Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Tongue

View on Wikipedia| Tongue | |

|---|---|

The human tongue | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Pharyngeal arches, lateral lingual swelling, tuberculum impar[1] |

| System | Alimentary tract, gustatory system |

| Artery | Lingual, tonsillar branch, ascending pharyngeal |

| Vein | Lingual |

| Nerve | Sensory Anterior two-thirds: Lingual (sensation) and chorda tympani (taste) Posterior one-third: Glossopharyngeal (IX) Motor Hypoglossal (XII), except palatoglossus muscle supplied by the pharyngeal plexus via vagus (X) |

| Lymph | Deep cervical, submandibular, submental |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | lingua |

| MeSH | D014059 |

| TA98 | A05.1.04.001 |

| TA2 | 2820 |

| FMA | 54640 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The tongue is a muscular organ in the mouth of a typical tetrapod. It manipulates food for chewing and swallowing as part of the digestive process, and is the primary organ of taste. The tongue's upper surface (dorsum) is covered by taste buds housed in numerous lingual papillae. It is sensitive and kept moist by saliva and is richly supplied with nerves and blood vessels. The tongue also serves as a natural means of cleaning the teeth.[2] A major function of the tongue is to enable speech in humans and vocalization in other animals.

The human tongue is divided into two parts, an oral part at the front and a pharyngeal part at the back. The left and right sides are also separated along most of its length by a vertical section of fibrous tissue (the lingual septum) that results in a groove, the median sulcus, on the tongue's surface.

There are two groups of glossal muscles. The four intrinsic muscles alter the shape of the tongue and are not attached to bone. The four paired extrinsic muscles change the position of the tongue and are anchored to bone.

Etymology

[edit]The word tongue derives from the Old English tunge, which comes from Proto-Germanic *tungōn.[3] It has cognates in other Germanic languages—for example tonge in West Frisian, tong in Dutch and Afrikaans, Zunge in German, tunge in Danish and Norwegian, and tunga in Icelandic, Faroese and Swedish. The ue ending of the word seems to be a fourteenth-century attempt to show "proper pronunciation", but it is "neither etymological nor phonetic".[3] Some used the spelling tunge and tonge as late as the sixteenth century.

In humans

[edit]Structure

[edit]

The tongue is a muscular hydrostat that forms part of the floor of the oral cavity. The left and right sides of the tongue are separated by a vertical section of fibrous tissue known as the lingual septum. This division is along the length of the tongue save for the very back of the pharyngeal part and is visible as a groove called the median sulcus. The human tongue is divided into anterior and posterior parts by the terminal sulcus, which is a "V"-shaped groove. The apex of the terminal sulcus is marked by a blind foramen, the foramen cecum, which is a remnant of the median thyroid diverticulum in early embryonic development. The anterior oral part is the visible part situated at the front and makes up roughly two-thirds the length of the tongue. The posterior pharyngeal part is the part closest to the throat, roughly one-third of its length. These parts differ in terms of their embryological development and nerve supply.

The anterior tongue is, at its apex, thin and narrow. It is directed forward against the lingual surfaces of the lower incisor teeth. The posterior part is, at its root, directed backward, and connected with the hyoid bone by the hyoglossi and genioglossi muscles and the hyoglossal membrane, with the epiglottis by three glossoepiglottic folds of mucous membrane, with the soft palate by the glossopalatine arches, and with the pharynx by the superior pharyngeal constrictor muscle and the mucous membrane. It also forms the anterior wall of the oropharynx.

The average length of the human tongue from the oropharynx to the tip is 10 cm.[4] The average weight of the human tongue from adult males is 99g and for adult females 79g.[5]

In phonetics and phonology, a distinction is made between the tip of the tongue and the blade (the portion just behind the tip). Sounds made with the tongue tip are said to be apical, while those made with the tongue blade are said to be laminal.

Tongue posture is the resting position of the tongue in the mouth. Evidence demonstrates that the tongue plays a role in mouth and face development.[6][7]

Upper surface

[edit]

The upper surface of the tongue, the dorsal surface, is called the dorsum, and is divided by a groove into symmetrical halves by the median sulcus. The foramen cecum marks the end of this division (at about 2.5 cm from the root of the tongue) and the beginning of the terminal sulcus. The foramen cecum is also the point of attachment of the thyroglossal duct and is formed during the descent of the thyroid diverticulum in embryonic development.

The terminal sulcus is a shallow groove that runs forward as a shallow groove in a V shape from the foramen cecum, forwards and outwards to the margins (borders) of the tongue. The terminal sulcus divides the tongue into a posterior pharyngeal part and an anterior oral part. The pharyngeal part is supplied by the glossopharyngeal nerve and the oral part is supplied by the lingual nerve (a branch of the mandibular branch (V3) of the trigeminal nerve) for somatosensory perception and by the chorda tympani (a branch of the facial nerve) for taste perception.

Both parts of the tongue develop from different pharyngeal arches.

Undersurface

[edit]On the undersurface, the ventral surface, of the tongue is a fold of mucous membrane called the frenulum that tethers the tongue at the midline to the floor of the mouth. On either side of the frenulum are small prominences called sublingual caruncles that the major salivary submandibular glands drain into.

Muscles

[edit]The eight muscles of the human tongue are classified as either intrinsic or extrinsic. The four intrinsic muscles act to change the shape of the tongue, and are not attached to any bone. The four extrinsic muscles act to change the position of the tongue, and are anchored to bone.

Extrinsic

[edit]

The four extrinsic muscles originate from bone and extend to the tongue. They are the genioglossus, the hyoglossus (often including the chondroglossus) the styloglossus, and the palatoglossus. Their main functions are altering the tongue's position allowing for protrusion, retraction, and side-to-side movement.[8]

The genioglossus arises from the mandible and protrudes the tongue. It is also known as the tongue's "safety muscle" since it is the only muscle that propels the tongue forward.

The hyoglossus, arises from the hyoid bone and retracts and depresses the tongue. The chondroglossus is often included with this muscle.

The styloglossus arises from the styloid process of the temporal bone and draws the sides of the tongue up to create a trough for swallowing.

The palatoglossus arises from the palatine aponeurosis, and depresses the soft palate, moves the palatoglossal fold towards the midline, and elevates the back of the tongue during swallowing.

Intrinsic

[edit]

Four paired intrinsic muscles of the tongue originate and insert within the tongue, running along its length. They are the superior longitudinal muscle, the inferior longitudinal muscle, the vertical muscle, and the transverse muscle. These muscles alter the shape of the tongue by lengthening and shortening it, curling and uncurling its apex and edges as in tongue rolling, and flattening and rounding its surface. This provides shape and helps facilitate speech, swallowing, and eating.[8]

The superior longitudinal muscle runs along the upper surface of the tongue under the mucous membrane, and functions to shorten and curl the tongue upward. It originates near the epiglottis, at the hyoid bone, from the median fibrous septum.

The inferior longitudinal muscle lines the sides of the tongue, and is joined to the styloglossus muscle. It functions to shorten and curl the tongue downward.

The vertical muscle is located in the middle of the tongue, and joins the superior and inferior longitudinal muscles. It functions to flatten the tongue.

The transverse muscle divides the tongue at the middle, and is attached to the mucous membranes that run along the sides. It functions to lengthen and narrow the tongue.

Blood supply

[edit]

The tongue receives its blood supply primarily from the lingual artery, a branch of the external carotid artery. The lingual veins drain into the internal jugular vein. The floor of the mouth also receives its blood supply from the lingual artery.[8] There is also a secondary blood supply to the root of tongue from the tonsillar branch of the facial artery and the ascending pharyngeal artery.

An area in the neck sometimes called the Pirogov triangle is formed by the intermediate tendon of the digastric muscle, the posterior border of the mylohyoid muscle, and the hypoglossal nerve.[9][10] The lingual artery is a good place to stop severe hemorrhage from the tongue.

