Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Democratization

View on Wikipedia

| Part of the Politics series |

| Democracy |

|---|

|

|

Democratization, or democratisation, is the structural government transition from an authoritarian government to a more democratic political regime, including substantive political changes moving in a democratic direction.[1][2]

Whether and to what extent democratization occurs can be influenced by various factors, including economic development, historical legacies, civil society, and international processes. Some accounts of democratization emphasize how elites drove democratization, whereas other accounts emphasize grassroots bottom-up processes.[3] How democratization occurs has also been used to explain other political phenomena, such as whether a country goes to a war or whether its economy grows.[4]

The opposite process is known as democratic backsliding or autocratization.

Description

[edit]

Theories of democratization seek to explain a large macro-level change of a political regime from authoritarianism to democracy. Symptoms of democratization include reform of the electoral system, increased suffrage and reduced political apathy.

Measures of democratization

[edit]Democracy indices enable the quantitative assessment of democratization. Some common democracy indices are Freedom House, Polity data series, V-Dem Democracy indices and Democracy Index. Democracy indices can be quantitative or categorical. Some disagreements among scholars concern the concept of democracy and how to measure democracy – and what democracy indices should be used.

Waves of democratization

[edit]One way to summarize the outcome theories of democratization seek to account is with the idea of waves of democratization

A wave of democratization refers to a major surge of democracy in history. Samuel P. Huntington identified three waves of democratization that have taken place in history.[6] The first one brought democracy to Western Europe and North America in the 19th century. It was followed by a rise of dictatorships during the Interwar period. The second wave began after World War II, but lost steam between 1962 and the mid-1970s. The latest wave began in 1974 and is still ongoing. Democratization of Latin America and the former Eastern Bloc is part of this third wave.

Waves of democratization can be followed by waves of de-democratization. Thus, Huntington, in 1991, offered the following depiction.

• First wave of democratization, 1828–1926

• First wave of de-democratization, 1922–42

• Second wave of democratization, 1943–62

• Second wave of de-democratization, 1958–75

• Third wave of democratization, 1974–

The idea of waves of democratization has also been used and scrutinized by many other authors, including Renske Doorenspleet,[7] John Markoff,[8] Seva Gunitsky,[9] and Svend-Erik Skaaning.[10]

According to Seva Gunitsky, from the 18th century to the Arab Spring (2011–2012), 13 democratic waves can be identified.[9]

The V-Dem Democracy Report identified for the year 2023 9 cases of stand-alone democratization in East Timor, The Gambia, Honduras, Fiji, Dominican Republic, Solomon Islands, Montenegro, Seychelles, and Kosovo and 9 cases of U-Turn Democratization in Thailand, Maldives, Tunisia, Bolivia, Zambia, Benin, North Macedonia, Lesotho, and Brazil.[11]

By country

[edit]| Part of the Politics series on |

| Republicanism |

|---|

|

|

Throughout the history of democracy, enduring democracy advocates succeed almost always through peaceful means when there is a window of opportunity. One major type of opportunity include governments weakened after a violent shock.[12] The other main avenue occurs when autocrats are not threatened by elections, and democratize while retaining power.[13] The path to democracy can be long with setbacks along the way.[14][15][16]

Athens

[edit]Benin

[edit]Brazil

[edit]

Chile

[edit]France

[edit]The French Revolution (1789) briefly allowed a wide franchise. The French Revolutionary Wars and the Napoleonic Wars lasted for more than twenty years. The French Directory was more oligarchic. The First French Empire and the Bourbon Restoration restored more autocratic rule. The French Second Republic had universal male suffrage but was followed by the Second French Empire. The Franco-Prussian War (1870–71) resulted in the French Third Republic.

Germany

[edit]Germany established its first democracy in 1919 with the creation of the Weimar Republic, a parliamentary republic created following the German Empire's defeat in World War I. The Weimar Republic lasted only 14 years before it collapsed and was replaced by Nazi dictatorship.[26] Historians continue to debate the reasons why the Weimar Republic's attempt at democratization failed.[26] After Germany was militarily defeated in World War II, democracy was reestablished in West Germany during the U.S.-led occupation which undertook the denazification of society.[27]

United Kingdom

[edit]

In Great Britain, there was renewed interest in Magna Carta in the 17th century.[28] The Parliament of England enacted the Petition of Right in 1628 which established certain liberties for subjects. The English Civil War (1642–1651) was fought between the King and an oligarchic but elected Parliament,[29] during which the idea of a political party took form with groups debating rights to political representation during the Putney Debates of 1647.[30] Subsequently, the Protectorate (1653–59) and the English Restoration (1660) restored more autocratic rule although Parliament passed the Habeas Corpus Act in 1679, which strengthened the convention that forbade detention lacking sufficient cause or evidence. The Glorious Revolution in 1688 established a strong Parliament that passed the Bill of Rights 1689, which codified certain rights and liberties for individuals.[31] It set out the requirement for regular parliaments, free elections, rules for freedom of speech in Parliament and limited the power of the monarch, ensuring that, unlike much of the rest of Europe, royal absolutism would not prevail.[32][33] Only with the Representation of the People Act 1884 did a majority of the males get the vote.

Greece

[edit]Indonesia

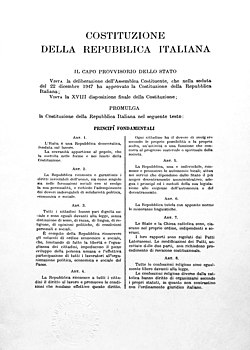

[edit]Italy

[edit]

In September 1847, violent riots inspired by Liberals broke out in Reggio Calabria and in Messina in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, which were put down by the military. On 12 January 1848 a rising in Palermo spread throughout the island and served as a spark for the Revolutions of 1848 all over Europe. After similar revolutionary outbursts in Salerno, south of Naples, and in the Cilento region which were backed by the majority of the intelligentsia of the Kingdom, on 29 January 1848 King Ferdinand II of the Two Sicilies was forced to grant a constitution, using for a pattern the French Charter of 1830. This constitution was quite advanced for its time in liberal democratic terms, as was the proposal of a unified Italian confederation of states.[34] On 11 February 1848, Leopold II of Tuscany, first cousin of Emperor Ferdinand I of Austria, granted the Constitution, with the general approval of his subjects. The Habsburg example was followed by Charles Albert of Sardinia (Albertine Statute; later became the constitution of the unified Kingdom of Italy and remained in force, with changes, until 1948[35]) and by Pope Pius IX (Fundamental Statute). However, only King Charles Albert maintained the statute even after the end of the riots.

The Kingdom of Italy, after the unification of Italy in 1861, was a constitutional monarchy. The new kingdom was governed by a parliamentary constitutional monarchy dominated by liberals.[a] The Italian Socialist Party increased in strength, challenging the traditional liberal and conservative establishment. From 1915 to 1918, the Kingdom of Italy took part in World War I on the side of the Entente and against the Central Powers. In 1922, following a period of crisis and turmoil, the Italian fascist dictatorship was established. During World War II, Italy was first part of the Axis until it surrendered to the Allied powers (1940–1943) and then, as part of its territory was occupied by Nazi Germany with fascist collaboration, a co-belligerent of the Allies during the Italian resistance and the subsequent Italian Civil War, and the liberation of Italy (1943–1945). The aftermath of World War II left Italy also with an anger against the monarchy for its endorsement of the Fascist regime for the previous twenty years. These frustrations contributed to a revival of the Italian republican movement.[36] Italy became a republic after the 1946 Italian institutional referendum[37] held on 2 June, a day celebrated since as Festa della Repubblica. Italy has a written democratic constitution, resulting from the work of a Constituent Assembly formed by the representatives of all the anti-fascist forces that contributed to the defeat of Nazi and Fascist forces during the liberation of Italy and the Italian Civil War,[38] and coming into force on 1 January 1948.

