Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

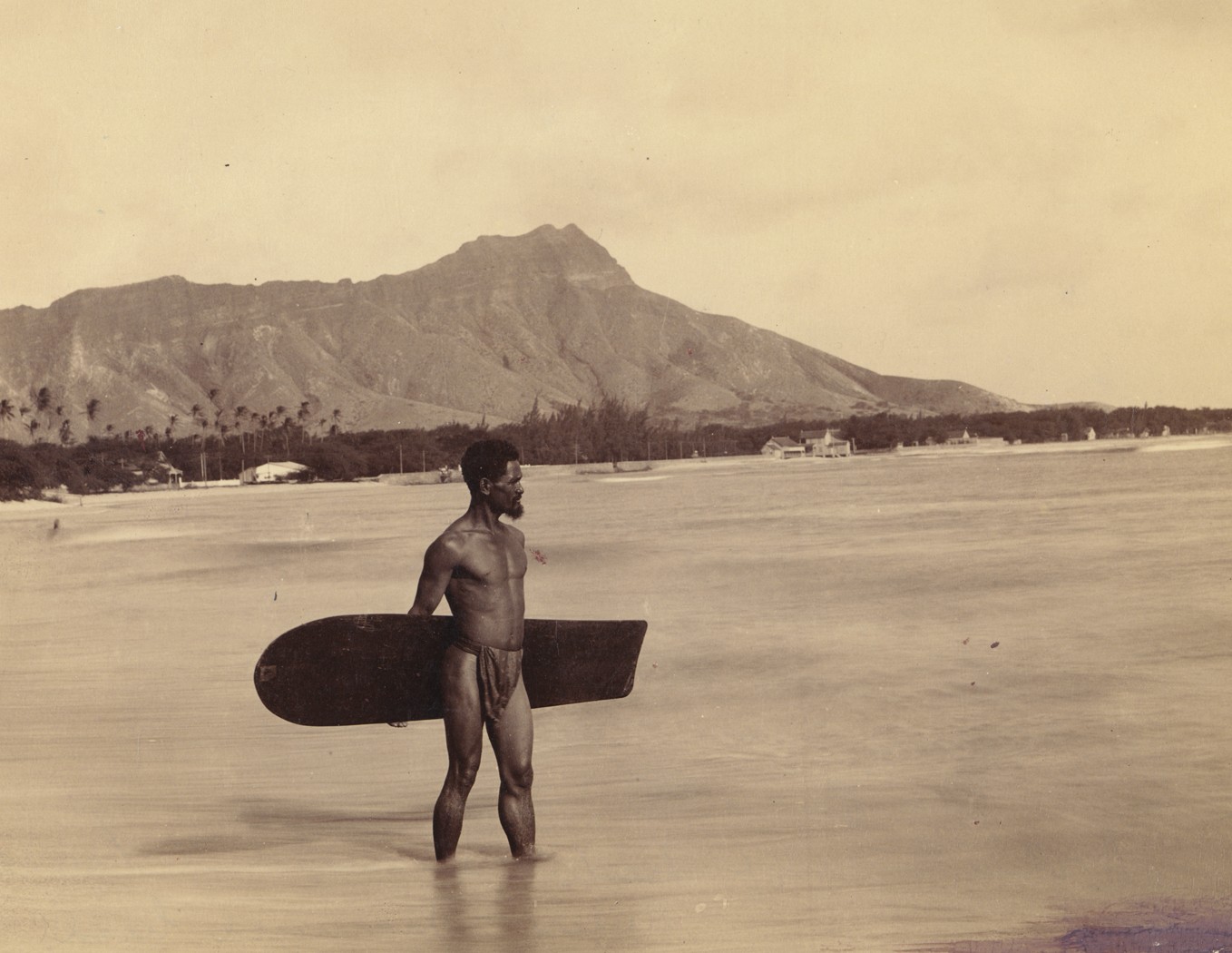

Alaia

View on Wikipedia

An alaia (pronounced /ɑːˈlaɪɑː/,[1] Hawaiian: [əˈlɐjjə]) is a thin, round-nosed, square-tailed surfboard ridden in pre-20th century Hawaii. The boards were about 200 to 350 cm (7 to 12 ft) long, weighed up to 50 kg (100 lb), and generally made from the wood of the Koa Tree.[2] They are distinct from modern surfboards in that they have no ventral fins,[1] and instead rely on the sharpness of the edges to hold the board in the face of the wave.

