Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Starfish

View on Wikipedia

| Starfish Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Clockwise from top left: Linckia laevigata, Echinaster serpentarius, Protoreaster nodosus, and Hymnaster pellucidus. Not to scale. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Echinodermata |

| Subphylum: | Asterozoa |

| Class: | Asteroidea Blainville, 1830 |

| Child taxa and orders | |

| |

| Diversity | |

| 1,900+ species | |

Starfish or sea stars are a class of marine invertebrates generally shaped like a star polygon. (In common usage, these names are also often applied to ophiuroids, which are correctly referred to as brittle stars or basket stars.) Starfish are also known as asteroids because they form the taxonomic class Asteroidea (/ˌæstəˈrɔɪdiə/). About 1,900 species of starfish live on the seabed, and are found in all the world's oceans, from warm, tropical zones to frigid, polar regions. They can occur from the intertidal zone down to abyssal depths, at 6,000 m (20,000 ft) below the surface.

Starfish are echinoderms and typically have a central disc and usually five arms, though some species have a larger number of arms. The aboral or upper surface may be smooth, granular or spiny, and is covered with overlapping plates. Many species are brightly coloured in various shades of red or orange, while others are blue, grey or brown. Starfish have tube feet operated by a hydraulic system and a mouth at the centre of the oral or lower surface. They are opportunistic feeders and are mostly predators on benthic invertebrates. Several species have specialized feeding behaviours including eversion of their stomachs and suspension feeding. They have complex life cycles and can reproduce both sexually and asexually. Most can regenerate damaged parts or lost arms and they can shed arms as a means of defense.

The Asteroidea occupy several significant ecological roles. Some, such as the ochre sea star (Pisaster ochraceus) and the reef sea star (Stichaster australis), serve as keystone species, with an outsize impact on their environment. The tropical crown-of-thorns starfish (Acanthaster planci) is a voracious predator of coral throughout the Indo-Pacific region, and the Northern Pacific seastar is on a list of the Worst Invasive Alien Species.

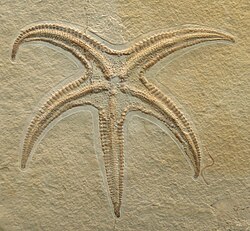

The fossil record for starfish is ancient, dating back to the Ordovician period around 450 million years ago, but it is rather sparse, as starfish tend to disintegrate after death. Only the ossicles and spines of the animal are likely to be preserved, making remains hard to locate. With their appealing symmetrical shape, starfish have played a part in literature and legend. They are sometimes collected as curios, used in design or as logos, and in some cultures they are eaten.

Anatomy

[edit]Most starfish have five arms that radiate from a central disc, but the number varies with the group. Some species have six or seven arms and others have 10–15 arms.[3] In Antarctic Labidiaster annulatus, the number of arms can exceed fifty.[4] Evidence from gene expression finds that the starfish body corresponds to a head externally (with lips attached to the tube feet) and a torso internally.[5] Starfish possess two vascular systems, one for transport of water to support locomotion and other functions, and another for circulation of blood.

Body wall

[edit]The body wall layers include a thin cuticle, an epidermis consisting of a single layer of cells, a thick dermis formed of connective tissue, a thin coelomic myoepithelial layer for the muscles, and a peritoneum. The dermis contains an endoskeleton of calcium carbonate components known as ossicles. These are honeycomb-like structures composed of calcite microcrystals arranged in a lattice.[6] They vary in form, from flat plates to granules to spines, and cover the aboral surface.[7] Some are specialised structures such as the madreporite (the entrance to the water vascular system), pedicellariae, and paxillae. Paxillae are umbrella-like structures found on starfish that live buried in substrate. The edges of adjacent paxillae meet to form a false cuticle with a water cavity beneath in which the madreporite and delicate gill structures are protected. The ossicles are located under the epidermal layer, even those emerging externally.[6]

Several groups of starfish, including Valvatida and Forcipulatida, possess pedicellariae.[8] These are scissor-like ossicles at the tip of the spine which displace organisms from resting on the starfish's surface.[9][10] Some species like Labidiaster annulatus and Novodinia antillensis use their pedicellariae to catch prey.[11] There may also be papulae, thin-walled protrusions of the body cavity that reach through the body wall into the surrounding water. These serve a respiratory function.[12] The structures are supported by collagen fibres set at right angles to each other and arranged in a three-dimensional web with the ossicles and papulae in the interstices. This arrangement enables both easy flexion of the arms and the rapid onset of stiffness and rigidity required for some actions performed under stress.[13]

-

Luidia maculata, a seven armed starfish

-

Pedicellariae and retracted papulae among the spines of Acanthaster planci

-

Pedicellaria and papulae of Asterias forbesi

Water vascular system

[edit]The water vascular system of the starfish is a hydraulic system made up of a network of fluid-filled canals and is concerned with locomotion, adhesion, food manipulation and gas exchange. Water enters the system through the madreporite, a porous, often conspicuous, sieve-like ossicle on the aboral surface. It is linked through a calcareous-lined canal called the stone canal, to a ring canal around the mouth opening. A set of radial canals branch off from the ring canal; one radial canal runs along the ambulacral groove in each arm. There are short lateral canals branching off alternately to either side of the radial canal, each ending in an ampulla. These bulb-shaped organs are joined to tube feet (podia) on the exterior of the animal by short linking canals that pass through ossicles in the ambulacral groove. There are usually two rows of tube feet but in some species, the lateral canals are alternately long and short and there appear to be four rows. The interior of the whole canal system is lined with cilia.[14]

Water is pushed into the tube face when longitudinal muscles in the ampullae contract, and shut the valves in the lateral canals. This causes the tube feet to stretch and touch the substrate.[14] Although the tube feet resemble suction cups in appearance, the gripping action is a function of adhesive chemicals rather than suction.[15] Other chemicals and relaxation of the ampullae allow for release from the substrate. The tube feet latch on to surfaces and move in a wave, with one arm section attaching to the surface as another releases.[16][17] To expose the sensory tube feet and the eyespot to external stimuli, some starfish turn up the tips of their arms while moving.[18]

Having descended from bilateral organisms, starfish may move in a bilateral fashion, particularly when hunting or threatened. When crawling, certain arms act as the leading arms, while others trail behind. When a starfish finds itself upside down, two adjacent arms and an opposite arm press against the ground to lift up the two remaining arms; the opposite arm leaves the ground as the starfish turns over and recovers its normal stance.[19]

Apart from their function in locomotion, the tube feet act as accessory gills. The water vascular system serves to transport oxygen from, and carbon dioxide to, the tube feet and nutrients from the gut to the muscles involved in locomotion. Fluid movement is bidirectional and initiated by cilia.[14]

-

Video showing the tube feet movement of a starfish

-

Arm tip of Leptasterias polaris showing tube feet and eyespot

Digestive system and excretion

[edit]

- Pyloric stomach

- Intestine and anus

- Rectal sac

- Stone canal

- Madreporite

- Pyloric caecum

- Digestive glands

- Cardiac stomach

- Gonad

- Radial canal

- Ambulacral ridge

The gut of a starfish fills most of the central disc and extends into the arms. The mouth occupies the centre of the oral surface, where it is surrounded by a tough peristomial membrane and closed with a sphincter. A short oesophagus connects the mouth to a stomach, which consists of an eversible cardial portion and a smaller pyloric portion. The cardial stomach is glandular and pouched, and is supported by ligaments attached to ossicles in the arms so it can be pulled back into position after it has been everted. The pyloric stomach has two extensions into each arm: the pyloric caeca. These are long, hollow tubes lined by a series of glands which secrete digestive enzymes and absorb nutrients from the food. A short intestine and rectum run from the pyloric stomach to the anus at the apex of the aboral surface of the disc.[20]

