Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Checkers

View on Wikipedia

| |

| Years active | at least 5,000 |

|---|---|

| Genres | |

| Players | 2 |

| Setup time | < 1 min |

| Playing time | Casual games usually last 10 to 30 minutes; tournament games last anywhere from about 60 minutes to 3 hours or more. |

| Chance | None |

| Age range | 6+ |

| Skills | Strategy, tactics |

| Synonyms |

|

Checkers[note 1] (North American English), also known as draughts (/drɑːfts, -æ-/; British English), is a group of strategy board games for two players which involve forward movements of uniform game pieces and mandatory captures by jumping over opponent pieces. Checkers is developed from alquerque.[1] The term "checkers" derives from the checkered board which the game is played on, whereas "draughts" derives from the verb "to draw" or "to move".[2]

The most popular forms of checkers in Anglophone countries are American checkers (also called English draughts), which is played on an 8×8 checkerboard; Russian draughts, Turkish draughts and Armenian draughts, all of them on an 8×8 board; and international draughts, played on a 10×10 board – with the latter widely played in many countries worldwide. There are many other variants played on 8×8 boards. Canadian checkers and Malaysian/Singaporean checkers (also locally known as dam) are played on a 12×12 board.

American checkers was weakly solved in 2007 by a team of Canadian computer scientists led by Jonathan Schaeffer. From the standard starting position, perfect play by each side will result in a draw.

General rules

[edit]Checkers is played by two opponents on opposite sides of the game board. One player has dark pieces (usually black); the other has light pieces (usually white or red). The darker color moves first, then players alternate turns. A player cannot move the opponent's pieces. A move consists of moving a piece to an adjacent unoccupied square. All pieces move forward only at the beginning of the game. At the beginning of a player's turn, if the adjacent square of a player's piece (in the player's forward direction) contains an opponent's piece, and the square immediately beyond it is vacant, the piece may be captured (must be captured in most international rules) by jumping over it.[3] The captured piece is then removed from the board.

Only the dark squares of the checkerboard are used. A piece can only move into an unoccupied square. When capturing an opponent's piece is possible, capturing is mandatory in most official rules. If the player does not capture, the other player can remove the opponent's piece as a penalty (or muffin), and where there are two or more such positions the player forfeits pieces that cannot be moved (although some rule variations make capturing optional). In almost all variants, a player with no valid move remaining loses. This occurs if the player has no pieces left, or if all the player's pieces are obstructed from moving by opponent pieces.[3]

Pieces

[edit]Man

[edit]An uncrowned piece (man) moves one step ahead and captures an adjacent opponent's piece by jumping over it and landing on the next square. Multiple enemy pieces can be captured in a single turn provided this is done by successive jumps made by a single piece; the jumps do not need to be on the same diagonal direction and may "zigzag" (change direction). In American checkers and Spanish draughts, men can jump only forwards; in international draughts and Russian draughts, men can jump both forwards and backwards.

King

[edit]

When a man reaches the farthest row forward, known as the kings row or crown head, it becomes a king. It is marked by placing an additional piece on top of, or crowning, the first man. The king has additional powers, namely the ability to move any amount of squares at a time (in international checkers), move backwards and, in variants where men cannot already do so, capture backwards. Like a man, a king can make successive jumps in a single turn, provided that each jump captures an enemy piece.

In international draughts, kings can move any number of squares, forward or backward. Kings with such an ability are also informally called flying kings. They may capture an opposing man, regardless of distance, by jumping to any of the unoccupied squares immediately past the man. Because jumped pieces remain on the board until the turn is completed, it is possible to reach a position in a multi-jump move where the flying king is blocked from capturing further by a piece already jumped.

Flying kings are not used in American checkers; a king's only advantage over a man is the additional ability to move and capture backwards.