Nerve supply

[edit]Innervation of the tongue consists of motor fibers, special sensory fibers for taste, and general sensory fibers for sensation.[8]

- Motor supply for all intrinsic and extrinsic muscles of the tongue is supplied by efferent motor nerve fibers from the hypoglossal nerve (CN XII), with the exception of the palatoglossus, which is innervated by the vagus nerve (CN X).[8]

Innervation of taste and sensation is different for the anterior and posterior part of the tongue because they are derived from different embryological structures (pharyngeal arch 1 and pharyngeal arches 3 and 4, respectively).[11]

- Anterior two-thirds of tongue (anterior to the vallate papillae):

- Taste: chorda tympani branch of the facial nerve (CN VII) via special visceral afferent fibers

- Sensation: lingual branch of the mandibular (V3) division of the trigeminal nerve (CN V) via general visceral afferent fibers

- Posterior one third of tongue:

- Taste and sensation: glossopharyngeal nerve (CN IX) via a mixture of special and general visceral afferent fibers

- Base of tongue

- Taste and sensation: internal branch of the superior laryngeal nerve (itself a branch of the vagus nerve, CN X)

Lymphatic drainage

[edit]The tip of tongue drains to the submental nodes. The left and right halves of the anterior two-thirds of the tongue drains to submandibular lymph nodes, while the posterior one-third of the tongue drains to the jugulo-omohyoid nodes.

Microanatomy

[edit]

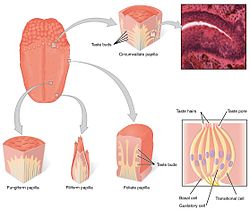

The upper surface of the tongue is covered in masticatory mucosa, a type of oral mucosa, which is of keratinized stratified squamous epithelium. Embedded in this are numerous papillae, some of which house the taste buds and their taste receptors.[12] The lingual papillae consist of filiform, fungiform, vallate and foliate papillae,[8] and only the filiform papillae are not associated with any taste buds.

The tongue can divide itself in dorsal and ventral surface. The dorsal surface is a stratified squamous keratinized epithelium, which is characterized by numerous mucosal projections called papillae.[13] The lingual papillae covers the dorsal side of the tongue towards the front of the terminal groove. The ventral surface is stratified squamous non-keratinized epithelium which is smooth.[14]

Development

[edit]

The tongue begins to develop in the fourth week of embryonic development from a median swelling – the median tongue bud (tuberculum impar) of the first pharyngeal arch.[15]

In the fifth week a pair of lateral lingual swellings, one on the right side and one on the left, form on the first pharyngeal arch. These lingual swellings quickly expand and cover the median tongue bud. They form the anterior part of the tongue that makes up two-thirds of the length of the tongue, and continue to develop through prenatal development. The line of their fusion is marked by the median sulcus.[15]

In the fourth week, a swelling appears from the second pharyngeal arch, in the midline, called the copula. During the fifth and sixth weeks, the copula is overgrown by a swelling from the third and fourth arches (mainly from the third arch) called the hypopharyngeal eminence, and this develops into the posterior part of the tongue (the other third and the posterior most part of the tongue is developed from the fourth pharyngeal arch). The hypopharyngeal eminence develops mainly by the growth of endoderm from the third pharyngeal arch. The boundary between the two parts of the tongue, the anterior from the first arch and the posterior from the third arch is marked by the terminal sulcus.[15] The terminal sulcus is shaped like a V with the tip of the V situated posteriorly. At the tip of the terminal sulcus is the foramen cecum, which is the point of attachment of the thyroglossal duct where the embryonic thyroid begins to descend.[8]

Function

[edit]Taste

[edit]Chemicals that stimulate taste receptor cells are known as tastants. Once a tastant is dissolved in saliva, it can make contact with the plasma membrane of the gustatory hairs, which are the sites of taste transduction.[16]

The tongue is equipped with many taste buds on its dorsal surface, and each taste bud is equipped with taste receptor cells that can sense particular classes of tastes. Distinct types of taste receptor cells respectively detect substances that are sweet, bitter, salty, sour, spicy, or taste of umami.[17] Umami receptor cells are the least understood and accordingly are the type most intensively under research.[18] There is a common misconception that different sections of the tongue are exclusively responsible for different basic tastes. Although widely taught in schools in the form of the tongue map, this is incorrect; all taste sensations come from all regions of the tongue, although certain parts are more sensitive to certain tastes.[19]

Mastication

[edit]The tongue is an important accessory organ in the digestive system. The tongue is used for crushing food against the hard palate, during mastication and manipulation of food for softening prior to swallowing. The epithelium on the tongue's upper, or dorsal surface is keratinised. Consequently, the tongue can grind against the hard palate without being itself damaged or irritated.[20]

Speech

[edit]The tongue is one of the primary articulators in the production of speech, and this is facilitated by both the extrinsic muscles that move the tongue and the intrinsic muscles that change its shape. Specifically, different vowels are articulated by changing the tongue's height and retraction to alter the resonant properties of the vocal tract. These resonant properties amplify specific harmonic frequencies (formants) that are different for each vowel, while attenuating other harmonics. For example, [a] is produced with the tongue lowered and centered and [i] is produced with the tongue raised and fronted. Consonants are articulated by constricting airflow through the vocal tract, and many consonants feature a constriction between the tongue and some other part of the vocal tract. For example, alveolar consonants like [s] and [n] are articulated with the tongue against the alveolar ridge, while velar consonants like [k] and [g] are articulated with the tongue dorsum against the soft palate (velum). Tongue shape is also relevant to speech articulation, for example in retroflex consonants, where the tip of the tongue is curved backward.

Intimacy

[edit]The tongue plays a role in physical intimacy and sexuality. The tongue is part of the erogenous zone of the mouth and can be used in intimate contact, as in the French kiss and in oral sex.

Clinical significance

[edit]Disease

[edit]A congenital disorder of the tongue is that of ankyloglossia also known as tongue-tie. The tongue is tied to the floor of the mouth by a very short and thickened frenulum and this affects speech, eating, and swallowing.

The tongue is prone to several pathologies including glossitis and other inflammations such as geographic tongue, and median rhomboid glossitis; burning mouth syndrome, oral hairy leukoplakia, oral candidiasis (thrush), black hairy tongue, bifid tongue (due to failure in fusion of two lingual swellings of first pharyngeal arch) and fissured tongue.

There are several types of oral cancer that mainly affect the tongue. Mostly these are squamous cell carcinomas.[21][22]

Food debris, desquamated epithelial cells and bacteria often form a visible tongue coating.[23] This coating has been identified as a major factor contributing to bad breath (halitosis),[23] which can be managed by using a tongue cleaner.

Medication delivery

[edit]The sublingual region underneath the front of the tongue is an ideal location for the administration of certain medications into the body. The oral mucosa is very thin underneath the tongue, and is underlain by a plexus of veins. The sublingual route takes advantage of the highly vascular quality of the oral cavity, and allows for the speedy application of medication into the cardiovascular system, bypassing the gastrointestinal tract. This is the only convenient and efficacious route of administration (apart from Intravenous therapy) of nitroglycerin to a patient suffering chest pain from angina pectoris.

Other animals

[edit]

The muscles of the tongue evolved in amphibians from occipital somites. Most amphibians show a proper tongue after their metamorphosis.[24] As a consequence, most tetrapod animals—amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals—have tongues (the frog family of pipids lack tongue). In mammals such as dogs and cats, the tongue is often used to clean the fur and body by licking. The tongues of these species have a very rough texture, which allows them to remove oils and parasites. Some dogs have a tendency to consistently lick a part of their foreleg, which can result in a skin condition known as a lick granuloma. A dog's tongue also acts as a heat regulator. As a dog increases its exercise the tongue will increase in size due to greater blood flow. The tongue hangs out of the dog's mouth and the moisture on the tongue will work to cool the bloodflow.[25][26]

Some animals have tongues that are specially adapted for catching prey. For example, chameleons, frogs, pangolins and anteaters have prehensile tongues.

Other animals may have organs that are analogous to tongues, such as a butterfly's proboscis or a radula on a mollusc, but these are not homologous with the tongues found in vertebrates and often have little resemblance in function. For example, butterflies do not lick with their proboscides; they suck through them, and the proboscis is not a single organ, but two jaws held together to form a tube.[27] Many species of fish have small folds at the base of their mouths that might informally be called tongues, but they lack a muscular structure like the true tongues found in most tetrapods.[28][29]

Society and culture

[edit]Figures of speech

[edit]The tongue can serve as a metonym for language. For example, the New Testament of the Bible, in the Book of Acts of the Apostles, Jesus' disciples on the Day of Pentecost received a type of spiritual gift: "there appeared unto them cloven tongues like as of fire, and it sat upon each of them. And they were all filled with the Holy Ghost, and began to speak with other tongues ....", which amazed the crowd of Jewish people in Jerusalem, who were from various parts of the Roman Empire but could now understand what was being preached. The phrase mother tongue is used as a child's first language. Many languages[30] have the same word for "tongue" and "language", as did the English language before the Middle Ages.

