Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Wichita language

View on Wikipedia

| Wichita | |

|---|---|

| Kirikirʔi:s | |

| Native to | United States |

| Region | West-central Oklahoma |

| Ethnicity | Wichita, Tawakoni |

| Extinct | August 30, 2016, with the death of Doris McLemore[1] |

| Revival | Classes available |

Caddoan

| |

| Dialects |

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | wic |

| Glottolog | wich1260 |

| ELP | Wichita |

| Linguasphere | > 64-BAC-a 64-BAC > 64-BAC-a |

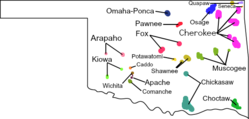

Distribution of Native American languages in Oklahoma | |

Wichita is a Caddoan language spoken in Anadarko, Oklahoma, by the Wichita and Affiliated Tribes. The last fluent heritage speaker, Doris Lamar-McLemore, died in 2016,[2] although in 2007 there were three first-language speakers alive.[3] This has rendered Wichita functionally extinct; however, the tribe offers classes to revitalize the language[4] and works in partnership with the Wichita Documentation Project of the University of Colorado, Boulder.[5]

Dialects

[edit]When the Europeans began to settle North America, Wichita separated into three dialects; Waco, Tawakoni, and Kirikirʔi꞉s (aka, Wichita Proper).[3] However, when the language was threatened and the number of speakers decreased, dialect differences largely disappeared.[6]

Status

[edit]As late as 2007 there were three living native speakers,[7] but the last known fluent native speaker, Doris Lamar-McLemore, died on 30 August 2016. This is a sharp decline from the 500 speakers estimated by Paul L. Garvin in 1950.[8]

Classification

[edit]Wichita is a member of the Caddoan language family, along with modern Caddo, Pawnee, Arikara, and Kitsai.[3]

Phonology

[edit]The phonology of Wichita is unusual, with no pure labial consonants (though there are two labiovelars /kʷ/ and /w/). There is only one nasal (depending on conflicting theory one or more nasal sounds may appear, but all theories seem to agree that they are allophones of the same phoneme, at best), and possibly a three vowel system using only height for contrast.[7]

Consonants

[edit]Wichita has 10 consonants. In the Americanist orthography generally used when describing Wichita, /t͡s/ is spelled ⟨c⟩, and /j/ is ⟨y⟩.

| Alveolar | Dorsal | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | labial. | |||

| Plosive | t | k | kʷ | ʔ |

| Affricate | t͡s | |||

| Fricative | s | h | ||

| Sonorant | ɾ ~ n | |||

| Semivowel | j | w | ||

Though neither Rood nor Garvin include nasals in their respective consonant charts for Wichita, Rood's later inclusion of nasals in phonetic transcription for his 2008 paper ("Some Wichita Recollections: Aspects of Culture Reflected in Language") support the appearance of at least /n/.[3]

- Labials are generally absent, occurring in only two roots: kammac to grind corn and camma:ci to hoe, to cultivate (⟨c⟩ = /t͡s/).

- Apart from the /m/ in these two verbs, nasals are allophonic. The allophones [ɾ] and [n] are in complementary distribution: It is [n] before alveolars (/t, t͡s, s/ and in geminate [nn]) and initially before a vowel, and [ɾ] elsewhere. Thus its initial consonant clusters are [n] and [ɾ̥h], and its medial and final clusters are [nt͡s], [nt], [ns], [nn], [ɾʔ], [ɾh].

- Final r and w are voiceless: [ɾ̥], [w̥]

- Glottalized final consonants: One aspect of Wichita phonetics is the occurrence of glottalized final consonants. Taylor asserts that when a long vowel precedes a glottal stop, there is no change to the pronunciation. However, when the glottal stop is preceded by a short vowel, the vowel is eliminated. If the short vowel was preceded by a consonant, then the consonant is glottalized. Taylor hypothesizes that these glottalized final consonants show that the consonant was not originally a final consonant, that the proto form (an earlier language from which Wichita split off, that Taylor was aiming to reconstruct in his paper) ended in a glottal stop, and that a vowel has been lost between the consonant and glottal stop.[6]

| Original word ending | Change | Result | Wichita example |

|---|---|---|---|

| [Vːʔ#] | No change | [Vːʔ#] | |

| [VːVʔ#] | -[V] | [Vːʔ#] | [hijaːʔ] (snow) |

| [CVʔ#] | -[V] | [Cʔ#] | [kiːsʔ] (bone) |

- Vː - long vowel

- V - short vowel

- C - consonant

- # - preceding sound ends word

- Taylor also finds that previous phonetic transcriptions have recorded the phoneme /t͡s/ (written ⟨c⟩), as occurring after /i/, while /s/ is recorded when preceded by /a/.[6]

- The *kʷ, *w, *p merger; or Why Wichita Has No /p/:

- In Wichita the sounds /kʷ/ and /w/ are not differentiated when they begin a word, and word-initial *p has become /w/. This is unusual, in that the majority of Caddoan languages pronounce words that used to begin with *w with /p/. In Wichita, the three sounds were also merged when preceded by a consonant. Wichita shifted consonant initial *p to /kʷ/ with other medial occurrences of *p. /kʷ/ and /w/ remain distinct following a vowel. For example, the word for 'man' is /wiːt͡s/ in Wichita, but /piːta/ in South Band Pawnee and /pita/ in Skiri Pawnee.[6]