Naming

[edit]In most non-English languages (except those that acquired the game from English speakers), checkers is called dame, dames, damas, or a similar term that refers to ladies. The pieces are usually called men, stones, "peón" (pawn) or a similar term; men promoted to kings are called dames or ladies. In these languages, the queen in chess or in card games is usually called by the same term as the kings in checkers. A case in point includes the Greek terminology, in which checkers is called "ντάμα" (dama), which is also one term for the queen in chess.[citation needed]

History

[edit]Ancient games

[edit]

Similar games have been played for millennia.[2] A board resembling a checkers board was found in Ur dating from 3000 BC.[4] In the British Museum are specimens of ancient Egyptian checkerboards, found with their pieces in burial chambers, and the game was played by the pharaoh Hatshepsut.[2][5] Plato mentioned a game, πεττεία or petteia, as being of Egyptian origin,[5] and Homer also mentions it.[5] The method of capture was placing two pieces on either side of the opponent's piece. It was said to have been played during the Trojan War.[6][7] The Romans played a derivation of petteia called latrunculi, or the game of the Little Soldiers. The pieces, and sporadically the game itself, were called calculi (pebbles).[5][8] Like the pawn in chess, alquerque was probably derived from πεττεία and latrunculi by removing the necessity for two pieces to cooperate to capture one, although, like Ghanaian draughts, the game could still be declared lost by a player with only one piece left.

Alquerque

[edit]

An Arabic game called Quirkat or al-qirq, with similar play to modern checkers, was played on a 5×5 board. It is mentioned in the tenth-century work Kitab al-Aghani.[4] Al qirq was also the name for the game that is now called nine men's morris.[9] Al qirq was brought to Spain by the Moors,[10] where it became known as Alquerque, the Spanish derivation of the Arabic name. It was maybe a derivation of latrunculi, or the game of the Little Soldiers, with a leaping capture, which could, like modern Argentine, German, Greek, Kenyan and Thai draughts, have flying kings which had to stop on the next square after the captured piece, which is just one step long of the displacement capture of backgammon and chess and its variants, but pieces could only make up to three captures at once, or seven if all directions were legal, or pieces had to change directions in the course of a multiple capture. That said, even if playing al qirq inside the cells of a square grid was not already known to the Moors who brought it, which it probably was, either via playing on a chessboard (in about 1100, probably in the south of France, this was done once again using backgammon pieces,[11] thereby each piece was called a "fers", the same name as the chess queen, as the move of the two pieces was the same at the time)[12] or adapting Seega using jumping capture. The rules are given in the 13th-century book Libro de los juegos.[4]

Crowning

[edit]The rule of crowning was used by the 13th century, as it is mentioned in the Philippe Mouskés's Chronique in 1243[4] when the game was known as Fierges, the name used for the chess queen (derived from the Persian ferz, meaning royal counsellor or vizier). The pieces became known as "dames" when that name was also adopted for the chess queen.[12] The rule forcing players to take whenever possible was introduced in France in around 1535, at which point the game became known as Jeu forcé, identical to modern American checkers.[4][13] The game without forced capture became known as Le jeu plaisant de dames, the precursor of international checkers.

The 18th-century English author Samuel Johnson wrote a foreword to a 1756 book about checkers by William Payne, the earliest book in English about the game.[5]

Invented variants

[edit]

- Blue and Gray: On a 9×9 board, each side has 17 guard pieces that move and jump in any direction, to escort a captain piece which races to the centre of the board to win.[14]

- Cheskers: A variant invented by Solomon Golomb. Each player begins with a bishop and a camel (which jumps with coordinates (3,1) rather than (2,1) so as to stay on the black squares), and men reaching the back rank promote to a bishop, camel, or king.[15][16]

- Damath: A variant utilizing math principles and numbered chips popular in the Philippines.[17]

- Dameo: A variant played on an 8×8 board that utilizes all 64 squares and has diagonal and orthogonal movement. A special "sliding" move is used for moving a line of checkers similar to the movement rule in Epaminondas. By Christian Freeling (2000).[18][19][20]

- Hexdame: A literal adaptation of international draughts to a hexagonal gameboard. By Christian Freeling (1979).[21]

- Lasca: A checkers variant on a 7×7 board, with 25 fields used. Jumped pieces are placed under the jumper, so that towers are built. Only the top piece of a jumped tower is captured. This variant was invented by World Chess Champion Emanuel Lasker.[22]

- Loca: A checkers variant with pieces, including men, that move short but capture long. By Christian Freeling (2020).

