Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

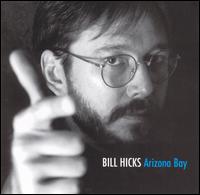

Arizona Bay

View on Wikipedia

| Arizona Bay | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Live album by | ||||

| Released | February 25, 1997 | |||

| Recorded | November 22, 1992 – June 1993 | |||

| Venue | Laff Stop, Austin, TX | |||

| Studio | Fossil Creek Studio, Austin, TX | |||

| Genre | Comedy | |||

| Length | 65:56 | |||

| Label | Rykodisc | |||

| Producer | Kevin Booth | |||

| Bill Hicks chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

Arizona Bay is an album by American stand-up comedian and satirist Bill Hicks, posthumously released in 1997. Both this album and a similar album of new material, Rant in E-Minor, were released posthumously by Rykodisc on February 25, 1997, marking three years since Hicks' death.[2]

The album's title refers to the hope that Los Angeles will one day fall into the ocean due to a major earthquake.[3] Hicks contends that the world will be better off in L.A.'s absence:

Ahhh, ha ha ha, it's gone, it's gone, it's gone. Oh, it's gone. All the shitty shows are gone, all the idiots screaming in the fucking wind are dead, I love it. Leaving nothing but a cool, beautiful serenity called...Arizona Bay. That's right, when L.A. falls in the fucking ocean and is flushed away, all that it will leave...is Arizona Bay.

On April 28, 2015, Comedy Dynamics released a new version of the album in the digital format called Arizona Bay Extended, featuring "a raw and uncut show that comprised the original Arizona Bay album."[4]

Musical content

[edit]Several of Hicks's albums are unique in that they feature background music, meant to enhance the album's mood. Such additions were made well after the initial recordings and are the product of Hicks's own musicianship.[5]

According to Kevin Booth, in the BBC documentary Dark Poet, it was during the early recording sessions for Arizona Bay, around Christmas 1992, that Hicks first started suffering from the pains in his side, which would later be diagnosed as pancreatic cancer. Upon learning that he had developed cancer, Hicks used his time to mix music into Rant in E-Minor and Arizona Bay, calling it his Dark Side of the Moon.[5]

Legacy

[edit]In 1996, one year prior to the release of Hicks' Arizona Bay album, American rock band Tool released the album Ænima, which contains several references to Hicks. The title song of the album echoes the theme of Los Angeles being submerged in the ocean and includes the lyrics, "Learn to swim, see you down in Arizona Bay." Additionally, there is artwork inside the album booklet showing a map of California before and after the earthquake, as well as a caricature of Hicks himself, cited as "another dead hero".

The song "Third Eye" also contains references to several Hicks routines:

- Who's that talking at the start of "Third Eye"? - That would be the aforementioned Bill Hicks; those are snips of comedy routines of his, from "The War on Drugs" (off his CD Dangerous) and "Drugs Have Done Good Things" (off Relentless). In fact, on his CD Rant in E-Minor, he refers to the power that heavy doses of hallucinogens have to "squeegee his third eye."[6]

Track listing

[edit]All music composed by Bill Hicks

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Goodbye You Lizard Scum" | 3:52 |

