Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

India

View on Wikipedia

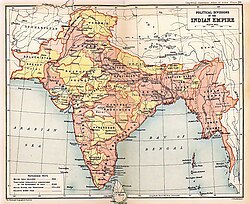

India, officially the Republic of India,[j][20] is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area; the most populous country since 2023;[21] and, since its independence in 1947, the world's most populous democracy.[22][23][24] Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the south, the Arabian Sea on the southwest, and the Bay of Bengal on the southeast, it shares land borders with Pakistan to the west;[k] China, Nepal, and Bhutan to the north; and Bangladesh and Myanmar to the east. In the Indian Ocean, India is near Sri Lanka and the Maldives; its Andaman and Nicobar Islands share a maritime border with Myanmar, Thailand, and Indonesia.

Key Information

Modern humans arrived on the Indian subcontinent from Africa no later than 55,000 years ago.[26][27][28] Their long occupation, predominantly in isolation as hunter-gatherers, has made the region highly diverse.[29] Settled life emerged on the subcontinent in the western margins of the Indus river basin 9,000 years ago, evolving gradually into the Indus Valley Civilisation of the third millennium BCE.[30] By 1200 BC, an archaic form of Sanskrit, an Indo-European language, had diffused into India from the northwest.[31][32] Its hymns recorded the early dawnings of Hinduism in India.[33] India's pre-existing Dravidian languages were supplanted in the northern regions.[34] By 400 BC, caste had emerged within Hinduism,[35] and Buddhism and Jainism had arisen, proclaiming social orders unlinked to heredity.[36] Early political consolidations gave rise to the loose-knit Maurya and Gupta Empires.[37] Widespread creativity suffused this era,[38] but the status of women declined,[39] and untouchability became an organised belief.[l][40] In South India, the Middle kingdoms exported Dravidian language scripts and religious cultures to the kingdoms of Southeast Asia.[41]

In the early medieval era, Christianity, Islam, Judaism, and Zoroastrianism became established on India's southern and western coasts.[42] Muslim armies from Central Asia intermittently overran India's northern plains in the second millennium.[43] The resulting Delhi Sultanate drew northern India into the cosmopolitan networks of medieval Islam.[44] In south India, the Vijayanagara Empire created a long-lasting composite Hindu culture.[45] In the Punjab, Sikhism emerged, rejecting institutionalised religion.[46] The Mughal Empire ushered in two centuries of economic expansion and relative peace,[47] leaving a rich architectural legacy.[48][49] Gradually expanding rule of the British East India Company turned India into a colonial economy but consolidated its sovereignty.[50] British Crown rule began in 1858. The rights promised to Indians were granted slowly,[51][52] but technological changes were introduced, and modern ideas of education and the public life took root.[53] A nationalist movement emerged in India, the first in the non-European British Empire and an influence on other nationalist movements.[54][55] Noted for nonviolent resistance after 1920,[56] it became the primary factor in ending British rule.[57] In 1947, the British Indian Empire was partitioned into two independent dominions,[58][59][60][61] a Hindu-majority dominion of India and a Muslim-majority dominion of Pakistan. A large-scale loss of life and an unprecedented migration accompanied the partition.[62]

India has been a federal republic since 1950, governed through a democratic parliamentary system. It is a pluralistic, multilingual and multi-ethnic society. India's population grew from 361 million in 1951 to over 1.4 billion in 2023.[63] During this time, its nominal per capita income increased from US$64 annually to US$2,601, and its literacy rate from 16.6% to 74%. A comparatively destitute country in 1951,[64] India has become a fast-growing major economy and a hub for information technology services, with an expanding middle class.[65] Indian movies and music increasingly influence global culture.[66] India has reduced its poverty rate, though at the cost of increasing economic inequality.[67] It is a nuclear-weapon state that ranks high in military expenditure. It has disputes over Kashmir with its neighbours, Pakistan and China, unresolved since the mid-20th century.[68] Among the socio-economic challenges India faces are gender inequality, child malnutrition,[69] and rising levels of air pollution.[70] India's land is megadiverse with four biodiversity hotspots.[71] India's wildlife, which has traditionally been viewed with tolerance in its culture,[72] is supported in protected habitats.

Etymology

[edit]According to the Oxford English Dictionary (2009), the name "India" is derived from the Classical Latin India, a reference to South Asia and an uncertain region to its east. In turn, "India" derived successively from Hellenistic Greek India (Ἰνδία), Ancient Greek Indos (Ἰνδός), Old Persian Hindush (an eastern province of the Achaemenid Empire), and ultimately its cognate, the Sanskrit Sindhu, or 'river'—specifically the Indus River, and by extension its well-settled southern basin.[73][74] The Ancient Greeks referred to the Indians as Indoi, 'the people of the Indus'.[75]

The term Bharat (Bhārat; pronounced [ˈbʱaːɾət] ⓘ), mentioned in both Indian epic poetry and the Constitution of India,[76][77] is used in its variations by many Indian languages. A modern rendering of the historical name Bharatavarsha, which applied originally to North India,[78][79] Bharat gained increased currency from the mid-19th century as a native name for India.[76][80]

Hindustan ([ɦɪndʊˈstaːn] ⓘ) is a Middle Persian name for India that became popular by the 13th century,[81] and was used widely since the era of the Mughal Empire. The meaning of Hindustan has varied, referring to a region encompassing the northern Indian subcontinent (present-day northern India and Pakistan) or to India in its near entirety.[76][80][82]

History

[edit]Ancient India

[edit]

55,000 years ago, the first modern humans, or Homo sapiens, arrived on the Indian subcontinent from Africa.[26][27][28] The earliest known modern human remains in South Asia date to about 30,000 years ago.[26] After 6500 BC, evidence for domestication of food crops and animals, construction of permanent structures, and storage of agricultural surplus appeared in Mehrgarh and other sites in Balochistan, Pakistan.[84] These gradually developed into the Indus Valley Civilisation,[85][84] the first urban culture in South Asia,[86] which flourished during 2500–1900 BC in Pakistan and western India.[87] Centred around cities such as Mohenjo-daro, Harappa, Dholavira, and Kalibangan, and relying on varied forms of subsistence, the civilisation engaged robustly in crafts production and wide-ranging trade.[86]

During the period 2000–500 BC, many regions of the subcontinent transitioned from the Chalcolithic cultures to the Iron Age ones.[88] The Vedas, the oldest scriptures associated with Hinduism,[89] were composed during this period,[90] and historians have analysed these to posit a Vedic culture in the Punjab region and the upper Gangetic Plain.[88] Most historians also consider this period to have encompassed several waves of Indo-Aryan migration into the subcontinent from the north-west.[89] The caste system, which created a hierarchy of priests, warriors, and free peasants, but which excluded indigenous peoples by labelling their occupations impure, arose during this period.[91] On the Deccan Plateau, archaeological evidence from this period suggests the existence of a chiefdom stage of political organisation.[88] In South India, a progression to sedentary life is indicated by the large number of megalithic monuments dating from this period,[92] as well as by nearby traces of agriculture, irrigation tanks, and craft traditions.[92]

In the late Vedic period, around the 6th century BCE, the small states and chiefdoms of the Ganges Plain and the north-western regions had consolidated into 16 major oligarchies and monarchies that were known as the mahajanapadas.[93][94] The emerging urbanisation gave rise to non-Vedic religious movements, two of which became independent religions. Jainism came into prominence during the life of its exemplar, Mahavira.[95] Buddhism, based on the teachings of Gautama Buddha, attracted followers from all social classes excepting the middle class; chronicling the life of the Buddha was central to the beginnings of recorded history in India.[96][97][98]

In an age of increasing urban wealth, both religions held up renunciation as an ideal,[99] and both established long-lasting monastic traditions. Politically, by the 3rd century BCE, the kingdom of Magadha had annexed or reduced other states to emerge as the Maurya Empire.[100] The empire was once thought to have controlled most of the subcontinent except the far south, but its core regions are now thought to have been separated by large autonomous areas.[101][102] The Mauryan kings are known as much for their empire-building and determined management of public life as for Ashoka's renunciation of militarism and far-flung advocacy of the Buddhist dhamma.[103][104]

