Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Carbenicillin

View on Wikipedia | |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Geocillin; Pyopen |

| Other names | CB[1] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral, parenteral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 30 to 40% |

| Protein binding | 30 to 60% |

| Metabolism | Minimal |

| Elimination half-life | 1 hour |

| Excretion | Renal (30 to 40%) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.022.882 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C17H18N2O6S |

| Molar mass | 378.40 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Carbenicillin is a bactericidal antibiotic belonging to the carboxypenicillin subgroup of the penicillins.[2] It was discovered by scientists at Beecham and marketed as Pyopen. It has Gram-negative coverage which includes Pseudomonas aeruginosa but limited Gram-positive coverage. The carboxypenicillins are susceptible to degradation by beta-lactamase enzymes, although they are more resistant than ampicillin to degradation. Carbenicillin is also more stable at lower pH than ampicillin.

Pharmacology

[edit]The antibiotic is highly soluble in water and is acid-labile. A typical lab working concentration is 50 to 100 μg per mL.[citation needed]

It is a semi-synthetic analogue of the naturally occurring benzylpenicillin. Carbenicillin at high doses can cause bleeding. Use of carbenicillin can cause hypokalemia by promoting potassium loss at the distal convoluted tubule of the kidney.[citation needed]

In molecular biology, carbenicillin may be preferred as a selecting agent (see plasmid stabilisation technology) because its breakdown results in byproducts with a lower toxicity than analogous antibiotics like ampicillin. Carbenicillin is more stable than ampicillin and results in fewer satellite colonies on selection plates. However, in most situations this is not a significant problem so ampicillin is sometimes used due to its lower cost.[citation needed]

Spectrum of bacterial susceptibility and resistance

[edit]Carbenicillin has been shown to be effective against bacteria responsible for causing urinary tract infections including Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, and some Proteus species. The following represents carbenicillin susceptibility data for a few medically significant organisms.[3] This is not representative of all species of bacteria susceptible to carbenicillin exposure.

- Escherichia coli 1.56 μg/ml - 64 μg/ml

- Proteus mirabilis 1.56 μg/ml - 3.13 μg/ml

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa 3.13 μg/ml - >1024 μg/ml

References

[edit]- ^ "Antibiotic abbreviations list". Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- ^ Basker MJ, Comber KR, Sutherland R, Valler GH (1977). "Carfecillin: antibacterial activity in vitro and in vivo". Chemotherapy. 23 (6): 424–35. doi:10.1159/000222012. PMID 21771.

- ^ "Carbenicillin Disodium, USP Susceptibility and Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) Data" (PDF). January 6, 2020.

Further reading

[edit]Carbenicillin

View on GrokipediaHistory and Development

Discovery

Carbenicillin was discovered by scientists at Beecham Research Laboratories in the early 1960s as part of broader efforts to develop semi-synthetic penicillins with enhanced efficacy against Gram-negative bacteria, building on the 1957 isolation of 6-aminopenicillanic acid (6-APA) that enabled side-chain modifications to the penicillin core.[8] Researchers, including Edward George Brain and John Herbert Charles Nayler, focused on derivatives that could address limitations of earlier penicillins like ampicillin, which showed only modest activity against challenging pathogens such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa.[9] The initial synthesis of carbenicillin, chemically known as α-carboxybenzylpenicillin, occurred through acylation of 6-APA with a reactive derivative of phenylmalonic acid, incorporating a carboxyphenyl side chain to improve stability and penetration against Gram-negative organisms. This semi-synthetic approach modified the benzyl side chain of benzylpenicillin (penicillin G) to confer the desired spectrum. The first reported synthesis was detailed in a 1965 British patent filed in 1963, marking a pivotal advancement in antipseudomonal therapy.[9][10] Early preclinical studies rapidly demonstrated carbenicillin's superior antibacterial activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa compared to prior penicillins, including ampicillin, with minimum inhibitory concentrations often 4- to 16-fold lower in vitro. For instance, a 1967 investigation reported that carbenicillin inhibited 90% of P. aeruginosa strains at concentrations of 50-100 μg/mL, significantly outperforming ampicillin's higher thresholds of 200-500 μg/mL, while retaining activity against other Gram-negatives like Proteus and Escherichia coli. These findings, from laboratory assays on clinical isolates, underscored carbenicillin's potential as the first penicillin with clinically viable antipseudomonal effects, paving the way for subsequent clinical evaluation by Beecham.[11][4]Market Introduction and Current Status