- Philosophy shogi checkers: A variant on a 9×9 board, game ending with capturing opponent's king. Invented by Inoue Enryō and described in Japanese book in 1890.[23]

- Suicide checkers (also called Anti-Checkers, Giveaway Checkers or Losing Draughts): A variant where the objective of each player is to lose all of their pieces.[24][25]

Computer checkers

[edit]

American checkers has been the arena for several notable advances in game artificial intelligence. In 1951 Christopher Strachey created Checkers, a simulation of the board game. The checkers game tried to run for the first time on 30 July 1951 at NPL, but was unsuccessful due to program errors. In the summer of 1952 he successfully ran the program on Ferranti Mark 1 computer and played the first computer checkers and one of the first video games according to many definitions. In the 1950s, Arthur Samuel created one of the first board game-playing programs of any kind. More recently, in 2007 scientists at the University of Alberta[26] developed their "Chinook" program to the point where it is unbeatable. A brute force approach that took hundreds of computers working nearly two decades was used to solve the game,[27] showing that a game of checkers will always end in a draw if neither player makes a mistake.[28][29] The solution is for the checkers variation called go-as-you-please (GAYP) checkers and not for the variation called three-move restriction checkers, however it is a legal three-move restriction game because only openings believed to lose are barred under the three-move restriction. As of December 2007, this makes American checkers the most complex game ever solved.

In November 1983, the Science Museum Oklahoma (then called the Omniplex) unveiled a new exhibit: Lefty the Checker Playing Robot. Programmed by Scott M Savage, Lefty used an Armdroid robotic arm by Colne Robotics and was powered by a 6502 processor with a combination of Basic and Assembly code to interactively play a round of checkers with visitors to the museum. Originally, the program was deliberately simple so that the average museum visitor could potentially win, but over time was improved. The improvements however proved to be more frustrating for the visitors, so the original code was reimplemented.[30]

Computational complexity

[edit]Generalized Checkers is played on an M × N board.

It is PSPACE-hard to determine whether a specified player has a winning strategy. And if a polynomial bound is placed on the number of moves that are allowed in between jumps (which is a reasonable generalisation of the drawing rule in standard Checkers), then the problem is in PSPACE, thus it is PSPACE-complete.[31] However, without this bound, Checkers is EXPTIME-complete.[32]

However, other problems have only polynomial complexity:[31]

- Can one player remove all the other player's pieces in one move (by several jumps)?

- Can one player king a piece in one move?

National and regional variants

[edit]-

10×10 board, starting position in international draughts

-

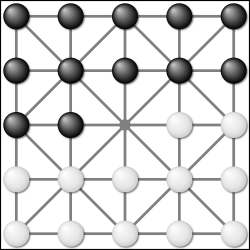

8×8 board, starting position in English, Brazilian, Czech and Russian draughts, as well as Pool checkers

-

12×12 board, starting position in Canadian draughts

-

8×8 board, starting position in Turkish and Armenian draughts

-

8×8 board, starting position in Italian and Portuguese draughts

-

8×8 board, starting position and example play in Bashni

Flying kings; men can capture backwards

[edit]| National variant | Board size | Pieces per side | Double-corner or light square on player's near-right? | First move | Capture constraints | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| International draughts (or Polish draughts) | 10×10 | 20 (originally, 15) |