A common temporary failure in word retrieval from memory is referred to as the tip-of-the-tongue phenomenon. The expression tongue in cheek refers to a statement that is not to be taken entirely seriously – something said or done with subtle ironic or sarcastic humour. A tongue twister is a phrase very difficult to pronounce. Aside from being a medical condition, "tongue-tied" means being unable to say what you want due to confusion or restriction. The phrase "cat got your tongue" refers to when a person is speechless. To "bite one's tongue" is a phrase which describes holding back an opinion to avoid causing offence. A "slip of the tongue" refers to an unintentional utterance, such as a Freudian slip. The "gift of tongues" refers to when one is uncommonly gifted to be able to speak in a foreign language, often as a type of spiritual gift. Speaking in tongues is a common phrase used to describe glossolalia, which is to make smooth, language-resembling sounds that is no true spoken language itself. A deceptive person is said to have a forked tongue, and a smooth-talking person is said to have a silver tongue.

Gestures

[edit]Sticking one's tongue out at someone is considered a childish gesture of rudeness or defiance in many countries; the act may also have sexual connotations, depending on the way in which it is done. However, in Tibet it is considered a greeting.[31] In 2009, a farmer from Fabriano, Italy, was convicted and fined by Italy's highest court for sticking his tongue out at a neighbor with whom he had been arguing - proof of the affront had been captured with a cell-phone camera.[32]

Body art

[edit]Tongue piercing and splitting have become more common in western countries in recent decades.[when?] One study found that one-fifth of young adults in Israel had at least one type of oral piercing, most commonly the tongue.[33]

Representational art

[edit]Protruding tongues appear in the art of several Polynesian cultures.[34]

As food

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2022) |

The tongues of some animals are consumed and sometimes prized as delicacies. Hot-tongue sandwiches frequently appear on menus in kosher delicatessens in America. Taco de lengua (lengua being Spanish for tongue) is a taco filled with beef tongue, and is especially popular in Mexican cuisine. As part of Colombian gastronomy, Tongue in Sauce (Lengua en Salsa) is a dish prepared by frying the tongue and adding tomato sauce, onions and salt. Tongue can also be prepared as birria. Pig and beef tongue are consumed in Chinese cuisine. Duck tongues are sometimes employed in Sichuan dishes, while lamb's tongue is occasionally employed in Continental and contemporary American cooking. Fried cod "tongue" is a relatively common part of fish meals in Norway and in Newfoundland. In Argentina and Uruguay cow tongue is cooked and served in vinegar (lengua a la vinagreta). In the Czech Republic and in Poland, a pork tongue is considered a delicacy, and there are many ways of preparing it. In Eastern Slavic countries, pork and beef tongues are commonly consumed, boiled and garnished with horseradish or jellied; beef tongues fetch a significantly higher price and are considered more of a delicacy. In Alaska, cow tongues are among the more common. Both cow and moose tongues are popular toppings on open-top-sandwiches in Norway, the latter usually amongst hunters.

Tongues of seals and whales have been eaten, sometimes in large quantities, by sealers and whalers, and in various times and places have been sold for food on shore.[35][page needed]

Gallery

[edit]-

Human tongue

-

Spots on the tongue

See also

[edit]Further reading

[edit]- Pennisi, Elizabeth (May 26, 2023). "How the tongue shaped life on Earth". Science. 380 (6647). American Association for the Advancement of Science: 786–791. doi:10.1126/science.adi8563. PMID 37228192. Retrieved 25 June 2023.

References

[edit]![]() This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 1125 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 1125 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- ^ hednk-024—Embryo Images at University of North Carolina

- ^ Maton, Anthea; Hopkins, Jean; McLaughlin, Charles William; Johnson, Susan; Warner, Maryanna Quon; LaHart, David; Wright, Jill D. (1993). Human Biology and Health. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, US: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-981176-1.

- ^ a b "Tongue". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- ^ Kerrod, Robin (1997). MacMillan's Encyclopedia of Science. Vol. 6. Macmillan Publishing Company, Inc. ISBN 0-02-864558-8.

- ^ Nashi, Nadia (Aug 2007). "Lingual fat at autopsy". Laryngoscope. 117 (8): 1467–1473. doi:10.1097/MLG.0b013e318068b566. PMID 17592392.

- ^ Moyers, ROBERT E. (1964-07-01). "Tongue Problems and Malocclusion". Dental Clinics of North America. 8 (2): 529–539. doi:10.1016/S0011-8532(22)01989-9. ISSN 0011-8532. S2CID 248762393.

- ^ Klineberg, I. (1988-03-01). "Occlusion as the cause of undiagnosed pain". International Dental Journal. 38 (1): 19–27. ISSN 1875-595X. PMID 3290113.

- ^ a b c d e f g Drake, Richard L.; Vogl, Wayne; Mitchell, Adam W. M. (2005). Gray's anatomy for students. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Elsevier. pp. 989–995. ISBN 978-0-8089-2306-0.

- ^ "Pirogov's triangle". Whonamedit? - A dictionary of medical eponyms. Ole Daniel Enersen.

- ^ Jamrozik, T.; Wender, W. (January 1952). "Topographic anatomy of lingual arterial anastomoses; Pirogov-Belclard's triangle". Folia Morphologica. 3 (1): 51–62. PMID 13010300.

- ^ Dudek, Dr Ronald W. (2014). Board Review Series: Embryology (Sixth ed.). LWW. ISBN 978-1451190380.

- ^ Bernays, Elizabeth; Chapman, Reginald. "taste bud anatomy". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Fiore, Mariano; Eroschenko, Victor (2000). Di Fiore's atlas of histology with functional correlations (PDF). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 238. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 June 2017.

- ^ Hib, José (2001). Histología de Di Fiore: texto y atlas. Buenos Aires: El Ateneo. p. 189. ISBN 950-02-0386-3.

- ^ a b c Larsen, William J. (2001). Human embryology (Third ed.). Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Churchill Livingstone. pp. 372–374. ISBN 0-443-06583-7.

- ^ Tortora, Gerard J.; Derrickson, Bryan H. (2008). "17". Principles of Anatomy and Physiology (12th ed.). Wiley. p. 602. ISBN 978-0470084717.

- ^ Silverhorn, Dee Unglaub (2009). "10". Human Physiology: An integrated approach (5th ed.). Benjamin Cummings. p. 352. ISBN 978-0321559807.

- ^ Schacter, Daniel L.; Gilbert, Daniel Todd; Wegner, Daniel M. (2009). "Sensation and Perception". Psychology (2nd ed.). New York: Worth. p. 166. ISBN 9780716752158.

- ^ O'Connor, Anahad (November 10, 2008). "The Claim: The tongue is mapped into four areas of taste". The New York Times. Retrieved June 24, 2011.

- ^ Atkinson, Martin E. (2013). Anatomy for Dental Students (4th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199234462.

the tongue is also responsible for the shaping of the bolus as food passes from the mouth to the rest of the alimentary canal

- ^ "Oral Cancer Facts". The Oral Cancer Foundation. 28 August 2017. Archived from the original on 22 June 2013. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- ^ Lam, L.; Logan, R. M.; Luke, C. (March 2006). "Epidemiological analysis of tongue cancer in South Australia for the 24-year period, 1977-2001" (PDF). Australian Dental Journal. 51 (1): 16–22. doi:10.1111/j.1834-7819.2006.tb00395.x. hdl:2440/22632. PMID 16669472.

- ^ a b Newman, Michael G.; Takei, Henry; Klokkevold, Perry R.; Carranza, Fermin A. (2012). Carranza's Clinical Periodontology (11th ed.). St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier/Saunders. pp. 84–96. ISBN 978-1-4377-0416-7.

- ^ Iwasaki, Shin-ichi (July 2002). "Evolution of the structure and function of the vertebrate tongue". Journal of Anatomy. 201 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1046/j.1469-7580.2002.00073.x. ISSN 0021-8782. PMC 1570891. PMID 12171472.

