Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Anomic aphasia

View on Wikipedia| Anomic aphasia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Dysnomia, nominal aphasia |

| |

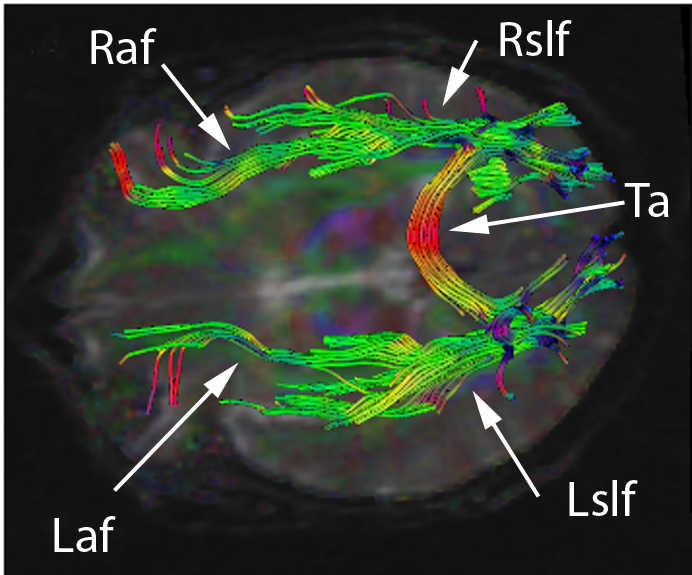

| Diffusion tensor imaging of the brain shows the right and left arcuate fasciculus (Raf & Laf). Also shown are the right and left superior longitudinal fasciculus (Rslf & Lslf), and tapetum of corpus callosum (Ta). Damage to the Laf is known to cause anomic aphasia. | |

| Specialty | Neurology, neuropsychology |

Anomic aphasia, also known as dysnomia, nominal aphasia, and amnesic aphasia, is a mild, fluent type of aphasia where individuals have word retrieval failures and cannot express the words they want to say (particularly nouns and verbs).[1] By contrast, anomia is a deficit of expressive language, and a symptom of all forms of aphasia, but patients whose primary deficit is word retrieval are diagnosed with anomic aphasia.[2] Individuals with aphasia who display anomia can often describe an object in detail and maybe even use hand gestures to demonstrate how the object is used, but cannot find the appropriate word to name the object.[3] Patients with anomic aphasia have relatively preserved speech fluency, repetition, comprehension, and grammatical speech.

Types

[edit]- Word selection anomia is caused by damage to the posterior inferior temporal area. This type of anomia occurs when the patient knows how to use an object and can correctly select the target object from a group of objects, and yet cannot name the object. Some patients with word selection anomia may exhibit selective impairment in naming particular types of objects, such as animals or colors.[4] In the subtype known as color anomia, the patient can distinguish between colors but cannot identify them by name or name the color of an object.[5] The patients can separate colors into categories, but they cannot name them.

- Semantic anomia is caused by damage to the angular gyrus. This is a disorder in which the meaning of words becomes lost. In patients with semantic anomia, a naming deficit is accompanied by a recognition deficit. Thus, unlike patients with word selection anomia, patients with semantic anomia are unable to select the correct object from a group of objects, even when provided with the name of the target object.[4]

- Disconnection anomia results from the severing of connections between sensory and language cortices. Patients with disconnection anomia may exhibit modality-specific anomia, where the anomia is limited to a specific sensory modality, such as hearing. For example, a patient who is perfectly capable of naming a target object when it is presented via certain sensory modalities like audition or touch, may be unable to name the same object when the object is presented visually. Thus, in such a case, the patient's anomia arises as a consequence of a disconnect between their visual cortex and language cortices.[4]

- Patients with disconnection anomia may also exhibit callosal anomia, in which damage to the corpus callosum prevents sensory information from being transmitted between the two hemispheres of the brain. Therefore, when sensory information is unable to reach the hemisphere that is language-dominant (typically the left hemisphere in most individuals), the result is anomia. For instance, if patients with this type of disconnection anomia hold an object in their left hand, this somatosensory information about the object would be sent to the right hemisphere of the brain, but then would be unable to reach the left hemisphere due to callosal damage. Thus, this somatosensory information would fail to be transmitted to language areas in the left hemisphere, in turn resulting in the inability to name the object in the left hand. In this example, the patient would have no problem with naming, if the test object were to be held in the right hand. This type of anomia may also arise as a consequence of a disconnect between sensory and language cortices.[4]

- Articulatory initiation anomia results from damage to the frontal area. Characteristics of this anomia are non-fluent output, word-finding pauses, deficient word lists. Patients perform better at confrontation naming tasks, the selection of a label for a corresponding picture, than word list tasks. Patients are aided in word selection by prompting, unlike those with word selection anomia.[6]