Yes | White | A sequence must capture the maximum possible number of pieces. | Pieces promote only when ending their move on the final rank, not when passing through it. It is mainly played in the Netherlands, Suriname, France, Belgium, some eastern European countries, some parts of Africa, some parts of the former USSR, and other European countries. |

| Ghanaian draughts (or damii) | 10×10 | 20 | No[33] | White | Any sequence may be chosen, as long as all possible captures are made. Overlooking a king's capture opportunity leads to forfeiture of the king. | Played in Ghana. Having only a single piece remaining (man or king) loses the game. It is similar to 10×10 Czech Draughts, but has backwards capture and allows winning by removing all but one piece, similar to Latrunculi. |

| Frisian draughts | 10×10 | 20 | Yes | White | A sequence of capture must give the maximum "value" to the capture, and a king (called a wolf) has a value of less than two men but more than one man. If a sequence with a capturing wolf and a sequence with a capturing man have the same value, the wolf must capture. The main difference with the other games is that the captures can be made diagonally, but also straight forwards and sideways. | Played primarily in Friesland (Dutch province) historically, but in the last decade spreading rapidly over Europe (e.g. the Netherlands, Belgium, Italy, Czech Republic, Ukraine and Russia) and Africa, as a result of a number of recent international tournaments and the availability of an iOS and Android app "Frisian Draughts". Also most likely a descendant of German Englisch and Swedish Engelska via Swedish Marquere and Danish Makvar/Makvær. |

| Canadian checkers | 12×12 | 30 | Yes | White | A sequence must capture the maximum possible number of pieces. | International rules on a 12×12 board. Played mainly in Canada. |

| South African draughts | 14×14 | 42 | Yes | White | A sequence must capture the maximum possible number of pieces. | International rules on a 14×14 board. Played mainly in South Africa. |

| Brazilian draughts (or damas) (or Minor Polish draughts) | 8×8 | 12 | Yes | White | A sequence must capture the maximum possible number of pieces. | Played in Brazil. The rules come from international draughts, but board size and number of pieces come from American checkers. |

| Filipino Checkers (or dama) | 8×8 | 12 | Two variations exist: one with the double-corner on player's near-right and the other on player's near-left. | White | A sequence must capture the maximum possible number of pieces. | Played in the Philippines. Similar to Brazilian Draughts but with some specifics. Usually played on a dama matrix (crossed lined board representing only the diagonals) and comes in two orientations. |

| Pool checkers | 8×8 | 12 | Yes | Black | Any sequence may be chosen, as long as all possible captures are made. | Also called Spanish Pool checkers. It is mainly played in the southeastern United States; traditional among African American players. A man reaching the kings row is promoted only if he does not have additional backwards jumps (as in international draughts).[1][2]

In an ending with three kings versus one king, the player with three kings must win in thirteen moves or the game is a draw. |

| Jamaican draughts/checkers | 8×8 | 12 | No | Black | Any sequence may be chosen, as long as all possible captures are made. | Similar to Pool checkers with the exception of the main diagonal on the right instead of the left. A man reaching the kings row is promoted only if he does not have additional backwards jumps (as in international draughts).

In an ending with three kings versus one king, the player with three kings must win in thirteen moves or the game is a draw. |

| Russian draughts | 8×8 | 12 | Yes | White | Any sequence may be chosen, as long as all possible captures are made. | Also called shashki or Russian shashki checkers. It is mainly played in the former USSR and in Israel. Rules are similar to international draughts, except:

There is also a 10×8 board variant (with two additional columns labelled i and k)[34] and the give-away variant Poddavki. There are official championships for shashki and its variants. |

| Mozambican draughts/checkers | 8×8 | 12 | No | White | A sequence must capture the maximum possible number of pieces. Although, a king has the weight of two pieces, this means with two captures, one of a king and one of a piece, one must choose the king; two captures, one of a king and one of two pieces, the player can choose; two captures with one of a king and one of three pieces, the player must capture the three pieces; two captures, one of two kings and one of three pieces, one must choose the kings... | Also called "Dama" or "Damas". It is played along all of the region of Mozambique. In an ending with three kings versus one king, the player with three kings must win in thirteen moves or the game is a draw. |

| Kenyan checkers | 8×8 | 12 | Yes | White | Any sequence may be chosen, as long as all possible captures are made. | Kings (must capture in order to move multiple squares and) when they capture, must stop directly after the captured piece, and may begin a new capture movement from there.