The Sangam literature of the Tamil language reveals that, between 200 BC and 200 CE, the southern peninsula was ruled by the Cheras, the Cholas, and the Pandyas, dynasties that traded extensively with the Roman Empire and with West and Southeast Asia.[105][106] In North India, Hinduism asserted patriarchal control within the family, leading to increased subordination of women.[107][100] By the 4th and 5th centuries, the Gupta Empire had created a complex system of administration and taxation in the greater Ganges Plain; this system became a model for later Indian kingdoms.[108][109] Under the Guptas, a renewed Hinduism based on devotion, rather than the management of ritual, began to assert itself.[110] This renewal was reflected in a flowering of sculpture and architecture, which found patrons among an urban elite.[109] Classical Sanskrit literature flowered as well, and Indian science, astronomy, medicine, and mathematics made significant advances.[109]

Medieval India

[edit]

The Indian early medieval age, from 600 to 1200 CE, is defined by regional kingdoms and cultural diversity.[111] When Harsha of Kannauj, who ruled much of the Indo-Gangetic Plain from 606 to 647 CE, attempted to expand southwards, he was defeated by the Chalukya ruler of the Deccan.[112] When his successor attempted to expand eastwards, he was defeated by the Pala king of Bengal.[112] When the Chalukyas attempted to expand southwards, they were defeated by the Pallavas from farther south, who in turn were opposed by the Pandyas and the Cholas from still farther south.[112] No ruler of this period was able to create an empire and consistently control lands much beyond their core region.[111] During this time, pastoral peoples, whose land had been cleared to make way for the growing agricultural economy, were accommodated within caste society, as were new non-traditional ruling classes.[113] The caste system consequently began to show regional differences.[113]

In the 6th and 7th centuries, the first devotional hymns were created in the Tamil language.[114] They were imitated all over India and led to both the resurgence of Hinduism and the development of all modern languages of the subcontinent.[114] Indian royalty, big and small, and the temples they patronised drew citizens in great numbers to the capital cities, which became economic hubs as well.[115] Temple towns of various sizes began to appear everywhere as India underwent another urbanisation.[115] By the 8th and 9th centuries, the effects were felt in Southeast Asia, as South Indian culture and political systems were exported to lands that became part of modern-day Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Brunei, Cambodia, Vietnam, Philippines, Malaysia, and Indonesia.[116] Indian merchants, scholars, and sometimes armies were involved in this transmission; Southeast Asians took the initiative as well, with many sojourning in Indian seminaries and translating Buddhist and Hindu texts into their languages.[116]

After the 10th century, Muslim Central Asian nomadic clans, using swift-horse cavalry and raising vast armies united by ethnicity and religion, repeatedly overran South Asia's north-western plains, leading eventually to the establishment of the Islamic Delhi Sultanate in 1206.[117] The sultanate was to control much of North India and to make many forays into South India. Although at first disruptive for the Indian elites, the sultanate largely left its vast non-Muslim subject population to its own laws and customs.[118][119]

By repeatedly repulsing Mongol raiders in the 13th century, the sultanate saved India from the devastation visited on West and Central Asia, setting the scene for centuries of migration of fleeing soldiers, learned men, mystics, traders, artists, and artisans from that region into the subcontinent, thereby creating a syncretic Indo-Islamic culture in the north.[120][121] The sultanate's raiding and weakening of the regional kingdoms of South India paved the way for the indigenous Vijayanagara Empire.[122] Embracing a strong Shaivite tradition and building upon the military technology of the sultanate, the empire came to control much of peninsular India,[123] and was to influence South Indian society for long afterwards.[122]

Early modern India

[edit]

In the early 16th century, northern India, then under mainly Muslim rulers,[124] fell again to the superior mobility and firepower of a new generation of Central Asian warriors.[125] The resulting Mughal Empire did not stamp out the local societies it came to rule. Instead, it balanced and pacified them through new administrative practices[126][127] and diverse and inclusive ruling elites,[128] leading to more systematic, centralised, and uniform rule.[129] Eschewing tribal bonds and Islamic identity, especially under Akbar, the Mughals united their far-flung realms through loyalty, expressed through a Persianised culture, to an emperor who had near-divine status.[128]

The Mughal state's economic policies, deriving most revenues from agriculture[130] and mandating that taxes be paid in the well-regulated silver currency,[131] caused peasants and artisans to enter larger markets.[129] The relative peace maintained by the empire during much of the 17th century was a factor in India's economic expansion,[129] resulting in greater patronage of painting, literary forms, textiles, and architecture.[132] Newly coherent social groups in northern and western India, such as the Marathas, the Rajputs, and the Sikhs, gained military and governing ambitions during Mughal rule, which, through collaboration or adversity, gave them both recognition and military experience.[133] Expanding commerce during Mughal rule gave rise to new Indian commercial and political elites along the coasts of southern and eastern India.[133] As the empire disintegrated, many among these elites were able to seek and control their own affairs.[134]

By the early 18th century, with the lines between commercial and political dominance being increasingly blurred, a number of European trading companies, including the English East India Company, had established coastal outposts.[135][136] The East India Company's control of the seas, greater resources, and more advanced military training and technology led it to increasingly assert its military strength and caused it to become attractive to a portion of the Indian elite; these factors were crucial in allowing the company to gain control over the Bengal region by 1765 and sideline the other European companies.[137][135][138][139] Its further access to the riches of Bengal and the subsequent increased strength and size of its army enabled it to annexe or subdue most of India by the 1820s.[140] India was then no longer exporting manufactured goods as it long had, but was instead supplying the British Empire with raw materials. Many historians consider this to be the onset of India's colonial period.[135] By this time, with its economic power severely curtailed by the British parliament and having effectively been made an arm of British administration, the East India Company began more consciously to enter non-economic arenas, including education, social reform, and culture.[141]

Modern India

[edit]

Historians consider India's modern age to have begun sometime between 1848 and 1885. The appointment in 1848 of Lord Dalhousie as Governor General of the East India Company set the stage for changes essential to a modern state. These included the consolidation and demarcation of sovereignty, the surveillance of the population, and the education of citizens. Technological changes—among them, railways, canals, and the telegraph—were introduced not long after their introduction in Europe.[142][143][144][145] Disaffection with the company also grew during this time and set off the Indian Rebellion of 1857. Fed by diverse resentments and perceptions, including invasive British-style social reforms, harsh land taxes, and summary treatment of some rich landowners and princes, the rebellion rocked many regions of northern and central India and shook the foundations of Company rule.[146][147]

Although the rebellion was suppressed by 1858, it led to the dissolution of the East India Company and the direct administration of India by the British government. Proclaiming a unitary state and a gradual but limited British-style parliamentary system, the new rulers also protected princes and landed gentry as a feudal safeguard against future unrest.[148][149] In the decades following, public life gradually emerged all over India, leading eventually to the founding of the Indian National Congress (generally referred to as the Congress) in 1885.[150][151][152][153]

The rush of technology and the commercialisation of agriculture in the second half of the 19th century was marked by economic setbacks, and many small farmers became dependent on the whims of far-away markets.[154] There was an increase in the number of large-scale famines,[155] and, despite the risks of infrastructure development borne by Indian taxpayers, little industrial employment was generated for Indians.[156] There were also salutary effects: commercial cropping, especially in the newly canalled Punjab, led to increased food production for internal consumption.[157] The railway network provided critical famine relief,[158] notably reduced the cost of moving goods,[158] and helped nascent Indian-owned industry.[157]

After World War I, in which approximately one million Indians served,[159] a new period began. It was marked by British reforms but also repressive legislation, by more strident Indian calls for self-rule, and by the beginnings of a nonviolent movement of non-co-operation, of which Mahatma Gandhi would become the leader and enduring symbol.[160] During the 1930s, slow legislative reform was enacted by the British; the Indian National Congress won victories in the resulting elections.[161] The next decade was beset with crises: Indian participation in World War II, the Congress's final push for non-co-operation, and an upsurge of Muslim nationalism. All were capped by the advent of independence in 1947, but tempered by the partition of India into two states: India and Pakistan.[162]

Vital to India's self-image as an independent nation was its constitution, completed in 1950, which put in place a secular and democratic republic.[163] Economic liberalisation, which began in the 1980s and with the collaboration with Soviet Union for technical knowledge,[164] has created a large urban middle class, transformed India into one of the world's fastest-growing economies,[165] and increased its geopolitical influence. Yet, India is also shaped by persistent poverty, both rural and urban;[166] by religious and caste-related violence;[167] by Maoist-inspired Naxalite insurgencies;[168] and by separatism in Jammu and Kashmir and in Northeast India.[169] It has unresolved territorial disputes with China and with Pakistan.[170] India's sustained democratic freedoms are unique among the world's newer nations; however, in spite of its recent economic successes, freedom from want for its disadvantaged population remains a goal yet to be achieved.[171] As of 2025, poverty in India declined sharply, mainly due to government welfare programs.[172]