Japan

[edit]In Japan, limited democratic reforms were introduced during the Meiji period (when the industrial modernization of Japan began), the Taishō period (1912–1926), and the early Shōwa period.[39] Despite pro-democracy movements such as the Freedom and People's Rights Movement (1870s and 1880s) and some proto-democratic institutions, Japanese society remained constrained by a highly conservative society and bureaucracy.[39] Historian Kent E. Calder notes that writers that "Meiji leadership embraced constitutional government with some pluralist features for essentially tactical reasons" and that pre-World war II Japanese society was dominated by a "loose coalition" of "landed rural elites, big business, and the military" that was averse to pluralism and reformism.[39] While the Imperial Diet survived the impacts of Japanese militarism, the Great Depression, and the Pacific War, other pluralistic institutions, such as political parties, did not. After World War II, during the Allied occupation, Japan adopted a much more vigorous, pluralistic democracy.[39]

Madagascar

[edit]Malawi

[edit]| Part of a series on |

|---|

|

|

|

Latin America

[edit]Countries in Latin America became independent between 1810 and 1825, and soon had some early experiences with representative government and elections. All Latin American countries established representative institutions soon after independence, the early cases being those of Colombia in 1810, Paraguay and Venezuela in 1811, and Chile in 1818.[42] Adam Przeworski shows that some experiments with representative institutions in Latin America occurred earlier than in most European countries.[43] Mass democracy, in which the working class had the right to vote, become common only in the 1930s and 1940s.[44]

Portugal

[edit]Philippines

[edit]

In 1986, democratic institutions throughout the Philippines were reinstated during the deposition of the 20-year long Marcos regime through the People Power Revolution.

Barred constitutionally from running a third term by 1973, Ferdinand Marcos Sr. and his administration announced Proclamation No. 1081 on September 23, 1972, a declaration of martial law that deliberately decreed emergency powers over every democratic functions in the country, ostensibly under the pretext of a communist overthrow. Throughout the 20-year long martial law, most civil liberties of the once democratic Philippines were suppressed, criminalized, or just plainly abolished. By 1981, the loan-reliant economy of the Marcos regime experienced unforecasted contractions when the Reagan administration announced the lowering of American interest rates during the global recession at that time, further plunging the Philippine economy into debt.

In 1983, Benigno Aquino Jr., a renowned dissident of the Marcos regime, returned to the Philippines after his self-exile in the United States. After disembarking China Airlines Flight 811 on Gate 8 at Manila International Airport, Aquino, on the service steps of his van guarded by the Aviation Security Command (AVESCOM), was shot multiple times by assailants outside the van at point blank. He died from his wounds on the way to Fort Bonifacio Hospital.

In response to the assassination of Aquino, public outrage revitalized in the form of Jose W. Diokno's nationalist liberal democrat umbrella organization, the Kilusan sa Kapangyarihan at Karapatan ng Bayan or KAAKBAY, then leading the Justice for Aquino Justice for All or JAJA movement. JAJA consisted of the social democrat-dominant August Twenty One Movement or the ATOM, led by Butz Aquino. These political movements and organizations coalesced into the Kongreso ng Mamamayang Pilipino or KOMPIL, a call for parliamentarianism and democratization during this period. In the middle of 1984, JAJA was replaced by the Coalition for the Restoration of Democracy (CORD), with largely the same principles.

In November of 1985, the rapid development of opposition organizations swayed the Marcos administration, with some American intervention, to announce the Batas Pambansa Blg. 883 (National Law No. 883), a 1986 snap election, by the unicameral body, the Regular Batasang Pambansa. Immediately after the decree, the United Nationalist Democratic Organization (UNIDO), the main opposition multi-party electoral alliance, rallied even more public support, headed by assigned party leader Corazon "Cory" Cojuangco Aquino, Benigno Aquino's wife, and Salvador "Doy" Ramon Hidalgo Laurel.

The 1986 snap election was marred with electoral fraud, as discrepant figures from both the government-sponsored election canvasser, Commission on Elections (COMELEC), and the publicly-accredited poll watcher, National Movement for Free Elections (NAMFREL), finalized different tally figures. COMELEC announced a Marcos victory of 10,810,000 votes against Aquino's 9,300,000, while NAMFREL announced an Aquino victory of 7,840,000 votes against Marcos' 7,050,000. The apparent tampered snap election stirred public unrest, even prompting COMELEC technicians to proceed with a walkout mid-voting, an event cited to be the first act of civil disobedience during the People Power Revolution.

Occurring afterwards were a series of popular demonstrations against the regime occurring from February 22 to 26, referred to as the People Power Revolution, then culminating into the departure of Marcos and the non-violent transition of power, restoring democracy under Aquino's UNIDO. Immediately after Aquino's ascension, she ratified Proclamation No. 3, a law declaring a provisional constitution and government. The promulgation of the 1986 Freedom Constitution superseded many of the autocratic provisions of the 1973 Constitution, abolishing the Regular Batasang Pambansa, along with plebiscitarian dependence for the creation of a new Congress. The official adoption of the 1987 Constitution signalled the completion of Philippine democratization.

Senegal

[edit]Spain

[edit]The Spanish transition to democracy, known in Spain as la Transición (IPA: [la tɾansiˈθjon]; 'the Transition') or la Transición española ('the Spanish Transition'), is a period of modern Spanish history encompassing the regime change that moved from the Francoist dictatorship to the consolidation of a parliamentary system, in the form of constitutional monarchy under Juan Carlos I.

The democratic transition began two days after the death of Francisco Franco, in November 1975.[45] Initially, "the political elites left over from Francoism" attempted "reform of the institutions of dictatorship" through existing legal means,[46] but social and political pressure saw the formation of a democratic parliament in the 1977 general election, which had the imprimatur to write a new constitution that was then approved by referendum in December 1978. The following years saw the beginning of the development of the rule of law and establishment of regional government, amidst ongoing terrorism, an attempted coup d'état and global economic problems.[46] The Transition is said to have concluded after the landslide victory of the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE) in the 1982 general election and the first peaceful transfer of executive power.[46][b]South Africa

[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Apartheid |

|---|

|

South Korea

[edit]

Soviet Union

[edit]Switzerland

[edit]Roman Republic

[edit]Tunisia

[edit]Ukraine

[edit]United States

[edit]The American Revolution (1765–1783) created the United States. The new Constitution established a relatively strong federal national government that included an executive, a national judiciary, and a bicameral Congress that represented states in the Senate and the population in the House of Representatives.[58][59] In many fields, it was a success ideologically in the sense that a true republic was established that never had a single dictator, but voting rights were initially restricted to white male property owners (about 6% of the population).[60] Slavery was not abolished in the Southern states until the constitutional Amendments of the Reconstruction era following the American Civil War (1861–1865). The provision of Civil Rights for African-Americans to overcome post-Reconstruction Jim Crow segregation in the South was achieved in the 1960s.

Causes and factors

[edit]There is considerable debate about the factors which affect (e.g., promote or limit) democratization.[61] Factors discussed include economic, political, cultural, individual agents and their choices, international and historical.

Economic factors

[edit]Economic development and modernization theory

[edit]

Scholars such as Seymour Martin Lipset;[62] Carles Boix, Susan Stokes,[63]Dietrich Rueschemeyer, Evelyne Stephens, and John Stephens[64] argue that economic development increases the likelihood of democratization. Initially argued by Lipset in 1959, this has subsequently been referred to as modernization theory.[65][66] According to Daniel Treisman, there is "a strong and consistent relationship between higher income and both democratization and democratic survival in the medium term (10–20 years), but not necessarily in shorter time windows."[67] Robert Dahl argued that market economies provided favorable conditions for democratic institutions.[68]

A higher GDP/capita correlates with democracy. Some Who? claim the wealthiest democracies have never been observed to fall into authoritarianism.[69] The rise of Hitler and of the Nazis in Weimar Germany can be seen as an obvious counter-example. Although, in early 1930s, Germany was already an advanced economy. By that time, the country was also living in a state of economic crisis virtually since the first World War (in the 1910s). A crisis that was eventually worsened by the effects of the Great Depression. There is also the general observation that democracy was very rare before the industrial revolution. Empirical research thus led many to believe that economic development either increases chances for a transition to democracy, or helps newly established democracies consolidate.[69][70]

One study finds that economic development prompts democratization but only in the medium run (10–20 years). This is because development may entrench the incumbent leader while making it more difficult for him deliver the state to a son or trusted aide when he exits.[71] However, the debate about whether democracy is a consequence of wealth is far from conclusive.[72]