With this rule, there is no draw with two kings versus one, or even one versus one if the kings must capture in order to move multiple squares. |

| Tobit | 6×4 grid |

12 | — | White | Mandatory Capture and Maximum Capture | Played on a unique non-rectangular or square board of grids with 20 grid points and 18 endpoints. Played in the Republic of Khakassia. Movement and capture is orthogonal with backwards capture. The "Tobit," a promoted piece, moves like the King in Turkish draughts. |

| Keny | 8×8 | 16 | — | Variable; Most rules have mandatory capture without maximum capture | Keny (Russian: Кены) is a draughts game played in the Caucasus and nearby areas of Turkey. It is played on an 8×8 grid with orthogonal movement. It is similar to Turkish Draughts, but has backwards capture and allows for men to jump over friendly pieces without capturing them similar to Dameo. |

Flying kings; men cannot capture backwards

[edit]| National variant | Board size | Pieces per side | Double-corner or light square on player's near-right? | First move | Capture constraints | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spanish draughts | 8×8 | 12 | Light square is on right, but double corner is on left, as play is on the light squares. (Play on the dark squares with dark square on right is Portuguese draughts.) | White | A sequence must capture the maximum possible number of pieces, and the maximum possible number of kings from all such sequences. | Also called Spanish checkers. It is mainly played in Portugal, some parts of South America, and some Northern African countries. |

| Argentinian draughts | 8×8 10×10 |

12 15 |

No | White | The rules are similar to the Spanish game, but a sequence that the king can capture must be captured first of all sequences of the same number of pieces.[3] | The rules are similar to the Spanish game, but the king, when it captures, must stop directly after the captured piece, and may begin a new capture movement from there.

With this rule, there is no draw with two kings versus one. |

| Malaysian/Singaporean checkers | 12×12 | 30 | Yes | Not fixed | Captures are mandatory. Failing to capture results in forfeiture of that piece (huffing). | Mainly played in Malaysia, Singapore, and the region nearby. Also known locally as "Black–White Chess". Sometimes it is played on an 8×8 board when a 12×12 board is unavailable; a 10×10 board is rare in this region. |

| Czech draughts | 8×8 10×10 |

12 15 |

Yes | White | If there are sequences of captures with either a man or a king, the king must be chosen. After that, any sequence may be chosen, as long as all possible captures are made. | This variant is from the family of the Spanish game. Slovak variant is occasionally mislabeled as Hungarian |

| Hungarian Highlander draughts | 8×8 | 8 | White | All pieces are long-range. Jumping is mandatory after first move of the rook. Any sequence may be chosen, as long as all possible captures are made. | The uppermost symbol of the cube determines its value, which is decreased after being jumped. Having only one piece remaining loses the game. | |

| Thai draughts | 8×8 | 8 | Yes | Black | Any sequence may be chosen, as long as all possible captures are made. | During a capturing move, pieces are removed immediately after capture. Kings stop on the square directly behind the piece captured and must continue capturing from there, if possible, even in the direction where they come from. |

| German draughts (or Dame) | 8×8 | 12 | Yes | Black | Any sequence may be chosen, as long as all possible captures are made. In Germany, pieces may further be required to take the longest sequence. | Kings stop on the square directly behind the piece captured and must continue capturing from there as long as possible.