Phonological rules

[edit]- The coalescence of morpheme-final /ɾ/ and subsequent morpheme-initial /t/ or /s/ to /t͡s/:

ti-r-tar-s

IND-PL-cut-IMPERF

→ ticac

'he cut them'

a:ra-r-tar

PERF-PL-cut

→ a:racar

'he has cut them'

a:ra-tar

PERF-cut

→ a:ratar

'he has cut it'

- /w/ changes to /kʷ/ whenever it follows a consonantal segment which is not /k/ or /kʷ/:

i-s-wa

IMP-you-go

→ iskwa

'go!'

i-t-wa

IMP-I-go

→ ickwa

'let me go!'

- /ɾ/ changes to /h/ before /k/ or /kʷ/. The most numerous examples involve the collective-plural prefix r- before a morpheme beginning with /k/:

ti-r-kita-re:sʔi

IND-COL-top-lie.INAN

→ tihkitare:sʔi

'they are lying on top'

- /t/ with a following /s/ or /ɾ/ to give /t͡s/:

keʔe-t-rika:s-ti:kwi

FUT-I-head-hit

→ keʔecika:sti:kwi

'I will hit him on the head'

- /t/ changes to /t͡s/ before /i/ or any non-vowel:

ta-t-r-taʔas

IND-I-COL-bite

→ taccaʔas

'I bit them'

- /k/ changes to /s/ before /t/:

ti-ʔak-tariyar-ic

IND-PL-cut.randomly-repeatedly

→ taʔastariyaric

'he butchered them'

- /ɾ/, /j/, and /h/ change to /s/ after /s/ or /t͡s/:

ichiris-ye:ckeʔe:kʔa

bird-ember

→ ichirisse:ckeʔe:kʔa

'redbird'

Vowels

[edit]Wichita has either three or four vowels, depending on analysis:[6][7][8]

| Front | Back | |

|---|---|---|

| High | ɪ ~ i ~ e | |

| Mid | ɛ ~ æ | (o/u) |

| Low | ɒ ~ a |

These are transcribed as ⟨i, e, a, o/u⟩.

Word-final vowels are devoiced.

Though Rood employs the letter ⟨o⟩ in his transcriptions,[3] Garvin instead uses ⟨u⟩, and asserts that /u/ is a separate phoneme.[8] However, considering the imprecision in vowel sound articulation, what is likely important about these transcriptions is that they attest to a back vowel that is not low.

Taylor uses Garvin's transcription in his analysis, but theorizes a shift of *u to /i/ medially in Wichita, but does not have enough examples to fully analyze all the possible environments. He also discusses a potential shift from *a to /i/, but again, does not have enough examples to develop a definitive hypothesis. Taylor finds /ɛ/ only occurs with intervocalic glottal stops.[6][8]

Rood argues that [o] is not phonemic, as it is often equivalent to any vowel + /w/ + any vowel. For example, /awa/ is frequently contracted to [óː] (the high tone is an effect of the elided consonant). There are relatively few cases where speakers will not accept a substitution of vowel + /w/ + vowel for [o]; one of them is [kóːs] 'eagle'.[clarification needed]

Rood also proposes that, with three vowels that are arguably high, mid, and low, the front-back distinction is not phonemic, and that one may therefore speak of a 'vertical' vowel inventory (see below). This also has been claimed for relatively few languages, such as the Northwest Caucasian languages and the Ndu languages of Papua New Guinea.

There is clearly at least a two-way contrast in vowel length. Rood proposes that there is a three-way contrast, which is quite rare among the world's languages, although well attested for Mixe, and probably present in Estonian. However, in Wichita, for each of the three to four vowels qualities, one of the three lengths is rare, and in addition the extra-long vowels frequently involve either an extra morpheme, or suggest that prosody may be at work. For example,

- nɪːt͡s.híːːʔɪh 'the strong one'

- nɪːːt͡s.híːːʔɪh 'the strong ones'

- hɛːhɪɾʔíːɾas 'let him find you'

- hɛːːhɪɾʔíːɾas 'let him find it for you'

- háɾah 'there'

- háːɾɪh 'here it is' (said when handing something over)

- háːːɾɪh 'that one'

(Note that it is common in many languages to use prosodic lengthening with demonstratives such as 'there' or 'that'.)[7]

This contrasts with Mixe, where it is easy to find a three-way length contrast without the addition of morphemes.[7]

Under Rood's analysis, then, Wichita has 9 phonemic vowels:[7]

| Short | Long | Overlong | |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | ɪ | ɪˑ | ɪː |

| Mid | ɛ | ɛˑ | ɛː |

| Low | a | aˑ | aː |

Tone

[edit]There is also a contrastive high tone, indicated here by an acute accent.

Syllable and phonotactics

[edit]While vowel sequences are uncommon (unless the extra-long vowels are considered sequences), consonant clusters are ubiquitous in Wichita. Words may begin with clusters such as [kskh] (kskhaːɾʔa) and [ɾ̥h] (ɾ̥hintsʔa). The longest cluster noted in Wichita is five consonants, counting [t͡s] as a single consonant: /nahiʔint͡skskih/ 'while sleeping'; however, Wichita syllables are more commonly CV or CVC.