Another study suggests that economic development depends on the political stability of a country to promote democracy.[73] Clark, Robert and Golder, in their reformulation of Albert Hirschman's model of Exit, Voice and Loyalty, explain how it is not the increase of wealth in a country per se which influences a democratization process, but rather the changes in the socio-economic structures that come together with the increase of wealth. They explain how these structural changes have been called out to be one of the main reasons several European countries became democratic. When their socioeconomic structures shifted because modernization made the agriculture sector more efficient, bigger investments of time and resources were used for the manufacture and service sectors. In England, for example, members of the gentry began investing more in commercial activities that allowed them to become economically more important for the state. These new kinds of productive activities came with new economic power. Their assets became more difficult for the state to count and hence, more difficult to tax. Because of this, predation was no longer possible and the state had to negotiate with the new economic elites to extract revenue. A sustainable bargain had to be reached because the state became more dependent on its citizens remaining loyal, and with this, citizens now had the leverage to be taken into account in the decision making process for the country.[74][unreliable source?][75]

Adam Przeworski and Fernando Limongi argue that while economic development makes democracies less likely to turn authoritarian, there is insufficient evidence to conclude that development causes democratization (turning an authoritarian state into a democracy).[76] Economic development can boost public support for authoritarian regimes in the short-to-medium term.[77] Andrew J. Nathan argues that China is a problematic case for the thesis that economic development causes democratization.[78] Michael Miller finds that development increases the likelihood of "democratization in regimes that are fragile and unstable, but makes this fragility less likely to begin with."[79]

There is research to suggest that greater urbanization, through various pathways, contributes to democratization.[80][81]

Numerous scholars and political thinkers have linked a large middle class to the emergence and sustenance of democracy,[68][82] whereas others have challenged this relationship.[83]

In "Non-Modernization" (2022), Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson argue that modernization theory cannot account for various paths of political development "because it posits a link between economics and politics that is not conditional on institutions and culture and that presumes a definite endpoint—for example, an 'end of history'."[84]

A meta-analysis by Gerardo L. Munck of research on Lipset's argument shows that a majority of studies do not support the thesis that higher levels of economic development leads to more democracy.[85]

A 2024 study linked industrialization to democratization, arguing that large-scale employment in manufacturing made mass mobilization easier to occur and harder to repress.[86]

Capital mobility

[edit]Theories on causes to democratization such as economic development focuses on the aspect of gaining capital. Capital mobility focuses on the movement of money across borders of countries, different financial instruments, and the corresponding restrictions. In the past, there have been multiple theories as to what the relationship is between capital mobility and democratization.[87]

The "doomsway view" is that capital mobility is an inherent threat to underdeveloped democracies by the worsening of economic inequalities, favoring the interests of powerful elites and external actors over the rest of society. This might lead to depending on money from outside, therefore affecting the economic situation in other countries. Sylvia Maxfield argues that a bigger demand for transparency in both the private and public sectors by some investors can contribute to a strengthening of democratic institutions and can encourage democratic consolidation.[88]

A 2016 study found that preferential trade agreements can increase democratization of a country, especially trading with other democracies.[89] A 2020 study found increased trade between democracies reduces democratic backsliding, while trade between democracies and autocracies reduces democratization of the autocracies.[90] Trade and capital mobility often involve international organizations, such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Bank, and World Trade Organization (WTO), which can condition financial assistance or trade agreements on democratic reforms.[91]

Classes, cleavages and alliances

[edit]

Sociologist Barrington Moore Jr., in his influential Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy (1966), argues that the distribution of power among classes – the peasantry, the bourgeoise and the landed aristocracy – and the nature of alliances between classes determined whether democratic, authoritarian or communist revolutions occurred.[92] Moore also argued there were at least "three routes to the modern world" – the liberal democratic, the fascist, and the communist – each deriving from the timing of industrialization and the social structure at the time of transition. Thus, Moore challenged modernization theory, by stressing that there was not one path to the modern world and that economic development did not always bring about democracy.[93]

Many authors have questioned parts of Moore's arguments. Dietrich Rueschemeyer, Evelyne Stephens, and John D. Stephens, in Capitalist Development and Democracy (1992), raise questions about Moore's analysis of the role of the bourgeoisie in democratization.[94] Eva Bellin argues that under certain circumstances, the bourgeoise and labor are more likely to favor democratization, but less so under other circumstances.[95] Samuel Valenzuela argues that, counter to Moore's view, the landed elite supported democratization in Chile.[96] A comprehensive assessment conducted by James Mahoney concludes that "Moore's specific hypotheses about democracy and authoritarianism receive only limited and highly conditional support."[97]

A 2020 study linked democratization to the mechanization of agriculture: as landed elites became less reliant on the repression of agricultural workers, they became less hostile to democracy.[98]

According to political scientist David Stasavage, representative government is "more likely to occur when a society is divided across multiple political cleavages."[99] A 2021 study found that constitutions that emerge through pluralism (reflecting distinct segments of society) are more likely to induce liberal democracy (at least, in the short term).[100]

Political-economic factors

[edit]Rulers' need for taxation

[edit]Robert Bates and Donald Lien, as well as David Stasavage, have argued that rulers' need for taxes gave asset-owning elites the bargaining power to demand a say on public policy, thus giving rise to democratic institutions.[101][102][103] Montesquieu argued that the mobility of commerce meant that rulers had to bargain with merchants in order to tax them, otherwise they would leave the country or hide their commercial activities.[104][101] Stasavage argues that the small size and backwardness of European states, as well as the weakness of European rulers, after the fall of the Roman Empire meant that European rulers had to obtain consent from their population to govern effectively.[103][102]

According to Clark, Golder, and Golder, an application of Albert O. Hirschman's exit, voice, and loyalty model is that if individuals have plausible exit options, then a government may be more likely to democratize. James C. Scott argues that governments may find it difficult to claim a sovereignty over a population when that population is in motion.[105] Scott additionally asserts that exit may not solely include physical exit from the territory of a coercive state, but can include a number of adaptive responses to coercion that make it more difficult for states to claim sovereignty over a population. These responses can include planting crops that are more difficult for states to count, or tending livestock that are more mobile. In fact, the entire political arrangement of a state is a result of individuals adapting to the environment, and making a choice as to whether or not to stay in a territory.[105] If people are free to move, then the exit, voice, and loyalty model predicts that a state will have to be of that population representative, and appease the populace in order to prevent them from leaving.[106] If individuals have plausible exit options then they are better able to constrain a government's arbitrary behaviour through threat of exit.[106]

Inequality and democracy

[edit]Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson argued that the relationship between social equality and democratic transition is complicated: People have less incentive to revolt in an egalitarian society (for example, Singapore), so the likelihood of democratization is lower. In a highly unequal society (for example, South Africa under Apartheid), the redistribution of wealth and power in a democracy would be so harmful to elites that these would do everything to prevent democratization. Democratization is more likely to emerge somewhere in the middle, in the countries, whose elites offer concessions because (1) they consider the threat of a revolution credible and (2) the cost of the concessions is not too high.[107] This expectation is in line with the empirical research showing that democracy is more stable in egalitarian societies.[69]

Other approaches to the relationship between inequality and democracy have been presented by Carles Boix, Stephan Haggard Robert Kaufman,Ben Ansell, and David Samuels.[108][109]

In their 2019 book The Narrow Corridor and a 2022 study in the American Political Science Review, Acemoglu and Robinson argue that the nature of the relationship between elites and society determine whether stable democracy emerges. When elites are overly dominant, despotic states emerge. When society is overly dominant, weak states emerge. When elites and society are evenly balance, inclusive states emerge.[110][111]

Natural resources

[edit]

Research shows that oil wealth lowers levels of democracy and strengthens autocratic rule.[112][113][114][115][116][117][118][119][120][121] According to Michael Ross, petroleum is the sole resource that has "been consistently correlated with less democracy and worse institutions" and is the "key variable in the vast majority of the studies" identifying some type of resource curse effect.[122] A 2014 meta-analysis confirms the negative impact of oil wealth on democratization.[123]

Thad Dunning proposes a plausible explanation for Ecuador's return to democracy that contradicts the conventional wisdom that natural resource rents encourage authoritarian governments. Dunning proposes that there are situations where natural resource rents, such as those acquired through oil, reduce the risk of distributive or social policies to the elite because the state has other sources of revenue to finance this kind of policies that is not the elite wealth or income.[124] And in countries plagued with high inequality, which was the case of Ecuador in the 1970s, the result would be a higher likelihood of democratization.[125] In 1972, the military coup had overthrown the government in large part because of the fears of elites that redistribution would take place.[126] That same year oil became an increasing financial source for the country.[126] Although the rents were used to finance the military, the eventual second oil boom of 1979 ran parallel to the country's re-democratization.[126] Ecuador's re-democratization can then be attributed, as argued by Dunning, to the large increase of oil rents, which enabled not only a surge in public spending but placated the fears of redistribution that had grappled the elite circles.[126] The exploitation of Ecuador's resource rent enabled the government to implement price and wage policies that benefited citizens at no cost to the elite and allowed for a smooth transition and growth of democratic institutions.[126]

