Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Scale (music)

View on Wikipedia

In music theory, a scale is "any consecutive series of notes that form a progression between one note and its octave", typically by order of pitch or fundamental frequency.[1][2]

The word "scale" originates from the Latin scala, which literally means "ladder". Therefore, any scale is distinguishable by its "step-pattern", or how its intervals interact with each other.[1][2]

Often, especially in the context of the common practice period, most or all of the melody and harmony of a musical work is built using the notes of a single scale, which can be conveniently represented on a staff with a standard key signature.[3]

Due to the principle of octave equivalence, scales are generally considered to span a single octave, with higher or lower octaves simply repeating the pattern. A musical scale represents a division of the octave space into a certain number of scale steps, a scale step being the recognizable distance (or interval) between two successive notes of the scale.[4] However, there is no need for scale steps to be equal within any scale and, particularly as demonstrated by microtonal music, there is no limit to how many notes can be injected within any given musical interval.

A measure of the width of each scale step provides a method to classify scales. For instance, in a chromatic scale each scale step represents a semitone interval, while a major scale is defined by the interval pattern W–W–H–W–W–W–H, where W stands for whole step (an interval spanning two semitones, e.g. from C to D), and H stands for half-step (e.g. from C to D♭). Based on their interval patterns, scales are put into categories including pentatonic, diatonic, chromatic, major, minor, and others.

A specific scale is defined by its characteristic interval pattern and by a special note, known as its first degree (or tonic). The tonic of a scale is the note selected as the beginning of the octave, and therefore as the beginning of the adopted interval pattern. Typically, the name of the scale specifies both its tonic and its interval pattern. For example, C major indicates a major scale with a C tonic.

Background

[edit]Scales, steps, and intervals

[edit]

Scales are typically listed from low to high pitch. Most scales are octave-repeating, meaning their pattern of notes is the same in every octave (the Bohlen–Pierce scale is one exception). An octave-repeating scale can be represented as a circular arrangement of pitch classes, ordered by increasing (or decreasing) pitch class. For instance, the increasing C major scale is C–D–E–F–G–A–B–[C], with the bracket indicating that the last note is an octave higher than the first note, and the decreasing C major scale is C–B–A–G–F–E–D–[C], with the bracket indicating an octave lower than the first note in the scale.

The distance between two successive notes in a scale is called a scale step.

The notes of a scale are numbered by their steps from the first degree of the scale. For example, in a C major scale the first note is C, the second D, the third E and so on. Two notes can also be numbered in relation to each other: C and E create an interval of a third (in this case a major third); D and F also create a third (in this case a minor third).

Pitch

[edit]A single scale can be manifested at many different pitch levels. For example, a C major scale can be started at C4 (middle C; see scientific pitch notation) and ascending an octave to C5; or it could be started at C6, ascending an octave to C7.

Types of scale

[edit]

Scales may be described according to the number of different pitch classes they contain:

- Chromatic, or dodecatonic (12 notes per octave)

- Nonatonic (9 notes per octave): a chromatic variation of the heptatonic blues scale

- Octatonic (8 notes per octave): used in jazz and modern classical music

- Heptatonic (7 notes per octave): the most common modern Western scale

- Hexatonic (6 notes per octave): common in Western folk music

- Pentatonic (5 notes per octave): the anhemitonic form (lacking semitones) is common in folk music, especially in Asian music; also known as the "black note" scale

- Tetratonic (4 notes), tritonic (3 notes), and ditonic (2 notes): generally limited to prehistoric ("primitive") music

Scales may also be described by their constituent intervals, such as being hemitonic, cohemitonic, or having imperfections.[5] Many music theorists concur that the constituent intervals of a scale have a large role in the cognitive perception of its sonority, or tonal character.

"The number of the notes that make up a scale as well as the quality of the intervals between successive notes of the scale help to give the music of a culture area its peculiar sound quality."[6] "The pitch distances or intervals among the notes of a scale tell us more about the sound of the music than does the mere number of tones."[7]

Scales may also be described by their symmetry, such as being palindromic, chiral, or having rotational symmetry as in Messiaen's modes of limited transposition.

Harmonic content

[edit]The notes of a scale form intervals with each of the other notes of the chord in combination. A 5-note scale has 10 of these harmonic intervals, a 6-note scale has 15, a 7-note scale has 21, an 8-note scale has 28, a scale with n notes has n(n-1)/2.[8] Though the scale is not a chord, and might never be heard more than one note at a time, still the absence, presence, and placement of certain key intervals plays a large part in the sound of the scale, the natural movement of melody within the scale, and the selection of chords taken naturally from the scale.[8]

A musical scale that contains tritones is called tritonic (though the expression is also used for any scale with just three notes per octave, whether or not it includes a tritone), and one without tritones is atritonic. A scale or chord that contains semitones is called hemitonic, and without semitones is anhemitonic.

