Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Web crawler

View on Wikipedia

A web crawler, sometimes called a spider or spiderbot and often shortened to crawler, is an Internet bot that systematically browses the World Wide Web and that is typically operated by search engines for the purpose of Web indexing (web spidering).[1]

Web search engines and some other websites use Web crawling or spidering software to update their web content or indices of other sites' web content. Web crawlers copy pages for processing by a search engine, which indexes the downloaded pages so that users can search more efficiently.

Crawlers consume resources on visited systems and often visit sites unprompted. Issues of schedule, load, and "politeness" come into play when large collections of pages are accessed. Mechanisms exist for public sites not wishing to be crawled to make this known to the crawling agent. For example, including a robots.txt file can request bots to index only parts of a website, or nothing at all.

The number of Internet pages is extremely large; even the largest crawlers fall short of making a complete index. For this reason, search engines struggled to give relevant search results in the early years of the World Wide Web, before 2000. Today, relevant results are given almost instantly.

Crawlers can validate hyperlinks and HTML code. They can also be used for web scraping and data-driven programming.

Nomenclature

[edit]A web crawler is also known as a spider,[2] an ant, an automatic indexer,[3] or (in the FOAF software context) a Web scutter.[4]

Overview

[edit]A Web crawler starts with a list of URLs to visit. Those first URLs are called the seeds. As the crawler visits these URLs, by communicating with web servers that respond to those URLs, it identifies all the hyperlinks in the retrieved web pages and adds them to the list of URLs to visit, called the crawl frontier. URLs from the frontier are recursively visited according to a set of policies. If the crawler is performing archiving of websites (or web archiving), it copies and saves the information as it goes. The archives are usually stored in such a way they can be viewed, read and navigated as if they were on the live web, but are preserved as 'snapshots'.[5]

The archive is known as the repository and is designed to store and manage the collection of web pages. The repository only stores HTML pages and these pages are stored as distinct files. A repository is similar to any other system that stores data, like a modern-day database. The only difference is that a repository does not need all the functionality offered by a database system. The repository stores the most recent version of the web page retrieved by the crawler.[citation needed]

The large volume implies the crawler can only download a limited number of the Web pages within a given time, so it needs to prioritize its downloads. The high rate of change can imply the pages might have already been updated or even deleted.

The number of possible URLs crawled being generated by server-side software has also made it difficult for web crawlers to avoid retrieving duplicate content. Endless combinations of HTTP GET (URL-based) parameters exist, of which only a small selection will actually return unique content. For example, a simple online photo gallery may offer three options to users, as specified through HTTP GET parameters in the URL. If there exist four ways to sort images, three choices of thumbnail size, two file formats, and an option to disable user-provided content, then the same set of content can be accessed with 48 different URLs, all of which may be linked on the site. This mathematical combination creates a problem for crawlers, as they must sort through endless combinations of relatively minor scripted changes in order to retrieve unique content.

As Edwards et al. noted, "Given that the bandwidth for conducting crawls is neither infinite nor free, it is becoming essential to crawl the Web in not only a scalable, but efficient way, if some reasonable measure of quality or freshness is to be maintained."[6] A crawler must carefully choose at each step which pages to visit next.

Crawling policy

[edit]The behavior of a Web crawler is the outcome of a combination of policies:[7]

- a selection policy which states the pages to download,

- a re-visit policy which states when to check for changes to the pages,

- a politeness policy that states how to avoid overloading websites.

- a parallelization policy that states how to coordinate distributed web crawlers.

Selection policy

[edit]Given the current size of the Web, even large search engines cover only a portion of the publicly available part. A 2009 study showed even large-scale search engines index no more than 40–70% of the indexable Web;[8] a previous study by Steve Lawrence and Lee Giles showed that no search engine indexed more than 16% of the Web in 1999.[9] As a crawler always downloads just a fraction of the Web pages, it is highly desirable for the downloaded fraction to contain the most relevant pages and not just a random sample of the Web.

This requires a metric of importance for prioritizing Web pages. The importance of a page is a function of its intrinsic quality, its popularity in terms of links or visits, and even of its URL (the latter is the case of vertical search engines restricted to a single top-level domain, or search engines restricted to a fixed Web site). Designing a good selection policy has an added difficulty: it must work with partial information, as the complete set of Web pages is not known during crawling.

