Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Antisec Movement

View on WikipediaThe Anti Security Movement (also written as antisec and anti-sec) is a movement opposed to the computer security industry. Antisec is against full disclosure of information relating to software vulnerabilities, exploits, exploitation techniques, hacking tools, attacking public outlets and distribution points of that information. The general thought behind this is that the computer security industry uses full disclosure to profit and develop scare-tactics to convince people into buying their firewalls, anti-virus software and auditing services.

Key Information

Movement followers have identified as targets of their cause:

- websites such as SecurityFocus, SecuriTeam, Packet Storm, and milw0rm,

- mailing lists like "full-disclosure", "vuln-dev", "vendor-sec" and Bugtraq, and

- public forums and IRC channels.

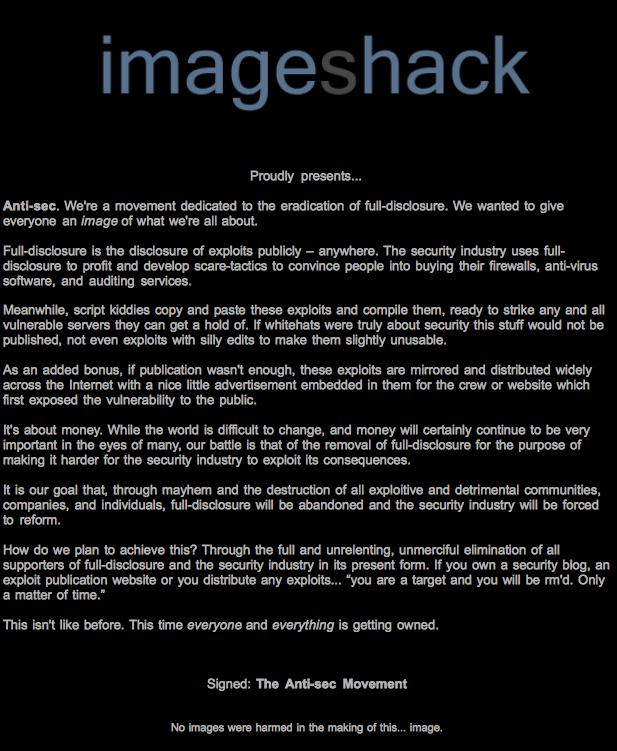

In 2009, attacks against security communities such as Astalavista[1] and milw0rm,[2] and the popular image-host ImageShack,[3][4] have given the movement worldwide media attention.

History

[edit]The start of most public attacks in the name of the anti-security movement started around 1999. The "anti-security movement" as it is understood today was coined by the following document which was initially an index on the anti.security.is website.[5][6][7][8]

The purpose of this movement is to encourage a new policy of anti-disclosure among the computer and network security communities. The goal is not to ultimately discourage the publication of all security-related news and developments, but rather, to stop the disclosure of all unknown or non-public exploits and vulnerabilities. In essence, this would put a stop to the publication of all private materials that could allow script kiddies from compromising systems via unknown methods.

The open-source movement has been an invaluable tool in the computer world, and we are all indebted to it. Open-source is a wonderful concept which should and will exist forever, as educational, scientific, and end-user software should be free and available to everybody.

Exploits, on the other hand, do not fall into this broad category. Just like munitions, which span from cryptographic algorithms to hand guns to missiles, and may not be spread without the control of export restrictions, exploits should not be released to a mass public of millions of Internet users. A digital holocaust occurs each time an exploit appears on Bugtraq, and kids across the world download it and target unprepared system administrators. Quite frankly, the integrity of systems world wide will be ensured to a much greater extent when exploits are kept private, and not published.

A common misconception is that if groups or individuals keep exploits and security secrets to themselves, they will become the dominators of the "illegal scene", as countless insecure systems will be solely at their mercy. This is far from the truth. Forums for information trade, such as Bugtraq, Packetstorm, www.hack.co.za, and vuln-dev have done much more to harm the underground and net than they have done to help them.

What casual browsers of these sites and mailing lists fail to realize is that some of the more prominent groups do not publish their findings immediately, but only as a last resort in the case that their code is leaked or has become obsolete. This is why production dates in header files often precede release dates by a matter of months or even years.

Another false conclusion by the same manner is that if these groups haven't released anything in a matter of months, it must be because they haven't found anything new. The regular reader must be made aware of these things.

We are not trying to discourage exploit development or source auditing. We are merely trying to stop the results of these efforts from seeing the light. Please join us if you would like to see a stop to the commercialization, media, and general abuse of infosec.

Thank you.