Geography

[edit]

India accounts for the bulk of the Indian subcontinent, lying atop the Indian tectonic plate, a part of the Indo-Australian Plate.[174] India's defining geological processes began 75 million years ago when the Indian Plate, then part of the southern supercontinent Gondwana, began a north-eastward drift caused by seafloor spreading to its south-west, and later, south and south-east.[174] Simultaneously, the vast Tethyan oceanic crust, to its northeast, began to subduct under the Eurasian Plate.[174] These dual processes, driven by convection in the Earth's mantle, both created the Indian Ocean and caused the Indian continental crust eventually to under-thrust Eurasia and to uplift the Himalayas.[174] Immediately south of the emerging Himalayas, plate movement created a vast crescent-shaped trough that rapidly filled with river-borne sediment[175] and now constitutes the Indo-Gangetic Plain.[176] The original Indian plate makes its first appearance above the sediment in the ancient Aravalli range, which extends from the Delhi Ridge in a southwesterly direction. To the west lies the Thar Desert, the eastern spread of which is checked by the Aravallis.[177][178][179]

The remaining Indian Plate survives as peninsular India, the oldest and geologically most stable part of India. It extends as far north as the Satpura and Vindhya ranges in central India. These parallel chains run from the Arabian Sea coast in Gujarat in the west to the coal-rich Chota Nagpur Plateau in Jharkhand in the east.[180] To the south, the remaining peninsular landmass, the Deccan Plateau, is flanked on the west and east by coastal ranges known as the Western and Eastern Ghats;[181] the plateau contains the country's oldest rock formations, some over one billion years old. Constituted in such fashion, India lies to the north of the equator between 6° 44′ and 35° 30′ north latitude[m] and 68° 7′ and 97° 25′ east longitude.[182]

India's coastline measures 7,517 kilometres (4,700 mi) in length; of this distance, 5,423 kilometres (3,400 mi) belong to peninsular India and 2,094 kilometres (1,300 mi) to the Andaman, Nicobar, and Lakshadweep island chains.[183] According to the Indian naval hydrographic charts, the mainland coastline consists of the following: 43% sandy beaches; 11% rocky shores, including cliffs; and 46% mudflats or marshy shores.[183] Major Himalayan-origin rivers that substantially flow through India include the Ganges and the Brahmaputra, both of which drain into the Bay of Bengal.[184]

Important tributaries of the Ganges include the Yamuna and the Kosi. The Kosi's extremely low gradient, caused by long-term silt deposition, leads to severe floods and course changes.[185][186] Major peninsular rivers, whose steeper gradients prevent their waters from flooding, include the Godavari, the Mahanadi, the Kaveri, and the Krishna, which also drain into the Bay of Bengal;[187] and the Narmada and the Tapti, which drain into the Arabian Sea.[188] Coastal features include the marshy Rann of Kutch of western India and the alluvial Sundarbans delta of eastern India; the latter is shared with Bangladesh.[189] India has two archipelagos: the Lakshadweep, coral atolls off India's south-western coast; and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, a volcanic chain in the Andaman Sea.[190]

Climate

[edit]

The Indian climate is strongly influenced by the Himalayas and the Thar Desert, both of which drive the economically and culturally pivotal summer and winter monsoons.[191] The Himalayas prevent cold Central Asian katabatic winds from blowing in, keeping the bulk of the Indian subcontinent warmer than most locations at similar latitudes.[192][193] The Thar Desert plays a crucial role in attracting the moisture-laden south-west summer monsoon winds that, between June and October, provide the majority of India's rainfall.[191]

Four major climatic groupings predominate in India: tropical wet, tropical dry, subtropical humid, and montane.[194] Temperatures in India have risen by 0.7 °C (1.3 °F) between 1901 and 2018.[195] Climate change in India is often thought to be the cause. The retreat of Himalayan glaciers has adversely affected the flow rate of the major Himalayan rivers, including the Ganges and the Brahmaputra.[196] According to some current projections, the number and severity of droughts in India will have markedly increased by the end of the present century.[197]

Biodiversity

[edit]

India is a megadiverse country, a term employed for 17 countries that display high biological diversity and contain many species exclusively indigenous, or endemic, to them.[199] India is the habitat for 8.6% of all mammals, 13.7% of bird species, 7.9% of reptile species, 6% of amphibian species, 12.2% of fish species, and 6.0% of all flowering plant species.[200][201] Fully a third of Indian plant species are endemic.[202] India also contains four of the world's 34 biodiversity hotspots,[71] or regions that display significant habitat loss in the presence of high endemism.[o][203]

India's most dense forests, such as the tropical moist forest of the Andaman Islands, the Western Ghats, and Northeast India, occupy approximately 3% of its land area.[204][205] Moderately dense forest, whose canopy density is between 40% and 70%, occupies 9.39% of India's land area.[204][205] It predominates in the temperate coniferous forest of the Himalayas, the moist deciduous sal forest of eastern India, and the dry deciduous teak forest of central and southern India.[206] India has two natural zones of thorn forest, one in the Deccan Plateau, immediately east of the Western Ghats, and the other in the western part of the Indo-Gangetic plain, now turned into rich agricultural land by irrigation, its features no longer visible.[207] Among the Indian subcontinent's notable indigenous trees are the astringent Azadirachta indica, or neem, which is widely used in rural Indian herbal medicine,[208] and the luxuriant Ficus religiosa, or peepul,[209] which is displayed on the ancient seals of Mohenjo-daro,[210] and under which the Buddha is recorded in the Pali canon to have sought enlightenment.[211]

Many Indian species have descended from those of Gondwana, the southern supercontinent from which India separated more than 100 million years ago.[212] India's subsequent collision with Eurasia set off a mass exchange of species. However, volcanism and climatic changes later caused the extinction of many endemic Indian forms.[213] Still later, mammals entered India from Asia through two zoogeographic passes flanking the Himalayas.[214] This lowered endemism among India's mammals, which stands at 12.6%, contrasting with 45.8% among reptiles and 55.8% among amphibians.[201] Among endemics are the vulnerable[215] hooded leaf monkey[216] and the threatened Beddome's toad[217][218] of the Western Ghats.

India contains 172 IUCN-designated threatened animal species, or 2.9% of endangered forms.[219] These include the endangered Bengal tiger and the Ganges river dolphin. Critically endangered species include the gharial, a crocodilian; the great Indian bustard; and the Indian white-rumped vulture, which has become nearly extinct by having ingested the carrion of diclofenac-treated cattle.[220] Before they were extensively used for agriculture and cleared for human settlement, the thorn forests of Punjab were mingled at intervals with open grasslands that were grazed by large herds of blackbuck preyed on by the Asiatic cheetah; the blackbuck, no longer extant in Punjab, is now severely endangered in India, and the cheetah is extinct.[221] The pervasive and ecologically devastating human encroachment of recent decades has critically endangered Indian wildlife. In response, the system of national parks and protected areas, first established in 1935, was expanded substantially. In 1972, India enacted the Wildlife Protection Act[222] and Project Tiger to safeguard crucial wilderness; the Forest Conservation Act was enacted in 1980 and amendments added in 1988.[223] India hosts more than five hundred wildlife sanctuaries and eighteen biosphere reserves,[224] four of which are part of the World Network of Biosphere Reserves; its eighty-nine wetlands are registered under the Ramsar Convention.[225]

Government and politics

[edit]Politics

[edit]

India is a parliamentary republic with a multi-party system.[227] It has six recognised national parties, including the Indian National Congress (generally referred to as the Congress) and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), and over 50 regional parties.[228] The Congress is considered the ideological centre in Indian political culture,[229] whereas the BJP is right-wing to far-right.[230][231][232] From 1950 to the late 1980s, Congress held a majority in India's parliament. Afterwards, it increasingly shared power with the BJP,[233] as well as with powerful regional parties, which forced multi-party coalition governments at the centre.[234]

