Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cortical reaction

View on Wikipedia| Cortical reaction | |

|---|---|

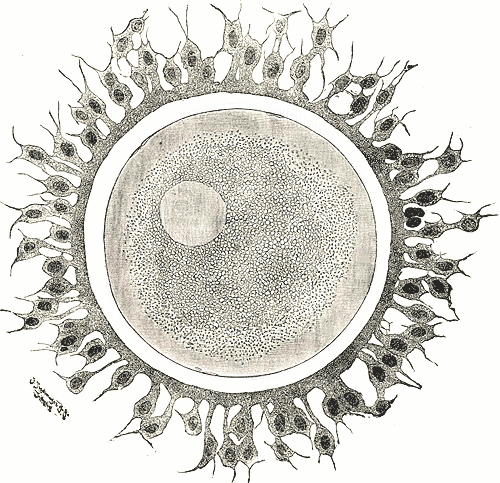

Human ovum. The zona pellucida is seen as a thick clear girdle surrounded by the cells of the corona radiata. | |

| Anatomical terminology |

The cortical reaction is a process initiated during fertilization that prevents polyspermy, the fusion of multiple sperm with one egg. In contrast to the fast block of polyspermy which immediately but temporarily blocks additional sperm from fertilizing the egg, the cortical reaction gradually establishes a permanent barrier to sperm entry and functions as the main part of the slow block of polyspermy in many animals.

To create this barrier, cortical granules, specialized secretory vesicles located within the egg's cortex (the region directly below the plasma membrane), are fused with the egg's plasma membrane. This releases the contents of the cortical granules outside the cell, where they modify an existing extracellular matrix to make it impenetrable to sperm entry. The cortical granules contain proteases that clip perivitelline tether proteins, peroxidases that harden the vitelline envelope, and glycosaminoglycans that attract water into the perivitelline space, causing it to expand and form the hyaline layer. The trigger for the cortical granules to exocytose is the release of calcium ions from cortical smooth endoplasmic reticulum in response to sperm binding to the egg.

The migration of cortical granules from their synthesis in the Golgi apparatus to the cortex region has been shown to be mediated by actin filaments in frogs and mice, and by microtubules in other mammals.[1] This migration is commonly used to assess and classify the maturity of developing oocytes.[2]

In most animals, the extracellular matrix present around the egg is the vitelline envelope which becomes the fertilization membrane following the cortical reaction. In mammals, however, the extracellular matrix modified by the cortical reaction is the zona pellucida. This modification of the zona pellucida is known as the zona reaction or zona hardening. Although highly conserved across the animal kingdom, the cortical reaction shows great diversity between species. While much has been learned about the identity and function of the contents of the cortical granules in the highly accessible sea urchin, little is known about the contents of cortical granules in mammals.

The cortical reaction within the egg is analogous to the acrosomal reaction within the sperm, where the acrosome, a specialized secretory vesicle that is homologous to cortical granules, is fused with the plasma membrane of the sperm cell to release its contents which degrade the egg's tough coating and allow the sperm to bind to and fuse with the egg.

Discovery

[edit]The cortical reaction and cortical granules were first observed by Ethel Brown Harvey in 1910 in sea urchins. The fertilization membrane had been previously defined by Derbès when he observed the fusion of sperm and eggs of sea urchins; however, scientists believed that seminal fluid or other chemicals that the sperm brought into the egg caused the hardening of the fertilization membrane.[3] E. B. Harvey studied the mechanisms after sperm contact that lead to calcium release and formation of the fertilization membrane.[4] Cortical granules were discovered in vertebrates first in hamster oocytes in 1956 by C. R. Austin using a phase contrast microscope.[1]

Echinoderms

[edit]

