Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cherokee

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

The Cherokee (/ˈtʃɛrəkiː/ CHEH-rə-kee, /ˌtʃɛrəˈkiː/ ⓘ CHEH-rə-KEE;[8][9] Cherokee: ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, romanized: Aniyvwiyaʔi / Anigiduwagi, or ᏣᎳᎩ, Tsalagi) people are one of the Indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, they were concentrated in their homelands, in towns along river valleys of what is now southwestern North Carolina, southeastern Tennessee, southwestern Virginia, edges of western South Carolina, northern Georgia and northeastern Alabama with hunting grounds in Kentucky, together consisting of around 40,000 square miles.[10]

The Cherokee language is part of the Iroquoian language group. In the 19th century, James Mooney, an early American ethnographer, recorded one oral tradition that told of the tribe having migrated south in ancient times from the Great Lakes region, where other Iroquoian peoples have been based.[11] However, anthropologist Thomas R. Whyte, writing in 2007, dated the split among the peoples as occurring earlier. He believes that the origin of the proto-Iroquoian language was likely the Appalachian region, and the split between Northern and Southern Iroquoian languages began 4,000 years ago.[12]

By the 19th century, White American settlers had classified the Cherokee of the Southeast as one of the "Five Civilized Tribes" in the region. They were agrarian, lived in permanent villages and had begun to adopt some cultural and technological practices of the white settlers. They also developed their own writing system.

Today three Cherokee tribes are federally recognized: the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians (UKB) in Oklahoma, the Cherokee Nation (CN) in Oklahoma, and the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians (EBCI) in North Carolina.[13]

The Cherokee Nation has more than 300,000 tribal citizens, making it the largest of the 574 federally recognized tribes in the United States.[14] In addition, numerous groups claim Cherokee lineage, and some of these are state-recognized. A total of more than 819,000 people are estimated to have identified as having Cherokee ancestry on the U.S. census; most are not enrolled citizens of any tribe.[2]

Of the three federally recognized Cherokee tribes, the Cherokee Nation and the UKB have headquarters in Tahlequah, Oklahoma, and most of their citizens live in the state. The UKB are mostly descendants of "Old Settlers", also called Western Cherokee: those who migrated from the Southeast to Arkansas and Oklahoma in about 1817, prior to Indian removal. They are related to the Cherokee who were later forcibly relocated there in the 1830s under the Indian Removal Act. The Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians is located on land known as the Qualla Boundary in western North Carolina. They are mostly descendants of ancestors who had resisted or avoided relocation, remaining in the area. Because they gave up tribal citizenship at the time, they became state and US citizens. In the late 19th century, they reorganized as a federally recognized tribe.[15]

Etymology

[edit]A Cherokee-language name for Cherokee people is Aniyvwiya (ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯ, translating as 'Principal People').[16] Another endonym is Anigiduwagi (ᎠᏂᎩᏚᏩᎩ, translating as 'People from Kituwah').[17] Tsalagi Gawonihisdi (ᏣᎳᎩ ᎦᏬᏂᎯᏍᏗ) is the Cherokee name for the Cherokee language.[18][19]

Many theories, though all unproven, abound about the origin of the name Cherokee. It may have originally been derived from one of the competitive tribes in the area.

The earliest Spanish transliteration of the name, from 1755, is recorded as Tchalaque, but it dates to accounts related to the Hernando de Soto expedition in the mid-16th century.[20] Another theory is that Cherokee derives from the Lower Creek word Cvlakke ("chuh-log-gee"), as the Creek were also in this mountainous region.[21]

The Iroquois Five Nations, historically based in New York and Pennsylvania, called the Cherokee Oyata'ge'ronoñ ('inhabitants of the cave country').[22] It is possible the word Cherokee comes from a Muscogee Creek word meaning 'people of different speech', because the two peoples spoke different languages.[23] Jack Kilpatrick disputes this idea, noting that he believes the name come from the Cherokee word tsàdlagí meaning 'he has turned aside'.

Origins

[edit]

Anthropologists and historians have two main theories of Cherokee origins. One is that the Cherokee, an Iroquoian-speaking people, migrated to Southern Appalachia from northern areas around the Great Lakes in late prehistoric times.[clarify] The area became territory of the Iroquois (also known as the "Haudenosaunee") nations and other Iroquoian-speaking peoples of the Southeast such as the Tuscarora people of the Carolinas, and the Meherrin and Nottaway of Virginia. The other theory is that the Cherokee had been in the Southeast for thousands of years and that proto-Iroquoian developed there instead of in the north.

Supporting the first theory are recorded conversations of Cherokee elders made by ethnographer James Mooney in the late 19th century, who recounted an oral tradition of their people migrating south from the Great Lakes region in ancient times.[11] They occupied territories where earthwork platform mounds were built by peoples during the earlier Woodland period.

The people of the Middle Woodland period are believed to be ancestors of the historic Cherokee and occupied what is now Western North Carolina, circa 200 to 600 CE. They are believed to have built what is called the Biltmore Mound, found in 1984 south of the Swannanoa River on the Biltmore Estate, which has numerous Native American sites.[24]

Other ancestors of the Cherokee are considered to be part of the later Pisgah phase of South Appalachian Mississippian culture, a regional variation of the Mississippian culture that arose circa 1000 and lasted to 1500 CE.[25] There is a consensus among most specialists in Southeast archeology and anthropology about these dates. But Finger says that ancestors of the Cherokee people lived in western North Carolina and eastern Tennessee for a far longer period of time.[26] Additional mounds were built by peoples during this cultural phase. Typically in this region, towns had a single platform mound and served as a political center for smaller villages.

Homelands

[edit]The Cherokee occupied numerous towns throughout the river valleys and mountain ridges of their homelands. What were called the Lower towns were found in what is present-day western Oconee County, South Carolina, along the Keowee River (called the Savannah River in its lower portion). The principal town of the Lower Towns was Keowee. Other Cherokee towns on the Keowee River included Estatoe and Sugartown (Kulsetsiyi), a name repeated in other areas.

In western North Carolina, what were known as the Valley, Middle, and Outer Towns were located along the major rivers of the Tuckasegee, the upper Little Tennessee, Hiwasee, French Broad and other systems. The Overhill Cherokee occupied towns along the lower Little Tennessee River and upper Tennessee River on the western side of the Appalachian Mountains, in present-day southeastern Tennessee.

Agriculture

[edit]During the late Archaic and Woodland Period, Native Americans in the region began to cultivate plants such as marsh elder, lambsquarters, pigweed, sunflowers, and some native squash. People created new art forms such as shell gorgets, adopted new technologies, and developed an elaborate cycle of religious ceremonies.

During the Mississippian culture-period (1000 to 1500 CE in the regional variation known as the South Appalachian Mississippian culture), local women developed a new variety of maize (corn) called eastern flint corn. It closely resembled modern corn and produced larger crops. The successful cultivation of corn surpluses allowed the rise of larger, more complex chiefdoms consisting of several villages and concentrated populations during this period. Corn became celebrated among numerous peoples in religious ceremonies, especially the Green Corn Ceremony.

Early culture

[edit]Much of what is known about pre-18th century Native American cultures has come from records of Spanish expeditions. The earliest ones of the mid-16th century encountered peoples of the Mississippian culture era, who were ancestral to tribes that emerged in the Southeast, such as the Cherokee, Muscogee, Cheraw, and Catawba. Specifically in 1540–41, a Spanish expedition led by Hernando de Soto passed through present-day South Carolina, proceeding into western North Carolina and what is considered Cherokee country. The Spanish recorded a Chalaque[28] people as living around the Keowee River, where western North Carolina, South Carolina, and northeastern Georgia meet. The Cherokee consider this area to be part of their homelands, which also extended into southeastern Tennessee.[29]

Further west, De Soto's expedition visited villages in present-day northwestern Georgia, recording them as ruled at the time by the Coosa chiefdom. This is believed to be a chiefdom ancestral to the Muscogee Creek people, who developed as a Muskogean-speaking people with a distinct culture.[30]

In 1566, the Juan Pardo expedition traveled from the present-day South Carolina coast into its interior, and into western North Carolina and southeastern Tennessee. He recorded meeting Cherokee-speaking people who visited him while he stayed at the Joara chiefdom (north of present-day Morganton, North Carolina). The historic Catawba later lived in this area of the upper Catawba River. Pardo and his forces wintered over at Joara, building Fort San Juan there in 1567.

His expedition proceeded into the interior, noting villages near modern Asheville and other places that are part of the Cherokee homelands. According to anthropologist Charles M. Hudson, the Pardo expedition also recorded encounters with Muskogean-speaking peoples at Chiaha in southeastern modern Tennessee.

