Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Roulette

View on Wikipedia

Roulette (named after the French word meaning "little wheel") is a casino game which was likely developed from the Italian game Biribi. In the game, a player may choose to place a bet on a single number, various groupings of numbers, the color red or black, whether the number is odd or even, or if the number is high or low.

To determine the winning number, a croupier spins a wheel in one direction, then spins a ball in the opposite direction around a tilted circular track running around the outer edge of the wheel. The ball eventually loses momentum, passes through an area of deflectors, and falls onto the wheel and into one of the colored and numbered pockets on the wheel. The winnings are then paid to anyone who has placed a successful bet.

History

[edit]

The first form of roulette was devised in 18th-century France. Many historians believe Blaise Pascal introduced a primitive form of roulette in the 17th century in his search for a perpetual motion machine.[1] The roulette mechanism is a hybrid of a gaming wheel invented in 1720 and the Italian game Biribi.[2] A primitive form of roulette, known as "EO" (Even/Odd), was played in England in the late 18th century using a gaming wheel similar to that used in roulette.[3]

The game has been played in its present form since as early as 1796 in Paris. An early description of the roulette game in its current form is found in a French novel La Roulette, ou le Jour by Jaques Lablee, which describes a roulette wheel in the Palais Royal in Paris in 1796. The description included the house pockets: "There are exactly two slots reserved for the bank, whence it derives its sole mathematical advantage." It then goes on to describe the layout with "two betting spaces containing the bank's two numbers, zero and double zero". The book was published in 1801. An even earlier reference to a game of this name was published in regulations for New France (Québec) in 1758, which banned the games of "dice, hoca, faro, and roulette".[4]

The roulette wheels used in the casinos of Paris in the late 1790s had red for the single zero and black for the double zero. To avoid confusion, the color green was selected for the zeros in roulette wheels starting in the 1800s.

In 1843, in the German spa casino town of Bad Homburg, fellow Frenchmen François and Louis Blanc introduced the single 0 style roulette wheel in order to compete against other casinos offering the traditional wheel with single and double zero house pockets.

In some forms of early American roulette wheels, there were numbers 1 to 28, plus a single zero, a double zero, and an American Eagle. The Eagle slot, which was a symbol of American liberty, was a house slot that brought the casino an extra edge. Soon, the tradition vanished and since then the wheel features only numbered slots. According to Hoyle "the single 0, the double 0, and the eagle are never bars; but when the ball falls into either of them, the banker sweeps every thing upon the table, except what may happen to be bet on either one of them, when he pays twenty-seven for one, which is the amount paid for all sums bet upon any single figure".[5]

In the 19th century, roulette spread all over Europe and the US, becoming one of the most popular casino games. When the German government abolished gambling in the 1860s, the Blanc family moved to the last legal remaining casino operation in Europe at Monte Carlo, where they established a gambling mecca for the elite of Europe. It was here that the single zero roulette wheel became the premier game, and over the years was exported around the world, except in the United States where the double zero wheel remained dominant.

In the United States, the French double zero wheel made its way up the Mississippi from New Orleans, and then westward. It was here, because of rampant cheating by both operators and gamblers, that the wheel was eventually placed on top of the table to prevent devices from being hidden in the table or wheel, and the betting layout was simplified. This eventually evolved into the American-style roulette game. The American game was developed in the gambling dens across the new territories where makeshift games had been set up, whereas the French game evolved with style and leisure in Monte Carlo.

During the first part of the 20th century, the only casino towns of note were Monte Carlo with the traditional single zero French wheel, and Las Vegas with the American double zero wheel. In the 1970s, casinos began to flourish around the world. In 1996 the first online casino, generally believed to be InterCasino, made it possible to play roulette online.[6] By 2008, there were several hundred casinos worldwide offering roulette games. The double zero wheel is found in the United States, Canada, South America, and the Caribbean, while the single zero wheel is predominant elsewhere.

Rules of play against a casino

[edit]

Roulette players have a variety of betting options. "Inside" bets involve selecting either the exact number on which the ball will land, or a small group of numbers adjacent to each other on the layout. "Outside" bets, by contrast, allow players to select a larger group of numbers based on properties such as their color or parity (odd/even). The payout odds for each type of bet are based on its probability.

The roulette table usually imposes minimum and maximum bets, and these rules usually apply separately for all of a player's inside and outside bets for each spin. For inside bets at roulette tables, some casinos may use separate roulette table chips of various colors to distinguish players at the table. Players can continue to place bets as the ball spins around the wheel until the dealer announces "no more bets" or "rien ne va plus".

When a winning number and color is determined by the roulette wheel, the dealer will place a marker, also known as a dolly, on that number on the roulette table layout. When the dolly is on the table, no players may place bets, collect bets or remove any bets from the table. The dealer will then sweep away all losing bets either by hand or by rake, and determine the payouts for the remaining inside and outside winning bets. When the dealer is finished making payouts, the dolly is removed from the board and players may collect their winnings and make new bets. Winning chips remain on the board until picked up by a player.

California Roulette

[edit]In 2004, California legalized a form of roulette known as California Roulette.[7] By law, the game must use cards and not slots on the roulette wheel to pick the winning number.

Roulette wheel number sequence

[edit]The pockets of the roulette wheel are numbered from 0 to 36.

In number ranges from 1 to 10 and 19 to 28, odd numbers are red and even are black. In ranges from 11 to 18 and 29 to 36, odd numbers are black and even are red.

There is a green pocket numbered 0 (zero). In American roulette, there is a second green pocket marked 00. Pocket number order on the roulette wheel adheres to the following clockwise sequence in most casinos:[citation needed]

- Single-zero wheel

- 0-32-15-19-4-21-2-25-17-34-6-27-13-36-11-30-8-23-10-5-24-16-33-1-20-14-31-9-22-18-29-7-28-12-35-3-26

- Double-zero wheel

- 0-28-9-26-30-11-7-20-32-17-5-22-34-15-3-24-36-13-1-00-27-10-25-29-12-8-19-31-18-6-21-33-16-4-23-35-14-2

- Triple-zero wheel

- 0-000-00-32-15-19-4-21-2-25-17-34-6-27-13-36-11-30-8-23-10-5-24-16-33-1-20-14-31-9-22-18-29-7-28-12-35-3-26

Roulette table layout

[edit]This section's factual accuracy is disputed. (July 2022) |

The cloth-covered betting area on a roulette table is known as the layout. The layout is either single-zero or double-zero.

The European-style layout has a single zero, and the American style layout is usually a double-zero. The American-style roulette table with a wheel at one end is now used in most casinos because it has a higher house edge compared to a European layout.[8]

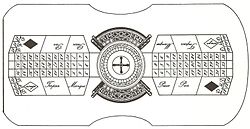

The French style table with a wheel in the centre and a layout on either side is rarely found outside of Monte Carlo.

Types of bets

[edit]In roulette, bets can be either inside or outside.[9]

Inside bets

[edit]| Name | Description | Chip placement |

|---|---|---|

| Straight/single | Bet on a single number | Entirely within the square for the chosen number |

| Split | Bet on two vertically/horizontally adjacent numbers (e.g. 14-17 or 8–9) | On the edge shared by the numbers |

| Street | Bet on three consecutive numbers in a horizontal line (e.g. 7-8-9) | On the outer edge of the number at either end of the line |

| Corner/square | Bet on four numbers that meet at one corner (e.g. 10-11-13-14) | On the common corner |

| Six line/double street | Bet on six consecutive numbers that form two horizontal lines (e.g. 31-32-33-34-35-36) | On the outer corner shared by the two leftmost or the two rightmost numbers |

| Trio/basket | A three-number bet that involves at least one zero: 0-1-2 (either layout); 0-2-3 (single-zero only); 0-00-2 and 00-2-3 (double-zero only) | On the corner shared by the three chosen numbers |

| First four | Bet on 0-1-2-3 (single-zero layout only) | On the outer corner shared by 0-1 or 0-3 |

| Top line | Bet on 0-00-1-2-3 (double-zero layout only) | On the outer corner shared by 0-1 or 00-3 |

Outside bets

[edit]Outside bets typically have smaller payouts with better odds at winning. Except as noted, all of these bets lose if a 0 comes up.

- 1 to 18 (low or manque), or 19 to 36 (high or passe)

- A bet that the number will be in the chosen range.

- Red or black (rouge ou noir)

- A bet that the number will be the chosen color.

- Even or odd (pair ou impair)

- A bet that the number will be of the chosen parity. Unlike in mathematics, in Roulette 0 is considered neither even nor odd.

- Dozen bet

- A bet that the number will be in the chosen dozen: first (1-12, Première douzaine or P12), second (13-24, Moyenne douzaine or M12), or third (25-36, Dernière douzaine or D12).