| 2. | "Step on the Gas (L.A. Riots)" | 4:50 |

| 3. | "Hooligans" | 4:20 |

| 4. | "Officer Nigger Hater" | 5:27 |

| 5. | "As Long as We're Talking Shelf Life (Kennedy)" | 5:00 |

| 6. | "The Elephant Is Dead (Bush)" | 1:57 |

| 7. | "Me & Saddam" | 3:10 |

| 8. | "Bullies of the World" | 1:22 |

| 9. | "Shane's Song" | 2:03 |

| 10. | "Dinosaurs in the Bible" | 5:45 |

| 11. | "Living God" | 1:05 |

| 12. | "Marketing & Advertising" | 4:38 |

| 13. | "Don't Talk for Me" | 1:40 |

| 14. | "Clam Lappers & Sonic the Hedgehog" | 3:02 |

| 15. | "She's Got a Broken Heart" | 1:09 |

| 16. | "Pussywhipped Satan" | 4:40 |

| 17. | "L.A. Falls" | 3:54 |

| 18. | "Elvis" | 8:05 |

Arizona Bay Extended

[edit]| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Intro" | 2:03 |

| 2. | "Arizona Bay" | 0:50 |

| 3. | "Goodbye You Lizard Scum" | 2:15 |

| 4. | "Ha-Ha Los Angeles" | 1:11 |

| 5. | "Step on the Gas (L.A. Riots)" | 3:44 |

| 6. | "Hooligans" | 1:27 |

| 7. | "Officer Nigger Hater" | 5:46 |

| 8. | "As Long as We're Talking Shelf Life (Kennedy)" | 4:16 |

| 9. | "The Elephant Is Dead (Bush)" | 3:03 |

| 10. | "Deficit - Tighten the Belt" | 1:19 |

| 11. | "Me & Saddam" | 0:50 |

| 12. | "Dinosaurs in the Bible" | 6:00 |

| 13. | "Fetus on TV" | 1:21 |

| 14. | "Abortion" | 0:52 |

| 15. | "Bring Granny to the Show" | 0:31 |

| 16. | "I Quit Smoking" | 1:09 |

| 17. | "Old Smoker in Central Park" | 0:36 |

| 18. | "Smoking in L.A. (No Tolerance)" | 1:19 |

| 19. | "No Smoking on Airplanes (But They Allow Children)" | 3:58 |

| 20. | "We're Recording an Album Tonight" | 0:20 |

| 21. | "Going for the Record (Nothing but Air)" | 1:02 |

| 22. | "Marketing & Advertising" | 1:56 |

| 23. | "Basic Instinct" | 6:52 |

| 24. | "Goatboy" | 3:08 |

| 25. | "Clam Lappers & Sonic the Hedgehog" | 1:54 |

| 26. | "Goatboy Revisited" | 0:55 |

| 27. | "I Blame the Women" | 2:00 |

| 28. | "Pussywhipped Satan" | 2:41 |

| 29. | "Microphone Is Getting Lower" | 0:43 |

| 30. | "Charlie Hodge" | 8:39 |

Personnel

[edit]- Bill Hicks - guitar, vocals

- Kevin Booth - bass, keyboards, percussion, producer

References

[edit]- ^ AllMusic review

- ^ "BILL HICKS' LEGACY OF THE PROFANE AND THE PROFOUND OUT ON CD - Chicago Tribune".

- ^ Map of America, showing "Arizona Bay", video shot and narrated by Bill Hicks at Fossil Creek Studio in Austin, Texas, during the Arizona Bay recording sessions (music elements), November 1992 (SacredCowProductions, uploaded to YouTube on Feb 26, 2014).

- ^ "Arizona Bay Extended". Comedy Dynamics. Retrieved February 8, 2019.

- ^ a b "Bill Hicks Biography page". billhicks.com. Archived from the original on June 26, 2018. Retrieved April 30, 2016.

- ^ Tool FAQ

Arizona Bay

View on GrokipediaBackground

Conception and Hicks' career context

By the early 1990s, Bill Hicks had established himself as a provocative stand-up comedian known for his incisive social and political commentary, following the release of his debut album Dangerous in 1990 and Relentless in 1992, both captured live during performances.[3] These works showcased his raw, unfiltered style, but Hicks sought to evolve beyond standard live recordings, drawing on his growing international following—particularly in the UK, where he completed sell-out seasons at London's Dominion Theatre in 1992 and 1993, including the filmed special Revelations.[9] [10] His US career, however, encountered resistance, highlighted by his October 1, 1993, appearance on Late Show with David Letterman, where CBS censored the entire six-minute set for its critiques of religion, politics, and marketing, marking the first such instance for a comedy routine on the program.[11] [12] In this context, Hicks conceived Arizona Bay as a more ambitious, conceptual project departing from his prior live albums, incorporating original instrumental music he composed alongside comedy routines to create a narrative arc.[3] The album's central premise stemmed from Hicks' recurring satirical fantasy of a massive earthquake—"the big one"—causing Los Angeles and California to submerge into the Pacific Ocean, literally forming "Arizona Bay" and symbolizing his disdain for Hollywood superficiality, consumerism, and cultural decay while envisioning a post-apocalyptic reset aligned with his philosophical interests in spirituality and human potential.[13] This idea, which Hicks had explored in live routines, extended into a structured "sonic portrait" of life on the resulting beachfront, blending humor with ambient soundscapes to critique societal illusions.[14] Recording for Arizona Bay took place in Austin, Texas, during 1993, coinciding with Hicks' diagnosis of pancreatic cancer in June of that year, after which he underwent chemotherapy but persisted with creative work and touring.[9] Despite his deteriorating health, Hicks completed the sessions before his final performances, viewing the project as a culmination of his evolving artistry amid professional frustrations and personal mortality.[15] The album's posthumous release in 1997 thus preserved this late-career innovation, unhindered by the commercial music additions that marred some initial bootlegs.[4]Recording and production

