Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Expurgation

View on Wikipedia

An expurgation of a work, also known as a bowdlerization or fig-leafing, is a form of censorship that involves purging anything deemed noxious or offensive from an artistic work or other type of writing or media.[1][2][3][4]

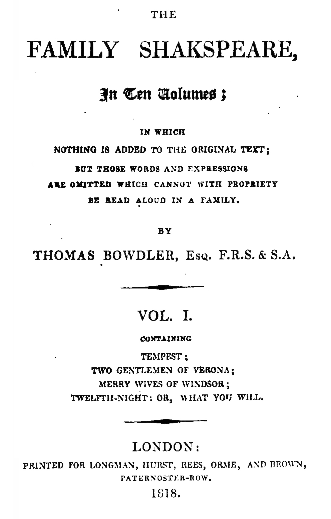

The term bowdlerization is often used in the context of the expurgation of lewd material from books.[5] The term derives from Thomas Bowdler's 1818 edition of William Shakespeare's plays, which he reworked in ways that he felt were more suitable for women and children.[6] He similarly edited Edward Gibbon's Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire.[7] A less common term used in this context, also based on common editorial practice, is Ad usum Delphini, referring to a series of consciously censored classical works.[8][9]

Another term used in related discourse is censorship by so-called political correctness.[10] When this practice is adopted voluntarily, by publishers of new editions or translators, it is seen as a form of self-censorship.[3][11] Texts subject to expurgation are derivative works, sometimes subject to renewed copyright protection.[12]

Examples

[edit]Religious

[edit]- In 1264, Pope Clement IV ordered the Jews of the Crown of Aragon to submit their books to Dominican censors for expurgation.[13][14][15]

Sexual

[edit]- Due to its mockery of the ancestors of the modern British royal family,[16] graphic descriptions of sex acts, and the symptoms of venereal disease,[17] the 1751 Scottish Gaelic poetry book Ais-eridh na Sean Chánoin Albannaich ("The Resurrection of the Old Scottish Language") by Alasdair mac Mhaighstir Alasdair, national poet of Scotland, continued to be republished only in heavily bowdlerized editions by puritanical censors throughout the 18th and 19th centuries.[18] The first uncensored text was published only in 2020.[19]

- "The Crabfish" (known also as "The Sea Crabb"), an English folk song dating back to the mid-1800s about a man who places a crab into a chamber pot, unbeknownst to his wife, who later uses the pot without looking, and is attacked by the crab.[20] Over the years, sanitized versions of the song were released in which a lobster or crab grabs the wife by the nose[21] instead of by the genitals,[20] and others in which each potentially offensive word is replaced with an inoffensive word that does not fit the rhyme scheme, thus implying that there is a correct word that does rhyme. For instance, "Children, children, bring the looking glass / Come and see the crayfish that bit your mother's a-face" (arse).[22]

- The 1925 Harvard Press edition of Montaigne's essays (translated by George Burnham Ives) omitted the essays that pertain to sex.[23]

- A Boston-area ban on Upton Sinclair's novel Oil! – owing to a short motel sex scene – prompted the author to assemble a 150-copy fig-leaf edition with the nine offending pages blacked out as a publicity stunt.[24][25]

- In 1938, a jazz song "Flat Foot Floogie (with a Floy Floy)" peaked at number two on US charts. The original lyrics were sung with the word "floozie", meaning a sexually promiscuous woman, or a prostitute, but record company Vocalion objected. Hence the word was substituted with the almost similar sounding title word "floogie" in the second recording. The "floy floy" in the title was a slang term for a venereal disease, but that was not widely known at the time. In the lyrics it is sung repeatedly "floy-doy", which was widely thought as a nonsense refrain. Since the lyrics were regarded as nonsense the song failed to catch the attention of censors.

- In 1920, an American publisher bowdlerized the George Ergerton translation of Knut Hamsun's Hunger.[26]

- Lady Chatterley's Lover by English author D. H. Lawrence. An unexpurgated edition was not published openly in the United Kingdom until 1960.