- Phonemic substitution anomia results from damage to the inferior parietal area. Patients maintain fluent output but exhibit literal and neologistic paraphasia. Literal paraphasia is the incorrect substitution of phonemes, and neologistic paraphasia is the use of non-real words in the place of real words. Patient's naming ability is contaminated by paraphasia.[6]

- Modality-specific anomia is caused by damage to the sensory cortex, pathways to the dominant angular gyrus, or both. In these patients, word-finding is worst in one sensory modality, for example visual or tactile.[6]

Causes

[edit]Anomic aphasia, occurring by itself, may be caused by damage to almost anywhere in the left hemisphere and in some cases can be seen in instances of right hemisphere damage.[7] Anomia can be genetic or caused by damage to various parts of the parietal lobe or the temporal lobe of the brain due to traumatic injury, stroke, or a brain tumor.[8] While anomic aphasia is primarily caused by structural lesions, they may also originate in Alzheimer's disease (anomia may be the earliest language deficit in posterior cortical atrophy variant of Alzheimer's) or other neurodegenerative diseases.[7]

Although the main causes are not specifically known, many researchers have found other factors contributing to anomic aphasia. People with damage to the left hemisphere of the brain are more likely to have anomic aphasia. Broca's area, the speech production center in the brain, was linked to being the source for speech execution problems, with the use of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), now commonly used to study anomic patients.[9] Other experts believe that damage to Wernicke's area, which is the speech comprehension area of the brain, is connected to anomia because the patients cannot comprehend the words that they are hearing.[10]

Although many experts have believed that damage to Broca's area or Wernicke's area are the main causes of anomia, current studies have shown that damage in the left parietal lobe is the cause of anomic aphasia.[11] One study was conducted using a word repetition test as well as fMRI in order to see the highest level of activity as well as where the lesions are in the brain tissue.[11] Fridrikkson, et al. saw that damage to neither Broca's area nor Wernicke's area were the sole sources of anomia in the subjects. Therefore, the original anomia model, which theorized that damage occurred on the surface of the brain in the grey matter was debunked, and it was found that the damage was in the white matter deeper in the brain, on the left hemisphere.[11] More specifically, the damage was in a part of the nerve tract called the arcuate fasciculus, for which the mechanism of action is unknown, though it is known to connect the posterior (back) of the brain to the anterior (front) and vice versa.[12]

While anomic aphasia is associated with lesions throughout the left hemisphere, severe and isolated anomia has been considered a sign of deep temporal lobe or lateral temporo-occipital damage. Damage to these areas is seen in patients showing infarction limited to regions supplied by the dominant posterior cerebral artery (PCA) and is referred to as posterior cerebral artery syndrome.[13]

Diagnosis

[edit]The best way to see if anomic aphasia has developed is by using verbal and imaging tests. The combination seems to be most effective, since either test done alone may give false positives or false negatives. For example, the verbal test is used to see if a speech disorder presents, and whether the problem is in speech production or comprehension. Patients with Alzheimer's disease have speech problems linked to dementia or progressive aphasias, which can include anomia.[14][15] The imaging test, mostly done using MRI scans, is ideal for lesion mapping or viewing deterioration in the brain. However, imaging cannot diagnose anomia on its own because the lesions may not be located deep enough to damage the white matter or the arcuate fasciculus. However, anomic aphasia is very difficult to associate with a specific lesion location in the brain. Therefore, the combination of speech tests and imaging tests has the highest sensitivity and specificity.[16]

Picture-naming tests, such as the Philadelphia Naming Test (PNT), are also utilized in diagnosing aphasias. Analysis of picture-naming is compared with reading, picture categorizing, and word categorizing. There is a considerable similarity among aphasia syndromes in terms of picture-naming behavior, however anomic aphasiacs produced the fewest phonemic errors and the most multiword circumlocutions. These results suggest minimal word-production difficulty in anomic aphasia relative to other aphasia syndromes.[17]

Anomic aphasia has been diagnosed in some studies using the Aachen Aphasia Test (AAT), which tests language functioning after brain injury. This test aims to: identify the presence of aphasia; provide a profile of the speaker's language functioning according to different language modalities (speaking, listening, reading, writing) and different levels of linguistic description (phonology, morphology, semantics, and syntax); give a measure of severity of any breakdown.[18] This test was administered to patients participating in a study in 2012, and researchers found that on the naming subtest of the AAT patients showed relevant naming difficulties and tended to substitute the words they could not produce with circumlocutions.[19]

