Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Homophone

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Linguistics |

|---|

|

|

A homophone (/ˈhɒməfoʊn, ˈhoʊmə-/)[a] is a word that is pronounced the same as another word but differs in meaning or in spelling. The two words may be spelled the same, for example rose (flower) and rose (past tense of "rise"), or spelled differently, as in rain, reign, and rein. The term homophone sometimes applies to units longer or shorter than words, for example a phrase, letter, or groups of letters which are pronounced the same as a counterpart. Any unit with this property is said to be homophonous (/həˈmɒfənəs/).

Homophones that are spelled the same are both homographs and homonyms. For example, the word read, in "He is well read" and in "Yesterday, I read that book".[b]

Homophones that are spelled differently are also called heterographs, e.g. to, too, and two.

Wordplay and games

[edit]Homophones are often used to create puns and to deceive the reader (as in crossword puzzles) or to suggest multiple meanings. The last usage is common in poetry and creative literature. An example of this is seen in Dylan Thomas's radio play Under Milk Wood: "The shops in mourning" where mourning can be heard as mourning or morning. Another vivid example is Thomas Hood's use of birth and berth as well as told and toll'd (tolled) in his poem "Faithless Sally Brown":

- His death, which happen'd in his berth,

- At forty-odd befell:

- They went and told the sexton, and

- The sexton toll'd the bell.

In some accents, various sounds have merged in that they are no longer distinctive, and thus words that differ only by those sounds in an accent that maintains the distinction (a minimal pair) are homophonous in the accent with the merger. Some examples from English are:

- pin and pen in many southern American accents

- by and buy

- merry, marry, and Mary in most American accents

- The pairs do and due as well as forward and foreword are homophonous in most American accents but not in most English accents

- The pairs talk and torque as well as court and caught are distinguished in rhotic accents, such as Scottish English, and most dialects of American English, but are homophones in some non-rhotic accents, such as British Received Pronunciation

Wordplay is particularly common in English because the multiplicity of linguistic influences offers considerable complication in spelling and meaning and pronunciation compared with other languages.

Malapropisms, which often create a similar comic effect, are usually near-homophones. See also Eggcorn.

Same-sounding phrases

[edit]During the 1980s, an attempt was made to promote a distinctive term for same-sounding multiple words or phrases, by referring to them as "oronyms",[c] but since the term oronym was already well established in linguistics as an onomastic designation for a class of toponymic features (names of mountains, hills, etc.),[2] the alternative use of the same term was not well-accepted in scholarly literature.[3]

In various languages

[edit]English

[edit]There are online lists of multinyms. In English, concerning groups of homophones (excluding proper nouns), there are approximately 88 triplets, 24 quadruplets, 2 quintuplets, 1 sextet, 1 septet, and 1 octet. The octet is:

- raise, rays, rase, raze, rehs, réis, reais, res

Other than the common words raise and rays, this octet includes

- raze – a verb meaning "to demolish, level to the ground" or "to scrape as if with a razor"

- rase – an archaic verb meaning "to erase"

- rehs – the plural of reh, a mixture of sodium salts found as an efflorescence in India

- res – the plural of re, a name for one step of the musical scale; obsolete legal term for "the matter" or "incident"

- reais – the plural of real, the currency unit of Brazil

- réis - the plural of real, the former currency unit of Brazil

If proper names are included, then a possible nonet would be:

- Ayr – a town in Scotland

- Aire – a river in Yorkshire

- Eyre – legal term and various geographic locations

- heir – one who inherits

- air – the ubiquitous atmospheric gas that people breathe; a type of musical tune

- ere – poetic / archaic "before"

- e'er – poetic "ever" (some speakers)

- are – a metric unit of area, usually found in hectare[4]

Certain word pairs that were historically variant spellings of the same words, but eventually standardized as distinct homophonous words by mere spelling, include:

- flour[5] and flower:[6] flour is the older spelling used for the later meaning ("wheat powder," supposedly the "finest" part, the "bloom" of a meal;[7] compare French fleur de farine, literally "flower of flour"); flower is the later spelling used for the original meaning ("bloom"). The verb flourish ("blossom") is spelt more similarly to the noun flour ("wheat powder").

- discrete[8] and discreet:[9] discrete maintains the original meaning ("separate"); discreet is used for the later meaning ("prudent"), although the noun discretion ("prudence") looks more similar to discrete. The split in spelling occurred after during the late 16th century when discreet was favored for the popular meaning of "prudent," while discrete is favored in academic contexts.

