Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Scottish Gaelic

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2023) |

| Scottish Gaelic | |

|---|---|

| |

| Gàidhlig | |

| Pronunciation | [ˈkaːlɪkʲ] |

| Native to | United Kingdom, Canada |

| Region | Scotland; Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia |

| Ethnicity | Scottish Gaels |

| Speakers | 70,000 L1 and L2 speakers in Scotland (2022)[1] 130,000 people in Scotland reported having some Gaelic language ability in 2022;[1] 1,300 fluent in Nova Scotia[2] |

Indo-European

| |

Early forms | |

| Dialects |

|

| |

| Official status | |

Official language in | Scotland |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | gd |

| ISO 639-2 | gla |

| ISO 639-3 | gla |

| Glottolog | scot1245 |

| ELP | Scottish Gaelic |

| Linguasphere | 50-AAA |

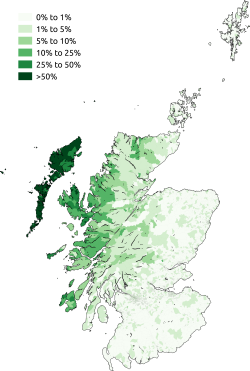

2022 distribution of people with skills in Gaelic in Scotland | |

Scottish Gaelic is classified as Definitely Endangered by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger.[3] | |

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Scotland |

|---|

|

| People |

| Mythology and folklore |

| Cuisine |

| Religion |

| Art |

| Literature |

Scottish Gaelic (/ˈɡælɪk/ ⓘ GAL-ik; endonym: Gàidhlig [ˈkaːlɪkʲ] ⓘ), also known as Scots Gaelic or simply Gaelic, is a Celtic language native to the Gaels of Scotland. As a member of the Goidelic branch of Celtic, Scottish Gaelic, alongside both Irish and Manx, developed out of Old Irish.[4] It became a distinct spoken language sometime in the 13th century in the Middle Irish period, although a common literary language was shared by the Gaels of both Ireland and Scotland until well into the 17th century.[5] Most of modern Scotland was once Gaelic-speaking, as evidenced especially by Gaelic-language place names.[6][7]

In the 2011 census of Scotland, 57,375 people (1.1% of the Scottish population, three years and older) reported being able to speak Gaelic, 1,275 fewer than in 2001. The highest percentages of Gaelic speakers were in the Outer Hebrides. Nevertheless, there is a language revival, and the number of speakers of the language under age 20 did not decrease between the 2001 and 2011 censuses.[8] In the 2022 census of Scotland, it was found that 2.5% of the Scottish population had some skills in Gaelic,[9] or 130,161 persons. Of these, 69,701 people reported speaking the language, with a further 46,404 people reporting that they understood the language, but did not speak, read, or write in it.[10]

Outside of Scotland, a dialect known as Canadian Gaelic has been spoken in Canada since the 18th century. In the 2021 census, 2,170 Canadian residents claimed knowledge of Scottish Gaelic, a decline from 3,980 speakers in the 2016 census.[11][12] There exists a particular concentration of speakers in Nova Scotia, with historic communities in other parts of North America, including North Carolina and Glengarry County, Ontario having largely disappeared.[13]

Scottish Gaelic is classed as an indigenous language under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages, which the UK Government has ratified, and the Gaelic Language (Scotland) Act 2005 established a language-development body, Bòrd na Gàidhlig.[14] With the passing of the Scottish Languages Act 2025, Gaelic, alongside Scots, has become an official language of Scotland.[15]

Name

[edit]Aside from "Scottish Gaelic", the language may also be referred to simply as "Gaelic", pronounced /ˈɡælɪk/ GA-lik in English. However, "Gaelic" /ˈɡeɪlɪk/ GAY-lik also refers to the Irish language (Gaeilge)[16] and the Manx language (Gaelg).

Scottish Gaelic is distinct from Scots, the Middle English-derived language which had come to be spoken in most of the Lowlands of Scotland by the early modern era. Prior to the 15th century, this language was known as Inglis ("English")[17] by its own speakers, with Gaelic being called Scottis ("Scottish"). Beginning in the late 15th century, it became increasingly common for such speakers to refer to Scottish Gaelic as Erse ("Irish") and the Lowland vernacular as Scottis.[18] Today, Scottish Gaelic is recognised as a separate language from Irish, so the word Erse in reference to Scottish Gaelic is no longer used.[19]

History

[edit]Origins

[edit]

Based on medieval traditional accounts and the apparent evidence from linguistic geography, Gaelic has been commonly believed to have been brought to Scotland in the 4th and 5th centuries CE by settlers from Ireland who founded the Gaelic kingdom of Dál Riata on Scotland's west coast, in what is present-day Argyll.[20]: 551 [21]: 66 An alternative view has been voiced by archaeologist Ewan Campbell, who has argued that the putative migration or takeover is not reflected in archaeological or placename data (as pointed out earlier by Leslie Alcock). Campbell has also questioned the age and reliability of the medieval historical sources speaking of a conquest. Instead, he has inferred that Argyll formed part of a common Q-Celtic-speaking area with Ireland, connected rather than divided by the sea, since the Iron Age.[22] These arguments have been opposed by some scholars defending the early dating of the traditional accounts and arguing for other interpretations of the archaeological evidence.[23]

Regardless of how it came to be spoken in the region, Gaelic in Scotland was mostly confined to Dál Riata until the eighth century, when it began expanding into Pictish areas north of the Firth of Forth and the Firth of Clyde. During the reign of Caustantín mac Áeda (Constantine II, 900–943), outsiders began to refer to the region as the kingdom of Alba rather than as the kingdom of the Picts. However, though the Pictish language did not disappear suddenly, a process of Gaelicisation (which may have begun generations earlier) was clearly under way during the reigns of Caustantín and his successors. By a certain point, probably during the 11th century, all the inhabitants of Alba had become fully Gaelicised Scots, and Pictish identity was forgotten.[24] Bilingualism in Pictish and Gaelic, prior to the former's extinction, led to the presence of Pictish loanwords in Scottish Gaelic[25] and syntactic influence[26] which could be considered to constitute a Pictish substrate.[27]

In 1018, after the conquest of Lothian (theretofore part of England and inhabited predominantly by speakers of Northumbrian Old English) by the Kingdom of Scotland, Gaelic reached its social, cultural, political, and geographic zenith.[28]: 16–18 Colloquial speech in Scotland had been developing independently of that in Ireland since the eighth century.[29] For the first time, the entire region of modern-day Scotland was called Scotia in Latin, and Gaelic was the lingua Scotica.[30]: 276 [31]: 554 In southern Scotland, Gaelic was strong in Galloway, adjoining areas to the north and west, West Lothian, and parts of western Midlothian. It was spoken to a lesser degree in north Ayrshire, Renfrewshire, the Clyde Valley and eastern Dumfriesshire. In south-eastern Scotland, there is no evidence that Gaelic was ever widely spoken.[32]

Decline

[edit]Many historians mark the reign of King Malcolm Canmore (Malcolm III) between 1058 and 1093 as the beginning of Gaelic's eclipse in Scotland. His wife Margaret of Wessex spoke no Gaelic, gave her children Anglo-Saxon rather than Gaelic names, and brought many English bishops, priests, and monastics to Scotland.[28]: 19 During the reigns of Malcolm Canmore's sons, Edgar, Alexander I and David I (their successive reigns lasting 1097–1153), Anglo-Norman names and practices spread throughout Scotland south of the Forth–Clyde line and along the northeastern coastal plain as far north as Moray. Norman French completely displaced Gaelic at court. The establishment of royal burghs throughout the same area, particularly under David I, attracted large numbers of foreigners speaking Old English. This was the beginning of Gaelic's status as a predominantly rural language in Scotland.[28]: 19–23

Clan chiefs in the northern and western parts of Scotland continued to support Gaelic bards who remained a central feature of court life there. The semi-independent Lordship of the Isles in the Hebrides and western coastal mainland remained thoroughly Gaelic since the language's recovery there in the 12th century, providing a political foundation for cultural prestige down to the end of the 15th century.[31]: 553–6

- Note: Caithness Norn as shown in the orange was also spoken in the 1400s in the same region as the 1500s' picture, but its presence, exact timeline, and mixture with Scottish Gaelic is debated*

By the mid-14th century what eventually came to be called Scots (at that time termed Inglis) emerged as the official language of government and law.[33]: 139 Scotland's emergent nationalism in the era following the conclusion of the Wars of Scottish Independence was organized using Scots as well. For example, the nation's great patriotic literature including John Barbour's The Brus (1375) and Blind Harry's The Wallace (before 1488) was written in Scots, not Gaelic. By the end of the 15th century, English/Scots speakers referred to Gaelic instead as 'Yrisch' or 'Erse', i.e. Irish and their own language as 'Scottis'.[28]: 19–23

Modern era

[edit]A steady shift away from Scottish Gaelic continued into and through the modern era. Some of this was driven by policy decisions by government or other organisations, while some originated from social changes. In the last quarter of the 20th century, efforts began to encourage use of the language.