Primitive starfish, such as Astropecten and Luidia, swallow their prey whole, and start to digest it in their cardial stomachs, spitting out hard material like shells. The semi-digested fluid flows into the caeca for more digestion as well as absorption.[20] In more advanced species of starfish, the cardial stomach can be everted from the organism's body to engulf and digest food, which is passed to the pyloric stomach.[21][16] The retraction and contraction of the cardial stomach is activated by a neuropeptide known as NGFFYamide.[22]

The main nitrogenous waste product is ammonia, which is removed via diffusion through the tube feet, papulae and other thin-walled areas. Other waste material include urates. The body fluid contains phagocytic cells called coelomocytes, which are also found within the hemal and water vascular systems. These cells engulf waste material, and eventually migrate to the tips of the papulae, where a portion of body wall is nipped off and ejected into the surrounding water.[23]

Starfish keep their body fluids at the same salt concentration as the surrounding water, the lack of an osmoregulation system probably explains why starfish are not found in fresh water and rarely in estuarine environments.[23]

Sensory and nervous systems

[edit]Although starfish do not have many well-defined sense organs, they do perceive touch, light, temperature, orientation and the status of the water around them. The tube feet, spines and pedicellariae are sensitive to touch. The tube feet, especially those at the tips of the rays, are also sensitive to chemicals, enabling the starfish to detect odour sources such as food.[21] There are eyespots at the ends of the arms, each one made of 80–200 simple ocelli composed of pigmented epithelial cells. Individual photoreceptor cells are present in other parts of their bodies and respond to light. Whether they advance or retreat depends on the species.[24]

While a starfish lacks a centralized brain, it has a complex nervous system with a nerve ring around the mouth and a radial nerve running along the ambulacral region of each arm parallel to the radial canal. The peripheral nerve system consists of two nerve nets: one in the epidermis and the other in the lining of the coelomic cavity, which are the sensory and motor systems respectively. Neurons passing through the dermis join the two. Both the ring and radial nerves function in movement and sensory. The sensory component is supplied with information from the sensory organs while the motor nerves control the tube feet and musculature. If one arm detects something attractive, it becomes dominant and temporarily over-rides the other arms to initiate movement towards it.[24]

Circulatory and gas exchange system

[edit]The body cavity contains the circulatory or haemal system. The vessels form three rings: one around the mouth (the hyponeural haemal ring), another around the digestive system (the gastric ring), and the third near the aboral surface (the genital ring). The heart beats about six times a minute and is at the apex of a vertical channel (the axial vessel) that connects the three rings. Blood does not contain a pigment such as heme, but is probably used to transport nutrients around the body.[23] Gas exchange mainly takes place through gills known as papulae, which are thin-walled bulges along the aboral surface of the arms. Oxygen is transferred from these to the coelomic fluid, which moves gas around the body.[14]

Secondary metabolites

[edit]Starfish produce a large number of secondary metabolites in the form of lipids, including steroidal derivatives of cholesterol, and fatty acid amides of sphingosine. The steroids are mostly saponins, known as asterosaponins, and their sulphated derivatives. They vary across species and are typically formed from up to six sugar molecules (usually glucose and galactose) connected by up to three glycosidic chains. Long-chain fatty acid amides of sphingosine occur frequently, with some having known biological activity. Starfish also contain various ceramides and a small number of alkaloids. These chemicals in the starfish may function in defence and communication. Some are feeding deterrents used by the starfish to discourage predation. Others are antifoulants and supplement the pedicellariae to prevent other organisms from settling on the starfish's aboral surface. Some are alarm pheromones and escape-eliciting chemicals, the release of which trigger responses in starfish of the same species, but often stimulate flight in potential prey.[25] Research into the efficacy of these compounds for possible pharmacological or industrial use occurs worldwide.[26]

Life cycle

[edit]Sexual reproduction

[edit]Most species of starfish are gonochorous, there being separate male and female individuals.[27] Some species are simultaneous hermaphrodites, producing eggs and sperm at the same time, and in a few of these the same gonad, called an ovotestis, produces both eggs and sperm.[28] Other starfish are sequential hermaphrodites. Protandrous individuals of species like Asterina gibbosa start life as males before changing sex into females as they grow older.[29] In some species such as Nepanthia belcheri, a large female can split in half and the resulting offspring are males. When these grow large enough they change back into females.[30]

Each starfish arm contains two gonads that release gametes through openings called gonoducts, located on the central disc between the arms. Fertilization is generally external[27] but in a few species, internal fertilization takes place.[28] In most species, the buoyant eggs and sperm are simply released into the water (free spawning) and the resulting embryos and larvae live as part of the plankton.[27] In others, the eggs may be stuck to the undersides of rocks.[29] In certain species of starfish, the females brood their eggs – either by simply enveloping them or by holding them in specialised structures in different parts of the body, externally or internally.[31][32][27] Those starfish that brood their eggs by "sitting" on them usually assume a humped posture with their discs raised off the substrate.[33][29] Pteraster militaris broods a few of its young and disperses the remaining eggs, that are too numerous to fit into its pouch.[31] In these brooding species, the eggs are relatively large, and supplied with yolk, and they generally develop directly into miniature starfish without an intervening larval stage,[28] called "lecithotrophic" .[34] In Parvulastra parvivipara, an intragonadal brooder, the young starfish obtain nutrients by eating other eggs and embryos in the brood pouch.[35] Brooding occurs in species that live in colder waters.[27] and in smaller species that produce just a few eggs.[36][37]

The timing of spawning may be influenced by lighting conditions, water temperature, food availability, and other factors. Individuals may gather together to release their gametes as once, using pheromones to attract each other.[38][37] In some species, a male and female may come together and form a pair.[39][40] They engage in pseudocopulation which involves the male crawling on the female and fertilising her gametes as she releases them.[41][37]

Larval development

[edit]

Starfish embryos typically hatch as blastulas. Invaginations take place, the first forming the anus is created from the blastopore, while a second, taking place in the ectodermic layer, creates the mouth. The archenteron stretches towards the mouth and connects with it, forming the gut.[42] A band of cilia develops on the exterior. This enlarges and extends around the surface and eventually onto two developing arm-like outgrowths. At this stage the larva is known as a bipinnaria. The cilia are used for locomotion and feeding, their rhythmic beat wafting phytoplankton towards the mouth.[8]

The next stage in development is a brachiolaria larva, and involves the growth of three short ventral-anterior arms with adhesive tips surrounding a sucker. Both bipinnaria and brachiolaria larvae are bilaterally symmetrical. When fully developed, the brachiolaria settles on the seabed and attaches itself with a short stalk made from its ventral arms and sucker. Metamorphosis now takes place with a radical rearrangement of tissues. The larvae develops an oral surface on the left and an aboral surface on the right. While the gut remains, the mouth and anus move to new positions. Some of the body cavities disappear while others become the water vascular system and the visceral coelom. The starfish is now pentaradially symmetrical. It casts off its stalk and becomes a free-living juvenile starfish up to 1 mm (0.04 in) in diameter.[8]

Asexual reproduction

[edit]

Some species of starfish can reproduce asexually as adults either by fission of their central discs or by autotomy (self-amputation) of one or more of their arms.[43][44] Single arms that regenerate a whole individual are called comet forms.[45] The larvae of several species of starfish can reproduce asexually before they reach maturity.[46] They do this by autotomising some parts of their bodies or by budding.[47] Larva increase asexual reproduction when they sense that food is plentiful.[48] Though this costs it time and energy and delays maturity, it allows a single larva to give rise to multiple adults when the conditions are appropriate.[47]

Regeneration

[edit]