- passed and past:[10] past was one of the many variants of the past participle passed of the Middle English verb passen (whence Modern English pass).[7] During the 14th century, past was used specifically as an adjective and preposition, and during the 15th century as a noun by ellipsis with the earlier adjective.[7] Compare the Romance cognates, French passé, Italian passato, Portuguese passado and Spanish pasado, all of which function as past participles, adjectives and nouns.

- born[11] and borne: these were variant spellings of the same past participle of bear, whose general meaning is "carry", but with one specific derived meaning, "birth". The distinction between born for "birthed" and borne for "carried" came to be sometime during the 17th century. Compare sworne, torne and worne,[7] variants of sworn, torn and worn, that did not survive into present-day English.

Its was merely the genitive form of it and derived by adding the apostrophe and s, thus originally spelt it's, making it also a homograph of it's (contraction of it is/has). The genitive it's was retained even toward the early 19th century.[7] The spelling of aisle[12] (from Middle French aisle, Old French aile, Latin ālam) was altered with the silent letter s due to its historical homophony with isle (Old French isle, Latin īnsulam) in both French and English. Spelling alteration (often based on etymology) can also obscure homophony, such as the case of colonel, which prevailed over the historical variant coronel by the late Modern English period, but which is now still pronounced identically to kernel as if the r were still there in the spelling.[7] The ye in dye is purposefully retained in its forms, especially its present participle dyeing, in order to distinguish it from the homophonous dying, which is the present participle of die.

Homophones can arise from borrowed words which end up being pronounced the same in English, such as profit (ultimately from Latin profectus) and prophet (ultimately from Greek προφήτης). Sometimes the English words are even homographs, such as quarry ('stone mine', from Latin quadraria) and quarry ('thing that is pursued', from Latin corata) or policy ('way of management', ultimately from Greek πολῑτείᾱ) and policy ('insurance contract', from Greek ἀπόδειξις via Latin apodīssa, Italian polizza and French police)—[13]see the discussion of English homographs from different Greek origins.

Many words were historically heterophonous, but after historical sound changes, including the Great Vowel Shift and various vowel mergers, they became homophonous. For example, ail and ale, both pronounced /ɛjl/ in Modern English, were respectively eile(n) /ˈɛjlə(n)/ and ale /ˈaːlə/ in Middle English before the Great Vowel Shift. The verbs lie (past tense and past participle lied) and lie (past tense lay, past participle lain) used to be lēogan [ˈleoːɣɑn] and liċġan [ˈliddʒɑn] in Old English; while will (past tense would) and will (past tense and past participle willed) used to be willan [ˈwiɫɫɑn] and willian [ˈwiɫɫiɑn].

Ax(e) (Middle English ax(i)e(n), Old English āxian/ācsian), an obsolescent variant of ask (Middle English ask(i)e(n), Old English āscian), is homophonous with ax(e) (cutting tool) in some Scottish accents, but with arcs in some English accents such as Multicultural London English.[14]

Epenthesis, which often occurs at the boundary between a nasal and a fricative, can cause some words that are phonemically distinct to become phonetically homophonous. For example, assistance may be pronounced [əˈsɪstənts], with an additional t like in assistants.

Brazilian Portuguese

[edit]The Portuguese language has one of the highest numbers of homophones.[citation needed] For example, jogo 'I throw', 'I play', 'match (sports)', and 'game' (in dialects like Paulistano it is not homophonic, while in Caipira it is).

German

[edit]There are many homophones in present-day standard German. As in other languages, however, there exists regional and/or individual variation in certain groups of words or in single words, so that the number of homophones varies accordingly. Regional variation is especially common in words that exhibit the long vowels ä and e. According to the well-known dictionary Duden, these vowels should be distinguished as /ɛ:/ and /e:/, but this is not always the case, so that words like Ähre (ear of corn) and Ehre (honor) may or may not be homophones. Individual variation is shown by a pair like Gäste (guests) – Geste (gesture), the latter of which varies between /ˈɡe:stə/ and /ˈɡɛstə/ and by a pair like Stiel (handle, stalk) – Stil (style), the latter of which varies between /ʃtiːl/ and /stiːl/.