- Column bet

- A bet that the number will be in the chosen vertical column of 12 numbers, such as 1-4-7-10 on down to 34. The chip is placed on the space below the final number in this sequence.

- Snake bet

- A special bet that covers the numbers 1, 5, 9, 12, 14, 16, 19, 23, 27, 30, 32, and 34. It has the same payout as the dozen bet and takes its name from the zig-zagging, snakelike pattern traced out by these numbers. The snake bet is not available in all casinos; when it is allowed, the chip is placed on the lower corner of the 34 square that borders the 19-36 betting box. Some layouts mark the bet with a two-headed snake that winds from 1 to 34, and the bet can be placed on the head at either end of the body.

In some casinos, the farthest outside bets (low/high, red/black, even/odd) result in the player losing only half of their bet if a zero comes up. This is known as the "halfback" or la partage rule. Others may use an "imprisonment" or en prison rule, wherein a loss on such an outside bet causes the player's money to be "imprisoned", and if the next spin would be a win for that bet, the player's wager is returned.

Bet odds table

[edit]The expected value of a $1 bet (except for the special case of top line bets), for American and European roulette, can be calculated as

where n is the number of pockets in the wheel.

The initial bet is returned in addition to the mentioned payout: it can be easily demonstrated that this payout formula would lead to a zero expected value of profit if there were only 36 numbers (that is, the casino would break even). Having 37 or more numbers gives the casino its edge.

| Bet name | Winning spaces | Payout | French | American | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds against winning | Expected value (on $1 bet) |

Odds against winning | Expected value (on $1 bet) | |||

| 0 | 0 | 35 to 1 | 36 to 1 | −$0.027 | 37 to 1 | −$0.053 |

| 00 | 00 | 35 to 1 | 37 to 1 | −$0.053 | ||

| Straight up | Any single number | 35 to 1 | 36 to 1 | −$0.027 | 37 to 1 | −$0.053 |

| Row | 0, 00 | 17 to 1 | 18 to 1 | −$0.053 | ||

| Split | Any two adjoining numbers vertical or horizontal | 17 to 1 | 17+1⁄2 to 1 | −$0.027 | 18 to 1 | −$0.053 |

| Street | Any three numbers horizontal (1, 2, 3 or 4, 5, 6, etc.) | 11 to 1 | 11+1⁄3 to 1 | −$0.027 | 11+2⁄3 to 1 | −$0.053 |

| Corner | Any four adjoining numbers in a block (1, 2, 4, 5 or 17, 18, 20, 21, etc.) | 8 to 1 | 8+1⁄4 to 1 | −$0.027 | 8+1⁄2 to 1 | −$0.053 |

| Top line (US) | 0, 00, 1, 2, 3 | 6 to 1 | 6+3⁄5 to 1 | −$0.079 | ||

| Top line (European) | 0, 1, 2, 3 | 8 to 1 | 8+1⁄4 to 1 | −$0.027 | ||

| Double street | Any six numbers from two horizontal rows (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 or 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33 etc.) | 5 to 1 | 5+1⁄6 to 1 | −$0.027 | 5+1⁄3 to 1 | −$0.053 |

| 1st column | 1, 4, 7, 10, 13, 16, 19, 22, 25, 28, 31, 34 | 2 to 1 | 2+1⁄12 to 1 | −$0.027 | 2+1⁄6 to 1 | −$0.053 |

| 2nd column | 2, 5, 8, 11, 14, 17, 20, 23, 26, 29, 32, 35 | 2 to 1 | 2+1⁄12 to 1 | −$0.027 | 2+1⁄6 to 1 | −$0.053 |

| 3rd column | 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, 21, 24, 27, 30, 33, 36 | 2 to 1 | 2+1⁄12 to 1 | −$0.027 | 2+1⁄6 to 1 | −$0.053 |

| 1st dozen | 1 through 12 | 2 to 1 | 2+1⁄12 to 1 | −$0.027 | 2+1⁄6 to 1 | −$0.053 |

| 2nd dozen | 13 through 24 | 2 to 1 | 2+1⁄12 to 1 | −$0.027 | 2+1⁄6 to 1 | −$0.053 |

| 3rd dozen | 25 through 36 | 2 to 1 | 2+1⁄12 to 1 | −$0.027 | 2+1⁄6 to 1 | −$0.053 |

| Odd | 1, 3, 5, ..., 35 | 1 to 1 | 1+1⁄18 to 1 | −$0.027 | 1+1⁄9 to 1 | −$0.053 |

| Even | 2, 4, 6, ..., 36 | 1 to 1 | 1+1⁄18 to 1 | −$0.027 | 1+1⁄9 to 1 | −$0.053 |

| Red | 32, 19, 21, 25, 34, 27, 36, 30, 23, 5, 16, 1, 14, 9, 18, 7, 12, 3 | 1 to 1 | 1+1⁄18 to 1 | −$0.027 | 1+1⁄9 to 1 | −$0.053 |

| Black | 15, 4, 2, 17, 6, 13, 11, 8, 10, 24, 33, 20, 31, 22, 29, 28, 35, 26 | 1 to 1 | 1+1⁄18 to 1 | −$0.027 | 1+1⁄9 to 1 | −$0.053 |

| 1 to 18 | 1, 2, 3, ..., 18 | 1 to 1 | 1+1⁄18 to 1 | −$0.027 | 1+1⁄9 to 1 | −$0.053 |

| 19 to 36 | 19, 20, 21, ..., 36 | 1 to 1 | 1+1⁄18 to 1 | −$0.027 | 1+1⁄9 to 1 | −$0.053 |

Top line (0, 00, 1, 2, 3) has a different expected value because of approximation of the correct 6+1⁄5-to-1 payout obtained by the formula to 6-to-1.

If en prison rules are used, the house edge on the 1:1 bets is reduced to 1.35%-1.38% on a single-zero wheel,[10] and to 2.63% on a double-zero wheel.[11]

House edge

[edit]The house average or house edge or house advantage (also called the expected value) is the amount the player loses relative to any bet made, on average. If a player bets on a single number in the American game there is a probability of 1⁄38 that the player wins 35 times the bet, and a 37⁄38 chance that the player loses their bet. The expected value is:

- −1 × 37⁄38 + 35 × 1⁄38 = −0.0526 (5.26% house edge)

For European roulette, a single number wins 1⁄37 and loses 36⁄37:

- −1 × 36⁄37 + 35 × 1⁄37 = −0.0270 (2.70% house edge)

For triple-zero wheels, a single number wins 1⁄39 and loses 38⁄39:

- −1 × 38⁄39 + 35 × 1⁄39 = −0.0769 (7.69% house edge)

Mathematical model

[edit]As an example, the European roulette model, that is, roulette with only one zero, can be examined. Since this roulette has 37 cells with equal odds of hitting, this is a final model of field probability , where , for all .

Call the bet a triple , where is the set of chosen numbers, is the size of the bet, and determines the return of the bet.[12]

The rules of European roulette have 10 types of bets. First the 'Straight Up' bet can be imagined. In this case, , for some , and is determined by

The bet's expected net return, or profitability, is equal to

Without details, for a bet, black (or red), the rule is determined as

and the profitability

- .

For similar reasons it is simple to see that the profitability is also equal for all remaining types of bets. .[13]

In reality this means that, the more bets a player makes, the more they are going to lose independent of the strategies (combinations of bet types or size of bets) that they employ:

Here, the profit margin for the roulette owner is equal to approximately 2.7%. Nevertheless, several roulette strategy systems have been developed despite the losing odds. These systems can not change the odds of the game in favor of the player.

The odds for the player in American roulette are even worse, as the bet profitability is at worst , and never better than .[citation needed]

Simplified mathematical model

[edit]For a roulette wheel with green numbers and 36 other unique numbers, the chance of the ball landing on a given number is . For a betting option with numbers defining a win, the chance of winning a bet is

For example, if a player bets on red, there are 18 red numbers, , so the chance of winning is .

The payout given by the casino for a win is based on the roulette wheel having 36 outcomes, and the payout for a bet is given by .

For example, betting on 1-12 there are 12 numbers that define a win, , the payout is , so the bettor wins 3 times their bet.

The average return on a player's bet is given by

For , the average return is always lower than 1, so on average a player will lose money.

With 1 green number, , the average return is , that is, after a bet the player will on average have of their original bet returned to them. With 2 green numbers, , the average return is . With 3 green numbers, , the average return is .

This shows that the expected return is independent of the choice of bet.