- ^ "A Dog's Tongue". DrDog.com. Dr. Dog Animal Health Care Division of BioChemics. 2014. Archived from the original on 2010-09-20. Retrieved 2007-03-09.

- ^ Krönert, H.; Pleschka, K. (January 1976). "Lingual blood flow and its hypothalamic control in the dog during panting". Pflügers Archiv: European Journal of Physiology. 367 (1): 25–31. doi:10.1007/BF00583652. ISSN 0031-6768. PMID 1034283. S2CID 23295086.

- ^ Richards, O. W.; Davies, R. G. (1977). Imms' General Textbook of Entomology: Volume 1: Structure, Physiology and Development, Volume 2: Classification and Biology. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 0-412-61390-5.

- ^ Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, Philadelphia: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 298–299. ISBN 0-03-910284-X.

- ^ Kingsley, John Sterling (1912). Comparative anatomy of vertebrates. P. Blackiston's Son & Co. pp. 217–220. ISBN 1-112-23645-7.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Afrikaans tong; Danish tunge; Albanian gjuha; Armenian lezu (լեզու); Greek glóssa (γλώσσα); Irish teanga; Manx çhengey; Latin and Italian lingua; Catalan llengua; French langue; Portuguese língua; Spanish lengua; Romanian limba; Bulgarian ezik (език); Polish język; Russian yazyk (язык); Czech and Slovak jazyk; Slovene and Serbo-Croatian jezik (језик); Kurdish ziman (زمان); Persian and Urdu zabān (زبان); Arabic lisān (لسان); Aramaic liššānā (ܠܫܢܐ/לשנא); Hebrew lāšon (לָשׁוֹן); Maltese ilsien; Estonian keel; Finnish kieli; Hungarian nyelv; Azerbaijani and Turkish dil; Kazakh and Khakas til (тіл)

- ^ Dresser, Norine (8 November 1997). "On Sticking Out Your Tongue". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 18 July 2022.

- ^ United Press International (19 December 2009). "Sticking out your tongue ruled illegal". Rome, Italy. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- ^ Liran, Levin; Yehuda, Zadik; Tal, Becker (December 2005). "Oral and dental complications of intra-oral piercing". Dent Traumatol. 21 (6): 341–3. doi:10.1111/j.1600-9657.2005.00395.x. PMID 16262620.

- ^

Teilhet-Fisk, Jehanne, ed. (1973) [1973]. Dimensions of Polynesia: Fine Arts Gallery of San Diego, October 7-November 25, 1973. Fine Arts Gallery of San Diego. p. 115. Retrieved 15 April 2024.

The mouth forms of Polynesia are expressive and contain a great deal of variation, from the snarling lips of Hawaiian sculture to the tight-lipped, pursed mouths of the Easter Island statues. [...] The presence or absence of a tongue is helpful in considering the meaning of the mouth forms. The mouth forms showing protrusion of the tongue occur in the Marginal Islands (New Zealand, Hawaii, and the Marquesas), Central Polynesia (Tahiti and the Cook Islands) and the Australs.

- ^ Hawes, Charles Boardman (1924). Whaling. Doubleday.

External links

[edit]Tongue

View on GrokipediaEtymology and Overview

Etymology

The English word "tongue" derives from Old English tunge, meaning both the anatomical organ and speech or language, which in turn stems from Proto-Germanic *tungō, denoting the tongue as an organ of taste and articulation.[3] This Proto-Germanic form traces back to the Proto-Indo-European root *dn̥ǵʰwéh₂s, reconstructed as referring to the tongue in its physical and linguistic senses, evoking the organ's role in forming words and sounds.[4] Cognates in other Indo-European languages highlight this shared heritage; for instance, Latin lingua (tongue, language) evolved from Old Latin dingua, directly from the same PIE root *dn̥ǵʰwéh₂s, influencing modern terms like "linguistics" and underscoring the historical fusion of anatomy and verbal expression.[5] In contrast, the Ancient Greek term glōssa (tongue, language) originates from a separate PIE root *glṓgʰs or *gl̥gʰós, possibly meaning "pointed" or "prickly," reflecting the organ's shape rather than its phonetic function, though it similarly extended to denote speech and dialects.[6] Over time, the word's meaning shifted to emphasize its linguistic connotations, particularly in ancient medical and philosophical texts where the tongue symbolized articulation and communication. In the Hippocratic Corpus (circa 400 BCE), the tongue is linked to speech impediments, such as stuttering attributed to its dryness, which hindered clear enunciation, and observations of inarticulate speech accompanying tongue inflammation or paralysis in epidemic cases.[7][8] These associations appear in treatises like Epidemics, where symptoms like a red, parched tongue correlate with disrupted verbal output, portraying the organ as essential to human discourse beyond mere mastication.[8] Such descriptions influenced later Greco-Roman views, with physicians like Galen (2nd century CE) distinguishing the tongue's articulatory role from laryngeal voice production, reinforcing its etymological tie to language in medical discourse.[9] In medical nomenclature, terminology evolved from these classical roots into standardized modern forms, blending Greek and Latin elements for precision. Ancient Greek glōssa gave rise to terms like glōssitis (tongue inflammation), while Latin lingua informed anatomical descriptors in Renaissance texts, such as Andreas Vesalius's 1543 De Humani Corporis Fabrica, which detailed the tongue's structure in relation to speech mechanisms.[10] By the 19th century, as medical English incorporated Greco-Latin hybrids, "tongue" retained its Old English base but integrated derivatives like "glossopharyngeal" (tongue-throat nerve), reflecting a shift from descriptive humoral observations to anatomically focused naming conventions in clinical practice.[11] This progression mirrors broader trends in medical terminology, where 75% of contemporary terms derive from ancient Greek sources like those of Hippocrates, adapting "tongue"-related words to denote both pathology and physiology.[12]General Characteristics

The tongue is a muscular hydrostat, an incompressible organ composed of densely interwoven intrinsic and extrinsic muscles without rigid skeletal support, enabling precise shape changes and mobility essential for feeding, sensory perception, and in mammals, speech production across vertebrates.[13] This structure allows for functions such as prey prehension, food transport, and swallowing in tetrapods, while housing taste buds for chemical detection that supports gustatory perception.[14] In mammals, the tongue's agility further facilitates vocalization and communication by modulating airflow and sound articulation.[1] In its basic composition, the tongue divides into an anterior oral part, forming the forward two-thirds involved in manipulation and taste, and a posterior pharyngeal part, comprising the rear one-third associated with swallowing initiation, with the V-shaped terminal sulcus marking their boundary.[1] Human tongues average approximately 9–10 cm in length and weigh 70–100 grams, with variations influenced by sex, age, and individual anatomy.[15] Evolutionarily, the tongue originated as rudimentary chemosensory organs in early vertebrates like agnathans, primarily for detecting environmental chemicals without true muscular mobility, and progressively adapted into a versatile manipulator in tetrapods and mammals through developments in epithelial keratinization, muscle layering, and papillae specialization for enhanced food handling and sensory acuity.[14] Across vertebrates, it universally supports food manipulation and taste detection, while in advanced forms like mammals, it extends to communication via grooming, lapping, and sound production.[13]Human Anatomy