Besides websites that offer extensive lists of German homophones,[15] there are others which provide numerous sentences with various types of homophones.[16] In the German language homophones occur in more than 200 instances. Of these, a few are triples like

- Waagen (weighing scales) – Wagen (cart) – wagen (to dare)

- Waise (orphan) – Weise (way, manner) – weise (wise)

Most are couples like lehren (to teach) – leeren (to empty).

Spanish

[edit]Spanish has many homophones, but fewer than English. Some are homonyms, such as basta, which can either mean 'enough' or 'coarse', and some exist because of homophonous letters. For example, the letters b and v are pronounced exactly alike, so the words basta (coarse) and vasta (vast) are pronounced identically.[17]

Other homonyms are spelled the same, but mean different things in different genders. For example, the masculine noun el capital means 'capital' as in 'money', but the feminine noun la capital means 'capital city'.[18]

Japanese

[edit]There are many homophones in Japanese, due to the use of Sino-Japanese vocabulary, where borrowed words and morphemes from Chinese are widely used in Japanese, but many phonemic contrasts, such as the original words' tones, are lost.

An extreme example is the pronunciation [kì̥kóō] which, accounting for the "flat" pitch accent, is used for the following words:

- 機構 (organization / mechanism)

- 紀行 (travelogue)

- 稀覯 (rare)

- 騎行 (horseback riding)

- 奇功 (outstanding achievement)

- 起稿 (draft)

- 奇行 (eccentricity)

- 機巧 (contrivance)

- 寄港 (stopping at port)

- 帰校 (returning to school)

- 気功 (breathing exercise, qigong)

- 寄稿 (contribute an article / a written piece)

- 機甲 (armor, e.g. of a tank)

- 帰航 (homeward voyage)

- 奇効 (remarkable effect)

- 季候 (season / climate)

- 気孔 (stoma)

- 起工 (setting to work)

- 気候 (climate)

- 帰港 (returning to port)

Upon adoption from Middle Chinese into Early Middle Japanese, certain sounds were modified or simplified to match Japanese phonology, causing homophony. For example, in the above list, 機構, 稀覯, 季候, 気功, 起稿, 帰校 and 紀行 may have been pronounced [kɨj˧ kəw˥˩], [hɨj˧ kəw˥˩], [kwi˥˩ ɦəw˥˩], [kʰɨj˥˩ kəwŋ˧], [kʰɨ˧˥ kaw˧˥], [kuj˧ ɦaɨw˥˩] and [kɨ˧˥ ɦaɨjŋ˧] in Middle Chinese, but [kikou], [kikou], [kikou], [kikoũ], [kikau], [kikau] and [kikaũ] in Japanese. Furthermore, there were vowel fusions and mergers during Late Middle Japanese which furthered even more homophony. For example, 機構, 奇功, 起稿 and 紀行 were once pronounced distinctly as [kikou], [kikoũ], [kikau] and [kikaũ], but now all as [kikoo].

Korean

[edit]The Korean language contains a combination of words that strictly belong to Korean and words that are loanwords from Chinese. Due to Chinese being pronounced with varying tones and Korean's removal of those tones, and because the modern Korean writing system, Hangeul, has a more finite number of phonemes than, for example, Latin-derived alphabets such as that of English, there are many homonyms with both the same spelling and pronunciation. For example

- 'Korean: 화장하다; Hanja: 化粧하다': 'to put on makeup' vs. '화장하다; 火葬하다': 'to cremate'

- '유산; 遺産': 'inheritance' vs. '유산; 流産': 'miscarriage'

- '방구': 'fart' vs. '방구; 防具': 'guard'

- '밤[밤ː]': 'chestnut' vs. '밤': 'night'

There are heterographs, but far fewer, contrary to the tendency in English. For example,

- '학문(學問)': 'learning' vs. '항문(肛門)': 'anus'.

Using hanja (한자; 漢字), which are Chinese characters, such words are written differently.

As in other languages, Korean homonyms can be used to make puns. The context in which the word is used indicates which meaning is intended by the speaker or writer.

Mandarin Chinese

[edit]Due to phonological constraints in Mandarin syllables (as Mandarin only allows for an initial consonant, a vowel, and a nasal or retroflex consonant in respective order), there are only a little over 400 possible unique syllables that can be produced,[19] compared to over 15,831 in the English language.[20]

Chinese has an entire genre of poems taking advantage of the large amount of homophones called one-syllable articles, or poems where every single word in the poem is pronounced as the same syllable if tones are disregarded. An example is the Lion-Eating Poet in the Stone Den.