Called (or call) bets or announced bets

[edit]

Although most often named "call bets" technically these bets are more accurately referred to as "announced bets". The legal distinction between a "call bet" and an "announced bet" is that a "call bet" is a bet called by the player without placing any money on the table to cover the cost of the bet. In many jurisdictions (most notably the United Kingdom) this is considered gambling on credit and is illegal. An "announced bet" is a bet called by the player for which they immediately place enough money to cover the amount of the bet on the table, prior to the outcome of the spin or hand in progress being known.

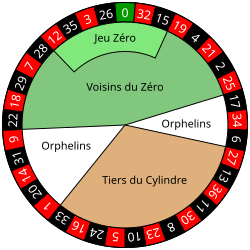

There are different number series in roulette that have special names attached to them. Most commonly these bets are known as "the French bets" and each covers a section of the wheel. For the sake of accuracy, zero spiel, although explained below, is not a French bet, it is more accurately "the German bet". Players at a table may bet a set amount per series (or multiples of that amount). The series are based on the way certain numbers lie next to each other on the roulette wheel. Not all casinos offer these bets, and some may offer additional bets or variations on these.

Voisins du zéro (neighbors of zero)

[edit]This is a name, more accurately "grands voisins du zéro", for the 17 numbers that lie between 22 and 25 on the wheel, including 22 and 25 themselves. The series is 22-18-29-7-28-12-35-3-26-0-32-15-19-4-21-2-25 (on a single-zero wheel).

Nine chips or multiples thereof are bet. Two chips are placed on the 0-2-3 trio; one on the 4–7 split; one on 12–15; one on 18–21; one on 19–22; two on the 25-26-28-29 corner; and one on 32–35.

Jeu zéro (zero game)

[edit]Zero game, also known as zero spiel (Spiel is German for game or play), is the name for the numbers closest to zero. All numbers in the zero game are included in the voisins, but are placed differently. The numbers bet on are 12-35-3-26-0-32-15.

The bet consists of four chips or multiples thereof. Three chips are bet on splits and one chip straight-up: one chip on 0–3 split, one on 12–15 split, one on 32–35 split and one straight-up on number 26.

This type of bet is popular in Germany and many European casinos. It is also offered as a 5-chip bet in many Eastern European casinos. As a 5-chip bet, it is known as "zero spiel naca" and includes, in addition to the chips placed as noted above, a straight-up on number 19.

Le tiers du cylindre (third of the wheel)

[edit]This is the name for the 12 numbers that lie on the opposite side of the wheel between 27 and 33, including 27 and 33 themselves. On a single-zero wheel, the series is 27-13-36-11-30-8-23-10-5-24-16-33. The full name (although very rarely used, most players refer to it as "tiers") for this bet is "le tiers du cylindre" (translated from French into English meaning one third of the wheel) because it covers 12 numbers (placed as 6 splits), which is as close to 1⁄3 of the wheel as one can get.

Very popular in British casinos, tiers bets outnumber voisins and orphelins bets by a massive margin.

Six chips or multiples thereof are bet. One chip is placed on each of the following splits: 5–8, 10–11, 13–16, 23–24, 27–30, and 33–36.

The tiers bet is also called the "small series" and in some casinos (most notably in South Africa) "series 5-8".

A variant known as "tiers 5-8-10-11" has an additional chip placed straight up on 5, 8, 10, and 11 and so is a 10-piece bet. In some places the variant is called "gioco Ferrari" with a straight up on 8, 11, 23 and 30, the bet is marked with a red G on the racetrack.

Orphelins (orphans)

[edit]These numbers make up the two slices of the wheel outside the tiers and voisins. They contain a total of 8 numbers, comprising 17-34-6 and 1-20-14-31-9.

Five chips or multiples thereof are bet on four splits and a straight-up: one chip is placed straight-up on 1 and one chip on each of the splits: 6–9, 14–17, 17–20, and 31–34.

... and the neighbors

[edit]A number may be backed along with the two numbers on either side of it in a 5-chip bet. For example, "0 and the neighbors" is a 5-chip bet with one piece straight-up on 3, 26, 0, 32, and 15. Neighbors bets are often put on in combinations, for example "1, 9, 14, and the neighbors" is a 15-chip bet covering 18, 22, 33, 16 with one chip, 9, 31, 20, 1 with two chips and 14 with three chips.

Any of the above bets may be combined; e.g. "orphelins by 1 and zero and the neighbors by 1". The "...and the neighbors" is often assumed by the croupier.

Final bets

[edit]Another bet offered on the single-zero game is "final", "finale", or "finals".

Final 4, for example, is a 4-chip bet and consists of one chip placed on each of the numbers ending in 4, that is 4, 14, 24, and 34. Final 7 is a 3-chip bet, one chip each on 7, 17, and 27. Final bets from final 0 (zero) to final 6 cost four chips. Final bets 7, 8 and 9 cost three chips.

Some casinos also offer split-final bets, for example final 5-8 would be a 4-chip bet, one chip each on the splits 5–8, 15–18, 25–28, and one on 35.

Full completes/maximums

[edit]A complete bet places all of the inside bets on a certain number. Full complete bets are most often bet by high rollers as maximum bets.

The maximum amount allowed to be wagered on a single bet in European roulette is based on a progressive betting model. If the casino allows a maximum bet of $1,000 on a 35-to-1 straight-up, then on each 17-to-1 split connected to that straight-up, $2,000 may be wagered. Each 8-to-1 corner that covers four numbers) may have $4,000 wagered on it. Each 11-to-1 street that covers three numbers may have $3,000 wagered on it. Each 5-to-1 six-line may have $6,000 wagered on it. Each $1,000 incremental bet would be represented by a marker that is used to specifically identify the player and the amount bet.

For instance, if a patron wished to place a full complete bet on 17, the player would call "17 to the maximum". This bet would require a total of 40 chips, or $40,000. To manually place the same wager, the player would need to bet:

| Bet type | Number(s) bet on | Chips | Amount waged |

|---|---|---|---|

| Straight-up | 17 | 1 | $1,000 |

| Split | 14-17 | 2 | $2,000 |

| Split | 16-17 | 2 | $2,000 |

| Split | 17-18 | 2 | $2,000 |

| Split | 17-20 | 2 | $2,000 |

| Street | 16-17-18 | 3 | $3,000 |

| Corner | 13-14-16-17 | 4 | $4,000 |

| Corner | 14-15-17-18 | 4 | $4,000 |

| Corner | 16-17-19-20 | 4 | $4,000 |

| Corner | 17-18-20-21 | 4 | $4,000 |

| Six line | 13-14-15-16-17-18 | 6 | $6,000 |

| Six line | 16-17-18-19-20-21 | 6 | $6,000 |

| Total | 40 | $40,000 |

The player calls their bet to the croupier (most often after the ball has been spun) and places enough chips to cover the bet on the table within reach of the croupier. The croupier will immediately announce the bet (repeat what the player has just said), ensure that the correct monetary amount has been given while simultaneously placing a matching marker on the number on the table and the amount wagered.

The payout for this bet if the chosen number wins is 392 chips, in the case of a $1000 straight-up maximum, $40,000 bet, a payout of $392,000. The player's wagered 40 chips, as with all winning bets in roulette, are still their property and in the absence of a request to the contrary are left up to possibly win again on the next spin.

Based on the location of the numbers on the layout, the number of chips required to "complete" a number can be determined.

- Zero costs 17 chips to complete and pays 235 chips.

- Number 1 and number 3 each cost 27 chips and pay 297 chips.

- Number 2 is a 36-chip bet and pays 396 chips.

- 1st column numbers 4 to 31 and 3rd column numbers 6 to 33, cost 30 chips each to complete. The payout for a win on these 30-chip bets is 294 chips.

- 2nd column numbers 5 to 32 cost 40 chips each to complete. The payout for a win on these numbers is 392 chips.

- Numbers 34 and 36 each cost 18 chips and pay 198 chips.

- Number 35 is a 24-chip bet which pays 264 chips.

Most typically (Mayfair casinos in London and other top-class European casinos) with these maximum or full complete bets, nothing (except the aforementioned maximum button) is ever placed on the layout even in the case of a win. Experienced gaming staff, and the type of customers playing such bets, are fully aware of the payouts and so the croupier simply makes up the correct payout, announces its value to the table inspector (floor person in the U.S.) and the customer, and then passes it to the customer, but only after a verbal authorization from the inspector has been received.

Also typically at this level of play (house rules allowing) the experienced croupier caters to the needs of the customer and will most often add the customer's winning bet to the payout, as the type of player playing these bets very rarely bets the same number two spins in succession. For example, the winning 40-chip / $40,000 bet on "17 to the maximum" pays 392 chips / $392,000. The experienced croupier would pay the player 432 chips / $432,000, that is 392 + 40, with the announcement that the payout "is with your bet down".

