Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Biribi

View on Wikipedia

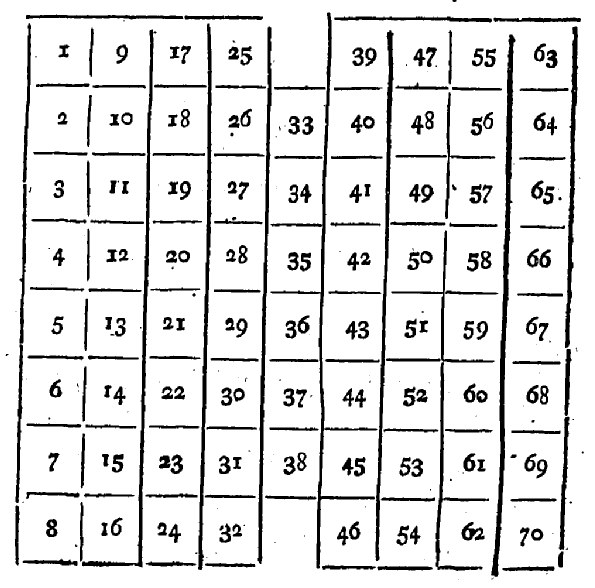

Biribi, biribissi (in Italian), or cavagnole (in French), is an Italian game of chance similar to keno, played for low stakes. It is played on a board on which the numbers 1 to 70 are marked.[1] The game was banned in Italy in 1837.

The players put their stakes on the numbers they wish to back. The banker is provided with a bag from which he draws a case containing a ticket, the tickets corresponding with the numbers on the board. The banker calls out the number, and any players who backed it receive sixty-four times their stake; all other stakes go to the banker.[2]

Casanova played it in Genoa (illegally, for it was already banned there) and the South of France in the 1760s, and describes it as "a regular cheats' game".[3][4] He broke the bank (fairly, he claims) and was immediately rumored to have been in collusion with the bag-holder; such collusion, presumably, was common.[5]

In the French army, "to be sent to Biribi" was a cant term for being sent to the disciplinary battalions in Algeria.[2]

References

[edit]- ^ Dumas, Alexandre (1998). Twenty Years After. Oxford University Press, UK. pp. 836–. ISBN 978-0-19-283843-8. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- ^ a b One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Biribi". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 981.

- ^ "Manuscript Biribi Game from the 18th century". Antiquariat | Steffen Völkel GmbH (in German). Retrieved 2024-07-17.

- ^ The Memoirs of Jacques Casanova (Volume 5)

- ^ Lathan, Sharon (2016-07-11). "Cavagnole". Sharon Lathan, Novelist. Retrieved 2024-07-17.