Like all Chinese languages, Mandarin uses phonemic tones to distinguish homophonic syllables; Mandarin has five tones. A famous example,

- mā (妈) means "mother"

- má (麻) means "hemp"

- mă (马) means "horse"

- mà (骂) means "scold"

- ma (吗) is a yes / no question particle

Although all these words consist of the same string of consonants and vowels, the only way to distinguish each of these words audibly is by listening to which tone the word has, and as shown above, saying a consonant-vowel string using a different tone can produce an entirely different word altogether. If tones are included, the number of unique syllables in Mandarin increases to at least 1,522.[citation needed]

However, even with tones, Mandarin retains a very large amount of homophones. Yì, for example, has at least 125 homophones,[21] and it is the pronunciation used for Chinese characters such as 义, 意, 易, 亿, 议, 一, and 已.

There are even place names in China that have identical pronunciations, aside for the difference in tone. For example, there are two neighboring provinces with nearly identical names, Shanxi (山西) and Shaanxi (陕西). The only difference in pronunciation between the two names are the tone in the first syllable (Shanxi is pronounced ⓘ whereas Shaanxi is pronounced ⓘ). As most languages exclude the tone diacritics when transcribing Chinese place names into their own languages, the only way to visually distinguish the two names is to write Shaanxi in Gwoyeu Romatzyh romanization. Otherwise, nearly all other spellings of placenames in mainland China are spelled using Hanyu Pinyin romanization.

Many scholars believe that the Chinese language did not always have such a large number of homophones and that the phonological structure of Chinese syllables was once more complex, which allowed for a larger amount of possible syllables so that words sounded more distinct from each other.

Scholars also believe that Old Chinese had no phonemic tones, but tones emerged in Middle Chinese to replace sounds that were lost from Old Chinese. Since words in Old Chinese sounded more distinct from each other at this time, it explains why many words in Classical Chinese consisted of only one syllable. For example, the Standard Mandarin word 狮子(shīzi, meaning "lion") was simply 狮 (shī) in Classical Chinese, and the Standard Mandarin word 教育 (jiàoyù, "education") was simply 教 (jiào) in Classical Chinese.

Since many Chinese words became homophonic over the centuries, it became difficult to distinguish words when listening to documents written in Classical Chinese being read aloud. One-syllable articles like those mentioned above are evidence for this. For this reason, many one-syllable words from Classical Chinese became two-syllable words, like the words mentioned in the previous paragraph.

Even with the existence of two- or two-syllable words, however, there are even multisyllabic homophones. And there are also a lot of harmonic words. The cultural phenomenon brought about by such linguistic characteristics is that from ancient times to the present day, people have been keen to play games and jokes with homophonic and harmonic words. In modern life, the influence of homophones can be seen everywhere, from CCTV evening sketch programmes, folk art performances and popular folk life. In recent years, receiving the influence of Internet pop culture, young people have invented more new and popular homophones.[22] Homophones even play a major role in daily life throughout China, including Spring Festival traditions, which gifts to give (and not give), political criticism, texting, and many other aspects of people's lives.[23]

Another complication that arises within the Chinese language is that in non-rap songs, tones are disregarded in favor of maintaining melody in the song.[24] While in most cases, the lack of phonemic tones in music does not cause confusion among native speakers, there are instances where puns may arise.

Subtitles in Chinese characters are usually displayed on music videos and in songs sung on movies and TV shows to disambiguate the song's lyrics.

Russian

[edit]The presence of homophones in the Russian language is associated in some cases with the phenomenon of devoicing of consonants at the end of words and before another consonant sound, in other cases with the reduction of vowels in an unstressed position. Examples include: порог — порок — парок, луг — лук, плод — плот, туш — тушь, падёж — падёшь, бал — балл, косный — костный, предать — придать, компания — кампания, косатка — касатка, привидение — приведение, кот — код, прут — пруд, титрация — тетрация, комплимент — комплемент.

Also, in reflexive verbs, the infinitive and the present (or simple future) tense of the third person of the same verb are often pronounced the same way (in writing they differ in the presence or absence of the letter Ь (soft sign) before the postfix -ся): (надо) решиться — (он) решится, (хочу) строиться — (дом) строится, (металл может) гнуться — (деревья) гнутся, (должен) вернуться — (они) вернутся. This often leads to incorrect spelling of reflexive verbs ending with -ться/-тся: in some cases, Ь is mistakenly placed before -ся in the present tense of the third person, while in others, on the contrary, Ь before -ся is missing in the infinitive form.