The Western Aphasia Battery is another test that is conducted with the goal of classifying aphasia subtypes and rating the severity of the aphasiac impairment. The test is composed of four language and three performance domains. Syndrome classification is determined by the pattern of performance on the four language subtests, which assess spontaneous speech, comprehension, repetition, and naming.[20]

Doing a hearing test first is important, in case the patient cannot clearly hear the words or sentences needed in the speech repetition test.[21] In the speech tests, the person is asked to repeat a sentence with common words; if the person cannot identify the word, but he or she can describe it, then the person is highly likely to have anomic aphasia. However, to be completely sure, the test is given while a test subject is in an fMRI scanner, and the exact location of the lesions and areas activated by speech are pinpointed.[11] Few simpler or cheaper options are available, so lesion mapping and speech repetition tests are the main ways of diagnosing anomic aphasia.[citation needed]

Definition

[edit]Anomic aphasia (anomia) is a type of aphasia characterized by problems recalling words, names, and numbers. Speech is fluent and receptive language is not impaired in someone with anomic aphasia.[22] Subjects often use circumlocutions (speaking in a roundabout way) to avoid a name they cannot recall or to express a certain word they cannot remember. Sometimes, the subject can recall the name when given clues. Additionally, patients are able to speak with correct grammar; the main problem is finding the appropriate word to identify an object or person.[citation needed]

Sometimes, subjects may know what to do with an object, but still not be able to give a name to the object. For example, if a subject is shown an orange and asked what it is called, the subject may be well aware that the object can be peeled and eaten, and may even be able to demonstrate this by actions or even verbal responses; however, they cannot recall that the object is called an "orange". Sometimes, when a person with this condition is multilingual, they might confuse the language they are speaking in trying to find the right word (inadvertent code-switching).[citation needed]

Management

[edit]No method is available to completely cure anomic aphasia. However, treatments can help improve word-finding skills.

Although a person with anomia may find recalling many types of words to be difficult, such as common nouns, proper nouns, verbs, etc., many studies have shown that treatment for object words, or nouns, has shown promise in rehabilitation research.[21] The treatment includes visual aids, such as pictures, and the patient is asked to identify the object or activity. However, if that is not possible, then the patient is shown the same picture surrounded by words associated with the object or activity.[23][24] Throughout the process, positive encouragement is provided. The treatment shows an increase in word finding during treatment; however, word identifying decreased two weeks after the rehabilitation period.[21] Therefore, it shows that rehabilitation effort needs to be continuous for word-finding abilities to improve from the baseline. The studies show that verbs are harder to recall or repeat, even with rehabilitation.[21][25]

Other methods in treating anomic aphasia include circumlocution-induced naming therapy (CIN), wherein the patient uses circumlocution to assist with their naming rather than just being told to name the item pictured after given some sort of cue. Results suggest that the patient does better in properly naming objects when undergoing this therapy because CIN strengthens the weakened link between semantics and phonology for patients with anomia, since they often know what an object is used for, but cannot verbally name it.[26]

Anomia is often challenging for the families and friends of those affected by it. One way to overcome this is computer-based treatment models, effective especially when used with clinical therapy. Leemann et al. provided anomic patients with computerized-assisted therapy (CAT) sessions, along with traditional therapy sessions using treatment lists of words. Some of the patients received a drug known to help relieve symptoms of anomia (levodopa), while others received a placebo. The researchers found that the drug had no significant effects on improvement with the treatment lists, but almost all of the patients improved after the CAT sessions. They concluded that this form of computerized treatment is effective in increasing naming abilities in anomic patients.[27]

Additionally, one study researched the effects of using "excitatory (anodal) transcranial direct current stimulation" over the right temporoparietal cortex, a brain area that seems to correlate to language. The electrical stimulation seemed to enhance language training outcome in patients with chronic aphasia.[28]

Contextual repetition priming treatment is a technique which involves repeated repetition of names of pictures that are related semantically, phonologically, or are unrelated. Patients with impaired access to lexical-semantic representations show no long-term improvement in naming, but patients with good access to semantics show long-term benefits.[29]

Development of self-cueing strategies can also facilitate word retrieval. Patients identify core words that can be retrieved without struggle, and establish a relationship between cue words and words that begin with the same sound but cannot be retrieved. Patients then learn to use the cue word to facilitate word retrieval for the target object.[30]

Epidemiology

[edit]Many different populations can and do have anomia. For instance, deaf patients who have had a stroke can demonstrate semantic and phonological errors, much like hearing anomic patients. Researchers have called this subtype sign anomia.[31]

Multilingual patients typically experience anomia to a greater degree in just one of their fluent languages. However, evidence conflicts as to which language – first or second – is impacted more.[32][33]