Linguistic studies

[edit]Linguistic studies have been another way for researchers to study the development of people and their cultures. Unlike most other Native American tribes in the American Southeast at the start of the historic era, the Cherokee and Tuscarora people spoke Iroquoian languages. Since the Great Lakes region was the territory of most Iroquoian-language speakers, scholars have theorized that both the Cherokee and Tuscarora migrated south from that region. The Cherokee oral history tradition supports their migration from the Great Lakes.

Linguistic analysis shows a relatively large difference between Cherokee and the northern Iroquoian languages, suggesting they had migrated long ago. Scholars posit a split between the groups in the distant past, perhaps 3,500–3,800 years ago.[31] Glottochronology studies suggest the split occurred between about 1500 and 1800 BCE.[32] The Cherokee say that the ancient settlement of Kituwa on the Tuckasegee River is their original settlement in the Southeast.[31] It was formerly adjacent to and is now part of Qualla Boundary (the base of the federally recognized Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians) in North Carolina.

According to Thomas Whyte, who posits that proto-Iroquoian developed in Appalachia, the Cherokee and Tuscarora broke off in the Southeast from the major group of Iroquoian speakers who migrated north to the Great Lakes area. There a succession of Iroquoian-speaking tribes were encountered by Europeans in historic times.

Other sources of early Cherokee history

[edit]In the 1830s, the American writer John Howard Payne visited Cherokee then based in Georgia. He recounted what they shared about pre-19th-century Cherokee culture and society. For instance, the Payne papers describe the account by Cherokee elders of a traditional two-part societal structure. A "white" organization of elders represented the seven clans. As Payne recounted, this group, which was hereditary and priestly, was responsible for religious activities, such as healing, purification, and prayer. A second group of younger men, the "red" organization, was responsible for warfare. The Cherokee considered warfare a polluting activity.[33]

Researchers have debated the reasons for the change. Some historians believe the decline in priestly power originated with a revolt by the Cherokee against the abuses of the priestly class known as the Ani-kutani.[34] Ethnographer James Mooney, who studied and talked with the Cherokee in the late 1880s, was the first to trace the decline of the former hierarchy to this revolt.[35] By the time that Mooney was studying the people in the late 1880s, the structure of Cherokee religious practitioners was more informal, based more on individual knowledge and ability than upon heredity.[34]

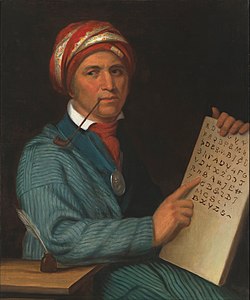

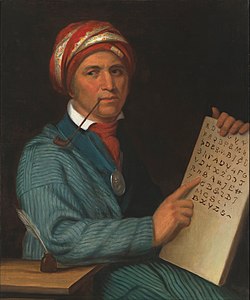

Another major source of early cultural history comes from materials written in the 19th century by the didanvwisgi (ᏗᏓᏅᏫᏍᎩ), Cherokee medicine men, after Sequoyah's creation of the Cherokee syllabary in the 1820s. Initially only the didanvwisgi learned to write and read such materials, which were considered extremely powerful in a spiritual sense.[34] Later, the syllabary and writings were widely adopted by the Cherokee people.

History

[edit]17th century: English contact

[edit]In 1657, there was a disturbance in Virginia Colony as the Rechahecrians or Rickahockans, as well as the Siouan Manahoac and Nahyssan, broke through the frontier and settled near the Falls of the James River, near present-day Richmond, Virginia. The following year, a combined force of English colonists and Pamunkey drove the newcomers away. The identity of the Rechahecrians has been much debated. Historians noted the name closely resembled that recorded for the Eriechronon or Erielhonan, commonly known as the Erie tribe, another Iroquoian-speaking people based south of the Great Lakes in present-day northern Pennsylvania.[36] This Iroquoian people had been driven away from the southern shore of Lake Erie in 1654 by the powerful Iroquois Five Nations, also known as Haudenosaunee, who were seeking more hunting grounds to support their dominance in the beaver fur trade. The anthropologist Martin Smith theorized some remnants of the tribe migrated to Virginia after the wars (1986:131–32), later becoming known as the Westo to English colonists in the Province of Carolina. A few historians suggest this tribe was Cherokee.[37]

Virginian traders developed a small-scale trading system with the Cherokee in the Piedmont before the end of the 17th century. The earliest recorded Virginia trader to live among the Cherokee was Cornelius Dougherty or Dority, in 1690.[38][39]

18th century

[edit]

The Cherokee gave sanctuary to a band of Shawnee in the 1660s. But from 1710 to 1715, the Cherokee and Chickasaw allied with the British, and fought the Shawnee, who were allied with French colonists, forcing the Shawnee to move northward.[40]

The Cherokee fought with the Yamasee, Catawba, and British in late 1712 and early 1713 against the Tuscarora in the Second Tuscarora War. The Tuscarora War marked the beginning of a British-Cherokee relationship that, despite breaking down on occasion, remained strong for much of the 18th century. With the growth of the deerskin trade, the Cherokee were considered valuable trading partners, since deer skins from the cooler country of their mountain hunting-grounds were of better quality than those supplied by the lowland coastal tribes, who were neighbors of the English colonists.

In January 1716, Cherokee murdered a delegation of Muscogee Creek leaders at the town of Tugaloo, marking their entry into the Yamasee War. It ended in 1717 with peace treaties between the colony of South Carolina and the Creek. Hostility and sporadic raids between the Cherokee and Creek continued for decades.[41] These raids came to a head at the Battle of Taliwa in 1755, at present-day Ball Ground, Georgia, with the defeat of the Muscogee.

In 1721, the Cherokee ceded lands in South Carolina. In 1730, at Nikwasi, a Cherokee town and Mississippian culture site, a Scots adventurer, Sir Alexander Cuming, crowned Moytoy of Tellico as "Emperor" of the Cherokee. Moytoy agreed to recognize King George II of Great Britain as the Cherokee protector. Cuming arranged to take seven prominent Cherokee, including Attakullakulla, to London, England. There the Cherokee delegation signed the Treaty of Whitehall with the British. Moytoy's son, Amo-sgasite (Dreadful Water), attempted to succeed him as "Emperor" in 1741, but the Cherokee elected their own leader, Conocotocko (Old Hop) of Chota.[42]

Political power among the Cherokee remained decentralized, and towns acted autonomously. In 1735, the Cherokee were said to have 64 towns and villages, with an estimated fighting force of 6,000 men.[43] In 1738 and 1739, smallpox epidemics broke out among the Cherokee, who had no natural immunity to the new infectious disease. Nearly half their population died within a year. Hundreds of other Cherokee committed suicide due to their losses and disfigurement from the disease.

British colonial officer Henry Timberlake, born in Virginia, described the Cherokee people as he saw them in 1761:

The Cherokees are of a middle stature, of an olive colour, tho' generally painted, and their skins stained with gun-powder, pricked into it in very pretty figures. The hair of their head is shaved, tho' many of the old people have it plucked out by the roots, except a patch on the hinder part of the head, about twice the bigness of a crown-piece, which is ornamented with beads, feathers, wampum, stained deer hair, and such like baubles. The ears are slit and stretched to an enormous size, putting the person who undergoes the operation to incredible pain, being unable to lie on either side for nearly forty days. To remedy this, they generally slit but one at a time; so soon as the patient can bear it, they wound round with wire to expand them, and are adorned with silver pendants and rings, which they likewise wear at the nose. This custom does not belong originally to the Cherokees, but taken by them from the Shawnese, or other northern nations. They that can afford it wear a collar of wampum, which are beads cut out of clam-shells, a silver breast-plate, and bracelets on their arms and wrists of the same metal, a bit of cloth over their private parts, a shirt of the English make, a sort of cloth-boots, and mockasons (sic), which are shoes of a make peculiar to the Americans, ornamented with porcupine-quills; a large mantle or match-coat thrown over all complete their dress at home ...[44]

From 1753 to 1755, battles broke out between the Cherokee and Muscogee over disputed hunting grounds in North Georgia. The Cherokee were victorious in the Battle of Taliwa. British soldiers built forts in Cherokee country to defend against the French in the Seven Years' War, which was fought across Europe and was called the French and Indian War on the North American front. These included Fort Loudoun near Chota on the Tennessee River in eastern Tennessee. Serious misunderstandings arose quickly between the two allies, resulting in the 1760 Anglo-Cherokee War.[45]

King George III's Royal Proclamation of 1763 forbade British settlements west of the Appalachian crest, as his government tried to afford some protection from colonial encroachment to the Cherokee and other tribes they depended on as allies. The Crown found the ruling difficult to enforce with colonists.[45]

From 1771 to 1772, North Carolinian settlers squatted on Cherokee lands in Tennessee, forming the Watauga Association.[46] Daniel Boone and his party tried to settle in Kentucky, but the Shawnee, Delaware, Mingo, and some Cherokee attacked a scouting and forage party that included Boone's son, James Boone, and William Russell's son, Henry, who were killed in the skirmish.[47]

In 1776, allied with the Shawnee led by Cornstalk, Cherokee attacked settlers in South Carolina, Georgia, Virginia, and North Carolina in the Second Cherokee War. Overhill Cherokee Nancy Ward, Dragging Canoe's cousin, warned settlers of impending attacks. Provincial militias retaliated, destroying more than 50 Cherokee towns. North Carolina militia in 1776 and 1780 invaded and destroyed the Overhill towns in what is now Tennessee. In 1777, surviving Cherokee town leaders signed treaties with the new states.

