned from stone, wood, and bone, including hoes and digging sticks. Women processed foodstuffs, prepared meals over open fires, and gathered wild plants for dietary supplements, medicines, and rituals, while men focused on hunting deer and seasonal buffalo migrations on the plains following the fall harvest. During these expeditions, families relocated temporarily, relying on portable shelters and preserved foods from village stores.[30][8][1] Traditional attire reflected available hides and the region's climate: men wore buffalo-skin breechcloths with bare chests and moccasins of buffalo or deerskin, while women donned short deerskin skirts, often leaving upper bodies uncovered and adorned with tattoos for aesthetic and possibly protective purposes. Hunting implements included bows, arrows tipped with stone points, and spears, supplemented by bone awls and knives for skinning and crafting. Pottery and woven baskets served for storage and cooking, though specific Waco variants remain sparsely documented in archaeological records due to the tribe's dispersal by the mid-19th century.[29][8]Language

The Waco people spoke a Northern Caddoan language closely related to that of the Wichita, with which they were culturally and linguistically affiliated as a band or subtribe.[3][4] This language belonged to the broader Caddoan family, which includes branches such as Wichita, Kitsai, Pawnee, and Arikara, originating from ancient Plains linguistic stocks.[5][6] Documentation of the Waco dialect remains extremely limited, as European contact records focused more on Wichita variants, and no comprehensive grammars or dictionaries were compiled before its decline.[4] It shared phonetic and grammatical features with Wichita, such as complex verb structures and tonal elements typical of Caddoan tongues, but distinct lexical items may have reflected local adaptations in Central Texas.[6] The language became extinct by the late 19th century, coinciding with the Waco's assimilation into broader Wichita groups and forced relocation, leaving no known fluent speakers today.[4] Revitalization efforts within the Wichita and Affiliated Tribes focus primarily on Wichita proper, with archival materials offering indirect insights into Waco speech patterns through bilingual trader accounts and early ethnographies.[3]Displacement and Modern Descendants

Forced Removal to Indian Territory

In the mid-19th century, escalating conflicts between the Waco and other affiliated tribes—such as the Wichita, Tawakoni, and Caddo—and Anglo-American settlers in Texas intensified pressures for relocation.[3] The U.S. government established the Brazos Indian Reservation in 1854 near present-day Fort Belknap, Texas, to consolidate these groups and mitigate raids attributed to them, but settler complaints persisted amid reports of attacks on frontier communities.[31] By 1859, following a petition from hundreds of white settlers citing ongoing raids, federal authorities decided to dissolve the reservation and forcibly remove the tribes to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma).[31][32] The removal occurred in 1859, with federal troops escorting the Waco, along with Tawakoni (approximately 258 individuals), Wichita, Caddo, Delaware, and others, from the Brazos Reservation to the Leased District in western Indian Territory, a temporary area leased from the Comanche and Kiowa for such purposes.[3][33] This relocation was driven by settler demands for land security and federal policy to clear Texas of remaining Indigenous populations, rather than a specific treaty mandating the move; earlier agreements, such as those in 1835 and 1846 with the Wichita (encompassing Waco remnants), had already begun eroding territorial claims.[5] The Waco population had dwindled severely by this point due to prior epidemics and warfare, leaving only small bands to undertake the journey northward.[34] Upon arrival, the groups were initially placed under the Wichita Agency in the Leased District, but the Civil War disrupted stability; Confederate forces pressured the tribes to relocate temporarily to Kansas in 1863, where they remained until 1867 before returning to reestablish villages in Indian Territory.[3] A subsequent treaty in 1872 formalized a permanent reservation for the Wichita and Affiliated Tribes, including the Waco, in what became Caddo and Grady Counties, Oklahoma, marking the end of their forced displacement from Texas homelands.[35] This process exemplified broader U.S. removal policies post-Texas annexation, prioritizing settler expansion over Indigenous land rights, with the Waco integrating into the affiliated tribal structure thereafter.[32]Current Tribal Affiliation and Population