The musical components of Arizona Bay were recorded at Fossil Creek Studio in Austin, Texas, from November 1992 to June 1993, featuring Bill Hicks on guitar and vocals alongside collaborator Kevin Booth on bass, keyboards, percussion, drums, and sound effects.[16][17] Booth also served as producer and engineer for these sessions, which aimed to integrate original instrumental tracks with Hicks' stand-up routines to create a conceptual album envisioning a post-apocalyptic coastal landscape following California's hypothetical submersion into the Pacific Ocean.[16][13] The comedy segments were drawn from live performances captured at venues including the Laff Stop in Houston, reflecting Hicks' ongoing touring material from his final years.[16] After Hicks' death from pancreatic cancer on February 26, 1994, Booth oversaw the posthumous assembly and finalization of the album at Sacred Cow Productions, incorporating editing to alternate music and monologue for thematic cohesion.[16][15] Executive production was handled by Hicks' mother, Mary Reese Hicks, who managed archival selections and approvals.[16] Mastering occurred at Cedar Creek Recording in Austin, credited to Fred Remmert and Kevin Booth, ensuring audio fidelity across the hybrid format of spoken-word tracks and ambient soundscapes.[16] The production emphasized Hicks' vision of an innovative, non-traditional comedy release, diverging from his prior live-only albums by blending studio instrumentation with raw performance audio.[4]Content

Core themes and philosophical underpinnings

Arizona Bay centers on a satirical fantasy of Los Angeles submerging into the Pacific Ocean following a massive earthquake, an event Hicks portrayed as cleansing American culture of Hollywood's dominance. This conceit underscores his critique of the entertainment industry as a purveyor of superficiality and escapism, arguing that its elimination would foster greater authenticity in human expression.[6] The album intersperses comedy routines with musical interludes to depict a post-catastrophe landscape, emphasizing themes of renewal amid destruction.[13] Philosophically, the work reflects Hicks' conviction that consumer-driven media stifles spiritual and intellectual growth, echoing his recurring motif of marketing as an evolutionary barrier akin to the monolith in 2001: A Space Odyssey. Routines target political absurdities, such as the Kennedy assassination and presidential policies under George H.W. Bush, portraying government and elites as complicit in maintaining illusions of control.[18] Hicks advocated transcending these through personal enlightenment, often alluding to psychedelics and introspection as paths to higher consciousness, free from institutionalized dogma.[19] Underlying these elements is a libertarian-leaning skepticism of centralized authority and cultural conformity, positioning individual awakening as the antidote to societal decay. Hicks' humor in Arizona Bay serves not mere provocation but a call to reject commodified reality, aligning with his broader oeuvre's emphasis on causal links between media manipulation and curtailed human potential.[20] This vision posits catastrophe as paradoxical liberation, prioritizing empirical observation of cultural influences over normative politeness.Key routines and structure