Macroscopic Structure

The human tongue is a muscular hydrostat that forms part of the floor of the oral cavity, divided by the V-shaped sulcus terminalis into an anterior two-thirds (oral tongue) and a posterior one-third (pharyngeal tongue).[1] Its dorsal surface is rough and covered by stratified squamous epithelium populated with lingual papillae, while the ventral surface is smoother and more vascular.[16] The tongue's overall mobility arises from its intrinsic and extrinsic musculature, enabling functions such as speech, swallowing, and mastication without skeletal attachments.[17] The dorsal surface features four types of papillae distributed across its regions. Filiform papillae, the most numerous and thread-like, cover the anterior two-thirds and provide a rough texture for food manipulation without containing taste buds.[16] Fungiform papillae, mushroom-shaped and scattered mainly on the anterior and lateral surfaces, house taste buds on their superior aspects.[1] Foliate papillae appear as vertical folds along the posterolateral borders near the sulcus terminalis, also bearing taste buds.[16] Circumvallate papillae, the largest type, form an inverted V-shaped row of 8-12 large, dome-shaped structures anterior to the sulcus terminalis, surrounded by a moat-like trench and rich in taste buds.[1] The ventral surface is attached to the floor of the mouth by the midline lingual frenulum, a fold of mucous membrane that restricts excessive protrusion while allowing mobility.[18] Lateral to the frenulum lie the sublingual folds (plica sublingualis), which contain the openings of the submandibular and sublingual salivary glands, and prominent lingual veins that drain blood from the tongue.[16] The tongue's musculature consists of intrinsic and extrinsic components, interwoven in a complex, fiber-tract arrangement without clear fascial planes. Intrinsic muscles, confined entirely within the tongue, include superior and inferior longitudinal fibers (which shorten and curl the tongue), transverse fibers (which narrow and elongate it), and vertical fibers (which flatten and widen it), all serving to alter the tongue's shape.[17] Extrinsic muscles originate outside the tongue to anchor and position it: the genioglossus fans from the mandible to protrude and depress the tongue; the hyoglossus retracts and depresses it from the hyoid bone; the styloglossus elevates and retracts it from the styloid process; and the palatoglossus elevates the posterior tongue from the soft palate.[1] Blood supply to the tongue is primarily via the lingual artery, a branch of the external carotid artery, which divides into dorsal lingual, sublingual, and deep lingual branches to perfuse the musculature and mucosa.[17] Venous drainage occurs through the lingual veins, which accompany the artery and empty into the internal jugular vein.[16] The tongue's highly vascular nature leads to profuse bleeding when bitten or otherwise injured.[19] Motor innervation is provided by the hypoglossal nerve (cranial nerve XII) to all intrinsic and extrinsic muscles except the palatoglossus, which receives innervation from the vagus nerve (cranial nerve X) via the pharyngeal plexus.[18] Sensory innervation varies by region: general sensation to the anterior two-thirds comes from the lingual nerve (a branch of the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve, CN V), while the posterior one-third is supplied by the glossopharyngeal nerve (CN IX); taste sensation to the anterior two-thirds is via the chorda tympani (branch of the facial nerve, CN VII), and to the posterior via CN IX and the vagus nerve (CN X).[1] Lymphatic drainage follows a rich, bidirectional network divided into marginal, central, and basal pathways, ultimately converging on submental, submandibular, and deep cervical lymph nodes.[17] The anterior tip and margins drain to submental and submandibular nodes, the central body to jugulo-omohyoid nodes, and the posterior base directly to deep cervical nodes.[18] A midline lingual septum, composed of dense fibrous tissue extending from the tip to the hyoid bone, partially separates the left and right halves of the tongue, contributing to its bilateral symmetry and coordinated movement.[16]Microscopic Structure

The human tongue's epithelium consists of stratified squamous cells, with the dorsal surface featuring a partially keratinized layer adapted for mechanical protection against abrasion during mastication, while the ventral surface is non-keratinized to facilitate flexibility and moisture retention.[20][21] This epithelial variation reflects the tongue's dual roles in sensory perception and propulsion of food, with the keratinized dorsal regions exhibiting thicker cornified layers compared to the thinner, more pliable ventral mucosa.[21] Taste buds, the primary chemosensory structures, are embedded within the epithelium of fungiform, foliate, and circumvallate papillae on the tongue's dorsal surface, numbering approximately 2,000 to 8,000 in adults.[22][23] Each taste bud forms an onion-shaped barrel-like complex of 50 to 150 cells, including specialized gustatory (taste receptor) cells that detect chemical stimuli via microvilli extending into the taste pore, supporting cells that provide structural integrity and insulation, and basal cells that serve as progenitors for renewal.[22][24] These components enable the transduction of taste signals, with gustatory cells regenerating every 10 to 14 days to maintain functionality.[24] Lingual glands, classified as minor salivary glands, are distributed throughout the tongue's submucosa and include serous von Ebner's glands located near the circumvallate papillae, which secrete a watery fluid rich in lingual lipase to initiate lipid digestion and clear the taste grooves for renewed sensory input.[25][26] In contrast, mucous lingual glands, found primarily in the anterior and posterior regions, produce viscous mucins for lubrication, protecting the epithelium from desiccation and aiding in bolus formation during swallowing.[25] This dual glandular system ensures both enzymatic support for digestion and maintenance of a moist oral environment essential for mucosal health.[26] The tongue's musculature comprises intrinsic skeletal muscle fibers organized into interlacing bundles arranged in longitudinal, transverse, and vertical planes, lacking the typical fascial septa found in other skeletal muscles to allow for the organ's high flexibility and precise shaping.[27] These fibers, derived from occipital somites, enable the tongue's complex movements without rigid compartmentalization, supported by a central fibrous lingual septum that provides tensile strength.[27] Beneath the epithelium lies the lamina propria, a layer of loose connective tissue rich in collagen and elastin fibers that anchors the mucosa and houses minor blood vessels, lymphatics, and sensory nerve endings.[21] Deeper still, the submucosa forms a fibrocollagenous matrix containing larger vasculature and nerves, including branches of the lingual nerve and hypoglossal nerve, which supply innervation and nutrient distribution to sustain the tongue's metabolic demands.[21][27] This connective framework integrates with the overlying epithelium to form a resilient yet adaptable tissue barrier. The tongue harbors a diverse microbiome dominated by bacteria such as Streptococcus species (comprising up to 44-66% of mucosal communities) and Veillonella, which contribute to oral homeostasis by modulating pH, competing with pathogens, and aiding in nitrate reduction for nitric oxide production that supports vascular health.[28][29] These commensals play a protective role in preventing dysbiosis, but imbalances—such as overgrowth of opportunistic anaerobes—can lead to conditions like halitosis or candidiasis, underscoring their influence on local oral ecology. Post-2020 research highlights links between tongue microbiome dysbiosis and systemic diseases, including cardiovascular inflammation via endothelial dysfunction and exacerbated COVID-19 severity through altered microbial-immune interactions.[30][31] For instance, reduced Streptococcus diversity has been associated with heightened systemic inflammatory markers in chronic conditions like atherosclerosis.[30] Lingual tissues exhibit notable regenerative potential, driven by stem cell niches in the basal layer of the stratified epithelium, where K14+ progenitor cells differentiate into both non-taste keratinocytes and taste bud lineages to facilitate rapid turnover and repair following injury.[32] These niches, influenced by signaling pathways like Wnt/Notch, support homeostasis and regeneration of the taste epithelium, with basal cells acting as multipotent progenitors that enhance recovery after nerve damage or ablation.[33] Recent studies emphasize their role in organoid cultures, offering insights into therapeutic applications for epithelial restoration in oral pathologies.[32]Development

Embryological Origins

The development of the human tongue begins around the fourth week of gestation, originating primarily from the first, third, and fourth pharyngeal (branchial) arches. These arches contribute to the formation of the tongue's mucosal covering and associated structures, with the first arch giving rise to the anterior two-thirds and the third and fourth arches contributing to the posterior one-third.[34][35] By this stage, endodermal thickenings in the floor of the primitive pharynx proliferate to form the initial tongue primordia, setting the foundation for its dual role as a muscular and sensory organ.[36] The anterior portion of the tongue arises from the tuberculum impar, a median elevation in the midline just rostral to the foramen cecum, and paired lateral lingual swellings that emerge from the first pharyngeal arch. These lateral swellings rapidly overgrow the tuberculum impar and fuse in the midline during the fifth week, establishing the bulk of the anterior tongue mucosa while leaving a subtle median sulcus as a remnant of the fusion line.[34][36] In contrast, the posterior one-third of the tongue develops from the hypobranchial eminence, a midline swelling derived from the third and fourth pharyngeal arches, which grows rostrally to merge with the anterior components by the end of the eighth week.[35][34] The musculature of the tongue originates from myoblasts in the occipital somites, which begin migrating ventrally toward the tongue primordia around the fifth week via pathways associated with the developing tongue buds. These myogenic cells, guided by the hypoglossal nerve (cranial nerve XII), differentiate into the intrinsic and extrinsic tongue muscles by the tenth week, forming a unique fibromuscular structure unanchored to bone.[34][37] Innervation of the tongue establishes concurrently during weeks 5 through 7, with nerve fibers from multiple cranial nerves extending into the developing structure. Sensory innervation to the anterior two-thirds is provided by the lingual branch of the trigeminal nerve (CN V) and chorda tympani of the facial nerve (CN VII) for taste, while the posterior one-third receives input from the glossopharyngeal nerve (CN IX) for general sensation and taste, and the vagus nerve (CN X) via its superior laryngeal branch for the root. Motor innervation is supplied by the hypoglossal nerve (CN XII) to all tongue muscles except the palatoglossus.[34][35] Incomplete fusion of the embryonic components can lead to congenital anomalies, such as bifid tongue, where failure of the lateral lingual swellings to merge results in a cleft or forked appearance at the tip, often as an isolated defect or associated with syndromes like Opitz G/BBB.[34][38]Postnatal Development