There are also several methods to determine the payout when a number adjacent to a chosen number is the winner, for example, player bets "23 full complete" and number 26 is the winning number. The most notable method is known as the "station" method. When paying in stations, the dealer counts the number of ways or stations that the winning number hits the complete bet. In the example above, 26 hits 4 stations - 2 different corners, 1 split and 1 six-line. The dealer takes the number 4, multiplies it by 36, making 144 with the players bet down.

In some casinos, a player may bet full complete for less than the table straight-up maximum, for example, "number 17 full complete by $25" would cost $1000, that is 40 chips each at $25 value.

Betting strategies and tactics

[edit]Over the years, many people have tried to beat the casino, and turn roulette—a game designed to turn a profit for the house—into one on which the player expects to win. Most of the time this comes down to the use of betting systems, strategies which say that the house edge can be beaten by simply employing a special pattern of bets, often relying on the "Gambler's fallacy", the idea that past results are any guide to the future (for example, if a roulette wheel has come up 10 times in a row on red, that red on the next spin is any more or less likely than if the last spin was black).

All betting systems that rely on patterns, when employed on casino edge games will result, on average, in the player losing money.[14] In practice, players employing betting systems may win, and may indeed win very large sums of money, but the losses (which, depending on the design of the betting system, may occur quite rarely) will outweigh the wins. Certain systems, such as the Martingale, described below, are extremely risky, because the worst-case scenario (which is mathematically certain to happen, at some point) may see the player chasing losses with ever-bigger bets until they run out of money.

The American mathematician Patrick Billingsley said[15][unreliable source?] that no betting system can convert a subfair game into a profitable enterprise. At least in the 1930s, some professional gamblers were able to consistently gain an edge in roulette by seeking out rigged wheels (not difficult to find at that time) and betting opposite the largest bets.

Prediction methods

[edit]Whereas betting systems are essentially an attempt to beat the fact that a geometric series with initial value of 0.95 (American roulette) or 0.97 (European roulette) will inevitably over time tend to zero,[16] engineers instead attempt to overcome the house edge through predicting the mechanical performance of the wheel, most notably by Joseph Jagger at Monte Carlo in 1873. These schemes work by determining that the ball is more likely to fall at certain numbers. If effective, they raise the return of the game above 100%, defeating the betting system problem.

Edward O. Thorp (the developer of card counting and an early hedge-fund pioneer) and Claude Shannon (a mathematician and electronic engineer best known for his contributions to information theory) built the first wearable computer to predict the landing of the ball in 1961. This system worked by timing the ball and wheel, and using the information obtained to calculate the most likely octant where the ball would fall. Ironically, this technique works best with an unbiased wheel though it could still be countered quite easily by simply closing the table for betting before beginning the spin.

In 1982, several casinos in Britain began to lose large sums of money at their roulette tables to teams of gamblers from the US. Upon investigation by the police, it was discovered they were using a legal system of biased wheel-section betting. As a result of this, the British roulette wheel manufacturer John Huxley manufactured a roulette wheel to counteract the problem.

The new wheel, designed by George Melas, was called "low profile" because the pockets had been drastically reduced in depth, and various other design modifications caused the ball to descend in a gradual approach to the pocket area. In 1986, when a professional gambling team headed by Billy Walters won $3.8 million using the system on an old wheel at the Golden Nugget in Atlantic City, every casino in the world took notice, and within one year had switched to the new low-profile wheel.

Thomas Bass, in his book The Eudaemonic Pie (1985) (published as The Newtonian Casino in Britain), has claimed to be able to predict wheel performance in real time. The book describes the exploits of a group of University of California Santa Cruz students, who called themselves the Eudaemons, who in the late 1970s used computers in their shoes to win at roulette. This is an updated and improved version of Edward O. Thorp's approach, where Newtonian laws of motion are applied to track the roulette ball's deceleration; hence the British title.

To defend against exploits like these, many casinos use tracking software, use wheels with new designs, rotate wheel heads, and randomly rotate pocket rings.[17]

At the Ritz London casino in March 2004, two Serbs and a Hungarian used a laser scanner hidden inside a mobile phone linked to a computer to predict the sector of the wheel where the ball was most likely to drop. They netted £1.3m in two nights.[18] They were arrested and kept on police bail for nine months, but eventually released and allowed to keep their winnings as they had not interfered with the casino equipment.[19]

Specific betting systems

[edit]The numerous even-money bets in roulette have inspired many players over the years to attempt to beat the game by using one or more variations of a martingale betting strategy, wherein the gambler doubles the bet after every loss, so that the first win would recover all previous losses, plus win a profit equal to the original bet. The problem with this strategy is that, remembering that past results do not affect the future, it is possible for the player to lose so many times in a row, that the player, doubling and redoubling their bets, either runs out of money or hits the table limit. A large financial loss is almost certain in the long term if the player continues to employ this strategy. Another strategy is the Fibonacci system, where bets are calculated according to the Fibonacci sequence. Regardless of the specific progression, no such strategy can statistically overcome the casino's advantage, since the expected value of each allowed bet is negative.

Types of betting system

[edit]Betting systems in roulette can be divided in to two main categories:

Negative progression systems involve increasing the size of one's bet when they lose. This is the most common type of betting system. The goal of this system is to recoup losses faster so that one can return to a winning position more quickly after a losing streak. The typical shape of these systems is small but consistent wins followed by occasional catastrophic losses. Examples of negative progression systems include the Martingale system, the Fibonacci system, the Labouchère system, and the d'Alembert system.

Positive progression systems involve increasing the size of one's bet when one wins. The goal of these systems is to either exacerbate the effects of winning streaks (e.g. the Paroli system) or to take advantage of changes in luck to recover more quickly from previous losses (e.g. Oscar's grind). The shape of these systems is typically small but consistent losses followed by occasional big wins. However, over the long run these wins do not compensate for the losses incurred in between.[20]

Reverse Martingale system

[edit]The Reverse Martingale system, also known as the Paroli system, follows the idea of the martingale betting strategy, but reversed. Instead of doubling a bet after a loss the gambler doubles the bet after every win. The system creates a false feeling of eliminating the risk of betting more when losing, but, in reality, it has the same problem as the martingale strategy. By doubling bets after every win, one keeps betting everything they have won until they either stop playing, or lose it all.

Labouchère system

[edit]The Labouchère System is a progression betting strategy like the martingale but does not require the gambler to risk their stake as quickly with dramatic double-ups. The Labouchere System involves using a series of numbers in a line to determine the bet amount, following a win or a loss. Typically, the player adds the numbers at the front and end of the line to determine the size of the next bet. If the player wins, they cross out numbers and continue working on the smaller line. If the player loses, then they add their previous bet to the end of the line and continue to work on the longer line. This is a much more flexible progression betting system and there is much room for the player to design their initial line to their own playing preference.

This system is one that is designed so that when the player has won over a third of their bets (less than the expected 18/38), they will win. Whereas the martingale will cause ruin in the event of a long sequence of successive losses, the Labouchère system will cause bet size to grow quickly even where a losing sequence is broken by wins. This occurs because as the player loses, the average bet size in the line increases.

As with all other betting systems, the average value of this system is negative.

D'Alembert system

[edit]The system, also called montant et demontant (from French, meaning upwards and downwards), is often called a pyramid system. It is based on a mathematical equilibrium theory devised by a French mathematician of the same name. Like the martingale, this system is mainly applied to the even-money outside bets, and is favored by players who want to keep the amount of their bets and losses to a minimum. The betting progression is very simple: After each loss, one unit is added to the next bet, and after each win, one unit is deducted from the next bet. Starting with an initial bet of, say, 1 unit, a loss would raise the next bet to 2 units. If this is followed by a win, the next bet would be 1 units.

This betting system relies on the gambler's fallacy—that the player is more likely to lose following a win, and more likely to win following a loss.

Other systems

[edit]There are numerous other betting systems that rely on this fallacy, or that attempt to follow 'streaks' (looking for patterns in randomness), varying bet size accordingly.

Many betting systems are sold online and purport to enable the player to 'beat' the odds. One such system was advertised by Jason Gillon of Rotherham, UK, who claimed one could 'earn £200 daily' by following his betting system, described as a 'loophole'. As the system was advertised in the UK press, it was subject to Advertising Standards Authority regulation, and following a complaint, it was ruled by the ASA that Mr. Gillon had failed to support his claims, and that he had failed to show that there was any loophole.