In addition to prioritizing which pages to crawl, web crawlers also take into account directives that influence how content is indexed or linked. Meta tags such as noindex and nofollow inform compliant crawlers not to include a page in their search index or not to follow links on that page, respectively. These directives allow website operators to manage which pages appear in search results and help control the transmission of ranking signals.[10][11]

Junghoo Cho et al. made the first study on policies for crawling scheduling. Their data set was a 180,000-pages crawl from the stanford.edu domain, in which a crawling simulation was done with different strategies.[12] The ordering metrics tested were breadth-first, backlink count and partial PageRank calculations. One of the conclusions was that if the crawler wants to download pages with high Pagerank early during the crawling process, then the partial Pagerank strategy is the better, followed by breadth-first and backlink-count. However, these results are for just a single domain. Cho also wrote his PhD dissertation at Stanford on web crawling.[13]

Najork and Wiener performed an actual crawl on 328 million pages, using breadth-first ordering.[14] They found that a breadth-first crawl captures pages with high Pagerank early in the crawl (but they did not compare this strategy against other strategies). The explanation given by the authors for this result is that "the most important pages have many links to them from numerous hosts, and those links will be found early, regardless of on which host or page the crawl originates."

Abiteboul designed a crawling strategy based on an algorithm called OPIC (On-line Page Importance Computation).[15] In OPIC, each page is given an initial sum of "cash" that is distributed equally among the pages it points to. It is similar to a PageRank computation, but it is faster and is only done in one step. An OPIC-driven crawler downloads first the pages in the crawling frontier with higher amounts of "cash". Experiments were carried in a 100,000-pages synthetic graph with a power-law distribution of in-links. However, there was no comparison with other strategies nor experiments in the real Web.

Boldi et al. used simulation on subsets of the Web of 40 million pages from the .it domain and 100 million pages from the WebBase crawl, testing breadth-first against depth-first, random ordering and an omniscient strategy. The comparison was based on how well PageRank computed on a partial crawl approximates the true PageRank value. Some visits that accumulate PageRank very quickly (most notably, breadth-first and the omniscient visit) provide very poor progressive approximations.[16][17]

Baeza-Yates et al. used simulation on two subsets of the Web of 3 million pages from the .gr and .cl domain, testing several crawling strategies.[18] They showed that both the OPIC strategy and a strategy that uses the length of the per-site queues are better than breadth-first crawling, and that it is also very effective to use a previous crawl, when it is available, to guide the current one.

Daneshpajouh et al. designed a community based algorithm for discovering good seeds.[19] Their method crawls web pages with high PageRank from different communities in less iteration in comparison with crawl starting from random seeds. One can extract good seed from a previously-crawled-Web graph using this new method. Using these seeds, a new crawl can be very effective.

Restricting followed links

[edit]A crawler may only want to seek out HTML pages and avoid all other MIME types. In order to request only HTML resources, a crawler may make an HTTP HEAD request to determine a Web resource's MIME type before requesting the entire resource with a GET request. To avoid making numerous HEAD requests, a crawler may examine the URL and only request a resource if the URL ends with certain characters such as .html, .htm, .asp, .aspx, .php, .jsp, .jspx or a slash. This strategy may cause numerous HTML Web resources to be unintentionally skipped.

Some crawlers may also avoid requesting any resources that have a "?" in them (are dynamically produced) in order to avoid spider traps that may cause the crawler to download an infinite number of URLs from a Web site. This strategy is unreliable if the site uses URL rewriting to simplify its URLs.

URL normalization

[edit]Crawlers usually perform some type of URL normalization in order to avoid crawling the same resource more than once. The term URL normalization, also called URL canonicalization, refers to the process of modifying and standardizing a URL in a consistent manner. There are several types of normalization that may be performed including conversion of URLs to lowercase, removal of "." and ".." segments, and adding trailing slashes to the non-empty path component.[20]

Path-ascending crawling

[edit]Some crawlers intend to download/upload as many resources as possible from a particular web site. So path-ascending crawler was introduced that would ascend to every path in each URL that it intends to crawl.[21] For example, when given a seed URL of http://llama.org/hamster/monkey/page.html, it will attempt to crawl /hamster/monkey/, /hamster/, and /. Cothey found that a path-ascending crawler was very effective in finding isolated resources, or resources for which no inbound link would have been found in regular crawling.

Focused crawling

[edit]The importance of a page for a crawler can also be expressed as a function of the similarity of a page to a given query. Web crawlers that attempt to download pages that are similar to each other are called focused crawler or topical crawlers. The concepts of topical and focused crawling were first introduced by Filippo Menczer[22][23] and by Soumen Chakrabarti et al.[24]

The main problem in focused crawling is that in the context of a Web crawler, we would like to be able to predict the similarity of the text of a given page to the query before actually downloading the page. A possible predictor is the anchor text of links; this was the approach taken by Pinkerton[25] in the first web crawler of the early days of the Web. Diligenti et al.[26] propose using the complete content of the pages already visited to infer the similarity between the driving query and the pages that have not been visited yet. The performance of a focused crawling depends mostly on the richness of links in the specific topic being searched, and a focused crawling usually relies on a general Web search engine for providing starting points.