- Several music artists have changed song titles to appease radio stations. For example, an expurgated remix of Snoop Dogg's song "Wet" was released under the title "Sweat" and Rihanna's song "S&M" had to be changed to "C'mon" in the UK.[27]

Racial

[edit]- Recent editions of many works—including Mark Twain's Huckleberry Finn[28] and Joseph Conrad's Nigger of the Narcissus—have found various replacements ("slave", "Indian", "soldier boy", "N-word", "children") for the word nigger. An example of bowdlerization can be plainly seen in Huckleberry Finn, in which Twain used racial slurs in natural speech to highlight what he saw as racism and prejudice endemic to the Antebellum South.[29][30]

- Agatha Christie's 1939 book Ten Little Niggers was titled And Then There Were None for the US market in 1940, with some paperback editions calling it Ten Little Indians. UK editions continued to use the original title into the 1980s, and French editions were called Dix Petits Nègres until 2020.[31]

- The American version of the counting rhyme "Eeny, meeny, miny, moe", which was changed by some to add the word "nigger",[32] is now sung with a different word, such as "tiger".

- The Hardy Boys children's mystery novels (published starting in 1927) contained heavy doses of racism. They were extensively revised starting in 1959 in response to parents' complaints about racial stereotypes in the books.[33] For further information, see The Hardy Boys#1959–1979.

- The Story of Doctor Dolittle and relevant works have been reedited to remove controversial references to and plots related to non-white characters (in particular, African ones).[34][35]

Cursing

[edit]- Many Internet message boards and forums use automatic wordfiltering to block offensive words and phrases from being published or automatically amend them to more innocuous substitutes such as asterisks or nonsense. This often catches innocent words, in a scenario referred to as the Scunthorpe problem: words such as 'assassinate' and 'classic' may become 'buttbuttinate' or 'clbuttic'. Users frequently self-bowdlerize their own writing by using slight misspellings, minced oaths or variants, such as 'flek', 'fcuk' or 'pron'.[36][37]

- In a similar vein, content creators feel that the algorithms that spread their content or make it fit for revenue may turn against them, if certain topics are mentioned, prompting them to come up with euphemisms that may sound childish at times (a gynaecologist talking about lady bits to avoid vagina mistakenly prompting the algorithm to think the matter is too obscene to be worth broadcasting) or bizarre (a video-essay on a murder may reference the act as un-aliving)

- The 2010 song "Fuck You" by CeeLo Green, which made the top-10 in thirteen countries, was broadcast as "Forget You", with a matching music video, where the changed lyrics cannot be lip-read, as insisted on by the record company.[38]

- The 2021 song "ABCDEFU" by Gayle was also bowdlerized for radio, with the new lyrics reading: 'A, B, C, D, E, forget you', in a similar fashion to Fuck You.[39]

Other

[edit]- A student edition of the 1953 novel Fahrenheit 451 was expurgated to remove a variety of content. This was ironic given the subject matter of the novel involves burning books. This continued for a dozen years before it was brought to author Ray Bradbury's attention and he convinced the publisher to reinstate the material.[40][41][42][43]

- The 2017 video game South Park: The Fractured but Whole was originally going to have the name The Butthole of Time. However, marketers would not promote anything with a vulgarity in its title, so "butthole" was replaced with the homophone "but whole".[44][45]

- In 2023 new versions of Roald Dahl's books were published by Puffin Books to remove language deemed inappropriate. Puffin had hired sensitivity readers to go over his texts to make sure the books could "continue to be enjoyed by all today".[46] The same was done with the James Bond novels.[47]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Salvador, Roberto (13 June 2023). "Censorship and Expurgation of the Selected Children's Literature". The Quest: Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Development. 2 (1). doi:10.60008/thequest.v2i1.57. ISSN 1908-3211.

- ^ Sturm, Michael O. (1983). "Censorship: Where Do We Stand?". American Secondary Education. 12 (3): 5–8. ISSN 0003-1003. JSTOR 41063608.

- ^ a b Merkle, Denise (2001). "When expurgation constitutes ineffective censorship: the case of three Vizetelly translations of Zola". In Thelen, Marcel (ed.). Translation and meaning. 5: Proceedings of the Maastricht session of the 3rd International Maastricht-Łódz Duo Colloquium on "Translation and Meaning", held in Maastricht, The Netherlands, 26 - 29 April 2000 / Marcel Thelen .. ed (PDF). Maastricht: Euroterm. ISBN 978-90-801039-4-8.

- ^ "Expurgation of Library Resources: An Interpretation of the Library Bill of Rights | ALA". www.ala.org. Retrieved 21 August 2024.