Though called German, it is actually popular not so much in Northern Germany, but in Denmark and Finland. |

| Turkish draughts | 8×8 | 16 | — | White | A sequence must capture the maximum possible number of pieces. Captured pieces are removed immediately so that a sequence may even continue in the direction where the capturing piece comes from | Also known as Dama. Men move straight forwards or sideways, instead of diagonally. When a man reaches the last row, it is promoted to a flying king (Dama), which moves like a rook (or a queen in the Armenian variant). The pieces start on the second and third rows.

It is played in Turkey, Kuwait, Israel, Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Greece, and several other locations in the Middle East, as well as in the same locations as Russian checkers. There are several variants in these countries, with the Armenian variant (called tama) allowing also forward-diagonal movement of men and the Greek requiring the king to stop directly after the captured piece. With this rule, there is no draw with one king and men versus one king. |

| Myanmar draughts | 8×8 | 12 | White | A sequence must capture the maximum possible number of pieces. | Players agree before starting the game between "Must Capture" or "Free Capture". In the "Must Capture" type of game, a man that fails to capture is forfeited (huffed). In the "Free Capture" game, capturing is optional. | |

| Tanzanian draughts | 8×8 | 12 | Yes | Not fixed | Any sequence may be chosen, as long as all possible captures are made. |

No flying kings; men cannot capture backwards

[edit]| National variant | Board size | Pieces per side | Double-corner or light square on player's near-right? | First move | Capture constraints | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| American checkers | 8×8 10×10 |

12 15 20 |

Yes | Black | Any sequence may be chosen, as long as all possible captures are made. | Also called "straight checkers" in the United States, or "English draughts" in the United Kingdom. |

| Italian draughts | 8×8 10×10 |

12 15 20 |

No | White | Men cannot jump kings. A sequence must capture the maximum possible number of pieces. If more than one sequence qualifies, the capture must be done with a king instead of a man. If more than one sequence qualifies, the one that captures a greater number of kings must be chosen. If there are still more sequences, the one that captures a king first must be chosen. | It is mainly played in Italy and some North African countries. Old French draughts is the same game without the obligation to jump kings with a king. Thus it was most likely first played in the Piedmont and the Aosta Valley, near the French border.

This is possibly the same game as the Marella that Pietro Carrera mentions in passing in his Il Gioco degli scacchi (1617),[35] notwithstanding a strange earlier reference to a Smarella played on an 8x6 checkered board with 12 pieces on a side.[36] |

| Gothic checkers (or Altdeutsches Damespiel or Altdeutsche Dame) | 8×8 | 16 | — | White | Captures are mandatory. | All 64 squares are used, dark and light. Men move one cell diagonally forward and capture in any of the five cells directly forward, diagonally forward, or sideways, but not backward. Men promote on the last row. Kings may move and attack in any of the eight directions. There is also a variant with flying kings. |

Russian Column draughts

[edit]Column draughts (Russian towers), also known as Bashni, is a kind of draughts, known in Russia since the beginning of the nineteenth century, in which the game is played according to the usual rules of Russian draughts, but with the difference that the captured man is not removed from the playing field: rather, it is placed under the capturing piece (man or tower).

The resulting towers move around the board as a whole, "obeying" the upper piece. When taking a tower, only the uppermost piece is removed from it: and the resulting tower belongs to one player or the other according to the color of its new uppermost piece.

Championships

[edit]- World Checkers/Draughts Championship in American checkers since 1840

- Draughts World Championship in international draughts since 1885

- Women's World Draughts Championship in international draughts since 1873

- Draughts-64 World Championships since 1985

Federations

[edit]- World Draughts Federation (FMJD) was founded in 1947 by four Federations: France, the Netherlands, Belgium and Switzerland.[37]

- International Draughts Federation (IDF) was established in 2012 in Bulgaria.[38]

Games sometimes confused with checkers variants

[edit]- Halma: A game in which pieces move in any direction and jump over any other piece, friend or enemy (but with no captures), and players try to move them all into an opposite corner.

- Chinese checkers: Based on Halma, but uses a star-shaped board divided into equilateral triangles.