Some species of starfish have the ability to regenerate lost arms and can regrow an entire new limb given time.[49] A few can regrow a complete new disc from a single arm, while others need at least part of the central disc to be attached to the detached part.[23] Regrowth can take several months, and starfish are vulnerable to infections during the early stages after the loss of an arm.[49] Other than fragmentation carried out for the purpose of reproduction, the division of the body may happen as a defense mechanism.[23] The loss of body parts is achieved by the rapid softening of a special type of connective tissue in response to nervous signals. This type of tissue is called catch connective tissue and is found in most echinoderms.[50] An autotomy-promoting factor has been identified which, when injected into another starfish, causes rapid shedding of arms.[51]

Lifespan

[edit]The lifespan of a starfish varies considerably among species. For example, Leptasterias hexactis reaches sexual maturity at 20 g (0.7 oz) in two years and lives for about ten years. Pisaster ochraceus matures at 70–90 g (2.5–3.2 oz) in five years and has a maximum recorded lifespan of 34 years.[8]

Ecology

[edit]Distribution and habitat

[edit]Starfish live in marine waters around the world including both tropical and polar waters.[6][52][53] They are mainly benthic animals, living in sandy, muddy and rocky substrates.[6][16] They range from shallow, intertidal waters[52] to the deep-sea floor down to at least 6,000 m (20,000 ft).[54] Starfish are most common along the coast.[6]

Diet

[edit]

Most species are generalist predators, eating microalgae, sponges, bivalves, snails and other small animals.[21][55] The crown-of-thorns starfish consumes coral polyps,[56] while other species are detritivores, feeding on decomposing organic material and faecal matter.[55][52] A few are suspension feeders, gathering in phytoplankton; Henricia and Echinaster often feed with sponges, taking advantage of the water current they produce. Various species can absorb organic nutrients from the surrounding water, and this may form a significant portion of their diet.[57]

The processes of feeding and capture may be aided by special parts; Pisaster brevispinus, the short-spined pisaster from the West Coast of America, can use a set of specialized tube feet to dig itself deep into the soft substrate to extract prey (usually clams).[58] Grasping the shellfish, the starfish slowly pries open the prey's shell, overcoming the clam's adductor muscle, and inserts its everted stomach into the crack to digest the soft tissues. The gap between the clam's valves need only be a fraction of a millimetre wide for the stomach to gain entry.[16]

Ecological impact

[edit]

Starfish are keystone species in their respective marine communities. Their relatively large sizes, diverse diets, and ability to adapt to different environments makes them ecologically important.[59] The term "keystone species" was in fact first used by Robert Paine in 1966 to describe a starfish, Pisaster ochraceus.[60] When studying the low intertidal coasts of Washington state, Paine found that predation by P. ochraceus was a major factor in the diversity of species. Experimental removals of this top predator from a stretch of shoreline resulted in lower species diversity and the eventual domination of Mytilus mussels, which were able to outcompete other organisms for space and resources.[61] Similar results were found in a 1971 study of Stichaster australis on the intertidal coast of the South Island of New Zealand. S. australis was found to have removed most of a batch of transplanted mussels within two or three months of their placement, while in an area from which S. australis had been removed, the mussels increased in number dramatically, overwhelming the area and threatening biodiversity.[62]

The feeding activity of the omnivorous starfish Oreaster reticulatus on sandy and seagrass bottoms near the Virgin Islands effects the composition of communities of microorganisms. These starfish engulf piles of sediment removing the surface films and algae adhering to the particles. Organisms that dislike this disturbance are replaced by others better able to rapidly recolonise "clean" sediment. In addition, foraging by these starfish creates diverse patches of organic matter, which may attract larger organisms such as fish, crabs and sea urchins that feed on the sediment.[63][64][65]

Starfish sometimes have negative effects on ecosystems. Outbreaks of crown-of-thorns starfish have caused damage to coral reefs in Northeast Australia and French Polynesia.[56][66] A study in Polynesia found that coral cover declined drastically with the arrival of migratory starfish in 2006, dropping over 40% to under 5% in four years. This in turn had a cascade effect on both sessile bottom-dwelling animals and reef fish.[56] Asterias amurensis is a rare example of an invasive echinoderm . Its larvae likely arrived in Tasmania from central Japan via water discharged from ships in the 1980s. The species has since grown in numbers to the point where they threaten important bivalve fisheries in Australia. As such, they are considered pests,[67] and are on the Invasive Species Specialist Group's list of the world's 100 worst invasive species.[68] Some species that prey on bivalve molluscs can transmit paralytic shellfish poisoning.[69]

Threats

[edit]

Starfish may be preyed on by conspecifics, sea anemones,[70] other starfish species, tritons, crabs, fish, gulls, and sea otters.[36][67][71][65] Their first lines of defence are the saponins present in their body walls, which have unpleasant flavours.[72] Some starfish such as Astropecten polyacanthus also include powerful toxins such as tetrodotoxin,[73] while the slime star can ooze out large quantities of repellent mucus.[74] The crown-of-thorns starfish possesses sharp spines, toxins and bright warning colours.[75]

Several species sometimes suffer from a wasting condition caused by Vibrio bacteria.[71] A more widespread sea star wasting disease sporadically causes mass mortalities.[76] The results of a 2025 study of starfish off the coast of central British Columbia suggest that those living in the fjords can better survive outbreaks of the disease due to the lower temperatures and higher salinity of their environment.[77][78]

The protozoan Orchitophrya stellarum is known to infect and damage the gonads of starfish.[71] Starfish are vulnerable to high temperatures. Experiments have shown that the feeding and growth rates of P. ochraceus reduce greatly when their body temperatures rise above 23 °C (73 °F) and that they die when their temperature rises to 30 °C (86 °F).[79][80][71] This species has a unique ability to absorb seawater to keep itself cool when it is exposed to sunlight by a receding tide.[81] It also appears to rely on its arms to absorb heat, so as to protect the central disc and vital organs.[82]

Starfish and other echinoderms can be vulnerable to marine pollution.[83] The common starfish is considered to be a bioindicator species for marine ecosystems.[84] A 2009 study found that P. ochraceus is unlikely to be affected by ocean acidification as severely as other marine animals with calcareous skeletons. In other groups, structures made of calcium carbonate are vulnerable to dissolution when the pH is lowered. Researchers found that when P. ochraceus were exposed to 21 °C (70 °F) and 770 ppm carbon dioxide (beyond rises expected in the next century), they were relatively unaffected. Their survival is likely due to the nodular nature of their skeletons, which are able to compensate for a shortage of carbonate by growing more fleshy tissue.[85]

Evolution

[edit]Fossil record

[edit]

The earliest fossil echinoderms date to the Cambrian, with the first asterozoans (a group that includes starfish and brittle stars) being the Somasteroidea, which exhibit traits of both groups.[86] Starfish are infrequently found as fossils, possibly because their hard skeletal components separate as the animal decays. Despite this, there are a few places where accumulations of complete skeletal structures occur, fossilized in place in Lagerstätten – so-called "starfish beds".[87]

By the late Paleozoic, the crinoids and blastoids were the predominant echinoderms, fragments of which are almost the only fossil found in some limestones. In the two major extinction events that occurred during the late Devonian and late Permian, the blastoids were wiped out and only a few species of crinoids survived.[86] Many starfish species also became extinct in these events, but afterwards the surviving few species quickly diversified rapidly over sixty million years between the beginning and middle of the Middle Jurassic.[88][89] A 2012 study found that speciation in starfish can occur rapidly. During the last 6,000 years, divergence in the larval development of Cryptasterina hystera and Cryptasterina pentagona has taken place, the former adopting internal fertilization and brooding and the latter remaining a broadcast spawner.[90]