Modern alaias are about 150 to 350 cm (5 to 12 ft) long and are the larger version of the Paipo board, used for knee or belly surfing, and the smaller version of the Olo board, generally between 550 and 750 cm (18 and 24 ft) long. All of these board types are similar in that each is made of wood and is ridden without a sharks fin/skeg.

History

[edit]The alaia's roots span back a thousand years.[3] Lala is the Hawaiian word describing the action of riding an alaia surfboard. Lala is a word found in the Hawaiian dictionary meaning ‘the controlled slide in the curl when surfing on a board.'[4] Princess Kaʻiulani's alaia board, measuring 7ft 4in long, is preserved at the Bishop Museum.[5]

Alaia boards began making a comeback around 2006 when surfboard-shaper and experimenter Tom Wegener tested prototypes made of paulownia wood among pro-surfers.[6] The first contemporary professional surfers to master the skill of riding an alaia were documented in the Thomas Campbell surf film The Present. This appearance dramatically increased the popularity of the alaia board type.[3] Wegener used Australian surfer Jacob Stuth to test the first models, and over the next several years, he perfected the art of alaia design.

Shaper Donald Takayama furthered this movement with his designs under the Hawaiian Pro Designs label, shaped by Florida native, Brandon Russell.

Materials

[edit]“Ancient Hawaiians made their boards out of local woods–‘ulu, and koa.”[7] Modern Alaia boards are made of many types of wood, including Redwood, Cedar, Pine and Balsa. Typically, commercially sold alaia boards are made of paulownia.

Paulownia is optimal for crafting surfboards in that it has a good weight to strength ratio, being lighter than other hardwoods and more durable than balsa. It also absorbs less salt water than many other types of wood and therefore does not require a hard resin or glass finish.[3][8]

Paulownia alaia boards are most often finished with a seed oil to further prevent water absorption and to prevent damage from the drying of salt and sun associated with surfing.

Environmental impact

[edit]Many environmentalists are enthusiastic about the use of paulownia alaia boards because of their minimal impact on the environment, while fiberglass and epoxy surfboards are known for their many pollutants and long decomposition time.

Beyond avoiding fiberglass and epoxy resins, Wegener argues that modern Alaia boards have less impact on the environment based on the way the Paulownia wood is harvested, used and recycled. “Paulownia is plantation grown… The trees grow like weeds, about 25 ft (8 m) in three years and they are never from an old growth forest. Just sustainable tree farms…the leaves and flowers, is either fed to cattle or the dust and shavings are mulched… Paulownia dust (and shavings) is very good in the garden and breaks down quickly. Worms love it.”[8]

Wegener also states that paulownia is preferable over balsa regarding its impact on human health, because “balsa wood dust hurts your lungs.”[8] After construction, paulownia boards can be reshaped and repaired without use of more toxic materials. When cared for properly the boards can last a lifetime requiring less manufacturing, and when their usefulness has run out, simply discontinuing oil treatment to the board will allow it to decompose quickly without releasing harmful toxins found in foam and resin into the air and soil.[9]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Brisick, Jamie (December 4, 2009). "Ancient Surfboard Style Is Finding New Devotees". The New York Times. New York City. Archived from the original on 6 December 2009. Retrieved December 4, 2009.

- ^ Mary Kawena Pukui; Samuel Hoyt Elbert (2003). "lookup of Alaia". in Hawaiian Dictionary. Ulukau, the Hawaiian Electronic Library, University of Hawaiʻi Press. Retrieved November 17, 2010.

- ^ a b c Devon Howard (7 October 2008). "Alaia Surfboards: Design breakthrough or Passing Fad?". Surfline web site. Retrieved November 17, 2010.

- ^ "2009 Shaper of the Year: Tom Wegener | Surfing Magazine". Archived from the original on 2010-04-29. Retrieved 2010-05-11.

- ^ Clark, John R. K. (2011). Hawaiian Surfing: Traditions from the Past. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. p. 437. ISBN 978-0-8248-6032-5. OCLC 794925343.

- ^ uprock49. "Alaia Interview with Tom Wegener". commercial web site. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved April 28, 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Sumberg, Alex (January 27, 2010). "The art of crafting surfboards out of 45,000-year-old wood". Honolulu Weekly. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016.

- ^ a b c "The Greenest Board: Is Tom Wegener's Alaia the Kindest of Them All?". Surfer magazine web site. Retrieved November 17, 2010.

- ^ Tom Wegener. "Alaia". commercial web site. Archived from the original on February 17, 2011. Retrieved November 17, 2010.