Following birth, the human tongue undergoes rapid postnatal growth, approximately doubling in length, width, and thickness by adolescence to accommodate increasing functional demands.[39] At birth, the tongue is relatively long and flat, facilitating initial suckling through coordinated muscle actions involving the intrinsic and extrinsic musculature.[40] This early phase features swift enhancements in muscle coordination, enabling transitions from reflexive suckling to more volitional movements essential for early speech babbling and feeding.[41] During childhood, the tongue continues to elongate and strengthen, with notable increases in overall length around age six, supporting advanced mastication and precise articulation for speech development.[42] Lingual papillae, including fungiform and filiform types, mature progressively, with taste buds achieving functional homeostasis through ongoing cell renewal that refines sensory capabilities.[43] These changes enhance textural discrimination and bolus formation during chewing. In adulthood, the tongue reaches peak functionality, with optimal strength and endurance for swallowing, speaking, and manipulating food.[44] Minor adaptations occur in response to habitual use, such as increased tongue force from regular exercise or masticatory demands, reflecting use-dependent muscle remodeling similar to other skeletal muscles.[45] Hormonal surges during puberty contribute to this continued growth phase, integrating with overall craniofacial maturation.[39] With aging, the tongue experiences atrophy, particularly after age 70, leading to reduced strength and slower contraction speeds, with evidence of fiber type shifts and progressive fibrosis in tongue muscles contributing to impaired mobility and coordination.[46][47] Recent studies as of 2024 indicate that tongue volume declines with age, particularly in those over 60, and there are age-related changes in tongue-jaw kinematics that may impair coordination during feeding and swallowing.[48][49] Taste sensitivity diminishes after age 60, accompanied by decreased saliva production that affects lubrication and sensory acuity.[50] These alterations link to broader sarcopenia.[44] Postnatal tongue development is influenced by nutritional status, which supports muscle hypertrophy and overall size gains, as well as hormonal fluctuations like those in puberty that drive elongation.[39] Environmental exposures, including dietary habits, can modulate muscle adaptations through varying mechanical loads during mastication.[51] Recent studies highlight age-related shifts in the tongue microbiome, with increased dysbiosis in older adults—characterized by reduced diversity and proliferation of opportunistic pathogens—potentially compromising oral health homeostasis.[52][53][54]Physiology

Sensory Functions

The tongue serves as the primary organ for gustation, the sense of taste, through specialized chemosensory structures known as taste buds embedded in lingual papillae. These taste buds detect five basic taste modalities—sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami—via distinct receptor mechanisms. Sweet, bitter, and umami tastes are mediated by G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) expressed on type II taste receptor cells, where ligands such as sugars, bitter compounds, and amino acids like glutamate activate signaling cascades involving phospholipase C and transient receptor potential channels to generate depolarization. In contrast, sour taste is detected through ionotropic receptors sensitive to protons (H+ ions) on type III cells, while salty taste primarily involves epithelial sodium channels (ENaC) that allow sodium ion influx, leading to direct depolarization.[55][56][55] The distribution of taste sensitivities across the tongue's papillae shows some regional specialization, though all modalities are represented throughout. Fungiform papillae, located primarily on the anterior tongue, are particularly sensitive to sweet and salty tastes due to their higher density of corresponding receptor-expressing cells. Circumvallate and foliate papillae, situated at the posterior and lateral edges respectively, exhibit greater responsiveness to bitter and umami stimuli, aiding in the detection of potentially harmful or nutritious compounds in food. This arrangement, while not strictly segregated as once thought, enhances the tongue's ability to sample diverse chemical profiles during ingestion. The taste buds housing these receptors, as detailed in the microscopic structure of the tongue, consist of 50–100 cells each, including receptor and supporting types that renew every 10–14 days.[22][57][22] Beyond gustation, the tongue contributes to mechanoreception, detecting touch, pressure, and texture through mechanosensitive afferents innervated by the lingual branch of the trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V). These low-threshold mechanoreceptors, expressing channels like Piezo2, enable fine discrimination of food consistency, such as crispness or smoothness, which integrates with taste for overall flavor perception. Thermoreception, involving detection of temperature changes, and nociception, the sensing of painful thermal or chemical irritants, are also mediated by trigeminal nociceptors, including transient receptor potential vanilloid (TRPV) channels that respond to extremes like hot spices or cold substances. These somatosensory functions protect the oral cavity while enhancing sensory discrimination during eating.[58][59][59] Gustatory and somatosensory signals from the tongue converge centrally for integration. Taste afferents travel via the facial (VII), glossopharyngeal (IX), and vagus (X) nerves to the rostral nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) in the medulla, where first-order neurons synapse. From the NTS, second-order projections relay to the parabrachial nucleus in rodents or directly to the ventral posteromedial thalamic nucleus in primates, and subsequently to the gustatory cortex in the insula for conscious perception and hedonic evaluation. This pathway allows multisensory synthesis, including cross-modal interactions where olfactory inputs from the retronasal route amplify taste intensity, contributing to the complex experience of flavor.[60][60][61] Individual variations in tongue sensory functions arise from genetic and age-related factors. Polymorphisms in the TAS2R38 gene, which encodes a bitter taste receptor, determine sensitivity to compounds like phenylthiocarbamide (PTC); non-tasters carry loss-of-function alleles, reducing bitterness perception and influencing dietary preferences. Aging leads to a progressive decline in taste bud density and sensitivity, particularly for sweet and salty modalities, due to reduced regenerative capacity and salivary changes, affecting up to 30% of older adults. Recent research has identified a potential sixth taste modality for fat, mediated by the scavenger receptor CD36 on taste bud cells, which facilitates long-chain fatty acid detection and orosensory signaling, distinct from textural cues. These elements underscore the tongue's adaptive sensory role in nutrition and safety.[62][63][64]Motor Functions

The tongue's motor functions are essential for mechanical manipulation of food during mastication, where it coordinates with intrinsic and extrinsic muscles to position boluses between the teeth and facilitate chewing. Through cyclic movements, the tongue transports food laterally to the post-canine region for initial breakdown, then repositions the triturated material centrally while maintaining contact with the cheeks and soft palate to prevent spillage. This coordination involves the genioglossus and hyoglossus muscles for protrusion and retraction, respectively, enabling precise bolus formation essential for subsequent swallowing.[65] In deglutition, the tongue propels the bolus during the oral and pharyngeal phases, starting with posterior squeezing against the hard palate to initiate flow into the oropharynx, followed by base retraction to push the material against pharyngeal walls for esophageal entry. The oral propulsive stage relies on sequential expansion of tongue-palate contact from anterior to posterior, while the pharyngeal stage integrates hyoid elevation for airway protection. These actions are driven by extrinsic muscles like the styloglossus for elevation, ensuring efficient bolus clearance without aspiration.[65] For speech articulation, the tongue shapes the vocal tract to produce phonemes, with the tip elevating for alveolar sounds like /t/ and /d/ via precise intrinsic muscle adjustments, and the body arching for vowels to modify resonance. Motor control involves rapid, independent segment movements—such as fronting for consonants and backing for vowels—coordinated by cortical maps that encode articulatory targets for fluent production. This dexterity allows for the complex sequencing required in human language.[66][67] In intimate activities like kissing, the tongue engages in exploratory movements providing motor feedback through coordinated protrusion and retraction, enhancing social bonding via orofacial motor patterns similar to those in speech. Grooming behaviors, such as lip licking, involve subtle tongue extensions for oral hygiene, while non-verbal sounds like clicks rely on tip snapping against the palate for communicative gestures.[68] Neural control of these functions originates in the hypoglossal nucleus, where motoneurons innervate tongue muscles via cranial nerve XII, enabling fine patterns for feeding, speech, and other behaviors through somatotopic organization. Learning refines these movements via cortical plasticity, as evidenced by expanded lingual motor cortex representations following skilled training tasks. Brainstem integration with respiration ensures seamless transitions, such as from chewing to swallowing.[69][70]Clinical Significance

