Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Minor scale

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2025) |

In Western classical music theory, the minor scale refers to three scale patterns – the natural minor scale (or Aeolian mode), the harmonic minor scale, and the melodic minor scale (ascending or descending).[1]

These scales contain all three notes of a minor triad: the root, a minor third (rather than the major third, as in a major triad or major scale), and a perfect fifth (rather than the diminished fifth, as in a diminished scale or half diminished scale).

Minor scale is also used to refer to other scales with this property,[2] such as the Dorian mode or the minor pentatonic scale (see other minor scales below).

Natural minor scale

[edit]Relationship to relative major

[edit]A natural minor scale (or Aeolian mode) is a diatonic scale that is built by starting on the sixth degree of its relative major scale. For instance, the A natural minor scale can be built by starting on the 6th degree of the C major scale:

Because of this, the key of A minor is called the relative minor of C major. Every major key has a relative minor, which starts on the 6th scale degree or step. For instance, since the 6th degree of F major is D, the relative minor of F major is D minor.

Relationship to parallel major

[edit]A natural minor scale can also be constructed by altering a major scale with accidentals. In this way, a natural minor scale is represented by the following notation:

- 1, 2, ♭3, 4, 5, ♭6, ♭7, 8

This notation is based on the major scale, and represents each degree (each note in the scale) by a number, starting with the tonic (the first, lowest note of the scale). By making use of flat symbols (♭) this notation thus represents notes by how they deviate from the notes in the major scale. Because of this, we say that a number without a flat represents a major (or perfect) interval, while a number with a flat represents a minor interval. In this example, the numbers mean:

- 1 = (perfect) unison

- 2 = major second

- ♭3 = minor third

- 4 = perfect fourth

- 5 = perfect fifth

- ♭6 = minor sixth

- ♭7 = minor seventh

- 8 = (perfect) octave

Thus, for instance, the A natural minor scale can be built by lowering the third, sixth, and seventh degrees of the A major scale by one semitone:

Because they share the same tonic note of A, the key of A minor is called the parallel minor of A major.

Intervals

[edit]

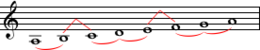

The intervals between the notes of a natural minor scale follow the sequence below:

- whole, half, whole, whole, half, whole, whole

where "whole" stands for a whole tone (a red u-shaped curve in the figure), and "half" stands for a semitone (a red angled line in the figure).

The natural minor scale is maximally even.

Harmonic minor scale

[edit]Construction

[edit]

The harmonic minor scale (or Aeolian ♮7 scale) has the same notes as the natural minor scale except that the seventh degree is raised by one semitone, creating an augmented second between the sixth and seventh degrees.

Thus, a harmonic minor scale is represented by the following notation:

- 1, 2, ♭3, 4, 5, ♭6, 7, 8

A harmonic minor scale can be built by lowering the 3rd and 6th degrees of the parallel major scale by one semitone.

Because of this construction, the 7th degree of the harmonic minor scale functions as a leading tone to the tonic because it is a semitone lower than the tonic, rather than a whole tone lower than the tonic as it is in natural minor scales.

Intervals

[edit]The intervals between the notes of a harmonic minor scale follow the sequence below:

- whole, half, whole, whole, half, augmented second, half

Uses

[edit]While it evolved primarily as a basis for chords, the harmonic minor with its augmented second is sometimes used melodically. Instances can be found in Mozart, Beethoven (for example, the finale of his String Quartet No. 14), and Schubert (for example, in the first movement of the Death and the Maiden Quartet). In this role, it is used while descending far more often than while ascending. A familiar example of the descending scale is heard in a ring of bells. A ring of twelve is sometimes augmented with a 5♯ and 6♭ to make a 10 note harmonic minor scale from bell 2 to bell 11 (for example, Worcester Cathedral).[4]

The Hungarian minor scale is similar to the harmonic minor scale but with a raised 4th degree. This scale is sometimes also referred to as "Gypsy Run", or alternatively "Egyptian Minor Scale", as mentioned by Miles Davis who describes it in his autobiography as "something that I'd learned at Juilliard".[5]

In popular music, examples of songs in harmonic minor include Katy B's "Easy Please Me", Bobby Brown's "My Prerogative", and Jazmine Sullivan's "Bust Your Windows". The scale also had a notable influence on heavy metal, spawning a sub-genre known as neoclassical metal, with guitarists such as Chuck Schuldiner, Yngwie Malmsteen, Ritchie Blackmore, and Randy Rhoads employing it in their music.[6]

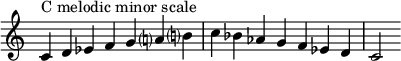

Melodic minor scale

[edit]Construction

[edit]The distinctive sound of the harmonic minor scale comes from the augmented second between its sixth and seventh scale degrees. While some composers have used this interval to advantage in melodic composition, others felt it to be an awkward leap, particularly in vocal music, and preferred a whole step between these scale degrees for smooth melody writing. To eliminate the augmented second, these composers either raised the sixth degree by a semitone or lowered the seventh by a semitone.