- ^ Goldstein, Kenneth S. (1967). "Bowdlerization and Expurgation: Academic and Folk". The Journal of American Folklore. 80 (318): 374–386. doi:10.2307/537416. ISSN 0021-8715. JSTOR 537416.

- ^ Wheeler, Kip. "Censorship and Bowdlerization" (PDF). Jefferson City, Tennessee, USA: Carson-Newman University. p. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 March 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ Gibbon, Edward (1826). Gibbon's History of the decline and fall of the Roman empire, repr. with the omission of all passages of an irreligious or immoral tendency, by T. Bowdler. pp. i, iii.

- ^ Hollewand, Karen E. (11 March 2019), "Scholarship", The Banishment of Beverland, Brill, pp. 109–168, ISBN 978-90-04-39632-6, retrieved 21 August 2024

- ^ Harrison, Stephen; Pelling, Christopher, eds. (2021). Classical Scholarship and Its History. doi:10.1515/9783110719215. ISBN 978-3-11-071921-5. Retrieved 21 August 2024.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ Essi, Cedric (December 2018). "Queer Genealogies across the Color Line and into Children's Literature: Autobiographical Picture Books, Interraciality, and Gay Family Formation". Genealogy. 2 (4): 43. doi:10.3390/genealogy2040043. ISSN 2313-5778.

- ^ Woods, Michelle (2019). "Censorship". In Washbourne, R. Kelly; Van Wyke, Benjamin (eds.). The Routledge handbook of literary translation. Routledge handbooks in translation and interpreting studies. London New York, NY: Routledge. pp. 511–523. doi:10.4324/9781315517131-34. ISBN 978-1-315-51713-1.

- ^ Smith, Cathay Y. N. (12 January 2024). "Editing Classic Books: A Threat to the Public Domain? - Virginia Law Review". virginialawreview.org. Retrieved 21 August 2024.

- ^ Popper, William (May 1889). The Censorship of Hebrew Books (1st ed.). New Rochelle, New York, USA: Knickerbocker Press. pp. 13–14. OCLC 70322240. OL 23428412M.

- ^ Greenfield, Jeanette (26 January 1996). The Return of Cultural Treasures. England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-47746-8.

- ^ Carus, Paul (1925). The Open Court. Open Court Publishing Company.

- ^ Charles MacDonald (2011), Moidart: Among the Clanranalds, Birlinn Limited. pp. 129-130.

- ^ Derek S. Thomson (1983), The Companion to Gaelic Scotland, page 185.

- ^ The Scottish Poetry Library interviews Alan Riach about Alasdair mac Mhaighstir Alasdair, June 2016.

- Willies, ghillies and horny Highlanders: Scottish Gaelic writing has a filthy past by Peter MacKay, University of St. Andrews, The Conversation, 24 October 2017.

- ^ Aiseirigh: Òrain le Alastair Mac Mhaighstir Alastair, The Gaelic Books Council.

- ^ a b Frederick J. Furnivall, ed. (1867). Bishop Percy's Folio Manuscript: loose and humorous songs. London. p. 100.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Feierabend, John M. (1 April 2004). The Crabfish. Illustrated by Vincent Ngyen. Gia Publications. ISBN 9781579993832. OCLC 59550589.

- ^ "The Crayfish". Archived from the original on 9 April 2022. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- ^ Bussacco, Michael C. (2009). Heritage Press Sandglass Companion Book: 1960–1983. Tribute Books (Archibald, Penn.). p. 252. ISBN 9780982256510. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- ^ Curtis, Jack (17 February 2008). "Blood from Oil". The Boston Globe. Boston, Massachusetts, USA. ISSN 0743-1791. OCLC 66652431. Archived from the original on 11 July 2016. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- ^ Sinclair, Mary Craig (1957). Southern Belle. New York: Crown Publishers. p. 309. ISBN 9781578061525. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Lyngstad, Sverre (2005). Knut Hamsun, Novelist: A Critical Assessment. Peter Lang. ISBN 978-0-8204-7433-5.

- ^ "When Artists Are Forced to Change Song Titles". BET. Retrieved 21 October 2023.

- ^ Tomasky, Michael (7 January 2011). "The New Huck Finn". The Guardian. London, England. ISSN 1756-3224. OCLC 60623878. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 6 September 2013.

- ^ Lowenthal, David (October 2015). The Past is a Foreign Country - Revisited. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85142-8.

