Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

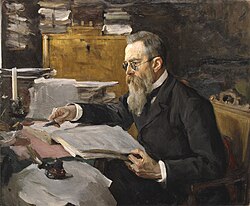

Composer

View on Wikipedia

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

A composer is a person who writes music.[1] The term is especially used to indicate composers of Western classical music,[2] or those who are composers by occupation.[3] Many composers are, or were, also skilled performers of music.

Etymology and definition

[edit]The term is descended from Latin, compōnō; literally "one who puts together".[4] The earliest use of the term in a musical context given by the Oxford English Dictionary is from Thomas Morley's 1597 A Plain and Easy Introduction to Practical Music, where he says "Some wil [sic] be good descanters [...] and yet wil be but bad composers".[1]

"Composer" is a loose term that generally refers to any person who writes music.[1] More specifically, it is often used to denote people who are composers by occupation,[3] or those who work in the tradition of Western classical music.[2] Writers of exclusively or primarily songs may be called composers, but since the 20th century the terms 'songwriter' or 'singer-songwriter' are more often used, particularly in popular music genres.[5] In other contexts, the term 'composer' can refer to a literary writer,[6] or more rarely and generally, someone who combines pieces into a whole.[7]

Across cultures and traditions composers may write and transmit music in a variety of ways. In much popular music, the composer writes a composition, and it is then transmitted via oral tradition. Conversely, in some Western classical traditions music may be composed aurally—i.e. "in the mind of the musician"—and subsequently written and passed through written documents.[8]

Role in the Western world

[edit]Relationship with performers

[edit]In the development of European classical music, the function of composing music initially did not have much greater importance than that of performing it.[citation needed] The preservation of individual compositions did not receive enormous attention and musicians generally had no qualms about modifying compositions for performance.

In the Western world, before the Romantic period of the 19th century, composition almost always went side by side with a combination of either singing, instructing and theorizing.[9]

Even in a conventional Western piece of instrumental music, in which all of the melodies, chords, and basslines are written out in musical notation, the performer has a degree of latitude to add artistic interpretation to the work, by such means as by varying their articulation and phrasing, choosing how long to make fermatas (held notes) or pauses, and — in the case of bowed string instruments, woodwinds or brass instruments — deciding whether to use expressive effects such as vibrato or portamento. For a singer or instrumental performer, the process of deciding how to perform music that has been previously composed and notated is termed "interpretation". Different performers' interpretations of the same work of music can vary widely, in terms of the tempos that are chosen and the playing or singing style or phrasing of the melodies. Composers and songwriters who present their music are interpreting, just as much as those who perform the music of others. The standard body of choices and techniques present at a given time and a given place is referred to as performance practice, whereas interpretation is generally used to mean the individual choices of a performer. [citation needed]

Although a musical composition often has a single author, this is not always the case. A work of music can have multiple composers, which often occurs in popular music when a band collaborates to write a song, or in musical theatre, where the songs may be written by one person, the orchestration of the accompaniment parts and writing of the overture is done by an orchestrator, and the words may be written by a third person.

A piece of music can also be composed with words, images, or, in the 20th and 21st centuries, computer programs that explain or notate how the singer or musician should create musical sounds. Examples of this range from wind chimes jingling in a breeze, to avant-garde music from the 20th century that uses graphic notation, to text compositions such as Aus den Sieben Tagen, to computer programs that select sounds for musical pieces. Music that makes heavy use of randomness and chance is called aleatoric music, and is associated with contemporary composers active in the 20th century, such as John Cage, Morton Feldman, and Witold Lutosławski.

The nature and means of individual variation of the music are varied, depending on the musical culture in the country and the time period it was written. For instance, music composed in the Baroque era, particularly in slow tempos, often was written in bare outline, with the expectation that the performer would add improvised ornaments to the melody line during a performance. Such freedom generally diminished in later eras, correlating with the increased use by composers of more detailed scoring in the form of dynamics, articulation, and so on; composers became uniformly more explicit in how they wished their music to be interpreted, although how strictly and minutely these are dictated varies from one composer to another. Because of this trend of composers becoming increasingly specific and detailed in their instructions to the performer, a culture eventually developed whereby faithfulness to the composer's written intention came to be highly valued (see, for example, Urtext edition). This musical culture is almost certainly related to the high esteem (bordering on veneration) in which the leading classical composers are often held by performers.

The historically informed performance movement has revived to some extent the possibility of the performer elaborating seriously the music as given in the score, particularly for Baroque music and music from the early Classical period. The movement might be considered a way of creating greater faithfulness to the original in works composed at a time that expected performers to improvise. In genres other than classical music, the performer generally has more freedom; thus for instance when a performer of Western popular music creates a "cover" of an earlier song, there is little expectation of exact rendition of the original; nor is exact faithfulness necessarily highly valued (with the possible exception of "note-for-note" transcriptions of famous guitar solos).