Carbenicillin was commercialized in the late 1960s by Beecham Research Laboratories, initially as the injectable disodium salt under the brand name Pyopen for treating severe bacterial infections.[12] The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the injectable form in 1970 specifically for urinary tract infections caused by susceptible gram-negative bacteria.[13] In 1972, the FDA approved the oral indanyl sodium ester formulation, marketed as Geocillin, expanding accessibility for outpatient treatment of urinary tract infections.[14] During the 1970s and 1980s, carbenicillin reached peak clinical usage, particularly for infections caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa, where it was often combined with aminoglycosides for enhanced efficacy against this challenging pathogen.[15] However, by the late 1980s, its role diminished as broader-spectrum carboxypenicillins like piperacillin, which demonstrated superior in vitro activity against Pseudomonas species, became preferred alternatives.[16] As of 2025, carbenicillin has been largely discontinued for human clinical use in major markets, including the United States, due to widespread bacterial resistance and the availability of more effective antibiotics; the oral Geocillin was withdrawn by its manufacturer in 2008.[17] It remains available primarily for laboratory applications, such as plasmid selection in molecular biology research, with small-scale production ongoing to support these non-clinical needs. Beecham's original portfolio, including carbenicillin, was integrated into SmithKline Beecham following its 1989 merger with SmithKline Beckman, and further consolidated under GlaxoSmithKline after the 2000 acquisition of SmithKline Beecham by Glaxo Wellcome, which streamlined global distribution but eventually contributed to the phase-out of older antibiotics like carbenicillin in favor of newer innovations.[18][19]Chemical Structure and Properties

Molecular Formula and Structure

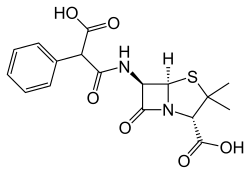

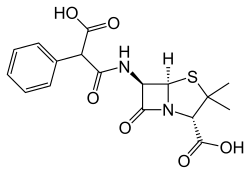

Carbenicillin, in its free acid form, has the molecular formula C₁₇H₁₈N₂O₆S, while the disodium salt, which is the predominant pharmaceutical form, possesses the formula C₁₇H₁₆N₂Na₂O₆S.[20] The core structure of carbenicillin consists of a β-lactam ring fused to a thiazolidine ring, forming the characteristic penam nucleus central to all penicillins. At the 6-position of this nucleus, a 6β-(2-carboxy-2-phenylacetamido) side chain is attached via an amide bond, which defines its classification as a carboxypenicillin. The full systematic IUPAC name is (2S,5R,6R)-6-[(2-carboxy-2-phenylacetyl)amino]-3,3-dimethyl-7-oxo-4-thia-1-azabicyclo[3.2.0]heptane-2-carboxylic acid. This side chain features a phenyl group and an α-carboxylic acid substituent on the acetyl moiety, distinguishing it from narrower-spectrum penicillins. The standard 2D structural diagram illustrates the bicyclic system, with the five-membered thiazolidine ring bearing a carboxylic acid at position 2 and two methyl groups at position 3, alongside the strained four-membered β-lactam ring bearing the amide side chain at position 6.[12][20] In terms of stereochemistry, carbenicillin maintains the specific configurations at key chiral centers in the penam nucleus: 2S at the thiazolidine carboxylic acid-bearing carbon, 5R at the fusion point, and 6R at the amide attachment site, ensuring the β-orientation of the side chain essential for biological activity. Compared to the parent penicillin G, which features a simple phenylacetamido side chain (–NH–C(O)–CH₂–Ph), carbenicillin's addition of a carboxy group at the α-position of the phenylacetic acid side chain (–NH–C(O)–CH(Ph)(COOH)) imparts enhanced acid stability and broadened activity against Gram-negative bacteria.[12][21]Physical and Chemical Characteristics

Carbenicillin appears as a white to off-white crystalline powder in its free acid form, while the disodium salt is typically a white to pale yellow powder.[22][23] The compound exhibits high solubility in water, with the disodium salt dissolving up to 50 mg/mL, though it is less soluble in ethanol and poorly soluble in most organic solvents.[24][25] It is acid-labile, degrading rapidly below pH 3 due to hydrolysis of the β-lactam ring, with a half-life of less than 30 minutes at pH 2.0.[1][26] Carbenicillin demonstrates stability in neutral to alkaline solutions (pH 5.5–8.0), where it remains effective for extended periods under refrigerated storage, but it is unstable to heat and exhibits strong hygroscopicity, requiring desiccated conditions at -20°C for long-term preservation.[24][22] The free acid has a molecular weight of 378.40 g/mol, while the disodium salt is 422.36 g/mol. Its pKa values include approximately 2.22 for one carboxylic acid group and 3.25 for the other, influencing its ionization and solubility in physiological conditions.[22] Carbenicillin is more resistant to β-lactamase hydrolysis than ampicillin but remains susceptible to degradation by these enzymes.[12] Common formulations include the disodium salt for intravenous or intramuscular injection, providing high aqueous solubility for parenteral administration, and the indanyl sodium ester for oral use to enhance gastrointestinal absorption.[27][28]Medical and Laboratory Applications

