Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

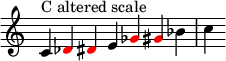

Altered scale

View on Wikipedia| Modes | I, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII |

|---|---|

| Component pitches | |

| C, D♭, E♭, F♭, G♭, A♭, B♭ | |

| Qualities | |

| Number of pitch classes | 7 |

| Forte number | 7-34 |

| Complement | 5-34 |

In jazz, the altered scale, altered dominant scale, or super-Locrian scale (Locrian ♭4 scale) is a seven-note scale that is a dominant scale where all non-essential tones have been altered. The triad formed from the root of the altered scale creates a diminished triad, but due to the inclusion of a diminished 11th, the scale comprises the three irreducibly essential tones that define a dominant seventh chord, which are root, major third, and minor seventh and that all other chord tones have been altered. These are:

- the fifth is altered to a ♭5

- the ninth is altered to a ♭9

- the eleventh is altered to a ♭11 (equivalent to a major third)

- the thirteenth is altered to a ♭13 (equivalent to a ♯5)

- and the minor third can be considered a ♯9

The altered forms of some of the non-essential tones coincide (augmented eleventh with diminished fifth and augmented fifth with minor thirteenth) meaning those scale degrees are enharmonically identical and have multiple potential spellings. The natural forms of the non-essential tones are absent in the scale, thus it lacks a major ninth, a perfect eleventh, a perfect fifth, and a major thirteenth.

This is written below in musical notation with the essential chord tones coloured black and the non-essential altered chord tones coloured red.

The altered scale is made by the sequence:

- Half, Whole, Half, Whole, Whole, Whole, Whole

The abbreviation "alt" (for "altered") used in chord symbols enhances readability by reducing the number of characters otherwise needed to define the chord and avoids the confusion of multiple equivalent complex names. For example, "C7alt" supplants "C7♯5♭9♯9♯11", "C7−5+5−9+9", "Caug7−9+9+11", etc.

This scale has existed for a long time as the 7th mode of the ascending melodic minor scale.

Enharmonic spellings and alternate names

[edit]The C altered scale is also enharmonically equivalent to the C Locrian mode with F changed to F♭. For this reason, the altered scale is sometimes called the Locrian ♭ 4 scale.[1]

It is also enharmonically the seventh mode of the ascending melodic minor scale. The altered scale is also known as the Pomeroy scale after Herb Pomeroy,[2][3] the Ravel scale after Maurice Ravel, and the diminished whole tone scale due to its resemblance to the lower part of the diminished scale and the upper part of the whole tone scale.[4]

The super-Locrian scale (enharmonically identical to the altered scale) is obtained by flattening the fourth note of the diatonic Locrian mode. For example, flattening the fourth note of the C Locrian scale gives us the C altered scale:

The altered scale can also be achieved by raising the tonic of a major scale by a half step. For instance, raising the tonic of the C major scale by a half step (here spelled as an augmented unison) produces the scale C♯-D-E-F-G-A-B-C♯:

The altered scale can also be the major scale with all of the notes except the tonic being flattened. For example, taking the C♯ major scale and flattening all of the notes except the tonic produces the C♯ altered scale (see above).

Common usage

[edit]Because it contains the essential notes of a dominant seventh chord, it can be used to create melodies over the dominant chord in a jazz context. The added dissonance of the altered notes creates extra tension on the dominant.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Service 1993, 28.

- ^ Bahha and Rawlins 2005, 33.

- ^ Miller 1996, 35.

- ^ Haerle 1975, 15.

Sources

- Bahha, Nor Eddine, and Robert Rawlins. 2005. Jazzology: The Encyclopedia of Jazz Theory for All Musicians, edited by Barrett Tagliarino. Milwaukee: Hal Leonard. ISBN 978-0-634-08678-6.

- Haerle, Dan. 1975. Scales for Jazz Improvisation: A Practice Method for All Instruments. Lebanon, Indiana: Studio P/R; Miami: Warner Bros.; Hialeah : Columbia Pictures Publications. ISBN 978-0-89898-705-8.

- Miller, Ron. 1996. Modal Jazz Composition & Harmony, volume 1. Rottenburg: Advance Music.

- Service, Saxophone. 1993. "The Altered Scale In Jazz Improvisation". Saxophone Journal 18, no. 4 (July–August):[full citation needed]

Further reading

[edit]- Callender, Clifton. 1998. "Voice-leading parsimony in the music of Alexander Scriabin", Journal of Music Theory 42, no. 2 ("Neo-Riemannian Theory", Autumn): 219–233.

- Tymoczko, Dmitri. 1997. "The Consecutive-Semitone Constraint on Scalar Structure: A Link Between Impressionism and Jazz." Integral 11:135–79.

- Tymoczko, Dmitri. 2004. "Scale Networks in Debussy." Journal of Music Theory 48, no. 2 (Autumn): 215–292.

External links

[edit]- "The Altered Scale for Jazz Guitar", jazzguitar.be