Academic focused crawler

[edit]An example of the focused crawlers are academic crawlers, which crawls free-access academic related documents, such as the citeseerxbot, which is the crawler of CiteSeerX search engine. Other academic search engines are Google Scholar and Microsoft Academic Search etc. Because most academic papers are published in PDF formats, such kind of crawler is particularly interested in crawling PDF, PostScript files, Microsoft Word including their zipped formats. Because of this, general open-source crawlers, such as Heritrix, must be customized to filter out other MIME types, or a middleware is used to extract these documents out and import them to the focused crawl database and repository.[27] Identifying whether these documents are academic or not is challenging and can add a significant overhead to the crawling process, so this is performed as a post crawling process using machine learning or regular expression algorithms. These academic documents are usually obtained from home pages of faculties and students or from publication page of research institutes. Because academic documents make up only a small fraction of all web pages, a good seed selection is important in boosting the efficiencies of these web crawlers.[28] Other academic crawlers may download plain text and HTML files, that contains metadata of academic papers, such as titles, papers, and abstracts. This increases the overall number of papers, but a significant fraction may not provide free PDF downloads.

Semantic focused crawler

[edit]Another type of focused crawlers is semantic focused crawler, which makes use of domain ontologies to represent topical maps and link Web pages with relevant ontological concepts for the selection and categorization purposes.[29] In addition, ontologies can be automatically updated in the crawling process. Dong et al.[30] introduced such an ontology-learning-based crawler using a support-vector machine to update the content of ontological concepts when crawling Web pages.

Re-visit policy

[edit]The Web has a very dynamic nature, and crawling a fraction of the Web can take weeks or months. By the time a Web crawler has finished its crawl, many events could have happened, including creations, updates, and deletions.

From the search engine's point of view, there is a cost associated with not detecting an event, and thus having an outdated copy of a resource. The most-used cost functions are freshness and age.[31]

Freshness: This is a binary measure that indicates whether the local copy is accurate or not. The freshness of a page p in the repository at time t is defined as:

Age: This is a measure that indicates how outdated the local copy is. The age of a page p in the repository, at time t is defined as:

Coffman et al. worked with a definition of the objective of a Web crawler that is equivalent to freshness, but use a different wording: they propose that a crawler must minimize the fraction of time pages remain outdated. They also noted that the problem of Web crawling can be modeled as a multiple-queue, single-server polling system, on which the Web crawler is the server and the Web sites are the queues. Page modifications are the arrival of the customers, and switch-over times are the interval between page accesses to a single Web site. Under this model, mean waiting time for a customer in the polling system is equivalent to the average age for the Web crawler.[32]

The objective of the crawler is to keep the average freshness of pages in its collection as high as possible, or to keep the average age of pages as low as possible. These objectives are not equivalent: in the first case, the crawler is just concerned with how many pages are outdated, while in the second case, the crawler is concerned with how old the local copies of pages are.

Two simple re-visiting policies were studied by Cho and Garcia-Molina:[33]

- Uniform policy: This involves re-visiting all pages in the collection with the same frequency, regardless of their rates of change.

- Proportional policy: This involves re-visiting more often the pages that change more frequently. The visiting frequency is directly proportional to the (estimated) change frequency.

In both cases, the repeated crawling order of pages can be done either in a random or a fixed order.

Cho and Garcia-Molina proved the surprising result that, in terms of average freshness, the uniform policy outperforms the proportional policy in both a simulated Web and a real Web crawl. Intuitively, the reasoning is that, as web crawlers have a limit to how many pages they can crawl in a given time frame, (1) they will allocate too many new crawls to rapidly changing pages at the expense of less frequently updating pages, and (2) the freshness of rapidly changing pages lasts for shorter period than that of less frequently changing pages. In other words, a proportional policy allocates more resources to crawling frequently updating pages, but experiences less overall freshness time from them.

To improve freshness, the crawler should penalize the elements that change too often.[34] The optimal re-visiting policy is neither the uniform policy nor the proportional policy. The optimal method for keeping average freshness high includes ignoring the pages that change too often, and the optimal for keeping average age low is to use access frequencies that monotonically (and sub-linearly) increase with the rate of change of each page. In both cases, the optimal is closer to the uniform policy than to the proportional policy: as Coffman et al. note, "in order to minimize the expected obsolescence time, the accesses to any particular page should be kept as evenly spaced as possible".[32] Explicit formulas for the re-visit policy are not attainable in general, but they are obtained numerically, as they depend on the distribution of page changes. Cho and Garcia-Molina show that the exponential distribution is a good fit for describing page changes,[34] while Ipeirotis et al. show how to use statistical tools to discover parameters that affect this distribution.[35] The re-visiting policies considered here regard all pages as homogeneous in terms of quality ("all pages on the Web are worth the same"), something that is not a realistic scenario, so further information about the Web page quality should be included to achieve a better crawling policy.