Dragging Canoe and his band settled along Chickamauga Creek near present-day Chattanooga, Tennessee, where they established 11 new towns. Chickamauga Town was his headquarters and the colonists tended to call his entire band the Chickamauga to distinguish them from other Cherokee. From here he fought a guerrilla war against settlers, which lasted from 1776 to 1794. These are known informally as the Cherokee–American wars, but this is not a historian's term.

The first Treaty of Tellico Blockhouse, signed November 7, 1794, finally brought peace between the Cherokee and Americans, who had achieved independence from the British Crown. In 1805, the Cherokee ceded their lands between the Cumberland and Duck rivers (i.e. the Cumberland Plateau) to Tennessee.

Scots (and other Europeans) among the Cherokee in the 18th century

[edit]The traders and British government agents dealing with the southern tribes in general, and the Cherokee in particular, were nearly all of Scottish ancestry, with many documented as being from the Highlands. A few were Scotch-Irish, English, French, and German (see Scottish Indian trade). Many of these men married women from their host peoples and remained after the fighting had ended. Some of their mixed-race children, who were raised in Native American cultures, later became significant leaders among the Five Civilized Tribes of the Southeast.[48]

Notable traders, agents, and refugee Tories among the Cherokee included John Stuart, Henry Stuart, Alexander Cameron, John McDonald, John Joseph Vann (father of James Vann), Daniel Ross (father of John Ross), John Walker Sr., Mark Winthrop Battle, John McLemore (father of Bob), William Buchanan, John Watts (father of John Watts Jr.), John D. Chisholm, John Benge (father of Bob Benge), Thomas Brown, John Rogers (Welsh), John Gunter (German, founder of Gunter's Landing), James Adair (Irish), William Thorpe (English), and Peter Hildebrand (German), among many others. Some attained the honorary status of minor chiefs and/or members of significant delegations.

By contrast, a large portion of the settlers encroaching on the Native American territories were Scotch-Irish, Irish from Ulster who were of Scottish descent and had been part of the plantation of Ulster. They also tended to support the Revolution. But in the back country, there were also Scotch-Irish who were Loyalists, such as Simon Girty.

19th century

[edit]Acculturation

[edit]The Cherokee lands between the Tennessee and Chattahoochee rivers were remote enough from white settlers to remain independent after the Cherokee–American wars. The deerskin trade was no longer feasible on their greatly reduced lands, and over the next several decades, the people of the fledgling Cherokee Nation began to build a new society modeled on the white Southern United States.

George Washington sought to 'civilize' Southeastern Native Americans, through programs overseen by the Indian Agent Benjamin Hawkins. He encouraged the Cherokee to abandon their communal land-tenure and settle on individual farmsteads, which was facilitated by the destruction of many American Indian towns during the American Revolutionary War. The deerskin trade brought white-tailed deer to the brink of extinction, and as pigs and cattle were introduced, they became the principal sources of meat. The government supplied the tribes with spinning wheels and cotton-seed, and men were taught to fence and plow the land, in contrast to their traditional division in which crop cultivation was woman's labor. Americans instructed the women in weaving. Eventually, Hawkins helped them set up smithies, gristmills and cotton plantations.

The Cherokee organized a national government under Principal Chiefs Little Turkey (1788–1801), Black Fox (1801–1811), and Pathkiller (1811–1827), all former warriors of Dragging Canoe. The 'Cherokee triumvirate' of James Vann and his protégés The Ridge and Charles R. Hicks advocated acculturation, formal education, and modern methods of farming. In 1801 they invited Moravian missionaries from North Carolina to teach Christianity and the 'arts of civilized life.' The Moravians and later Congregationalist missionaries ran boarding schools, and a select few students were educated at the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions school in Connecticut.

In 1806 a Federal Road from Savannah, Georgia, to Knoxville, Tennessee, was built through Cherokee land. Chief James Vann opened a tavern, inn and ferry across the Chattahoochee and built a cotton-plantation on a spur of the road from Athens, Georgia, to Nashville. His son 'Rich Joe' Vann developed the plantation to 800 acres (3.2 km2), cultivated by 150 slaves. He exported cotton to England, and owned a steamboat on the Tennessee River.[49]

The Cherokee allied with the U.S. against the nativist and pro-British Red Stick faction of the Upper Creek in the Creek War during the War of 1812. Cherokee warriors led by Major Ridge played a major role in General Andrew Jackson's victory at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend. Major Ridge moved his family to Rome, Georgia, where he built a substantial house, developed a large plantation and ran a ferry on the Oostanaula River. Although he never learned English, he sent his son and nephews to New England to be educated in mission schools. His interpreter and protégé Chief John Ross, the descendant of several generations of Cherokee women and Scots fur-traders, built a plantation and operated a trading firm and a ferry at Ross' Landing (Chattanooga, Tennessee). During this period, divisions arose between the acculturated elite and the great majority of Cherokee, who clung to traditional ways of life.

Around 1809 Sequoyah began developing a written form of the Cherokee language. He spoke no English, but his experiences as a silversmith dealing regularly with white settlers, and as a warrior at Horseshoe Bend, convinced him the Cherokee needed to develop writing. In 1821, he introduced Cherokee syllabary, the first written syllabic form of an American Indian language outside of Central America. Initially, his innovation was opposed by both Cherokee traditionalists and white missionaries, who sought to encourage the use of English. When Sequoyah taught children to read and write with the syllabary, he reached the adults. By the 1820s, the Cherokee had a higher rate of literacy than the whites around them in Georgia.

In 1819, the Cherokee began holding council meetings at New Town, at the headwaters of the Oostanaula (near present-day Calhoun, Georgia). In November 1825, New Town became the capital of the Cherokee Nation, and was renamed New Echota, after the Overhill Cherokee principal town of Chota.[50] Sequoyah's syllabary was adopted. They had developed a police force, a judicial system, and a National Committee.

In 1827, the Cherokee Nation drafted a Constitution modeled on the United States, with executive, legislative and judicial branches and a system of checks and balances. The two-tiered legislature was led by Major Ridge and his son John Ridge. Convinced the tribe's survival required English-speaking leaders who could negotiate with the U.S., the legislature appointed John Ross as Principal Chief. A printing press was established at New Echota by the Vermont missionary Samuel Worcester and Major Ridge's nephew Elias Boudinot, who had taken the name of his white benefactor, a leader of the Continental Congress and New Jersey Congressman. They translated the Bible into Cherokee syllabary. Boudinot published the first edition of the bilingual 'Cherokee Phoenix,' the first American Indian newspaper, in February 1828.[51]

Removal era

[edit]

Before the final removal to present-day Oklahoma, many Cherokees relocated to present-day Arkansas, Missouri and Texas.[52] Between 1775 and 1786 the Cherokee, along with people of other nations such as the Choctaw and Chickasaw, began voluntarily settling along the Arkansas and Red Rivers.[53]

In 1802, the federal government promised to extinguish Indian titles to lands claimed by Georgia in return for Georgia's cession of the western lands that became Alabama and Mississippi. To convince the Cherokee to move voluntarily in 1815, the US government established a Cherokee Reservation in Arkansas.[54] The reservation boundaries extended from north of the Arkansas River to the southern bank of the White River. Di'wali (The Bowl), Sequoyah, Spring Frog and Tatsi (Dutch) and their bands settled there. These Cherokees became known as "Old Settlers."

The Cherokee eventually migrated as far north as the Missouri Bootheel by 1816. They lived interspersed among the Delawares and Shawnees of that area.[55] The Cherokee in Missouri Territory increased rapidly in population, from 1,000 to 6,000 over the next year (1816–1817), according to reports by Governor William Clark.[56] Increased conflicts with the Osage Nation led to the Battle of Claremore Mound and the eventual establishment of Fort Smith between Cherokee and Osage communities.[57] In the Treaty of St. Louis (1825), the Osage were made to "cede and relinquish to the United States, all their right, title, interest, and claim, to lands lying within the State of Missouri and Territory of Arkansas ..." to make room for the Cherokee and the Mashcoux, Muscogee Creeks.[58] As late as the winter of 1838, Cherokee and Creek living in the Missouri and Arkansas areas petitioned the War Department to remove the Osage from the area.[59]

A group of Cherokee traditionalists led by Di'wali moved to Spanish Texas in 1819. Settling near Nacogdoches, they were welcomed by Mexican authorities as potential allies against Anglo-American colonists. The Texas Cherokees were mostly neutral during the Texas War of Independence. In 1836, they signed a treaty with Texas President Sam Houston, an adopted member of the Cherokee tribe. His successor Mirabeau Lamar sent militia to evict them in 1839.