Arizona Bay employs a conceptual structure that intersperses Hicks' live stand-up routines with original instrumental tracks composed by Hicks alongside Kevin Booth, creating an auditory depiction of a post-apocalyptic coastal scene following a hypothetical earthquake that submerges California into the Pacific Ocean, thereby forming "Arizona Bay" as new waterfront territory. This alternating format, totaling 18 tracks across approximately 66 minutes, uses ambient music interludes—featuring synthesized waves, percussion, and ethereal tones—to transition between comedy segments, evoking a meditative, serene aftermath amid societal critique.[21][2] The comedy routines, drawn from Hicks' 1992-1993 performances, predominantly target American politics, culture, and social hypocrisies. Opening with "Goodbye You Lizard Scum," a surreal intro dismissing superficial concerns, the album progresses to "Step on the Gas (L.A. Riots)," where Hicks lampoons media sensationalism and public outrage during the 1992 Los Angeles riots following the Rodney King verdict.[1][5] "Hooligans" skewers aggressive fan behavior in sports and entertainment, while "Officer Nigger Hater" employs raw, confrontational language to expose entrenched racism and authoritarian policing dynamics.[1] Political satire dominates later segments, including "Elephant Is Dead (Bush)," a takedown of President George H.W. Bush's administration and foreign policy missteps; "Me and Saddam," mocking U.S.-Iraq relations amid the Gulf War buildup; and "Bullies of the World," critiquing American interventionism as global hegemony.[5] "As Long as We're Talking Shelf Life (Kennedy)" extends Hicks' recurring conspiracy-inflected commentary on the JFK assassination, questioning official narratives. These routines, delivered in Hicks' signature intense, stream-of-consciousness style, interconnect through the album's overarching motif of cultural collapse and renewal.[5]Release

Posthumous issuance and marketing

Arizona Bay was issued posthumously on February 25, 1997, through Rykodisc's Voices imprint, compiling live stand-up recordings from Bill Hicks' performances in 1992 and 1993 alongside original instrumental tracks he composed on acoustic guitar and piano.[22][23] The release occurred three years after Hicks' death from pancreatic cancer on February 26, 1994, with production overseen by his estate to realize his pre-death vision of an album alternating comedy routines with music to depict a post-apocalyptic "Arizona Bay" formed by California's submersion.[18][13] Rykodisc's marketing emphasized Hicks' status as a visionary satirist with an expanding cult audience, particularly among those drawn to his critiques of consumerism, religion, and media, which had gained traction via bootlegs and UK broadcasts post-death.[24] The label bundled the album's launch with the simultaneous release of Hicks' Rant in E-Minor and remastered CD editions of his earlier works, Dangerous (1990) and Relentless (1992), to position Arizona Bay within a fuller retrospective that highlighted his philosophical depth and uncompromised style for broader commercial accessibility.[25][26] This coordinated catalog push targeted niche comedy enthusiasts and countercultural listeners, leveraging Hicks' posthumous reputation for raw, introspective material unavailable during his lifetime due to limited mainstream distribution.[4] Subsequent licensing to entities like Comedy Dynamics sustained availability through digital platforms and expanded editions, reflecting ongoing interest without aggressive mainstream promotion.[13]Initial distribution challenges

Following its posthumous completion by collaborator Kevin Booth to align with Hicks' specifications, Arizona Bay faced initial distribution challenges inherent to releasing an unreleased, experimental comedy album blending stand-up with original music interludes three years after the artist's death from pancreatic cancer on February 26, 1994. Rykodisc, an independent label specializing in alternative and reissue titles, issued the album on CD on February 25, 1997—timed to coincide with the third anniversary of Hicks' passing—to capitalize on commemorative interest.[27][2][8] The label bundled Arizona Bay with the similarly posthumous Rant in E-Minor, Hicks' other unfinished project, alongside reissues of Dangerous (1990) and Relentless (1992), to leverage cross-promotion and appeal to Hicks' existing underground fanbase amid limited mainstream visibility. Without live performances, interviews, or artist-driven marketing—standard for comedy albums—distribution depended on Rykodisc's network of independent record stores, mail-order catalogs, and emerging online channels, rather than broad chain retailer stocking or radio support, given the material's profane language and anti-establishment themes. This approach ensured availability but constrained initial reach to niche audiences, with sales building gradually through fan word-of-mouth and print reviews rather than aggressive retail push.[28][4] Despite these constraints, Rykodisc achieved a wide commercial rollout for the era's standards in spoken-word comedy, avoiding outright censorship but navigating retailer hesitancy toward explicit content in a pre-streaming market dominated by music genres. The album's structure, featuring raw live recordings interspersed with Hicks' amateurish guitar and piano segments, further complicated appeal to conventional distributors accustomed to polished productions, yet it preserved the intended conceptual arc of post-apocalyptic satire.[13][4]Reception