Politeness policy

[edit]Crawlers can retrieve data much quicker and in greater depth than human searchers, so they can have a crippling impact on the performance of a site. If a single crawler is performing multiple requests per second and/or downloading large files, a server can have a hard time keeping up with requests from multiple crawlers.

As noted by Koster, the use of Web crawlers is useful for a number of tasks, but comes with a price for the general community.[36] The costs of using Web crawlers include:

- network resources, as crawlers require considerable bandwidth and operate with a high degree of parallelism during a long period of time;

- server overload, especially if the frequency of accesses to a given server is too high;

- poorly written crawlers, which can crash servers or routers, or which download pages they cannot handle; and

- personal crawlers that, if deployed by too many users, can disrupt networks and Web servers.

A partial solution to these problems is the robots exclusion protocol, also known as the robots.txt protocol that is a standard for administrators to indicate which parts of their Web servers should not be accessed by crawlers.[37] This standard does not include a suggestion for the interval of visits to the same server, even though this interval is the most effective way of avoiding server overload. Recently commercial search engines like Google, Ask Jeeves, MSN and Yahoo! Search are able to use an extra "Crawl-delay:" parameter in the robots.txt file to indicate the number of seconds to delay between requests.

The first proposed interval between successive pageloads was 60 seconds.[38] However, if pages were downloaded at this rate from a website with more than 100,000 pages over a perfect connection with zero latency and infinite bandwidth, it would take more than 2 months to download only that entire Web site; also, only a fraction of the resources from that Web server would be used.

Cho uses 10 seconds as an interval for accesses,[33] and the WIRE crawler uses 15 seconds as the default.[39] The MercatorWeb crawler follows an adaptive politeness policy: if it took t seconds to download a document from a given server, the crawler waits for 10t seconds before downloading the next page.[40] Dill et al. use 1 second.[41]

For those using Web crawlers for research purposes, a more detailed cost-benefit analysis is needed and ethical considerations should be taken into account when deciding where to crawl and how fast to crawl.[42]

Anecdotal evidence from access logs shows that access intervals from known crawlers vary between 20 seconds and 3–4 minutes. It is worth noticing that even when being very polite, and taking all the safeguards to avoid overloading Web servers, some complaints from Web server administrators are received. Sergey Brin and Larry Page noted in 1998, "... running a crawler which connects to more than half a million servers ... generates a fair amount of e-mail and phone calls. Because of the vast number of people coming on line, there are always those who do not know what a crawler is, because this is the first one they have seen."[43]

Parallelization policy

[edit]A parallel crawler is a crawler that runs multiple processes in parallel. The goal is to maximize the download rate while minimizing the overhead from parallelization and to avoid repeated downloads of the same page. To avoid downloading the same page more than once, the crawling system requires a policy for assigning the new URLs discovered during the crawling process, as the same URL can be found by two different crawling processes.

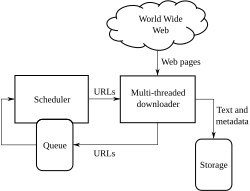

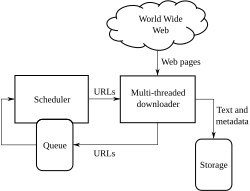

Architectures

[edit]

A crawler must not only have a good crawling strategy, as noted in the previous sections, but it should also have a highly optimized architecture.

Shkapenyuk and Suel noted that:[44]

While it is fairly easy to build a slow crawler that downloads a few pages per second for a short period of time, building a high-performance system that can download hundreds of millions of pages over several weeks presents a number of challenges in system design, I/O and network efficiency, and robustness and manageability.

Web crawlers are a central part of search engines, and details on their algorithms and architecture are kept as business secrets. When crawler designs are published, there is often an important lack of detail that prevents others from reproducing the work. There are also emerging concerns about "search engine spamming", which prevent major search engines from publishing their ranking algorithms.

Security

[edit]While most of the website owners are keen to have their pages indexed as broadly as possible to have strong presence in search engines, web crawling can also have unintended consequences and lead to a compromise or data breach if a search engine indexes resources that should not be publicly available, or pages revealing potentially vulnerable versions of software.

Apart from standard web application security recommendations website owners can reduce their exposure to opportunistic hacking by only allowing search engines to index the public parts of their websites (with robots.txt) and explicitly blocking them from indexing transactional parts (login pages, private pages, etc.).