Grammar and morphology

[edit]Wichita is an agglutinative, polysynthetic language, meaning words have a root verb basis to which information is added; that is, morphemes (affixes) are added to verb roots. These words may contain subjects, objects, indirect objects, and possibly indicate possession. Thus, surprisingly complex ideas can be communicated with as little as one word. For example, /kijaʔaːt͡ssthirʔaːt͡s/ means "one makes himself a fire".[3]

Nouns do not distinguish between singular and plural, as this information is specified as part of the verb. Wichita also does not distinguish between genders, which can be problematic for English language translation.[3]

Sentence structure is much more fluid than in English, with words being organized according to importance or novelty. Often the subject[clarification needed] of the sentence is placed initially. Linguist David S. Rood, who has written many papers concerning the Wichita language, recorded this example, as spoken by Bertha Provost (a native speaker, now deceased) in the late 1960s.[3]

hiɾaːwisʔihaːs

Old.time.people

kijariːt͡seːhiɾeːweʔe

God

hikaʔat͡saːkikaʔakʔit͡saki

When.he.made.us.dwell

hiɾaːɾʔ

Earth

tiʔi

This

naːkiɾih

Where.it.is.located

"When God put our ancestors on this earth."

The subject[clarification needed] of the sentence is ancestors, and thus the sentence begins with it, instead of God, or creation (when.he.made.us.dwell). This leads one to conclude Wichita has a largely free word-order, where parts of the sentence do not need to be located next to each other to be related.[3]

The perfective tense demonstrates that an act has been completed; on the other hand, the intentive tense indicates that a subject plans or planned to carry out a certain act. The habitual aspect indicates a habitual activity, for example: "he smokes" but not "he is smoking." Durative tense describes an activity, which is coextensive with something else.

Wichita has no indirect speech or passive voice. When using past tense, speakers must indicate if this knowledge of the past is based in hearsay or personal knowledge. Wichita has a clusivity distinction in the first person, i.e. separate ways of expressing "we" that explicitly includes or excludes the listener. Wichita also differentiates between singular, dual and plural number, instead of the simpler singular or plural designations commonly found.[3]

Affixes

[edit]Some Wichita affixes are:[9]

| Prefixes | |

|---|---|

| aorist | a ... ki-[clarification needed] |

| aorist quotative | aːʔa ... ki-[clarification needed] |

| future | keʔe- |

| future quotative | eheː- |

| perfect | aɾa- |

| perfect quotative | aːɾa- |

| indicative | ta/ti- |

| exclamatory | iskiri- |

| durative | a/i- |

| imperative | hi/i- |

| future imperative | kiʔi- |

| optative | kaʔa- |

| debetative | kaɾa- |

| Suffixes | |

|---|---|

| perfective | Ø |

| imperfective | -s |

| intentive | -staɾis |

| habitual | -ːss |

| too late | -iːhiːʔ |

- /ehèːʔáɾasis/

- imperfective.future.quotative

- 'I heard she'll be cooking it.'

Instrumental suffixes

[edit][10] The suffix is Rá:hir, added to the base. Another means of expressing instrument, used only for body parts, is a characteristic position of incorporation in the verb complex.

- ha:rhiwi:cá:hir 'using a bowl' (ha:rhiwi:c 'bowl')

- ika:rá:hir 'with a rock' (ika:ʔa 'rock')

- kirikirʔi:sá:hir 'in Wichita (the language)' (kirikirʔi:s 'Wichita)

- iskiʔo:rʔeh 'hold me in your arms' (iskiʔ 'imperative 2nd subject, 1st object'; a 'reflexive possessor'; ʔawir 'arm'; ʔahi 'hold').

- keʔese:cʔíriyari 'you will shake your head' (keʔes 'future 2nd subject'; a 'reflexive possessor'; ic 'face'; ʔiriyari 'go around'. Literally: 'you will go around, using your face').

Tense and aspect

[edit]One of these tense-aspect prefixes must occur in any complete verb form.[10]

| durative; directive | a / i |

| aorist (general past tense) | a...ki |

| perfect; recent past | ara |

| future quotative | eheː |

| subjunctive | ha...ki |

| exclamatory; immediate present | iskiri |

| ought | kara |

| optative | kaʔa |

| future | keʔe |

| future imperative | kiʔi |

| participle | na |

| interrogative indicative | ra |

| indicative | ta |

| negative indicative | ʔa |

Note: kara (ought), alone, always means 'subject should', but in complex constructions it is used for hypothetical action, as in 'what would you do if...')

The aspect-marking suffixes are:

| perfective | Ø |

| imperfective | s |

| intentive | staris |

| generic | ːss |

Other prefixes and suffixes are as follows:

- The exclamatory inflection indicates excitement.

- The imperative is used as the command form.

- The directive inflection is used in giving directions in sequences, such as describing how one makes something.

- This occurs only with 2nd or 3rd person subject pronouns and only in the singular.

- The optative is usually translated 'I wish' or 'subject should'.

- Although ought seems to imply that the action is the duty of the subject, it is frequently used for hypothetical statements in complex constructions.

- The unit durative suggests that the beginning and ending of the event are unimportant, or that the event is coextensive with something else.