Trail of Tears

[edit]

Following the War of 1812, and the concurrent Red Stick War, the U.S. government persuaded several groups of Cherokee to a voluntary removal to the Arkansas Territory. These were the "Old Settlers", the first of the Cherokee to make their way to what would eventually become Indian Territory (modern day Oklahoma). This effort was headed by Indian Agent Return J. Meigs, and was finalized with the signing of the Jackson and McMinn Treaty, giving the Old Settlers undisputed title to the lands designated for their use.[60]

During this time, Georgia focused on removing the Cherokee's neighbors, the Lower Creek. Georgia Governor George Troup and his cousin William McIntosh, chief of the Lower Creek, signed the Treaty of Indian Springs in 1825, ceding the last Muscogee (Creek) lands claimed by Georgia. The state's northwestern border reached the Chattahoochee, the border of the Cherokee Nation. In 1829, gold was discovered at Dahlonega, on Cherokee land claimed by Georgia. The Georgia Gold Rush was the first in U.S. history, and state officials demanded that the federal government expel the Cherokee. When Andrew Jackson was inaugurated as president in 1829, Georgia gained a strong ally in Washington. In 1830 Congress passed the Indian Removal Act, authorizing the forcible relocation of American Indians east of the Mississippi to a new Indian Territory.

Jackson claimed the removal policy was an effort to prevent the Cherokee from facing extinction as a people, which he considered the fate that "...the Mohegan, the Narragansett, and the Delaware" had suffered.[61] There is, however, ample evidence that the Cherokee were adapting to modern farming techniques. A modern analysis shows that the area was in general in a state of economic surplus and could have accommodated both the Cherokee and new settlers.[62]

The Cherokee brought their grievances to a US judicial review that set a precedent in Indian country. John Ross traveled to Washington, D.C., and won support from National Republican Party leaders Henry Clay and Daniel Webster. Samuel Worcester campaigned on behalf of the Cherokee in New England, where their cause was taken up by Ralph Waldo Emerson (see Emerson's 1838 letter to Martin Van Buren). In June 1830, a delegation led by Chief Ross defended Cherokee rights before the U.S. Supreme Court in Cherokee Nation v. Georgia.

In 1831, Georgia militia arrested Samuel Worcester for residing on Indian lands without a state permit, imprisoning him in Milledgeville. In Worcester v. Georgia (1832), the US Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall ruled that American Indian nations were "distinct, independent political communities retaining their original natural rights," and entitled to federal protection from the actions of state governments that infringed on their sovereignty.[63] Worcester v. Georgia is considered one of the most important dicta in law dealing with Native Americans.

Jackson ignored the Supreme Court's ruling, as he needed to conciliate Southern sectionalism during the era of the Nullification Crisis. His landslide reelection in 1832 emboldened calls for Cherokee removal. Georgia sold Cherokee lands to its citizens in a Land Lottery, and the state militia occupied New Echota. The Cherokee National Council, led by John Ross, fled to Red Clay, a remote valley north of Georgia's land claim. Ross had the support of Cherokee traditionalists, who could not imagine removal from their ancestral lands.

A small group known as the "Ridge Party" or the "Treaty Party" saw relocation as inevitable and believed the Cherokee Nation needed to make the best deal to preserve their rights in Indian Territory. Led by Major Ridge, John Ridge and Elias Boudinot, they represented the Cherokee elite, whose homes, plantations and businesses were confiscated, or under threat of being taken by white squatters with Georgia land-titles. With capital to acquire new lands, they were more inclined to accept relocation. On December 29, 1835, the "Ridge Party" signed the Treaty of New Echota, stipulating terms and conditions for the removal of the Cherokee Nation. In return for their lands, the Cherokee were promised a large tract in the Indian Territory, $5 million, and $300,000 for improvements on their new lands.[64]

John Ross gathered over 15,000 signatures for a petition to the U.S. Senate, insisting that the treaty was invalid because it did not have the support of the majority of the Cherokee people. The Senate passed the Treaty of New Echota by a one-vote margin. It was enacted into law in May 1836.[65]

Two years later, President Martin Van Buren ordered 7,000 federal troops and state militia under General Winfield Scott into Cherokee lands to evict the tribe. Over 16,000 Cherokee were forcibly relocated westward to Indian Territory in 1838–1839, a migration known as the Trail of Tears or in Cherokee ᏅᎾ ᏓᎤᎳ ᏨᏱ or Nvna Daula Tsvyi (The Trail Where They Cried), although it is described by another word Tlo-va-sa (The Removal). Marched over 800 miles (1,300 km) across Tennessee, Kentucky, Illinois, Missouri and Arkansas, the people suffered from disease, exposure and starvation, and as many as 4,000 died, nearly a fifth of the population.[66] As some Cherokees were slaveholders, they took enslaved African Americans with them west of the Mississippi. Intermarried European Americans and missionaries also walked the Trail of Tears. Ross preserved a vestige of independence by negotiating permission for the Cherokee to conduct their own removal under U.S. supervision.[67]

In keeping with the tribe's "blood law" that prescribed the death penalty for Cherokee who sold lands, Ross's son arranged the murder of the leaders of the "Treaty Party". On June 22, 1839, a party of twenty-five Ross supporters assassinated Major Ridge, John Ridge and Elias Boudinot. The party included Daniel Colston, John Vann, Archibald, James and Joseph Spear. Boudinot's brother Stand Watie fought and survived that day, escaping to Arkansas.

In 1827, Sequoyah had led a delegation of Old Settlers to Washington, D.C., to negotiate for the exchange of Arkansas land for land in Indian Territory. After the Trail of Tears, he helped mediate divisions between the Old Settlers and the rival factions of the more recent arrivals. In 1839, as President of the Western Cherokee, Sequoyah signed an Act of Union with John Ross that reunited the two groups of the Cherokee Nation.

Eastern Band

[edit]

The Cherokee living along the Oconaluftee River in the Great Smoky Mountains were the most conservative and isolated from European–American settlements. They rejected the reforms of the Cherokee Nation. When the Cherokee government ceded all territory east of the Little Tennessee River to North Carolina in 1819, they withdrew from the Nation.[68] William Holland Thomas, a white store owner and state legislator from Jackson County, North Carolina, helped over 600 Cherokee from Qualla Town obtain North Carolina citizenship, which exempted them from forced removal. Over 400 Cherokee either hid from Federal troops in the remote Snowbird Mountains, under the leadership of Tsali (ᏣᎵ),[69] or belonged to the former Valley Towns area around the Cheoah River who negotiated with the state government to stay in North Carolina. An additional 400 Cherokee stayed on reserves in Southeast Tennessee, North Georgia, and Northeast Alabama, as citizens of their respective states. Together, these groups were the ancestors of the federally recognized Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, and some of the state-recognized tribes in surrounding states.

Civil War

[edit]

The American Civil War was devastating for both East and Western Cherokee. The Eastern Band, aided by William Thomas, became the Thomas Legion of Cherokee Indians and Highlanders, fighting for the Confederacy in the American Civil War.[70] Cherokee in Indian Territory divided into Union and Confederate factions.

Stand Watie, the leader of the Ridge Party, raised a regiment for Confederate service in 1861. John Ross, who had reluctantly agreed to ally with the Confederacy, was captured by Federal troops in 1862. He lived in a self-imposed exile in Philadelphia, supporting the Union. In the Indian Territory, the national council of those who supported the Union voted to abolish slavery in the Cherokee Nation in 1863, but they were not the majority slaveholders and the vote had little effect on those supporting the Confederacy.

Watie was elected Principal Chief of the pro-Confederacy majority. A master of hit-and-run cavalry tactics, Watie fought those Cherokee loyal to John Ross and Federal troops in Indian Territory and Arkansas, capturing Union supply trains and steamboats, and saving a Confederate army by covering their retreat after the Battle of Pea Ridge in March 1862. He became a Brigadier General of the Confederate States; the only other American Indian to hold the rank in the American Civil War was Ely S. Parker with the Union Army. On June 25, 1865, two months after Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox, Stand Watie became the last Confederate General to stand down.

Reconstruction and late 19th century

[edit]

After the Civil War, the U.S. government required the Cherokee Nation to sign a new treaty, because of its alliance with the Confederacy. The U.S. required the 1866 Treaty to provide for the emancipation of all Cherokee slaves, and full citizenship to all Cherokee Freedmen and all African Americans who chose to continue to reside within tribal lands, so that they "shall have all the rights of native Cherokees."[71] Both before and after the Civil War, some Cherokee intermarried or had relationships with African Americans, just as they had with whites. Many Cherokee Freedmen have been active politically within the tribe.