Crawler identification

[edit]Web crawlers typically identify themselves to a Web server by using the User-agent field of an HTTP request. Web site administrators typically examine their Web servers' log and use the user agent field to determine which crawlers have visited the web server and how often. The user agent field may include a URL where the Web site administrator may find out more information about the crawler. Examining Web server log is tedious task, and therefore some administrators use tools to identify, track and verify Web crawlers. Spambots and other malicious Web crawlers are unlikely to place identifying information in the user agent field, or they may mask their identity as a browser or other well-known crawler.

Web site administrators prefer Web crawlers to identify themselves so that they can contact the owner if needed. In some cases, crawlers may be accidentally trapped in a crawler trap or they may be overloading a Web server with requests, and the owner needs to stop the crawler. Identification is also useful for administrators that are interested in knowing when they may expect their Web pages to be indexed by a particular search engine.

Crawling the deep web

[edit]A vast amount of web pages lie in the deep or invisible web.[45] These pages are typically only accessible by submitting queries to a database, and regular crawlers are unable to find these pages if there are no links that point to them. Google's Sitemaps protocol and mod oai[46] are intended to allow discovery of these deep-Web resources.

Deep web crawling also multiplies the number of web links to be crawled. Some crawlers only take some of the URLs in <a href="URL"> form. In some cases, such as the Googlebot, Web crawling is done on all text contained inside the hypertext content, tags, or text.

Strategic approaches may be taken to target deep Web content. With a technique called screen scraping, specialized software may be customized to automatically and repeatedly query a given Web form with the intention of aggregating the resulting data. Such software can be used to span multiple Web forms across multiple Websites. Data extracted from the results of one Web form submission can be taken and applied as input to another Web form thus establishing continuity across the Deep Web in a way not possible with traditional web crawlers.[47]

Pages built on AJAX are among those causing problems to web crawlers. Google has proposed a format of AJAX calls that their bot can recognize and index.[48]

Visual vs programmatic crawlers

[edit]There are a number of "visual web scraper/crawler" products available on the web which will crawl pages and structure data into columns and rows based on the users requirements. One of the main difference between a classic and a visual crawler is the level of programming ability required to set up a crawler. The latest generation of "visual scrapers" remove the majority of the programming skill needed to be able to program and start a crawl to scrape web data.

The visual scraping/crawling method relies on the user "teaching" a piece of crawler technology, which then follows patterns in semi-structured data sources. The dominant method for teaching a visual crawler is by highlighting data in a browser and training columns and rows. While the technology is not new, for example it was the basis of Needlebase which has been bought by Google (as part of a larger acquisition of ITA Labs[49]), there is continued growth and investment in this area by investors and end-users.[citation needed]

List of web crawlers

[edit]The following is a list of published crawler architectures for general-purpose crawlers (excluding focused web crawlers), with a brief description that includes the names given to the different components and outstanding features:

Historical web crawlers

[edit]- WolfBot was a massively multi threaded crawler built in 2001 by Mani Singh a Civil Engineering graduate from the University of California at Davis.

- World Wide Web Worm was a crawler used to build a simple index of document titles and URLs. The index could be searched by using the grep Unix command.

- Yahoo! Slurp was the name of the Yahoo! Search crawler until Yahoo! contracted with Microsoft to use Bingbot instead.

In-house web crawlers

[edit]- Applebot is Apple's web crawler. It supports Siri and other products.[50]

- Bingbot is the name of Microsoft's Bing webcrawler. It replaced Msnbot.

- Baiduspider is Baidu's web crawler.

- DuckDuckBot is DuckDuckGo's web crawler.

- Googlebot is described in some detail, but the reference is only about an early version of its architecture, which was written in C++ and Python. The crawler was integrated with the indexing process, because text parsing was done for full-text indexing and also for URL extraction. There is a URL server that sends lists of URLs to be fetched by several crawling processes. During parsing, the URLs found were passed to a URL server that checked if the URL have been previously seen. If not, the URL was added to the queue of the URL server.

- WebCrawler was used to build the first publicly available full-text index of a subset of the Web. It was based on lib-WWW to download pages, and another program to parse and order URLs for breadth-first exploration of the Web graph. It also included a real-time crawler that followed links based on the similarity of the anchor text with the provided query.

- WebFountain is a distributed, modular crawler similar to Mercator but written in C++.

- Xenon is a web crawler used by government tax authorities to detect fraud.[51][52]

Commercial web crawlers

[edit]The following web crawlers are available, for a price::

- Diffbot - programmatic general web crawler, available as an API

- SortSite - crawler for analyzing websites, available for Windows and Mac OS

- Swiftbot - Swiftype's web crawler, available as software as a service

- Aleph Search - web crawler allowing massive collection with high scalability

Open-source crawlers

[edit]- Apache Nutch is a highly extensible and scalable web crawler written in Java and released under an Apache License. It is based on Apache Hadoop and can be used with Apache Solr or Elasticsearch.