Scales in composition

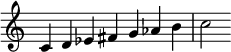

[edit]Scales can be abstracted from performance or composition. They are also often used precompositionally to guide or limit a composition. Explicit instruction in scales has been part of compositional training for many centuries. One or more scales may be used in a composition, such as in Claude Debussy's L'Isle Joyeuse.[9] To the right, the first scale is a whole-tone scale, while the second and third scales are diatonic scales. All three are used in the opening pages of Debussy's piece.

Western music

[edit]Scales in traditional Western music generally consist of seven notes and repeat at the octave. Notes in the commonly used scales (see just below) are separated by whole and half step intervals of tones and semitones. The harmonic minor scale includes a three-semitone step (an augmented second); the anhemitonic pentatonic includes two of those and no semitones.

Western music in the Medieval and Renaissance periods (1100–1600) tends to use the white-note diatonic scale C–D–E–F–G–A–B. Accidentals are rare, and somewhat unsystematically used, often to avoid the tritone.

Music of the common practice periods (1600–1900) uses four types of scales:

- The major and natural minor scales, known as the diatonic scales (seven notes)

- The harmonic and melodic minor scales (seven notes)

These scales are used in all of their transpositions. The music of this period introduces modulation, which involves systematic changes from one scale to another. Modulation occurs in relatively conventionalized ways. For example, major-mode pieces typically begin in a "tonic" diatonic scale and modulate to the "dominant" scale a fifth above.

In the 19th century (to a certain extent), but more in the 20th century, additional types of scales were explored:

- The chromatic scale (twelve notes)

- The whole-tone scale (six notes)

- The pentatonic scale (five notes)

- The octatonic or diminished scales (eight notes)

A large variety of other scales exists, some of the more common being:

- The Phrygian dominant scale (a mode of the harmonic minor scale)

- The Arabic scales

- The Hungarian minor scale

- The Byzantine music scales (called echoi)

- The Persian scale

Scales such as the pentatonic scale may be considered gapped relative to the diatonic scale. An auxiliary scale is a scale other than the primary or original scale. See: modulation (music) and Auxiliary diminished scale.

Note names

[edit]In many musical circumstances, a specific note of the scale is chosen as the tonic—the central and most stable note of the scale. In Western tonal music, simple songs or pieces typically start and end on the tonic note. Relative to a choice of a certain tonic, the notes of a scale are often labeled with numbers recording how many scale steps above the tonic they are. For example, the notes of the C major scale (C, D, E, F, G, A, B) can be labeled {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7}, reflecting the choice of C as tonic. The expression scale degree refers to these numerical labels. Such labeling requires the choice of a "first" note; hence scale-degree labels are not intrinsic to the scale itself, but rather to its modes. For example, if we choose A as tonic, then we can label the notes of the C major scale using A = 1, B = 2, C = 3, and so on. When we do so, we create a new scale called the A minor scale. See the musical note article for how the notes are customarily named in different countries.

The scale degrees of a heptatonic (7-note) scale can also be named using the terms tonic, supertonic, mediant, subdominant, dominant, submediant, subtonic. If the subtonic is a semitone away from the tonic, then it is usually called the leading-tone (or leading-note); otherwise the leading-tone refers to the raised subtonic. Also commonly used is the (movable do) solfège naming convention in which each scale degree is denoted by a syllable. In the major scale, the solfège syllables are: do, re, mi, fa, so (or sol), la, si (or ti), do (or ut).

In naming the notes of a scale, it is customary that each scale degree be assigned its own letter name: for example, the A major scale is written A–B–C♯–D–E–F♯–G♯ rather than A–B–D♭–D–E–E![]() –G♯. However, it is impossible to do this in scales that contain more than seven notes, at least in the English-language nomenclature system.[10]

–G♯. However, it is impossible to do this in scales that contain more than seven notes, at least in the English-language nomenclature system.[10]