Notable winnings

[edit]- In the 1960s and early 1970s, Richard Jarecki won about $1.2 million at dozens of European casinos. He claimed that he was using a mathematical system designed on a powerful computer. In reality, he simply observed more than 10,000 spins of each roulette wheel to determine flaws in the wheels. Eventually the casinos realized that flaws in the wheels could be exploited, and replaced older wheels. The manufacture of roulette wheels has improved over time.[21]

- In 1963 Sean Connery, filming From Russia with Love in Italy, attended the casino in Saint-Vincent and won three consecutive times on the number 17, his winnings riding on the second and third spins.[22]

- In the early 1990s, Gonzalo García-Pelayo performed computer analysis on many roulette spins at the Casino de Madrid in Madrid, Spain, winning 600,000 euros in a single day, and two million euros in total. Legal action against him by the casino was unsuccessful, it being ruled that the casino should fix its wheel.[23][24]

- In 2004, Ashley Revell of London sold all of his possessions, clothing included, and placed his entire net worth of US$135,300 on red at the Plaza Hotel in Las Vegas. The ball landed on "Red 7" and Revell walked away with $270,600.[25]

See also

[edit]- Bauernroulette

- Boule

- Eudaemons

- Monte Carlo Paradox

- Russian roulette

- Straperlo

- The Gambler, a novel written by Fyodor Dostoevsky inspired by his addiction to roulette

- Le multicolore; a game similar to roulette

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Blaise Pascal". Lemelson-MIT. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- ^ Epstein, Richard A. (2009). The theory of gambling and statistical logic (2nd ed.). London: Academic. ISBN 978-0-12-374940-6.

- ^ "Article The Game of EO in The Sporting Magazine, February 1793, pages 274-275". 1792.

- ^ Roulette Wheel Study, Ron Shelley, (1988)

- ^ Trumps (September 2010). The Modern Pocket Hoyle: Containing All The Games Of Skill And Chance As Played In This Country At The Present Time (1868). Kessinger. p. 220. ISBN 978-1167231667.

- ^ Doak, Melissa J. (2011). Gambling : what's at stake? (2011 ed.). Detroit, Mich.: Gale. p. 114. ISBN 978-1414448619.

- ^ "California Roulette and California Craps as House-Banked Card Games" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ^ "Predicting the outcome of roulette". ResearchGate. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- ^ Scarne, John (1986). Scarne's new complete guide to gambling (Fully rev., expanded, updated ed.). New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 403. ISBN 0-671-63063-6.

- ^ Shackleford, Michael. "Roulette -- The Basics". wizardofodds.com. Retrieved 22 February 2025.

- ^ Grochowski, John (13 March 2023). "Can 00 roulette top single-zero? It depends on the half-back rule". Atlantic City Weekly. Retrieved 22 February 2025.

- ^ Barboianu, Catalin (2008). Roulette Odds and Profits: The Mathematics of Complex Bets. Infarom. p. 23. ISBN 9789738752078.

- ^ Roulette Math, en.wikibooks.org

- ^ "The Truth about Betting Systems". wizardofodds.com. 15 June 2019. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- ^ Billingsley, Patrick (1986). Probability and Measure (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons Inc. p. 94. ISBN 9780471804789.

- ^ Small, Michael; Tse, Chi Kong (September 2012). "Predicting the outcome of roulette". Chaos (Woodbury, N.Y.). 22 (3): 033150. arXiv:1204.6412. Bibcode:2012Chaos..22c3150S. doi:10.1063/1.4753920. ISSN 1089-7682. PMID 23020489.

- ^ Zender, Bill (2006). Advantage Play for the Casino Executive.

- ^ The sting: did gang really use a laser, phone and a computer to take the Ritz for £1.3m? | Science | The Guardian, guardian.co.uk

- ^ du Sautoy, Marcus (2011). The number mysteries : a mathematical odyssey through everyday life (1st Palgrave Macmillan ed.). New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 237. ISBN 978-0230113848.

- ^ "Roulette Systems". roulettestar.com. Retrieved 26 February 2021.

- ^ Slotnik, Daniel L. (12 August 2018). "Richard Jarecki, Doctor Who Conquered Roulette, Dies at 86". The New York Times.

- ^ The complete illustrated guide to gambling by Alan Wykes, Doubleday, 1964, pp 226, 227. . Internet Archive (a free registration req.) > [1]

- ^ "Theage.com.au". 24 June 2004.

- ^ Wheel of Fortune | Motley Fool, fool.com

- ^ "'All or nothing' gamble succeeds". BBC. 12 April 2004. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

External links

[edit]Roulette

View on GrokipediaHistory

Origins in Europe

A common but debunked myth attributes the origins of roulette to the French mathematician Blaise Pascal in the 17th century, stemming from his experiments with perpetual motion machines. However, no historical evidence supports this claim, and roulette emerged in 18th-century France as a combination of earlier wheel-based games.[1][2] Roulette's development in Europe drew significant influence from earlier wheel-based games prevalent in 17th- and 18th-century France and Britain, such as Roly-Poly and Even-Odd. Roly-Poly, documented as early as the 1720s, involved a wheel with sections for even and odd outcomes plus a central "bank" pocket that favored the house, while Even-Odd simplified betting to parity with similar mechanics; these games introduced the concept of a spinning wheel and ball for random outcomes, blending with Italian lotteries like Biribi to form roulette's hybrid structure. The innovation of zero pockets created a house edge by ensuring not all bets paid even money, transforming informal pastimes into structured gambling. Early European wheels included both single zero (0) and double zero (00), with the single-zero configuration introduced later in 1843.[4][5][6] The first recorded appearances of roulette in French casinos occurred in the mid- to late 18th century, with primitive wheels used in illicit gaming houses despite periodic bans, and the first documented wheel appearing around 1796. By the late 18th century, the game gained formal traction in Paris, with official rules codified around 1796 at establishments in the Palais Royal, including standardized betting options and the wheel layout that evolved into modern variants. This period solidified roulette's place in French high society, where it was played in salons and early casinos, blending chance with elegance before spreading further across the continent.[7][8][4]Evolution and Spread

Following its emergence in 18th-century French salons, roulette began to evolve and spread across Europe in the mid-19th century. In 1843, brothers François and Louis Blanc introduced a single-zero roulette wheel at the casino in Bad Homburg, Germany, removing the double zero to offer better odds to players and attract gamblers away from competing establishments in Paris.[9] This innovation helped popularize the game in German spa towns, where it became a staple of upscale entertainment.[4] The Blanc brothers further propelled roulette's dissemination when gambling was banned in Germany in the 1860s, leading them to relocate to Monte Carlo, Monaco, in 1863. There, they took over the struggling Casino de Monte-Carlo and implemented the single-zero variant, which boosted the casino's fortunes and established European roulette as the dominant form on the continent.[10] Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, French immigrants brought an earlier double-zero version of the game to New Orleans in the early 19th century, where it thrived in the city's vibrant gambling scene along the Mississippi River.[11] This adaptation, known as American roulette, incorporated the additional double zero to increase the house edge, distinguishing it from the European style and solidifying its place in U.S. gaming culture.[12] In the United States, roulette's growth faced setbacks from anti-gambling laws, such as New York's 1908 Hart-Agnew Law, which effectively shut down legal betting venues and race tracks, pushing the game underground or westward toward more permissive regions.[13] The tide turned in 1931 when Nevada legalized casino gambling to revive its economy during the Great Depression, sparking the development of Las Vegas as a gaming hub where roulette quickly became a centerpiece of casino floors.[14] Post-World War II economic prosperity fueled a global casino boom, with roulette spreading to new legalized markets in Europe, Asia, and beyond as international tourism and resort construction proliferated.Modern Variations