Diversity

[edit]The scientific name Asteroidea was given to starfish by the French zoologist de Blainville in 1830.[91] It is derived from the Greek aster, ἀστήρ (a star) and the Greek eidos, εἶδος (form, likeness, appearance).[92] Starfish are included in the subphylum Asterozoa along with brittle and basket stars (order Ophiuroidea), the characteristics of which include a star-shaped body as adults, with multiple arms surrounding central disc. The arms of asteroids are skeletally connected to the disc by ossicles in the body wall[88] while ophiuroids have clearly demarcated arms.[93]

The starfish are a large and diverse class with over 1,900 living species. There are seven extant orders: Brisingida, Forcipulatida, Notomyotida, Paxillosida, Spinulosida, Valvatida and Velatida.[2][1] Living asteroids, the Neoasteroidea, are distinct from their forerunners in the Paleozoic. Their classification has changed little but there is debate in regards to Paxillosida. The deep-water sea daisies, though clearly Asteroidea and currently included in Velatida, do not fit easily in any accepted lineage. Phylogenetic data suggests that they may be a sister group, the Concentricycloidea, to the Neoasteroidea, or that the Velatida themselves may be a sister group.[89]

Living groups

[edit]- Brisingida (2 families, 17 genera, 111 species)[94]

- Species in this order have a small, rigid disc and 6–20 long, thin arms, which they use for suspension feeding. They have one series of marginal plates, disc plates merged in a ring, fewer numbers of aboral plates, crossed pedicellariae, and several series of long spines on the arms. They mostly live in deep-sea habitats, although a few live in shallow waters in the Antarctic.[95][96] In some species, the tube feet have rounded tips and lack suckers.[97]

- Forcipulatida (6 families, 63 genera, 269 species)[98]

- Species in this order have distinctive pedicellariae, consisting of a short stalk with forceps-like tips. and tube feet with flat-tipped suckers usually arranged in four rows.[97][8][88] The order includes well-known species from temperate and cold-water regions, ranging from intertidal to abyssal zones.[99]

- Notomyotida (1 family, 8 genera, 75 species)[100]

- These starfish are deep-sea dwelling and have particularly flexible arms with distinctive lines of musculature along the sides of the dorsal region.[1] In some species, the tube feet lack suckers.[97]

- Paxillosida (7 families, 48 genera, 372 species)[101]

- This is a primitive order whose members do not extrude their stomach[20] when feeding and both anus and tube feet suckers are absent.[102] Papulae are present on their aboral surface, and they possess marginal plates and paxillae. They mostly inhabit soft substrates.[8] There is no brachiolaria stage in their larval development.[102] The comb starfish (Astropecten polyacanthus) is a member of this order.[103]

- Spinulosida (1 family, 8 genera, 121 species)[104]

- Most species in this order lack pedicellariae; all have a delicate skeletal arrangement with small or no marginal plates on the disc or arms. They have numerous groups of short spines on the aboral surface.[105][106]

- Valvatida (16 families, 172 genera, 695 species)[107]

- Most species in this order have five arms and two rows of tube feet with suckers. There are conspicuous marginal plates on the arms and disc. Some species have paxillae and in some, the main pedicellariae are clamp-like and recessed into the skeletal plates.[106]

- Velatida (4 families, 16 genera, 138 species)[108]

- This order of starfish consists mostly of deep-sea and other cold-water starfish often with a global distribution. The shape is pentagonal or star-shaped with five to fifteen arms. The skeleton is underdeveloped.[109]

Extinct groups

[edit]Extinct groups within the Asteroidea include:[2]

- † Calliasterellidae, with the type genus Calliasterella from the Devonian and Carboniferous[110]

- † Palasteriscus, a Devonian genus[111]

- † Trichasteropsida, with the Triassic genus Trichasteropsis (at least 2 species)[2]

Phylogeny

[edit]External

[edit]Starfish are deuterostome animals, like the chordates. A 2014 analysis of 219 genes from all classes of echinoderms gives the following phylogenetic tree.[112] The times at which the clades diverged are shown under the labels in millions of years ago (mya).

| Bilateria |

| ||||||||||||||||||

Internal

[edit]The phylogeny of the Asteroidea has been difficult to resolve, with visible (morphological) features proving inadequate, and the question of whether traditional taxa are clades apply.[2] The phylogeny proposed by Gale in 1987 is:[2][113]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

The phylogeny proposed by Blake in 1987 is:[2][114]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Later work making use of molecular evidence, with or without the use of morphological evidence, had by 2000 failed to resolve the argument.[2] In 2011, on further molecular evidence, Janies and colleagues noted that the phylogeny of the echinoderms "has proven difficult", and that "the overall phylogeny of extant echinoderms remains sensitive to the choice of analytical methods". They presented a phylogenetic tree for the living Asteroidea only; using the traditional names of starfish orders where possible, and indicating "part of" otherwise, the phylogeny is shown below. The Solasteridae are split from the Velatida, and the old Spinulosida is broken up.[115]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Notomyotida (not analysed) | |

Human relations

[edit]In research

[edit]

Starfish have been used in reproductive and developmental studies. Female starfish produce large numbers of oocytes that are easily isolated; these can be stored in a pre-meiosis phase and stimulated to complete division by the use of 1-methyladenine.[116] Starfish oocytes are well suited for this research as they are easy to handle, can be maintained in sea water at room temperature, are transparent, and develop quickly.[117] Asterina pectinifera, used as a model organism for this purpose, is resilient and easy to breed and maintain in the laboratory.[118]

Another area of research is the ability of starfish to regenerate lost body parts. The stem cells of adult humans are incapable of much differentiation and understanding the regrowth, repair and cloning processes in starfish may have implications for human medicine.[119]

Starfish have an unusual ability to displace foreign objects from their bodies, which makes them difficult to tag for research tracking purposes.[120]

In legend and culture

[edit]

An aboriginal Australian fable, retold by the Welsh school headmaster William Jenkyn Thomas (1870–1959),[121] tells how some animals needed a canoe to cross the ocean. Whale had one but refused to lend it, so Starfish kept him busy, telling him stories and grooming him to remove parasites, while the others stole the canoe. When Whale realized the trick he beat Starfish ragged, which is how Starfish still is today.[122]

In 1900, the scholar Edward Tregear documented The Creation Song, which he describes as "an ancient prayer for the dedication of a high chief" of Hawaii. Among the "uncreated gods" described early in the song is the starfish.[123]

Georg Eberhard Rumpf's 1705 The Ambonese Curiosity Cabinet describes the tropical varieties of Stella Marina or Bintang Laut, "Sea Star" in Latin and Malay respectively, known in the waters around Ambon. He writes that the Histoire des Antilles reports that when the sea stars "see thunder storms approaching, [they] grab hold of many small stones with their little legs, looking to ... hold themselves down as if with anchors".[124]

As food

[edit]

Starfish are sometimes eaten in China,[125] Japan[126][127] and in Micronesia.[128] Georg Eberhard Rumpf found few starfish being used for food in the Indonesian archipelago, other than as bait in fish traps, but on the island of "Huamobel" [sic] the people cut them up, squeeze out the "black blood" and cook them with sour tamarind leaves; after resting the pieces for a day or two, they remove the outer skin and cook them in coconut milk.[124]

As collectables

[edit]Starfish are in some cases taken from their habitat and sold to tourists as souvenirs, ornaments, curios or for display in aquariums. In particular, Oreaster reticulatus, with its easily accessed habitat and bright coloration, is widely collected in the Caribbean. In the early to mid 20th century, this species was numerous along the West Indian coasts, but collection and trade have severely diminished its numbers. In the State of Florida, O. reticulatus is listed as endangered and its collection is illegal. Nevertheless, it is still sold both in and outside its range.[65] A similar phenomenon exists in the Indo-Pacific for species such as Protoreaster nodosus.[129]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Sweet, Elizabeth (22 November 2005). "Fossil Groups: Modern forms: Asteroids: Extant Orders of the Asteroidea". University of Bristol. Archived from the original on 14 July 2007. Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Knott, Emily (7 October 2004). "Asteroidea. Sea stars and starfishes". Tree of Life web project. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ^ Wu, Liang; Ji, Chengcheng; Wang, Sishuo; Lv, Jianhao (2012). "The advantages of the pentameral symmetry of the starfish". arXiv:1202.2219 [q-bio.PE].