Contemporary reviews and audience reactions

Upon its March 1997 release, Arizona Bay received positive notices in specialized music and alternative press outlets, which highlighted its conceptual coherence as a "comic concept album" blending stand-up routines with instrumental tracks envisioning a post-earthquake "Arizona Bay" after California's submersion.[29] Reviewers praised Hicks' guitar work and vocal contributions alongside collaborator Kevin Booth, noting the material's fearless edge on topics like the Rodney King trial, the L.A. riots, and U.S.-Iraq relations, informed by Hicks' terminal cancer diagnosis during production.[29] AllMusic critic Brian Flota described it as Hicks' "most consistently funny CD," appreciating routines ridiculing Los Angeles culture, Republican politics ("The Elephant Is Dead"), fundamentalist Christianity ("Dinosaurs in the Bible"), and marketing professionals—whom Hicks urged to "kill themselves" in a bit subverted by an "anti-marketing dollar" punchline—while acknowledging personal anecdotes on emotional "arrested development" via pornography and video games.[30] Flota contrasted its steady humor with the "fiery intensity" of companion release Rant in E-Minor but critiqued occasional intrusive musical interludes amid 1992-sourced performances.[30] Mainstream media coverage remained limited, reflecting the album's niche appeal in stand-up comedy and posthumous status three years after Hicks' 1994 death from pancreatic cancer, though it aligned with his established cult following from prior works like Relentless (1992).[30] Audience responses among existing fans were enthusiastic, valuing the realization of Hicks' ambitious "Dark Side of the Moon"-inspired structure alternating comedy and music to depict apocalyptic aftermath and philosophical renewal, which resonated as a capstone to his oeuvre despite production quibbles over musical integration.[29] Early listener feedback echoed critical appreciation for its satirical bite against consumerism and authority, fostering discussions in alternative zines and comedy circles about Hicks' enduring relevance in critiquing societal absurdities.[29]Commercial metrics and sales data

Arizona Bay, released on February 25, 1997, by Rykodisc's Voices imprint, did not enter major commercial charts such as the Billboard 200 or Comedy Albums rankings.[30] [8] Specific sales figures for the album are not publicly documented or certified by organizations like the RIAA, consistent with Bill Hicks' oeuvre appealing primarily to a cult audience rather than achieving broad market penetration.[2] The posthumous issuance, paired with the simultaneous release of Rant in E-Minor, aimed to consolidate Hicks' recorded material but yielded modest revenue in the niche stand-up comedy sector, where physical album sales in the late 1990s were dwarfed by mainstream genres.[13] Long-term metrics indicate steady but low-volume sales driven by fan reissues, digital streaming, and inclusions in box sets like the 2015 Complete Collection, though exact units remain unreported.[31] This performance underscores Hicks' enduring but commercially marginal status, with no evidence of gold or platinum certifications across his discography.Controversies

Offensiveness claims and censorship attempts

Hicks' routines compiled for Arizona Bay, recorded in late 1993, included sharp critiques of organized religion, consumerism, and political hypocrisy, which drew accusations of offensiveness from conservative and religious audiences. For instance, segments mocking fundamentalist Christianity, such as portrayals of biblical literalism and televangelism, were labeled blasphemous by critics who viewed them as attacks on faith itself rather than institutions.[32] A Texas priest wrote to Hicks in 1990 decrying his live show content as "blasphemous" for ridiculing sacred doctrines, a sentiment echoed in responses to similar material on the album like "Fundamentalist Christians" and apocalyptic preacher-style rants.[33] These claims stemmed from Hicks' deliberate provocation, framing religion as a tool for control, though supporters argued his intent was philosophical inquiry into dogma versus personal spirituality.[9] Censorship attempts tied to Arizona Bay-era material peaked with Hicks' October 30, 1993, appearance on Late Show with David Letterman, taped just after initial recordings for the project. The set featured the "Goat Boy" routine—a satirical fusion of religious imagery, sex, and devilish temptation—alongside a quip about then-President George H.W. Bush's daughter potentially seeking an abortion, which network executives deemed too inflammatory for broadcast.[11] This marked the first comedy censorship at CBS's Ed Sullivan Theater since Elvis Presley's 1956 hip-swiveling performance, with the entire five-minute segment pulled post-taping despite Hicks' prior 11 unchallenged appearances.[11] Letterman later attributed the decision to sponsor pressure and internal CBS concerns over abortion references amid Clinton-era culture wars, though Hicks publicly contested it as yielding to advertiser influence.[34] Posthumously, no formal censorship attempts targeted Arizona Bay's 1997 release; Hicks' estate, managed by family including brother Steve Hicks, prioritized unedited distribution via Rykodisc (later Comedy Dynamics), preserving raw tracks despite their potential to offend.[9] This contrasted with pre-death pressures, allowing controversial bits on topics like the LA riots ("Step on the Gas") and conspiracy-laden "lizard" elites to stand unaltered, though some reviewers noted the material's intensity risked alienating mainstream listeners.[4] The absence of edits reflected Hicks' final wishes for authenticity, as outlined in his pre-death statements emphasizing uncompromised truth-telling over palatability.[9]Interpretations of Hicks' worldview