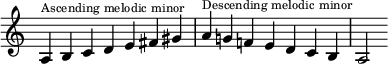

The melodic minor scale is formed by using both of these solutions. In particular, the raised sixth appears in the ascending form of the scale, while the lowered seventh appears in the descending form of the scale. Traditionally, these two forms are referred to as:

- the ascending melodic minor scale or jazz minor scale (also known as the Ionian ♭3 or Dorian ♮7): this form of the scale is also the 5th mode of the acoustic scale.

- the descending melodic minor scale: this form is identical to the natural minor scale .

The ascending and descending forms of the A melodic minor scale are shown below:

The ascending melodic minor scale can be notated as

- 1, 2, ♭3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8

while the descending melodic minor scale is

- 8, ♭7, ♭6, 5, 4, ♭3, 2, 1

Using these notations, the two melodic minor scales can be built by altering the parallel major scale.

Intervals

[edit]The intervals between the notes of an ascending melodic minor scale follow the sequence below:

- whole, half, whole, whole, whole, whole, half

The intervals between the notes of a descending melodic minor scale are the same as those of a descending natural minor scale.

Uses

[edit]![\relative c''' {

\set Staff.midiInstrument = #"violin"

\set Score.tempoHideNote = ##t \tempo 4 = 120

\key g \dorian

\time 4/4

g8^\markup \bold "Allegro"

f16 es d c bes a g a bes c d e fis g

fis8[ d]

}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/8/o/8owojgeebkd9l92qc54i7cs1s19knkd/8owojgee.png)

Composers have not been consistent in using the two forms of the melodic minor scale. Composers frequently require the lowered 7th degree found in the natural minor in order to avoid the augmented triad (III+) that arises in the ascending form of the scale.

Examples of the use of melodic minor in rock and popular music include Elton John's "Sorry Seems to Be the Hardest Word", which makes, "a nod to the common practice... by the use of F♯ [the leading tone in G minor] as the penultimate note of the final cadence."[7] The Beatles' "Yesterday" also partly uses the melodic minor scale.[citation needed]

Other minor scales

[edit]Other scales with a minor third and a perfect fifth (i.e. containing a minor triad) are also commonly referred to as minor scales.

Within the diatonic modes of the major scale, in addition to the Aeolian mode (which is the natural minor scale), the Dorian mode and the Phrygian mode also fall under this definition. Conversely, the Locrian mode has a minor third, but a diminished fifth (thus containing a diminished triad), and is therefore not commonly referred to as a minor scale.

The Hungarian minor scale is another heptatonic (7-note) scale referred to as minor.

The Jazz minor scale is a name for the melodic minor scale when only the "ascending form" is used.

Non-heptatonic scales may also be called "minor", such as the minor pentatonic scale.[8]

Limits of terminology

[edit]While any other scale containing a minor triad could be defined as a "minor scale", the terminology is less commonly used for some scales, especially those further outside the Western classical tradition.

The hexatonic (6-note) blues scale is similar to the minor pentatonic scale and fits the above definition. However, the flat fifth is present as a passing tone along with the perfect fifth, and the scale is often played with microtonal mixing of the major and minor thirds – thus making it harder to classify as a "major" or "minor" scale.

The two Neapolitan scales are both "minor scales" following the above definition, but were historically referred to as the "Neapolitan Major" or "Neapolitan Minor" based rather on the quality of their sixth degree.

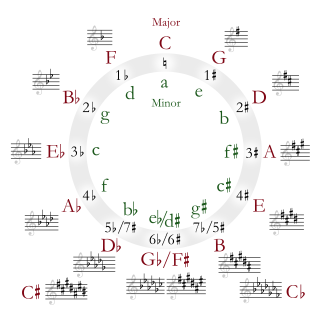

Key signature

[edit]In modern notation, the key signature for music in a minor key is typically based on the accidentals of the natural minor scale, not on those of the harmonic or melodic minor scales. For example, a piece in E minor will have one sharp in its key signature because the E natural minor scale has one sharp (F♯).

Major and minor keys that share the same key signature are relative to each other. For instance, F major is the relative major of D minor since both have key signatures with one flat. Since the natural minor scale is built on the 6th degree of the major scale, the tonic of the relative minor is a major sixth above the tonic of the major scale. For instance, B minor is the relative minor of D major because the note B is a major sixth above D. As a result, the key signatures of B minor and D major both have two sharps (F♯ and C♯).

Other notations and usage

[edit]When expressing the names of minor scale keys as abbreviations, the alphabet of the corresponding tonic note name can be written in lower case letters to indicate only the tonic note name. For example, when expressing the English notation of A minor, it can be abbreviated as 'a'. Plus, when expressing the names of major scale keys as abbreviations, the Roman alphabet of the corresponding tonic note is sometimes upper case to indicate only the tonic note name. For example, when expressing the English notation of C major, it is abbreviated as 'C'.[9]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Kostka, Stefan; Payne, Dorothy (2004). Tonal Harmony (5th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 12. ISBN 0-07-285260-7.