In the general elections in 1951, 1957, and 1962, the Congress, led by Jawaharlal Nehru, won easy victories. On Nehru's death in 1964, Lal Bahadur Shastri briefly became prime minister; he was succeeded in 1966, by Nehru's daughter Indira Gandhi, who led the Congress to election victories in 1967 and 1971. Following public discontent with the state of emergency Indira Gandhi had declared in 1975, the Congress was voted out of power in 1977; Janata Party, which had opposed the emergency, was voted in. Its government lasted two years; Morarji Desai and Charan Singh served as prime ministers. After the Congress was returned to power in 1980, Indira Gandhi was assassinated and succeeded by Rajiv Gandhi, who won comfortably in the elections later that year. A National Front coalition led by the Janata Dal in alliance with the Left Front won the 1989 elections, with the subsequent government lasting just under two years, and V.P. Singh and Chandra Shekhar serving as prime ministers.[235] In the 1991 Indian general election, the Congress, as the largest single party, formed a minority government led by P. V. Narasimha Rao.[236]

After the 1996 Indian general election, the BJP formed a government briefly; it was followed by United Front coalitions, which depended on external political support. Two prime ministers served during this period: H.D. Deve Gowda and I.K. Gujral. In 1998, the BJP formed a coalition—the National Democratic Alliance (NDA). Led by Atal Bihari Vajpayee, the NDA became the first non-Congress, coalition government to complete a five-year term.[237] In the 2004 Indian general elections, no party won an absolute majority. Still, the Congress emerged as the largest single party, forming another successful coalition: the United Progressive Alliance (UPA). It had the support of left-leaning parties and MPs who opposed the BJP. The UPA returned to power in the 2009 general election with increased numbers, and it no longer required external support from India's communist parties.[238] Manmohan Singh became the first prime minister since Jawaharlal Nehru in 1957 and 1962 to be re-elected to a consecutive five-year term.[239] In the 2014 general election, the BJP became the first political party since 1984 to win an absolute majority.[240] In the 2019 general election, the BJP regained an absolute majority. In the 2024 general election, a BJP-led NDA coalition formed the government. Narendra Modi, a former chief minister of Gujarat, is in his third term as the prime minister of India and has served in the position since 26 May 2014.[241]

Government

[edit]India is a federation with a parliamentary system governed under the Constitution of India. Federalism in India defines the power distribution between the union and the states. India's form of government, traditionally described as "quasi-federal" with a strong centre and weak states,[243] has grown increasingly federal since the late 1990s as a result of political, economic, and social changes.[244][245]

The Government of India comprises three branches: the Executive, Legislature, and Judiciary.[246] The President of India is the ceremonial head of state,[247] who is elected indirectly for a five-year term by an electoral college comprising members of national and state legislatures.[248][249] The Prime Minister of India is the head of government and exercises most executive power.[250] Appointed by the president,[251] the prime minister is supported by the party or political alliance with a majority of seats in the lower house of parliament.[250] The executive of the Indian government consists of the president, the vice-president, and the Union Council of Ministers—with the cabinet being its executive committee—headed by the prime minister. Any minister holding a portfolio must be a member of one of the houses of parliament.[247] In the Indian parliamentary system, the executive is subordinate to the legislature; the prime minister and their council are directly responsible to the lower house of the parliament. Civil servants act as permanent executives and all decisions of the executive are implemented by them.[252]

The legislature of India is the bicameral parliament. Operating under a Westminster-style parliamentary system, it comprises an upper house called the Rajya Sabha (Council of States) and a lower house called the Lok Sabha (House of the People).[253] The Rajya Sabha is a permanent body of 245 members who serve staggered six-year terms with elections every 2 years.[254] Most are elected indirectly by the state and union territorial legislatures in numbers proportional to their state's share of the national population.[251] The Lok Sabha's 543 members are elected directly by popular vote among citizens aged at least 18;[255] they represent single-member constituencies for five-year terms.[256] Several seats from each state are reserved for candidates from Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes in proportion to their population within that state.[255]

India has a three-tier unitary independent judiciary[257] comprising the supreme court, headed by the Chief Justice of India, 25 high courts, and a large number of trial courts.[257] The supreme court has original jurisdiction over cases involving fundamental rights and over disputes between states and the centre and has appellate jurisdiction over the high courts.[258] It has the power to both strike down union or state laws which contravene the constitution[259] and invalidate any government action it deems unconstitutional.[260]

Administrative divisions

[edit]

India is a federal union comprising 28 states and 8 union territories.[12] All states, as well as the union territories of Jammu and Kashmir, Puducherry and the National Capital Territory of Delhi, have elected legislatures and governments following the Westminster system. The remaining five union territories are directly ruled by the central government through appointed administrators. In 1956, under the States Reorganisation Act, states were reorganised on a linguistic basis.[261] There are over a quarter of a million local government bodies at city, town, block, district and village levels.[262]

States

[edit]Union territories

[edit]Foreign relations

[edit]

India became a republic in 1950, remaining a member of the Commonwealth of Nations.[264][265] India strongly supported decolonisation in Africa and Asia in the 1950s; it played a leading role in the Non-Aligned Movement.[266] After initially cordial relations, India suffered a humiliating military defeat to China in a 1962 war.[267] Another military conflict followed in 1967 in which India successfully repelled a Chinese attack.[268]

India has had uneasy relations with its western neighbour, Pakistan. The two countries went to war in 1947, 1965, 1971, and 1999. Three of these wars were fought over the disputed territory of Kashmir. In contrast, the 1971 war followed India's support for the independence of Bangladesh.[269] After the 1965 war with Pakistan, India began to pursue close military and economic ties with the Soviet Union. By the late 1960s, the Soviet Union was its largest arms supplier.[270] India has played a key role in the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation and the World Trade Organization. The nation has supplied 100,000 military and police personnel in 35 UN peacekeeping operations.[citation needed]

China's nuclear test of 1964 and threats to intervene in support of Pakistan in the 1965 war caused India to produce nuclear weapons.[271] India conducted its first nuclear weapons test in 1974 and carried out additional underground testing in 1998. India has signed neither the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty nor the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, considering both to be flawed and discriminatory.[272] India maintains a "no first use" nuclear policy and is developing a nuclear triad capability as a part of its "Minimum Credible Deterrence" doctrine.[273][274]

Since the end of the Cold War, India has increased its economic, strategic, and military cooperation with the United States and the European Union.[275] In 2008, a civilian nuclear agreement was signed between India and the United States. Although India possessed nuclear weapons at the time and was not a party to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, it received waivers from the International Atomic Energy Agency and the Nuclear Suppliers Group, ending earlier restrictions on India's nuclear technology and commerce; India subsequently signed co-operation agreements involving civilian nuclear energy with Russia,[276] France,[277] the United Kingdom,[278] and Canada.[279]

Military

[edit]

The President of India is the supreme commander of the nation's armed forces. With 1.45 million active troops, they are the world's second-largest military. It comprises the Indian Army, the Indian Navy, the Indian Air Force, and the Indian Coast Guard.[281] The official Indian defence budget for 2011 was US$36.03 billion, or 1.83% of GDP.[282] Defence expenditure was pegged at US$70.12 billion for fiscal year 2022–23 and, increased 9.8% on the previous fiscal year.[283][284] India is the world's second-largest arms importer; between 2016 and 2020, it accounted for 9.5% of the total global arms imports.[285] Much of the military expenditure was focused on defence against Pakistan and countering growing Chinese influence in the Indian Ocean.[286]

Economy

[edit]According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the Indian economy in 2024 was nominally worth $3.94 trillion; it is the fifth-largest economy by market exchange rates and is, at around $15.0 trillion, the third-largest by purchasing power parity (PPP).[16] With its average annual GDP growth rate of 5.8% over the past two decades, and reaching 6.1% during 2011–2012,[290] India is one of the world's fastest-growing economies.[291] However, due to its low GDP per capita—which ranks 136th in the world in nominal per capita income and 125th in per capita income adjusted for purchasing power parity (PPP)—the vast majority of Indians fall into the low-income group.[292][293]

Until 1991, all Indian governments followed protectionist policies that were influenced by socialist economics. Widespread state intervention and regulation largely walled the economy off from the outside world. An acute balance of payments crisis in 1991 forced the nation to liberalise its economy;[294] since then, it has moved increasingly towards a free-market system[295][296] by emphasising both foreign trade and direct investment inflows.[297] India has been a member of World Trade Organization since 1 January 1995.[298]