- ^ Prager, Ellen (2011). Sex, Drugs, and Sea Slime: The Oceans' Oddest Creatures and Why They Matter. University of Chicago Press. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-2266-7872-6.

- ^ Lacalli, T (2023). "A radical evolutionary makeover gave echinoderms their unusual body plan". Nature. 623 (7987): 485–486. Bibcode:2023Natur.623..485L. doi:10.1038/d41586-023-03123-1.

- ^ a b c d e Ruppert et al., 2004. pp. 876–880

- ^ Sweat, L. H. (31 October 2012). "Glossary of terms: Phylum Echinodermata". Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 12 May 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f Ruppert et al, 2004. pp. 887–889

- ^ Barnes, R. S. K.; Callow, P.; Olive, P. J. W. (1988). The Invertebrates: a new synthesis. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications. pp. 158–160. ISBN 978-0-632-03125-2.

- ^ Carefoot, Tom. "Pedicellariae". Sea Stars: Predators & Defenses. A Snail's Odyssey. Archived from the original on 16 March 2013. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ^ Lawrence, J. M. (24 January 2013). "The Asteroid Arm". Starfish: Biology and Ecology of the Asteroidea. JHU Press. pp. 15–23. ISBN 978-1-4214-0787-6. in Lawrence (2013)

- ^ Fox, Richard (25 May 2007). "Asterias forbesi". Invertebrate Anatomy OnLine. Lander University. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- ^ O'Neill, P. (1989). "Structure and mechanics of starfish body wall". Journal of Experimental Biology. 147 (1): 53–89. Bibcode:1989JExpB.147...53O. doi:10.1242/jeb.147.1.53. PMID 2614339.

- ^ a b c d Ruppert et al., 2004. pp. 879–883, 889

- ^ Hennebert, E.; Santos, R.; Flammang, P. (2012). "Echinoderms don't suck: evidence against the involvement of suction in tube foot attachment" (PDF). Zoosymposia. 1: 25–32. doi:10.11646/zoosymposia.7.1.3.

- ^ a b c d Dorit, R. L.; Walker, W. F.; Barnes, R. D. (1991). Zoology. Saunders College Publishing. p. 778–782. ISBN 978-0-03-030504-7.

- ^ Cavey, Michael J.; Wood, Richard L. (1981). "Specializations for excitation-contraction coupling in the podial retractor cells of the starfish Stylasterias forreri". Cell and Tissue Research. 218 (3): 475–485. doi:10.1007/BF00210108. PMID 7196288. S2CID 21844282.

- ^ Carefoot, Tom. "Tube feet". Sea Stars: Locomotion. A Snail's Odyssey. Archived from the original on 21 October 2013. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ^ Chengcheng, J.; Wu, L.; Zhoa, W.; Wang, S.; Lv, J. (2012). "Echinoderms have bilateral tendencies". PLOS ONE. 7 (1) e28978. arXiv:1202.4214. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...728978J. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0028978. PMC 3256158. PMID 22247765.

- ^ a b c Ruppert et al., 2004. p. 885

- ^ a b c Carefoot, Tom. "Adult feeding". Sea Stars: Feeding, growth, & regeneration. A Snail's Odyssey. Archived from the original on 12 May 2013. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- ^ Semmens, Dean C.; Dane, Robyn E.; Pancholi, Mahesh R.; Slade, Susan E.; Scrivens, James H.; Elphick, Maurice R. (2013). "Discovery of a novel neurophysin-associated neuropeptide that triggers cardiac stomach contraction and retraction in starfish". Journal of Experimental Biology. 216 (21): 4047–4053. doi:10.1242/jeb.092171. PMID 23913946. S2CID 19175526.

- ^ a b c d e Ruppert et al., 2004. pp. 886–887

- ^ a b Ruppert et al., 2004. pp. 883–884

- ^ McClintock, James B.; Amsler, Charles D.; Baker, Bill J. (2013). "8: Chemistry and Ecological Role of Starfish Secondary Metabolites". In Lawrence, John M. (ed.). Starfish: Biology and Ecology of the Asteroidea. JHU Press. pp. 81–89. ISBN 978-1-4214-1045-6.

- ^ Zhang, Wen; Guo, Yue-Wei; Gu, Yucheng (2006). "Secondary metabolites from the South China Sea invertebrates: chemistry and biological activity". Current Medicinal Chemistry. 13 (17): 2041–2090. doi:10.2174/092986706777584960. PMID 16842196.

- ^ a b c d e Ruppert et al., 2004. pp. 887–888

- ^ a b c Byrne, Maria (2005). "Viviparity in the sea star Cryptasterina hystera (Asterinidae): conserved and modified features in reproduction and development". Biological Bulletin. 208 (2): 81–91. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.334.314. doi:10.2307/3593116. JSTOR 3593116. PMID 15837957. S2CID 16302535.

- ^ a b c Crump, R. G.; Emson, R. H. (1983). "The natural history, life history and ecology of the two British species of Asterina" (PDF). Field Studies. 5 (5): 867–882. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ^ Ottesen, P. O.; Lucas, J. S. (1982). "Divide or broadcast: interrelation of asexual and sexual reproduction in a population of the fissiparous hermaphroditic seastar Nepanthia belcheri (Asteroidea: Asterinidae)". Marine Biology. 69 (3): 223–233. Bibcode:1982MarBi..69..223O. doi:10.1007/BF00397488. S2CID 84885523.

- ^ a b McClary, D. J.; Mladenov, P. V. (1989). "Reproductive pattern in the brooding and broadcasting sea star Pteraster militaris". Marine Biology. 103 (4): 531–540. Bibcode:1989MarBi.103..531M. doi:10.1007/BF00399585. S2CID 84867808.

- ^ Hendler, Gordon; Franz, David R. (1982). "The biology of a brooding seastar, Leptasterias tenera, in Block Island". Biological Bulletin. 162 (3): 273–289. doi:10.2307/1540983. JSTOR 1540983.

- ^ Chia, Fu-Shiang (1966). "Brooding behavior of a six-rayed starfish, Leptasterias hexactis". Biological Bulletin. 130 (3): 304–315. doi:10.2307/1539738. JSTOR 1539738.

- ^ Lopes, E. M.; Ventura, C. R. R. (2016). "Development of the Sea Star Echinaster (Othilia) brasiliensis, with Inference on the Evolution of Development and Skeletal Plates in Asteroidea". Biological Bulletin. 230 (1): 25–34. doi:10.1086/BBLv230n1p25. PMID 26896175.

- ^ Byrne, M. (1996). "Viviparity and intragonadal cannibalism in the diminutive sea stars Patiriella vivipara and P. parvivipara (family Asterinidae)". Marine Biology. 125 (3): 551–567. Bibcode:1996MarBi.125..551B. doi:10.1007/BF00353268. S2CID 83110156.

- ^ a b Gaymer, C. F.; Himmelman, J. H. (2014). "Leptasterias polaris". Starfish: Biology and Ecology of the Asteroidea. Vol. 10. pp. 182–84. Bibcode:2014MBioR..10...93V. doi:10.1080/17451000.2013.820323. in Lawrence (2013)

- ^ a b c Mercier, A.; Hamel J-F. (2014). "Reproduction in Asteroidea". Starfish: Biology and Ecology of the Asteroidea. Vol. 10. pp. 37–38, 43, 45–48. Bibcode:2014MBioR..10...93V. doi:10.1080/17451000.2013.820323. in Lawrence (2013)

- ^ Miller, Richard L. (12 October 1989). "Evidence for the presence of sexual pheromones in free-spawning starfish". Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology. 130 (3): 205–221. Bibcode:1989JEMBE.130..205M. doi:10.1016/0022-0981(89)90164-0.