The Statutes of Iona, enacted by James VI in 1609, was one piece of legislation that addressed, among other things, the Gaelic language. It required the heirs of clan chiefs to be educated in lowland, Protestant, English-speaking schools. James VI took several such measures to impose his rule on the Highland and Island region. In 1616, the Privy Council proclaimed that schools teaching in English should be established. Gaelic was seen, at this time, as one of the causes of the instability of the region. It was also associated with Catholicism.[34]: 110–113

The Society in Scotland for the Propagation of Christian Knowledge (SSPCK) was founded in 1709. They met in 1716, immediately after the failed Jacobite rising of 1715, to consider the reform and civilisation of the Highlands, which they sought to achieve by teaching English and the Protestant religion. Initially, their teaching was entirely in English, but soon the impracticality of educating Gaelic-speaking children in this way gave rise to a modest concession: in 1723, teachers were allowed to translate English words in the Bible into Gaelic to aid comprehension, but there was no further permitted use. Other less prominent schools worked in the Highlands at the same time, also teaching in English. This process of anglicisation paused when evangelical preachers arrived in the Highlands, convinced that people should be able to read religious texts in their own language. The first well known translation of the Bible into Scottish Gaelic was made in 1767, when James Stuart of Killin and Dugald Buchanan of Rannoch produced a translation of the New Testament. In 1798, four tracts in Gaelic were published by the Society for Propagating the Gospel at Home, with 5,000 copies of each printed. Other publications followed, with a full Gaelic Bible in 1801. The influential and effective Gaelic Schools Society was founded in 1811. Their purpose was to teach Gaels to read the Bible in their own language. In the first quarter of the 19th century, the SSPCK (despite their anti-Gaelic attitude in prior years) and the British and Foreign Bible Society distributed 60,000 Gaelic Bibles and 80,000 New Testaments.[35]: 98 It is estimated that this overall schooling and publishing effort gave about 300,000 people in the Highlands some basic literacy.[34]: 110–117 Very few European languages have made the transition to a modern literary language without an early modern translation of the Bible; the lack of a well known translation may have contributed to the decline of Scottish Gaelic.[36]: 168–202

Counterintuitively, access to schooling in Gaelic increased knowledge of English. In 1829, the Gaelic Schools Society reported that parents were unconcerned about their children learning Gaelic, but were anxious to have them taught English. The SSPCK also found Highlanders to have significant prejudice against Gaelic. T. M. Devine attributes this to an association between English and the prosperity of employment: the Highland economy relied greatly on seasonal migrant workers travelling outside the Gàidhealtachd. In 1863, an observer sympathetic to Gaelic stated that "knowledge of English is indispensable to any poor islander who wishes to learn a trade or to earn his bread beyond the limits of his native Isle". Generally, rather than Gaelic speakers, it was Celtic societies in the cities and professors of Celtic from universities who sought to preserve the language.[34]: 116–117

The Education (Scotland) Act 1872 provided universal education in Scotland, but completely ignored Gaelic in its plans. The mechanism for supporting Gaelic through the Education Codes issued by the Scottish Education Department were steadily used to overcome this omission, with many concessions in place by 1918. However, the members of Highland school boards tended to have anti-Gaelic attitudes and served as an obstacle to Gaelic education in the late 19th and early 20th century.[34]: 110–111

Loss of life due to World War I and the 1919 sinking of the HMY Iolaire, combined with emigration, resulted in the 1910s seeing unprecedented damage to the use of Scottish Gaelic, with a 46% fall in monolingual speakers and a 19% fall in bilingual speakers between the 1911 and 1921 Censuses.[37] Michelle MacLeod of Aberdeen University has said that there was no other period with such a high fall in the number of monolingual Gaelic speakers: "Gaelic speakers became increasingly the exception from that point forward with bilingualism replacing monolingualism as the norm for Gaelic speakers."[37]

The Linguistic Survey of Scotland (1949–1997) surveyed both the dialect of the Scottish Gaelic language, and also mixed use of English and Gaelic across the Highlands and Islands.[38]

Defunct dialects

[edit]Dialects of Lowland Gaelic have been defunct since the 18th century. Gaelic in the Eastern and Southern Scottish Highlands, although alive until the mid-20th century, is now largely defunct. Although modern Scottish Gaelic is dominated by the dialects of the Outer Hebrides and Isle of Skye, there remain some speakers of the Inner Hebridean dialects of Tiree and Islay, and even a few native speakers from Western Highland areas including Wester Ross, northwest Sutherland, Lochaber and Argyll. Dialects on both sides of the Straits of Moyle (the North Channel) linking Scottish Gaelic with Irish are now extinct, though native speakers were still to be found on the Mull of Kintyre, on Rathlin and in North East Ireland as late as the mid-20th century. Records of their speech show that Irish and Scottish Gaelic existed in a dialect chain with no clear language boundary.[39] Some features of moribund dialects have been preserved in Nova Scotia, including the pronunciation of the broad or velarised l (l̪ˠ) as [w], as in the Lochaber dialect.[40]: 131

Status

[edit]

The Endangered Languages Project lists Gaelic's status as "threatened", with "20,000 to 30,000 active users".[41][42][better source needed] UNESCO classifies Gaelic as "definitely endangered".[43]

Number of speakers

[edit]| Year | Scottish population | Monolingual Gaelic speakers | Gaelic and English bilinguals | Total Gaelic language group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1755 | 1,265,380 | Unknown | Unknown | 289,798 | 22.9% | ||

| 1800 | 1,608,420 | Unknown | Unknown | 297,823 | 18.5% | ||

| 1881 | 3,735,573 | Unknown | Unknown | 231,594 | 6.1% | ||

| 1891 | 4,025,647 | 43,738 | 1.1% | 210,677 | 5.2% | 254,415 | 6.3% |

| 1901 | 4,472,103 | 28,106 | 0.6% | 202,700 | 4.5% | 230,806 | 5.1% |

| 1911 | 4,760,904 | 8,400 | 0.2% | 183,998 | 3.9% | 192,398 | 4.2% |

| 1921 | 4,573,471 | 9,829 | 0.2% | 148,950 | 3.3% | 158,779 | 3.5% |

| 1931 | 4,588,909 | 6,716 | 0.2% | 129,419 | 2.8% | 136,135 | 3.0% |

| 1951 | 5,096,415 | 2,178 | 0.1% | 93,269 | 1.8% | 95,447 | 1.9% |

| 1961 | 5,179,344 | 974 | <0.1% | 80,004 | 1.5% | 80,978 | 1.5% |

| 1971 | 5,228,965 | 477 | <0.1% | 88,415 | 1.7% | 88,892 | 1.7% |

| 1981 | 5,035,315 | — | — | 82,620 | 1.6% | 82,620 | 1.6% |

| 1991 | 5,083,000 | — | — | 65,978 | 1.4% | 65,978 | 1.4% |

| 2001 | 5,062,011 | — | — | 58,652 | 1.2% | 58,652 | 1.2% |

| 2011 | 5,295,403 | — | — | 57,602 | 1.1% | 57,602 | 1.1% |

| 2022 | 5,447,700 | — | — | 69,701 | 1.3% | 69,701 | 1.3% |

The 1755–2001 figures are census data quoted by MacAulay.[44]: 141 The 2011 Gaelic speakers figures come from table KS206SC of the 2011 Census. The 2011 total population figure comes from table KS101SC. The numbers of Gaelic speakers relate to the numbers aged 3 and over, and the percentages are calculated using those and the number of the total population aged 3 and over.

Across the whole of Scotland, the 2011 census showed that 25,000 people (0.49% of the population) used Gaelic at home. Of these, 63.3% said that they had a full range of language skills: speaking, understanding, reading and writing Gaelic. 40.2% of Scotland's Gaelic speakers said that they used Gaelic at home. To put this in context, the most common language spoken at home in Scotland after English and Scots is Polish, with about 1.1% of the population, or 54,000 people.[45][46] In 2022, the census showed that 3,551 people recorded Gaelic as their 'main language'.[47] In Stornoway, 195 people out of 6,796 residents aged 3 and over listed Gaelic as their main language, 2.9% of the population. In Na h-Eileanan Siar (the Outer Hebrides) in general, 1,761 out of 25,563 residents indicated it as their main language, or 6.9% of the population. Most (1,011) of these were 65 years and older.[48]

Distribution in Scotland

[edit]The 2011 UK Census showed a total of 57,375 Gaelic speakers in Scotland (1.1% of population over three years old), of whom only 32,400 could also read and write the language.[49] Compared with the 2001 Census, there has been a diminution of about 1300 people.[50] This is the smallest drop between censuses since the Gaelic-language question was first asked in 1881. The Scottish government's language minister and Bòrd na Gàidhlig took this as evidence that Gaelic's long decline has slowed.[51]

The main stronghold of the language continues to be the Outer Hebrides (Na h-Eileanan Siar), where the overall proportion of speakers is 52.2%. Important pockets of the language also exist in the Highlands (5.4%) and in Argyll and Bute (4.0%) and Inverness (4.9%). The locality with the largest absolute number is Glasgow with 5,878 such persons, who make up over 10% of all of Scotland's Gaelic speakers.

Gaelic continues to decline in its traditional heartland. Between 2001 and 2011, the absolute number of Gaelic speakers fell sharply in the Western Isles (−1,745), Argyll & Bute (−694), and Highland (−634). The drop in Stornoway, the largest parish in the Western Isles by population, was especially acute, from 57.5% of the population in 1991 to 43.4% in 2011.[52] The only parish outside the Western Isles over 40% Gaelic-speaking is Kilmuir in Northern Skye at 46%. The islands in the Inner Hebrides with significant percentages of Gaelic speakers are Tiree (38.3%), Raasay (30.4%), Skye (29.4%), Lismore (26.9%), Colonsay (20.2%), and Islay (19.0%).