The thesis that oil and other natural resources have a negative impact on democracy has been challenged by historian Stephen Haber and political scientist Victor Menaldo in a widely cited article in the American Political Science Review (2011). Haber and Menaldo argue that "natural resource reliance is not an exogenous variable" and find that when tests of the relationship between natural resources and democracy take this point into account "increases in resource reliance are not associated with authoritarianism."[127]

Cultural factors

[edit]Values and religion

[edit]It is claimed by some that certain cultures are simply more conducive to democratic values than others. This view is likely to be ethnocentric. Typically, it is Western culture which is cited as "best suited" to democracy, with other cultures portrayed as containing values which make democracy difficult or undesirable. This argument is sometimes used by undemocratic regimes to justify their failure to implement democratic reforms. Today, however, there are many non-Western democracies. Examples include India, Japan, Indonesia, Namibia, Botswana, Taiwan, and South Korea. Research finds that "Western-educated leaders significantly and substantively improve a country's democratization prospects".[128]

Huntington presented an influential, but also controversial arguments about Confucianism and Islam. Huntington held that "In practice Confucian or Confucian-influenced societies have been inhospitable to democracy."[129] He also held that "Islamic doctrine ... contains elements that may be both congenial and uncongenial to democracy," but generally thought that Islam was an obstacle to democratization.[130] In contrast, Alfred Stepan was more optimistic about the compatibility of different religions and democracy.[131]

Steven Fish and Robert Barro have linked Islam to undemocratic outcomes.[132][133] However, Michael Ross argues that the lack of democracies in some parts of the Muslim world has more to do with the adverse effects of the resource curse than Islam.[134] Lisa Blaydes and Eric Chaney have linked the democratic divergence between the West and the Middle-East to the reliance on mamluks (slave soldiers) by Muslim rulers whereas European rulers had to rely on local elites for military forces, thus giving those elites bargaining power to push for representative government.[135]

Robert Dahl argued, in On Democracy, that countries with a "democratic political culture" were more prone for democratization and democratic survival.[68] He also argued that cultural homogeneity and smallness contribute to democratic survival.[68][136] Other scholars have however challenged the notion that small states and homogeneity strengthen democracy.[137]

A 2012 study found that areas in Africa with Protestant missionaries were more likely to become stable democracies.[138] A 2020 study failed to replicate those findings.[139]

Sirianne Dahlum and Carl Henrik Knutsen offer a test of the Ronald Inglehart and Christian Welzel revised version of modernization theory, which focuses on cultural traits triggered by economic development that are presumed to be conducive to democratization.[140] They find "no empirical support" for the Inglehart and Welzel thesis and conclude that "self-expression values do not enhance democracy levels or democratization chances, and neither do they stabilize existing democracies."[141]

Education

[edit]It has long been theorized that education promotes stable and democratic societies.[142] Research shows that education leads to greater political tolerance, increases the likelihood of political participation and reduces inequality.[143] One study finds "that increases in levels of education improve levels of democracy and that the democratizing effect of education is more intense in poor countries".[143]

It is commonly claimed that democracy and democratization were important drivers of the expansion of primary education around the world. However, new evidence from historical education trends challenges this assertion. An analysis of historical student enrollment rates for 109 countries from 1820 to 2010 finds no support for the claim that democratization increased access to primary education around the world. It is true that transitions to democracy often coincided with an acceleration in the expansion of primary education, but the same acceleration was observed in countries that remained non-democratic.[144]

Wider adoption of voting advice applications can lead to increased education on politics and increased voter turnout.[145]

Social capital and civil society

[edit]

Civil society refers to a collection of non-governmental organizations and institutions that advance the interests, priorities and will of citizens. Social capital refers to features of social life—networks, norms, and trust—that allow individuals to act together to pursue shared objectives.[8]

Robert Putnam argues that certain characteristics make societies more likely to have cultures of civic engagement that lead to more participatory democracies. According to Putnam, communities with denser horizontal networks of civic association are able to better build the "norms of trust, reciprocity, and civic engagement" that lead to democratization and well-functioning participatory democracies. By contrasting communities in Northern Italy, which had dense horizontal networks, to communities in Southern Italy, which had more vertical networks and patron-client relations, Putnam asserts that the latter never built the culture of civic engagement that some deem as necessary for successful democratization.[146]

Sheri Berman has rebutted Putnam's theory that civil society contributes to democratization, writing that in the case of the Weimar Republic, civil society facilitated the rise of the Nazi Party.[147] According to Berman, Germany's democratization after World War I allowed for a renewed development in the country's civil society; however, Berman argues that this vibrant civil society eventually weakened democracy within Germany as it exacerbated existing social divisions due to the creation of exclusionary community organizations.[147] Subsequent empirical research and theoretical analysis has lent support for Berman's argument.[148] Yale University political scientist Daniel Mattingly argues civil society in China helps the authoritarian regime in China to cement control.[149] Clark, M. Golder, and S. Golder also argue that despite many believing democratization requires a civic culture, empirical evidence produced by several reanalyses of past studies suggest this claim is only partially supported.[14] Philippe C. Schmitter also asserts that the existence of civil society is not a prerequisite for the transition to democracy, but rather democratization is usually followed by the resurrection of civil society (even if it did not exist previously).[16]

Research indicates that democracy protests are associated with democratization. According to a study by Freedom House, in 67 countries where dictatorships have fallen since 1972, nonviolent civic resistance was a strong influence over 70 percent of the time. In these transitions, changes were catalyzed not through foreign invasion, and only rarely through armed revolt or voluntary elite-driven reforms, but overwhelmingly by democratic civil society organizations utilizing nonviolent action and other forms of civil resistance, such as strikes, boycotts, civil disobedience, and mass protests.[150] A 2016 study found that about a quarter of all cases of democracy protests between 1989 and 2011 lead to democratization.[151]

Theories based on political agents and choices

[edit]Elite-opposition negotiations and contingency

[edit]Scholars such as Dankwart A. Rustow,[152][153] Guillermo O'Donnell and Philippe C. Schmitter in their classic Transitions from Authoritarian Rule: Tentative Conclusions about Uncertain Democracies (1986),[154] argued against the notion that there are structural "big" causes of democratization. These scholars instead emphasize how the democratization process occurs in a more contingent manner that depends on the characteristics and circumstances of the elites who ultimately oversee the shift from authoritarianism to democracy.

O'Donnell and Schmitter proposed a strategic choice approach to transitions to democracy that highlighted how they were driven by the decisions of different actors in response to a core set of dilemmas. The analysis centered on the interaction among four actors: the hard-liners and soft-liners who belonged to the incumbent authoritarian regime, and the moderate and radical oppositions against the regime. This book not only became the point of reference for a burgeoning academic literature on democratic transitions, it was also read widely by political activists engaged in actual struggles to achieve democracy.[155]

Adam Przeworski, in Democracy and the Market (1991), offered the first analysis of the interaction between rulers and opposition in transitions to democracy using rudimentary game theory. and he emphasizes the interdependence of political and economic transformations.[156]

Elite-driven democratization

[edit]Scholars have argued that processes of democratization may be elite-driven or driven by the authoritarian incumbents as a way for those elites to retain power amid popular demands for representative government.[157][158][159][160] If the costs of repression are higher than the costs of giving away power, authoritarians may opt for democratization and inclusive institutions.[161][162][163] According to a 2020 study, authoritarian-led democratization is more likely to lead to lasting democracy in cases when the party strength of the authoritarian incumbent is high.[164] However, Michael Albertus and Victor Menaldo argue that democratizing rules implemented by outgoing authoritarians may distort democracy in favor of the outgoing authoritarian regime and its supporters, resulting in "bad" institutions that are hard to get rid of.[165] According to Michael K. Miller, elite-driven democratization is particularly likely in the wake of major violent shocks (either domestic or international) which provide openings to opposition actors to the authoritarian regime.[163] Dan Slater and Joseph Wong argue that dictators in Asia chose to implement democratic reforms when they were in positions of strength in order to retain and revitalize their power.[160]