The US government also acquired easement rights to the western part of the territory, which became the Oklahoma Territory, for the construction of railroads. Development and settlers followed the railroads. By the late 19th century, the government believed that Native Americans would be better off if each family owned its own land. The Dawes Act of 1887 provided for the breakup of commonly held tribal land into individual household allotments. Native Americans were registered on the Dawes Rolls and allotted land from the common reserve. The U.S. government counted the remainder of tribal land as "surplus" and sold it to non-Cherokee individuals.

The Curtis Act of 1898 dismantled tribal governments, courts, schools, and other civic institutions. For Indian Territory, this meant the abolition of the Cherokee courts and governmental systems. This was seen as necessary before the Oklahoma and Indian territories could be admitted as a combined state. In 1905, the Five Civilized Tribes of the Indian Territory proposed the creation of the State of Sequoyah as one to be exclusively Native American but failed to gain support in Washington, D.C.. In 1907, the Oklahoma and Indian Territories entered the union as the state of Oklahoma.

By the late 19th century, the Eastern Band of Cherokee were laboring under the constraints of a segregated society. In the aftermath of Reconstruction, conservative white Democrats regained power in North Carolina and other southern states. They proceeded to effectively disenfranchise all blacks and many poor whites by new constitutions and laws related to voter registration and elections. They passed Jim Crow laws that divided society into "white" and "colored", mostly to control freedmen. Cherokee and other Native Americans were classified on the colored side and suffered the same racial segregation and disenfranchisement as former slaves. They also often lost their historical documentation for identification as Indians, when the Southern states classified them as colored. Black Americans and Native Americans would not have their constitutional rights as U.S. citizens enforced until after the Civil Rights Movement secured passage of civil rights legislation in the mid-1960s, and the federal government began to monitor voter registration and elections, as well as other programs.[citation needed]

Tribal land jurisdiction status

[edit]On July 9, 2020, the United States Supreme Court decided in the McGirt v Oklahoma decision in a criminal jurisdiction case that roughly half the land of the state of Oklahoma made up of tribal nations like the Cherokee are officially Native American tribal land jurisdictions.[72] Oklahoma Governor Kevin Stitt, himself a Cherokee Nation citizen, sought to reverse the Supreme Court decision. The following year, the state of Oklahoma couldn't block federal action to grant the Cherokee Nation—along with the Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee (Creek), and Seminole Nations—reservation status.[73]

Population history

[edit]John R. Swanton enumerates 201 Cherokee villages and towns.[74] The Cherokee had 6,000 warriors (and therefore around 30,000 people) in years 1730–35 according to J. Adair. In 1738 they also had 6,000 warriors, but down to 5,000 in 1740 (according to Ga. Hist. Coll., II). Colonel James Oglethorpe confirms that they had 5,000 warriors in 1739 (Ga. Coll. Rec., V). Also according to Ga. Coll. Rec., V an epidemic reduced them "by almost one-half" in 1738, but this source doesn't specify how numerous they were before the epidemic. Perhaps this source exaggerates the casualties caused by that epidemic, and in fact it killed just around 1,000 warriors. Arthur Dobbs estimated the Cherokee warrior strength in 1755 at 2,590 (but W. Douglas at about the same time reported 6,000 warriors). In 1761 soon after the end of the Anglo-Cherokee War there were 2,300 warriors according to J. Adair. By year 1768 their number recovered back to 3,000 warriors, and B. R. Carroll in "Historical Collections of South Carolina" also reported that they had 3,000 warriors.[75] By 1819 there were 4,000 warriors (and therefore around 20,000 people - including about 5,000 to the west of the Mississippi). George Catlin estimated 22,000 Cherokees in 1832, before their removal. But according to a report by the Commissioner of Indian Affairs dated November 25, 1841, the number of Cherokees who had already been removed west of the Mississippi (to Oklahoma, Indian Territory) was 25,911.[76] Henry Schoolcraft reported 21,707 Cherokees in 1857. Indian Affairs 1861 reported 22,000. Enumeration published in 1886 counted 23,000 Cherokee in Oklahoma (Indian Territory) as of year 1884.[77] Indian Affairs reported in 1890 around 25,000 among the Western Cherokee (in Oklahoma) and in years 1884 and 1889 around 3,000 among the Eastern Cherokee. The Cherokee national census of 1890 in Oklahoma gave the total number of the nation under Cherokee law to be 25,978. In 1900 there were 35,000 in Oklahoma. According to James Mooney (quoted by Frederick Webb Hodge) the majority of the earlier estimates of the Cherokee population are probably too low as the Cherokee occupied so extensive a territory that only a part of them came into contact with the Whites. Indian Affairs 1910 reported that in 1910 the Cherokee in Oklahoma contained 41,701 people, including 36,301 by blood, 286 by intermarriage and 4,917 Freedmen.[78] While the census of 1910 counted 31,489 Cherokees.

In the 2020 census a total of 1,130,730 people claimed Cherokee ancestry.[79] However the percentage of full-blood individuals is probably very low considering that the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians reported having only 395 full-blood members.[80] Perhaps there is a larger number of full-blood individuals among the United Keetoowah Band and among the Cherokee Nation.

Culture

[edit]Spirituality

[edit]The Cherokee believe that the world is divided into two major spiritual forces: "red" (war, success, youth) and "white" (peace, introspection, old age).[81][82][83]

Cultural institutions

[edit]The Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual, Inc., of Cherokee, North Carolina, is the oldest continuing Native American art co-operative. They were founded in 1946 to provide a venue for traditional Eastern Band Cherokee artists.[84] The Museum of the Cherokee People, also in Cherokee, displays permanent and changing exhibits, houses archives and collections important to Cherokee history, and sponsors cultural groups, such as the Warriors of the AniKituhwa dance group.[85]

In 2007, the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians entered into a partnership with Southwestern Community College and Western Carolina University to create the Oconaluftee Institute for Cultural Arts (OICA), to emphasize native art and culture in traditional fine arts education. This is intended both to preserve traditional art forms and encourage exploration of contemporary ideas. Located in Cherokee, OICA offered an associate degree program.[86] In August 2010, OICA acquired a letterpress and had the Cherokee syllabary recast to begin printing one-of-a-kind fine art books and prints in the Cherokee language.[87] In 2012, the Fine Art degree program at OICA was incorporated into Southwestern Community College and moved to the SCC Swain Center, where it continues to operate.[88]

The Cherokee Heritage Center, of Park Hill, Oklahoma, is the site of a reproduction of an ancient Cherokee village, Adams Rural Village (including 19th-century buildings), Nofire Farms, and the Cherokee Family Research Center for genealogy.[89] The Cherokee Heritage Center also houses the Cherokee National Archives. Both the Cherokee Nation (of Oklahoma) and the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee, as well as other tribes, contribute funding to the CHC.

Marriage

[edit]Before the 19th century, polygamy was common among the Cherokee, especially by elite men.[90] The matrilineal culture meant that women controlled property, such as their dwellings, and their children were considered born into their mother's clan, where they gained hereditary status. Advancement to leadership positions was generally subject to approval by the women elders. In addition, the society was matrifocal; customarily, a married couple lived with or near the woman's family, so she could be aided by her female relatives. Her eldest brother was a more important mentor to her sons than was their father, who belonged to another clan. Traditionally, couples, particularly women, can divorce freely.[91]

It was unusual for a Cherokee man to marry a European-American woman. The children of such a union were disadvantaged, as they would not belong to the nation. They would be born outside the clans and traditionally were not considered Cherokee citizens. This is because of the matrilineal aspect of Cherokee culture.[90] As the Cherokee began to adopt some elements of European-American culture in the early 19th century, they sent elite young men, such as John Ridge and Elias Boudinot to American schools for education. After Ridge had married a European-American woman from Connecticut and Boudinot was engaged to another, the Cherokee Council in 1825 passed a law making children of such unions full citizens of the tribe, as if their mothers were Cherokee. This was a way to protect the families of men expected to be leaders of the tribe.[92]

In the late nineteenth century, the U.S. government put new restrictions on marriage between a Cherokee and non-Cherokee, although it was still relatively common. A European-American man could legally marry a Cherokee woman by petitioning the federal court, after gaining the approval of ten of her blood relatives. Once married, the man had status as an "Intermarried White," a member of the Cherokee tribe with restricted rights; for instance, he could not hold any tribal office. He remained a citizen of and under the laws of the United States. Common law marriages were more popular. Such "Intermarried Whites" were listed in a separate category on the registers of the Dawes Rolls, prepared for allotment of plots of land to individual households of members of the tribe, in the early twentieth-century federal policy for assimilation of the Native Americans.