Vietnamese

[edit]It is estimated that there are approximately 4,500 to 4,800 possible syllables in Vietnamese, depending on the dialect.[25] The exact number is difficult to calculate because there are significant differences in pronunciation among the dialects. For example, the graphemes and digraphs "d", "gi", and "r" are all pronounced /z/ in the Hanoi dialect, so the words dao (knife), giao (delivery), and rao (advertise) are all pronounced /zaw˧/. In Saigon dialect, however, the graphemes and digraphs "d", "gi", and "v" are all pronounced /j/, so the words dao (knife), giao (delivery), and vao (enter) are all pronounced /jaw˧/.

Pairs of words that are homophones in one dialect may not be homophones in the other. For example, the words sắc (sharp) and xắc (dice) are both pronounced /săk˧˥/ in Hanoi dialect, but pronounced /ʂăk˧˥/ and /săk˧˥/ in Saigon dialect respectively.

Psychological research

[edit]Pseudo-homophones

[edit]Pseudo-homophones are pseudowords that are phonetically identical to a word. For example, groan/grone and crane/crain are pseudo-homophone pairs, whereas plane/plain is a homophone pair since both letter strings are recognised words. Both types of pairs are used in lexical decision tasks to investigate word recognition.[26]

Use as ambiguous information

[edit]Homophones, specifically heterographs, where one spelling is of a threatening nature and one is not (e.g. slay/sleigh, war/wore) have been used in studies of anxiety as a test of cognitive models that those with high anxiety tend to interpret ambiguous information in a threatening manner.[27]

See also

[edit]- "Do-Re-Mi", a show tune from The Sound of Music that uses homophones (e.g. "doe", "ray", "me") to explain the notes in the solfège scale

- Homograph

- Homonym

- Synonym

- Dajare, a type of Japanese wordplay involving similar-sounding phrases

- Perfect rhyme

- Wiktionary

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ derived from Greek homo- (ὁμο‑) 'same' and phōnḗ (φωνή) 'voice, utterance'.[citation needed]

- ^ According to the strict sense of homonyms as words with the same spelling and pronunciation; however, homonyms according to the loose sense common in nontechnical contexts are words with the same spelling or pronunciation, in which case all homophones are also homonyms.[1]

- ^ The name oronym was first proposed and advocated by Gyles Brandreth in his book The Joy of Lex (1980), and such use was also accepted in the BBC programme Never Mind the Full Stops, which featured Brandreth as a guest.

References

[edit]- ^ "Homonym". Random House Unabridged Dictionary. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016 – via Dictionary.com.

- ^ Room 1996, p. 75.

- ^ Stewart 2015, p. 91, 237.

- ^ Burkardt, J. "Multinyms". Department of Scientific Computing. Fun / wordplay. Florida State University. Archived from the original on 25 August 2016.

- ^ "flour". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ "flower". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ a b c d e f Oxford English Dictionary

- ^ "discrete". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ "discreet". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ "past". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ "born". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ "aisle". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ "policy". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ Lindsey, Geoff (7 December 2022). Why do people say AKS instead of ASK?. YouTube.

- ^ See, e.g. "Homophone und homonyme im deutschen Homophone". yumpu.com (in German). Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ See Fausto Cercignani, "Beispielsätze mit deutschen Homophonen" [Example sentences with German homophones] (in German). Archived from the original on 29 May 2020.

- ^ "51 Spanish Words That Sound Exactly Like Other Spanish Words". ThoughtCo. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ "37 Spanish Nouns Whose Meanings Change With Gender". ThoughtCo. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ "Is there any similarity between Chinese and English?". Learn Mandarin Chinese Online. Study Online Mandarin Chinese Courses. 7 July 2017. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- ^ Barker (22 August 2016). "Syllables". Linguistics. New York University. Archived from the original on 22 August 2016. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- ^ Chang, Chao-Huang. "Corpus-based adaptation mechanisms for Chinese Homophone disambiguation" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- ^ "Mandarin Homophones Explained: Enhance Your Chinese Language Skills". chinesevoyage.org. 5 July 2024. Retrieved 4 July 2024.