Today, no civil parish in Scotland has a proportion of Gaelic speakers greater than 65% (the highest value is in Barvas, Lewis, with 64.1%). In addition, no civil parish on mainland Scotland has a proportion of Gaelic speakers greater than 20% (the highest is in Ardnamurchan, Highland, with 19.3%). Out of a total of 871 civil parishes in Scotland, the proportion of Gaelic speakers exceeds 50% in seven parishes, 25% in 14 parishes, and 10% in 35 parishes.

Decline in traditional areas has recently been balanced by growth in the Scottish Lowlands. Between the 2001 and 2011 censuses, the number of Gaelic speakers rose in nineteen of the country's 32 council areas.[53] The largest absolute gains were in Aberdeenshire (+526), North Lanarkshire (+305), the Aberdeen City council area (+216), and East Ayrshire (+208). The largest relative gains were in Aberdeenshire (+0.19%), East Ayrshire (+0.18%), Moray (+0.16%), and Orkney (+0.13%).[citation needed]

In 2018, the census of pupils in Scotland showed 520 students in publicly funded schools had Gaelic as the main language at home, an increase of 5% from 497 in 2014. During the same period, Gaelic medium education in Scotland has grown, with 4,343 pupils (6.3 per 1000) being educated in a Gaelic-immersion environment in 2018, up from 3,583 pupils (5.3 per 1000) in 2014.[54] Data collected in 2007–2008 indicated that even among pupils enrolled in Gaelic medium schools, 81% of primary students and 74% of secondary students report using English more often than Gaelic when speaking with their mothers at home.[55] The effect on this of the significant increase in pupils in Gaelic-medium education since that time is unknown.

Preservation and revitalization

[edit]Gaelic Medium Education is one of the primary ways that the Scottish Government is addressing Gaelic language shift. Along with the Bòrd na Gàidhlig policies, preschool and daycare environments are also being used to create more opportunities for intergenerational language transmission in the Outer Hebrides.[56] However, revitalization efforts are not unified within Scotland or Nova Scotia, Canada.[57] One can attend Sabhal Mòr Ostaig, a national centre for Gaelic Language and Culture, based in Sleat, on the Isle of Skye. This institution is the only source for higher education which is conducted entirely in Scottish Gaelic.[58] They offer courses for Gaelic learners from beginners into fluency. They also offer regular bachelors and graduate programmes delivered entirely in Gaelic. Concerns have been raised around the fluency achieved by learners within these language programmes because they are disconnected from vernacular speech communities.[59][60] In regard to language revitalization planning efforts, many feel that the initiatives must come from within Gaelic speaking communities, be led by Gaelic speakers, and be designed to serve and increase fluency within the vernacular communities as the first and most viable resistance to total language shift from Gaelic to English.[57][59] Currently, language policies are focused on creating new language speakers through education, instead of focused on how to strengthen intergenerational transmission within existing Gaelic speaking communities.[57]

Challenges to preservation and revitalization

[edit]In the Outer Hebrides, accommodation ethics exist amongst native or local Gaelic speakers when engaging with new learners or non-locals.[59] Accommodation ethics, or ethics of accommodation, is a social practice where local or native speakers of Gaelic shift to speaking English when in the presence of non-Gaelic speakers out of a sense of courtesy or politeness. This accommodation ethic persists even in situations where new learners attempt to speak Gaelic with native speakers.[59] This creates a situation where new learners struggle to find opportunities to speak Gaelic with fluent speakers. Affect is the way people feel about something, or the emotional response to a particular situation or experience. For Gaelic speakers, there is a conditioned and socialized negative affect through a long history of negative Scottish media portrayal and public disrespect, state mandated restrictions on Gaelic usage, and highland clearances.[56][61][62] This negative affect towards speaking openly with non-native Gaelic speakers has led to a language ideology at odds with revitalization efforts on behalf of new speakers, state policies (such as the Gaelic Language Act), and family members reclaiming their lost mother tongue. New learners of Gaelic often have a positive affective stance to their language learning, and connect this learning journey towards Gaelic language revitalization.[63] The mismatch of these language ideologies, and differences in affective stance, has led to fewer speaking opportunities for adult language learners and therefore a challenge to revitalization efforts which occur outside the home. Positive engagements between language learners and native speakers of Gaelic through mentorship has proven to be productive in socializing new learners into fluency.[59][62]

Usage

[edit]Official

[edit]Scotland

[edit]In the 2022 census, 3,551 people claimed Gaelic as their 'main language.' Of these, 1,761 (49.6%) were in Na h-Eileanan Siar, 682 (19.2%) were in Highland, 369 were in Glasgow City and 120 were in City of Edinburgh; no other council area had as many as 80 such respondents.[64]

Scottish Parliament

[edit]

Gaelic has long suffered from its lack of use in educational and administrative contexts and was long suppressed.[65]

The UK government has ratified the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages in respect of Gaelic. Gaelic, along with Irish and Welsh, is designated under Part III of the Charter, which requires the UK Government to take a range of concrete measures in the fields of education, justice, public administration, broadcasting and culture. It has not received the same degree of official recognition from the UK Government as Welsh. With the advent of devolution, however, Scottish matters have begun to receive greater attention, and it achieved a degree of official recognition when the Gaelic Language (Scotland) Act was enacted by the Scottish Parliament on 21 April 2005.

The key provisions of the Act are:[66]

- Establishing the Gaelic development body, Bòrd na Gàidhlig (BnG), on a statutory basis with a view to securing the status of the Gaelic language as an official language of Scotland commanding equal respect to the English language and to promote the use and understanding of Gaelic.

- Requiring BnG to prepare a National Gaelic Language Plan every five years for approval by Scottish Ministers.

- Requiring BnG to produce guidance on Gaelic medium education and Gaelic as a subject for education authorities.

- Requiring public bodies in Scotland, both Scottish public bodies and cross-border public bodies insofar as they carry out devolved functions, to develop Gaelic language plans in relation to the services they offer, if requested to do so by BnG.

After its creation, Bòrd na Gàidhlig required a Gaelic Language Plan from the Scottish Government. This plan was accepted in 2008,[67] and some of its main commitments were: identity (signs, corporate identity); communications (reception, telephone, mailings, public meetings, complaint procedures); publications (PR and media, websites); staffing (language learning, training, recruitment).[67]

Following a consultation period, in which the government received many submissions, the majority of which asked that the bill be strengthened, a revised bill was published; the main alteration was that the guidance of the Bòrd is now statutory (rather than advisory). In the committee stages in the Scottish Parliament, there was much debate over whether Gaelic should be given 'equal validity' with English. Due to executive concerns about resourcing implications if this wording was used, the Education Committee settled on the concept of 'equal respect'. It is not clear what the legal force of this wording is.[citation needed]

The Act was passed by the Scottish Parliament unanimously, with support from all sectors of the Scottish political spectrum, on 21 April 2005. Under the provisions of the Act, it will ultimately fall to BnG to secure the status of the Gaelic language as an official language of Scotland.[citation needed]

Some commentators, such as Éamonn Ó Gribín (2006) argue that the Gaelic Act falls so far short of the status accorded to Welsh that one would be foolish or naïve to believe that any substantial change will occur in the fortunes of the language as a result of Bòrd na Gàidhlig's efforts.[68]

On 10 December 2008, to celebrate the 60th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the Scottish Human Rights Commission had the UDHR translated into Gaelic for the first time.[69]

However, given there are no longer any monolingual Gaelic speakers,[70] following an appeal in the court case of Taylor v Haughney (1982), involving the status of Gaelic in judicial proceedings, the High Court ruled against a general right to use Gaelic in court proceedings.[71]

While the goal of the Gaelic Language Act was to aid in revitalization efforts through government mandated official language status, the outcome of the act is distanced from the actual minority language communities.[60] It helps to create visibility of the minority language in civil structures, but does not impact or address the lived experiences of the Gaelic speaker communities wherein the revitalization efforts may have a higher return of new Gaelic speakers. Efforts are being made to concentrate resources, language planning, and revitalization efforts towards vernacular communities in the Western Isles.[60]

Qualifications in the language

[edit]The Scottish Qualifications Authority offer two streams of Gaelic examination across all levels of the syllabus: Gaelic for learners (equivalent to the modern foreign languages syllabus) and Gaelic for native speakers (equivalent to the English syllabus).[72][73]

An Comunn Gàidhealach performs assessment of spoken Gaelic, resulting in the issue of a Bronze Card, Silver Card or Gold Card. Syllabus details are available on An Comunn's website. These are not widely recognised as qualifications, but are required for those taking part in certain competitions at the annual mods.[74]

European Union

[edit]This section needs to be updated. The reason given is: The UK has now left the EU. (December 2020) |

In October 2009, a new agreement allowed Scottish Gaelic to be formally used between Scottish Government ministers and European Union officials. The deal was signed by Britain's representative to the EU, Sir Kim Darroch, and the Scottish government. This did not give Scottish Gaelic official status in the EU but gave it the right to be a means of formal communications in the EU's institutions. The Scottish government had to pay for the translation from Gaelic to other European languages. The deal was received positively in Scotland; Secretary of State for Scotland Jim Murphy said the move was a strong sign of the UK government's support for Gaelic. He said; "Allowing Gaelic speakers to communicate with European institutions in their mother tongue is a progressive step forward and one which should be welcomed".[75] Culture Minister Mike Russell said; "this is a significant step forward for the recognition of Gaelic both at home and abroad and I look forward to addressing the council in Gaelic very soon. Seeing Gaelic spoken in such a forum raises the profile of the language as we drive forward our commitment to creating a new generation of Gaelic speakers in Scotland."[76]

Signage

[edit]

Bilingual road signs, street names, business and advertisement signage (in both Gaelic and English) are gradually being introduced throughout Gaelic-speaking regions in the Highlands and Islands, including Argyll. In many cases, this has simply meant re-adopting the traditional spelling of a name (such as Ràtagan or Loch Ailleart rather than the anglicised forms Ratagan or Lochailort respectively).[77]

Some monolingual Gaelic road signs, particularly direction signs, are used on the Outer Hebrides, where a majority of the population can have a working knowledge of the language. These omit the English translation entirely.