~el8

[edit]~el8 was one of the first anti-security hacktivist groups. The group waged war on the security industry with their popular assault known as "pr0j3kt m4yh3m". pr0j3kt m4yh3m was announced in the second issue of ~el8. The idea of the project was to eliminate all public outlets of security news and exploits. Some of ~el8's more notable targets included Theo de Raadt, K2, Mixter, Ryan Russel (Blue Boar), Gotfault (also known as INSANITY), Chris McNab (so1o), jobe, rloxley, pm, aempirei, broncbuster, lcamtuf, and OpenBSD's CVS repository.

The group published four electronic zines which are available on textfiles.com.[9]

pHC

[edit]pHC[10] is an acronym for "Phrack High Council". This group also waged war against the security industry and continued to update their website with news, missions, and hack logs.[11]

Less recent history

[edit]Most of the original groups such as ~el8 have grown tired of the anti-security movement and left the scene. New groups started to emerge.

dikline

[edit]dikline kept a website[12] which had an index of websites and people attacked by the group or submitted to them. Some of the more notable dikline targets were rave, rosiello, unl0ck, nocturnal, r0t0r, silent, gotfault, and skew/tal0n.[13]

More recent history

[edit]giest

[edit]In August 2008, mails were sent through the full-disclosure mailing list from a person/group known as "giest".

Other targets include mwcollect.org in which the group released a tar.gz containing listens of their honeypot networks.[14][15]

ZF0

[edit]ZF0 (Zer0 For Owned) performed multiple attacks in the name of pr0j3kt m4yh3m in 2009. They took targets such as Critical Security, Comodo and various others. They published 5 ezines in total.[16] July 2009, Kevin Mitnick's website was targeted by ZF0, displaying gay pornography with the text "all a board the mantrain."[17]

AntiSec Group

[edit]A group known as the "AntiSec Group"[18] enters the scene by attacking groups/communities such as an Astalavista,[1] a security auditing company named SSANZ and the popular image hosting website ImageShack.[3]

Graffiti reading "Antisec"[18] began appearing in San Diego, California in June 2011 and was incorrectly[19] associated with the original Antisec[18] movement. According to CBS8, a local TV affiliate "People living in Mission Beach say the unusual graffiti first appeared last week on the boardwalk." They also reported "...it was quickly painted over, but the stenciled words were back Monday morning." It was later realized[by whom?] to be related to the new Anti-Sec movement started by LulzSec and Anonymous.[20]

On April 30, 2015 the AntiSec Movement reappeared and started doxing police officers by hacking their databases. On April 30, 2015 they hacked into Madison Police Department and released officers names, address, phone numbers, and other personal data in relation to an Anonymous operation.[21][22]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Astalavista Hacked and Torn apart". Kotrotsos. Archived from the original on 8 June 2009. Retrieved July 7, 2009.

- ^ "Full Disclosure: Ant-Sec - We are going to terminate Hackforums.net and Milw0rm.com - New Apache 0-day exploit uncovered". Seclists.org. Retrieved 2012-08-20.

- ^ a b "ImageShack hacked in oddball security protest". The Register.

- ^ "ImageShack hacked by anti-full disclosure movement". ZDNet. Archived from the original on July 18, 2009.

- ^ "Anti Security :: Save a bug, save a life". 2001-03-01. Archived from the original on 2001-03-01. Retrieved 2012-08-20.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-07-20. Retrieved 2011-06-20.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-07-20. Retrieved 2011-06-20.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-07-20. Retrieved 2011-06-20.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "T E X T F I L E S". Web.textfiles.com. Retrieved 2012-08-20.

- ^ phrack.efnet.ru Archived April 2, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Index of /Backup/Oldschool/PHC". Archived from the original on 2009-07-20. Retrieved 2011-06-20.

- ^ "dikline.org". dikline.org. Archived from the original on 2012-11-07. Retrieved 2012-10-09.

- ^ [1] Archived October 20, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Security researchers' accounts ransacked in embarrasing [sic] hacklash". theregister.co.uk.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-07-21. Retrieved 2009-07-15.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Index of /ezines/ZF0". Gonullyourself.org. 2012-01-13. Archived from the original on 2012-05-12. Retrieved 2012-08-20.

- ^ "Mitnich website targeted". Theregister.co.uk. June 26, 2009.

- ^ a b c "antisecmovement.com". antisecmovement.com. Archived from the original on 2012-06-21. Retrieved 2012-10-09.

- ^ ""Anti-Sec" group spreads message through graffiti in Mission Beach". cbs8.com. 20 June 2011. Retrieved 2021-04-18.

- ^ "Unusual stenciled graffiti on Mission Beach boardwalk". WorldNow and Midwest Television. 20 June 2011. Archived from the original on February 10, 2012. Retrieved June 21, 2011.

- ^ #OpRobinson

- ^ Kopfstein, Janus (14 May 2015). "AntiSec Attacks Wisconsin Cops After Shooting Death of Unarmed Teen". Motherboard. Retrieved 10 June 2015.