The descendants of the Waco people are enrolled in the federally recognized Wichita and Affiliated Tribes, which encompasses the Wichita, Keechi, Waco, and Tawakonie divisions and is headquartered in Anadarko, Oklahoma.[36] This affiliation stems from historical mergers following forced removals to Indian Territory in the 19th century, where the Waco integrated with related Caddoan-speaking groups.[10] There is no separate federally recognized Waco tribe today; Waco identity persists within this unified tribal structure.[37] As of October 17, 2025, the Wichita and Affiliated Tribes reports 3,879 enrolled members, including descendants of the Waco.[38] Specific enrollment figures for Waco descendants alone are not separately tracked or publicly detailed by the tribe, reflecting their incorporation into the broader affiliated population. The tribe's service area primarily covers Caddo County in Oklahoma, with members residing both on and off the reservation.[39]Cultural Preservation and Revitalization

The Wichita and Affiliated Tribes, which include the Waco as one of its constituent groups, maintain a Department of Preservation dedicated to safeguarding historic, archaeological, and traditional cultural properties on tribal lands, including programs for language and cultural services.[40] This encompasses efforts to document and revive the Wichita language, a Caddoan tongue spoken historically by the Waco and related peoples, amid challenges from historical suppression in boarding schools where children were prohibited from using their native languages.[41] The tribe established an archive specifically to organize existing language materials as a foundation for revitalization, recognizing documentation as essential to countering near-extinction after the death of the last fluent heritage speaker in the mid-2010s.[42] Cultural revitalization initiatives include annual events such as the Wichita Annual Dance, which serves to transmit traditions and reinforce community identity among the enrolled membership of approximately 2,150 as of 2002, with many residing near Anadarko, Oklahoma.[10][30] The tribe has pursued land reclamation to anchor these efforts, notably reacquiring the 230-acre Serpent Site in May 2024—a 600-year-old effigy mound within ancestral homelands—to protect archaeological features tied to prehistoric Wichita and Affiliated Tribes' history.[43] Community-based programs, including a developing museum and historical center near Anadarko, aim to educate members and the public on material culture, such as grass house construction, through partnerships like the October 2025 collaboration with Baylor University's Mayborn Museum to replicate traditional Waco dwellings using Wichita artisans.[44][45][42] Broader outreach emphasizes education and engagement, with tribal members advocating for awareness of Waco heritage in regional contexts, such as deepened ties with institutions in Waco, Texas—named after the tribe—to promote language, history, and future-oriented cultural continuity.[46] Federal grants support these activities, including $105,899 allocated for language preservation, NAGPRA compliance, and tribal historic preservation under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act.[39] These initiatives reflect a strategic focus on sovereignty through documentation and community building, countering twentieth-century disruptions while adapting traditions to contemporary tribal governance.[47]Legacy and Impact

Archaeological and Historical Sites

The principal village of the Waco people, a Caddoan-speaking band related to the Wichita, was situated along the Brazos River in present-day Waco, Texas, where the tribe resided in beehive-shaped thatched dwellings until their displacement around 1837 by Comanche incursions.[1] [48] A Texas Historical Commission marker at the site, erected in 1936 and located at the Helen Marie Taylor Museum of Waco History, notes the Waco's 1824 treaty with Stephen F. Austin and their semi-sedentary lifestyle.[49] Archaeological investigations at the Stone site (41ML38), known historically as El Quiscat's Village from Athanase de Mézières' 1770s expeditions, have revealed artifacts such as pottery, stone tools, and structural remains consistent with Waco occupation on a horseshoe bend of the Brazos.[50] Spanish records from 1772 first documented Waco settlements during de Mézières' upstream journey, describing multiple villages in the region.[1] At Waco Lake, excavations of sites including Britton (41ML37), McMillan (41ML162), and Higginbotham (41ML195) uncovered prehistoric features like burned rock middens, basin hearths, and macrobotanical remains indicative of intensive plant processing, situating the area within Central Texas archeological traditions that preceded and overlapped with Waco presence; the Waco Lake vicinity hosts the nearest confirmed Hueco (Waco) village to modern tribal lands.[51] [52] [6] The Waco Indian Village Live Oak Grove at 701 Jefferson Avenue preserves ancient live oaks that overlooked the village, accompanied by a 1936 Texas Centennial marker commemorating the site's significance.[25] Indian Spring Park, adjacent to the Waco Suspension Bridge on the Brazos, marks natural springs that served as a key resource and gathering point for the Waco, drawing them for water amid abundant local flora and fauna.[53]