The advent of online roulette in the late 1990s marked a significant digital transformation of the game, driven by the proliferation of internet access and the development of random number generator (RNG) software to simulate wheel spins fairly and independently.[4] Early online casinos, such as those launched around 1996, integrated RNG technology to ensure unbiased outcomes, replicating the randomness of physical wheels while allowing players to access the game from personal computers.[15] This innovation expanded roulette's reach beyond land-based venues, with RNG-based versions becoming a staple in virtual casinos by the early 2000s, offering variants like European and American styles with certified fairness through independent audits.[16] Building on this foundation, live dealer roulette emerged in the early to mid-2000s, introducing real-time video streams of professional dealers operating physical wheels to bridge the gap between online convenience and traditional casino immersion.[17] Pioneered by providers like Playtech and Evolution Gaming, these formats utilized broadband internet and webcam technology, allowing players to interact via chat while watching spins from studios in locations such as Latvia and the Philippines.[18] By the late 2000s, live dealer streams had evolved to include multiple camera angles and high-definition video, enhancing player trust and engagement in online platforms.[19] In parallel, modern casinos have introduced compact variants like mini-roulette, which features a wheel with only 13 pockets—numbers 1 through 12 plus a single zero—to accelerate gameplay and appeal to casual players seeking quicker sessions.[20] This version maintains core betting mechanics but adjusts payouts proportionally, such as 11:1 for straight-up bets, and has gained popularity in both land-based and online settings since its development in the early 2000s.[21] Complementing this, multi-wheel roulette variants, such as those with up to eight synchronized wheels, enable simultaneous spins to increase betting volume and excitement, often featured in live dealer formats launched by Evolution Gaming in 2020.[22] These adaptations, including Instant Roulette with 12 auto-spinning wheels, cater to high-volume players while preserving the game's probabilistic integrity.[23] Regulatory frameworks for roulette and online gambling have intensified in the 2020s, with the European Union emphasizing responsible gambling features on platforms to mitigate addiction risks through mandatory tools like deposit limits, self-exclusion options, and behavioral monitoring.[24] EU member states, under directives like the Audiovisual Media Services Directive, require operators to implement age verification and reality checks, with the European Gaming and Betting Association advocating for standardized markers of harm detection in games including roulette.[25] In the United States, the 2018 repeal of the Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act (PASPA) indirectly spurred state-specific expansions of online casino gambling, legalizing real-money roulette in seven states—Connecticut, Delaware, Michigan, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and West Virginia—by 2025, each with tailored rules on licensing, taxation, and player protections.[26] These developments reflect a patchwork of regulations, where states like New Jersey, which launched iGaming in 2013 and expanded post-PASPA, impose geofencing and responsible gaming mandates similar to EU standards.[27] Emerging technologies have further innovated roulette through virtual reality (VR) pilots in casino apps from 2023 to 2025, creating immersive 3D environments where players use VR headsets to interact at virtual tables, spin wheels, and socialize in simulated casinos.[28] Platforms like SlotsMillion and PokerStars VR have integrated VR roulette, allowing avatar-based play with realistic physics and multi-player features, tested in beta releases to enhance engagement while incorporating responsible gambling safeguards.[29] These pilots, often powered by Unity or Oculus software, represent early adoption in regulated markets, with projections for broader integration by 2026 to blend physical and digital experiences.[30]Equipment and Setup

Roulette Wheel Design

The roulette wheel is a precision-engineered device central to the game, consisting of a rotating bowl with numbered pockets designed to ensure fair and random outcomes through balanced construction and uniform components. Traditional wheels feature a wooden or composite bowl that holds the pockets, separated by frets, with a central spindle allowing smooth rotation. Modern designs prioritize durability, resistance to wear, and compliance with gaming regulations to prevent bias.[31] Standard roulette wheels in professional casino settings measure approximately 32 inches in diameter, accommodating either the European single-zero configuration with 37 pockets (numbered 0 through 36) or the American double-zero version with 38 pockets (numbered 0, 00 through 36). The European wheel's pockets alternate between red and black numbers, with the green 0, while the American includes an additional green 00, increasing the house edge. These sizes ensure consistent ball trajectories and are scaled for casino environments, with smaller variants (18-30 inches) used for non-professional play.[32][33] The bowl is typically crafted from high-grade hardwoods like mahogany for aesthetic appeal and stability, though contemporary wheels often use fiberglass-reinforced plastic to enhance longevity and reduce maintenance. Frets, the metal dividers (commonly brass, aluminum, or chrome-plated for non-magnetic properties) between pockets, are scalloped to deflect and slow the ball, promoting randomness by interrupting its spin. Roulette balls, once made from ivory for their smooth roll and rebound, have transitioned to synthetic materials such as Teflon, nylon, or phenolic resin since the mid-20th century to address ethical concerns over elephant ivory and improve fairness through consistent density and reduced wear on the wheel.[34][31][35] To facilitate the ball's path, the wheel incorporates a slight incline in the upper ball track, guiding the ball counterclockwise while the wheel rotates clockwise, eventually causing it to drop into a pocket. Pockets are uniformly dimensioned, elliptically shaped with consistent depth, to capture the ball unpredictably without favoring specific numbers. At least eight non-metallic canoe stops along the track further deflect the ball. Manufacturing adheres to strict standards, including perfect horizontal leveling of the rotor to eliminate bias, secure non-moving parts, and overall non-metallic construction where possible to avoid magnetic interference. Wheels are certified by independent labs such as Gaming Laboratories International (GLI) for uniformity, balance, and tamper resistance, with each unit featuring a unique manufacturer identifier for traceability.[36][37]Table Layout and Components

The roulette table is covered with a standard green baize cloth that forms the primary betting surface, featuring a numbered grid of 1 through 36 arranged in three columns of 12 numbers each, dedicated sections for the zero pocket (in European variants) or double zero (in American variants), and surrounding areas for outside bets including red/black, odd/even, and high/low options.[38] This layout ensures clear separation between inside bets on specific numbers and outside bets on broader categories, with the cloth typically made from durable wool or synthetic felt to withstand repeated use.[39] At the dealer's position, opposite the players' side, the table includes chip racks—such as multi-level holders like the Chipper Champ—for organizing and dispensing casino chips and value chips, along with space for managing the overall layout to accommodate both inside and outside bet placements.[39] A marker known as a dolly, often a small plastic or metal indicator, is positioned by the dealer on the layout to denote the winning number after the ball comes to rest on the adjacent wheel.[39] Key accessories facilitate smooth gameplay, including a rake—a telescoping tool with an acrylic head used by the dealer to sweep away losing bets and chips from the layout—and the aforementioned dolly for result marking; in electronic versions adapted for online play, these elements are digitized, with virtual rakes and markers simulated on interactive screens and player terminals to replicate the physical experience.[40] Roulette tables typically measure 8 feet by 4 feet to provide sufficient space for up to seven players and the dealer, though some casinos employ multi-game tables or electronic stadium setups that incorporate roulette alongside other games like blackjack or baccarat for efficient floor space utilization.[41][42]Number Sequence and Pocket Arrangement

The roulette wheel's number sequence is a deliberate arrangement of 37 pockets in the European version (or 38 in the American), designed to promote randomness and fairness by distributing numbers in a non-sequential order around the circumference. This fixed order ensures that adjacent numbers do not follow numerical progression, instead alternating colors and balancing other attributes to prevent exploitable patterns. The sequence begins with the green zero pocket and proceeds counterclockwise. In European roulette, the standard sequence is: 0, 32, 15, 19, 4, 21, 2, 25, 17, 34, 6, 27, 13, 36, 11, 30, 8, 23, 10, 5, 24, 16, 33, 1, 20, 14, 31, 9, 22, 18, 29, 7, 28, 12, 35, 3, 26.[38] Pockets for numbers 1 through 10 and 19 through 28 are colored red, while 11 through 18 and 29 through 36 are black, creating a strict alternation of red and black around the wheel except for the green 0.[43] Odd and even numbers are distributed such that no more than two of the same parity are adjacent, typically alternating in pairs (e.g., two odds followed by two evens).[44] Similarly, low numbers (1-18) and high numbers (19-36) are interspersed evenly, with roughly equal representation in any given sector, to balance outside bets like red/black, odd/even, and high/low.[43] The green 0 stands ungrouped from these categories, serving as the house advantage without aligning to red, black, odd, even, low, or high.[44] This arrangement originated in the 1840s when French brothers François and Louis Blanc redesigned the wheel for the Bad Homburg casino in Germany, introducing the single-zero version to reduce the house edge from the prior double-zero setup and enhance player appeal.[45] The non-sequential placement specifically aims to eliminate sector bias, where physical imperfections in early wheels could favor clustered numbers; by scattering similar attributes (e.g., all reds or highs), the design makes it difficult to predict or exploit gravitational or manufacturing flaws over short sessions.[44][46] The American roulette wheel modifies this by adding a second green pocket for 00, increasing the total to 38 and raising the house edge to 5.26% on most bets.[43] The sequence starts from 0 and runs counterclockwise: 0, 28, 9, 26, 30, 11, 7, 20, 32, 17, 5, 22, 34, 15, 3, 24, 36, 13, 1, 00, 27, 10, 25, 29, 12, 8, 19, 31, 18, 6, 21, 33, 16, 4, 23, 35, 2, 14.[47] The 00 is positioned between 1 and 27, disrupting the European balance slightly by creating minor clusters (e.g., more consecutive evens in some sectors) and further scattering the color and parity alternations, though it retains the core principle of randomization.[48] This adaptation emerged in the United States in the 19th century, prioritizing higher casino advantage over the purer distribution of the European model.[45]Rules of Play