- ^ "Chinese Homophones and Chinese Customs". yoyochinese.com (blog). Archived from the original on 9 April 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- ^ "How do people sing in a tonal language?". Diplomatic Language Services. 8 September 2016. Archived from the original on 28 November 2020. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- ^ "vietnamese tone marks pronunciation". pronunciator.com. Archived from the original on 18 May 2022. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ^ Martin, R.C. (1982). "The pseudohomophone effect: The role of visual similarity in non-word decisions". Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 34A (Pt 3): 395–409. doi:10.1080/14640748208400851. PMID 6890218. S2CID 41699283.

- ^ Mogg, K.; Bradley, B.P.; Miller, T.; Potts, H.; Glenwright, J.; Kentish, J. (1994). "Interpretation of homophones related to threat: Anxiety or response bias effects?". Cognitive Therapy and Research. 18 (5): 461–477. doi:10.1007/BF02357754. S2CID 36150769.

Sources

[edit]- Franklyn, Julian (1966). Which Witch? (1st ed.). New York, NY: Dorset Press. ISBN 0-88029-164-8.

- Room, Adrian (1996). An Alphabetical Guide to the Language of Name Studies. Lanham and London, UK: The Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-081083169-8. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- Stewart, Garrett (2015). The Deed of Reading: Literature, writing, language, philosophy. Ithaca, NY and London, UK: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-150170170-2. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

External links

[edit]- Homophone.com Archived 7 May 2021 at the Wayback Machine – a list of American homophones with a searchable database

- Reed's homophones – a book of sound-alike words published in 2012

- Homophones.ml Archived 6 May 2021 at the Wayback Machine – a collection of homophones and their definitions

- Homophone Machine Archived 14 May 2021 at the Wayback Machine – swaps homophones in any sentence

- Useful tips ... English homophones – homophones list, activities and worksheets

Homophone

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition

A homophone is one of two or more words, or sometimes phrases, that are pronounced the same (or nearly identically) but differ in meaning, and typically in spelling or derivation.[11] This phonetic identity arises in the spoken form of a language, where the sounds align despite distinct semantic roles, as seen in the English pair "to," "too," and "two," all pronounced /tuː/ in standard dialects but conveying direction, excess, or the numeral, respectively.[11] Note that the distinction between homophones and homonyms can vary by linguistic framework; some treat homophony as a subset of homonymy. Homophones are typically etymologically unrelated, distinguishing them from cases of polysemy where a single word form carries multiple related meanings. The criteria for homophony emphasize phonetic sameness in a given language's standard pronunciation, though minor variations may occur across dialects without negating the classification.[12] For instance, while General American English treats "cot" and "caught" as distinct, certain dialects merge them into homophones, highlighting how regional accents can influence perceived identity.[12] Linguists prioritize standard forms for defining homophones to maintain consistency in analysis, allowing for dialectal allowances only where the core sound overlap persists.[2] This scope extends to homophonic phrases, such as "ice cream" and "I scream," where multi-word units share pronunciation but diverge in sense, though detailed exploration of such cases appears in language-specific contexts.[11] Homonyms are words that are both pronounced and spelled the same but have different meanings (e.g., "bank" for river or money); homophones, by contrast, share pronunciation regardless of spelling.[13]Etymology