According to a study by political scientist Daniel Treisman, influential theories of democratization posit that autocrats "deliberately choose to share or surrender power. They do so to prevent revolution, motivate citizens to fight wars, incentivize governments to provide public goods, outbid elite rivals, or limit factional violence." His study shows that in many cases, "democratization occurred not because incumbent elites chose it but because, in trying to prevent it, they made mistakes that weakened their hold on power. Common mistakes include: calling elections or starting military conflicts, only to lose them; ignoring popular unrest and being overthrown; initiating limited reforms that get out of hand; and selecting a covert democrat as leader. These mistakes reflect well-known cognitive biases such as overconfidence and the illusion of control."[166]

Sharun Mukand and Dani Rodrik dispute that elite-driven democratization produce liberal democracy. They argue that low levels of inequality and weak identity cleavages are necessary for liberal democracy to emerge.[167] A 2020 study by several political scientists from German universities found that democratization through bottom-up peaceful protests led to higher levels of democracy and democratic stability than democratization prompted by elites.[168]

The three dictatorship types, monarchy, civilian and military have different approaches to democratization as a result of their individual goals. Monarchic and civilian dictatorships seek to remain in power indefinitely through hereditary rule in the case of monarchs or through oppression in the case of civilian dictators. A military dictatorship seizes power to act as a caretaker government to replace what they consider a flawed civilian government. Military dictatorships are more likely to transition to democracy because at the onset, they are meant to be stop-gap solutions while a new acceptable government forms.[169][170][171]

Research suggests that the threat of civil conflict encourages regimes to make democratic concessions. A 2016 study found that drought-induced riots in Sub-Saharan Africa lead regimes, fearing conflict, to make democratic concessions.[172]

Scrambled constituencies

[edit]Mancur Olson theorizes that the process of democratization occurs when elites are unable to reconstitute an autocracy. Olson suggests that this occurs when constituencies or identity groups are mixed within a geographic region. He asserts that this mixed geographic constituencies requires elites to for democratic and representative institutions to control the region, and to limit the power of competing elite groups.[173]

Death or ouster of dictator

[edit]One analysis found that "Compared with other forms of leadership turnover in autocracies—such as coups, elections, or term limits—which lead to regime collapse about half of the time, the death of a dictator is remarkably inconsequential. ... of the 79 dictators who have died in office (1946–2014)... in the vast majority (92%) of cases, the regime persists after the autocrat's death."[174]

Women's suffrage

[edit]One of the critiques of Huntington's periodization is that it doesn't give enough weight to universal suffrage.[175][176] Pamela Paxton argues that once women's suffrage is taken into account, the data reveal "a long, continuous democratization period from 1893–1958, with only war-related reversals."[177]

International factors

[edit]War and national security

[edit]Jeffrey Herbst, in his paper "War and the State in Africa" (1990), explains how democratization in European states was achieved through political development fostered by war-making and these "lessons from the case of Europe show that war is an important cause of state formation that is missing in Africa today."[178] Herbst writes that war and the threat of invasion by neighbors caused European state to more efficiently collect revenue, forced leaders to improve administrative capabilities, and fostered state unification and a sense of national identity (a common, powerful association between the state and its citizens).[178] Herbst writes that in Africa and elsewhere in the non-European world "states are developing in a fundamentally new environment" because they mostly "gained Independence without having to resort to combat and have not faced a security threat since independence."[178] Herbst notes that the strongest non-European states, South Korea and Taiwan, are "largely 'warfare' states that have been molded, in part, by the near constant threat of external aggression."[178]

Elizabeth Kier has challenged claims that total war prompts democratization, showing in the cases of the UK and Italy during World War I that the policies adopted by the Italian government prompted a fascist backlash whereas UK government policies towards labor undermined broader democratization.[179]

War and peace

[edit]

Wars may contribute to the state-building that precedes a transition to democracy, but war is mainly a serious obstacle to democratization. While adherents of the democratic peace theory believe that democracy causes peace, the territorial peace theory makes the opposite claim that peace causes democracy. In fact, war and territorial threats to a country are likely to increase authoritarianism and lead to autocracy. This is supported by historical evidence showing that in almost all cases, peace has come before democracy. A number of scholars have argued that there is little support for the hypothesis that democracy causes peace, but strong evidence for the opposite hypothesis that peace leads to democracy.[180][181][182]

Christian Welzel's human empowerment theory posits that existential security leads to emancipative cultural values and support for a democratic political organization.[183] This is in agreement with theories based on evolutionary psychology. The so-called regality theory finds that people develop a psychological preference for a strong leader and an authoritarian form of government in situations of war or perceived collective danger. On the other hand, people will support egalitarian values and a preference for democracy in situations of peace and safety. The consequence of this is that a society will develop in the direction of autocracy and an authoritarian government when people perceive collective danger, while the development in the democratic direction requires collective safety.[184]

International institutions

[edit]A number of studies have found that international institutions have helped facilitate democratization.[185][186][187] Thomas Risse wrote in 2009, "there is a consensus in the literature on Eastern Europe that the EU membership perspective had a huge anchoring effects for the new democracies."[188] Scholars have also linked NATO expansion with playing a role in democratization.[189] international forces can significantly affect democratization. Global forces like the diffusion of democratic ideas and pressure from international financial institutions to democratize have led to democratization.[190]

Promotion, foreign influence, and intervention

[edit]The European Union has contributed to the spread of democracy, in particular by encouraging democratic reforms in aspiring member states. Thomas Risse wrote in 2009, "there is a consensus in the literature on Eastern Europe that the EU membership perspective had a huge anchoring effects for the new democracies."[188]

Steven Levitsky and Lucan Way have argued that close ties to the West increased the likelihood of democratization after the end of the Cold War, whereas states with weak ties to the West adopted competitive authoritarian regimes.[191][192]

A 2002 study found that membership in regional organizations "is correlated with transitions to democracy during the period from 1950 to 1992."[193]

A 2004 study found no evidence that foreign aid led to democratization.[194]

Democracies have often been imposed by military intervention, for example in Japan and Germany after World War II.[195][196] In other cases, decolonization sometimes facilitated the establishment of democracies that were soon replaced by authoritarian regimes. For example, Syria, after gaining independence from French mandatory control at the beginning of the Cold War, failed to consolidate its democracy, so it eventually collapsed and was replaced by a Ba'athist dictatorship.[197]

Robert Dahl argued in On Democracy that foreign interventions contributed to democratic failures, citing Soviet interventions in Central and Eastern Europe and U.S. interventions in Latin America.[68] However, the delegitimization of empires contributed to the emergence of democracy as former colonies gained independence and implemented democracy.[68]

Geographic factors

[edit]Some scholars link the emergence and sustenance of democracies to areas with access to the sea, which tends to increase the mobility of people, goods, capital, and ideas.[198][199]

Historical factors

[edit]Historical legacies

[edit]In seeking to explain why North America developed stable democracies and Latin America did not, Seymour Martin Lipset, in The Democratic Century (2004), holds that the reason is that the initial patterns of colonization, the subsequent process of economic incorporation of the new colonies, and the wars of independence differ. The divergent histories of Britain and Iberia are seen as creating different cultural legacies that affected the prospects of democracy.[200] A related argument is presented by James A. Robinson in "Critical Junctures and Developmental Paths" (2022).[201]

Sequencing and causality

[edit]Scholars have discussed whether the order in which things happen helps or hinders the process of democratization. An early discussion occurred in the 1960s and 1970s. Dankwart Rustow argued that "'the most effective sequence' is the pursuit of national unity, government authority, and political equality, in that order."[202] Eric Nordlinger and Samuel Huntington stressed "the importance of developing effective governmental institutions before the emergence of mass participation in politics."[202] Robert Dahl, in Polyarchy: Participation and Opposition (1971), held that the "commonest sequence among the older and more stable polyarchies has been some approximation of the ... path [in which] competitive politics preceded expansion in participation."[203]

In the 2010s, the discussion focused on the impact of the sequencing between state building and democratization. Francis Fukuyama, in Political Order and Political Decay (2014), echoes Huntington's "state-first" argument and holds that those "countries in which democracy preceded modern state-building have had much greater problems achieving high-quality governance."[204] This view has been supported by Sheri Berman, who offers a sweeping overview of European history and concludes that "sequencing matters" and that "without strong states...liberal democracy is difficult if not impossible to achieve." [205]