Congenital Disorders

Ankyloglossia, commonly known as tongue-tie, is a congenital condition characterized by a short, tight lingual frenulum that restricts tongue movement.[71] It occurs in approximately 4-11% of newborns and can lead to breastfeeding difficulties, such as poor latch and maternal nipple pain, as well as potential speech articulation issues later in life.[72] Macroglossia, or enlargement of the tongue, is another congenital anomaly often associated with genetic syndromes like Down syndrome, where it results from hypotonia and delayed development, causing protrusion and feeding challenges in affected infants.[73] In Down syndrome, macroglossia affects up to 50% of cases and contributes to airway obstruction risks.[74]Infectious Disorders

Oral thrush, caused by overgrowth of the fungus Candida albicans, presents as creamy white patches on the tongue and inner cheeks, often accompanied by redness, soreness, and a cotton-like sensation in the mouth.[75] It commonly affects infants, older adults, and immunocompromised individuals due to factors like antibiotic use or dry mouth.[76] Herpes simplex virus (HSV-1) infection can cause painful blisters or ulcers on the tongue, leading to symptoms such as tingling, burning, and difficulty eating, typically triggered by viral reactivation in the oral mucosa.[77] Dysbiosis of the oral microbiome, involving shifts in bacterial communities like increased Porphyromonas gingivalis, plays a key role in periodontitis, which can extend to tongue inflammation and tissue destruction around the lingual structures.[78]Neoplastic Disorders

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) of the tongue is a malignant neoplasm strongly linked to risk factors such as tobacco use, alcohol consumption, and human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, particularly HPV-16, which drives oncogenesis through viral integration into host DNA.[79] Symptoms include persistent ulcers, red or white patches, pain, and bleeding on the tongue, with tobacco accounting for up to 75% of cases in some populations.[80]Neurological Disorders

Dysarthria following stroke arises from neurological damage affecting the tongue's motor control, leading to slurred, slow, or weak speech due to impaired coordination of lingual muscles.[81] It occurs in about 20-50% of stroke patients, often from lesions in the brainstem or cortex, and may present with associated facial weakness.[82] Burning mouth syndrome is a neurological condition causing a persistent burning or scalding sensation on the tongue, without visible changes, potentially linked to nerve damage, hormonal alterations, or nutritional deficiencies, affecting primarily postmenopausal women.[83]Nutritional Disorders

Glossitis due to vitamin B12 deficiency involves inflammation and atrophy of the tongue papillae, resulting in a smooth, red, painful tongue and symptoms like burning sensation or loss of taste.[84] This condition stems from impaired absorption, often in pernicious anemia, and can precede systemic anemia.[85] Geographic tongue, a benign migratory condition, features map-like red patches with white borders on the tongue surface, causing intermittent discomfort or sensitivity to spicy foods, though its exact cause remains idiopathic and possibly linked to genetic or stress factors.[86] Tongue cancers, primarily OSCC, account for approximately 30-40% of all oral cavity malignancies, with an incidence rate of 3.7 new cases per 100,000 individuals annually in the United States, showing rising trends in younger adults.[87] Globally, oral cancers, including those of the tongue, result in approximately 390,000 incident cases yearly (as of 2022 estimates).[88] Recent research highlights dysbiosis in the oral microbiome's association with halitosis through volatile sulfur compound production by anaerobic bacteria and links to autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis via systemic inflammation from periodontal pathogens translocating to distant sites.[89] Advances in regenerative medicine for tongue reconstruction post-tumor resection include ongoing trials exploring stem cell-based tissue engineering, such as mesenchymal stem cells for promoting vascularization and epithelial regeneration, though clinical applications remain in early phases as of the mid-2020s.[90]Medical Applications

The tongue serves as a valuable diagnostic tool in medicine for evaluating systemic health conditions through visual and tactile examination. Pallor of the tongue mucosa is a key indicator of anemia, with studies showing it to be one of the most accurate physical signs for detecting hemoglobin levels below 9 g/dL, outperforming pallor in other sites like the conjunctiva or palms in sensitivity and specificity.[91] A coated or furry appearance on the tongue often signals dehydration, particularly in cases of reduced salivary flow or xerostomia, where it correlates with clinical signs like dry mouth and can aid in early identification among vulnerable populations such as the elderly or those with dysphagia.[92] These observations are integrated into routine physical exams, providing noninvasive clues to underlying nutritional deficiencies, infections, or metabolic imbalances without requiring laboratory tests.[84] Sublingual administration leverages the tongue's rich vascular supply under the mucosa for rapid drug absorption, bypassing hepatic first-pass metabolism and gastrointestinal degradation, which results in higher bioavailability and faster onset compared to traditional oral routes.[93] For instance, nitroglycerin tablets placed under the tongue are a standard treatment for acute angina pectoris, delivering vasodilatory effects within minutes to relieve chest pain by improving coronary blood flow.[94] This route's advantages include enhanced efficacy for emergency use and suitability for patients with swallowing difficulties, though it requires patient education to ensure proper placement and dissolution.[95] Surgical interventions involving the tongue address both malignant and congenital conditions. Glossectomy, the partial or total removal of tongue tissue, is the primary treatment for tongue cancer, particularly squamous cell carcinoma, where the extent—ranging from partial resection for early-stage T1-T2 tumors to total glossectomy for advanced cases—is determined by tumor size, depth, and lymph node involvement to achieve clear margins while preserving function.[96] Procedures like transoral approaches are used for superficial lesions, often combined with neck dissection due to high metastasis risk, followed by reconstruction to mitigate speech and swallowing deficits.[96] For ankyloglossia, or tongue-tie, frenuloplasty releases the restrictive lingual frenulum under general anesthesia, suturing the site to improve tongue mobility and address issues like breastfeeding difficulties or speech impediments in children.[97] Imaging modalities play a critical role in assessing tongue pathology. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provides detailed visualization of tongue tumors, delineating soft tissue invasion and aiding preoperative planning for cancers, while ultrasound offers real-time evaluation of tumor margins and vascularity with lower cost and no radiation exposure.[96] In sleep apnea evaluation, tongue ultrasonography measures base thickness and lingual artery distance, with cutoffs like ≥65 mm for thickness achieving 74.4% sensitivity and 61.9% specificity in screening severe obstructive cases, helping prioritize polysomnography in resource-limited settings.[98] The tongue's unique muscle composition makes it an ideal model for studying skeletal muscle regeneration. Following surgical resection for cancer or trauma, tongue tissue demonstrates robust regenerative potential through stem cell activation and myogenic pathways, informing tissue engineering strategies like autologous flaps or stem cell scaffolds to restore volume and function.[99] Electromyography (EMG), particularly high-density surface variants using intraoral electrode grids, maps motor unit activity during tasks like protrusion or articulation, revealing spatiotemporal patterns of genioglossus and intrinsic muscles to assess neuropathy or guide rehabilitation in motor disorders.[100] Recent advancements in telemedicine utilize AI for tongue image analysis to detect diseases noninvasively. Deep learning models, such as those integrating U2Net-MT segmentation and vision transformers, analyze features like color, coating, and shape from smartphone-captured images, achieving up to 86.61% accuracy in classifying conditions like gastrointestinal disorders or respiratory infections, with post-2022 developments enhancing objectivity in remote TCM-based diagnostics.[101] These systems process large datasets from clinical cohorts, supporting early detection in underserved areas by correlating tongue manifestations with systemic health markers.[101]Comparative Anatomy