Scales may also be identified by using a binary system of twelve zeros or ones to represent each of the twelve notes of a chromatic scale. The most common binary numbering scheme defines lower pitches to have lower numeric value (as opposed to low pitches having a high numeric value). Thus a single pitch class n in the pitch class set is represented by 2^n. This maps the entire power set of all pitch class sets in 12-TET to the numbers 0 to 4095. The binary digits read as ascending pitches from right to left, which some find discombobulating because they are used to low to high reading left to right, as on a piano keyboard. In this scheme, the major scale is 101010110101 = 2741. This binary representation permits easy calculation of interval vectors and common tones, using logical binary operators. It also provides a perfect index for every possible combination of tones, as every scale has its own number.[11][12]

Scales may also be shown as semitones from the tonic. For instance, 0 2 4 5 7 9 11 denotes any major scale such as C–D–E–F–G–A–B, in which the first degree is, obviously, 0 semitones from the tonic (and therefore coincides with it), the second is 2 semitones from the tonic, the third is 4 semitones from the tonic, and so on. Again, this implies that the notes are drawn from a chromatic scale tuned with 12-tone equal temperament. For some fretted string instruments, such as the guitar and the bass guitar, scales can be notated in tabulature, an approach which indicates the fret number and string upon which each scale degree is played.

Transposition and modulation

[edit]This section may be confusing or unclear to readers. In particular, transposition and modulation are different;. (August 2018) |

Composers transform musical patterns by moving every note in the pattern by a constant number of scale steps: thus, in the C major scale, the pattern C–D–E might be shifted up, or transposed, a single scale step to become D–E–F. This process is called "scalar transposition" or "shifting to a new key" and can often be found in musical sequences and patterns. (It is D–E–F♯ in Chromatic transposition). Since the steps of a scale can have various sizes, this process introduces subtle melodic and harmonic variation into the music. In Western tonal music, the simplest and most common type of modulation (or changing keys) is to shift from one major key to another key built on the first key's fifth (or dominant) scale degree. In the key of C major, this would involve moving to the key of G major (which uses an F♯). Composers also often modulate to other related keys. In some Romantic music era pieces and contemporary music, composers modulate to "remote keys" that are not related to or close to the tonic. An example of a remote modulation would be taking a song that begins in C major and modulating (changing keys) to F♯ major.

Jazz and blues

[edit]

Through the introduction of blue notes, jazz and blues employ scale intervals smaller than a semitone. The blue note is an interval that is technically neither major nor minor but "in the middle", giving it a characteristic flavour. A regular piano cannot play blue notes, but with electric guitar, saxophone, trombone and trumpet, performers can "bend" notes a fraction of a tone sharp or flat to create blue notes. For instance, in the key of E, the blue note would be either a note between G and G♯ or a note moving between both.

In blues, a pentatonic scale is often used. In jazz, many different modes and scales are used, often within the same piece of music. Chromatic scales are common, especially in modern jazz.

Non-Western scales

[edit]Equal temperament

[edit]In Western music, scale notes are often separated by equally tempered tones or semitones, creating 12 intervals per octave. Each interval separates two tones; the higher tone has an oscillation frequency of a fixed ratio (by a factor equal to the twelfth root of two, or approximately 1.059463) higher than the frequency of the lower one. A scale uses a subset consisting typically of 7 of these 12 as scale steps.

Other

[edit]Many other musical traditions use scales that include other intervals. These scales originate within the derivation of the harmonic series. Musical intervals are complementary values of the harmonic overtones series.[13] Many musical scales in the world are based on this system, except most of the musical scales from Indonesia and the Indochina Peninsulae, which are based on inharmonic resonance of the dominant metalophone and xylophone instruments.

Intra-scale intervals

[edit]Some scales use a different number of pitches. A common scale in Eastern music is the pentatonic scale, which consists of five notes that span an octave. For example, in the Chinese culture, the pentatonic scale is usually used for folk music and consists of C, D, E, G and A, commonly known as gong, shang, jue, chi and yu.[14][15]

Some scales span part of an octave; several such short scales are typically combined to form a scale spanning a full octave or more, and usually called with a third name of its own. The Turkish and Middle Eastern music has around a dozen such basic short scales that are combined to form hundreds of full-octave spanning scales. Among these scales Hejaz scale has one scale step spanning 14 intervals (of the middle eastern type found 53 in an octave) roughly similar to 3 semitones (of the western type found 12 in an octave), while Saba scale, another of these middle eastern scales, has 3 consecutive scale steps within 14 commas, i.e. separated by roughly one western semitone either side of the middle tone.