However, this state-first thesis has been challenged. Relying on a comparison of Denmark and Greece, and quantitative research on 180 countries across 1789–2019, Haakon Gjerløw, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Tore Wig, and Matthew C. Wilson, in One Road to Riches? (2022), "find little evidence to support the stateness-first argument."[206] Based on a comparison of European and Latin American countries, Sebastián Mazzuca and Gerardo Munck, in A Middle-Quality Institutional Trap (2021), argue that counter to the state-first thesis, the "starting point of political developments is less important than whether the State–democracy relationship is a virtuous cycle, triggering causal mechanisms that reinforce each."[207]

In sequences of democratization for many countries, Morrison et al. found elections as the most frequent first element of the sequence of democratization but found this ordering does not necessarily predict successful democratization.[208]

The democratic peace theory claims that democracy causes peace, while the territorial peace theory claims that peace causes democracy.[209]

Notes

[edit]- ^ In 1848, Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour had formed a parliamentary group in the Kingdom of Sardinia Parliament named the Partito Liberale Italiano (Italian Liberal Party). From 1860, with the Unification of Italy substantially realized and the death of Cavour himself in 1861, the Liberal Party was split into at least two major factions or new parties later known as the Destra Storica on the right-wing, who substantially assembled the Count of Cavour's followers and political heirs; and the Sinistra Storica on the left-wing, who mostly reunited the followers and sympathizers of Giuseppe Garibaldi and other former Mazzinians. The Historical Right (Destra Storica) and the Historical Left (Sinistra Storica) were composed of royalist liberals. At the same time, radicals organized themselves into the Radical Party and republicans into the Italian Republican Party.

- ^ Some historians suggest an earlier date for the conclusion of the Transition[47] including the 1977 general election, the 1978 Constitution, or the 1981 attempted coup. One writer suggests the Transition only concluded in 2006 with the end of consensus politics and the re-emergence of open debate on divisive issues.[48]

References

[edit]- ^ Arugay, Aries A. (2021). "Democratic Transitions". The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Global Security Studies. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 1–7. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-74336-3_190-1. ISBN 978-3-319-74336-3. S2CID 240235199.

- ^ Lindenfors, Patrik; Wilson, Matthew; Lindberg, Staffan I. (2020). "The Matthew effect in political science: head start and key reforms important for democratization". Humanities and Social Sciences Communications. 7 (106) 106. doi:10.1057/s41599-020-00596-7.

- ^ Schmitz, Hans Peter (2004). "Domestic and Transnational Perspectives on Democratization". International Studies Review. 6 (3). [International Studies Association, Wiley]: 403–426. doi:10.1111/j.1521-9488.2004.00423.x. ISSN 1521-9488. JSTOR 3699697.

- ^ Bogaards, Matthijs (2010). "Measures of Democratization: From Degree to Type to War". Political Research Quarterly. 63 (2). [University of Utah, Sage Publications, Inc.]: 475–488. doi:10.1177/1065912909358578. ISSN 1065-9129. JSTOR 20721505. S2CID 154168435.

- ^ "Global Dashboard". BTI 2022. Retrieved Apr 17, 2023.

- ^ Huntington, Samuel P. (1991). Democratization in the Late 20th century. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

- ^ Renske Doorenspleet, "Reassessing the Three Waves of Democratization." World Politics 52(3) 2000: 384–406.

- ^ a b John Markoff, Waves of Democracy: Social Movements and Political Change, Second Edition. New York: Routledge, 2015.

- ^ a b Gunitsky, Seva (2018). "Democratic Waves in Historical Perspective" (PDF). Perspectives on Politics. 16 (3): 634–651. doi:10.1017/S1537592718001044. ISSN 1537-5927. S2CID 149523316. Archived (PDF) from the original on Dec 26, 2022.

- ^ Skaaning, Svend-Erik (2020). "Waves of autocratization and democratization: A critical note on conceptualization and measurement". Democratization. 27 (8): 1533–1542. doi:10.1080/13510347.2020.1799194. S2CID 225378571.

- ^ Democracy Report 2024, Varieties of Democracy

- ^ Miller, Michael K. (2021). "Ch. 2". Shock to the system: coups, elections, and war on the road to democratization. Princeton Oxford: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-21701-7.

- ^ Miller, Michael K. (April 2021). "Don't Call It a Comeback: Autocratic Ruling Parties After Democratization". British Journal of Political Science. 51 (2): 559–583. doi:10.1017/S0007123419000012. ISSN 0007-1234. S2CID 203150075.

- ^ a b Berman, Sherri (January 2007). "How Democracy Works: Lessons from Europe" (PDF). Journal of Democracy. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-11. Retrieved 2008-04-17.

- ^ Hegre, Håvard (May 15, 2014). "Democratization and Political Violence". ourworld.unu.edu. Retrieved 2021-02-14.

- ^ a b Andersen, David (2021). "Democratization and Violent Conflict: Is There A Scandinavian Exception?". Scandinavian Political Studies. 44 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1111/1467-9477.12178. ISSN 1467-9477. S2CID 225624391.

- ^ Ober, Josiah (1996). The Athenian Revolution. Princeton University Press. pp. 32–52.

- ^ "Anti-Government Protesters Confront Benin's Riot Police". NewYorkTimes. December 14, 1989.

- ^ Tosta, Antonio Luciano de Andrade; Coutinho, Eduardo F. (2015). Brazil. ABC-CLIO. p. 353. ISBN 978-1-61069-258-8.

- ^ Orme 1988, pp. 247–248.

- ^ a b Scott, Sam (2001). "Transition to democracy in Chile | two factors". ScholarWorks: 12.

- ^ "Chile: Period of democratic transition: 1988–1989, Pro-democracy civic movement: present" (PDF). Freedomhouse.

- ^ Clark, William; Golder, Matt; Golder, Sona. Foundations of Comparative Politics. p. Chapter 7.

- ^ Plaistad, Shandra. "Chileans overthrow Pinochet regime, 1983–1988". Global Nonviolent Action Database.

- ^ Geddes, Barbra (1999). "What Do We Know About Democratization After Twenty Years?". Annual Review of Political Science. 2: 7. doi:10.1146/annurev.polisci.2.1.115.

- ^ a b Stefan Berger, "The Attempt at Democratization under Weimar" in European Democratization since 1800. Eds. John Garrard, Vera Tolz & Ralph White (Springer, 2000), pp. 96–115.

- ^ Richard L. Merritt, Democracy Imposed: U.S. Occupation Policy and the German Public, 1945–1949 (Yale University Press, 1995).

- ^ "From legal document to public myth: Magna Carta in the 17th century". The British Library. Archived from the original on 2017-10-18. Retrieved 2017-10-16; "Magna Carta: Magna Carta in the 17th Century". The Society of Antiquaries of London. Archived from the original on 2018-09-25. Retrieved 2017-10-16.

- ^ "Origins and growth of Parliament". The National Archives. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- ^ "Putney debates". The British Library. Archived from the original on 22 December 2016. Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- ^ "Britain's unwritten constitution". British Library. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

The key landmark is the Bill of Rights (1689), which established the supremacy of Parliament over the Crown.... The Bill of Rights (1689) then settled the primacy of Parliament over the monarch's prerogatives, providing for the regular meeting of Parliament, free elections to the Commons, free speech in parliamentary debates, and some basic human rights, most famously freedom from 'cruel or unusual punishment'.

- ^ "Constitutionalism: America & Beyond". Bureau of International Information Programs (IIP), U.S. Department of State. Archived from the original on 24 October 2014. Retrieved 30 October 2014.

The earliest, and perhaps greatest, victory for liberalism was achieved in England. The rising commercial class that had supported the Tudor monarchy in the 16th century led the revolutionary battle in the 17th, and succeeded in establishing the supremacy of Parliament and, eventually, of the House of Commons. What emerged as the distinctive feature of modern constitutionalism was not the insistence on the idea that the king is subject to law (although this concept is an essential attribute of all constitutionalism). This notion was already well established in the Middle Ages. What was distinctive was the establishment of effective means of political control whereby the rule of law might be enforced. Modern constitutionalism was born with the political requirement that representative government depended upon the consent of citizen subjects.... However, as can be seen through provisions in the 1689 Bill of Rights, the English Revolution was fought not just to protect the rights of property (in the narrow sense) but to establish those liberties which liberals believed essential to human dignity and moral worth. The "rights of man" enumerated in the English Bill of Rights gradually were proclaimed beyond the boundaries of England, notably in the American Declaration of Independence of 1776 and in the French Declaration of the Rights of Man in 1789.