In the well-studied sea urchin model system, the granule contents modify a protein coat on the outside of the plasma membrane (the vitelline layer) so that it is released from the membrane. The released cortical granule proteins exert a colloid osmotic pressure causing water to enter the space between the plasma membrane and the vitelline layer, and the vitelline layer expands away from the egg surface. This is easily visible through a microscope and is known as "elevation of the fertilization envelope". Some of the former granule contents adhere to the fertilization envelope, and it is extensively modified and cross-linked. As the fertilization envelope elevates, non-fertilizing sperm are lifted away from the egg plasma membrane, and as they are not able to pass through the fertilization envelope, they are prevented from entering the egg. Therefore, the cortical reaction prevents polyspermic fertilization, a lethal event. Another cortical granule component, polysaccharide-rich hyalin, remains adherent to the outer surface of the plasma membrane, and becomes part of the hyaline layer.

Mammals

[edit]Although various mammals have been studied, mice represent the best studied animal models for understanding the cortical reaction in mammals. Most mammalian cortical granules are 0.2 - 0.6 um in diameter.[2] The cortical granules associate with the oocyte membrane due to SNARE proteins, which form a stabilizing complex with other proteins.[2][5] Upon contact of the sperm with the oocyte membrane, a calcium wave is induced through the PIP2 pathway involving IP3 production. IP3 then binds to its receptor on the endoplasmic reticulum which triggers a release of calcium into the cytoplasm.[2] The release of calcium triggers a change in the SNARE protein complex, and the conformation facilitates the fusion of the cortical granule with the oocyte membrane, releasing granules into the perivitelline space. The cortical reaction leads to a modification of the zona pellucida that blocks polyspermy; enzymes released by cortical granules digest sperm receptor glycoproteins ZP2 and ZP3 so that they can no longer bind spermatozoon. This is often referred to as zona hardening.

See also

[edit]- Acrosome reaction - The analogous reaction in the acrosome of the sperm

References

[edit]- ^ a b Rojas, Japhet; Hinostroza, Fernando; Vergara, Sebastián; Pinto-Borguero, Ingrid; Aguilera, Felipe; Fuentes, Ricardo; Carvacho, Ingrid (2021-09-03). "Knockin' on Egg's Door: Maternal Control of Egg Activation That Influences Cortical Granule Exocytosis in Animal Species". Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology. 9. doi:10.3389/fcell.2021.704867. ISSN 2296-634X. PMC 8446563. PMID 34540828.

- ^ a b c d Liu, Min (2011). "The biology and dynamics of mammalian cortical granules". Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology. 9 (1): 149. doi:10.1186/1477-7827-9-149. ISSN 1477-7827. PMC 3228701. PMID 22088197.

- ^ Briggs, Elissa; Wessel, Gary M. (2006-12-01). "In the beginning… Animal fertilization and sea urchin development". Developmental Biology. Sea Urchin Genome: Implications and Insights. 300 (1): 15–26. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.07.014. ISSN 0012-1606. PMID 17070796.

- ^ Harvey, E. Newton (1910). "The mechanism of membrane formation and other early changes in developing seaurchins' eggs as bearing on the problem of artificial parthenogenesis". Journal of Experimental Zoology. 8 (4): 355–376. Bibcode:1910JEZ.....8..355H. doi:10.1002/jez.1400080402. ISSN 1097-010X.

- ^ Tsai, P.-S.; van Haeften, T.; Gadella, B. M. (2011-02-01). "Preparation of the Cortical Reaction: Maturation-Dependent Migration of SNARE Proteins, Clathrin, and Complexin to the Porcine Oocyte's Surface Blocks Membrane Traffic until Fertilization". Biology of Reproduction. 84 (2): 327–335. doi:10.1095/biolreprod.110.085647. ISSN 0006-3363. PMID 20944080.

- Haley SA, Wessel GM. Sea urchin cortical granules regulated proteolysis by cortical granule serine protease 1 at fertilisation. Mol Biol Cell. 2004 May;15(5):2084-92.

- Sadler TW. Langman's Medical Embryology. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2006.