Ethnobotany definition

[edit]Ethnobotany is the study of interrelations between humans and plants; however, current use of the term implies the study of Indigenous or traditional knowledge of plants. It involves the Indigenous knowledge of plant classification, cultivation, and use as food, medicine and shelter.

Gender roles

[edit]Men and women have historically played important yet, at times, different roles in Cherokee society. Historically, women have primarily been the heads of households, owning the home and the land, farmers of the family's land, and "mothers" of the clans. As in many Native American cultures, Cherokee women are honored as life-givers.[93] As givers and nurturers of life via childbirth and the growing of plants, and community leaders as clan mothers, women are traditionally community leaders in Cherokee communities. Some have served as warriors, both historically and in contemporary culture in military service. Cherokee women are regarded as tradition-keepers and responsible for cultural preservation.[94]

The redefining of gender roles in Cherokee society first occurred in the time period between 1776 and 1835.[95] This period is demarcated by the De Soto exploration and subsequent invasion, was followed by the American Revolution in 1776, and culminated with the signing of Treaty of New Echota in 1835. The purpose of this redefinition was to push European social standards and norms on the Cherokee people.[95] The long-lasting effect of these practices reorganized Cherokee forms of government towards a male-dominated society which has affected the nation for generations.[96] Miles argues white agents were mainly responsible for the shifting of Cherokee attitudes toward women's role in politics and domestic spaces.[96] These "white agents" could be identified as white missionaries and white settlers seeking out "manifest destiny".[96] By the time of removal in the mid-1830s, Cherokee men and women had begun to fulfill different roles and expectations as defined by the "civilization" program promoted by US presidents Washington and Jefferson.[95]

While there is a record of a non-Native traveler in 1825 noticing what he considered to be "men who assumed the dress and performed the duties of women", this observer was unfamiliar with how the Natives in that region dressed. There is no evidence of what would now be considered "two-spirit" individuals in Cherokee society; this is generally the case in matriarchal and matrilineal cultures, as third gender roles are usually found in patriarchal societies and cultures with more rigid gender roles.[97]

Slavery

[edit]Slavery was a component of Cherokee society prior to European colonization, as they frequently enslaved enemy captives taken during times of conflict with other Indigenous tribes.[98] By their oral tradition, the Cherokee viewed slavery as the result of an individual's failure in warfare and as a temporary status, pending release or the slave's adoption into the tribe.[99] During the colonial era, Carolinian settlers purchased or impressed Cherokees as slaves during the late 17th and early 18th century.[100] The Cherokee were also among the Native American peoples who sold Indian slaves to traders for use as laborers in Virginia and further north. They took them as captives in raids on enemy tribes.[101]

As the Cherokee began to adopt some European-American customs, they began to purchase enslaved African Americans to serve as workers on their farms or plantations, which some of the elite families had in the antebellum years. When the Cherokee were forcibly removed on the Trail of Tears, they took slaves with them, and acquired others in Indian Territory.[102]

Funeral rites

[edit]Language and writing system

[edit]

The Cherokee speak a Southern Iroquoian language, which is polysynthetic and is written in a syllabary invented by Sequoyah (ᏍᏏᏉᏯ) in the 1810s.[103] For years, many people wrote and transliterated Cherokee or used poor intercompatible fonts to type out the syllabary. However, since the fairly recent addition of the Cherokee syllables to Unicode, the Cherokee language is experiencing a renaissance in its use on the Internet.

Because of the polysynthetic nature of the Cherokee language, new and descriptive words in Cherokee are easily constructed to reflect or express modern concepts. Examples include ditiyohihi (ᏗᏘᏲᎯᎯ), which means "he argues repeatedly and on purpose with a purpose," meaning "attorney." Another example is didaniyisgi (ᏗᏓᏂᏱᏍᎩ) which means "he catches them finally and conclusively," meaning "policeman."

Many words, however, have been borrowed from the English language, such as gasoline, which in Cherokee is ga-so-li-ne (ᎦᏐᎵᏁ). Many other words were borrowed from the languages of tribes who settled in Oklahoma in the early 20th century. One example relates to a town in Oklahoma named "Nowata". The word nowata is a Delaware Indian word for "welcome" (more precisely the Delaware word is nu-wi-ta which can mean "welcome" or "friend" in the Delaware Language). The white settlers of the area used the name "nowata" for the township, and local Cherokees, being unaware the word had its origins in the Delaware Language, called the town Amadikanigvnagvna (ᎠᎹᏗᎧᏂᎬᎾᎬᎾ) which means "the water is all gone from here", i.e. "no water".

Other examples of borrowed words are kawi (ᎧᏫ) for coffee and watsi (ᏩᏥ) for watch (which led to utana watsi (ᎤᏔᎾ ᏩᏥ) or "big watch" for clock).

The following table is an example of Cherokee text and its translation:

| ᏣᎳᎩ: ᏂᎦᏓ ᎠᏂᏴᏫ ᏂᎨᎫᏓᎸᎾ ᎠᎴ ᎤᏂᏠᏱ ᎤᎾᏕᎿ ᏚᏳᎧᏛ ᎨᏒᎢ. ᎨᏥᏁᎳ ᎤᎾᏓᏅᏖᏗ ᎠᎴ ᎤᏃᏟᏍᏗ ᎠᎴ ᏌᏊ ᎨᏒ ᏧᏂᎸᏫᏍᏓᏁᏗ ᎠᎾᏟᏅᏢ ᎠᏓᏅᏙ ᎬᏗ.[104] |

| Tsalagi: Nigada aniyvwi nigeguda'lvna ale unihloyi unadehna duyukdv gesv'i. Gejinela unadanvtehdi ale unohlisdi ale sagwu gesv junilvwisdanedi anahldinvdlv adanvdo gvhdi.[104] |

| All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood. (Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights)[104] |

Treaties and government

[edit]Treaties

[edit]The Cherokee have participated in at least thirty-six treaties in the past three hundred years.

Government

[edit]| 1794 | Establishment of the Cherokee National Council and officers over the whole nation |

| 1808 | Establishment of the Cherokee Lighthorse Guard, a national police force |

| 1809 | Establishment of the National Committee |

| 1810 | End of separate regional councils and abolition of blood vengeance |

| 1820 | Establishment of courts in eight districts to handle civil disputes |

| 1822 | Cherokee Supreme Court established |

| 1823 | National Committee given power to review acts of the National Council |

| 1827 | Constitution of the Cherokee Nation East |

| 1828 | Constitution of the Cherokee Nation West |

| 1832 | Suspension of elections in the Cherokee Nation East |

| 1839 | Constitution of the reunited Cherokee Nation |

| 1868 | Constitution of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians |

| 1888 | Charter of Incorporation issued by the State of North Carolina to the Eastern Band |

| 1950 | Constitution and federal charter of the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians |

| 1975 | Constitution of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma |

| 1999 | Constitution of the Cherokee Nation drafted[105] |

After being ravaged by smallpox, and feeling pressure from European settlers, the Cherokee adopted a European-American Representative democracy form of government in an effort to retain their lands. They established a governmental system modeled on that of the United States, with an elected principal chief, senate, and house of representatives. On April 10, 1810 the seven Cherokee clans met and began the abolition of blood vengeance by giving the sacred duty to the new Cherokee National government. Clans formally relinquished judicial responsibilities by the 1820s when the Cherokee Supreme Court was established. In 1825, the National Council extended citizenship to the children of Cherokee men married to white women. These ideas were largely incorporated into the 1827 Cherokee constitution.[106] The constitution stated that "No person who is of negro or mulatto [sic] parentage, either by the father or mother side, shall be eligible to hold any office of profit, honor or trust under this Government," with an exception for, "negroes and descendants of white and Indian men by negro women who may have been set free."[107] This definition to limit rights of multiracial descendants may have been more widely held among the elite than the general population.[108]

Modern Cherokee tribes

[edit]Cherokee Nation

[edit]

During 1898–1906 the federal government dissolved the former Cherokee Nation, to make way for the incorporation of Indian Territory into the new state of Oklahoma. From 1906 to 1975, the structure and function of the tribal government were defunct, except for the purposes of DOI management. In 1975 the tribe drafted a constitution, which they ratified on June 26, 1976,[109] and the tribe received federal recognition.

In 1999, the CN changed or added several provisions to its constitution, among them the designation of the tribe to be "Cherokee Nation," dropping "of Oklahoma." According to a 2009 statement by BIA head Larry Echo Hawk, the Cherokee Nation is not legally considered the "historical Cherokee tribe" but instead a "successor in interest." The attorney of the Cherokee Nation has stated that they intend to appeal this decision.[110]

The modern Cherokee Nation, in recent times, has expanded economically, providing equality and prosperity for its citizens. Under the leadership of Principal Chief Bill John Baker, the Nation has significant business, corporate, real estate, and agricultural interests. The CN controls Cherokee Nation Entertainment, Cherokee Nation Industries, and Cherokee Nation Businesses. CNI is a very large defense contractor that creates thousands of jobs in eastern Oklahoma for Cherokee citizens.

