Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Alquerque

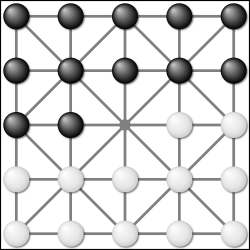

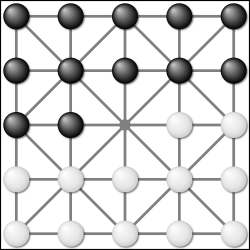

View on Wikipedia Alquerque starting position | |

| Genres | |

|---|---|

| Players | 2 |

| Setup time | ~1 minute |

| Chance | None |

| Skills | Strategy, tactics |

| Synonyms | Qirkat |

Alquerque (also known as al-qirkat from Arabic: القرقات) is a strategy board game that is thought to have originated in the Middle East. It is considered to be the parent of draughts (US: checkers) and Fanorona and the diagonals of its grid are the predecessor of the checkering of the draughts board.[citation needed]

History

[edit]

The game first appears in literature late in the 10th century when Abu al-Faraj al-Isfahani mentioned qirkat in his 24-volume work Kitab al-Aghani ("Book of Songs"). This work, however, made no direct mention of the rules of the game, most likely because it is poetry and they would have been common knowledge in the context the book originated in.

In Board and Table Games from Many Civilizations, R. C. Bell writes that "when the Moors invaded Spain they took El-quirkat with them".[1] Rules are included in Libro de los juegos ("Book of games") commissioned by Alfonso X of Castile in the 13th century.

Spanish settlers in New Mexico introduced a four-player variant of alquerque to the Zuni.

Rules

[edit]

Before starting, each player places their twelve pieces in the two rows closest to them and in the two rightmost spaces in the center row. The game is played in turns, with one player taking white and the other black.

- A piece can move from its point to any empty adjacent point that is connected by a line. Note that this is only the normal rule used at the Castilian court, as Xiangqi, Janggi, Javanese Surakarta and other, more obscure, board games allow diagonal movement without explicitly marking the relevant diagonal segment.

- A piece can jump over an opposing piece and remove it from the game, if that opposing piece is adjacent and the point beyond it is empty.

- Multiple capturing jumps are permitted, and indeed compulsory if possible.

- If a capture is possible it must be made, or else the piece is removed (or huffed).

The goal of the game is to eliminate the opponent's pieces.

Additional rules

[edit]R. C. Bell developed additional rules, saying those given by Alfonso X, in his opinion, "are not sufficient to play a game".[1] These extra rules are:

- A piece cannot move backward (e.g., a piece in the middle of an empty board would have five available moves).

- No piece can return to a point it has previously occupied.

- Once a piece has reached the opponent's back row it can only move to capture opposing pieces.

- The game is won when either:

- The opponent has lost all of their pieces.

- None of the opponent's pieces are able to move.

Bell also includes a scoring system for rating games.

See also

[edit]- Adugo

- Bagh bandi

- Bagh-chal

- Buga-shadara

- English draughts

- Fetaix

- Kharbaga

- Komikan

- Kotu Ellima

- Meurimueng-rimueng peuet ploh, tiger game played with forty

- Peralikatuma

- Permainan-Tabal

- Rimau

- Sher-bakar

- Sixteen soldiers

- Zamma

References

[edit]- ^ a b Bell, R. C. (1979). Board and Table Games from Many Civilizations, volume 1. New York City: Dover Publications. pp. 47–48. ISBN 0-486-23855-5.

External links

[edit]- An open-source Microsoft C# version of Alquerque Archived 2012-03-08 at the Wayback Machine

- Adfree Android APK version of Alquerque, minimum Android 4.4.2 (API-19)

- An open-source browser HTML5/Javascript version Alquerque, human vs AI in each combination, game rules and game options. Source: https://github.com/OMerkel/Alquerque

- Alquerque at BoardGameGeek - Alquerque rules with some sample situations discussed