Therapeutic Indications

Carbenicillin, a semisynthetic penicillin antibiotic, was primarily indicated for the treatment of acute and chronic infections of the upper and lower urinary tract, prostatitis, and asymptomatic bacteriuria caused by susceptible Gram-negative bacteria such as Escherichia coli, Proteus mirabilis, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa.[12][29][30] However, carbenicillin has been discontinued for medical use in the United States since 2008 due to the availability of more effective alternatives.[17][31] Secondary indications included systemic infections such as septicemia, lower respiratory tract infections, skin and soft tissue infections, and bone and joint infections when caused by sensitive organisms, particularly Pseudomonas species.[32][33][34] In the 1970s, carbenicillin was particularly preferred for managing Pseudomonas infections in immunocompromised patients, often in combination with gentamicin to enhance efficacy against severe cases like those in granulocytopenic individuals.[35][36] Contraindications include hypersensitivity to penicillins, and caution is advised in patients with renal impairment due to reduced excretion and potential accumulation.[29][37][38] Clinical trials demonstrated efficacy in urinary tract infections caused by susceptible strains, with bacteriologic cure rates ranging from 70% to 90% in uncomplicated cases, though rates varied based on infection severity and organism sensitivity.[39][40] For Pseudomonas infections, response rates reached up to 91% in treated cases.[36]Dosage and Administration

Carbenicillin was available in parenteral forms (disodium salt) for intravenous (IV) or intramuscular (IM) administration and in oral form as carbenicillin indanyl sodium (Geocillin) for less severe infections, but both forms were discontinued in 2008 and are no longer available for medical use.[37][41][17] For adults with uncomplicated urinary tract infections (UTIs), the recommended oral dose was 382–764 mg (1–2 tablets) every 6 hours for 3–7 days.[37] For more serious UTIs or prostatitis, the oral dose was 764 mg every 6 hours for 14 days, with chronic prostatitis potentially requiring 1–3 months of therapy.[37] Parenteral administration was preferred for severe infections; typical adult doses included 1–2 g IV or IM every 6 hours for UTIs, escalating to 15–30 g/day IV in divided doses every 4–6 hours for life-threatening conditions such as septicemia.[41] Treatment duration generally ranged from 7–14 days for UTIs, extending longer for complicated or systemic infections based on clinical response.[37] In pediatric patients, the IV dose was 50–200 mg/kg/day divided every 4–6 hours, with adjustments for age, weight, and infection severity; maximum daily doses should not exceed adult equivalents.[1] Oral use in children was limited due to insufficient data on safety and efficacy.[2] Dosage adjustments were necessary in renal impairment to prevent accumulation, as carbenicillin is primarily excreted by the kidneys. The following table outlines recommended IV dosing for adults (70 kg) based on creatinine clearance (CrCl):| CrCl (mL/min) | Dose (g) / Interval (hours) |

|---|---|

| >50 | 1–2 / 4–6 |

| 10–50 | 1–2 / 6–12 |

| <10 | 1 / 12 (or avoid if possible) |

Use in Molecular Biology

In molecular biology, carbenicillin serves primarily as a selective agent for identifying and maintaining bacterial transformants that carry plasmids conferring ampicillin resistance, particularly in Escherichia coli strains.[43] This application leverages its compatibility with β-lactamase-producing genes (such as bla or ampR) commonly found in cloning vectors, allowing researchers to isolate successfully transformed cells on selective media.[44] Typical protocols involve incorporating carbenicillin into Luria-Bertani (LB) agar plates or broth at concentrations of 50–100 μg/mL to support plasmid propagation during routine cloning experiments.[45][46] Compared to ampicillin, carbenicillin offers enhanced stability in culture media, reducing degradation by β-lactamases secreted from nearby resistant "satellite" colonies and minimizing the formation of such colonies that can complicate selection.[43] This stability results in fewer toxic byproducts and more reliable selection outcomes, making it preferable for long-term plasmid maintenance and high-throughput screening.[44] Its chemical properties contribute to sustained activity in agar plates stored at 4°C for several weeks, unlike ampicillin which breaks down more readily.[47] Beyond bacterial cloning, carbenicillin is widely used in plant tissue culture protocols involving Agrobacterium-mediated transformation, where it eliminates residual Agrobacterium tumefaciens cells post-co-cultivation without excessively harming explants.[48] Concentrations of 250–500 mg/L are commonly added to selection media to suppress bacterial overgrowth while allowing transformed plant cells to regenerate.[49] For laboratory preparation, carbenicillin is available as a disodium salt powder from suppliers like Sigma-Aldrich, which is filter-sterilized and added to autoclaved media to ensure sterility and potency.[50]Pharmacology