In Western art music, the composer typically orchestrates their compositions, but in musical theatre and pop music, songwriters may hire an arranger to do the orchestration. In some cases, a pop songwriter may not use notation at all, and, instead, compose the song in their mind and then play or record it from memory. In jazz and popular music, notable recordings by influential performers are given the weight that written scores play in classical music. The study of composition has traditionally been dominated by the examination of methods and practice of Western classical music, but the definition of composition is broad enough for the creation of popular and traditional music songs and instrumental pieces and to include spontaneously improvised works like those of free jazz performers and African percussionists such as Ewe drummers.

History of employment

[edit]During the Middle Ages, most composers worked for the Catholic church and composed music for religious services such as plainchant melodies. During the Renaissance music era, composers typically worked for aristocratic employers. While aristocrats typically required composers to produce a significant amount of religious music, such as Masses, composers also penned many non-religious songs on the topic of courtly love: the respectful, reverential love of a great woman from afar. Courtly love songs were very popular during the Renaissance era. During the Baroque music era, many composers were employed by aristocrats or as church employees. During the Classical period, composers began to organize more public concerts for profit, which helped composers to be less dependent on aristocratic or church jobs. This trend continued in the Romantic music era in the 19th century. In the 20th century, composers began to seek employment as professors in universities and conservatories. In the 20th century, composers also earned money from the sales of their works, such as sheet music publications of their songs or pieces or as sound recordings of their works.[citation needed]

Role of women

[edit]

In 1993, American musicologist Marcia Citron asked, "Why is music composed by women so marginal to the standard 'classical' repertoire?"[10] Citron "examines the practices and attitudes that have led to the exclusion of women composers from the received 'canon' of performed musical works." She argues that in the 1800s, women composers typically wrote art songs for performance in small recitals rather than symphonies intended for performance with an orchestra in a large hall, with the latter works being seen as the most important genre for composers; since women composers did not write many symphonies, they were deemed to be not notable as composers.[10]

According to Abbey Philips, "women musicians have had a very difficult time breaking through and getting the credit they deserve."[11] During the Medieval eras, most of the art music was created for liturgical (religious) purposes and due to the views about the roles of women that were held by religious leaders, few women composed this type of music, with the nun Hildegard von Bingen being among the exceptions. Most university textbooks on the history of music discuss almost exclusively the role of male composers. As well, very few works by women composers are part of the standard repertoire of classical music. In Concise Oxford History of Music, "Clara Shumann [sic] is one of the only female composers mentioned",[11] but other notable women composers of the common practice period include Fanny Mendelssohn and Cécile Chaminade, and arguably the most influential teacher of composers during the mid-20th century was Nadia Boulanger.[citation needed] Philips states that "[d]uring the 20th century the women who were composing/playing gained far less attention than their male counterparts."[11]

Women today are being taken more seriously in the realm of concert music, though the statistics of recognition, prizes, employment, and overall opportunities are still biased toward men.[12]

Modern training

[edit]Professional classical composers often have a background in performing classical music during their childhood and teens, either as a singer in a choir, as a player in a youth orchestra, or as a performer on a solo instrument (e.g., piano, pipe organ, or violin). Teens aspiring to be composers can continue their postsecondary studies in a variety of formal training settings, including colleges, conservatories, and universities. Conservatories, which are the standard musical training system in countries such as France and Canada, provide lessons and amateur orchestral and choral singing experience for composition students. Universities offer a range of composition programs, including bachelor's degrees, Master of Music degrees, and Doctor of Musical Arts degrees. As well, there are a variety of other training programs such as classical summer camps and festivals, which give students the opportunity to get coaching from composers.

Undergraduate

[edit]Bachelor's degrees in composition (referred to as B.Mus. or B.M) are four-year programs that include individual composition lessons, amateur orchestra/choral experience, and a sequence of courses in music history, music theory, and liberal arts courses (e.g., English literature), which give the student a more well-rounded education. Usually, composition students must complete significant pieces or songs before graduating. Not all composers hold a B.Mus. in composition; composers may also hold a B.Mus. in music performance or music theory.

Masters

[edit]Master of Music degrees (M.mus.) in composition consists of private lessons with a composition professor, ensemble experience, and graduate courses in music history and music theory, along with one or two concerts featuring the composition student's pieces. A master's degree in music (referred to as an M.Mus. or M.M.) is often a required minimum credential for people who wish to teach composition at a university or conservatory. A composer with an M.Mus. could be an adjunct professor or instructor at a university, but it would be difficult in the 2010s to obtain a tenure track professor position with this degree.