In Mammals

In mammals, the tongue exhibits diverse anatomical adaptations tailored to dietary needs, environmental demands, and behavioral functions, ranging from grooming and prey capture to vocalization and filtration feeding. These variations often involve modifications in surface structures, musculature, and sensory integration, reflecting evolutionary pressures on feeding efficiency and sensory processing. While human tongues emphasize fine motor control for speech and manipulation, other mammals prioritize specialized roles such as rasping meat or stripping foliage. In carnivores, the tongue surface is characterized by rough, backward-facing papillae that enhance grooming and food processing. For instance, in felids like domestic cats and lions, the tongue is covered with hollow, sharp spines known as cavo papillae, which are keratinized structures measuring over 1 mm in height and oriented caudally to act as hooks for detangling fur and scraping meat from bones. These papillae wick saliva via capillary action in under 0.1 seconds, distributing it evenly across the fur to facilitate cleaning and evaporative cooling, with a temperature drop of approximately 5°C during grooming.[102][103] Herbivores display elongated tongues adapted for prehension and manipulation of vegetation. Giraffes possess a highly extensible and flexible tongue, up to 45-50 cm long, with a prehensile structure that enables precise grasping of leaves from thorny acacia branches, aided by thick, dark-pigmented epithelium for UV protection.[104] In contrast, anteaters feature a slender, protrusible tongue extending up to 60 cm, coated in sticky saliva from enlarged submaxillary and parotid glands, which adheres to ants and termites during rapid flicks into mounds; this hydrostatic elongation, detached from the hyoid bone, allows for snake-like probing without teeth.[105][106] Primates exhibit dexterous tongues suited for tool use and vocalization, with anatomical parallels to humans. In macaques, the tongue and associated vocal tract structures enable a full range of movements nearly identical to those in humans, including precise articulation for vowel sounds and potential sentence formation, though limited by neural control rather than anatomy. This dexterity supports foraging manipulations and complex grooming, facilitating social bonding through vocal and manual interactions.[107] Marine mammals show reduced tongue prominence in some lineages, emphasizing filtration over mastication. Baleen whales, such as those in the Balaenopteridae family (e.g., humpback and blue whales), have flaccid, elastic tongues composed of connective tissues like elastin and collagen, weighing up to several tons and invaginating into a ventral pouch to engulf massive volumes of water (80,000–100,000 liters) during lunge feeding; the tongue then contracts via the genioglossus muscle to expel water through baleen plates while retaining prey. In contrast, odontocetes like dolphins retain more mobile tongues for prey transport, but mysticetes overall lack teeth and use the tongue primarily for hydrodynamic flow rather than sensory or manipulative roles.[13][108] Muscle configurations vary significantly in extrinsic attachments to support specialized feeding. Across mammals, extrinsic muscles like the genioglossus and hyoglossus anchor the tongue to the hyoid and mandible, enabling protrusion and retraction; in pigs, for example, the hyoglossus enlarges proportionally during the suckling-to-drinking transition (from 0.016 to 0.030 relative size), with altered firing patterns to facilitate lapping, while the genioglossus shows increased activity for anteroposterior movements. These variations allow hydrostatic shaping in herbivores for elongation and rigid control in carnivores for rasping.[109] Sensory adaptations in mammals often integrate taste with olfaction for enhanced flavor perception. In dogs, the tongue's approximately 1,700 taste buds work in concert with a superior olfactory system (220 million receptors versus 5 million in humans), where licking transports volatiles to the vomeronasal organ via the flehmen response, allowing multisensory integration of taste and smell to assess food palatability and detect environmental cues.[110][111]In Non-Mammals

In non-mammalian vertebrates and select invertebrates, the tongue exhibits remarkable diversity in structure and function, often adapted to specific ecological niches such as chemosensory detection, prey capture, or food processing, contrasting with the more generalized mammalian forms. These variations highlight adaptations to ectothermic lifestyles and aquatic or terrestrial environments, where tongues may serve as sensory appendages, projectile mechanisms, or rudimentary manipulators rather than primary manipulators of solid food.[14] In reptiles, the tongue is frequently elongated and forked, particularly in snakes, where it functions as a chemosensory organ for detecting airborne chemical cues. The forked tip allows for stereoscopic olfaction by sampling scents from two points simultaneously, delivering them via tongue flicking to the vomeronasal organ, also known as Jacobson's organ, located in the roof of the mouth. This mechanism enables precise localization of prey or mates, with the bifurcation enhancing directional sensitivity to pheromone trails.[112][113] Birds typically possess a tongue that is reduced or vestigial in many species, particularly in ground-foraging or granivorous birds like ratites, where it plays a minimal role in feeding and is often a simple, immobile flap aiding in swallowing. However, in woodpeckers, the tongue is highly specialized and protractile, extending up to four times the beak length through a hyoid apparatus that wraps around the skull, allowing it to probe deep into tree crevices for insects. This structure features backward-facing barbs and sticky mucus for extracting prey, demonstrating a hydrostatically driven elongation powered by elastic recoil and muscle contraction.[14][114][115] In fish, the tongue is generally absent or non-protrusible, consisting of a fleshy basal pad that primarily supports the gill arches rather than manipulating food externally. Many bony fish compensate with pharyngeal jaws—specialized tooth-bearing structures in the throat—for grinding and processing prey internally, as seen in cichlids where these jaws independently crush algae or small organisms. This internal adaptation reflects the aquatic environment's emphasis on suction feeding over tongue-based manipulation.[13][116] Amphibians, such as frogs, feature a highly adhesive and protrusible tongue specialized for rapid prey capture, projecting ballistically at speeds up to 4 m/s in some species through hydrostatic muscle action and elastic energy storage in the tongue pad. The tongue's mucus-covered surface creates wet adhesion via capillary forces, securing insects or small vertebrates upon impact, with retraction powered by retractor muscles pulling the prey into the mouth. This mechanism exemplifies an evolutionary refinement for terrestrial ambush predation.[117][118][119] Among invertebrates, mollusks employ a radula—a chitinous, ribbon-like structure analogous to a tongue—for rasping and scraping food, with thousands of microscopic teeth arranged in rows that wear down surfaces like algae on rocks or boring into shells. In gastropods, the radula moves via odontophore muscles, enabling both grazing and predatory drilling. Insects, conversely, utilize a proboscis, a tubular extension of the mouthparts for liquid feeding, as in butterflies where it uncoils to siphon nectar, with fluid dynamics governed by suction pumps and surface tension. These structures underscore invertebrate innovations in microphagy and fluid intake.[120][121][122][123] Evolutionarily, non-mammalian tongues trace from simple epithelial flaps in early jawed fishes, serving passive roles in oral cavity support, to more complex muscular hydrostats in amphibians and reptiles, where volume-conserving deformations enable projection and sensory sampling. This progression reflects selective pressures for enhanced feeding efficiency in diverse habitats, culminating in the versatile, innervated structures of higher vertebrates.[14]Cultural Aspects

Linguistic and Symbolic Uses

In human language, the tongue frequently serves as a metonym for speech and language itself, encapsulating the organ's role in articulation and expression. The term "mother tongue," for instance, denotes one's native language, evoking the intimate, formative connection to one's first mode of communication acquired from caregivers.[124] This usage underscores how the tongue symbolizes linguistic identity and heritage across cultures. Numerous idioms draw on the tongue to convey interpersonal dynamics and verbal prowess. A "sharp tongue" refers to a tendency toward critical or sarcastic speech, often implying wit that borders on harshness.[125] Similarly, in Chinese, the term 毒舌 (dú shé) denotes a sharp-tongued or venomous tongue, referring to a person inclined to make acerbic comments that may hurt others' feelings.[126] Conversely, a "silver tongue" describes eloquent, persuasive oratory capable of charming or convincing others.[127] These expressions highlight the tongue's metaphorical association with the cutting edge of words or their smooth allure. Gestures involving the tongue also carry expressive weight in social interactions. Sticking out the tongue often signals mockery, playfulness, or disdain, as seen in children's taunts or athletes' displays of concentration during intense focus.[128] In some contexts, it conveys disgust or rejection, rooted in primal nonverbal cues. Symbolically, the tongue appears in religious and folkloric traditions as an emblem of deceit or temptation. In Christian iconography, the serpent's forked tongue represents duplicity and malice, drawing from biblical depictions of the snake in Genesis as a cunning deceiver whose speech leads to downfall.[129] This motif extends to warnings about the human tongue's potential for harm, likened in Psalms to a serpent's sharp venom.[130] Cross-culturally, tongue protrusion holds varied significance. In Māori tradition, during the haka—a ceremonial dance of challenge and unity—men extend their tongues (known as whētero) to project ferocity and intimidation, symbolizing strength and defiance toward adversaries.[131] This gesture amplifies the performers' communal pride and readiness. In contemporary digital culture, the tongue emoji (👅) has evolved into a versatile symbol on social media platforms. It commonly denotes playfulness, silliness, or jesting, but frequently implies flirtation or teasing innuendo, especially in informal exchanges among younger users since the 2010s.[132][133]Artistic and Culinary Roles