- Indicative is the name of the most commonly used Wichita inflection translating English sentences out of context. It marks predication as a simple assertion. The time is always non-future, the event described is factual, and the situation is usually one of everyday conversation.

- The prefix is ti- with 3rd persons and ta- otherwise

- The aorist is used in narratives, stories, and in situations where something that happened or might have happened relatively far in the past is meant.

- The future may be interpreted in the traditional way. It is obligatory for any event in the future, no matter how imminent, unless the event is stated to be part of someone's plans, in which case intentive is used instead.

- The perfect implies recently completed.

- It makes the fact of completion of activity definite, and specifies an event in the recent past.

- The aorist intentive means 'I heard they were going to ... but they didn't.'

- The indicative intentive means 'They are going to ... ' without implying anything about the evidence on which the statement is based, nor about the probability of completion.

- The optional inflection quotative occurs with the aorist, future, or perfect tenses.

- If it occurs, it specifies that the speaker's information is from some source other than personal observation or knowledge.

- 'I heard that ... ' or 'I didn't know, but ... '

- If it does not occur, the form unambiguously implies that evidence for the report is personal observation.

- If it occurs, it specifies that the speaker's information is from some source other than personal observation or knowledge.

Examples: ʔarasi 'cook'

| á:kaʔarásis | quotative aorist imperfective | I heard she was cooking it |

| kiyakaʔarásis | quotative aorist imperfective | I heard she was cooking it |

| á:kaʔarásiki | quotative aorist perfective | I heard she was cooking it |

| á:kaʔarásistaris | quotative aorist intentive | I heard she was planning on cooking it |

| kiyakaʔarásistaris | quotative aorist intentive | I heard she was planning on cooking it |

| á:kaʔarásiki:ss | quotative aorist generic | I heard she always cooked it |

| kiyakaʔarásiki:ss | quotative aorist generic | I heard she always cooked it |

| ákaʔárasis | aorist imperfective | I know myself she was cooking it |

| ákaʔárasiki | aorist perfective | I know myself she cooked it |

| ákaʔarásistaris | aorist intentive | I know myself she was going to cook it |

| ákaʔaraásiki:ss | aorist generic | I know myself she always cooked it |

| keʔárasiki | future perfective | She will cook it |

| keʔárasis | future imperfective | She will be cooking it |

| keʔárasiki:ss | future generic | She will always cook it |

| ehéʔárasiki | quotative future perfective | I heard she will cook it |

| ehéʔárasis | quotative future imperfective | I heard she will be cooking it |

| eheʔárasiki:ss | quotative future generic | I heard she will always be the one to cook it |

| taʔarásis | indicative imperfective | She is cooking it; She cooked it |

| taʔarásistaris | indicative intentive | She's planning to cook it |

| taʔarásiki::s | indicative generic | She always cooks it |

| ískirá:rásis | exclamatory | There she goes, cooking it! |

| aʔarásis | directive imperfective | Then you cook it |

| haʔarásiki | imperative imperfective | Let her cook it |

| ki:ʔárasiki | future imperative perfective | Let her cook it later |

| ki:ʔárasiki:ss | future imperative generic | You must always let her cook it |

| á:raʔarásiki | quotative perfect perfective | I heard she cooked it |

| á:raʔarásistaris | quotative perfect intentive | I heard she was going to cook it |

| áraʔárasiki | perfect perfective | I know she cooked it |

| keʔeʔárasis | optative imperfective | I wish she'd be cooking it |

| keʔeʔárasiki | optative perfective | I wish she'd cook it |

| keʔeʔárasistaris | optative intentive | I wish she would plan to cook it |

| keʔeʔárasiki:ss | optative generic | I wish she'd always cook it |

| keʔeʔárasiki:hi:ʔ | optative too late | I wish she had cooked it |

| karaʔárasis | ought imperfective | She ought to be cooking it |

| karaʔarásiki:ss | ought generic | She should always cook it |

| karaʔárasiski:hiʔ | ought too late | She ought to have cooked it |

Modifiers

[edit]| assé:hah | all |

| ta:wʔic | few |

| tiʔih | this |

| ha:rí:h | that |

| hi:hánthirih | tomorrow |

| tiʔikhánthirisʔih | yesterday |

| chih á:kiʔí:rakhárisʔí:h | suddenly |

| ti:ʔ | at once |

| wah | already |

| chah | still |

| chih | continues |

| tiʔrih | here |

| harah | there |

| hí:raka:h | way off |

| hita | edge |

| kata | on the side |

| (i)wac | outside |

| ha | in water |

| ka | in a topless enclosure |

| ka: | in a completely enclosed space |

| kataska | in an open area |

| ʔir | in a direction |

| kataskeʔer | through the yard |

| kataskeʔero:c | out the other way from the yard |

Case

[edit][10] In the Wichita language, there are only case markings for obliques. Here are some examples:

Instrumental case

[edit]- The suffix Rá:hir, added to the base

- Another means of expressing instrument, used only for body parts, is a characteristic position of incorporation in the verb complex

- ha:rhiwi:cá:hir 'using a bowl' (ha:rhiwi:c 'bowl')

- ika:rá:hir 'with a rock' (ika:ʔa 'rock')