Bilingual railway station signs are now more frequent than they used to be. Practically all the stations in the Highland area use both English and Gaelic, and the use of bilingual station signs has become more frequent in the Lowlands of Scotland, including areas where Gaelic has not been spoken for a long time.[citation needed]

This has been welcomed by many supporters of the language as a means of raising its profile as well as securing its future as a 'living language' (i.e. allowing people to use it to navigate from A to B in place of English) and creating a sense of place. However, in some places, such as Caithness, the Highland Council's intention to introduce bilingual signage has incited controversy.[78]

The Ordnance Survey has acted in recent years to correct many of the mistakes that appear on maps. They announced in 2004 that they intended to correct them and set up a committee to determine the correct forms of Gaelic place names for their maps.[77] Ainmean-Àite na h-Alba ("Place names in Scotland") is the national advisory partnership for Gaelic place names in Scotland.[79]

Canada

[edit]In the nineteenth century, Canadian Gaelic was the third-most widely spoken European language in British North America[80] and Gaelic-speaking immigrant communities could be found throughout what is modern-day Canada. Gaelic poets in Canada produced a significant literary tradition.[81] The number of Gaelic-speaking individuals and communities declined sharply, however, after the First World War.[82]

Nova Scotia

[edit]

At the start of the 21st century, it was estimated that no more than 500 people in Nova Scotia still spoke Scottish Gaelic as a first language. In the 2011 census, 300 people claimed to have Gaelic as their first language (a figure that may include Irish Gaelic).[83] In the same 2011 census, 1,275 people claimed to speak Gaelic, a figure that not only included all Gaelic languages but also those people who are not first language speakers,[84] of whom 300 claim to have Gaelic as their "mother tongue."[85][a]

The Nova Scotia government maintains the Office of Gaelic Affairs (Iomairtean na Gàidhlig), which is dedicated to the development of Scottish Gaelic language, culture and tourism in Nova Scotia, and which estimates about 2,000 total Gaelic speakers to be in the province.[13] As in Scotland, areas of North-Eastern Nova Scotia and Cape Breton have bilingual street signs. Nova Scotia also has Comhairle na Gàidhlig (The Gaelic Council of Nova Scotia), a non-profit society dedicated to the maintenance and promotion of the Gaelic language and culture in Maritime Canada. In 2018, the Nova Scotia government launched a new Gaelic vehicle licence plate to raise awareness of the language and help fund Gaelic language and culture initiatives.[87]

In September 2021, the first Gaelic-medium primary school outside of Scotland, named Taigh Sgoile na Drochaide, opened in Mabou, Nova Scotia.[88]

Outside Nova Scotia

[edit]Maxville Public School in Maxville, Glengarry, Ontario, offers Scottish Gaelic lessons weekly.[89]

In Prince Edward Island, the Colonel Gray High School now offers both an introductory and an advanced course in Gaelic; both language and history are taught in these classes. This is the first recorded time that Gaelic has ever been taught as an official course on Prince Edward Island.[90]

The province of British Columbia is host to the Comunn Gàidhlig Bhancoubhair (The Gaelic Society of Vancouver), the Vancouver Gaelic Choir, the Victoria Gaelic Choir, as well as the annual Gaelic festival Mòd Vancouver. The city of Vancouver's Scottish Cultural Centre also holds seasonal Scottish Gaelic evening classes.[citation needed]

Media

[edit]The BBC operates a Gaelic-language radio station Radio nan Gàidheal as well as a television channel, BBC Alba. Launched on 19 September 2008, BBC Alba is widely available in the UK (on Freeview, Freesat, Sky and Virgin Media). It also broadcasts across Europe on the Astra 2 satellites.[91] The channel is being operated in partnership between BBC Scotland and MG Alba – an organisation funded by the Scottish Government, which works to promote the Gaelic language in broadcasting.[92] The ITV franchise in central Scotland, STV Central, has, in the past, produced a number of Scottish Gaelic programmes for both BBC Alba and its own main channel.[92]

Until BBC Alba was broadcast on Freeview, viewers were able to receive the channel TeleG, which broadcast for an hour every evening. Upon BBC Alba's launch on Freeview, it took the channel number that was previously assigned to TeleG.

There are also television programmes in the language on other BBC channels and on the independent commercial channels, usually subtitled in English. The ITV franchise in the north of Scotland, STV North (formerly Grampian Television) produces some non-news programming in Scottish Gaelic.

Education

[edit]Scotland

[edit]

| Year | Number of students in Gaelic medium education |

Percentage of all students in Scotland |

|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 2,480 | 0.35% |

| 2006 | 2,535 | 0.36%[93] |

| 2007 | 2,601 | 0.38% |

| 2008 | 2,766 | 0.40%[94] |

| 2009 | 2,638 | 0.39%[95] |

| 2010 | 2,647 | 0.39%[96] |

| 2011 | 2,929 | 0.44%[97] |

| 2012 | 2,871 | 0.43%[98] |

| 2013 | 2,953 | 0.44%[99] |

| 2014 | 3,583 | 0.53%[100] |

| 2015 | 3,660 | 0.54%[101] |

| 2016 | 3,892 | 0.57%[102] |

| 2017 | 3,965 | 0.58%[103] |

| 2018 | 4,343 | 0.63%[104] |

| 2019 | 4,631 | 0.66% |

| 2020 | 4,849 | 0.69% |

| 2021 | 5,066 | |

| 2022 | 5,110 | |

| 2023 | 5,461 | [105] |

The Education (Scotland) Act 1872, which completely ignored Gaelic and led to generations of Gaels being forbidden to speak their native language in the classroom is now recognised as having dealt a major blow to the language. People still living in 2001 could recall being beaten for speaking Gaelic in school.[106] Even later, when these attitudes had changed, little provision was made for Gaelic medium education in Scottish schools. As late as 1958, even in Highland schools, only 20% of primary students were taught Gaelic as a subject, and only 5% were taught other subjects through the Gaelic language.[55]

Gaelic-medium playgroups for young children began to appear in Scotland during the late 1970s and early 1980s. Parent enthusiasm may have been a factor in the "establishment of the first Gaelic medium primary school units in Glasgow and Inverness in 1985".[107]

The first modern solely Gaelic-medium secondary school, Sgoil Ghàidhlig Ghlaschu ("Glasgow Gaelic School"), was opened at Woodside in Glasgow in 2006 (61 partially Gaelic-medium primary schools and approximately a dozen Gaelic-medium secondary schools also exist). According to Bòrd na Gàidhlig, a total of 2,092 primary pupils were enrolled in Gaelic-medium primary education in 2008–09, as opposed to 24 in 1985.[108]

The Columba Initiative, also known as colmcille (formerly Iomairt Cholm Cille), is a body that seeks to promote links between speakers of Scottish Gaelic and Irish.

In November 2019, the language-learning app Duolingo opened a beta course in Gaelic.[109][110][111]

Starting from summer 2020, children starting school in the Western Isles will be enrolled in GME (Gaelic-medium education) unless parents request differently. Children will be taught Scottish Gaelic from P1 to P4 and then English will be introduced to give them a bilingual education.[112]

Canada

[edit]In May 2004, the Nova Scotia government announced the funding of an initiative to support the language and its culture within the province. Several public schools in Northeastern Nova Scotia and Cape Breton offer Gaelic classes as part of the high-school curriculum.[113]

Maxville Public School in Maxville, Glengarry, Ontario, offers Scottish Gaelic lessons weekly. In Prince Edward Island, the Colonel Gray High School offer an introductory and an advanced course in Scottish Gaelic.[114]

Higher and further education

[edit]A number of Scottish and some Irish universities offer full-time degrees including a Gaelic language element, usually graduating as Celtic Studies.

In Nova Scotia, Canada, St. Francis Xavier University, the Gaelic College of Celtic Arts and Crafts and Cape Breton University (formerly known as the "University College of Cape Breton") offer Celtic Studies degrees and/or Gaelic language programs. The government's Office of Gaelic Affairs offers lunch-time lessons to public servants in Halifax.

In Russia the Moscow State University offers Gaelic language, history and culture courses.

The University of the Highlands and Islands offers a range of Gaelic language, history and culture courses at the National Certificate, Higher National Diploma, Bachelor of Arts (ordinary), Bachelor of Arts (Honours) and Master of Science levels. It offers opportunities for postgraduate research through the medium of Gaelic. Residential courses at Sabhal Mòr Ostaig on the Isle of Skye offer adults the chance to become fluent in Gaelic in one year. Many continue to complete degrees, or to follow up as distance learners. A number of other colleges offer a one-year certificate course, which is also available online (pending accreditation).