- ^ Bos A.R.; G.S. Gumanao; B. Mueller; M.M. Saceda (2013). "Size at maturation, sex differences, and pair density during the mating season of the Indo-Pacific beach star Archaster typicus (Echinodermata: Asteroidea) in the Philippines". Invertebrate Reproduction and Development. 57 (2): 113–119. Bibcode:2013InvRD..57..113B. doi:10.1080/07924259.2012.689264. S2CID 84274160.

- ^ Run, J. -Q.; Chen, C. -P.; Chang, K. -H.; Chia, F. -S. (1988). "Mating behaviour and reproductive cycle of Archaster typicus (Echinodermata: Asteroidea)". Marine Biology. 99 (2): 247–253. Bibcode:1988MarBi..99..247R. doi:10.1007/BF00391987. ISSN 0025-3162. S2CID 84566087.

- ^ Keesing, John K.; Graham, Fiona; Irvine, Tennille R.; Crossing, Ryan (2011). "Synchronous aggregated pseudo-copulation of the sea star Archaster angulatus Müller & Troschel, 1842 (Echinodermata: Asteroidea) and its reproductive cycle in south-western Australia". Marine Biology. 158 (5): 1163–1173. Bibcode:2011MarBi.158.1163K. doi:10.1007/s00227-011-1638-2. S2CID 84926100.

- ^ Ruppert et al., 2004. pp. 875

- ^ Achituv, Y.; Sher, E. (1991). "Sexual reproduction and fission in the sea star Asterina burtoni from the Mediterranean coast of Israel". Bulletin of Marine Science. 48 (3): 670–679.

- ^ Rubilar, Tamara; Pastor, Catalina; Diaz de Vivar, Enriqueta (30 January 2006). "Timing of fission in the starfish Allostichaster capensis (Echinodermata:Asteroidea) in laboratory" (PDF). Revista de Biología Tropical (53 (Supplement 3)): 299–303.

- ^ Dipper, Frances (2016). The Marine World: A Natural History of Ocean Life. Princeton University Press. p. 291. ISBN 978-0-9573946-2-9.

- ^ Eaves, Alexandra A.; Palmer, A. Richard (2003). "Reproduction: widespread cloning in echinoderm larvae". Nature. 425 (6954): 146. Bibcode:2003Natur.425..146E. doi:10.1038/425146a. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 12968170. S2CID 4430104.

- ^ a b Jaeckle, William B. (1994). "Multiple modes of asexual reproduction by tropical and subtropical sea star larvae: an unusual adaptation for genet dispersal and survival". Biological Bulletin. 186 (1): 62–71. doi:10.2307/1542036. JSTOR 1542036. PMID 29283296.

- ^ Vickery, M. S.; McClintock, J. B. (1 December 2000). "Effects of food concentration and availability on the incidence of cloning in planktotrophic larvae of the sea star Pisaster ochraceus". The Biological Bulletin. 199 (3): 298–304. doi:10.2307/1543186. JSTOR 1543186. PMID 11147710.

- ^ a b Edmondson, C. H. (1935). "Autotomy and regeneration of Hawaiian starfishes" (PDF). Bishop Museum Occasional Papers. 11 (8): 3–20.

- ^ Hayashi, Yutaka; Motokawa, Tatsuo (1986). "Effects of ionic environment on viscosity of catch connective tissue in holothurian body wall". Journal of Experimental Biology. 125 (1): 71–84. Bibcode:1986JExpB.125...71H. doi:10.1242/jeb.125.1.71. ISSN 0022-0949.

- ^ Mladenov, Philip V.; Igdoura, Suleiman; Asotra, Satish; Burke, Robert D. (1989). "Purification and partial characterization of an autotomy-promoting factor from the sea star Pycnopodia helianthoides". Biological Bulletin. 176 (2): 169–175. doi:10.2307/1541585. ISSN 0006-3185. JSTOR 1541585. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ^ a b c Turner, R. L. (2014). "Echinaster". Starfish: Biology and Ecology of the Asteroidea. Vol. 10. pp. 206–207, 210. Bibcode:2014MBioR..10...93V. doi:10.1080/17451000.2013.820323. in Lawrence (2012)

- ^ McClintock, J. G.; Pearse, J. S.; Bosch, I (1988). "Population structure and energetics of the shallow-water antarctic sea star Odontaster validus in contrasting habitats". Marine Biology. 99 (2): 235–246. Bibcode:1988MarBi..99..235M. doi:10.1007/BF00391986.

- ^ Mah, Christopher; Nizinski, Martha; Lundsten, Lonny (2010). "Phylogenetic revision of the Hippasterinae (Goniasteridae; Asteroidea): systematics of deep sea corallivores, including one new genus and three new species". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 160 (2): 266–301. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2010.00638.x.

- ^ a b Pearse, J. S. (2014). "Odontaster validus". Starfish: Biology and Ecology of the Asteroidea. Vol. 10. pp. 124–25. Bibcode:2014MBioR..10...93V. doi:10.1080/17451000.2013.820323. in Lawrence (2013)

- ^ a b c Kayal, Mohsen; Vercelloni, Julie; Lison de Loma, Thierry; Bosserelle, Pauline; Chancerelle, Yannick; Geoffroy, Sylvie; Stievenart, Céline; Michonneau, François; Penin, Lucie; Planes, Serge; Adjeroud, Mehdi (2012). Fulton, Christopher (ed.). "Predator crown-of-thorns starfish (Acanthaster planci) outbreak, mass mortality of corals, and cascading effects on reef fish and benthic communities". PLOS ONE. 7 (10) e47363. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...747363K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0047363. PMC 3466260. PMID 23056635.

- ^ Florkin, Marcel (2012). Chemical Zoology V3: Echinnodermata, Nematoda, and Acanthocephala. Elsevier. pp. 75–77. ISBN 978-0-323-14311-0.

- ^ Nybakken, James W.; Bertness, Mark D. (1997). Marine Biology: An Ecological Approach. Addison-Wesley Educational Publishers. p. 174. ISBN 978-0-8053-4582-7.

- ^ Menage, B. A.; Sanford, E. (2014). "Ecological Role of Sea Stars from Populations to Meta-ecosystems". Starfish: Biology and Ecology of the Asteroidea. Vol. 10. p. 67. Bibcode:2014MBioR..10...93V. doi:10.1080/17451000.2013.820323. in Lawrence (2013)

- ^ Wagner, S. C. (2012). "Keystone Species". Nature Education Knowledge. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- ^ Paine, R. T. (1966). "Food web complexity and species diversity". American Naturalist. 100 (190): 65–75. Bibcode:1966ANat..100...65P. doi:10.1086/282400. JSTOR 2459379. S2CID 85265656.

- ^ Paine, R. T. (1971). "A short-term experimental investigation of resource partitioning in a New Zealand rocky intertidal habitat". Ecology. 52 (6): 1096–1106. Bibcode:1971Ecol...52.1096P. doi:10.2307/1933819. JSTOR 1933819.

- ^ Scheibling, R. E. (1980). "Dynamics and feeding activity of high-density aggregations of Oreaster reticulatus (Echinodermata: Asteroidea) in a sand patch habitat". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 2: 321–27. Bibcode:1980MEPS....2..321S. doi:10.3354/meps002321.

- ^ Scheibling, R. E. (1982). "Habitat utilization and bioturbation by Oreaster reticulatus (Asteroidea) and Meoma ventricosa (Echinoidea) in a Subtidal Sand Patch". Bulletin of Marine Science. 32 (2): 624–629.