The 522-million-worker Indian labour force is the world's second largest, as of 2017[update].[281] The service sector makes up 55.6% of GDP, the industrial sector 26.3% and the agricultural sector 18.1%. India's foreign exchange remittances of US$100 billion in 2022,[299] highest in the world, were contributed to its economy by 32 million Indians working in foreign countries.[300] In 2006, the share of external trade in India's GDP stood at 24%, up from 6% in 1985.[295] In 2008, India's share of world trade was 1.7%;[301] In 2021, India was the world's ninth-largest importer and the sixteenth-largest exporter.[302] Between 2001 and 2011, the contribution of petrochemical and engineering goods to total exports grew from 14% to 42%.[303] India was the world's second-largest textile exporter after China in the 2013 calendar year.[304]

Averaging an economic growth rate of 7.5% for several years before 2007,[295] India has more than doubled its hourly wage rates during the first decade of the 21st century.[305] Some 431 million Indians have left poverty since 1985; India's middle classes are projected to number around 580 million by 2030.[306] In 2024, India's consumer market was the world's third largest.[307] India's nominal GDP per capita increased steadily from US$308 in 1991, when economic liberalisation began, to US$1,380 in 2010, to an estimated US$2,731 in 2024. It is expected to grow to US$3,264 by 2026.[16]

Industries

[edit]The Indian automotive industry, the world's second-fastest growing, increased domestic sales by 26% during 2009–2010,[308] and exports by 36% during 2008–2009.[309] In 2022, India became the world's third-largest vehicle market after China and the United States, surpassing Japan.[310] At the end of 2011, the Indian IT industry employed 2.8 million professionals, generated revenues close to US$100 billion equalling 7.5% of Indian GDP, and contributed 26% of India's merchandise exports.[311]

The pharmaceutical industry in India includes 3,000 pharmaceutical companies and 10,500 manufacturing units; India is the world's third-largest pharmaceutical producer, largest producer of generic medicines and supply up to 50–60% of global vaccines demand, these all contribute up to US$24.44 billions in exports and India's local pharmaceutical market is estimated up to US$42 billion.[312][313] India is among the top 12 biotech destinations in the world.[314][315] The Indian biotech industry grew by 15.1% in 2012–2013, increasing its revenues from ₹204.4 billion (Indian rupees) to ₹235.24 billion (US$3.94 billion at June 2013 exchange rates).[316]

Energy

[edit]India's capacity to generate electrical power is 300 gigawatts, of which 42 gigawatts is renewable.[317] The country's usage of coal is a major cause of India's greenhouse gas emissions, but its renewable energy is competing strongly.[318][better source needed] India emits about 7% of global greenhouse gas emissions. This equates to about 2.5 tons of carbon dioxide per person per year, which is half the world average.[319][320] Increasing access to electricity and clean cooking with liquefied petroleum gas have been priorities for energy in India.[321]

Socio-economic challenges

[edit]Despite economic growth during recent decades, India continues to face socio-economic challenges. In 2006, India contained the largest number of people living below the World Bank's international poverty line of US$1.25 per day.[323] The proportion decreased from 60% in 1981 to 42% in 2005.[324] Under the World Bank's later revised poverty line, it was 21%-22.5 in 2011.[p][326][327] In 2019, the estimates had gone down to 10.2%.[327] In 2014, 30.7% of India's children under the age of five were underweight.[328] According to a Food and Agriculture Organization report in 2015, 15% of the population was undernourished.[329][330] The Midday Meal Scheme attempts to lower these rates.[331]

A 2018 Walk Free Foundation report estimated that nearly 8 million people in India were living in different forms of modern slavery, such as bonded labour, child labour, human trafficking, and forced begging.[332] According to the 2011 census, there were 10.1 million child labourers in the country, a decline of 2.6 million from 12.6 million in 2001.[333]

Since 1991, economic inequality between India's states has consistently grown: the per-capita net state domestic product of the richest states in 2007 was 3.2 times that of the poorest.[334] Corruption in India is perceived to have decreased. According to the Corruption Perceptions Index, India ranked 78th out of 180 countries in 2018, an improvement from 85th in 2014.[335][336]

As of 2025, poverty in India declined sharply. According to the World Bank report, extreme poverty fall from 16.2% in 2011-12 to 2.3% in 2022-23. In rural areas it fell from 18.4% to 2.8%, and in urban areas, from 10.7% to 1.1%. 378 million peopole were lifted from poverty and 171 million from extreme poverty. The main reason, according to the World Bank, is not economic growth but different government welfare programs, like transferring food and money to the people with low income, improving their access to services.[172]

Demographics

[edit]With an estimated 1,428,627,663 residents in 2023, India is the world's most populous country.[13] 1,210,193,422 residents were reported in the 2011 provisional census report.[337] Its population grew by 17.64% from 2001 to 2011,[338] compared to 21.54% growth in the previous decade (1991–2001).[338] The human sex ratio, according to the 2011 census, is 940 females per 1,000 males.[337] The median age was 28.7 in 2020.[281]

The first post-colonial census, conducted in 1951, counted 361 million people.[339] Medical advances made in the last 50 years as well as increased agricultural productivity brought about by the "Green Revolution" have caused India's population to grow rapidly.[340] The life expectancy in India is 70 years to 71.5 years for women, and 68.7 years for men.[281] There are around 93 physicians per 100,000 people.[341]

Urbanisation

[edit]Migration from rural to urban areas has been an important dynamic in India's recent history. The number of people living in urban areas grew by 31.2% between 1991 and 2001.[342] In 2001, over 70% lived in rural areas.[343][344] The level of urbanisation increased further from 27.81% in the 2001 census to 31.16% in the 2011 census. The slowing down of the overall population growth rate was due to the sharp decline in the growth rate in rural areas since 1991.[345] In the 2011 census, there were 53 million-plus urban agglomerations in India. Among them Mumbai, Delhi, Kolkata, Chennai, Bengaluru, Hyderabad and Ahmedabad, in decreasing order by population.[346]

Languages

[edit]Among speakers of the Indian languages, 74% speak Indo-Aryan languages (the easternmost branch of the Indo-European languages), 24% speak Dravidian languages (indigenous to South Asia and spoken widely before the spread of Indo-Aryan languages), and 2% speak Austroasiatic languages or the Sino-Tibetan languages. India has no national language.[347] Hindi, with the largest number of speakers, is the official language of the government.[348][349] English is used extensively in business and administration and has the status of a "subsidiary official language";[6] it is important in education, especially as a medium of higher education. Each state and union territory has one or more official languages, and the constitution recognises in particular 22 "scheduled languages".

Religion

[edit]The 2011 census reported the religion in India with the largest number of followers was Hinduism (79.80% of the population), followed by Islam (14.23%); the remaining were Christianity (2.30%), Sikhism (1.72%), Buddhism (0.70%), Jainism (0.36%) and others[q] (0.9%).[11] India has the third-largest Muslim population—the largest for a non-Muslim majority country.[350][351]

Education

[edit]

The literacy rate in 2011 was 74.04%: 65.46% among females and 82.14% among males.[352] The rural-urban literacy gap, which was 21.2 percentage points in 2001, dropped to 16.1 percentage points in 2011. The improvement in the rural literacy rate is twice that of urban areas.[345] Kerala is the most literate state with 93.91% literacy; while Bihar the least with 63.82%.[352] In the 2011 census, about 73% of the population was literate, with 81% for men and 65% for women. This compares to 1981 when the respective rates were 41%, 53% and 29%. In 1951, the rates were 18%, 27% and 9%. In 1921, the rates 7%, 12% and 2%. In 1891, they were 5%, 9% and 1%,[353][354] According to Latika Chaudhary, in 1911 there were under three primary schools for every ten villages. Statistically, more caste and religious diversity reduced private spending. Primary schools taught literacy, so local diversity limited its growth.[355]

The education system of India is the world's second-largest.[356] India has over 900 universities, 40,000 colleges[357] and 1.5 million schools.[358] In India's higher education system, a significant number of seats are reserved under affirmative action policies for the historically disadvantaged. In recent decades India's improved education system is often cited as one of the main contributors to its economic development.[359][360]