Lews Castle College's Benbecula campus offers an independent 1-year course in Gaelic and Traditional Music (FE, SQF level 5/6).

Church

[edit]

In the Western Isles, the isles of Lewis, Harris and North Uist have a Presbyterian majority (largely Church of Scotland – Eaglais na h-Alba in Gaelic, Free Church of Scotland and Free Presbyterian Church of Scotland). The isles of South Uist and Barra have a Catholic majority. All these churches have Gaelic-speaking congregations throughout the Western Isles. Notable city congregations with regular services in Gaelic are St Columba's Church, Glasgow and Greyfriars Tolbooth & Highland Kirk, Edinburgh. Leabhar Sheirbheisean—a shorter Gaelic version of the English-language Book of Common Order—was published in 1996 by the Church of Scotland.

The widespread use of English in worship has often been suggested as one of the historic reasons for the decline of Gaelic. The Church of Scotland is supportive today,[vague] but has a shortage of Gaelic-speaking ministers. The Free Church also recently announced plans to abolish Gaelic-language communion services, citing both a lack of ministers and a desire to have their congregations united at communion time.[115]

Literature

[edit]From the sixth century to the present day, Scottish Gaelic has been used as a literary language. Two prominent writers of the twentieth century are Anne Frater and Sorley MacLean.

Names

[edit]Personal names

[edit]Gaelic has its own version of European-wide names which also have English forms, for example: Iain (John), Alasdair (Alexander), Uilleam (William), Catrìona (Catherine), Raibeart (Robert), Cairistìona (Christina), Anna (Ann), Màiri (Mary), Seumas (James), Pàdraig (Patrick) and Tòmas (Thomas). Not all traditional Gaelic names have direct equivalents in English: Oighrig, which is normally rendered as Euphemia (Effie) or Henrietta (Etta) (formerly also as Henny or even as Harriet), or, Diorbhal, which is "matched" with Dorothy, simply on the basis of a certain similarity in spelling. Many of these traditional Gaelic-only names are now regarded as old-fashioned, and hence are rarely or never used.

Some names have come into Gaelic from Old Norse; for example, Somhairle ( < Somarliðr), Tormod (< Þórmóðr), Raghnall or Raonull (< Rǫgnvaldr), Torcuil (< Þórkell, Þórketill), Ìomhar (Ívarr). These are conventionally rendered in English as Sorley (or, historically, Somerled), Norman, Ronald or Ranald, Torquil and Iver (or Evander).

Some Scottish names are Anglicized forms of Gaelic names: Aonghas → (Angus), Dòmhnall→ (Donald), for instance. Hamish, and the recently established Mhairi (pronounced [vaːri]) come from the Gaelic for, respectively, James, and Mary, but derive from the form of the names as they appear in the vocative case: Seumas (James) (nom.) → Sheumais (voc.) and Màiri (Mary) (nom.) → Mhàiri (voc.).

Surnames

[edit]The most common class of Gaelic surnames are those beginning with mac (Gaelic for "son"), such as MacGillEathain / MacIllEathain[116][117] (MacLean). The female form is nic (Gaelic for "daughter"), so Catherine MacPhee is properly called in Gaelic, Catrìona Nic a' Phì[118] (strictly, nic is a contraction of the Gaelic phrase nighean mhic, meaning "daughter of the son", thus NicDhòmhnaill[117] really means "daughter of MacDonald" rather than "daughter of Donald"). The "of" part actually comes from the genitive form of the patronymic that follows the prefix; in the case of MacDhòmhnaill, Dhòmhnaill ("of Donald") is the genitive form of Dòmhnall ("Donald").[119]

Several colours give rise to common Scottish surnames: bàn (Bain – white), ruadh (Roy – red), dubh (Dow, Duff – black), donn (Dunn – brown), buidhe (Bowie – yellow) although in Gaelic these occur as part of a fuller form such as MacGille 'son of the servant of', i.e. MacGilleBhàin, MacGilleRuaidh, MacGilleDhuibh, MacGilleDhuinn, MacGilleBhuidhe.

Phonology

[edit]Most varieties of Gaelic show either eight or nine vowel qualities (/i e ɛ a ɔ o u ɤ ɯ/) in their inventory of vowel phonemes, which can be either long or short. There are also two reduced vowels ([ə ɪ]) which occur only in their short versions. Although some vowels are strongly nasal, instances of distinctive nasality are rare. There are about nine diphthongs and a few triphthongs.

Most consonants have both palatal and non-palatal counterparts, including a very rich system of liquids, nasals and trills (i.e. three contrasting "l" sounds, three contrasting "n" sounds and three contrasting "r" sounds). The historically voiced stops [b d̪ ɡ] have lost their voicing, so the phonemic contrast today is between unaspirated [p t̪ k] and aspirated [pʰ t̪ʰ kʰ]. In many dialects, these stops may however gain voicing through secondary articulation through a preceding nasal, for examples doras [t̪ɔɾəs̪] "door" but an doras "the door" as [ən̪ˠ d̪ɔɾəs̪] or [ə n̪ˠɔɾəs̪].

In some fixed phrases, these changes are shown permanently, as the link with the base words has been lost, as in an-dràsta "now", from an tràth-sa "this time/period".

In medial and final position, the aspirated stops are preaspirated rather than postaspirated.

Orthography

[edit]Scottish Gaelic orthography is fairly regular; its standard was set by the 1767 New Testament. The 1981 Scottish Examination Board recommendations for Scottish Gaelic, the Gaelic Orthographic Conventions, were adopted by most publishers and agencies, although they remain controversial among some academics, most notably Ronald Black.[120]

The quality of consonants (broad or slender) is indicated by the vowels surrounding them. Slender (palatalised) consonants are surrounded by slender vowels (⟨e, i⟩), while broad (neutral or velarised) consonants are surrounded by broad vowels (⟨a, o, u⟩). The spelling rule known as caol ri caol agus leathann ri leathann ("slender to slender and broad to broad") requires that a word-medial consonant or consonant group followed by ⟨i, e⟩ is preceded by ⟨i, e⟩ and similarly, if followed by ⟨a, o, u⟩ is preceded by ⟨a, o, u⟩.

This rule sometimes leads to the insertion of a silent written vowel. For example, plurals in Gaelic are often formed with the suffix -an [ən], for example, bròg [prɔːk] ("shoe") / brògan [prɔːkən] ("shoes"). But because of the spelling rule, the suffix is spelled -⟨ean⟩ (but pronounced the same, [ən]) after a slender consonant, as in muinntir [mɯi̯ɲtʲɪrʲ] ("[a] people") / muinntirean [mɯi̯ɲtʲɪrʲən] ("peoples") where ⟨e⟩ is purely a graphic vowel inserted to conform with the spelling rule because ⟨i⟩ precedes the ⟨r⟩.

Unstressed vowels omitted in speech can be omitted in informal writing, e.g. Tha mi an dòchas. ("I hope.") > Tha mi 'n dòchas.

Scots English orthographic rules have also been used at various times in Gaelic writing. Notable examples of Gaelic verse composed in this manner are the Book of the Dean of Lismore and the Fernaig manuscript.

Alphabet

[edit]

Ogham

[edit]The Ogham writing system was used in Ireland to write Primitive Irish and Old Irish until it was supplanted by the Latin script in the 5th century CE in Ireland.[121] In Scotland, the majority of Ogham inscriptions are in Pictish but a number of Goidelic Ogham inscriptions also exist, such as the Giogha Stone which bears the inscription VICULA MAQ CUGINI 'Viqula, son of Comginus',[122] with Goidelic MAQ (modern mac 'son') rather than Brythonic MAB (cf. modern Welsh mab 'son').

Insular script

[edit]

The Insular script was used both in Ireland and Scotland but had largely disappeared in Scotland by the 16th century. It consisted of the same 18 letters still in modern use ⟨a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i, l, m, n, o, p, r, s, t, u⟩.[123][124] and generally did not contain ⟨j, k, q, v, w, x, y, z⟩.

In addition to the base letters, vowels in the Insular script could be accented with an acute accent (⟨á, é, í, ó, ú⟩ to indicate length. The overdot was used to indicate lenition of ⟨ḟ, ṡ⟩, while the following ⟨h⟩ was used for ⟨ch, ph, th⟩. The lenition of other letters was not generally indicated initially but eventually the two methods were used in parallel to represent the lenition of any consonant and competed with each other until the standard practice became to use the overdot in the Insular Script and the following ⟨h⟩ in Roman type, i.e. ⟨ḃ, ċ, ḋ, ḟ, ġ, ṁ, ṗ, ṡ, ṫ⟩ are equivalent to ⟨bh, ch, dh, fh, gh, mh, ph, sh, th⟩. The use of Gaelic type and the overdot today is restricted to decorative usages.

Letters with an overdot have been available since Unicode 5.0 .[125]

Latin script

[edit]The modern Scottish Gaelic alphabet has 18 letters: ⟨a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i, l, m, n, o, p, r, s, t, u⟩. ⟨h⟩ is mostly used to indicate lenition of a consonant. The letters of the alphabet were traditionally named after trees, but this custom has fallen out of use.