- ^ "Rise of Parliament". The National Archives. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ^ "AUTONOMISMO E UNITÀ" (in Italian). Retrieved 16 September 2023.

- ^ Mack Smith, Denis (1997). Modern Italy: A Political History. Yale University Press.

- ^ "Italia", Dizionario enciclopedico italiano (in Italian), vol. VI, Treccani, 1970, p. 456

- ^ Damage Foreshadows A-Bomb Test, 1946/06/06 (1946). Universal Newsreel. 1946. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ Smyth, Howard McGaw Italy: From Fascism to the Republic (1943–1946) The Western Political Quarterly vol. 1 no. 3 (pp. 205–222), September 1948.JSTOR 442274

- ^ a b c d Kent E. Calder, "East Asian Democratic Transitions" in The Making and Unmaking of Democracy: Lessons from History and World Politics (eds. Theodore K. Rabb & Ezra N. Suleiman: Routledge, 2003). pp. 251–59.

- ^ "Analysis: Madagascar's massive protests". BBC News. February 5, 2002.

- ^ "Malawi Electoral Laws" (PDF). MEC. Retrieved 18 February 2025.

- ^ Adam Przeworski and Henry Teune, Democracy and the Limits of Self-Government. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010, p. 47.

- ^ Adam Przeworski and Henry Teune, Democracy and the Limits of Self-Government. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010, p. 2; Przeworski, Adam, "The Mechanics of Regime Instability in Latin America." Journal of Politics in Latin America 1(1) 2009: 5–36.

- ^ Collier, Ruth Berins, and David Collier. Shaping the Political Arena: Critical Junctures, the Labor Movement, and Regime Dynamics in Latin America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1991; Rueschemeyer, Dietrich, Evelyne Huber Stephens, and John D. Stephens, Capitalist Development and Democracy. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1992; Collier, Ruth Berins, Paths Toward Democracy: The Working Class and Elites in Western Europe and South America. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 1999; Drake, Paul W.. Between Tyranny and Anarchy: A History of Democracy in Latin America, 1800–2006. Redwood City: Stanford University Press, 2009.

- ^ Colomer Rubio 2012, p. 260.

- ^ a b c Casanova & Gil Andrés 2014, p. 291.

- ^ Ortuño Anaya 2005, p. 22.

- ^ Tremlett 2008, p. 379.

- ^ Olmstead, Larry (1993-07-05). "Mandela and de Klerk Receive Liberty Medal in Philadelphia". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-07-23.

- ^ Katsiaficas 2012, p. 277.

- ^

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Country Studies. Federal Research Division. - Russia, section Demokratizatsiya. Data as of July 1996 (retrieved December 25, 2014)

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Country Studies. Federal Research Division. - Russia, section Demokratizatsiya. Data as of July 1996 (retrieved December 25, 2014)

- ^ "Tunisia Dossier: The Tunisian Revolution of Dignity". Archived from the original on 14 April 2023. Retrieved 14 April 2023.

- ^ Aleya-Sghaier, Amira (2012). "The Tunisian Revolution: The Revolution of Dignity". The Journal of the Middle East and Africa. 3: 18–45. doi:10.1080/21520844.2012.675545. S2CID 144602886. Archived from the original on 14 April 2023. Retrieved 14 April 2023.

- ^ "Enough with the 'Jasmine Revolution' narrative: Tunisians demand dignity". Archived from the original on 14 April 2023. Retrieved 14 April 2023.

Let's say no to "jasmine" and stick to the name that was enshrined in our new constitution - the Tunisian Revolution of Dignity -to remind ourselves where our common efforts must remain focused.

- ^ Wolf, Anne (2023). Ben Ali's Tunisia: Power and Contention in an Authoritarian Regime. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-286850-3.

- ^ Ryan, Yasmine (26 January 2011). "How Tunisia's revolution began – Features". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 3 February 2011. Retrieved 13 February 2011.

- ^ Sappa, M. M. "Національно-визвольна революція в Україні 1989–1991 рр. як продукт соціального руху з багатовекторною мережною структурою" [The 1989–1991 National Liberation Revolution in Ukraine as a product of a social movement and multivector network of structures]. Kharkiv National University of Internal Affairs. Retrieved 17 December 2023.

- ^ Wood, The Radicalism of the American Revolution (1992)

- ^ Greene and Pole (1994) chapter 70

- ^ "Expansion of Rights and Liberties – The Right of Suffrage". Online Exhibit: The Charters of Freedom. National Archives. Archived from the original on July 6, 2016. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- ^ Gerring, John; Knutsen, Carl Henrik; Berge, Jonas (2022). "Does Democracy Matter?". Annual Review of Political Science. 25: 357–375. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-060820-060910. hdl:10852/100947.

- ^ Lipset, Seymour Martin (1959). "Some Social Requisites of Democracy: Economic Development and Political Legitimacy". The American Political Science Review. 53 (1): 69–105. doi:10.2307/1951731. ISSN 0003-0554. JSTOR 1951731. S2CID 53686238.

- ^ Boix, Carles; Stokes, Susan C. (2003). "Endogenous Democratization". World Politics. 55 (4): 517–549. doi:10.1353/wp.2003.0019. ISSN 0043-8871. S2CID 18745191.

- ^ Capitalist Development and Democracy. University Of Chicago Press. 1992.

- ^ Geddes, Barbara (2011). Goodin, Robert E (ed.). "What Causes Democratization". The Oxford Handbook of Political Science. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199604456.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-960445-6. Archived from the original on 2014-05-30.

- ^ Korom, Philipp (2019). "The political sociologist Seymour M. Lipset: Remembered in political science, neglected in sociology". European Journal of Cultural and Political Sociology. 6 (4): 448–473. doi:10.1080/23254823.2019.1570859. ISSN 2325-4823. PMC 7099882. PMID 32309461.

- ^ Treisman, Daniel (2020). "Economic Development and Democracy: Predispositions and Triggers". Annual Review of Political Science. 23: 241–257. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-050718-043546. ISSN 1094-2939.

- ^ a b c d e f Dahl, Robert. "On Democracy". yalebooks.yale.edu. Yale University Press. Retrieved 2020-02-02.

- ^ a b c Przeworski, Adam; et al. (2000). Democracy and Development: Political Institutions and Well-Being in the World, 1950–1990. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Rice, Tom W.; Ling, Jeffrey (2002-12-01). "Democracy, Economic Wealth and Social Capital: Sorting Out the Causal Connections". Space and Polity. 6 (3): 307–325. doi:10.1080/1356257022000031995. ISSN 1356-2576. S2CID 144947268.

- ^ Treisman, Daniel (2015-10-01). "Income, Democracy, and Leader Turnover". American Journal of Political Science. 59 (4): 927–942. doi:10.1111/ajps.12135. ISSN 1540-5907. S2CID 154067095.

- ^ Traversa, Federico (2014). "Income and the stability of democracy: Pushing beyond the borders of logic to explain a strong correlation?". Constitutional Political Economy. 26 (2): 121–136. doi:10.1007/s10602-014-9175-x. S2CID 154420163.

- ^ FENG, YI (July 1997). "Democracy, Political Stability and Economic Growth". British Journal of Political Science. 27 (3): 416, 391–418. doi:10.1017/S0007123497000197. S2CID 154749945.

- ^ Clark, William Roberts; Golder, Matt; Golder, Sona N. (2013). "Power and politics: insights from an exit, voice, and loyalty game" (PDF). Unpublished Manuscript.

- ^ "Origins and growth of Parliament". The National Archives. Retrieved 7 April 2015."Origins and growth of Parliament". The National Archives. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- ^ Przeworski, Adam; Limongi, Fernando (1997). "Modernization: Theories and Facts". World Politics. 49 (2): 155–183. doi:10.1353/wp.1997.0004. ISSN 0043-8871. JSTOR 25053996. S2CID 5981579.

- ^ Magaloni, Beatriz (September 2006). Voting for Autocracy: Hegemonic Party Survival and its Demise in Mexico. Cambridge Core. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511510274. ISBN 978-0-521-86247-9. Retrieved 2019-12-17.

- ^ "The Puzzle of the Chinese Middle Class". Journal of Democracy. Retrieved 2019-12-22.