Hicks' worldview, as interpreted through Arizona Bay, centers on a libertarian critique of corporate-driven consumerism and media manipulation, portraying American society as a mechanism of cultural homogenization that alienates individuals from authentic experience. In the title routine, he fantasizes about an earthquake submerging Los Angeles, eradicating Hollywood's superficial elite—satirically dubbed "lizard people"—to usher in a liberated coastal utopia of communal music, marijuana use, and introspection, free from commodified entertainment.[20] This vision, recorded in live performances from 1993, reflects his broader rejection of mass culture as a "Third World consumer fucking plantation," where capitalism reduces human potential to profit-driven illusions, echoing analyses of the culture industry as a tool for ideological control.[20] [35] Philosophically, Hicks advocated "revoevolution"—a micropolitical shift toward individual cognitive autonomy and subjective reality construction—over hierarchical or dogmatic systems, aligning with anarchist principles that prioritize personal responsibility against state and corporate overreach.[20] Routines like "Waco (Koresh)" extend this by linking government actions, such as the 1993 siege, to consumption-fueled oppression, urging listeners to question propagated narratives of events like the Gulf War.[20] Interpreters note his emphasis on doubt as a liberating force, articulating skepticism toward patriotism, militarism, and institutional authority to foster unfiltered truth-seeking, though critics have occasionally misread this as endorsing chaos rather than intellectual anarchy.[35] [36] Regarding spirituality and religion, Hicks dismissed organized Christianity as fear-based dogma that stifles reason, favoring an internal "voice of reason" and self-determined meaning derived from personal exploration, including psychedelics, over transcendental absolutes.[20] In Arizona Bay, this manifests in routines promoting non-dogmatic unity and critique of fundamentalist misinterpretations of texts, positioning spirituality as emergent from individual consciousness rather than institutional mediation—a stance some view as pantheistic or influenced by Eastern non-dualism, though Hicks grounded it in empirical self-inquiry against imposed binaries.[20] Such interpretations underscore his comedy's role in challenging perceptual distortions, advocating freedoms like drug legalization as pathways to genuine human connection, provided no harm ensues.[36]Legacy

Influence on comedy and counterculture

Arizona Bay's integration of stand-up routines with musical interludes showcased Bill Hicks' innovative approach to comedy, blending narrative storytelling, rhythmic delivery, and thematic depth in tracks like the anti-marketing segment, which highlighted his precise control over pauses and tonal shifts developed from over 200 annual performances since age 17.[9] This stylistic mastery influenced subsequent comedians; Louis C.K. echoed Hicks' handling of provocative sexual material through similar pauses and unfiltered introspection, while Jon Stewart adopted comparable structures for truth-to-power critiques, building on Hicks' confrontational rhythm evident in the album's 1993 recordings.[9] Released posthumously on October 14, 1997, the album preserved these techniques, allowing Hicks' method of dissecting societal absurdities—such as consumerism and media manipulation—to permeate stand-up traditions beyond his lifetime. Thematically, Arizona Bay advanced countercultural discourse by framing Los Angeles' hypothetical submersion in an earthquake as a metaphorical reset against commercial excess, with Hicks' guitar-accompanied visions alternating between satire and philosophical musings on human potential unhindered by materialism.[13] This conceptual structure, recorded in 1993, reinforced Hicks' rejection of market-driven ideologies, fostering a legacy of moral unconstrained commentary that resonated with audiences seeking alternatives to mainstream conformity.[9] Its enduring relevance, affirmed in the 2015 rerelease, lies in sustaining Hicks' status as a countercultural touchstone, where routines critiquing religious hypocrisy and political theater encouraged later performers to prioritize substantive provocation over palatable entertainment.[9]Ties to music, particularly Tool's Ænima