Mechanism of Action

Carbenicillin, a semisynthetic beta-lactam antibiotic, acts bactericidally by binding to penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs) in the cytoplasmic membranes of susceptible bacteria, such as PBP-3.[12][51] These PBPs function as transpeptidases that catalyze the cross-linking of peptidoglycan strands during the final stage of bacterial cell wall synthesis. By acylating the active site serine residue of these enzymes through its beta-lactam ring, carbenicillin irreversibly inhibits their activity, preventing the formation of the rigid peptidoglycan layer essential for maintaining bacterial integrity.[12][1] This disruption weakens the cell wall, activating autolytic enzymes and leading to osmotic lysis, particularly in actively dividing bacteria where peptidoglycan synthesis is most active.[12] The bactericidal effect is time-dependent, requiring sustained inhibition during bacterial replication to achieve maximal efficacy.[52] Carbenicillin's spectrum favors Gram-negative bacteria due to its alpha-carboxy side chain, which imparts a di-anionic charge at physiological pH, facilitating passive diffusion through outer membrane porins in Gram-negative bacteria.[53] This structural feature enhances penetration compared to less polar penicillins, enabling activity against organisms like Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Proteus species.[12] While carbenicillin is susceptible to hydrolysis by certain beta-lactamases, it demonstrates greater stability than narrow-spectrum penicillins like ampicillin, attributed to steric hindrance from the bulky 2-carboxy-2-phenylacetamido side chain that impedes enzyme access to the beta-lactam ring.[12][54] As mammalian cells lack peptidoglycan and corresponding PBPs, carbenicillin exerts no direct cytotoxic effects on host tissues.[1]Pharmacokinetics

Carbenicillin is administered orally as the indanyl ester prodrug, which exhibits 30-40% bioavailability after rapid absorption from the small intestine, followed by hydrolysis to the active form in the body.[12] Intravenous or intramuscular administration achieves complete and immediate bioavailability.[55] The drug distributes widely with a volume of distribution of approximately 0.18 L/kg in adults.[56] It achieves high concentrations in urine (e.g., 800 to 5500 μg/mL in newborns after high doses), making it suitable for urinary tract infections.[15] Penetration into cerebrospinal fluid is generally poor, with CSF/serum ratios around 10-15% even in the presence of meningeal inflammation.[57] Plasma protein binding ranges from 30% to 60%.[12] Metabolism of carbenicillin is minimal in the liver, with the parent compound primarily excreted unchanged.[12] Excretion occurs mainly via the kidneys through both glomerular filtration and tubular secretion, with 80-99% of an intravenous dose recovered unchanged in the urine within 24 hours.[55][58] The elimination half-life is approximately 1 hour in individuals with normal renal function but prolongs significantly to 10-20 hours in anuria or severe renal failure.[59] For therapeutic efficacy, particularly against susceptible pathogens like Pseudomonas, peak serum levels of 200-400 μg/mL are typically achieved and targeted following high-dose intravenous administration.[15]Spectrum of Activity and Resistance

Susceptible Organisms

Carbenicillin exhibits a broad spectrum of antibacterial activity, primarily targeting gram-negative aerobic bacteria, with notable efficacy against certain pathogens responsible for urinary tract infections and systemic infections. Key susceptible gram-negative aerobes include Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which is a primary target due to carbenicillin's enhanced penetration through the outer membrane enabled by its carboxyl group, Escherichia coli, Proteus mirabilis, Morganella morganii, and Providencia rettgeri. Variable susceptibility is observed among Klebsiella pneumoniae and other Enterobacteriaceae, where activity may be reduced in beta-lactamase-producing strains.[12] In vitro studies demonstrate effective inhibition of these organisms at clinically achievable concentrations. For instance, minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) ranges for carbenicillin include 0.78–12.5 μg/mL against E. coli, 1.56–3.4 μg/mL against P. mirabilis, and 12.5–>200 μg/mL against P. aeruginosa, reflecting strain variability but overall susceptibility in sensitive isolates. These data underscore carbenicillin's role in treating infections caused by Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonas species, particularly in urinary and systemic contexts, though it is not typically first-line therapy. Activity against gram-positive bacteria is limited compared to other penicillins, with moderate effects on some streptococci but inferior performance against staphylococci and enterococci. Streptococcus species show susceptibility at lower MICs (e.g., ≤1.56 μg/mL for group A streptococci), but carbenicillin is rarely used for these due to more potent alternatives. Against anaerobes, activity is restricted; for example, only 67% of Bacteroides fragilis strains have an MIC ≤100 μg/mL, limiting its utility in anaerobic infections.[60][61]| Organism | Example MIC Range (μg/mL) |

|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | 0.78–12.5 |

| Proteus mirabilis | 1.56–3.4 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 12.5–>200 |

| Bacteroides fragilis | ≤100 (67% strains) |