Gamelan music uses a small variety of scales including Pélog and Sléndro, none including equally tempered nor harmonic intervals. Indian classical music uses a moveable seven-note scale. Indian Rāgas often use intervals smaller than a semitone.[16] Turkish music Turkish makams and Arabic music maqamat may use quarter tone intervals.[17][page needed] In both rāgas and maqamat, the distance between a note and an inflection (e.g., śruti) of that same note may be less than a semitone.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Denyer, Ralph (30 November 1982). The Guitar Handbook. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 104.

- ^ a b "Scale | Definition, Music Theory, & Types | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 25 June 2024.

- ^ Benward, Bruce and Saker, Marilyn Nadine (2003). Music: In Theory and Practice, seventh edition: vol. 1, p. 25. Boston: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-294262-0.

- ^ Hewitt, Michael (2013). Musical Scales of the World, pp. 2–3. The Note Tree. ISBN 978-0-9575470-0-1.

- ^ "All The Scales". www.allthescales.org. Archived from the original on 15 October 2017. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

- ^ Nzewi, Meki, and Odyke Nzewi (2007), A Contemporary Study of Musical Arts. Pretoria: Centre for Indigenous Instrumental African Music and Dance. Volume 1 p. 34 ISBN 978-1-920051-62-4.

- ^ Nettl, Bruno, and Helen Myers (1976). Folk Music in the United States, p.39. ISBN 978-0-8143-1557-6.

- ^ a b Hanson, Howard. (1960) Harmonic Materials of Modern Music, pp.7ff. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts. LOC 58-8138.

- ^ Tymoczko, Dmitri (2004). "Scale Networks and Debussy" (PDF). Journal of Music Theory. 48 (2): 219–294 (254–264). doi:10.1215/00222909-48-2-219. ISSN 0022-2909. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 August 2017. Retrieved 18 July 2017..

- ^ "C Major Scale". All About Music Theory.com. Retrieved 12 September 2022.

- ^ Daniel Starr. ‘Sets, Invariance, and Partitions’. In: Journal of Music Theory 22.1 (1978), pp. 1–42

- ^ Alexander Brinkman. Pascal Programming for Music Research. University of Chicago Press, 1990.

- ^ Explanation of the origin of musical scales clarified by a string division method Archived 24 August 2012 at the Wayback Machine by Yuri Landman on furious.com

- ^ Wu, Dan; Li, Chao-Yi; Yao, De-Zhong (1 October 2013). "An ensemble with the chinese pentatonic scale using electroencephalogram from both hemispheres". Neuroscience Bulletin. 29 (5): 581–587. doi:10.1007/s12264-013-1334-y. ISSN 1995-8218. PMC 5561954. PMID 23604597.

- ^ Van Khê, Trân (1985). "Chinese Music and Musical Traditions of Eastern Asia". The World of Music. 27 (1): 78–90. ISSN 0043-8774. JSTOR 43562680.

- ^ Burns, Edwaard M. 1998. "Intervals, Scales, and Tuning.", p. 247. In The Psychology of Music, second edition, edited by Diana Deutsch, 215–264. New York: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-213564-4.

- ^ Zonis, Ella (1973). Classical Persian Music: An Introduction. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674134354.

Further reading

[edit]- Barbieri, Patrizio (2008). Enharmonic Instruments and Music, 1470–1900. Latina, Italy: Il Levante Libreria Editrice. ISBN 978-88-95203-14-0.

- Yamaguchi, Masaya (2006). The Complete Thesaurus of Musical Scales (revised ed.). New York: Masaya Music Services. ISBN 978-0-9676353-0-9.

External links

[edit]Scale (music)

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Basic Concepts

In music, a scale is defined as a sequence of pitches arranged in ascending or descending order of frequency, serving as the foundational framework for constructing melodies, harmonies, and overall musical structures.[8][1] This ordered collection typically spans an octave and provides a organized set of notes from which composers and performers draw to create tonal relationships. Scales differ from related concepts such as keys, which refer to the tonal center and hierarchy derived from a scale, and modes, which are rotations or variations of a scale starting from different pitches.[10] The origins of musical scales trace back to ancient civilizations, with significant developments in ancient Greek music theory around the 6th century BCE. Pythagoras, a Greek philosopher and mathematician, pioneered an early system of tuning based on simple numerical ratios derived from string lengths, such as 2:1 for the octave and 3:2 for the perfect fifth, which formed the basis for the Pythagorean scale.[11][12] This approach integrated mathematics with acoustics, influencing subsequent theoretical frameworks in Western music and evolving over centuries into more flexible systems like just intonation and equal temperament to accommodate diverse musical practices.[13] A key distinction exists between scales and chords: while scales present pitches in a successive, linear manner to outline melodic contours, chords involve multiple pitches sounded simultaneously to produce harmonic textures.[14][15] For example, the basic solfège sequence do-re-mi-fa-sol-la-ti-do demonstrates a simple ascending scale, where each note follows the previous in time, contrasting with a chord's vertical stacking of tones.[16] Scales are built from intervals—the distance between consecutive pitches—which provide the structural building blocks for their unique character.Intervals, Steps, and Scale Degrees