Long vowels are marked with a grave accent (⟨à, è, ì, ò, ù⟩), indicated through digraphs (e.g. ⟨ao⟩ for [ɯː]) or conditioned by certain consonant environments (e.g. ⟨u⟩ preceding a non-intervocalic ⟨nn⟩ is [uː]). Traditionally the acute accent was used on ⟨á, é, ó⟩ to represent long close-mid vowels, but the spelling reforms replaced it with the grave accent.[117]

Certain 18th century sources used only an acute accent along the lines of Irish, such as in the writings of Alasdair mac Mhaighstir Alasdair (1741–51) and the earliest editions (1768–90) of Duncan Ban MacIntyre.[126]

Grammar

[edit]Scottish Gaelic is an Indo-European language with an inflecting morphology, verb–subject–object word order and two grammatical genders.

Noun inflection

[edit]Gaelic nouns inflect for four cases (nominative/accusative, vocative, genitive and dative) and three numbers (singular, dual and plural).

They are also normally classed as either masculine or feminine. A small number of words that used to belong to the neuter class show some degree of gender confusion. For example, in some dialects am muir "the sea" behaves as a masculine noun in the nominative case, but as a feminine noun in the genitive (na mara).

Nouns are marked for case in a number of ways, most commonly involving various combinations of lenition, palatalisation and suffixation.

Verb inflection

[edit]There are 12 irregular verbs.[127] Most other verbs follow a fully predictable paradigm, although polysyllabic verbs ending in laterals can deviate from this paradigm as they show syncopation.

There are:

- Three persons: 1st, 2nd and 3rd

- Two numbers: singular and plural

- Two voices: traditionally called active and passive, but actually personal and impersonal

- Three non-composed combined TAM forms expressing tense, aspect and mood, i.e. non-past (future-habitual), conditional (future of the past), and past (preterite); several composed TAM forms, such as pluperfect, future perfect, present perfect, present continuous, past continuous, conditional perfect, etc. Two verbs, bi, used to attribute a notionally temporary state, action, or quality to the subject, and is (a defective verb that has only two forms), used to show a notional permanent identity or quality, have non-composed present and non-past tense forms: (bi) tha [perfective present], bidh/bithidh [imperfective non-past][117] and all other expected verb forms, though the verb adjective ("past participle") is lacking; (is) is, bu past and conditional.

- Four moods: independent (used in affirmative main clause verbs), relative (used in verbs in affirmative relative clauses), dependent (used in subordinate clauses, anti-affirmative relative clauses, and anti-affirmative main clauses), and subjunctive.

Word order

[edit]Word order is strictly verb–subject–object, including questions, negative questions and negatives. Only a restricted set of preverb particles may occur before the verb.

Lexicon

[edit]The majority of the vocabulary of Scottish Gaelic is of Celtic origin. However, Gaelic contains substantially more words of non-Goidelic extraction than Irish. The main sources of loanwords into Gaelic are the Germanic languages English, Scots and Norse. Other sources include Latin, French and the Brittonic languages.[128]

Many direct Latin loanwords in Scottish Gaelic were adopted during the Old and Middle Irish (600–1200 CE) stages of the language and are often terms related to Christianity. Latin is also the source of the days of the week Diluain ("Monday"), Dimàirt (Tuesday), Disathairne ("Saturday") and Didòmhnaich ("Sunday").[128]

Brittonic

[edit]The Brittonic languages Cumbric and Pictish were spoken in Scotland during the Early to High Middle Ages, and Scottish Gaelic has many Brittonic influences. Scottish Gaelic contains a number of apparently P-Celtic loanwords, but it is not always possible to disentangle P and Q Celtic words. However, some common words such as dìleab ("legacy"), monadh (mynydd; "mountain") and preas (prys; "bush") are transparently Brittonic in origin.[25]

Scottish Gaelic contains a number of words, principally toponymic elements, that are sometimes more closely aligned in their usage and sense with their Brittonic cognates than with their Irish. This is indicative of the operation of a Brittonic substrate influence. Such items include:[129][130]

| Gaelic | Meaning | Brittonic | Meaning | Irish | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lios | palace (in place-names) | llys | palace, court | les (Old Irish) | land between a house and its enclosure |

| srath | river-valley | ystrad (Welsh) | river-valley | srath | grassland |

| tom | thicket, knoll, mound | tom/tomen (Welsh) | dung, mound | tom | shrub |

Neologisms

[edit]In common with other Indo-European languages, the neologisms coined for modern concepts are typically based on Greek or Latin, although often coming through English; television, for instance, becomes telebhisean and computer becomes coimpiùtar. Some speakers use an English word even if there is a Gaelic equivalent, applying the rules of Gaelic grammar. With verbs, for instance, they will simply add the verbal suffix (-eadh, or, in Lewis, -igeadh, as in, "Tha mi a' watch eadh (Lewis, "watch igeadh") an telly" (I am watching the television), instead of "Tha mi a' coimhead air an telebhisean". This phenomenon was described over 170 years ago, by the minister who compiled the account covering the parish of Stornoway in the New Statistical Account of Scotland, and examples can be found dating to the eighteenth century.[131] However, as Gaelic medium education grows in popularity, a newer generation of literate Gaels has become more familiar with modern Gaelic vocabulary.[citation needed]

Loanwords into other languages

[edit]Scottish Gaelic has also influenced the Scots language and English, particularly Scottish Standard English. Loanwords include: whisky, slogan, brogue, jilt, clan, galore, trousers, gob, as well as familiar elements of Scottish geography like ben (beinn), glen (gleann) and loch. Irish has also influenced Lowland Scots and English in Scotland, but it is not always easy to distinguish its influence from that of Scottish Gaelic.[128][page needed]

Common words and phrases with Irish and Manx equivalents

[edit]| Scottish Gaelic | Irish | Manx Gaelic | English |

|---|---|---|---|

| sinn [ʃiɲ] | (South) sinn [ʃɪn̠ʲ] (West/North) muid [mˠɪdʲ] |

shin [ʃin] | we |

| aon [ɯːn] | aon (South) [eːnˠ] (North/West) [iːnˠ] (older North) [ɯːnˠ] | nane [neːn] (un [œn]) |

one |

| mòr [moːɾ] | mór (North/West) [mˠoːɾˠ] (South) [mˠuəɾˠ] | mooar [muːɾ] | big |

| iasg [iəs̪k] | iasc [iəsˠk] | eeast [jiːs(t)] | fish |

| cù [kʰuː] (madadh [mat̪əɣ], gadhar [gə(ɣ)ər]) |

madadh (North) [mˠad̪ˠu] (West) [mˠad̪ˠə] (South)madra [mˠad̪ˠɾˠə] gadhar (South/West) [ɡəiɾˠ] (North) [ɡeːɾˠ] (cú [kuː] "hound") |

moddey [mɔːðə] (coo [kʰuː] hound) |

dog |

| grian [kɾʲiən] | grian [ɟɾʲiənˠ] | grian [ɡriᵈn] | sun |

| craobh [kʰɾɯːv] (crann [kʰɾaun̪ˠ] mast) |

crann (North) [kɾan̪ˠ] (West) [kɾɑːn̪ˠ] (South) [kɾaun̪ˠ] (craobh "branch" (North/West) [kɾˠiːw, -ɯːw] (South) [kɾˠeːv]) |

billey [biʎə] | tree |

| cadal [kʰat̪əl̪ˠ] | codladh (South) [ˈkɔl̪ˠə] (North) [ˈkɔl̪ˠu](codail "to sleep" [kɔdəlʲ]) | cadley [kʲadlə] | sleep (verbal noun) |

| ceann (North) [kʰʲaun̪ˠ] (South) [kʰʲɛun̪ˠ] | ceann (North) [can̪ˠ] (West) [cɑːn̪ˠ] (South) [caun̪ˠ] | kione (South) [kʲoᵈn̪ˠ] (north) [kʲaun̪] | head |

| cha do dh'òl thu [xa t̪ə ɣɔːl̪ˠ u] | níor ól tú [n̠ʲiːɾˠ oːl̪ˠ t̪ˠuː](North) char ól tú [xaɾˠ ɔːl̪ˠ t̪ˠuː] | cha diu oo [xa dju u] | you did not drink |

| bha mi a' faicinn [va mi (ə) fɛçkʲɪɲ] | bhí mé ag feiceáil [vʲiː mʲeː (ə(ɡ)) fʲɛcaːlʲ] (Munster) bhí mé/bhíos ag feiscint [vʲiː mʲeː/vʲiːsˠ (ə(ɡ)) fʲɪʃcintʲ] |

va mee fakin [væ mə faːɣin] | (Scotland, Man) I saw, I was seeing (Ireland) I was seeing |

| slàinte [s̪l̪ˠaːɲtʲə] | sláinte [sˠl̪ˠaːn̠ʲtʲə] | slaynt [s̪l̪ˠaːɲtʃ] | health; cheers! (toast) |

Note: Items in brackets denote archaic, dialectal or regional variant forms

Sample text

[edit]Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in Scottish Gaelic:

- Rugadh na h-uile duine saor agus co-ionnan nan urram 's nan còirichean. Tha iad reusanta is cogaiseach, agus bu chòir dhaibh a ghiùlain ris a chèile ann an spiorad bràthaireil.[132]

Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in English:

- All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.[133]

References

[edit]Explanatory notes

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b "Scotland's Census 2022 - Ethnic group, national identity, language and religion".