The concept central to Bill Hicks' Arizona Bay—a speculative apocalyptic vision of Los Angeles sinking into the Pacific Ocean, thereby forming a new inland sea called Arizona Bay—originated in Hicks' live comedy routines performed in the early 1990s, well before the album's posthumous release on March 11, 1997. This routine critiqued Hollywood's cultural superficiality and environmental hubris, positing the event as a purifying reset for American society.[37] American progressive metal band Tool incorporated direct references to this idea in their 1996 album Ænima, released on September 17, 1996, which was explicitly dedicated to Hicks following his death from pancreatic cancer on February 26, 1994.[38] The album's title track, "Ænema," features lyrics such as "Bye-bye L.A. / We're going to Arizona Bay / Won't see your tail lights burnin' / For many a mile," echoing Hicks' phrasing and imagery almost verbatim.[39] Tool frontman Maynard James Keenan developed a personal friendship with Hicks after encountering him at the 1993 Lollapalooza festival, where both performed; they discussed potential joint touring plans before Hicks' illness prevented it.[40] Keenan has cited Hicks as a philosophical influence, crediting his routines for inspiring Ænima's themes of societal critique, personal transcendence, and disdain for celebrity culture, as evidenced by the band's earlier nod to Hicks in the liner notes of their 1993 album Undertow.[41] The Ænima packaging further nods to Hicks with an inlay illustration depicting a flooded California coastline, mirroring his "Arizona Bay" sketch.[37] While Ænima predates Arizona Bay's release, the shared motifs underscore Hicks' broader impact on Tool's oeuvre, blending misanthropic humor with metaphysical inquiry—elements Keenan described as aligning with the band's message of awakening from illusion.[42] Beyond Ænema, Hicks' influence permeates other Ænima tracks, such as "Third Eye," which explores expanded consciousness in ways resonant with Hicks' advocacy for psychedelic experiences and rejection of dogmatic thinking.[43] This connection has been attributed by Keenan not as direct lyrical borrowing but as a convergence of worldviews, with Hicks' unfiltered social commentary providing a comedic counterpoint to Tool's dense, introspective soundscapes.[39] The ties elevated Hicks' posthumous visibility in alternative music circles, fostering fan crossovers and remixes pairing Hicks' audio with Tool's instrumentation, though Tool has maintained the influence as inspirational rather than collaborative.[44]Track listing

Standard edition

The standard edition of Arizona Bay, released on February 25, 1997, by Rykodisc, comprises 18 live comedy routines interspersed with original music composed by Bill Hicks.[2][8] The album runs approximately 66 minutes and was compiled from performances recorded between November 22, 1992, and June 1993 at the Laff Stop in Houston, Texas.[18]| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | "Goodbye You Lizard Scum" | 3:52 |

| 2 | "Step on the Gas (L.A. Riots)" | 4:51 |

| 3 | "Hooligans" | 4:21 |

| 4 | "Officer Nigger Hater" | 5:27 |

| 5 | "As Long as We're Talking Shelf Life (Kennedy)" | 5:00 |

| 6 | "The Elephant Is Dead (Bush)" | 1:58 |

| 7 | "Me & Saddam" | 3:11 |

| 8 | "Bullies of the World" | 1:22 |

| 9 | "Shane's Song" | 2:03 |

| 10 | "Dinosaurs in the Bible" | 5:46 |

| 11 | "Living God" | 1:06 |

| 12 | "Marketing & Advertising" | 4:38 |

| 13 | "Don't Talk for Me" | 1:40 |

| 14 | "Clam Lappers & Sonic the Hedgehog™" | 3:02 |

| 15 | "She's Got a Broken Heart" | 1:09 |

| 16 | "Pussywhipped Satan" | 4:40 |

| 17 | "L.A. Falls" | 3:54 |

| 18 | "Elvis" | 8:05 |