In music theory, an interval is defined as the distance between two pitches, typically measured in semitones within the equal-tempered system prevalent in Western music.[10] The semitone, or half step, represents the smallest interval in this system, equivalent to one-twelfth of an octave, while a whole step, or whole tone, comprises two semitones.[17] These basic intervals form the building blocks of scales, where larger intervals are constructed by combining them—for instance, a major third spans four semitones, and a perfect fifth spans seven.[18] Within scales, steps refer to the intervals between consecutive scale degrees, which alternate between whole steps (W) and half steps (H) to create characteristic patterns. For example, the major scale follows the specific sequence W-W-H-W-W-W-H, resulting in ascending intervals of two, two, one, two, two, two, and one semitone, respectively, from the tonic to the octave.[19] This pattern ensures a balanced progression of tension and resolution, with half steps providing points of heightened dissonance that propel the music forward, as seen in the narrow intervals between the third and fourth degrees (one semitone) and the seventh and eighth (one semitone).[17] In contrast, other scales may vary this alternation, but the whole and half step dichotomy remains fundamental to scalar construction in tonal music.[20] Scale degrees are the individual notes of a scale, numbered from 1 to 7 in heptatonic scales such as the diatonic, with the first degree designated as the tonic.[21] Each degree has a distinct functional role in establishing tonality: the tonic (degree 1) serves as the central point of rest and stability; the supertonic (2) and mediant (3) provide transitional support; the subdominant (4) introduces preparatory tension leading toward the dominant; the dominant (5) creates strong resolutional pull back to the tonic due to its leading-tone implications; the submediant (6) offers relative stability or modal color; and the leading tone (7) generates dissonance that resolves upward to the tonic.[10] These functions arise from the intervallic relationships within the scale—for instance, the dominant is a perfect fifth (seven semitones) above the tonic, enhancing its gravitational role, while the subdominant is a perfect fourth (five semitones) below the dominant.[22] The formula for intervals in a diatonic scale, exemplified by the major mode, specifies the semitone distances between consecutive degrees as follows: 1–2 (two semitones), 2–3 (two semitones), 3–4 (one semitone), 4–5 (two semitones), 5–6 (two semitones), 6–7 (two semitones), and 7–1 (one semitone, completing the octave).[19] This cumulative structure yields larger intervals such as the major second (1–3: four semitones) and perfect fourth (1–5: five semitones), which underpin harmonic progressions and melodic contours in Western composition.[17]Pitch, Octave, and Tuning Basics

In music, pitch refers to the perceptual attribute of a sound that enables it to be ordered on a frequency-related scale, distinguishing high and low tones based on the auditory system's processing of acoustic signals.[23] The scientific basis for pitch lies in the fundamental frequency of a sound wave, which is the lowest frequency of a periodic waveform and is measured in hertz (Hz), representing cycles per second; for instance, higher fundamental frequencies generally correspond to higher perceived pitches in pure tones.[24] This perception arises from the inner ear's spectral analysis, where the cochlea decomposes sound into frequency components, allowing the brain to interpret the dominant frequency as pitch.[25] The octave represents a fundamental interval in music, defined as the distance between two pitches where the higher one's fundamental frequency is exactly double that of the lower one, resulting in a sensation of equivalence despite the heightened tone.[26] For example, the note C4 has a standard frequency of approximately 261.63 Hz, while C5, one octave higher, is 523.25 Hz, illustrating this doubling effect in equal-tempered tuning based on the international concert pitch standard of A4 at 440 Hz.[27] This octave equivalence underpins scale structure, as pitches separated by octaves are treated as iterations of the same note class, facilitating the cyclic nature of musical patterns across registers.[28] Tuning systems establish the precise frequencies assigned to pitches within an octave to achieve consonant intervals. Equal temperament, the predominant system in Western music, divides the octave into 12 equal semitones, each with a frequency ratio of , allowing modulation across keys without retuning.[29] In contrast, just intonation derives intervals from simple whole-number ratios for purer consonance, such as the perfect fifth at 3:2 (approximately 1.5), which aligns more closely with the harmonic series but limits transposition.[29] These approaches balance perceptual harmony with practical versatility in performance. Musical scales exploit octave equivalence by repeating their pattern of intervals every octave, ensuring continuity across the pitch range while maintaining structural identity. In notation, octave displacement allows the same pitch class to be represented in different registers for readability or instrumental range, such as notating a high C as C5 instead of the equivalent C4 an octave lower, without altering its role in the scale.[30] This repetition enables scales to extend indefinitely, with higher or lower octaves reinforcing the foundational pattern through frequency multiples of powers of 2.[31]Classification of Scales