Locative case

[edit]Most nouns take a locative suffix kiyah:

ika:ʔa

rock

-kiyah

LOC

'where the rock is'

But a few take the verbal -hirih:

hir-ahrʔa

ground

-hirih

LOC

'on the ground'

Any verbal participle (i.e. any sentence) can be converted to a locative clause by the suffix -hirih

- tihe:ha 'it is a creek'

- nahe:hárih 'where the creek is'

Predicates and arguments

[edit]Wichita is a polysynthetic language. Almost all the information in any simple sentence is expressed by means of bound morphemes in the verb complex. The only exception to this are (1) noun stems, specifically those functioning as agents of transitive verbs but sometimes those in other functions as well, and (2) specific modifying particles. A typical sentence from a story is the following:[11]

wa:cʔarʔa

squirrel

kiya+

QUOT

a...ki+

AOR

a+

PVB

Riwa:c+

big (quantity)

ʔaras+

meat

Ra+

COL

ri+

PORT

kita+

top

ʔa+

come

hi:riks+

REP

s

IPFV

na+

PTCP

ya:k+

wood

r+

COL

wi+

be upright

hrih

LOC

'The squirrel, by making many trips, carried the large quantity of meat up into the top of the tree, they say.'

Note that squirrel is the agent and occurs by itself with no morphemes indicating number or anything else. The verb, in addition to the verbal units of quotative, aorist, repetitive, and imperfective, also contain morphemes that indicate the agent is singular, the patient is collective, the direction of the action is to the top, and all the lexical information about the whole patient noun phrase, "big quantity of meat."

Gender

[edit]In the Wichita language, there is no gender distinction (WALS).

Person and possession

[edit]| Subjective | Objective | |

|---|---|---|

| 1st person | -t- | -ki- |

| 2nd person | -s- | -a:- |

| 3rd person | -i- | Ø |

| inclusive | -ciy- | -ca:ki- |

The verb 'have, possess' in Wichita is /uR ... ʔi/, a combination of the preverb 'possessive' and the root 'be'. Possession of a noun can be expressed by incorporating that noun in this verb and indicating the person of the possessor by the subject pronoun:[12][13]

na-

PTCP

t-

1.SBJ

uR-

POSS

ʔak-

wife

ʔi-

be

h

SUBORD

'my wife'

niye:s

child

na-

PTCP

t-

1.SBJ-

uR-

POSS

ʔiki-

be.PL

h

SUBORD

'my children'

Number marking

[edit]Nouns can be divided into those that are countable and those that are not. In general, this correlates with the possibility for plural marking: Countable nouns can be marked for dual or plural; if not so marked, they are assumed to be singular. Uncountable nouns cannot be pluralized.

Those uncountable nouns that are also liquids are marked as such by a special morpheme, kir.

ta

IND

i

3.SBJ

a:

PVB

ti:sa:s

medicine

kir

liquid

ri

PORT

ʔa

come

s

IPFV

'He is bringing (liquid) medicine'

Those incountable nouns that are not liquid are not otherwise marked in Wichita. This feature is labeled dry mass. Forms such as ye:c 'fire', kirʔi:c 'bread', and ka:hi:c 'salt' are included in this category.

ta

IND

i

3.SBJ

a:

PVB

ya:c

fire

ri

PORT

ʔa

come

s

IPFV

'He is bringing fire.'

ta

IND

i

3.SBJ

a:

PVB

ka:hi:c

salt

ri

PORT

ʔa

come

s

IPFV

'He is bringing salt.'

Wichita countable nouns are divided into those that are collective and those that are not. The collective category includes most materials, such as wood; anything that normally comes in pieces, such as meat, corn, or flour; and any containers such as pots, bowls, or sacks when they are filled with pieces of something.

ta

IND

i

3.SBJ

a:

PVB

aʔas

meat

ra

COL

ri

PORT

ʔa

come

s

IPFV

'He is bringing meat.'

ta

IND

i

3.SBJ

a:

PVB

aʔas

meat

ri

PORT

ʔa

come

s

IPFV

'He is bringing (one piece of) meat.'

Some of the noncollective nominals are also marked for other selectional restrictions. In particular, with some verbs, animate nouns (including first and second person pronouns) require special treatment when they are patients in the sentence. Whenever there is an animate patient or object of certain verbs such as u...raʔa 'bring' or irasi 'find', the morpheme |hiʔri|(/hirʔ/, /hiʔr/, /hirʔi/) also occurs with the verb. The use of this morpheme is not predictable by rule and must be specified for each verb in the language that requires it.

ta

IND

i

3.SBJ

irasi

find

s

IPFV

'He found it (inanimate).'

ta

IND

i

3.SBJ

hirʔi

patient is animate

irasi

find

s

IPFV

'He found it (animate).'

Like hiʔri 'patient is animate', the morpheme wakhahr, means 'patient is an activity'.

Countable nouns that are neither animate nor activities, such as chairs, apples, rocks, or body parts, do not require any semantic class agreement morphemes in the surface grammar of Wichita.

The morpheme |ra:k| marks any or all non-third persons in the sentence as plural.

The morpheme for 'collective' or 'patient is not singular'. The shape of this varies from verb to verb, but the collective is usually |ru|, |ra|, or |r|.