Basic Gameplay Mechanics

In a standard casino roulette game, players begin by purchasing color-coded chips from the dealer, with the chip value determined by the buy-in amount, typically divided across a set number of chips such as 100 for a full rack.[43] These chips are placed on the betting layout to wager on various outcomes before the dealer initiates the spin, adhering to table-specific minimum and maximum bet limits enforced to manage game pace and house exposure.[49] Players may place multiple bets simultaneously, but all wagers must be finalized prior to the dealer's announcement signaling the end of betting.[50] The dealer, known as the croupier, then spins the roulette wheel counterclockwise while releasing the ball clockwise along the outer track, ensuring the two elements rotate in opposite directions to promote randomness.[51] As the ball's momentum slows and it approaches the pockets, the dealer calls "no more bets" to halt any further chip placements or adjustments, preventing interference with the outcome.[52] This call typically occurs when the ball nears the wheel's deflection area, maintaining fairness and game integrity.[50] Once the ball settles into a numbered pocket, the dealer announces the winning number and its color, marking the result with a layout indicator such as a dolly.[43] Losing bets are immediately cleared and collected by the dealer, while winning bets remain on the layout for payout processing in accordance with standard procedures.[49] The dealer handles payouts methodically, starting from inside bets and moving outward, ensuring all eligible wagers are resolved before the next round begins.[43] For even-money bets (such as red/black or odd/even) on single-zero wheels, special rules apply if the ball lands on zero: under the en prison rule, the bet is "imprisoned" or held for the next spin, returned without winnings if it loses again, or released even if it wins; alternatively, the la partage rule allows players to recover half their stake immediately, with the other half lost.[43] These mechanisms, common in European and French roulette variants, mitigate the house advantage on such outcomes without altering the core spin resolution.[43] A typical roulette turn lasts 45 to 60 seconds from the start of betting to the completion of payouts, allowing for efficient play while accommodating multiple participants.[53] Casino etiquette dictates that players refrain from touching the layout or their chips after the "no more bets" call, respecting the dealer's control and avoiding disputes over wager alterations.[52] This practice, along with prompt bet placement, ensures smooth progression and communal enjoyment at the table.[54]Casino-Specific Rules

In casinos, roulette tables enforce specific bet placement limits to regulate wagering and maintain game flow. Minimum bets are typically set separately for inside bets (such as straight-up numbers or splits, where the total wager must meet or exceed the table minimum) and outside bets (such as red/black or odd/even, where each individual bet must meet the minimum). For instance, a common configuration features a $1 minimum for inside bets and $5 for outside bets, though these vary by casino and table stakes. Additionally, once the dealer spins the ball and announces "no more bets," players cannot place, change, or remove wagers, ensuring fairness during the outcome determination.[55][43] The outcome of the ball landing on zero (or double zero in American wheels) triggers distinct house rules, particularly for even-money outside bets. A straight-up bet on zero pays 35:1, matching the payout for any numbered pocket. However, even-money bets lose their full amount in standard American roulette if zero appears. In contrast, many European and French roulette variants apply mitigating rules: under "la partage," half the stake on even-money bets is returned when zero lands, while "en prison" holds the full bet for the next spin—if it wins, the original stake is returned without profit; if it loses or lands on zero again, the bet is forfeited. These rules are casino-specific and often displayed on the table layout.[43] Roulette employs color-coded, non-denominated chips unique to each player to prevent confusion during betting. Upon buying in, a player receives chips in one of several colors (e.g., white, red, blue), with the value per chip set by dividing the buy-in amount by the number of chips issued—commonly stacks of 20 chips, such as $20 buy-in yielding $1 per chip.[43] Casinos limit stacks to a maximum height, often equivalent to $100 in value (e.g., 20 chips at $5 each), to ensure visibility and quick resolution by the dealer. When cashing out, these chips are exchanged only at the roulette table for value chips or currency.[43][56] Dispute resolution in roulette relies on rigorous oversight to address issues like contested bet placements or payouts. Casinos deploy surveillance cameras covering all table angles, enabling instant video review by security or pit supervisors to verify actions. In certain venues, verbal calls by players for announced bets (e.g., "voisins du zero") are considered binding if confirmed by the dealer before the spin, though physical chip placement remains the primary evidence. Unresolved disputes may escalate to gaming commission protocols, prioritizing recorded footage for impartial adjudication.[57][58]Regional Variations

Roulette exhibits significant regional differences in rules and equipment, primarily to comply with local gambling laws and traditions, affecting the house edge and gameplay. American roulette features a wheel with both a single zero (0) and double zero (00), leading to 38 pockets and a house edge of 5.26% on nearly all bets; unlike European variants, it does not incorporate the en prison rule, where even-money bets can be held over for the next spin after a zero outcome.[43][59] In contrast, European and French roulette use a single-zero wheel with 37 pockets, yielding a standard house edge of 2.70%; French roulette specifically includes the la partage rule, which applies to even-money bets (such as red/black or odd/even) when the ball lands on zero, allowing players to recover half their stake and reducing the house edge on those bets to 1.35%.[60][61][62] United Kingdom casinos typically employ single-zero wheels similar to European roulette, where call bets—verbal announcements of complex wagers like tiers du cylindre covering specific wheel sections—are commonly permitted and placed by the dealer without physical chips on the table until resolved.[63][64] In California, state laws prohibit traditional roulette wheels, so the game is adapted using a standard deck of cards (often 37 or 38 cards numbered 0 to 36 or including 00) shuffled and drawn to determine outcomes, maintaining similar odds and payouts to wheel-based versions while complying with banking and house-banked game restrictions.[65][66][67]Betting Options

Inside Bets

Inside bets in roulette refer to wagers placed directly on specific numbers or small groups of adjacent numbers on the inner section of the betting table layout. These bets offer higher potential payouts compared to outside bets due to their lower probability of winning, as they target precise outcomes on the wheel.[68][69] The primary types of inside bets include the straight-up, split, street, corner, and six-line. A straight-up bet is placed on a single number, such as 17 or 32, and pays out at 35 to 1 if the ball lands on that number.[68][69] A split bet covers two adjacent numbers, either horizontally or vertically on the table, with a payout of 17 to 1.[68][69] The street bet (or row bet) involves three consecutive numbers in a horizontal row, offering an 11 to 1 payout.[68][69] A corner bet (also known as a square bet) targets four numbers forming a square at their intersection, with an 8 to 1 payout.[68][69] Finally, the six-line bet (or double street) covers six numbers across two adjacent rows, paying 5 to 1.[68][69] To illustrate, if a player places a $1 straight-up bet on the number 17 and the ball lands on it, the player receives $35 in winnings plus the original $1 stake returned, for a total of $36.[68][69] These bets emphasize the game's focus on individual wheel pockets, requiring precise placement on the table's numbered grid.| Bet Type | Description | Payout |

|---|---|---|

| Straight-Up | Single number | 35:1 |

| Split | Two adjacent numbers | 17:1 |

| Street | Three consecutive numbers in a row | 11:1 |

| Corner | Four numbers forming a square | 8:1 |

| Six-Line | Six numbers across two rows | 5:1 |

Outside Bets

Outside bets in roulette are wagers placed on the outer areas of the betting layout, covering larger groups of numbers rather than specific ones, and offering lower risk compared to inside bets. These bets are positioned outside the main number grid on the table, typically in designated boxes or at the ends of columns, and they exclude the zero (or double zero in American roulette), meaning a spin landing on zero results in a loss for all outside bets.[43] The most common outside bets include red/black and odd/even, each covering 18 numbers on a single-zero wheel with a 1:1 payout. A red/black bet is placed on the color boxes, wagering that the ball will land on a red or black number, while odd/even bets on the respective parity boxes cover all odd or even numbers from 1 to 36.[43][70] High/low bets, also known as manque/passe in French roulette, similarly offer 1:1 payouts and cover 18 numbers each: low (1-18) or high (19-36), placed in the corresponding boxes below the even-money color and parity options. Dozen bets cover 12 numbers in groups of 1-12 (first dozen), 13-24 (second), or 25-36 (third), with 2:1 payouts, and are placed in the three dedicated dozen boxes at the bottom of the layout. Column bets, paying 2:1, wager on one of the three vertical columns of 12 numbers each (e.g., numbers ending in 1, 4, 7, etc.), with chips placed in the spaces at the base of each column.[43][71] In some UK casinos, a non-standard variant called the snake bet covers 12 red numbers in a zigzag pattern across the layout—specifically 1, 5, 9, 12, 14, 16, 19, 23, 27, 30, 32, and 34—with a 2:1 payout, requiring placement of individual chips on each number to form the "snake" shape.[72][73]Announced Bets