Diatonic and Heptatonic Scales

Heptatonic scales encompass any musical scale comprising seven distinct pitches within an octave, forming a broad category that appears across diverse global traditions. In Western music, they include the diatonic scales, while non-Western examples occur in African traditional music, where heptatonic structures often underpin melodic frameworks in griot performances and ensemble playing, and in Chinese music, where they supplement more prevalent pentatonic systems for added expressiveness.[32][33] These scales provide a framework for tonal organization, typically dividing the octave into intervals that create a sense of hierarchy among the notes. Diatonic scales represent a specific subset of heptatonic scales, characterized by seven distinct pitches per octave arranged with five whole steps and two half steps. This structure ensures a balanced progression that avoids the full chromatic spectrum, emphasizing stepwise motion within the selected tones. The interval pattern for the natural diatonic scale, such as the major scale, follows a semitone sequence of whole-whole-half-whole-whole-whole-half (W-W-H-W-W-W-H), which generates the familiar tonal relationships in much of Western art music.[34][35][36] Within diatonic scales, the minor variants introduce structural diversity while maintaining the heptatonic form. The natural minor scale alters the major pattern to whole-half-whole-whole-whole-half-whole (W-H-W-W-W-H-W), flattening the third, sixth, and seventh degrees relative to the major for a darker tonal quality. The harmonic minor raises the seventh degree by a half step, creating a stronger leading tone for resolution (W-H-W-W-W-H-W with raised seventh), which facilitates dominant-to-tonic progressions in harmony. The melodic minor further modifies this by raising both the sixth and seventh degrees in ascent (W-H-W-W-W-W-H), reverting to natural minor pitches in descent to smooth voice leading and avoid awkward intervals.[37][38][4] These variants preserve the diatonic essence of five whole steps and two half steps overall, adapting the scale's profile for melodic and harmonic contexts.Chromatic, Pentatonic, and Hexatonic Scales

The chromatic scale consists of all twelve pitches within an octave, arranged in ascending or descending order by semitones, providing the complete set of notes available in Western equal temperament.[39] For example, the ascending chromatic scale starting on C includes the notes C, C♯/D♭, D, D♯/E♭, E, F, F♯/G♭, G, G♯/A♭, A, A♯/B♭, and B, returning to the octave above.[34] This scale introduces pitches outside any single diatonic collection, creating opportunities for chromaticism that adds expressive color, tension, or smooth transitions between keys.[40] In composition and improvisation, the chromatic scale facilitates modulation by allowing direct semitonal shifts or the insertion of altered notes to heighten emotional intensity, as seen in Romantic-era works where it enhances harmonic ambiguity.[41] Pentatonic scales feature five notes per octave, omitting two scale degrees from the diatonic set to produce a more open, consonant sound characterized by stepwise motion and larger intervals like perfect fourths and fifths.[42] The major pentatonic scale, for instance, derives from the first, second, third, fifth, and sixth degrees of the major scale (e.g., in C major: C, D, E, G, A), while the minor pentatonic uses the first, third (flattened), fourth, fifth, and seventh (flattened) degrees (e.g., in A minor: A, C, D, E, G).[43] These structures create characteristic "gaps" that avoid the tritone, resulting in a stable, melodic framework suited to improvisation and theme development.[44] Pentatonic scales appear widely in folk traditions across cultures, such as Celtic and certain West African musics, where their simplicity supports memorable, singable melodies without strong implications of a tonal center.[45] Hexatonic scales encompass six notes per octave, offering symmetrical patterns that diverge from heptatonic norms and evoke ambiguous or floating tonalities.[46] A prominent example is the whole-tone scale, constructed entirely of whole steps (e.g., C, D, E, F♯, G♯, A♯, returning to C), which divides the octave into six equal parts and lacks a clear tonal hierarchy due to its symmetry. Another common hexatonic scale alternates semitones and minor thirds (e.g., C, C♯, E, F, A♭, A), maximizing major thirds for a bright, augmented quality.[47] These scales contribute to impressionistic effects by blurring traditional resolution, as in Claude Debussy's compositions where the whole-tone scale suggests dreamlike ambiguity and coloristic expansion.[48] In broader applications, hexatonic formations provide melodic tension and facilitate non-functional harmony, enhancing expressive freedom in modern and jazz contexts.[49]Modal and Synthetic Scales