- Grub was an open source distributed search crawler that Wikia Search used to crawl the web.

- Heritrix is the Internet Archive's archival-quality crawler, designed for archiving periodic snapshots of a large portion of the Web. It was written in Java.

- ht://Dig includes a Web crawler in its indexing engine.

- HTTrack uses a Web crawler to create a mirror of a web site for off-line viewing. It is written in C and released under the GPL.

- Norconex Web Crawler is a highly extensible Web Crawler written in Java and released under an Apache License. It can be used with many repositories such as Apache Solr, Elasticsearch, Microsoft Azure Cognitive Search, Amazon CloudSearch and more.

- mnoGoSearch is a crawler, indexer and a search engine written in C and licensed under the GPL (*NIX machines only)

- Open Search Server is a search engine and web crawler software release under the GPL.

- Scrapy, an open source webcrawler framework, written in python (licensed under BSD).

- Seeks, a free distributed search engine (licensed under AGPL).

- StormCrawler, a collection of resources for building low-latency, scalable web crawlers on Apache Storm (Apache License).

- tkWWW Robot, a crawler based on the tkWWW web browser (licensed under GPL).

- GNU Wget is a command-line-operated crawler written in C and released under the GPL. It is typically used to mirror Web and FTP sites.

- YaCy, a free distributed search engine, built on principles of peer-to-peer networks (licensed under GPL).

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Web Crawlers: Browsing the Web". Archived from the original on 6 December 2021.

- ^ Spetka, Scott. "The TkWWW Robot: Beyond Browsing". NCSA. Archived from the original on 3 September 2004. Retrieved 21 November 2010.

- ^ Kobayashi, M. & Takeda, K. (2000). "Information retrieval on the web". ACM Computing Surveys. 32 (2): 144–173. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.126.6094. doi:10.1145/358923.358934. S2CID 3710903.

- ^ See definition of scutter on FOAF Project's wiki Archived 13 December 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Masanès, Julien (15 February 2007). Web Archiving. Springer. p. 1. ISBN 978-3-54046332-0. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ Edwards, J.; McCurley, K. S.; and Tomlin, J. A. (2001). "An adaptive model for optimizing performance of an incremental web crawler". Proceedings of the 10th international conference on World Wide Web. pp. 106–113. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1018.1506. doi:10.1145/371920.371960. ISBN 978-1581133486. S2CID 10316730. Archived from the original on 25 June 2014. Retrieved 25 January 2007.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Castillo, Carlos (2004). Effective Web Crawling (PhD thesis). University of Chile. Retrieved 3 August 2010.

- ^ Gulls, A.; A. Signori (2005). "The indexable web is more than 11.5 billion pages". Special interest tracks and posters of the 14th international conference on World Wide Web. ACM Press. pp. 902–903. doi:10.1145/1062745.1062789.

- ^ Lawrence, Steve; C. Lee Giles (8 July 1999). "Accessibility of information on the web". Nature. 400 (6740): 107–9. Bibcode:1999Natur.400..107L. doi:10.1038/21987. PMID 10428673. S2CID 4347646.

- ^ "Using the robots meta tag". Google Developers Blog. Google. Retrieved 1 November 2025.

- ^ "Are Your Login Pages Hurting SEO? – blog". Primotech. Primotech. Retrieved 1 November 2025.

- ^ Cho, J.; Garcia-Molina, H.; Page, L. (April 1998). "Efficient Crawling Through URL Ordering". Seventh International World-Wide Web Conference. Brisbane, Australia. doi:10.1142/3725. ISBN 978-981-02-3400-3. Retrieved 23 March 2009.

- ^ Cho, Junghoo, "Crawling the Web: Discovery and Maintenance of a Large-Scale Web Data", PhD dissertation, Department of Computer Science, Stanford University, November 2001.

- ^ Najork, Marc and Janet L. Wiener. "Breadth-first crawling yields high-quality pages". Archived 24 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine In: Proceedings of the Tenth Conference on World Wide Web, pages 114–118, Hong Kong, May 2001. Elsevier Science.

- ^ Abiteboul, Serge; Mihai Preda; Gregory Cobena (2003). "Adaptive on-line page importance computation". Proceedings of the 12th international conference on World Wide Web. Budapest, Hungary: ACM. pp. 280–290. doi:10.1145/775152.775192. ISBN 1-58113-680-3. Retrieved 22 March 2009.

- ^ Boldi, Paolo; Bruno Codenotti; Massimo Santini; Sebastiano Vigna (2004). "UbiCrawler: a scalable fully distributed Web crawler" (PDF). Software: Practice and Experience. 34 (8): 711–726. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.2.5538. doi:10.1002/spe.587. S2CID 325714. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 March 2009. Retrieved 23 March 2009.