- ^ Prout, Ebenezer (1889). Harmony: Its Theory and Practice, pp. 15, 74, London, Augener.

- ^ a b Forte, Allen (1979). Tonal Harmony, p. 13. Third edition. Holt, Rinhart, and Winston. ISBN 0-03-020756-8.

- ^ "Dove's Guide"

- ^ Davis, Miles; Troupe, Quincy (1990). Miles, the Autobiography. Simon & Schuster. pp. 64. ISBN 0-671-72582-3.

- ^ "Neo-Classical Metal Music Genre Overview | AllMusic". AllMusic. Retrieved 2018-11-26.

- ^ Stephenson, Ken (2002). What to Listen for in Rock: A Stylistic Analysis. Yale University Press. p. 41. ISBN 9780300128239.

- ^ Bruce Benward and Marilyn Nadine Saker (2003), Music: In Theory and Practice, seventh edition (Boston: McGraw Hill), vol. I, p. 37. ISBN 978-0-07-294262-0.

- ^ "StackExchange - Questions - Capitalization of key names (C Minor vs. c minor)". Sep 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- Hewitt, Michael. 2013. Musical Scales of the World. The Note Tree. ISBN 978-0-9575470-0-1.

- Yamaguchi, Masaya. 2006. The Complete Thesaurus of Musical Scales, revised edition. New York: Masaya Music Services. ISBN 0-9676353-0-6.

External links

[edit]Minor scale

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and characteristics

The minor scale is a foundational seven-note diatonic scale in Western music theory, characterized by a minor third interval above the tonic, which sets it apart from the major scale and typically evokes a somber or melancholic mood.[2][5] This defining feature contributes to its emotional depth, often associated with sadness, introspection, or tension in musical expression.[6] As one of the two primary tonal scales alongside the major, it forms the basis for minor keys and is constructed from the natural minor pattern, influencing harmony, melody, and overall tonality in compositions.[3][4] The minor scale's prominence emerged in Western classical music during the Baroque era (approximately 1600–1750), when major and minor tonalities fully developed as structural pillars, allowing composers to convey complex emotions through key choices.[7] Johann Sebastian Bach, a key figure of this period, frequently employed minor scales in works like The Well-Tempered Clavier to explore harmonic progressions and affective contrasts.[8] Beyond classical traditions, the scale's cultural associations with melancholy persist in folk music and modern genres such as blues, where it underscores themes of longing and resilience.Scale degrees and basic intervals

In the minor scale, the seven scale degrees are identified by numbers from 1 to 7, each with a traditional name that reflects its position relative to the tonic: the first degree (1) is the tonic, the second (2) is the supertonic, the third (3) is the mediant, the fourth (4) is the subdominant, the fifth (5) is the dominant, the sixth (6) is the submediant, and the seventh (7) is the subtonic.[1][9] These names are consistent across diatonic scales, though the subtonic specifically denotes the lowered seventh degree in minor, which lies a whole step below the tonic rather than a half step.[10] The basic intervals from the tonic to each scale degree define the scale's structure: to the supertonic (2) is a major second (two semitones), to the mediant (3) is a minor third (three semitones), to the subdominant (4) is a perfect fourth (five semitones), to the dominant (5) is a perfect fifth (seven semitones), to the submediant (6) is a minor sixth (eight semitones), and to the subtonic (7) is a minor seventh (ten semitones).[11] These intervals arise from the cumulative semitone positions: 0 (tonic), 2, 3, 5, 7, 8, and 10.[12] The stepwise interval pattern of the minor scale, measured in whole steps (W, two semitones) and half steps (H, one semitone), is W-H-W-W-H-W-W, progressing from the tonic through the octave.[11] This pattern distinguishes the minor scale from the major scale (W-W-H-W-W-W-H) primarily through the positions of the half steps, resulting in lowered third, sixth, and seventh degrees relative to the parallel major scale (e.g., E♭, A♭, and B♭ instead of E, A, and B in C minor).[12] Scale degrees are notated using Arabic numerals with carets (e.g., , ) or Roman numerals for chords, often incorporating accidentals to indicate the flattened third (), sixth (), and seventh () degrees that characterize the minor quality.[1] For instance, in the key of A minor, the scale is A-B-C-D-E-F-G, with C (♭), F (♭), and G (♭) marked relative to the major.[11] While the natural minor uses these lowered degrees, the sixth and seventh may be raised in harmonic and melodic minor forms to create different interval relationships.[12]| Scale Degree | Name | Interval from Tonic | Semitones |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tonic | Unison | 0 |

| 2 | Supertonic | Major second | 2 |

| 3 | Mediant | Minor third | 3 |

| 4 | Subdominant | Perfect fourth | 5 |

| 5 | Dominant | Perfect fifth | 7 |

| 6 | Submediant | Minor sixth | 8 |

| 7 | Subtonic | Minor seventh | 10 |