- ^ Fulton, Joe B. (1997). Mark Twain's Ethical Realism: The Aesthetics of Race, Class, and Gender. University of Missouri Press. ISBN 978-0-8262-1144-6.

- ^ "'N-word' scrapped from French edition of Agatha Christie novel". RFI. 26 August 2020. Retrieved 24 April 2025.

- ^ Opie, Iona; Opie, Peter (30 October 1997). The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes (2nd ed.). England: Oxford University Press. pp. 156–8. ISBN 0198600887. OL 432879M. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ Rehak, Melanie (2005). Girl Sleuth: Nancy Drew and the Women Who Created Her (1st ed.). Harcourt, Orlando, Florida, USA: Harvest (published 2006). p. 243. ISBN 9780156030564. OCLC 769190422. OL 29573540M. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ Lanes, Selma G. "Doctor Dolittle, Innocent Again", New York Times. August 28, 1988.

- ^ Smith, Cathay Y. N. (12 January 2024). "Editing Classic Books: A Threat to the Public Domain? - Virginia Law Review". virginialawreview.org. Retrieved 21 August 2024.

- ^ Pourciau, Lester J. (1999). Ethics and Electronic Information in the Twenty-first Century. Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-55753-138-4.

- ^ Ng, Jason (27 August 2013). Blocked on Weibo: What Gets Suppressed on ChinaÕs Version of Twitter (And Why). New Press, The. ISBN 978-1-59558-871-5.

- ^ Smith, Caspar Llewellyn (14 November 2010). "Cee Lo Green: 'I've been such an oddball my whole life' | Q&A". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 10 October 2020.

- ^ Hirsh, Marc (11 March 2022). "Gayle's 'abcdefu' and 10 More Extremely Cursed Radio Edits". Vulture. Retrieved 29 March 2025.

- ^ Crider, Bill (Fall 1980). Lee, Billy C.; Laughlin, Charlotte (eds.). "Reprints/Reprints: Ray Bradbury's FAHRENHEIT 451". Paperback Quarterly. III (3): 25. ISBN 9781434406330. Archived from the original on 4 May 2021. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

The censorship began with a special 'Bal-Hi' edition in 1967, an edition designed for high school students...

- ^ Karolides, Nicholas J.; Bald, Margaret; Sova, Dawn B. (2011). 120 Banned Books: Censorship Histories of World Literature (Second ed.). Checkmark Books. p. 488. ISBN 978-0-8160-8232-2.

In 1967, Ballantine Books published a special edition of the novel to be sold in high schools. Over 75 passages were modified to eliminate such words as hell, damn, and abortion, and two incidents were eliminated. The original first incident described a drunk man who was changed to a sick man in the expurgated edition. In the second incident, reference is made to cleaning fluff out of the human navel, but the expurgated edition changed the reference to cleaning ears.

- ^ Greene, Bill (February 2007). "The mutilation and rebirth of a classic: Fahrenheit 451". Compass: New Directions at Falvey. III (3). Villanova University. Archived from the original on 11 February 2021. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- ^ Karolides, Nicholas J.; Bald, Margaret; Sova, Dawn B. (2011). 120 Banned Books: Censorship Histories of World Literature (Second ed.). Checkmark Books. p. 488. ISBN 978-0-8160-8232-2.

After six years of simultaneous editions, the publisher ceased publication of the adult version, leaving only the expurgated version for sale from 1973 through 1979, during which neither Bradbury nor anyone else suspected the truth.

- ^ "South Park: The Fractured But Whole was originally called South Park: The Butthole of Time". VideoGamer.com. 25 July 2016. Retrieved 25 December 2021.

- ^ "'South Park: The Fractured But Whole' game – everything you need to know". NME. 25 September 2017. Retrieved 25 December 2021.

- ^ Rawlinson, Kevin; Banfield-Nwachi, Mabel; Shaffi, Sarah (20 February 2023). "Rishi Sunak joins criticism of changes to Roald Dahl books". The Guardian. London, England. ISSN 1756-3224. OCLC 60623878. Archived from the original on 21 February 2023. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- ^ Haring, Bruce (26 February 2023). "James Bond Books Edited To Avoid Offense To Modern Audiences – Report". Deadline. USA: Penske Media Corporation. Archived from the original on 28 February 2023. Retrieved 26 February 2023.