Announced bets, also known as call bets or spoken bets, are a feature primarily in European and French roulette variants, where players verbally announce wagers on specific sectors of the roulette wheel rather than placing chips directly on the table layout for individual numbers. These bets cover groups of numbers based on their positions on the physical wheel, allowing for broader coverage without needing to place multiple chips on the betting cloth. They originated in French casinos and are typically available only at tables with a single zero wheel, as the announcements reference the wheel's sequence.[43] The most common announced bet is Voisins du Zéro (neighbors of zero), which covers 17 numbers clustered around the zero pocket on the wheel: 22, 18, 29, 7, 28, 12, 35, 3, 26, 0, 32, 15, 19, 4, 21, 2, and 25. This bet requires nine chips in total, placed as follows: 2 chips on the 0-2-3 trio, 1 chip each on the splits 4-7, 12-15, 18-21, 19-22, and 32-35, and 2 chips on the 25-26-28-29 corner. Payouts vary by the winning bet type, such as 35:1 for straights or 17:1 for splits.[43][74] Tiers du Cylindre (third of the wheel or cylinder) targets the 12 numbers opposite the zero sector on the wheel: 27, 13, 36, 11, 30, 8, 23, 10, 5, 24, 16, and 33. This bet uses six chips, all placed as split bets: 5-8, 10-11, 13-16, 23-24, 27-30, and 33-36. If any of these numbers wins, the payout is 17:1 per chip, effectively yielding a total return based on the single winning split. This bet covers approximately one-third of the wheel's non-zero numbers, providing balanced coverage away from the zero.[43] Orphelins (orphans) refers to the eight numbers on the wheel that are not included in either Voisins du Zéro or Tiers du Cylindre: 17, 34, 6, 1, 20, 14, 31, and 9. It requires five chips: one straight-up bet on 1 and four split bets on 6-9, 14-17, 17-20, and 31-34. Payouts are 35:1 for the straight-up on 1 or 17:1 for the splits, making it a cost-effective way to cover the remaining "unpaired" wheel sections. These numbers are positioned in two small arcs, one on each side of the wheel.[43] Jeu Zéro (zero game) is a smaller announced bet focusing on the seven numbers closest to zero: 12, 35, 3, 26, 0, 32, and 15. It uses four chips: three split bets on 0-3, 12-15, and 32-35, plus one straight-up on 26. This provides high concentration around zero with lower chip requirement, paying 35:1 on 26 or 17:1 on the splits if they win. It is often used as a quick, low-stake option in French roulette.[43] Finally, Neighbors bets allow flexibility by adding adjacent numbers to a base bet, typically covering a chosen number plus two on either side (five numbers total), though variations like five or nine neighbors exist. For example, neighbors of 17 would include 2, 25, 17, 34, and 6 (based on wheel sequence), placed as five straight-up chips. Each winning number pays 35:1, and the bet size scales with the number of neighbors selected, often announced with the count (e.g., "five neighbors of 17"). This customizable approach lets players extend coverage around any wheel position.[43]Odds and Payouts

Bet Odds Table

The following table provides a comprehensive summary of standard and announced bet types in roulette, detailing the bet name, numbers covered (including count for probability calculation), payout ratio, and winning probability for the European wheel (37 pockets, single zero). Payouts for announced bets vary based on the specific sub-bet that wins, as these are combinations of inside bets. Announced bets are primarily available on European or French roulette tables. For the American wheel (38 pockets, double zero), probabilities are adjusted by dividing the covered numbers by 38 instead of 37 (e.g., straight-up bet probability decreases to approximately 2.63%), while payouts remain the same.[43][75]| Bet Name | Numbers Covered (Count) | Payout Ratio | European Probability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outside Bets | |||

| Red or Black | 18 red or 18 black (excludes 0) | 1:1 | 48.65% |

| Odd or Even | 18 odd or 18 even (excludes 0) | 1:1 | 48.65% |

| High (19-36) or Low (1-18) | 18 high or 18 low (excludes 0) | 1:1 | 48.65% |

| Dozen (1-12, 13-24, 25-36) | 12 consecutive in a dozen (excludes 0) | 2:1 | 32.43% |

| Column | 12 in a vertical column (excludes 0) | 2:1 | 32.43% |

| Inside Bets | |||

| Straight-Up | 1 specific number | 35:1 | 2.70% |

| Split | 2 adjacent numbers | 17:1 | 5.41% |

| Street (Line) | 3 consecutive numbers in a row | 11:1 | 8.11% |

| Corner (Square) | 4 numbers forming a square | 8:1 | 10.81% |

| Six Line (Double Street) | 6 consecutive numbers across two streets | 5:1 | 16.22% |

| Announced Bets (European/French Wheels) | Varies | ||

| Voisins du Zéro | 17 numbers (0, 2-4, 7, 12, 15, 18, 19, 21, 22, 25, 26, 28, 29, 32, 35) | Varies: 35:1 (straight-up), 17:1 (split), 11:1 (street), 8:1 (corner) | 45.95% |

| Tiers du Cylindre | 12 numbers (5, 8, 10, 11, 13, 16, 23, 24, 27, 30, 33, 36) | Varies: primarily 17:1 (split) | 32.43% |

| Orphelins | 8 numbers (1, 6, 9, 14, 17, 20, 31, 34) | Varies: 35:1 (straight-up), 17:1 (split) | 21.62% |

| Jeu Zéro | 7 numbers (0, 3, 12, 15, 26, 32, 35) | Varies: 35:1 (straight-up), 17:1 (split) | 18.92% |

| Neighbors (5) | 5 consecutive numbers around a chosen one | 35:1 (straight-up) | 13.51% |

House Edge Calculation

The house edge in roulette represents the casino's average profit margin per unit wagered, derived from the expected value (EV) of each bet. The EV for a bet is calculated as , where is the probability of each outcome and is the corresponding payout (positive for wins, negative for losses). The house edge is then for a unit bet.[43][1] In European roulette, with 37 pockets (numbers 1-36 and a single 0), the house edge is uniform at approximately 2.70% for most bets, including even-money wagers like red/black or odd/even. For an even-money bet, the probability of winning is , yielding a payout of 1:1 (net +1 unit), while the probability of losing is (-1 unit). Thus, , so . This can also be expressed as , though the EV approach generalizes to all bet types.[43][1] American roulette introduces a double zero (00), expanding the wheel to 38 pockets and doubling the house edge to 5.26% for most bets. For even-money bets, the win probability drops to , with loss probability . The EV is , yielding . Exceptions include the five-number bet (0, 00, 1, 2, 3), which has a higher edge of 7.89% due to its payout structure not fully compensating for the five favorable outcomes out of 38.[43][1] The French roulette variant mitigates the house edge on even-money bets through the la partage rule, which returns half the wager if the ball lands on 0. Under this rule, the EV becomes , reducing the house edge to 1.35%. This applies only to even-money outside bets and does not affect other wagers, which retain the standard 2.70% edge.[43] Announced bets, such as voisins du zéro or tier, are combinations of underlying straight-up or split bets and thus inherit the same house edge as their components—2.70% in European/French roulette (or 5.26% in American, where applicable). For example, voisins du zéro covers nine numbers with varying units but maintains the overall edge through balanced probabilities and payouts equivalent to individual straight-up bets (35:1 payout, probability each).[43]Payout Structures

In roulette, payouts follow standardized ratios based on the bet type, ensuring consistent returns across casinos. A straight-up bet on a single number pays 35 to 1, returning the stake plus 35 times the wager amount if that number wins. Even-money outside bets, such as those on red or black, odd or even, or high or low, pay 1 to 1, doubling the stake for a win. These ratios apply universally in both European (single-zero) and American (double-zero) wheels, with the full payout including the original bet.[76][43] In physical casinos, winnings are distributed in colored chips unique to each player, where the value per chip is determined by dividing the buy-in by 20, forming standard stacks of 20 chips for efficient handling and payout. When multiple bets placed by a player win on the same outcome, each is settled independently without overlap penalties; for instance, a straight-up bet on the winning number pays 35 to 1, while a concurrent split bet covering that number and another pays 17 to 1 separately, allowing full returns on all valid wagers. This independent calculation prevents double-dipping by treating each chip placement as a distinct bet.[77][43] Outcomes involving the zero pocket alter payouts significantly: a straight-up bet on zero pays the standard 35 to 1, but all outside bets lose in full on zero (or double zero), except in variants with rules like en prison, where even-money bets may retain half the stake. This structure maintains the game's integrity by enforcing losses on non-winning categories.[43] Online roulette platforms deliver payouts as instant digital credits added to the player's account balance immediately after each spin, streamlining the process without physical handling. Certain online variants feature progressive jackpots, where a small deduction from qualifying bets accumulates into a shared prize pool that triggers additional large wins beyond standard ratios, often randomly or on specific outcomes.[76][78]Mathematical Foundations

Probability Model