- ^ Statistics Canada, Nova Scotia (Code 12) (table), National Household Survey (NHS) Profile, 2011 NHS, Catalogue No. 99‑004‑XWE (Ottawa: 2013‑06‑26)

- ^ Moseley, Christopher; Nicolas, Alexander, eds. (2010). Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger (PDF) (3rd ed.). Paris: UNESCO. ISBN 978-92-3-104096-2. Archived from the original on 23 July 2022.

- ^ "Background on the Irish Language". Údarás na Gaeltachta. Archived from the original on 24 December 2019.

- ^ MacAulay, Donald (1992). The Celtic Languages. Cambridge University Press. p. 144.

- ^ Kavanagh, Paul (12 March 2011). "Scotland's Language Myths: 4. Gaelic has nothing to do with the Lowlands". Newsnet.scot. Archived from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- ^ "Gaelic History / Highland Council Gaelic Toolkit / The Highland Council / Welcome to Northern Potential". HighlandLife. Archived from the original on 19 June 2021. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- ^ "Census shows decline in Gaelic speakers 'slowed'". BBC News. 26 September 2013. Archived from the original on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- ^ "Scotland's Census 2022 - Ethnic group, national identity, language and religion". Scotland's Census. Archived from the original on 22 June 2024. Retrieved 21 May 2024.

- ^ "Home". Scotland's Census. Archived from the original on 22 June 2024. Retrieved 21 May 2024.

- ^ "Census Profile, 2016 Census". 2016 Census. Statistics Canada. 8 February 2017. Archived from the original on 15 May 2021. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- ^ "Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population". 2021 Census. Statistics Canada. 9 February 2022. Archived from the original on 26 September 2023. Retrieved 10 October 2023.

- ^ a b "Nova Scotia/Alba Nuadh". Province of Nova Scotia Gaelic Affairs. Archived from the original on 23 April 2020. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- ^ "Gaelic". The Scottish Government. Archived from the original on 4 January 2018. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ "Scottish Languages Bill passed". Scottish Parliament. Retrieved 18 June 2025.

- ^ "Definition of Gaelic in English by Oxford Dictionaries". Oxford Dictionaries. Archived from the original on 18 August 2018. Retrieved 5 August 2018.

- ^ Horsbroch, Dauvit. "1350–1450 Early Scots". Scots Language Centre. Archived from the original on 26 August 2020. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- ^ Transactions of the Philological Society Archived 16 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine, 1872, page 50

- ^ McMahon, Sean (2012). Brewer's dictionary of Irish phrase & fable. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. p. 276. ISBN 9781849725927.

- ^ Jones, Charles (1997). The Edinburgh history of the Scots language. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-0754-9.

- ^ Chadwick, Nora Kershaw; Dyllon, Myles (1972). The Celtic Realms. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-7607-4284-6.

- ^ Campbell, Ewan (2001). "Were the Scots Irish?". Antiquity. 75 (288): 285–292. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00060920. S2CID 159844564. Archived from the original on 10 November 2012. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- ^ '... and they won land among the Picts by friendly treaty or the sword' Archived 14 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine. By Cormac McSparron and Brian Williams. Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 141, 145–158

- ^ Broun, "Dunkeld", Broun, "National Identity", Forsyth, "Scotland to 1100", pp. 28–32, Woolf, "Constantine II"; cf. Bannerman, "Scottish Takeover", passim, representing the "traditional" view.

- ^ a b Jackson, Kenneth (1983). "'Loanwords, British and Pictish'". In Thomson, D.S. (ed.). The Companion to Gaelic Scotland. pp. 151–152.

- ^ Green, D. (1983). "'Gaelic: syntax, similarities with British syntax'". In Thomson, D.S. (ed.). The Companion to Gaelic Scotland. pp. 107–108.

- ^ Taylor, S. (2010). "Pictish Placenames Revisited'". In Driscoll, S. (ed.). Pictish Progress: New Studies on Northern Britain in the Middle Ages. pp. 67–119.

- ^ a b c d Withers, Charles W. J. (1984). Gaelic in Scotland, 1698–1981. Edinburgh: John Donald Publishers Ltd. ISBN 978-0859760973.

- ^ Dunshea, Philip M. (1 October 2013). "Druim Alban, Dorsum Britanniae– 'the Spine of Britain'". Scottish Historical Review. 92 (2): 275–289. doi:10.3366/shr.2013.0178.

- ^ Clarkson, Tim (2011). The Makers of Scotland: Picts, Romans, Gaels, and Vikings. Edinburgh: Birlinn Ltd. ISBN 978-1906566296.

- ^ a b Ó Baoill, Colm. "The Scots–Gaelic interface", in Charles Jones, ed., The Edinburgh History of the Scots Language. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1997

- ^ Moray Watson (30 June 2010). Edinburgh Companion to the Gaelic Language. Edinburgh University Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-7486-3710-2.

- ^ Withers, Charles W. J. (1988). "The Geographical History of Gaelic in Scotland". In Colin H. Williams (ed.). Language in Geographic Context.

- ^ a b c d Devine, T. M. (1994). Clanship to Crofters' War: The social transformation of the Scottish Highlands (2013 ed.). Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-9076-9.

- ^ Hunter, James (1976). The Making of the Crofting Community. Donald. ISBN 9780859760140.

- ^ Mackenzie, Donald W. (1990–92). "The Worthy Translator: How the Scottish Gaels got the Scriptures in their own Tongue". Transactions of the Gaelic Society of Inverness. 57.

- ^ a b Campsie, Alison (20 December 2022). "The decade when Scotland lost half its Gaelic speaking people". The Scotsman. Archived from the original on 20 December 2022. Retrieved 20 December 2022.

- ^ "The Gaelic Story at the University of Glasgow". Archived from the original on 24 November 2021. Retrieved 11 August 2019.

- ^ Ó Baoill, Colm (2000). "The Gaelic Continuum". Éigse. 32: 121–134.

- ^ Kennedy, Michael (2002). Gaelic in Nova Scotia: An Economic, Cultural and Social Impact Study (PDF). Province of Nova Scotia. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- ^ Moseley, Christopher (2008). Encyclopedia of the World's Endangered Languages. doi:10.4324/9780203645659. ISBN 9781135796419. Archived from the original on 26 January 2020. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- ^ "Scottish Gaelic". Endangered Languages Project. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- ^ Ross, John (19 February 2009). "'Endangered' Gaelic on map of world's dead languages". The Scotsman. Archived from the original on 25 October 2017. Retrieved 25 October 2017.

- ^ MacAulay, Donald (1992). The Celtic Languages. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521231275. Archived from the original on 17 November 2023. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- ^ "Scotland's Census at a glance: Languages". Scotland's Census. Retrieved 7 June 2024.

- ^ "2011: Gaelic report (part 1)" (PDF). Scotland's Census. Retrieved 7 June 2024.

- ^ "Scotland's Census 2022 - UV212 - Main language (7 categories) by age (6 categories)". UK Data Service. Retrieved 23 July 2025.

- ^ "Scotland's Census 2022 - UV208b - Gaelic language skills (7 categories) by age (6 categories)". UK Data Service. Retrieved 23 July 2025.

- ^ 2011 Census of Scotland Archived 4 June 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Table QS211SC. Viewed 23 June 2014.

- ^ Scotland's Census Results Online (SCROL), Table UV12. Viewed 23 June 2014.

- ^ "Census shows decline in Gaelic speakers 'slowed'". BBC News Online. 26 September 2013. Archived from the original on 5 July 2014. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ^ "Census shows Gaelic declining in its heartlands". BBC News Online. 15 November 2013. Archived from the original on 5 July 2014. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ^ "Ethnic group, national identity, language and religion". Scotland's Census. 29 August 2025. Retrieved 21 September 2025.

- ^ "Pupil Census Supplementary Data". The Scottish Government. 7 December 2011. Archived from the original on 9 July 2019. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- ^ a b O'Hanlon, Fiona (2012). Lost in transition? Celtic language revitalization in Scotland and Wales: the primary to secondary school stage (Thesis). The University of Edinburgh.

- ^ a b McEwan-Fujita, Emily (2 March 2022). "9. Sociolinguistic Ethnography of Gaelic Communities". The Edinburgh Companion to the Gaelic Language. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 172–217. doi:10.1515/9780748637102-013. ISBN 978-0-7486-3710-2. Archived from the original on 19 December 2022. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- ^ a b c Mcewan-Fujita, Emily (1 January 2005). "Neoliberalism and Minority-Language Planning in the Highlands and Islands of Scotland". International Journal of the Sociology of Language (171): 155–171. doi:10.1515/ijsl.2005.2005.171.155. ISSN 1613-3668. S2CID 144370832. Archived from the original on 19 December 2022. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- ^ "Dachaigh – Sabhal Mòr Ostaig". www.smo.uhi.ac.uk (in Scottish Gaelic). Archived from the original on 19 December 2022. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- ^ a b c d e McEWAN-FUJITA, Emily (15 January 2010). "Ideology, affect, and socialization in language shift and revitalization: The experiences of adults learning Gaelic in the Western Isles of Scotland". Language in Society. 39 (1): 27–64. doi:10.1017/S0047404509990649. ISSN 0047-4045. S2CID 145694600.