Modal scales, also known as modes, are derived by rearranging the intervals of a diatonic scale, typically starting from different scale degrees while using the same set of seven pitches.[50] This rotation alters the sequence of whole and half steps, creating distinct melodic flavors without establishing a strong hierarchical tonic-dominant relationship as in major or minor scales.[50] For instance, the Ionian mode begins on the first degree of the diatonic scale and corresponds to the familiar major scale, while the Dorian mode starts on the second degree, resulting in a pattern equivalent to a natural minor scale with a raised sixth degree.[50] These rearrangements introduce modal ambiguity, where the tonal center is less emphatic, allowing for greater melodic flexibility and emotional nuance in composition.[50] The origins of modal concepts trace back to ancient Greek music theory, where modes, or harmoniai, were formalized as scalar frameworks named after regions or ethnic groups, such as Dorian (after the Dorians), Phrygian (after Phrygia), and Lydian (after Lydia).[51] Philosopher Aristoxenus, in the 4th century BCE, described these modes within a system based on tetrachords—four-note segments—and various genera (diatonic, chromatic, enharmonic), emphasizing their ethical and affective qualities rather than fixed pitch collections.[51] Although the exact interval structures of ancient Greek modes differ from modern interpretations, their names were revived during the Renaissance, when theorists like Heinrich Glarean reassigned them to rotations of the diatonic scale, incorporating additional modes such as Ionian and Aeolian to expand the medieval church modes into a twelve-mode system.[52] This revival integrated Greek nomenclature into Western theory, influencing modal usage in Renaissance polyphony and later genres like jazz and folk, where the distinct interval patterns evoke varied moods without relying on tonal resolution.[53] Synthetic scales, in contrast, are artificially constructed pitch collections designed for specific compositional or improvisational effects, often diverging from natural or diatonic derivations to achieve unique sonorities.[54] Composers create them by specifying successions of intervals that repeat every octave, allowing transposition across the chromatic spectrum while prioritizing rhythmic, lyrical, or harmonic goals over traditional scale families.[54] A prominent example is the altered scale, used in jazz over dominant seventh chords with alterations; starting on C, it follows the pattern 1–♭2–♭3–♭4–♭5–♯5–♭7 (e.g., C–D♭–E♭–F♭–G♭–A♭–B♭), derived as the seventh mode of the melodic minor scale and emphasizing tension through clustered half steps.[55] Another is the diminished scale, an octatonic collection alternating whole and half steps; the whole-half version (e.g., C–D–E♭–F–G♭–G♯–A–B) suits symmetric diminished chords, creating ambiguity in tonal center due to its repeating pattern every minor third.[55] Unlike modes, which retain diatonic roots and promote modal interchange, synthetic scales often feature heightened dissonance or symmetry, enabling effects like unresolved tension or exotic color while maintaining a defined root for harmonic application.[54]Scales in Western Music Theory