The noncollective plural is usually |ʔak|. Instead of a morpheme here, some roots change form to mark plural. Examples include:

| Word | Singular | Plural |

|---|---|---|

| cook | ʔarasi | wa:rasʔi:rʔ |

| eat | kaʔac | ʔa |

| kill | ki | ʔessa |

A surface structure object in the non-third-person category can be clearly marked as singular, dual, or plural. The morpheme ra:k marks plurality; a combination oh hi and ʔak marks dual. Singular is marked by zero.

If both agent and patient are third person, a few intransitive verbs permit the same distinctions for patients as are possible for non-third objects: singular, dual, and plural. These verbs (such as 'come' and 'sit') allow the morpheme wa to mark 'dual patient'. In all other cases the morphemes ru, ra, r, or ʔak means 'patient is plural'.

- |hi| subject is nonsingular

- |ʔak| third person patient is nonsingular

- |ra:k| non-third-person is plural. If both the subject and object are non-third person, reference is to the object only.

- |hi ... ʔak| non-third-person is dual

- |ra:kʔak| combine meanings of ra:k and ʔak

- zero singular[13]

Endangerment

[edit]According to the Ethnologue Languages of the World website, the Wichita language is "dormant", meaning that no one has more than symbolic proficiency.[14] The last native speaker of the Wichita language, Doris Jean Lamar McLemore, died in 2016. The reason for the language's decline is because the speakers of the Wichita language switched to speaking English. Thus, children were not being taught Wichita and only the elders knew the language. "Extensive efforts to document and preserve the language" are in effect through the Wichita Documentation Project.

Revitalization efforts

[edit]The Wichita and Affiliated Tribes offered language classes, taught by Doris McLemore and Shirley Davilla.[4] The tribe created an immersion class for children and a class for adults. Linguist David Rood has collaborated with Wichita speakers to create a dictionary and language CDs.[15] The tribe is collaborating with Rood of the University of Colorado, Boulder to document and teach the language through the Wichita Documentation Project.[5]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Poolaw, Rhiannon (August 31, 2016). "Last Wichita Speaker Passes Away". ABC News 7. KSWO. Retrieved September 1, 2016.

- ^ McLemore, Doris (January 30, 2008). "The Last Living Speaker of Wichita". The Bryant Park Project (Interview). Interviewed by Stewart, Alison. NPR.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Rood 2008, pp. 395–405

- ^ a b Wichita Language Class. Archived 2010-07-02 at the Wayback Machine Wichita and Affiliated Tribes. 18 Feb 2009 (retrieved 14 Nov 2019)

- ^ a b "Wichita: About the Project." Archived 2011-11-16 at the Wayback Machine Department of Linguistics, University of Colorado, Boulder. (retrieved 17 July 2010)

- ^ a b c d e f Taylor 1963.

- ^ a b c d e f g Rood 1975

- ^ a b c d Garvin 1950

- ^ "Sketch of Wichita, a Caddoan Language" (PDF). colorado.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 16, 2011.

- ^ a b c Rood 1976

- ^ a b "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 23, 2015. Retrieved February 22, 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Rood, David S. "Agent and object in Wichita." Lingua 28 (1971-1972): 100. Web. 14 Feb. 2014

- ^ a b Rood 1996.

- ^ "Wichita". Ethnologue. Retrieved January 29, 2020.

- ^ Ruckman, S. E. "Tribal language fading away." Tulsa World. 26 Nov 2007 (retrieved 3 Oct 2009)

References

[edit]- Garvin, Paul L. (1950). "Wichita I: Phonemics". International Journal of American Linguistics. 16 (4): 179–184. doi:10.1086/464086. S2CID 143828845.

- Rood, David S. (1975). "The Implications of Wichita Phonology". Language. 51 (2): 315–337. doi:10.2307/412858. JSTOR 412858.

- Rood, David S. (1976). Wichita grammar. New York: Garland. ISBN 978-0-8240-1972-3.

- Rood, David S. (2008). "Some Wichita Recollections: Aspects of Culture Reflected in Language". Plains Anthropologist. 53 (208): 395–405. doi:10.1179/pan.2008.029. S2CID 143889526.

- Taylor, Allan R. (1963). "Comparative Caddoan". International Journal of American Linguistics. 29 (2): 113–131. doi:10.1086/464725. S2CID 224809647.

Further reading

[edit]- Marcy. (1853). (pp. 307–308).

- Rood, David S. (1971a). "Agent and object in Wichita". Lingua. 28: 100–107. doi:10.1016/0024-3841(71)90050-7.

- Rood, David S. (1971b). "Wichita: An unusual phonology system". Colorado Research in Linguistics. 1: R1 – R24. doi:10.25810/a3tf-4246.

- Rood, David S. (1973). "Aspects of subordination in Lakhota and Wichita". In Corum, Claudia; Smith-Stark, T. Cedric; Weiser, Ann (eds.). You Take the High Node and I'll Take the Low Node: Papers from the Comparative Syntax Festival, the Differences between Main and Subordinate Clauses. Chicago: Chicago Linguistics Society. pp. 71–88. LCCN 73085640.

- Rood, David S. (1975b). "Wichita verb structure: Inflectional categories". In Crawford, James M. (ed.). Studies in Southeastern Indian Languages. Athens: University of Georgia Press. pp. 121–134. ISBN 978-0-8203-0334-5.