- ^ Boldi, Paolo; Massimo Santini; Sebastiano Vigna (2004). "Do Your Worst to Make the Best: Paradoxical Effects in PageRank Incremental Computations" (PDF). Algorithms and Models for the Web-Graph. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 3243. pp. 168–180. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-30216-2_14. ISBN 978-3-540-23427-2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 October 2005. Retrieved 23 March 2009.

- ^ Baeza-Yates, R.; Castillo, C.; Marin, M. and Rodriguez, A. (2005). "Crawling a Country: Better Strategies than Breadth-First for Web Page Ordering." In: Proceedings of the Industrial and Practical Experience track of the 14th conference on World Wide Web, pages 864–872, Chiba, Japan. ACM Press.

- ^ Shervin Daneshpajouh, Mojtaba Mohammadi Nasiri, Mohammad Ghodsi, A Fast Community Based Algorithm for Generating Crawler Seeds Set. In: Proceedings of 4th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies (Webist-2008), Funchal, Portugal, May 2008.

- ^ Pant, Gautam; Srinivasan, Padmini; Menczer, Filippo (2004). "Crawling the Web" (PDF). In Levene, Mark; Poulovassilis, Alexandra (eds.). Web Dynamics: Adapting to Change in Content, Size, Topology and Use. Springer. pp. 153–178. ISBN 978-3-540-40676-1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 March 2009. Retrieved 9 May 2006.

- ^ Cothey, Viv (2004). "Web-crawling reliability" (PDF). Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology. 55 (14): 1228–1238. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.117.185. doi:10.1002/asi.20078. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 September 2017. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ^ Menczer, F. (1997). ARACHNID: Adaptive Retrieval Agents Choosing Heuristic Neighborhoods for Information Discovery Archived 21 December 2012 at the Wayback Machine. In D. Fisher, ed., Machine Learning: Proceedings of the 14th International Conference (ICML97). Morgan Kaufmann

- ^ Menczer, F. and Belew, R.K. (1998). Adaptive Information Agents in Distributed Textual Environments Archived 21 December 2012 at the Wayback Machine. In K. Sycara and M. Wooldridge (eds.) Proc. 2nd Intl. Conf. on Autonomous Agents (Agents '98). ACM Press

- ^ Chakrabarti, Soumen; Van Den Berg, Martin; Dom, Byron (1999). "Focused crawling: A new approach to topic-specific Web resource discovery" (PDF). Computer Networks. 31 (11–16): 1623–1640. doi:10.1016/s1389-1286(99)00052-3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 March 2004.

- ^ Pinkerton, B. (1994). Finding what people want: Experiences with the WebCrawler. In Proceedings of the First World Wide Web Conference, Geneva, Switzerland.

- ^ Diligenti, M., Coetzee, F., Lawrence, S., Giles, C. L., and Gori, M. (2000). Focused crawling using context graphs. In Proceedings of 26th International Conference on Very Large Databases (VLDB), pages 527-534, Cairo, Egypt.

- ^ Wu, Jian; Teregowda, Pradeep; Khabsa, Madian; Carman, Stephen; Jordan, Douglas; San Pedro Wandelmer, Jose; Lu, Xin; Mitra, Prasenjit; Giles, C. Lee (2012). "Web crawler middleware for search engine digital libraries". Proceedings of the twelfth international workshop on Web information and data management - WIDM '12. p. 57. doi:10.1145/2389936.2389949. ISBN 9781450317207. S2CID 18513666.

- ^ Wu, Jian; Teregowda, Pradeep; Ramírez, Juan Pablo Fernández; Mitra, Prasenjit; Zheng, Shuyi; Giles, C. Lee (2012). "The evolution of a crawling strategy for an academic document search engine". Proceedings of the 3rd Annual ACM Web Science Conference on - Web Sci '12. pp. 340–343. doi:10.1145/2380718.2380762. ISBN 9781450312288. S2CID 16718130.

- ^ Dong, Hai; Hussain, Farookh Khadeer; Chang, Elizabeth (2009). "State of the Art in Semantic Focused Crawlers". Computational Science and Its Applications – ICCSA 2009. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 5593. pp. 910–924. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-02457-3_74. hdl:20.500.11937/48288. ISBN 978-3-642-02456-6.

- ^ Dong, Hai; Hussain, Farookh Khadeer (2013). "SOF: A semi-supervised ontology-learning-based focused crawler". Concurrency and Computation: Practice and Experience. 25 (12): 1755–1770. doi:10.1002/cpe.2980. S2CID 205690364.

- ^ Junghoo Cho; Hector Garcia-Molina (2000). "Synchronizing a database to improve freshness" (PDF). Proceedings of the 2000 ACM SIGMOD international conference on Management of data. Dallas, Texas, United States: ACM. pp. 117–128. doi:10.1145/342009.335391. ISBN 1-58113-217-4. Retrieved 23 March 2009.