Major and Minor Scales

In Western music theory, the major and minor scales form the foundational tonal structures, providing the basis for harmony, melody, and key signatures in the common practice period. The major scale, also known as the Ionian mode in modal contexts, follows a specific interval pattern of whole step-whole step-half step-whole step-whole step-whole step-half step (W-W-H-W-W-W-H), which creates a bright and consonant sound. For instance, the C major scale consists of the notes C-D-E-F-G-A-B-C, with no sharps or flats in its key signature. This pattern ensures that the third scale degree is a major third above the tonic, contributing to its characteristic uplifting quality.[19][10] Major scales are often associated with emotions of happiness, resolution, and stability due to their intervallic structure, which supports consonant triads and resolves tension effectively in harmonic progressions. In contrast, minor scales evoke a sense of melancholy or tension, primarily because of the minor third between the tonic and the third scale degree. The natural minor scale, or Aeolian mode, uses the pattern W-H-W-W-H-W-W; for example, A minor includes A-B-C-D-E-F-G-A and shares the same key signature as C major. This form derives directly from the sixth degree of the major scale, emphasizing a darker tonal color without alterations.[10][56][57] To facilitate stronger resolutions in harmony, particularly for the dominant V chord, the harmonic minor scale raises the seventh degree by a half step, altering the pattern to W-H-W-W-H-W+H (where W+H denotes a whole step plus half step, or augmented second). In A harmonic minor, this yields A-B-C-D-E-F-G♯-A, enabling a major triad on the fifth scale degree (E major) for cadential purpose. The melodic minor scale further adjusts the sixth and seventh degrees ascending (W-H-W-W-W-W-H) to A-B-C-D-E-F♯-G♯-A, smoothing the melody toward the tonic while descending to the natural form (A-G-F-E-D-C-B-A) for familiarity with the natural minor. These variants maintain the minor tonic's emotional depth while adapting to functional needs in composition.[37][58] Relative minors share the same key signature as their major counterparts but begin on the sixth degree, such as A minor relative to C major, using identical pitches (C-D-E-F-G-A-B) but centering on A as tonic. Parallel minors, by contrast, share the same tonic as the major but employ a different signature, like C minor (C-D-E♭-F-G-A♭-B♭-C) versus C major, highlighting shifts in mode while preserving the root pitch. These relationships underscore the interconnectedness of major and minor tonalities. In functional harmony, major keys typically feature the I-IV-V progression (tonic-subdominant-dominant), as in C-F-G in C major, establishing stability through resolution from V to I. Minor keys adapt this to i-iv-v (or i-iv-V using harmonic minor), such as Am-Dm-Em in A minor, where the dominant provides tension leading back to the minor tonic, reinforcing the scale's expressive range. Key relationships like these can be visualized via the circle of fifths, which arranges scales by sharps and flats to show relative connections.[59][38][22]Common Western Modes

The common Western modes, also known as the diatonic modes, refer to the seven scales derived by starting on different degrees of the major scale, each with a distinct interval structure and sonic character. Their names originate from ancient Greek theory and were adapted in medieval church music, where modes like Dorian and Phrygian were used; Ionian and Aeolian were formalized by Heinrich Glarean in his 1547 treatise Dodecachordon, expanding the traditional system to twelve modes. The modern understanding of these seven as rotations of the major scale, emphasizing unique tonal colors, developed in the 20th century.[60] They are built using the same seven notes but reordered, creating unique patterns of whole steps (W) and half steps (H) that evoke specific emotional qualities. The modes are as follows, with their interval formulas relative to the tonic, brief characterizations relative to major or minor scales, and notable uses:- Ionian mode: Interval pattern W-W-H-W-W-W-H. This is identical to the major scale, characterized by its bright, stable, and consonant sound due to major thirds and perfect fifths from the tonic. It serves as the foundation for much tonal music but is included here as the starting point for modal rotations.[61]

- Dorian mode: Interval pattern W-H-W-W-W-H-W. A minor mode with a raised sixth degree, giving it a melancholic yet hopeful flavor compared to the natural minor, often described as somber or introspective. It appears in Renaissance polyphony for expressive motets and in modern contexts like modal jazz.[62]

- Phrygian mode: Interval pattern H-W-W-W-H-W-W. A minor mode with a lowered second degree, creating an exotic, tense, and intense atmosphere due to the half-step from the tonic. This mode was used in Renaissance church music to convey passion or lament and persists in film scores for dramatic tension, such as evoking Spanish or Middle Eastern influences.[63]

- Lydian mode: Interval pattern W-W-W-H-W-W-H. A major mode with a raised fourth degree, producing a dreamy, ethereal, or uplifting quality from the augmented fourth interval. Employed in Renaissance vocal works for airy textures, it features prominently in contemporary film and soundtrack composition to suggest wonder or suspension.[61]

- Mixolydian mode: Interval pattern W-W-H-W-W-H-W. A major mode with a lowered seventh degree, yielding a folk-like, bluesy, or rustic character that resolves less strongly than Ionian. It informed Renaissance dance music and polyphonic settings, and is common in rock and folk traditions as well as modern scores for earthy or celebratory scenes.

- Aeolian mode: Interval pattern W-H-W-W-H-W-W. Equivalent to the natural minor scale, it features a lowered third, sixth, and seventh, evoking sadness, introspection, or pathos through its minor tonality. Widely used in Renaissance polyphony for somber hymns and remains a staple in Western composition for emotional depth.[61]

- Locrian mode: Interval pattern H-W-W-H-W-W-W. A diminished mode with a lowered second, fifth, and sixth, resulting in an unstable, dissonant, and tense sound due to the tritone from the tonic. Rarely used in Renaissance polyphony owing to its instability but occasionally appears in modern film scores for ominous or unresolved effects.[61]