Health

[edit]The life expectancy at birth has increased from 49.7 years in 1970–1975 to 72.0 years in 2023.[361][362] The under-five mortality rate for the country was 113 per 1,000 live births in 1994 whereas in 2018 it reduced to 41.1 per 1,000 live births.[361]

India bears a disproportionately large burden of the world's tuberculosis rates, with World Health Organization (WHO) statistics for 2022 estimating 2.8 million new infections annually, accounting for 26% of the global total.[363] It is estimated that approximately 40% of the population of India carry tuberculosis infection.[364]

In 2018 chronic obstructive pulmonary disease was the leading cause of death after heart disease. The 10 most polluted cities in the world are all in northern India with more than 140 million people breathing air 10 times or more over the WHO safe limit. In 2017, air pollution killed 1.24 million Indians.[365]

Culture

[edit]Society

[edit]The Indian caste system embodies much of the social stratification and many of the social restrictions found on the Indian subcontinent. Social classes are defined by thousands of endogamous hereditary groups, often termed as jātis, or "castes".[366] India abolished untouchability in 1950 with the adoption of the constitution and has since enacted other anti-discriminatory laws and social welfare initiatives.[r] However, the system continues to be dominant in India, and caste-based inequality, discrimination, segregation, and violence persist.[368][369]

Multi-generational patrilineal joint families have been the norm in India, though nuclear families are becoming common in urban areas.[370] An overwhelming majority of Indians have their marriages arranged by their parents or other family elders.[371] Marriage is thought to be for life,[371] and the divorce rate is extremely low,[372] with less than one in a thousand marriages ending in divorce.[373] Child marriages are common, especially in rural areas; many women wed before reaching 18, which is their legal marriageable age.[374] Female infanticide in India, and lately female foeticide, have created skewed gender ratios; the number of missing women in the country quadrupled from 15 million to 63 million in the 50 years ending in 2014, faster than the population growth during the same period.[375] According to an Indian government study, an additional 21 million girls are unwanted and do not receive adequate care.[376] Despite a government ban on sex-selective foeticide, the practice remains commonplace in India, the result of a preference for boys in a patriarchal society.[377] The payment of dowry, although illegal, remains widespread across class lines.[378] Deaths resulting from dowry, mostly from bride burning, are on the rise, despite stringent anti-dowry laws.[379]

Visual art

[edit]India has a very ancient tradition of art, which has exchanged many influences with the rest of Eurasia, especially in the first millennium, when Buddhist art spread with Indian religions to Central, East and Southeast Asia, the last also greatly influenced by Hindu art.[380] Thousands of seals from the Indus Valley civilisation of the third millennium BCE have been found, usually carved with animals, but also some with human figures. The Pashupati seal, excavated in Mohenjo-daro, Pakistan, in 1928–29, is the best known.[381][382] After this there is a long period with virtually nothing surviving.[382][383] Almost all surviving ancient Indian art thereafter is in various forms of religious sculpture in durable materials, or coins. There was probably originally far more in wood, which is lost. In north India Mauryan art is the first imperial movement.[384][385][386]

In the first millennium CE, Buddhist art spread with Indian religions to Central, East and Southeast Asia, the last also greatly influenced by Hindu art.[387] Over the following centuries a distinctly Indian style of sculpting the human figure developed, with less interest in articulating precise anatomy than ancient Greek sculpture but showing smoothly flowing forms expressing prana ("breath" or life-force).[388][389] This is often complicated by the need to give figures multiple arms or heads, or represent different genders on the left and right of figures, as with the Ardhanarishvara form of Shiva and Parvati.[390][391]

Most of the earliest large sculpture is Buddhist, either excavated from Buddhist stupas such as Sanchi, Sarnath and Amaravati,[392] or is rock cut reliefs at sites such as Ajanta, Karla and Ellora. Hindu and Jain sites appear rather later.[393][394] In spite of this complex mixture of religious traditions, generally, the prevailing artistic style at any time and place has been shared by the major religious groups, and sculptors probably usually served all communities.[395] Gupta art, at its peak c. 300 CE – c. 500 CE, is often regarded as a classical period whose influence lingered for many centuries after; it saw a new dominance of Hindu sculpture, as at the Elephanta Caves.[396][397] Across the north, this became rather stiff and formulaic after c. 800 CE, though rich with finely carved detail in the surrounds of statues.[398] But in the South, under the Pallava and Chola dynasties, sculpture in both stone and bronze had a sustained period of great achievement; the large bronzes with Shiva as Nataraja have become an iconic symbol of India.[399][400]

Ancient paintings have only survived at a few sites, of which the crowded scenes of court life in the Ajanta Caves are some of the most important.[401][402] Painted manuscripts of religious texts survive from Eastern India from 10th century onwards, most of the earliest being Buddhist and later Jain. These significantly influenced later artistic styles.[403] The Persian-derived Deccan painting, starting just before the Mughal miniature, between them give the first large body of secular painting, with an emphasis on portraits, and the recording of princely pleasures and wars.[404][405] The style spread to Hindu courts, especially among the Rajputs, and developed a variety of styles, with the smaller courts often the most innovative, with figures such as Nihâl Chand and Nainsukh.[406][407] As a market developed among European residents, it was supplied by Company painting by Indian artists with considerable Western influence.[408][409] In the 19th century, cheap Kalighat paintings of gods and everyday life, done on paper, were urban folk art from Calcutta, which later saw the Bengal School of Art, reflecting the art colleges founded by the British, the first movement in modern Indian painting.[410][411]

-

Krishna Fluting to the Milkmaids, Kangra painting, 1775–1785

Clothing

[edit]

From ancient times until the advent of the modern, the most widely worn traditional dress in India was draped.[412] For women it took the form of a sari, a single piece of cloth many yards long.[412] The sari was traditionally wrapped around the lower body and the shoulder.[412] In its modern form, it is combined with an underskirt, or Indian petticoat, and tucked in the waist band for more secure fastening. It is also commonly worn with an Indian blouse, or choli, which serves as the primary upper-body garment, the sari's end—passing over the shoulder—covering the midriff and obscuring the upper body's contours.[412] For men, a similar but shorter length of cloth, the dhoti, has served as a lower-body garment.[413]

The use of stitched clothes became widespread after Muslim rule was established at first by the Delhi sultanate (c. 1300 CE) and then continued by the Mughal Empire (c. 1525 CE).[414] Among the garments introduced during this time and still commonly worn are: the shalwars and pyjamas, both styles of trousers, and the tunics kurta and kameez.[414] In southern India, the traditional draped garments were to see much longer continuous use.[414]

Salwars are atypically wide at the waist but narrow to a cuffed bottom. They are held up by a drawstring, which causes them to become pleated around the waist.[415] The pants can be wide and baggy, or they can be cut quite narrow, on the bias, in which case they are called churidars. When they are ordinarily wide at the waist and their bottoms are hemmed but not cuffed, they are called pyjamas. The kameez is a long shirt or tunic,[416] its side seams left open below the waistline.[417] The kurta is traditionally collarless and made of cotton or silk; it is worn plain or with embroidered decoration, such as chikankari; and typically falls to either just above or just below the wearer's knees.[418]

In the last 50 years, fashions have changed a great deal in India. Increasingly, in urban northern India, the sari is no longer the apparel of everyday wear, though they remain popular on formal occasions.[419] The traditional shalwar kameez is rarely worn by younger urban women, who favour churidars or jeans.[419] In office settings, ubiquitous air conditioning allows men to wear sports jackets year-round.[419] For weddings and formal occasions, men in the middle and upper classes often wear Jodhpuri bandhgala, or short Nehru jackets, with pants, with the groom and his groomsmen sporting sherwanis and churidars.[419] The dhoti, once the universal garment of Hindu males, the wearing of which in the homespun and handwoven khadi allowed Gandhi to bring Indian nationalism to the millions,[420] is seldom seen in the cities.[419]

Cuisine

[edit]

The foundation of a typical Indian meal is a cereal cooked plainly and complemented with flavourful savoury dishes.[421] The cooked cereal could be steamed rice; chapati, a thin unleavened bread;[422] the idli, a steamed breakfast cake; or dosa, a griddled pancake.[423] The savoury dishes might include lentils, pulses and vegetables commonly spiced with ginger and garlic, but also with a combination of spices that may include coriander, cumin, turmeric, cinnamon, cardamon and others.[421] They might also include poultry, fish, or meat dishes. In some instances, the ingredients may be mixed during the cooking process.[424]