- ^ a b c Ó Giollagáin, Conchúr (2020). The Gaelic crisis in the vernacular community : a comprehensive sociolinguistic survey of Scottish Gaelic. Gòrdan Camshron, Pàdruig Moireach, Brian Ó Curnáin, Iain Caimbeul, Brian MacDonald, Tamás Péterváry. Aberdeen, Scotland: Aberdeen University Press. doi:10.57132/mpub.14497417. ISBN 978-1-85752-080-4. OCLC 1144113424. Archived from the original on 17 November 2023. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- ^ Prebble, John (1969). The Highland Clearances. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin. ISBN 0140028374.

- ^ a b McEwan-Fujita, Emily (1 January 2011). "Language revitalization discourses as metaculture: Gaelic in Scotland from the 18th to 20th centuries". Language & Communication. 31 (1): 48–62. doi:10.1016/j.langcom.2010.12.001. ISSN 0271-5309. Archived from the original on 8 March 2013. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- ^ Dorian, Nancy C. (5 January 2011). "Reversing Language Shift: The Social Identity and Role of Scottish Gaelic Learners (Belfast Studies in Language, Culture and Politics) by Alasdair MacCaluim". Journal of Sociolinguistics. 13 (2): 266–269. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9841.2009.00407_2.x. Archived from the original on 19 December 2022. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- ^ "SuperWEB2(tm) - Log in". www.scotlandscensus.gov.uk. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ See Kenneth MacKinnon (1991) Gaelic: A Past and Future Prospect. Edinburgh: The Saltire Society.

- ^ "Gaelic Language (Scotland) Act 2005". www.legislation.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 5 July 2007.

- ^ a b "CHAPTER II – CORE COMMITMENTS". www.gov.scot. Archived from the original on 15 November 2022. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- ^ Williams, Colin H., Legislative Devolution and Language Regulation in the United Kingdom, Cardiff University

- ^ "Latest News – SHRC". Scottish Human Rights Commission. 12 October 2008. Archived from the original on 8 April 2011. Retrieved 13 November 2013.

- ^ "UK Ratification of the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. Working Paper 10 – R.Dunbar, 2003" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- ^ "Official Status for Gaelic: Prospects and Problems". 1997. Archived from the original on 1 March 2012.

- ^ Scottish Qualifications Authority, Resource Management. "Gàidhlig". www.sqa.org.uk. SQA. Archived from the original on 25 April 2017. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- ^ Scottish Qualifications Authority, Resource Management. "Gaelic (learners)". www.sqa.org.uk. SQA. Archived from the original on 25 April 2017. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- ^ "An Comunn Gàidhealach – Royal National Mod : Royal National Mod". www.ancomunn.co.uk. Archived from the original on 27 June 2017. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- ^ "EU green light for Scots Gaelic". BBC News. 7 October 2009. Archived from the original on 23 June 2024. Retrieved 23 June 2024.

- ^ "EU green light for Scots Gaelic". BBC News Online. 7 October 2009. Archived from the original on 17 November 2023. Retrieved 7 October 2009.

- ^ a b "Guide to the Gaelic Origins of Place Names in Britain" (PDF). North-harris.org. November 2005. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 July 2021. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

- ^ "Caithness councillors harden resolve against Gaelic signs". The Press and Journal. 24 October 2008. Archived from the original on 20 June 2012. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- ^ "Ainmean-Àite na h-Alba – Gaelic Place-Names of Scotland – About Us". www.ainmean-aite.org. Archived from the original on 25 April 2017. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- ^ Bumstead, J.M (2006). "Scots". Multicultural Canada. Archived from the original on 26 December 2012. Retrieved 30 August 2006.

By 1850 Gaelic was the third most commonly spoken European language in British North America. It was spoken by as many as 200,000 British North Americans of both Scottish and Irish origin as either a first or a second language.

- ^ Newton, Michael (2015). Seanchaidh na Coille / Memory-Keeper of the Forest: Anthology of Scottish Gaelic Literature of Canada. Cape Breton University Press. ISBN 978-1-77206-016-4.

- ^ Jonathan Dembling, "Gaelic in Canada: New Evidence from an Old Census Archived 21 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine", Paper read at the 3rd biannual Rannsachadh na Gàidhlig, University of Edinburgh, 21–23 July 2004, in: Cànan & Cultar / Language & Culture: Rannsachadh na Gàidhlig 3, edited by Wilson MacLeod, James E. Fraser & Anja Gunderloch (Edinburgh: Dunedin Academic Press, 2006), pp. 203–214, ISBN 978-1903765-60-9.

- ^ Kennedy, Michael (2002). "Gaelic Nova Scotia – An Economic, Cultural, and Social Impact Study" (PDF). Nova Scotia Museum. pp. 114–115. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- ^ Statistics Canada, Nova Scotia (Code 12) Archived 23 April 2020 at the Wayback Machine (table), National Household Survey (NHS) Profile, 2011 NHS, Catalogue № 99-004-XWE (Ottawa: September 11, 2013).

- ^ Patten, Melanie (29 February 2016). "Rebirth of a 'sleeping' language: How N.S. is reviving its Gaelic culture". Atlantic. Archived from the original on 13 July 2018. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- ^ "National Household Survey Profile, Nova Scotia, 2011". Statistics Canada. 8 May 2013. Archived from the original on 13 May 2014. Retrieved 15 August 2014.

- ^ "Nova Scotia unveils Gaelic licence plate, as it seeks to expand language". Atlantic CTV News. Bell Media. The Canadian Press. 1 May 2018. Archived from the original on 16 August 2021. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ "Gaelic Medium Education in Nova Scotia". Bòrd na Gàidhlig. 8 September 2021. Archived from the original on 8 September 2021. Retrieved 8 September 2021.

- ^ International, Radio Canada (28 January 2015). "Gaelic language slowly gaining ground in Canada". RCI | English. Archived from the original on 9 June 2020. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- ^ "Gaelic language slowly gaining ground in Canada". Radio Canada International. 28 January 2015. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ BBC Reception advice – BBC Online

- ^ a b About BBC Alba Archived 17 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine, from BBC Online

- ^ Pupils in Scotland, 2006 Archived 1 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine from scot.gov.uk. Published February 2007, Scottish Government.

- ^ Pupils in Scotland, 2008 Archived 7 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine from scot.gov.uk. Published February 2009, Scottish Government.

- ^ Pupils in Scotland, 2009 Archived 7 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine from scotland.gov.uk. Published 27 November 2009, Scottish Government.

- ^ "Scottish Government: Pupils Census, Supplementary Data". Scotland.gov.uk. 14 June 2011. Archived from the original on 21 November 2011. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- ^ Pupil Census, Supplementary data 2011 Archived 27 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine Spreadsheet published 3 February 2012 (Table 1.13)

- ^ Pupil Census, Supplementary data 2012 Archived 27 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine Spreadsheet published 11 December 2012 (Table 1.13)

- ^ Pupil Census, Supplementary data 2013 Archived 27 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine Spreadsheet (Table 1.13)

- ^ Pupil Census, Supplementary data 2014 Archived 27 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine Spreadsheet (Table 1.13)

- ^ Pupil Census, Supplementary data 2015 Archived 1 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine Spreadsheet (Table 1.13)

- ^ Pupil Census, Supplementary data 2016 Archived 14 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine Spreadsheet (Table 1.13)

- ^ Pupil Census, Supplementary data 2017 Archived 17 May 2018 at the Wayback Machine Spreadsheet (Table 1.13)

- ^ Pupil Census, Supplementary data 2018 Archived 4 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine Spreadsheet (Table 1.13)

- ^ Number of primary and high school students taught using the Gaelic language in Scotland from 2018 to 2023

- ^ Pagoeta, Mikel Morris (2001). Europe Phrasebook. Lonely Planet. p. 416. ISBN 978-1-86450-224-4.

- ^ O'Hanlon, Fiona (2012). Lost in transition? Celtic language revitalization in Scotland and Wales: the primary to secondary school stage (Thesis). The University of Edinburgh. p. 48.

- ^ "Gael-force wind of change in the classroom". The Scotsman. 29 October 2008. Archived from the original on 30 October 2008. Retrieved 8 June 2011.

- ^ "Thousands sign up for new online Gaelic course". BBC News. 28 November 2019. Archived from the original on 30 November 2019. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- ^ "Scottish Gaelic course on Duolingo app has 20,000 signups ahead of launch". www.scotsman.com. 28 November 2019. Archived from the original on 29 November 2019. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- ^ Dingwall, Blair (28 November 2019). "Tens of thousands sign up in matter of hours as Duolingo releases Scottish Gaelic course". Archived from the original on 29 November 2019. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- ^ "Gaelic to be 'default' in Western Isles schools". BBC News. 23 January 2020. Archived from the original on 24 January 2020. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- ^ "Gaelic core class increasingly popular in Nova Scotia". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. 26 January 2015. Archived from the original on 15 November 2015. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- ^ International, Radio Canada (28 January 2015). "Gaelic language slowly gaining ground in Canada". RCI | English. Archived from the original on 23 June 2017. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- ^ MacLeod, Murdo (6 January 2008). "Free Church plans to scrap Gaelic communion service". The Scotsman. Edinburgh. Archived from the original on 11 January 2009. Retrieved 19 January 2008.

- ^ "Alba air Taghadh – beò à Inbhir Nis". BBC Radio nan Gàidheal. Archived from the original on 3 November 2018. Retrieved 19 January 2017.

- ^ a b c d "Gaelic Orthographic Conventions" (PDF). Bòrd na Gàidhlig. October 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 January 2017. Retrieved 19 January 2017.