- Kōnane: "Hawaiian checkers".

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ When this word is used in the UK, it is usually spelled chequers (as in Chinese chequers) when referring to the pattern of the checker board; see further at American and British spelling differences.

References

[edit]- ^ "Draughts / Checkers and the Alquerque Family". TradGames. James Masters. Retrieved 17 January 2025.

- ^ a b c Strutt, Joseph (1801). The sports and pastimes of the people of England. London. p. 255.

- ^ a b "How to Play Checkers: A Beginner's Guide to Mastering Strategy and Fun". foony.com. Retrieved 17 April 2025.

- ^ a b c d e Oxland, Kevin (2004). Gameplay and design (Illustrated ed.). Pearson Education. p. 333. ISBN 978-0-321-20467-7.

- ^ a b c d e "Lure of checkers". The Ellensburgh Capital. 17 February 1916. p. 1. Retrieved 16 April 2009.

- ^ "Petteia". 9 December 2006. Archived from the original on 9 December 2006.

- ^ Austin, Roland G. (September 1940). "Greek Board Games". Antiquity. 14 (55). University of Liverpool, England: 257–271. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00015258. S2CID 163535077. Archived from the original on 8 April 2009. Retrieved 16 April 2009.

- ^ Peck, Harry Thurston (1898). "Latruncŭli". Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities. New York: Harper and Brothers. Archived from the original on 8 October 2008. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ^ Berger, F (2004). "From circle and square to the image of the world: a possible interpretation or some petroglyphs of merels boards" (PDF). Rock Art Research. 21 (1): 11–25. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 November 2004.

- ^ Bell, R. C. (1979). Board and Table Games from Many Civilizations. Vol. I. New York City: Dover Publications. pp. 47–48. ISBN 0-486-23855-5.

- ^ Bell, Robert Charles (1981). Board and Table Game Antiques (2000 ed.). Shire Books. p. 13. ISBN 0-85263-538-9.

- ^ a b Murray, H. J. R. (1985) [First pub. 1913 by Oxford University Press]. A History of Chess. Benjamin Press. ISBN 0-936317-01-9. OCLC 13472872.

- ^ Bell, Robert Charles (1981). Board and Table Game Antiques (Illustrated ed.). Osprey Publishing. p. 33. ISBN 0-85263-538-9.

- ^ Sackson, Sid (1982) [1st Pub. 1969, Random House, New York]. "Blue and Gray". A Gamut of Games. Pantheon Books. pp. 9, 10–11. ISBN 0-394-71115-7 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Cheskers". www.chessvariants.org. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- ^ Pritchard, D. Brine (1994). The encyclopedia of chess variants. Godalming: Games & Puzzles. ISBN 0-9524142-0-1. OCLC 60113912.

- ^ "DepEd promotes 'Damath'". Philstar.com.

- ^ "Rules". www.mindsports.nl. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ Tapalnitski, Aleh (2019). Meet Dameo (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 October 2020.

- ^ Freeling, Christian (14 April 2021). "Dameo" (PDF). Abstract Games... For the Competitive Thinker. 10 Summer 2002: 10–12.

- ^ Kok, Fred (Winter 2001). Kerry Handscomb (ed.). "Hexdame • A nice combination". Abstract Games. No. 8. Carpe Diem Publishing. p. 21. ISSN 1492-0492.

- ^ Angerstein, Wolfgang. Board Game Studies: Das Säulenspiel Laska: Renaissance einer fast vergessenen Dame-Variante mit Verbindungen zum Schach. Vol. 5, CNWS Publications, 2002, pp. 79-99, bgsj.ludus-opuscula.org/PDF_Files/BGS5-complete.pdf. Archived 2 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 16 Dec. 2021.

- ^ "近代デジタルライブラリー - 哲学将碁哲学飛将碁指南". archive.ph. 19 December 2012. Archived from the original on 19 December 2012. Retrieved 19 October 2024.