A platter, or thali, used for eating usually has a central place reserved for the cooked cereal, and peripheral ones for the flavourful accompaniments. The cereal and its accompaniments are eaten simultaneously rather than a piecemeal manner. This is accomplished by mixing—for example of rice and lentils—or folding, wrapping, scooping or dipping—such as chapati and cooked vegetables.[421]

India has distinctive vegetarian cuisines, each a feature of the geographical and cultural histories of its adherents.[426] About 20% to 39% of India's population consists of vegetarians.[427][428] Much of this stems from caste hierarchy, as upper castes, such as the Brahmins, consider vegetarian food to be "pure".[429][430] Although meat is eaten widely in India, the proportional consumption of meat in the overall diet is low.[431] Unlike China, which has increased its per capita meat consumption substantially in its years of increased economic growth, in India the strong dietary traditions have contributed to dairy, rather than meat, becoming the preferred form of animal protein consumption.[432]

The most significant import of cooking techniques into India during the last millennium occurred during the Mughal Empire. Dishes such as the pilaf,[433] developed in the Abbasid caliphate,[434] and cooking techniques such as the marinating of meat in yogurt, spread into northern India from regions to its northwest.[435] To the simple yogurt marinade of Persia, onions, garlic, almonds, and spices began to be added in India.[435] Rice was partially cooked and layered alternately with the sauteed meat, the pot sealed tightly, and slow cooked according to another Persian cooking technique, to produce what has today become biryani,[435] a feature of festive dining in many parts of India.[436]

In the food served in Indian restaurants worldwide, the diversity of Indian food has been partially concealed by the dominance of Punjabi cuisine. The popularity of tandoori chicken—cooked in the tandoor oven, which had traditionally been used for baking bread in the rural Punjab and the Delhi region, especially among Muslims, but which is originally from Central Asia—dates to the 1950s, and was caused in large part by an entrepreneurial response among people from the Punjab who had been displaced by the 1947 partition.[426]

Sports

[edit]Several traditional sports, such as kabaddi, kho kho, pehlwani, gilli-danda, hopscotch and martial arts such as Kalarippayattu and marma adi, remain popular in India. Chess is commonly held to have originated in India as chaturaṅga;[438] in recent years,[when?] there has been a rise in the number of Indian grandmasters[439] and world champions.[440] Parcheesi is derived from Pachisi, another traditional Indian pastime, which in early modern times was played on a giant marble court by Mughal emperor Akbar.[441]

Cricket is the most popular sport in India.[442] India is one of the most successful cricket teams in the world, having won two Cricket World Cups, two T20 World Cups, three Champions Trophies, and finished as runners-up twice in the World Test Championship. India has won a record eight field hockey gold medals in the summer Olympics.[443]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Originally written in Sanskritised Bengali and adopted as the national anthem in its Hindi translation

- ^ "[...] Jana Gana Mana is the National Anthem of India, subject to such alterations in the words as the Government may authorise as occasion arises; and the song Vande Mataram, which has played a historic part in the struggle for Indian freedom, shall be honoured equally with Jana Gana Mana and shall have equal status with it."[5]

- ^ Written in a mixture of Sanskrit and Sanskritised Bengali

- ^ According to Part XVII of the Constitution of India, Hindi in the Devanagari script is the official language of the Union, along with English as an additional official language.[1][6][7] States and union territories can have a different official language of their own other than Hindi or English.

- ^ Not all the state-level official languages are in the eighth schedule and not all the scheduled languages are state-level official languages. For example, the Sindhi language is an 8th scheduled but not a state-level official language.

- ^ Kashmiri and Dogri language are the official languages of Jammu and Kashmir which is currently a union territory and no longer the former state.

- ^

- According to Ethnologue, there are 424 living indigenous languages in India, in contrast to 11 extinct indigenous languages. In addition, there are 30 living non-indigenous languages.[10]

- Different sources give widely differing figures, primarily based on how the terms "language" and "dialect" are defined and grouped.

- ^ "The country's exact size is subject to debate because some borders are disputed. The Indian government lists the total area as 3,287,260 km2 (1,269,220 sq mi) and the total land area as 3,060,500 km2 (1,181,700 sq mi); the United Nations lists the total area as 3,287,263 km2 (1,269,219 sq mi) and total land area as 2,973,190 km2 (1,147,960 sq mi)."[12]

- ^ See Date and time notation in India.

- ^ ISO: Bhārat Gaṇarājya

- ^ The Government of India also regards Afghanistan as a bordering country, as it considers all of Kashmir to be part of India.[25] However, this is disputed, and the region bordering Afghanistan is administered by Pakistan.

- ^ "A Chinese pilgrim also recorded evidence of the caste system as he could observe it. According to this evidence the treatment meted out to untouchables such as the Chandalas was very similar to that which they experienced in later periods. This would contradict assertions that this rigid form of the caste system emerged in India only as a reaction to the Islamic conquest."[40]

- ^ The northernmost point under Indian control is the disputed Siachen Glacier in Jammu and Kashmir; however, the Government of India regards the entire region of the former princely state of Jammu and Kashmir, including the Gilgit-Baltistan administered by Pakistan, to be its territory. It therefore assigns the latitude 37° 6′ to its northernmost point.

- ^ A forest cover is moderately dense if between 40% and 70% of its area is covered by its tree canopy.

- ^ A biodiversity hotspot is a biogeographical region which has more than 1,500 vascular plant species, but less than 30% of its primary habitat.[203]

- ^ In 2015, the World Bank raised its international poverty line to $1.90 per day.[325]

- ^ Besides specific religions, the last two categories in the 2011 census were "Other religions and persuasions" (0.65%) and "Religion not stated" (0.23%).

- ^ "Untouchability" is abolished and its practice in any form is forbidden. The enforcement of any disability arising out of "Untouchability" shall be an offence punishable in accordance with law.[367]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c National Informatics Centre 2005.

- ^ a b c d "National Symbols | National Portal of India". India.gov.in. Archived from the original on 4 February 2017. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

The National Anthem of India Jana Gana Mana, composed originally in Bengali by Rabindranath Tagore, was adopted in its Hindi version by the Constituent Assembly as the National Anthem of India on 24 January 1950.

- ^ "National anthem of India: a brief on 'Jana Gana Mana'". News18. 14 August 2012. Archived from the original on 17 April 2019. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ^ Wolpert 2003, p. 1.

- ^ Constituent Assembly of India 1950.

- ^ a b Ministry of Home Affairs 1960.

- ^ "Profile | National Portal of India". India.gov.in. Archived from the original on 30 August 2013. Retrieved 23 August 2013.

- ^ "Constitutional Provisions – Official Language Related Part-17 of the Constitution of India". Department of Official Language via Government of India. Archived from the original on 18 April 2021. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ "50th Report of the Commissioner for Linguistic Minorities in India (July 2012 to June 2013)" (PDF). Commissioner for Linguistic Minorities, Ministry of Minority Affairs, Government of India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2016. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

- ^ Eberhard, David M.; Simons, Gary F.; Fennig, Charles D. (2025). "India". Ethnologue: Languages of the World (28 ed.).

- ^ a b "C −1 Population by religious community – 2011". Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner. Archived from the original on 25 August 2015. Retrieved 25 August 2015.

- ^ a b Library of Congress 2004.

- ^ a b "World Population Prospects". Population Division – United Nations. Retrieved 2 July 2023.

- ^ "Population Enumeration Data (Final Population)". 2011 Census Data. Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Archived from the original on 22 May 2016. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "A – 2 Decadal Variation in Population Since 1901" (PDF). 2011 Census Data. Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 April 2016. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2025 Edition. (India)". www.imf.org. International Monetary Fund. 22 April 2025. Retrieved 26 May 2025.

- ^ "Gini index (World Bank estimate) – India". World Bank.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2025" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 6 May 2025. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 May 2025. Retrieved 6 May 2025.