- ^ a b E. G. Coffman Jr; Zhen Liu; Richard R. Weber (1998). "Optimal robot scheduling for Web search engines". Journal of Scheduling. 1 (1): 15–29. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.36.6087. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1425(199806)1:1<15::AID-JOS3>3.0.CO;2-K.

- ^ a b Cho, Junghoo; Garcia-Molina, Hector (2003). "Effective page refresh policies for Web crawlers". ACM Transactions on Database Systems. 28 (4): 390–426. doi:10.1145/958942.958945. S2CID 147958.

- ^ a b Junghoo Cho; Hector Garcia-Molina (2003). "Estimating frequency of change". ACM Transactions on Internet Technology. 3 (3): 256–290. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.59.5877. doi:10.1145/857166.857170. S2CID 9362566.

- ^ Ipeirotis, P., Ntoulas, A., Cho, J., Gravano, L. (2005) Modeling and managing content changes in text databases Archived 5 September 2005 at the Wayback Machine. In Proceedings of the 21st IEEE International Conference on Data Engineering, pages 606-617, April 2005, Tokyo.

- ^ Koster, M. (1995). Robots in the web: threat or treat? ConneXions, 9(4).

- ^ Koster, M. (1996). A standard for robot exclusion Archived 7 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Koster, M. (1993). Guidelines for robots writers Archived 22 April 2005 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Baeza-Yates, R. and Castillo, C. (2002). Balancing volume, quality and freshness in Web crawling. In Soft Computing Systems – Design, Management and Applications, pages 565–572, Santiago, Chile. IOS Press Amsterdam.

- ^ Heydon, Allan; Najork, Marc (26 June 1999). "Mercator: A Scalable, Extensible Web Crawler" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 February 2006. Retrieved 22 March 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Dill, S.; Kumar, R.; Mccurley, K. S.; Rajagopalan, S.; Sivakumar, D.; Tomkins, A. (2002). "Self-similarity in the web" (PDF). ACM Transactions on Internet Technology. 2 (3): 205–223. doi:10.1145/572326.572328. S2CID 6416041.

- ^ M. Thelwall; D. Stuart (2006). "Web crawling ethics revisited: Cost, privacy and denial of service". Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology. 57 (13): 1771–1779. doi:10.1002/asi.20388.

- ^ Brin, Sergey; Page, Lawrence (1998). "The anatomy of a large-scale hypertextual Web search engine". Computer Networks and ISDN Systems. 30 (1–7): 107–117. doi:10.1016/s0169-7552(98)00110-x. S2CID 7587743.

- ^ Shkapenyuk, V. and Suel, T. (2002). Design and implementation of a high performance distributed web crawler Archived 1 October 2005 at the Wayback Machine. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Data Engineering (ICDE), pages 357-368, San Jose, California. IEEE CS Press.

- ^ Shestakov, Denis (2008). Search Interfaces on the Web: Querying and Characterizing Archived 6 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine. TUCS Doctoral Dissertations 104, University of Turku

- ^ Michael L Nelson; Herbert Van de Sompel; Xiaoming Liu; Terry L Harrison; Nathan McFarland (24 March 2005). "mod_oai: An Apache Module for Metadata Harvesting": cs/0503069. arXiv:cs/0503069. Bibcode:2005cs........3069N.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Shestakov, Denis; Bhowmick, Sourav S.; Lim, Ee-Peng (2005). "DEQUE: Querying the Deep Web" (PDF). Data & Knowledge Engineering. 52 (3): 273–311. doi:10.1016/s0169-023x(04)00107-7.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "AJAX crawling: Guide for webmasters and developers". Archived from the original on 6 March 2013. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ^ ITA Labs "ITA Labs Acquisition" Archived 18 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine 20 April 2011 1:28 AM

- ^ "About Applebot". Apple Inc. Retrieved 18 October 2021.

- ^ Norton, Quinn (25 January 2007). "Tax takers send in the spiders". Business. Wired. Archived from the original on 22 December 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ^ "Xenon web crawling initiative: privacy impact assessment (PIA) summary". Ottawa: Government of Canada. 11 April 2017. Archived from the original on 25 September 2017. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

Further reading

[edit]- Cho, Junghoo, "Web Crawling Project", UCLA Computer Science Department.

- A History of Search Engines, from Wiley

- WIVET is a benchmarking project by OWASP, which aims to measure if a web crawler can identify all the hyperlinks in a target website.

- Shestakov, Denis, "Current Challenges in Web Crawling" and "Intelligent Web Crawling", slides for tutorials given at ICWE'13 and WI-IAT'13.