- ^ "ФШР | Обратные шашки (поддавки)". Федерация шашек России (in Russian). Retrieved 16 December 2021.

- ^ в 18:13, Ольга Ворончихина 27/10/2012. "Поддавки - Первый Чемпионат по игре в обратные шашки | Шашки всем". Retrieved 16 December 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Chinook - World Man-Machine Checkers Champion Archived 24 June 2003 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Schaeffer, Jonathan; Burch, Neil; Björnsson, Yngvi; Kishimoto, Akihiro; Müller, Martin; Lake, Robert; Lu, Paul; Sutphen, Steve (14 September 2007). "Checkers Is Solved". Science. 317 (5844): 1518–1522. Bibcode:2007Sci...317.1518S. doi:10.1126/science.1144079. PMID 17641166. S2CID 10274228.

- ^ Jonathan Schaeffer, Yngvi Bjornsson, Neil Burch, Akihiro Kishimoto, Martin Muller, Rob Lake, Paul Lu and Steve Sutphen. Solving Checkers, International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI), pp. 292–297, 2005. Distinguished Paper Prize

- ^ "Chinook - Solving Checkers Publications". www.cs.ualberta.ca. Archived from the original on 16 April 2008. Retrieved 22 December 2007.

- ^ "But Can It Type". The Daily Oklahoman. The Daily Oklahoman. 25 November 1983. p. 51. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- ^ a b Fraenkel, Aviezri S.; Garey, M. R.; Johnson, David S.; Yesha, Yaacov (1978). "The complexity of checkers on an N × N board". 19th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science. pp. 55–64. doi:10.1109/SFCS.1978.36.

- ^ Robson, J. M. (May 1984). "N by N Checkers is EXPTIME complete". SIAM Journal on Computing. 13 (2): 252–267. doi:10.1137/0213018.

- ^ Salm, Steven J.; Falola, Toyin (2002). Culture and Customs of Ghana. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-0-313-32050-7.

- ^ Similar to Capablanca chess, likely to have emerged as a way of speeding up the original 10x10 game.

- ^ “quel gioco, che i siciliani chiamano marella, e gli spagnuoli el juego de las damas” (p.35, “That game that the Sicilians call marella and the Spaniards el juego de las damas”)

- ^ Tescanella, Oratio (1567). L'institutioni oratorie di Quintiliano (in Italian).

- ^ "FMJD - World Draughts Federation".

- ^ "IDF | IDF | International Draughts Federation".

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Draughts". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 8 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 547–550.

External links

[edit]Draughts associations and federations

- American Checker Federation (ACF)

- American Pool Checkers Association (APCA)

- Danish Draughts Federation

- English Draughts Association (EDA)

- European Draughts Confederation

- German Draughts Association (DSV NRW) Archived 27 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Northwest Draughts Federation (NWDF)

- Polish Draughts Federation (PDF)

- Surinam Draughts Federation (SDB)

- World Checkers & Draughts Federation Archived 10 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- World Draughts Federation (FMJD)

- The International Draughts Committee of the Disabled (IDCD) Archived 14 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine

History, articles, variants, rules

- A Guide to Checkers Families and Rules by Sultan Ratrout

- The history of checkers/draughts

- Jim Loy's checkers pages with many links and articles.

- Checkers Maven, CheckersUSA checkers books, electronic editions

- The Checkers Family

- Alemanni Checkers Pages

- On the evolution of Draughts variants

- "Chess and Draughts/Checkers" by Edward Winter

Online play

- mindoku.com Play online draughts, Russian draughts or giveaway draughts. Online tournaments every day.

- Server for playing correspondence tournaments

- A free program that allows you to play more than 20 kinds of draughts

- A free application that allows you to play 15 popular checkers variants with a human or a computer

- Draughts.org Play online draughts plus information on strategies and history.

- Lidraughts.org Internet draughts server, similar to the popular chess server lichess.org