- ^ a b c Scheibling, R. E. (2014). "Oreaster reticulatus". Starfish: Biology and Ecology of the Asteroidea. Vol. 10. pp. 150–151. Bibcode:2014MBioR..10...93V. doi:10.1080/17451000.2013.820323. in Lawrence (2013)

- ^ Brodie J, Fabricius K, De'ath G, Okaji K (2005). "Are increased nutrient inputs responsible for more outbreaks of crown-of-thorns starfish? An appraisal of the evidence". Marine Pollution Bulletin. 51 (1–4): 266–78. Bibcode:2005MarPB..51..266B. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2004.10.035. PMID 15757727.

- ^ a b Byrne, M.; O'Hara, T. D.; Lawrence, J. M. (2014). "Asterias amurensis". Starfish: Biology and Ecology of the Asteroidea. Vol. 10. pp. 177–179. Bibcode:2014MBioR..10...93V. doi:10.1080/17451000.2013.820323. in Lawrence (2013)

- ^ "100 of the World's Worst Invasive Alien Species". Global Invasive Species Database. Archived from the original on 29 April 2015. Retrieved 16 July 2010.

- ^ Asakawa, M.; Nishimura, F.; Miyazawa, K.; Noguchi, T. (1997). "Occurrence of paralytic shellfish poison in the starfish Asterias amurensis in Kure Bay, Hiroshima Prefecture, Japan". Toxicon. 35 (7): 1081–1087. Bibcode:1997Txcn...35.1081A. doi:10.1016/S0041-0101(96)00216-4. PMID 9248006.

- ^ "Fact Sheet: Sea Anemones". Marine Biological Association. 21 February 2017. Archived from the original on 24 December 2019. Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- ^ a b c d Robles, C. (2014). "Pisaster ochraceus". Starfish: Biology and Ecology of the Asteroidea. Vol. 10. pp. 165–167. Bibcode:2014MBioR..10...93V. doi:10.1080/17451000.2013.820323. in Lawrence (2013)

- ^ Andersson L, Bohlin L, Iorizzi M, Riccio R, Minale L, Moreno-López W; Bohlin; Iorizzi; Riccio; Minale; Moreno-López (1989). "Biological activity of saponins and saponin-like compounds from starfish and brittle-stars". Toxicon. 27 (2): 179–88. Bibcode:1989Txcn...27..179A. doi:10.1016/0041-0101(89)90131-1. PMID 2718189.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Miyazawa, K.; Noguchi, T.; Maruyama, J.; Jeon, J. K.; Otsuka, M.; Hashimoto, K. (1985). "Occurrence of tetrodotoxin in the starfishes Astropecten polyacanthus and A. scoparius in the Seto Inland Sea". Marine Biology. 90 (1): 61–64. Bibcode:1985MarBi..90...61M. doi:10.1007/BF00428215.

- ^ "Slime star (Pteraster tesselatus)". Seastars of the Pacific Northwest. 2011. Archived from the original on 9 September 2012. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- ^ Shedd, John G. (2006). "Crown of Thorns Sea Star". Shedd Aquarium. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 22 May 2013.

- ^ Dawsoni, Solaster. "Sea Star Species Affected by Wasting Syndrome." Pacificrockyintertidal.org Seastarwasting.org (n.d.): n. pag. Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. Web.

- ^ Nono Shen (2 April 2025). "Critically endangered sunflower sea stars are seeking refuge in B.C. fiords". thecanadianpressnews.ca. The Canadian Press. Retrieved 9 April 2025.

- ^ Gehman, Alyssa-Lois Madden; Pontier, Ondine; Froese, Tyrel; VanMaanen, Derek; Blaine, Tristan; Sadlier-Brown, Gillian; Olson, Angeleen M.; Monteith, Zachary L.; Bachen, Krystal; Prentice, Carolyn; Hessing-Lewis, Margot; Jackson, Jennifer M. (2 April 2025). "Fjord oceanographic dynamics provide refuge for critically endangered Pycnopodia helianthoides". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 292 (2044) 20242770. doi:10.1098/rspb.2024.2770. PMC 11961252. PMID 40169020.

- ^ Peters, L. E.; Mouchka M. E.; Milston-Clements, R. H.; Momoda, T. S.; Menge, B. A. (2008). "Effects of environmental stress on intertidal mussels and their sea star predators". Oecologia. 156 (3): 671–680. Bibcode:2008Oecol.156..671P. doi:10.1007/s00442-008-1018-x. PMID 18347815. S2CID 19557104.

- ^ Pincebourde, S.; Sanford, E.; Helmuth, B. (2008). "Body temperature during low tide alters the feeding performance of a top intertidal predator". Limnology and Oceanography. 53 (4): 1562–1573. Bibcode:2008LimOc..53.1562P. doi:10.4319/lo.2008.53.4.1562. S2CID 1043536.

- ^ Pincebourde, S.; Sanford, E.; Helmuth, B. (2009). "An intertidal sea star adjusts thermal inertia to avoid extreme body temperatures". The American Naturalist. 174 (6): 890–897. Bibcode:2009ANat..174..890P. doi:10.1086/648065. JSTOR 10.1086/648065. PMID 19827942. S2CID 13862880.

- ^ Pincebourde, S.; Sanford, E.; Helmuth, B. (2013). "Survival and arm abscission are linked to regional heterothermy in an intertidal sea star". Journal of Experimental Biology. 216 (12): 2183–2191. Bibcode:2013JExpB.216.2183P. doi:10.1242/jeb.083881. PMID 23720798. S2CID 4514808.

- ^ Newton, L. C.; McKenzie, J. D. (1995). "Echinoderms and oil pollution: A potential stress assay using bacterial symbionts". Marine Pollution Bulletin. 31 (4–12): 453–456. Bibcode:1995MarPB..31..453N. doi:10.1016/0025-326X(95)00168-M.

- ^ Temara, A.; Skei, J.M.; Gillan, D.; Warnau, M.; Jangoux, M.; Dubois, Ph. (1998). "Validation of the asteroid Asterias rubens (Echinodermata) as a bioindicator of spatial and temporal trends of Pb, Cd, and Zn contamination in the field". Marine Environmental Research. 45 (4–5): 341–56. Bibcode:1998MarER..45..341T. doi:10.1016/S0141-1136(98)00026-9.

- ^ Gooding, Rebecca A.; Harley, Christopher D. G.; Tang, Emily (2009). "Elevated water temperature and carbon dioxide concentration increase the growth of a keystone echinoderm". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (23): 9316–9321. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.9316G. doi:10.1073/pnas.0811143106. PMC 2695056. PMID 19470464.

- ^ a b Wagonner, Ben (1994). "Echinodermata: Fossil Record". Echinodermata. The Museum of Paleontology of The University of California at Berkeley. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- ^ Benton, Michael J.; Harper, David A. T. (2013). "15. Echinoderms". Introduction to Paleobiology and the Fossil Record. Wiley. ISBN 978-1-118-68540-2.

- ^ a b c Knott, Emily (2004). "Asteroidea: Sea stars and starfishes". Tree of Life web project. Retrieved 19 October 2012.

- ^ a b Mah, Christopher L.; Blake, Daniel B. (2012). Badger, Jonathan H (ed.). "Global diversity and phylogeny of the Asteroidea (Echinodermata)". PLOS ONE. 7 (4) e35644. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...735644M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0035644. PMC 3338738. PMID 22563389.

- ^ Purit, J. B.; Keever, C. C.; Addison, J. A.; Byrne, M.; Hart, M. W.; Grosberg, R. K.; Toonen, R. J. (2012). "Extraordinarily rapid life-history divergence between Cryptasterina sea star species". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 279 (1744): 3914–3922. doi:10.1098/rspb.2012.1343. PMC 3427584. PMID 22810427.