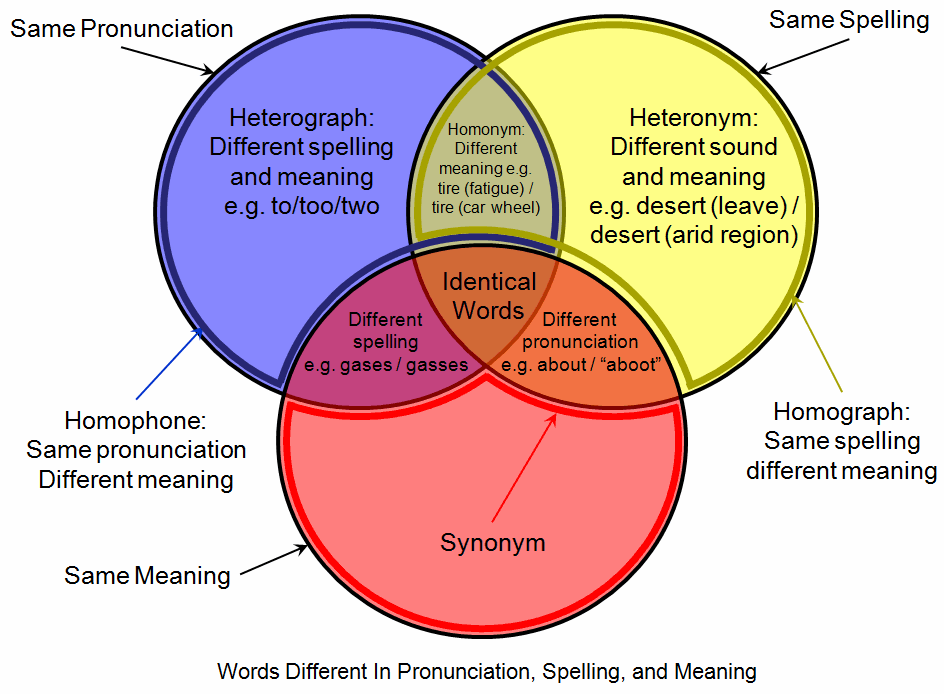

The term "homophone" derives from the Greek homos (ὁμός), meaning "same," and phōnē (φωνή), meaning "sound" or "voice," literally signifying "of the same sound." This compound entered European languages through classical scholarship, initially describing phenomena in rhetoric and music where sounds or voices aligned identically.[14][15] The earliest attested use in English linguistics dates to 1623, in Henry Cockeram's The English Dictionarie: Or, An Interpreter of Hard Vvords, where "homophone" referred to a word pronounced the same as another but differing in meaning and etymology. Cockeram's work, one of the earliest monolingual English dictionaries, marked the term's adoption into lexical studies, reflecting Renaissance interest in clarifying ambiguities in the vernacular. Although the concept of same-sounding words was discussed in classical texts like Aristotle's Poetics for rhetorical effects, the specific term "homophone" emerged in modern form during this period to address pronunciation in emerging grammars.[16] Over time, the term evolved from rhetorical and lexical applications to a core element in phonology. In the 19th century, with the rise of comparative linguistics—exemplified by scholars like Jacob Grimm—it shifted toward systematic analysis of sound patterns across languages, distinguishing homophones as instances of phonological overlap. By the 20th century, in structuralist frameworks such as those of the Prague School, homophones became key to understanding phonemic distinctions and lexical ambiguity, influencing fields from dialectology to computational linguistics.[16][14] A related term, "homonym," originates from Greek homos combined with onoma (ὄνομα), meaning "name," denoting words sharing form (spelling or pronunciation) but not origin or meaning. First recorded in English in 1807 via French homonyme, it broadened the discussion of lexical similarity beyond sound alone.[17]Related Concepts

Homonyms and Homographs

In linguistics, homonyms are defined as words that are identical in both spelling and pronunciation but differ in meaning and typically originate from unrelated etymological roots. For instance, "bank" can refer to the side of a river or a financial institution, representing two distinct concepts with the same phonetic and orthographic form. This strict usage of homonymy emphasizes complete formal identity alongside semantic divergence.[18] Homographs, by contrast, are words that share the same spelling but differ in pronunciation and meaning, often due to different historical developments. An example is "lead," which as a noun denoting the metal is pronounced /lɛd/, while as a verb meaning to guide is pronounced /liːd/.[19] Unlike homonyms, homographs do not require identical pronunciation, allowing for cases where visual similarity leads to potential confusion in reading.[20] Homophones relate to both concepts as words that are pronounced identically but may differ in spelling and meaning, such as "pair" (a set) and "pear" (fruit). In precise terms, homophones with identical spelling are subsumed under homonyms, forming an overlap where the words are both homophonous and homographic. However, true homophones often involve spelling differences, distinguishing them from strict homonyms. This intersection can be conceptualized as a set of overlapping categories: homonyms occupy the core where sound and spelling fully coincide with distinct meanings; homophones extend to include spelling variants with shared pronunciation; and homographs branch out to encompass pronunciation variants with shared spelling.[21] A common confusion arises in non-specialist contexts, where "homonyms" is frequently applied loosely to encompass both homophones and homographs, blurring the distinctions for simplicity in everyday language discussions. This broader application stems from the Greek roots of the terms—homo- meaning "same" and -nym meaning "name"—leading to interchangeable use despite the more nuanced linguistic classifications.[19] Such mislabeling can obscure the role of homophones specifically as sound-based ambiguities, separate from orthographic or combined factors.[20]Phonetic and Orthographic Distinctions