- ^ Miller, Michael K. (2012). "Economic Development, Violent Leader Removal, and Democratization". American Journal of Political Science. 56 (4): 1002–1020. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5907.2012.00595.x.

- ^ Glaeser, Edward L.; Steinberg, Bryce Millett (2017). "Transforming Cities: Does Urbanization Promote Democratic Change?" (PDF). Regional Studies. 51 (1): 58–68. Bibcode:2017RegSt..51...58G. doi:10.1080/00343404.2016.1262020. S2CID 157638952.

- ^ Barceló, Joan; Rosas, Guillermo (2020). "Endogenous democracy: causal evidence from the potato productivity shock in the old world". Political Science Research and Methods. 9 (3): 650–657. doi:10.1017/psrm.2019.62. ISSN 2049-8470.

- ^ "Aristotle: Politics | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy". www.iep.utm.edu. Retrieved 2020-02-03.

- ^ Rosenfeld, Bryn (2020). The Autocratic Middle Class: How State Dependency Reduces the Demand for Democracy. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-20977-7.

- ^ Acemoglu, Daron; Robinson, James (2022). "Non-Modernization: Power–Culture Trajectories and the Dynamics of Political Institutions". Annual Review of Political Science. 25: 323–339. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-051120-103913. hdl:1721.1/144425.

- ^ Gerardo L.Munck, "Modernization Theory as a Case of Failed Knowledge Production." The Annals of Comparative Democratization 16, 3 (2018): 37–41. [1] Archived 2019-08-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Van Noort, Sam (2024). "Industrialization and Democracy". World Politics. 76 (3): 457–498. doi:10.1353/wp.2024.a933069. ISSN 1086-3338.

- ^ FREEMAN, J. R., & QUINN, D. P. (2012). The Economic Origins of Democracy Reconsidered. American Political Science Review, 106(1), 58–80. doi:10.1017/S0003055411000505

- ^ Maxfield, S. (2000). Capital Mobility and Democratic Stability. Journal of Democracy 11(4), 95-106. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2000.0080.

- ^ Manger, Mark S.; Pickup, Mark A. (2016-02-01). "The Coevolution of Trade Agreement Networks and Democracy". Journal of Conflict Resolution. 60 (1): 164–191. doi:10.1177/0022002714535431. ISSN 0022-0027. S2CID 154493227.

- ^ Pronin, Pavel (2020). "International Trade And Democracy: How Trade Partners Affect Regime Change And Persistence" (PDF). SSRN Electronic Journal. Elsevier BV. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3717614. ISSN 1556-5068.

- ^ Chwieroth, J. M. (2010). Capital Ideas: The IMF and the Rise of Financial Liberalization. Princeton University Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt7sbnq

- ^ Moore, Barrington Jr. (1993) [1966]. Social origins of dictatorship and democracy: lord and peasant in the making of the modern world (with a new foreword by Edward Friedman and James C. Scott ed.). Boston: Beacon Press. p. 430. ISBN 978-0-8070-5073-6.

- ^ Jørgen Møller, State Formation, Regime Change, and Economic Development. London: Routledge Press, 2017, Ch. 6.

- ^ Dietrich Rueschemeyer, Evelyne Stephens, and John D. Stephens. 1992. Capitalist Development and Democracy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- ^ Bellin, Eva (January 2000). "Contingent Democrats: Industrialists, Labor, and Democratization in Late-Developing Countries". World Politics. 52 (2): 175–205. doi:10.1017/S0043887100002598. ISSN 1086-3338. S2CID 54044493.

- ^ J. Samuel Valenzuela, 2001. "Class Relations and Democratization: A Reassessment of Barrington Moore's Model", pp. 240–86, in Miguel Angel Centeno and Fernando López-Alves (eds.), The Other Mirror: Grand Theory Through the Lens of Latin America. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

- ^ James Mahoney, "Knowledge Accumulation in Comparative Historical Research: The Case of Democracy and Authoritarianism," pp. 131–74, in James Mahoney and Dietrich Rueschemeyer (eds.), Comparative Historical Analysis in the Social Sciences. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003, p. 145. For an earlier review of a wide range of critical response to Social Origins, see Jon Wiener, "Review of Reviews: Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy", History and Theory 15 (1976), 146–75.

- ^ Samuels, David J.; Thomson, Henry (2020). "Lord, Peasant … and Tractor? Agricultural Mechanization, Moore's Thesis, and the Emergence of Democracy". Perspectives on Politics. 19 (3): 739–753. doi:10.1017/S1537592720002303. ISSN 1537-5927. S2CID 225466533.

- ^ Stasavage, David (2003). Public Debt and the Birth of the Democratic State: France and Great Britain 1688–1789. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511510557. ISBN 978-0-521-80967-2. Retrieved 2019-12-24.

- ^ Negretto, Gabriel L.; Sánchez-Talanquer, Mariano (2021). "Constitutional Origins and Liberal Democracy: A Global Analysis, 1900–2015". American Political Science Review. 115 (2): 522–536. doi:10.1017/S0003055420001069. hdl:10016/39537. ISSN 0003-0554. S2CID 232422425.

- ^ a b Bates, Robert H.; Donald Lien, Da-Hsiang (March 1985). "A Note on Taxation, Development, and Representative Government" (PDF). Politics & Society. 14 (1): 53–70. doi:10.1177/003232928501400102. ISSN 0032-3292. S2CID 154910942.

- ^ a b Stasavage, David (2016-05-11). "Representation and Consent: Why They Arose in Europe and Not Elsewhere". Annual Review of Political Science. 19 (1): 145–162. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-043014-105648. ISSN 1094-2939.

- ^ a b Stasavage, David (2020). Decline and rise of democracy: a global history from antiquity to today. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-17746-5. OCLC 1125969950.

- ^ Deudney, Daniel H. (2010). Bounding Power: Republican Security Theory from the Polis to the Global Village. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-3727-4.

- ^ a b Scott, James C. (2010). The Art of not being governed: an anarchist history of upland Southeast Asia. NUS Press. pp. 7. ISBN 978-0-300-15228-9. OCLC 872296825.

- ^ a b "Power and politics: insights from an exit, voice, and loyalty game" (PDF).

- ^ Acemoglu, Daron; James A. Robinson (2006). Economic Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Special issue on "Inequality and Democratization: What Do We Know?"American Political Science Association. Comparative Democratization 11(3)2013.

- ^ Krauss, Alexander (January 2, 2016). "The scientific limits of understanding the (potential) relationship between complex social phenomena: the case of democracy and inequality". Journal of Economic Methodology. 23 (1): 97–109. doi:10.1080/1350178X.2015.1069372 – via Taylor and Francis+NEJM.

- ^ Acemoglu, Daron; Robinson, James A. (2022). "Weak, Despotic, or Inclusive? How State Type Emerges from State versus Civil Society Competition". American Political Science Review. 117 (2): 407–420. doi:10.1017/S0003055422000740. ISSN 0003-0554. S2CID 251607252.

- ^ Acemoglu, Daron; Robinson, James A. (2019). The Narrow Corridor: States, Societies, and the Fate of Liberty. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-241-31431-9.

- ^ Ross, Michael L. (13 June 2011). "Does Oil Hinder Democracy?". World Politics. 53 (3): 325–361. doi:10.1353/wp.2001.0011. S2CID 18404.

- ^ Wright, Joseph; Frantz, Erica; Geddes, Barbara (2015-04-01). "Oil and Autocratic Regime Survival". British Journal of Political Science. 45 (2): 287–306. doi:10.1017/S0007123413000252. ISSN 1469-2112. S2CID 988090.

- ^ Jensen, Nathan; Wantchekon, Leonard (2004-09-01). "Resource Wealth and Political Regimes in Africa" (PDF). Comparative Political Studies. 37 (7): 816–841. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.607.9710. doi:10.1177/0010414004266867. ISSN 0010-4140. S2CID 154999593.

- ^ Ulfelder, Jay (2007-08-01). "Natural-Resource Wealth and the Survival of Autocracy". Comparative Political Studies. 40 (8): 995–1018. doi:10.1177/0010414006287238. ISSN 0010-4140. S2CID 154316752.

- ^ Basedau, Matthias; Lay, Jann (2009-11-01). "Resource Curse or Rentier Peace? The Ambiguous Effects of Oil Wealth and Oil Dependence on Violent Conflict" (PDF). Journal of Peace Research. 46 (6): 757–776. doi:10.1177/0022343309340500. ISSN 0022-3433. S2CID 144798465.