- ^ Hansson, Hans (2013). "Asteroidea". WoRMS. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- ^ "Etymology of the Latin word Asteroidea". MyEtymology. 2008. Archived from the original on 21 October 2013. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- ^ Stöhr, S.; O'Hara, T. "World Ophiuroidea Database". Retrieved 19 October 2012.

- ^ Mah, Christopher (2012). "Brisingida". WoRMS. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ^ Downey, Maureen E. (1986). "Revision of the Atlantic Brisingida (Echinodermata: Asteroidea), with description of a new genus and family" (PDF). Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology (435). Smithsonian Institution Press: 1–57. doi:10.5479/si.00810282.435. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 February 2012. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ Mah, Christopher. "Brisingida". Access Science: Encyclopedia. McGraw-Hill. Archived from the original on 30 October 2012. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ^ a b c Vickery, Minako S.; McClintock, James B. (2000). "Comparative morphology of tube feet among the Asteroidea: phylogenetic implications". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 40 (3): 355–364. doi:10.1093/icb/40.3.355.

- ^ Mah, Christopher (2012). "Forcipulatida". WoRMS. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ^ Mah, Christopher. "Forcipulatida". Access Science: Encyclopedia. McGraw-Hill. Archived from the original on 30 October 2012. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ^ Mah, Christopher (2012). "Notomyotida". WoRMS. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ^ Mah, Christopher (2012). "Paxillosida". WoRMS. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ^ a b Matsubara, M.; Komatsu, M.; Araki, T.; Asakawa, S.; Yokobori, S.-I.; Watanabe, K.; Wada, H. (2005). "The phylogenetic status of Paxillosida (Asteroidea) based on complete mitochondrial DNA sequences". Molecular Genetics and Evolution. 36 (3): 598–605. Bibcode:2005MolPE..36..598M. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2005.03.018. PMID 15878829.

- ^ Mah, Christopher (2012). "Astropecten polyacanthus Müller & Troschel, 1842". WoRMS. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- ^ Mah, Christopher (2012). "Spinulosida". WoRMS. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ^ "Spinulosida". Access Science: Encyclopedia. McGraw-Hill. Archived from the original on 30 October 2012. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ^ a b Blake, Daniel B. (1981). "A reassessment of the sea-star orders Valvatida and Spinulosida". Journal of Natural History. 15 (3): 375–394. Bibcode:1981JNatH..15..375B. doi:10.1080/00222938100770291.

- ^ Mah, Christopher (2012). "Valvatida". WoRMS. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ^ Mah, Christopher (2012). "Velatida". WoRMS. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ^ Mah, Christopher. "Velatida". Access Science: Encyclopedia. McGraw-Hill. Archived from the original on 30 October 2012. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ^ "Family Calliasterellidae". Paleobiology Database. Archived from the original on 9 March 2016. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ^ Walker, Cyril, Ward, DavidFossils : Smithsonian Handbook, ISBN 0-7894-8984-8 (2002, paperback, revisited), ISBN 1-56458-074-1 (1992, 1st edition). Page 186

- ^ Telford, M. J.; Lowe, C. J.; Cameron, C. B.; Ortega-Martinez, O.; Aronowicz, J.; Oliveri, P.; Copley, R. R. (2014). "Phylogenomic analysis of echinoderm class relationships supports Asterozoa". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 281 (1786) 20140479. doi:10.1098/rspb.2014.0479. PMC 4046411. PMID 24850925.

- ^ Gale, A. S. (1987). "Phylogeny and classification of the Asteroidea (Echinodermata)". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 89 (2): 107–132. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1987.tb00652.x.

- ^ Blake, D. B. (1987). "A classification and phylogeny of post-Paleozoic sea stars (Asteroidea: Echinodermata)". Journal of Natural History. 21 (2): 481–528. Bibcode:1987JNatH..21..481B. doi:10.1080/00222938700771141.

- ^ Janies, Daniel A.; Voight, Janet R.; Daly, Marymegan (2011). "Echinoderm phylogeny including Xyloplax, a progenetic asteroid". Syst. Biol. 60 (4): 420–438. doi:10.1093/sysbio/syr044. PMID 21525529.

- ^ Wessel, G. M.; Reich, A. M.; Klatsky, P. C. (2010). "Use of sea stars to study basic reproductive processes". Systems Biology in Reproductive Medicine. 56 (3): 236–245. doi:10.3109/19396361003674879. PMC 3983664. PMID 20536323.

- ^ Lenart Group. "Cytoskeletal dynamics and function in oocytes". European Molecular Biology Laboratory. Archived from the original on 1 August 2014. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ^ Davydov, P. V.; Shubravyi, O. I.; Vassetzky, S. G. (1990). Animal Species for Developmental Studies: The Starfish Asterina pectinifera. Springer US. pp. 287–311. doi:10.1007/978-1-4613-0503-3. ISBN 978-1-4612-7839-9. S2CID 42046815.

- ^ Friedman, Rachel S. C.; Krause, Diane S. (2009). "Regeneration and repair: new findings in stem cell research and ageing". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1172 (1): 88–94. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04411.x. PMID 19735242. S2CID 755324.

- ^ Olsen, T. B.; Christensen, F. E. G.; Lundgreen, K.; Dunn, P. H.; Levitis, D. A. (2015). "Coelomic Transport and Clearance of Durable Foreign Bodies by Starfish (Asterias rubens)". The Biological Bulletin. 228 (2): 156–162. doi:10.1086/BBLv228n2p156. PMID 25920718.

- ^ "William Jenkyn Thomas, M.A". The Aberdare Boys' Grammar School. Archived from the original on 6 June 2014. Retrieved 12 May 2013.

- ^ Thomas, William Jenkyn (1943). Some Myths and Legends of the Australian Aborigines. Whitcombe & Tombs. pp. 21–28.

- ^ Tregear, Edward (1900). ""The Creation Song" of Hawaii". The Journal of the Polynesian Society. 9 (1): 38–46. Archived from the original on 12 February 2016. Retrieved 13 May 2013.

- ^ a b Rumphius, Georgious Everhardus (= Georg Eberhard Rumpf); Beekman, E.M. (trans.) (1999) [1705]. The Ambonese Curiosity Cabinet (original title: Amboinsche Rariteitkamer). Yale University Press. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-300-07534-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Indulging in Exotic Cuisine in Beijing". The China Guide. 2011. Archived from the original on 3 March 2014. Retrieved 28 February 2014.

- ^ Amakusa TV Co. Ltd. (7 August 2011). "Cooking Starfish in Japan". ebook10005. Amakusa TV. Retrieved 18 May 2013.

- ^ "Pouch A" (in Japanese). Kenko.com. Archived from the original on 3 August 2014. Retrieved 18 May 2013.

- ^ Johannes, Robert Earle (1981). Words of the Lagoon: Fishing and Marine Lore in the Palau District of Micronesia. University of California Press. pp. 87.

- ^ Bos, A. R.; Gumanao, G. S.; Alipoyo, J. C. E.; Cardona, L. T. (2008). "Population dynamics, reproduction and growth of the Indo-Pacific horned sea star, Protoreaster nodosus (Echinodermata; Asteroidea)". Marine Biology. 156 (1): 55–63. Bibcode:2008MarBi.156...55B. doi:10.1007/s00227-008-1064-2. hdl:2066/72067. S2CID 84521816.

Bibliography

[edit]- Lawrence, J. M., ed. (2013). Starfish: Biology and Ecology of the Asteroidea. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-1-4214-0787-6.

- Ruppert, Edward E.; Fox, Richard S.; Barnes, Robert D. (2004). Invertebrate Zoology (7th ed.). Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-81-315-0104-7.

External links

[edit]- Mah, Christopher L. (24 January 2012). "The Echinoblog". A blog about sea stars by a passionate and professional specialist.