The CN has constructed health clinics throughout Oklahoma, contributed to community development programs, built roads and bridges, constructed learning facilities and universities for its citizens, instilled the practice of Gadugi and self-reliance, revitalized language immersion programs for its children and youth, and is a powerful and positive economic and political force in Eastern Oklahoma.

The CN hosts the Cherokee National Holiday on Labor Day weekend each year, and 80,000 to 90,000 Cherokee citizens travel to Tahlequah, Oklahoma, for the festivities. It publishes the Cherokee Phoenix, the tribal newspaper, in both English and Cherokee, using the Sequoyah syllabary. The Cherokee Nation council appropriates money for historic foundations concerned with the preservation of Cherokee culture.

The Cherokee Nation supports the Cherokee Nation Film festivals in Tahlequah, Oklahoma and participates in the Sundance Film Festival in Park City, Utah.

Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians

[edit]The Eastern Band of the Cherokee Indians in North Carolina, led by Chief Richard Sneed, hosts over a million visitors a year to cultural attractions of the 100-square-mile (260 km2) sovereign nation. The reservation, the "Qualla Boundary", has a population of over 8,000 Cherokee, primarily direct descendants of Indians who managed to avoid "The Trail of Tears".

Attractions include the Oconaluftee Indian Village, Museum of the Cherokee Indian, and the Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual. Founded in 1946, the Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual is the country's oldest and foremost Native American crafts cooperative.[111] The outdoor drama Unto These Hills, which debuted in 1950, recently broke record attendance sales. Together with Harrah's Cherokee Casino and Hotel, Cherokee Indian Hospital and Cherokee Boys Club, the tribe generated $78 million in the local economy in 2005.

United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians

[edit]

The United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians formed their government under the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 and gained federal recognition in 1946. Enrollment in the tribe is limited to people with a quarter or more of Cherokee blood. Many members of the UKB are descended from Old Settlers – Cherokees who moved to Arkansas and Indian Territory before the Trail of Tears.[112] Of the 12,000 people enrolled in the tribe, 11,000 live in Oklahoma. Their chief is Joe Bunch.

The UKB operate a tribal casino, bingo hall, smokeshop, fuel outlets, truck stop, and gallery that showcases art and crafts made by tribal members. The tribe issues their own tribal vehicle tags.[113]

Relations among the three federally recognized Cherokee tribes

[edit]The Cherokee Nation participates in numerous joint programs with the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians. It also participates in cultural exchange programs and joint Tribal Council meetings involving councilors from both Cherokee Tribes. These are held to address issues affecting all of the Cherokee people.

174 years after the Trail of Tears, on July 12, 2012, the leaders of the three separate Cherokee tribes met in North Carolina.[where?][114]

Contemporary settlement

[edit]Cherokee people are most concentrated in Oklahoma and North Carolina, but some reside in the US West Coast, due to economic migrations caused by the Dust Bowl during the Great Depression, job availability during the Second World War, and the Federal Indian Relocation program during the 1950s–1960s. Destinations for Cherokee diaspora included multi-ethnic/racial urban centers of California (i.e. the Greater Los Angeles and San Francisco Bay Areas). They frequently live in farming communities, or by military bases and other Indian reservations.[115]

Membership controversies

[edit]Tribal recognition and citizenship

[edit]The three Cherokee tribes have differing requirements for enrollment. The Cherokee Nation determines enrollment by lineal descent from Cherokees listed on the Dawes Rolls and has no minimum blood quantum requirement.[116] Currently, descendants of the Dawes Cherokee Freedman rolls are citizens of the tribe, pending court decisions. The Cherokee Nation includes numerous citizens who have mixed ancestry, including African-American, Latino American, Asian American, European-American, and others. The Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians requires a minimum of one-sixteenth Cherokee blood quantum (genealogical descent, equivalent to one great-great-grandparent) and an ancestor on the Baker Roll. The United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians requires a minimum of one-quarter Keetoowah Cherokee blood quantum (equivalent to one grandparent). The UKB does not allow citizens who have relinquished their citizenship to re-enroll in the UKB.[117]

The 2000 United States census reported 729,533 Americans self-identified as Cherokee. The 2010 census reported an increased number of 819,105 with almost 70% being mixed-race Cherokees. In 2015, the Cherokee Nation, the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians, and the Eastern Band of Cherokees had a combined enrolled population of roughly 344,700.[2]

Over 200 groups claim to be Cherokee nations, tribes, or bands.[118] Cherokee Nation spokesman Mike Miller has suggested that some groups, which he calls Cherokee Heritage Groups, are encouraged.[119] Others, however, are controversial for their attempts to gain economically through their claims to be Cherokee. The three federally recognized groups note that they are the only groups having the legal right to present themselves as Cherokee Indian Tribes and only their enrolled citizens are legally Cherokee.[120]

One exception to this may be the Texas Cherokee. Before 1975, they were considered part of the Cherokee Nation, as reflected in briefs filed before the Indian Claims Commission. At one time W.W. Keeler served as Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation and, at the same time, held the position as Chairman of the Texas Cherokee and Associated Bands (TCAB) Executive Committee. Following the adoption of the Cherokee constitution in 1976, TCAB descendants whose ancestors had remained a part of the physical Mount Tabor Community in Rusk County, Texas, were excluded from CN citizenship. Because they had already migrated from Indian Territory at the time of the Dawes Commission, their ancestors were not recorded on the Final Rolls of the Five Civilized Tribes, which serve as the basis for tracing descent for many individuals. But, most if not all TCAB descendants did have an ancestor listed on either the Guion-Miller or Old settler rolls.

While most Mount Tabor residents returned to the Cherokee Nation after the Civil War and following the death of John Ross in 1866, in the 21st century, there is a sizable group that is well documented but outside that body. It is not actively seeking a status clarification. They have treaty rights going back to the Treaty of Bird's Fort. From the end of the Civil War until 1975, they were associated with the Cherokee Nation.

Other remnant populations continue to exist throughout the Southeast United States and individually in the states surrounding Oklahoma. Many of these people trace descent from persons enumerated on official rolls such as the Guion-Miller, Drennan, Mullay, and Henderson Rolls, among others. Other descendants trace their heritage through the treaties of 1817 and 1819 with the federal government that gave individual land allotments to Cherokee households. State-recognized tribes may have different membership requirements and genealogical documentation than to the federally recognized ones.

Current enrollment guidelines of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma have been approved by the US Bureau of Indian Affairs. The CN noted such facts during the Constitutional Convention held to ratify a new governing document. The document was eventually ratified by a small portion of the electorate. Any changes to the tribe's enrollment procedures must be approved by the Department of Interior. Under 25 CFR 83, the Office of Federal Acknowledgment is required to first apply its own anthropological, genealogical, and historical research methods to any request for change by the tribe. It forwards its recommendations to the Assistant Secretary - Indian Affairs for consideration.[121]

Cherokee Freedmen

[edit]The Cherokee Freedmen, descendants of African American slaves owned by citizens of the Cherokee Nation during the Antebellum Period, were first guaranteed Cherokee citizenship under a treaty with the United States in 1866. This was in the wake of the American Civil War, when the U.S. emancipated slaves and passed US constitutional amendments granting freedmen citizenship in the United States.

In 1988, the federal court in the Freedmen case of Nero v. Cherokee Nation[122] held that Cherokees could decide citizenship requirements and exclude Freedmen. On March 7, 2006, the Cherokee Nation Judicial Appeal Tribunal ruled that the Cherokee Freedmen were eligible for Cherokee citizenship. This ruling proved controversial; while the Cherokee Freedman had historically been recorded as "citizens" of the Cherokee Nation at least since 1866 and the later Dawes Commission Land Rolls, the ruling "did not limit membership to people possessing Cherokee blood".[123] This ruling was consistent with the 1975 Constitution of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma, in its acceptance of the Cherokee Freedmen on the basis of historical citizenship, rather than documented blood relation.

On March 3, 2007, a constitutional amendment was passed by a Cherokee vote limiting citizenship to Cherokees on the Dawes Rolls for those listed as Cherokee by blood on the Dawes roll, which did not include partial Cherokee descendants of slaves, Shawnee and Delaware.[124] The Cherokee Freedmen had 90 days to appeal this amendment vote which disenfranchised them from Cherokee citizenship and file appeal within the Cherokee Nation Tribal Council, which is currently pending in Nash, et al. v. Cherokee Nation Registrar. On May 14, 2007, the Cherokee Freedmen were reinstated as citizens of the Cherokee Nation by the Cherokee Nation Tribal Courts through a temporary order and temporary injunction until the court reached its final decision.[125] On January 14, 2011, the tribal district court ruled that the 2007 constitutional amendment was invalid because it conflicted with the 1866 treaty guaranteeing the Freedmen's rights.[126]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "Pocket Pictorial". Archived April 6, 2010, at the Wayback Machine Oklahoma Indian Affairs Commission. 2010: 6 and 37. (retrieved June 11, 2010).

