Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

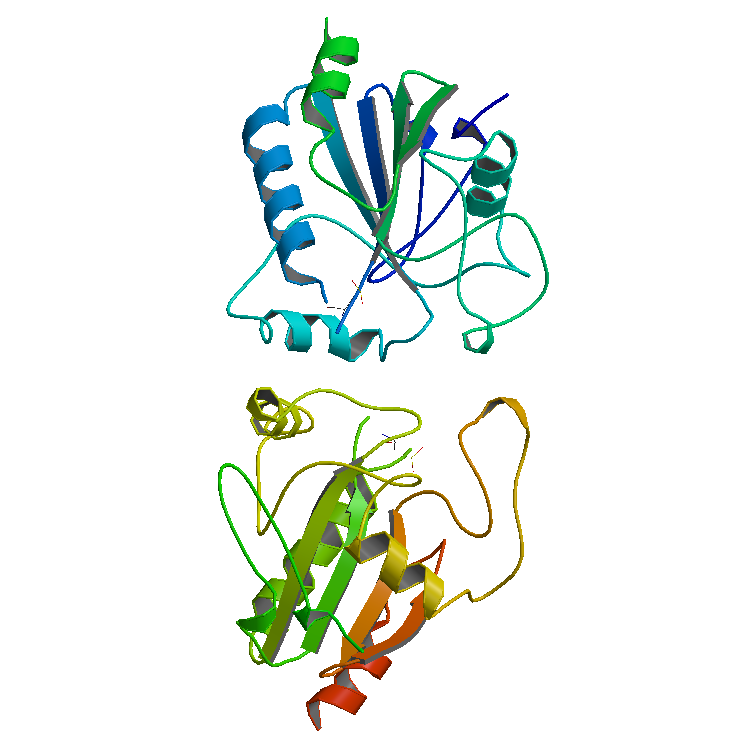

Peroxidase

View on Wikipedia

Peroxidases or peroxide reductases (EC number 1.11.1.x) are a large group of enzymes which play a role in various biological processes. They are named after the fact that they commonly break up peroxides, and should not be confused with other enzymes that produce peroxide, which are often oxidases.

Functionality

[edit]Peroxidases typically catalyze a reaction of the form:

Optimal substrates

[edit]For many of these enzymes the optimal substrate is hydrogen peroxide, but others are more active with organic hydroperoxides such as lipid peroxides. Peroxidases can contain a heme cofactor in their active sites, or alternately redox-active cysteine or selenocysteine residues.

The nature of the electron donor is very dependent on the structure of the enzyme.

- For example, horseradish peroxidase can use a variety of organic compounds as electron donors and acceptors. Horseradish peroxidase has an accessible active site, and many compounds can reach the site of the reaction.

- On the other hand, for an enzyme such as cytochrome c peroxidase, the compounds that donate electrons are very specific, due to a very narrow active site.

Classification

[edit]Protein families that serve as peroxidases include:[1]

- Haem-using

- Non-heme

- Thiol: glutathione peroxidase, peroxiredoxin

- vanadium bromoperoxidase

- Alkyl hydroperoxide reductase

- Manganese peroxidase

- NADH peroxidase

Characterization

[edit]The glutathione peroxidase family consists of 8 known human isoforms. Glutathione peroxidases use glutathione as an electron donor and are active with both hydrogen peroxide and organic hydroperoxide substrates. Gpx1, Gpx2, Gpx3, and Gpx4 have been shown to be selenium-containing enzymes, whereas Gpx6 is a selenoprotein in humans with cysteine-containing homologues in rodents.

Amyloid beta, when bound to heme, has been shown to have peroxidase activity.[2]

A typical group of peroxidases are the haloperoxidases. This group is able to form reactive halogen species and, as a result, natural organohalogen substances.

A majority of peroxidase protein sequences can be found in the PeroxiBase database.

Pathogenic resistance

[edit]While the exact mechanisms have yet to be determined, peroxidases are known to play a part in increasing a plant's defenses against pathogens.[3] Many members of the Solanaceae, notably Solanum melongena (eggplant/aubergine) and Capsicum chinense (the habanero/Scotch bonnet varieties of chili peppers) use Guaiacol and the enzyme guaiacol peroxidase as a defense against bacterial parasites such as Ralstonia solanacearum: the gene expression for this enzyme commences within minutes of bacterial attack.[4]

Applications

[edit]Peroxidase can be used for treatment of industrial waste waters. For example, phenols, which are important pollutants, can be removed by enzyme-catalyzed polymerization using horseradish peroxidase. Thus phenols are oxidized to phenoxy radicals, which participate in reactions where polymers and oligomers are produced that are less toxic than phenols. It also can be used to convert toxic materials into less harmful substances.

There are many investigations about the use of peroxidase in many manufacturing processes like adhesives, computer chips, car parts, and linings of drums and cans. Other studies have shown that peroxidases may be used successfully to polymerize anilines and phenols in organic solvent matrices.[5]

Peroxidases are sometimes used as histological markers. Cytochrome c peroxidase is used as a soluble, easily purified model for cytochrome c oxidase.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "RedOxiBase: Peroxidase Classes". Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- ^ Atamna H, Boyle K (February 2006). "Amyloid-beta peptide binds with heme to form a peroxidase: relationship to the cytopathologies of Alzheimer's disease". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 103 (9): 3381–6. Bibcode:2006PNAS..103.3381A. doi:10.1073/pnas.0600134103. PMC 1413946. PMID 16492752.

- ^ Karthikeyan M, Jayakumar V, Radhika K, Bhaskaran R, Velazhahan R, Alice D (December 2005). "Induction of resistance in host against the infection of leaf blight pathogen (Alternaria palandui) in onion (Allium cepa var aggregatum)". Indian Journal of Biochemistry & Biophysics. 42 (6): 371–7. PMID 16955738.

- ^ Prakasha, A, Umesha, S. Biochemical and Molecular Variations of Guaiacol Peroxidase and Total Phenols in Bacterial Wilt Pathogenesis of Solanum melongena. Biochemistry & Analytical Biochemistry, 5,292, 2016

- ^ Tuhela, L., G. K. Sims, and O. Tuovinen. 1989. Polymerization of substituted anilines, phenols, and heterocyclic compounds by peroxidase in organic solvents. Columbus, Ohio: The Ohio State University. 58 pages.

External links

[edit]- Peroxibase, a database of peroxidases