Doctoral

[edit]To become a tenure track professor, many universities require a doctoral degree. In composition, the key doctoral degree is the Doctor of Musical Arts, rather than the PhD; the PhD is awarded in music, but typically for subjects such as musicology and music theory.

Doctor of Musical Arts (referred to as D.M.A., DMA, D.Mus.A. or A.Mus.D) degrees in composition provide an opportunity for advanced study at the highest artistic and pedagogical level, requiring usually an additional 54+ credit hours beyond a master's degree (which is about 30+ credits beyond a bachelor's degree). For this reason, admission is highly selective. Students must submit examples of their compositions. If available, some schools will also accept video or audio recordings of performances of the student's pieces. Examinations in music history, music theory, ear training/dictation, and an entrance examination are required.

Students must prepare significant compositions under the guidance of faculty composition professors. Some schools require DMA composition students to present concerts of their works, which are typically performed by singers or musicians from the school. The completion of advanced coursework and a minimum B average are other typical requirements of a D.M.A program. During a D.M.A. program, a composition student may get experience teaching undergraduate music students.

Other routes

[edit]Some composers did not complete composition programs, but focused their studies on the performance of voice or an instrument or on music theory, and developed their compositional skills over the course of a career in another musical occupation.

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c OED: composer, 3..

- ^ a b "Composer". Collins English Dictionary. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- ^ a b Stevenson, Angus; Lindberg, Christine A., eds. (2015) [2010]. "Composer". New Oxford American Dictionary. ISBN 978-0-19-539288-3. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- ^ "compose (v.)". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- ^ Root, Deane L. (2001). "Songwriter". Grove Music Online. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.26215. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. (subscription, Wikilibrary access, or UK public library membership required)

- ^ OED: composer, 2..

- ^ OED: composer, 1..

- ^ Nettl 1983, p. 192.

- ^ Everist 2011, p. 2.

- ^ a b Citron, Marcia J. (1993). Gender and the Musical Canon. CUP Archive. ISBN 9780521392921.

- ^ a b c Philips, Abbey (1 September 2011). "The history of women and gender roles in music". Rvanews.com. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ^ Alex Ambrose (21 August 2014). "Her Music: Today's Emerging Female Composer". WQXR. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

General and cited sources

[edit]- Everist, Mark (2011). "Introduction". In Everist, Mark (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Medieval Music. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-316303-4.

- Nettl, Bruno (1983). The Study of Ethnomusicology: Twenty-nine Issues and Concepts. Champaign: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-01039-2.

- "composer, n". OED Online. Oxford: Oxford University Press. (subscription required)

Further reading

[edit]- Beckwith, John; Kasemets, Udo (1961). The Modern Composer and His World. Heritage. Foreword by Louis Applebaum. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-608-16267-6. JSTOR 10.3138/j.ctt15jjfcx.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Blum, Stephen (2023) [2001]. "Composition". Grove Music Online. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.06216. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. (subscription, Wikilibrary access, or UK public library membership required)

- Mugmon, Matthew (November 2013). "Beyond the Composer-Conductor Dichotomy: Bernstein's Copland-Inspired Mahler Advocacy". Music & Letters. 94 (4): 606–627. doi:10.1093/ml/gct131. JSTOR 24547378.

- Everist, Mark (2013). "Master and Disciple: Teaching the Composition of Polyphony in the Thirteenth Century". Musica Disciplina. 58: 51–71. JSTOR 24429413.

- Meyer, Leonard B. (2010). Music, the Arts, and Ideas: Patterns and Predictions in Twentieth-Century Culture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-52144-2.

- Piotrowska, Anna G. (December 2007). "Modernist Composers and the Concept of Genius / Skladatelji Moderne i pojam genija". International Review of the Aesthetics and Sociology of Music. 38 (2): 229–242. JSTOR 25487527.

- Wegman, Rob C. (Autumn 1996). "From Maker to Composer: Improvisation and Musical Authorship in the Low Countries, 1450-1500". Journal of the American Musicological Society. 49 (3): 409–479. doi:10.2307/831769. JSTOR 831769.

- Williams, Justin A.; Williams, Katherine, eds. (2016). The Cambridge Companion to the Singer-Songwriter. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-06364-8.

- Young, Toby (2024). "Introduction". In Young, Toby (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Composition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–18. ISBN 978-1-108-92373-6.

- Ziolkowski, Jan M. (2018). "1. The Composer". The Juggler of Notre Dame and the Medievalizing of Modernity. Vol. 4: Picture That: Making a Show of the Jongleur. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers. ISBN 978-1-01-329142-5. JSTOR j.ctv8d5t5s.