- ^ a b c Smithers, Gregory D. (October 1, 2015). "Why Do So Many Americans Think They Have Cherokee Blood?". www.slate.com. Retrieved April 24, 2017.

- ^ Chavez, Will (August 29, 2018). "Map shows CN citizen population for each state". Cherokee Phoenix. Tahlequah, OK. Retrieved September 4, 2020.

- ^ a b "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. 2014. Retrieved April 24, 2017.

Community Facts (Georgia), 2014 American Community Survey, Demographic and Housing Estimates (Age, Sex, Race, Households and Housing, ...)

- ^ http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/index.xhtml Archived 2015-01-08 at the Library of Congress Web Archives, American FactFinder, Community Facts (South Carolina), 2014 American Community Survey, Demographic and Housing Estimates (Age, Sex, Race, Households and Housing,...)

- ^ "Aboriginal Population Profile, 2019 Census". www12.statcan.gc.ca/. Statistics Canada. June 21, 2018. Retrieved December 31, 2021.

- ^ Sturtevant and Fogelson, 613

- ^ Jones, Daniel (2011). Roach, Peter; Setter, Jane; Esling, John (eds.). Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (18th ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-15255-6.

- ^ Wells, John C. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- ^ Stuyvesant, William C.; Fogelson, Raymond D., eds. (2004). Handbook of North American Indians: Southeast, Volume 14. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution. p. ix. ISBN 0-16-072300-0.

- ^ a b Mooney, James (2006) [1900]. Myths of the Cherokee and Sacred Formulas of the Cherokees. Kessinger Publishing. p. 393. ISBN 978-1-4286-4864-7.

- ^ Whyte, Thomas (June 2007). "Proto-Iroquoian divergence in the Late Archaic-Early Woodland period transition of the Appalachian highlands". Southeastern Archaeology. 26 (1): 134–144. JSTOR 40713422.

- ^ "Tribal Directory: Southeast". National Congress of American Indians. Retrieved June 9, 2017.

- ^ "The American Indian and Alaska Native Population: 2010" (PDF). Census 2010 Brief. February 1, 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 20, 2013. Retrieved January 29, 2013.

- ^ "Cherokee Indians". Encyclopedia of North Carolina. The University of North Carolina Press. Archived from the original on December 23, 2016. Retrieved June 3, 2014.

- ^ Buchanan, Heidi. "Research Guides: Cherokee Studies: Welcome". researchguides.wcu.edu. Retrieved April 2, 2024.

- ^ Staff REPORTS (August 22, 2023). "Native American remains receive symbolic headstone at Fort Campbell". cherokeephoenix.org. Retrieved April 2, 2024.

- ^ Nagle, Rebecca (November 5, 2019). "The U.S. has spent more money erasing Native languages than saving them". High Country News. Retrieved April 2, 2024.

- ^ "Cherokee: A Language of the United States". Ethnologue: Languages of the World. SIL International. 2013. Archived from the original on September 25, 2014. Retrieved October 20, 2014.

- ^ Charles A. Hanna, The Wilderness Trail, (New York: 1911). This was chronicled by de Soto's expedition as Chalaque.

- ^ Martin and Mauldin, A Dictionary of Creek/Muskogee, Sturtevant and Fogelson, p. 349.

- ^ Mooney, James (1975). Historical Sketch of the Cherokee. Chicago, IL: Aldine Pub. Co. p. 4. ISBN 0202011364.

- ^ "Cherokee" Archived April 25, 2019, at the Wayback Machine - Tolatsga.org

- ^ Boyle, John (August 21, 2017). "Answer Man: Did the Cherokee live on Biltmore Estate lands? Early settlers?". Asheville Citizen-Times. Retrieved August 21, 2017.

- ^ Sturtevant and Fogelson, 132

- ^ Finger, 6–7

- ^ Clark, Patricia Roberts (October 21, 2009). Tribal Names of the Americas: Spelling Variants and Alternative Forms, Cross-Referenced. McFarland. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-7864-5169-2.

- ^ Or Achalaque.[27]

- ^ Mooney

- ^ "Late Prehistoric/Early Historic Chiefdoms (ca. A.D. 1300-1850)" Archived October 4, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. New Georgia Encyclopedia. Retrieved July 22, 2010.

- ^ a b Mooney, James (1995) [1900]. Myths of the Cherokee. Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-28907-9.

- ^ Glottochronology from: Lounsbury, Floyd (1961), and Mithun, Marianne (1981), cited in Nicholas A. Hopkins, The Native Languages of the Southeastern United States.

- ^ Hally, David (2008). King: The Social Archaeology of a Late Mississippian Town in Northwestern Georgia. University of Alabama Press. p. 18. ISBN 9780817354602.

while men were considered to be dangerous immediately before and following their participation in warfare.

- ^ a b c Irwin 1992.

- ^ Mooney, p. 392.

- ^ Hamilton, Chuck (January 21, 2016). "Lost Nation of the Erie Part 1". www.chattanoogan.com. Archived from the original on January 23, 2017. Retrieved April 24, 2017.

- ^ Conley, A Cherokee Encyclopedia, p. 3

- ^ Mooney, Myths of the Cherokee p. 31.

- ^ Lewis Preston Summers, 1903, History of Southwest Virginia, 1746–1786, p. 40

- ^ Vicki Rozema, Footsteps of the Cherokees (1995), p. 14.

- ^ Oatis, Steven J. (2004). A Colonial Complex: South Carolina's Frontiers in the Era of the Yamasee War, 1680–1730. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-3575-5.

- ^ Brown, John P. "Eastern Cherokee Chiefs" Archived February 11, 2006, at the Wayback Machine, Chronicles of Oklahoma, Vol. 16, No. 1, March 1938. Retrieved September 21, 2009.

- ^ Adair, James (1775). The History of the American Indians. London: Dilly. p. 227. OCLC 444695506.

- ^ Timberlake, Henry (1765). "Memoirs of Henry Timberlake". London. pp. 49–51.

- ^ a b Rozema, pp. 17–23.

- ^ "Watauga Association" Archived November 13, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, North Carolina History Project. . Retrieved September 21, 2009.

- ^ Faragher, John Mack (1992). Daniel Boone: The Life and Legend of an American Pioneer. New York: Holt. pp. 93–4. ISBN 0-8050-1603-1.

- ^ Mooney, James. History, Myths, and Scared Formulas of the Cherokee, p. 83. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1900).

- ^ "New Georgia Encyclopedia: Chief Vann House". Georgiaencyclopedia.org. September 23, 2005. Archived from the original on October 21, 2012. Retrieved April 17, 2010.

- ^ "New Echota Historic Site". Ngeorgia.com. June 5, 2007. Archived from the original on April 24, 2010. Retrieved April 17, 2010.

- ^ "New Georgia Encyclopedia: Cherokee Phoenix". Georgiaencyclopedia.org. August 28, 2002. Archived from the original on May 12, 2013. Retrieved April 17, 2010.

- ^ Rollings (1992) pp. 187, 230–255.

- ^ Rollings (1992) pp. 187, 236.

- ^ Logan, Charles Russell. "The Promised Land: The Cherokees, Arkansas, and Removal, 1794–1839." Archived October 20, 2007, at the Wayback Machine Arkansas Historic Preservation Program. 1997 . Retrieved September 21, 2009.

- ^ Doublass (1912) pp. 40–2

- ^ Rollings (1992) p. 235.

- ^ Rollings (1992) pp. 239–40.

- ^ Rollings (1992) pp. 254–5, Doublass (1912) p. 44.

- ^ Rollings (1992) pp. 280–1

- ^ Treaties; Tennessee Encyclopedia, online; accessed October 2019

- ^ Wishart, p. 120

- ^ Wishart 1995.

- ^ "New Georgia Encyclopedia: "Worcester v. Georgia (1832)"". Georgiaencyclopedia.org. April 27, 2004. Archived from the original on September 18, 2008. Retrieved April 17, 2010.

- ^ "Treaty of New Echota, Dec. 29, 1835 (Cherokee – United States)". Ourgeorgiahistory.com. Archived from the original on October 27, 2009. Retrieved April 17, 2010.

- ^ "Cherokee in Georgia: Treaty of New Echota". Ngeorgia.com. June 5, 2007. Archived from the original on January 10, 2010. Retrieved April 17, 2010.

- ^ "What Happened on the Trail of Tears?". National Park Service. Archived from the original on October 12, 2020.

- ^ "Books by Alex W. Bealer". goodreads.com, 1972 and 1996. Retrieved March 27, 2011.