- Rood, David S. (1996). "Sketch of Wichita, a Caddoan language". Handbook of North American Indians. Vol. 17. pp. 580–608.

- Rood, David S. (1998). "'To be' in Wichita". In Hinton, Leanne; Munro, Pamela (eds.). Studies in American Indian Languages: Description and Theory. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 190–196. ISBN 978-0-520-09789-6. LCCN 98023535.

- Rood, David S. (2015) [1977]. "Wichita texts". International Journal of American Linguistics. Native American Texts Series. 2 (1): 91–128. ISBN 9780226343914.

- Schmitt. (1950).

- Schmitt, Karl; Schmitt, Iva Ósanai (1952). Wichita kinship past and present. Norman, OK: University Book Exchange. LCCN 54000195.

- Schoolcraft, Henry. (1851–1857). Historical and statistical information respecting the history, condition, and prospects of the Indian tribes of the US. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo.

- Schoolcraft, Henry. (1953). (pp. 709–711).

- Spier, Leslie (1924). "Wichita and Caddo relationship terms". American Anthropologist. 26 (2): 258–263. doi:10.1525/aa.1924.26.2.02a00080.

- Vincent, Nigel (1978). "A note on natural classes and the Wichita consonant system". International Journal of American Linguistics. 44 (3): 230–232. doi:10.1086/465549. S2CID 145000151.

- Whipple (1856). Reports of explorations and surveys to ascertain the most practicable and economic route for a railroad from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean (Report). Washington: War Department. pp. 65–68. (Information on the Waco dialect)

External links

[edit]- Sketch of Wichita, a Caddoan language

- Wichita and Affiliated Tribes Language Class, with sample vocabulary

- Wichita Language Documentation Project Archived 2011-06-06 at the Wayback Machine

- Wichita Indian Language (Witchita)

- Slideshow of Doris Jean Lamar McLemore telling the Wichita creation story in Wichita

- Exploration of the Red River of Louisiana, in the year 1852 / by Randolph B. Marcy; assisted by George B. McClellan. hosted by the Portal to Texas History. See Appendix H, which compares the English, Comanche, and Wichita languages.

Wichita language

View on GrokipediaClassification and Dialects

Classification

The Wichita language belongs to the Caddoan language family, a small group of Native American languages historically spoken across the Great Plains region of the United States.[1] Within this family, Wichita is classified in the Northern Caddoan branch, alongside Pawnee (including its dialects Skiri and South Band), Arikara, and the now-extinct Kitsai.[9][10] This branch is distinguished from the Southern Caddoan branch, which consists primarily of Caddo and its dialects, with the two branches diverging approximately 3,500 years ago based on glottochronological estimates.[9] The classification reflects a deep-time separation, rendering mutual intelligibility between Northern and Southern languages negligible.[10] Historical comparisons place Wichita as an early offshoot from Proto-Northern-Caddoan, predating the splits that led to Kitsai and the Pawnee-Arikara subgroup.[9] Impressionistic time depths suggest that Wichita and Pawnee diverged around 1,200–1,500 years ago, while Wichita and Kitsai share a similar divergence timeframe.[10] Proposed reconstructions of Proto-Caddoan, developed collaboratively by linguists including Wallace Chafe, Douglas R. Parks, and David S. Rood, provide a framework for understanding these relations, positing a proto-sound system with three vowel qualities (/i, a, u/) and a range of consonants that evolved differently across branches.[10][11] For instance, Wichita retains certain Proto-Caddoan features in its pitch accent system, which it shares more closely with Caddo than with other Northern languages, though overall phonological innovations align it with Pawnee.[12] Evidence supporting Wichita's classification draws from lexical, phonological, and grammatical correspondences. Lexically, Northern Caddoan languages exhibit significant cognate retention; for example, Pawnee and Kitsai share about 60% cognates in basic vocabulary, with Wichita showing comparable overlap in core terms reconstructed to Proto-Northern-Caddoan, such as those for body parts and numerals.[10] Phonologically, shared innovations include complex consonantal clusters (up to three or four elements) in Wichita and Pawnee, alongside regular sound correspondences like the reduction of intervocalic clusters observed across the branch.[12][10] Grammatically, all Northern Caddoan languages are polysynthetic, featuring verb-complexes with extensive bound morphology for arguments, tense, and evidentiality; Wichita and Pawnee, in particular, share locative verb stem formations and instrumental prefixes traceable to Proto-Caddoan.[11] These features contrast with Southern Caddoan's more conservative retention of certain proto-forms but divergent verb ordering and affixation patterns.[9]Dialects

The Wichita language historically encompassed three main dialects corresponding to specific bands within the tribe: Waco (Wakʔu), Tawakoni (Tawakʔu), and Kirikirʔi:s, the latter serving as the prestige variety also known as Wichita Proper.[13] These dialects were mutually intelligible but displayed minor phonological and lexical variations, including differences in initial consonants and certain vocabulary items reflective of geographic separation among the bands.[10] In the 19th century, extensive population movements—driven by conflicts, disease, and forced relocations—along with increased intermarriage among the bands, accelerated dialect leveling as the Wichita and affiliated groups consolidated on reservations in Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) following their removal from Texas and Kansas around 1859–1867.[14] This convergence homogenized speech patterns, eliminating distinct dialectal features by the early 20th century. Linguistic evidence from early 20th-century tribal histories and mid-20th-century recordings, such as those collected by anthropologist James Mooney in the 1890s and linguist David S. Rood starting in the 1960s, confirms the disappearance of dialectal distinctions, with all remaining speakers employing a single, undifferentiated variety of Wichita by the 1990s.[10][13]Sociolinguistic Status