Homophones arise primarily from phonological processes in spoken language, where distinct phonemes converge or merge over time, leading to words that sound identical despite different meanings and spellings. This convergence often results from sound changes such as vowel shifts or consonant mergers, which reduce the inventory of contrastive sounds in a language's phonemic system. For instance, phonemic mergers occur when historically distinct sounds become indistinguishable, creating new homophones; a classic example is the Great Vowel Shift in English, which altered vowel qualities and contributed to pairs like "meet" and "meat" becoming homophonous.[22][23] A specific mechanism of phoneme convergence is consonant flapping, prevalent in many dialects of English, where the phonemes /t/ and /d/ are realized as a single alveolar flap [ɾ] in intervocalic positions. This process neutralizes the contrast between these sounds, turning words like "writer" (/ˈraɪtər/) and "rider" (/ˈraɪdər/) into homophones in casual speech. Flapping is a conditioned phonetic variation governed by the surrounding environment, such as between vowels with secondary stress on the following syllable, and is a hallmark of North American English varieties.[24][25] Orthographic distinctions among homophones stem largely from the irregularities in English spelling, which do not consistently reflect phonetic reality due to historical influences like the Norman Conquest of 1066. This event introduced a flood of French-derived vocabulary and Norman scribes who imposed French orthographic conventions on English words, often preserving etymological spellings that diverged from evolving pronunciations. As a result, words like "right," "rite," "write," and "wright" share the same phonetic form /raɪt/ but retain distinct spellings reflecting their disparate origins—Germanic for "right" and "wright," Latin via French for "rite" and "write"—exacerbating homophony in writing.[26][27] Dialectal variations further influence homophone status by altering pronunciation patterns across regions, making certain pairs homophonous in one accent but not another. For example, the cot–caught merger, common in many North American dialects but absent in most British varieties, causes words like "cot" (/kɑt/) and "caught" (/kɔt/) to become homophones in merged dialects, where both are pronounced with the same low back vowel [ɑ]. In contrast, British English typically maintains a distinction with [ɒ] for "cot" and [ɔː] for "caught." Such mergers reflect ongoing phonological simplification in dialects and can shift the homophone inventory regionally.[28][29] To distinguish true homophones from near-homophones, it is essential to differentiate phonemes—contrastive sound units that distinguish meaning—from allophones, which are non-contrastive variants of a phoneme determined by phonetic context. Allophones do not create homophony because they do not alter word identity; for instance, the aspirated [pʰ] in "pin" and unaspirated in "spin" are allophones of /p/ in English, so "pin" and "spin" remain distinct despite subtle acoustic differences. In dialects with flapping, words like "ladder" (/ˈlædər/) and "latter" (/ˈlætər/) become homophones, as both /t/ and /d/ are realized as [ɾ], creating phonetic identity despite phonemic differences. This illustrates how allophonic rules can lead to homophony between distinct phonemes.[30][31][32]Homophones in English

Common Examples

Homophones are words in English that share the same pronunciation but differ in spelling and meaning, often leading to confusion in writing. Common examples abound in everyday language, particularly among frequently used words. These pairs or sets are typically categorized by their shared phonetic sound, as identified in standard American and British English pronunciations. For instance, homophones pronounced with the vowel sound /eɪ/ include "ate" (past tense of eat) and "eight" (the number 8), while those with /ɪr/ encompass "ear" (organ of hearing) and "here" (in this place). Such categorizations highlight how homophony arises from phonetic similarities, a distinction rooted in orthographic variations. To illustrate prevalent examples, the following table lists selected homophone pairs grouped by common phonetic sounds, including their spellings and primary meanings. This selection draws from standard dictionaries and focuses on high-utility words encountered in general communication.| Phonetic Sound | Homophone Set | Spellings and Meanings |

|---|---|---|

| /eɪ/ | ate/eight | ate: consumed food; eight: numeral 8. |

| /iː/ | be/bee | be: exist or occur; bee: flying insect. |

| /aɪ/ | eye/I | eye: organ of sight; I: first-person pronoun. |

| /noʊ/ | know/no | know: possess knowledge; no: negative response. |

| /tuː/ | to/too/two | to: preposition indicating direction; too: also or excessively; two: numeral 2. |

| /ðɛr/ | there/their/they're | there: in that place; their: possessive form of they; they're: contraction of they are. |

| /prɪnsɪpəl/ | principal/principle | principal: main or head of school; principle: fundamental truth. |