- ^ "List of all left- & right-driving countries around the world". worldstandards.eu. 13 May 2020. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- ^

- The Essential Desk Reference. Oxford University Press. 2002. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-19-512873-4. "Official name: Republic of India.";

- John Da Graça (2017). Heads of State and Government. London: Macmillan. p. 421. ISBN 978-1-349-65771-1. "Official name: Republic of India; Bharat Ganarajya (Hindi)";

- Graham Rhind (2017). Global Sourcebook of Address Data Management: A Guide to Address Formats and Data in 194 Countries. Taylor & Francis. p. 302. ISBN 978-1-351-93326-1. "Official name: Republic of India; Bharat.";

- Bradnock, Robert W. (2015). The Routledge Atlas of South Asian Affairs. Routledge. p. 108. ISBN 978-1-317-40511-5. "Official name: English: Republic of India; Hindi:Bharat Ganarajya";

- Penguin Compact Atlas of the World. Penguin. 2012. p. 140. ISBN 978-0-7566-9859-1. "Official name: Republic of India";

- Merriam-Webster's Geographical Dictionary (3rd ed.). Merriam-Webster. 1997. pp. 515–516. ISBN 978-0-87779-546-9. "Officially, Republic of India";

- Complete Atlas of the World: The Definitive View of the Earth (3rd ed.). DK Publishing. 2016. p. 54. ISBN 978-1-4654-5528-4. "Official name: Republic of India";

- Worldwide Government Directory with Intergovernmental Organizations 2013. CQ Press. 2013. p. 726. ISBN 978-1-4522-9937-2.

- ^ James, K. S.; Sekher, T. V. (2024). "India's Population Change: Critical Issues and Prospects.". In James, K. S.; Sekher, T. V. (eds.). India Population Report (1st ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–18. doi:10.1017/9781009318846.003. ISBN 978-1-009-31886-0.

- ^ Metcalf & Metcalf 2012, p. 327: "Even though much remains to be done, especially in regard to eradicating poverty and securing effective structures of governance, India's achievements since independence in sustaining freedom and democracy have been singular among the world's new nations."

- ^ Stein, Burton (2012). Arnold, David (ed.). A History of India. The Blackwell History of the World Series (2nd ed.). Wiley-Blackwell.

One of these is the idea of India as 'the world's largest democracy', but a democracy forged less by the creation of representative institutions and expanding electorate under British rule than by the endeavours of India's founding fathers – Gandhi, Nehru, Patel and Ambedkar – and the labours of the Constituent Assembly between 1946 and 1949, embodied in the Indian constitution of 1950. This democratic order, reinforced by the regular holding of nationwide elections and polling for the state assemblies, has, it can be argued, consistently underpinned a fundamentally democratic state structure – despite the anomaly of the Emergency and the apparent durability of the Gandhi-Nehru dynasty.

- ^ Fisher 2018, pp. 184–185: "Since 1947, India's internal disputes over its national identity, while periodically bitter and occasionally punctuated by violence, have been largely managed with remarkable and sustained commitment to national unity and democracy."

- ^ "Ministry of Home Affairs (Department of Border Management)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 March 2015. Retrieved 1 September 2008.

- ^ a b c Petraglia & Allchin 2007, p. 10: "Y-Chromosome and Mt-DNA data support the colonization of South Asia by modern humans originating in Africa. [...] Coalescence dates for most non-European populations average to between 73 and 55 ka."

- ^ a b Dyson 2018, p. 1: "Modern human beings—Homo sapiens—originated in Africa. Then, intermittently, sometime between 60,000 and 80,000 years ago, tiny groups of them began to enter the north-west of the Indian subcontinent. It seems likely that initially they came by way of the coast. [...] it is virtually certain that there were Homo sapiens in the subcontinent 55,000 years ago, even though the earliest fossils that have been found of them date to only about 30,000 years before the present."

- ^ a b Fisher 2018, p. 23: "Scholars estimate that the first successful expansion of the Homo sapiens range beyond Africa and across the Arabian Peninsula occurred from as early as 80,000 years ago to as late as 40,000 years ago, although there may have been prior unsuccessful emigrations. Some of their descendants extended the human range ever further in each generation, spreading into each habitable land they encountered. One human channel was along the warm and productive coastal lands of the Persian Gulf and northern Indian Ocean. Eventually, various bands entered India between 75,000 years ago and 35,000 years ago."

- ^ Dyson 2018, p. 28.

- ^

- Dyson 2018, pp. 4–5.

- Fisher 2018, p. 33.

- ^ Lowe 2015, pp. 1–2: "It consists of 1,028 hymns (sūktas), highly crafted poetic compositions originally intended for recital during rituals and for the invocation of and communication with the Indo-Aryan gods. Modern scholarly opinion largely agrees that these hymns were composed between around 1500 BCE and 1200 BCE, during the eastward migration of the Indo-Aryan tribes from the mountains of what is today northern Afghanistan across the Punjab into north India."

- ^

- Witzel 2003, pp. 68–70: "It is known from internal evidence that the Vedic texts were orally composed in northern India, at first in the Greater Punjab and later on also in more eastern areas, including northern Bihar, between ca. 1500 BCE and ca. 500–400 BCE. The oldest text, the Rgveda, must have been more or less contemporary with the Mitanni texts of northern Syria/Iraq (1450–1350 BCE); [...] The Vedic texts were orally composed and transmitted, without the use of script, in an unbroken line of transmission from teacher to student that was formalised early on. This ensured an impeccable textual transmission superior to the classical texts of other cultures; it is in fact something of a tape-recording of ca. 1500–500 BCE. Not just the actual words, but even the long-lost musical (tonal) accent (as in old Greek or in Japanese) has been preserved up to the present. [...] The RV text was composed before the introduction and massive use of iron, that is before ca. 1200–1000 BCE."

- Doniger 2014, pp. xviii, 10: "A Chronology of Hinduism: ca. 1500–1000 BCE Rig Veda; ca. 1200–900 BCE Yajur Veda, Sama Veda and Atharva Veda [...] Hindu texts began with the Rig Veda ('Knowledge of Verses'), composed in northwest India around 1500 BCE; the first of the three Vedas, it is the earliest extant text composed in Sanskrit, the language of ancient India."

- Ludden 2014, p. 19: "In Punjab, a dry region with grasslands watered by five rivers (hence 'panch' and 'ab') draining the western Himalayas, one prehistoric culture left no material remains, but some of its ritual texts were preserved orally over the millennia. The culture is called Aryan, and evidence in its texts indicates that it spread slowly south-east, following the course of the Yamuna and Ganga Rivers. Its elite called itself Arya (pure) and distinguished themselves sharply from others. Aryans led kin groups organized as nomadic horse-herding tribes. Their ritual texts are called Vedas, composed in Sanskrit. Vedic Sanskrit is recorded only in hymns that were part of Vedic rituals to Aryan gods. To be Aryan apparently meant to belong to the elite among pastoral tribes. Texts that record Aryan culture are not precisely datable, but they seem to begin around 1200 BCE with four collections of Vedic hymns (Rg, Sama, Yajur, and Artharva)."

- Dyson 2018, pp. 14–15: "Although the collapse of the Indus valley civilisation is no longer believed to have been due to an 'Aryan invasion' it is widely thought that, at roughly the same time, or perhaps a few centuries later, new Indo-Aryan-speaking people and influences began to enter the subcontinent from the north-west. Detailed evidence is lacking. Nevertheless, a predecessor of the language that would eventually be called Sanskrit was probably introduced into the north-west sometime between 3,900 and 3,000 years ago. This language was related to one then spoken in eastern Iran; and both of these languages belonged to the Indo-European language family. [...] It seems likely that various small-scale migrations were involved in the gradual introduction of the predecessor language and associated cultural characteristics. However, there may not have been a tight relationship between movements of people on the one hand, and changes in language and culture on the other. Moreover, the process whereby a dynamic new force gradually arose—a people with a distinct ideology who eventually seem to have referred to themselves as 'Arya'—was certainly two-way. That is, it involved a blending of new features which came from outside with other features—probably including some surviving Harappan influences—that were already present. Anyhow, it would be quite a few centuries before Sanskrit was written down. And the hymns and stories of the Arya people—especially the Vedas and the later Mahabharata and Ramayana epics—are poor guides as to historical events. Of course, the emerging Arya were to have a huge impact on the history of the subcontinent. Nevertheless, little is known about their early presence."

- Robb 2011, pp. 46–: "The expansion of Aryan culture is supposed to have begun around 1500 BCE. It should not be thought that this Aryan emergence (though it implies some migration) necessarily meant either a sudden invasion of new peoples, or a complete break with earlier traditions. It comprises a set of cultural ideas and practices, upheld by a Sanskrit-speaking elite, or Aryans. The features of this society are recorded in the Vedas."

- ^