Speaker Population and Vitality

The Wichita language experienced a significant decline in speaker numbers throughout the 20th century, with only a handful of fluent and semi-speakers remaining by the early 2000s, reflecting the rapid loss of fluent transmission across generations.[1] The death of Doris Lamar-McLemore, the last fluent speaker, on August 30, 2016, marked a critical turning point, leading to the language's official declaration as dormant by linguistic authorities.[15][16] McLemore had collaborated extensively with linguists to document the language in her later years, but her passing ended active first-language use.[17] As of 2025, the Wichita language has no fluent speakers, placing it in a dormant status with no L1 users reported.[5] However, passive knowledge persists among some tribal elders, enabling limited comprehension and ceremonial application in cultural settings.[1] The Wichita and Affiliated Tribes, with an enrolled membership of 3,879 as of 2025, represent a modest community base that constrains broader revitalization and intergenerational transmission efforts.[18]Endangerment Factors

The decline of the Wichita language was profoundly influenced by 19th-century forced relocations that disrupted traditional community structures and language transmission. In 1863, Confederate forces compelled the Wichita people to abandon their lands in Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) and flee northward to Kansas, where they endured severe hardships including starvation, smallpox, and cholera outbreaks, reducing their population from over 1,400 to 822 by 1867. This displacement severed ties to ancestral territories and communal practices essential for daily language use. Subsequently, in 1867, the U.S. government relocated the tribe back to a reservation in southwestern Oklahoma, further fragmenting social networks and exposing them to ongoing settler encroachment, which eroded the monolingual environments necessary for sustaining the language.[14] Assimilation policies, particularly through federal boarding schools from the late 19th to mid-20th centuries, accelerated language loss by enforcing English-only environments and punishing indigenous language use. Wichita children were compelled to attend institutions such as the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, where they were isolated from family, stripped of cultural attire, and subjected to rigorous English immersion to "civilize" them, effectively halting intergenerational transmission within a generation. These schools, operational across the U.S. including in Oklahoma, aimed to eradicate Native languages as part of broader efforts to integrate tribes into Anglo-American society, resulting in widespread attrition of fluent speakers among the Wichita.[19][20] Post-1950s economic and social pressures intensified the shift to English, breaking down intergenerational transmission as families prioritized integration for employment and education opportunities. With the termination of federal restrictions on tribal mobility and the rise of urban job markets, many Wichita individuals adopted English as the primary language for socioeconomic advancement, leading to fewer opportunities for children to acquire Wichita fluently at home. By the late 20th century, this linguistic shift had rendered the language dormant, with no remaining first-language speakers.[5][20] Urbanization and intermarriage further diminished monolingual Wichita-speaking communities by the 2000s, as tribal members migrated to cities like Oklahoma City and Anadarko for work, diluting daily language practice within extended families. Intermarriage with non-Wichita speakers, common in reservation and urban settings, reduced the pool of native models for language acquisition, exacerbating the decline in household transmission and contributing to the absence of fluent elders by the early 21st century.[20]Phonology

Consonants

The Wichita language features a small consonant inventory of 9 phonemes, notable for the systematic absence of native labial consonants other than the glide /w/. The stops are voiceless and unaspirated (/t/, /k/), the affricate is alveolar (/ts/), and fricatives include /s/ and /h/; additionally, there is a glottal stop /ʔ/ and glides /w/ and /j/. A distinctive alveolar sonorant /r/ functions primarily as a flap [ɾ] or tap, exhibiting nasal allophones in specific environments, such as before alveolar consonants or in geminate form, and voiceless variants [ɾ̥] or [n̥] word-initially. Complex stops like glottalized /kʔ/ and labio-velar /kʷ/ occur in clusters.[21][22]| Phoneme | Orthography (Practical System) | Articulatory Description | Example Word (with Gloss) |

|---|---|---|---|

| /t/ | t | Voiceless alveolar stop | /tá·ra·h/ 'close' |

| /k/ | k | Voiceless velar stop | /kha·ts/ 'white' |

| /ts/ | c | Voiceless alveolar affricate | /tsʰe:tsʔa/ 'dawn' |

| /s/ | s | Voiceless alveolar fricative | /sa·k/ 'foot' |

| /h/ | h | Voiceless glottal fricative | /ha·kí·tʃ/ 'singing' |

| /ʔ/ | ’ | Glottal stop | /niʔ·ki/ 'child' |

| /w/ | w | Labialized velar glide | /wa·kʰ/ 'woman' |

| /j/ | y | Palatal glide | /ya·k/ 'to go' |

| /r/ | r (or n in some notations for nasal allophone) | Alveolar flap/tap, with allophones [ɾ, n, ɾ̥, n̥] | /niʔ·ki/ 'child'; intervocalic [ɾ] in /ta·r·a/ 'arrive' |