Research on children with anomia has indicated that children who undergo treatment are, for the most part, able to gain back normal language abilities, aided by brain plasticity. However, longitudinal research on children with anomic aphasia due to head injury shows that even several years after the injury, some signs of deficient word retrieval are still observed. These remaining symptoms can sometimes cause academic difficulties later on.[34]

Patients

[edit]This disorder may be extremely frustrating for people with and without the disorder. Although the persons with anomic aphasia may know the specific word, they may not be able to recall it and this can be very difficult for everyone in the conversation. Positive reinforcements are helpful.[21]

Although not many literary cases mention anomic aphasia, many nonfiction books have been written about living with aphasia. One of them is The Man Who Lost His Language by Sheila Hale. It is the story of Hale's husband, John Hale, a scholar who had had a stroke and lost speech formation abilities. In her book, Hale also explains the symptoms and mechanics behind aphasia and speech formation. She adds the emotional components of dealing with a person with aphasia and how to be patient with the speech and communication.[35][36]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Anomic Aphasia - National Aphasia Association". National Aphasia Association. Retrieved 2015-11-13.

- ^ Manasco 2014, Chapter 7: Motor Speech Disorders: The Dysarthrias..

- ^ Manasco 2014.

- ^ a b c d Devinsky, Orrin; D'Esposito, Mark (2004). Neurology of Cognitive and Behavioral Disorders (21st ed.). Oxford University Press, USA. pp. 194–196. ISBN 978-0-19-513764-4.

- ^ Mattocks, Linda; Hynd, George W. (1986). "Color anomia: Clinical, developmental, and neuropathological issues". Developmental Neuropsychology. 2 (2): 101–112. doi:10.1080/87565648609540333. ISSN 8756-5641.

- ^ a b c Benson, Frank (August 1991). "What's in a Name?". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 66 (8): 865–7. doi:10.1016/S0025-6196(12)61206-3. PMID 1861557. Retrieved 2019-12-04.

- ^ a b Swanberg, Margaret; Nasreddine, Ziad; Mendez, Mario; Cummings, Jeffrey (12 September 2007). Textbook of Clinical Neurology (3 ed.). Saunders. pp. 79–98. ISBN 9781416036180.

- ^ Woollams, AM.; Cooper-Pye, E.; Hodges, JR.; Patterson, K. (Aug 2008). "Anomia: a doubly typical signature of semantic dementia". Neuropsychologia. 46 (10): 2503–14. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.04.005. PMID 18499196. S2CID 10435463.

- ^ Fridriksson J, Moser D, Ryalls J, Bonilha L, Rorden C, Baylis G (June 2009). "Modulation of frontal lobe speech areas associated with the production and perception of speech movements". J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 52 (3): 812–9. doi:10.1044/1092-4388(2008/06-0197). PMC 2693218. PMID 18978212.

- ^ Hamilton AC, Martin RC, Burton PC (December 2009). "Converging functional magnetic resonance imaging evidence for a role of the left inferior frontal lobe in semantic retention during language comprehension". Cogn Neuropsychol. 26 (8): 685–704. doi:10.1080/02643291003665688. PMID 20401770. S2CID 9409238.

- ^ a b c d Fridriksson J, Kjartansson O, Morgan PS, et al. (August 2010). "Impaired speech repetition and left parietal lobe damage". J. Neurosci. 30 (33): 11057–61. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1120-10.2010. PMC 2936270. PMID 20720112.

- ^ Anderson JM, Gilmore R, Roper S, et al. (October 1999). "Conduction aphasia and the arcuate fasciculus: A reexamination of the Wernicke-Geschwind model". Brain and Language. 70 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1006/brln.1999.2135. PMID 10534369. S2CID 12171982.

- ^ Mohr, J.P.; Binder, Jeffrey (31 March 2011). Stroke (5th ed.). Saunders. p. 1520. ISBN 9781416054788.

- ^ Rohrer JD, Knight WD, Warren JE, Fox NC, Rossor MN, Warren JD (January 2008). "Word-finding difficulty: a clinical analysis of the progressive aphasias". Brain. 131 (Pt 1): 8–38. doi:10.1093/brain/awm251. PMC 2373641. PMID 17947337.

- ^ Harciarek M, Kertesz A (September 2011). "Primary progressive aphasias and their contribution to the contemporary knowledge about the brain-language relationship". Neuropsychol Rev. 21 (3): 271–87. doi:10.1007/s11065-011-9175-9. PMC 3158975. PMID 21809067.

- ^ Healy EW, Moser DC, Morrow-Odom KL, Hall DA, Fridriksson J (April 2007). "Speech perception in MRI scanner noise by persons with aphasia" (PDF). J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 50 (2): 323–34. doi:10.1044/1092-4388(2007/023). PMID 17463232.

- ^ Kohn, SE (1985). "Picture-naming in aphasia". Brain and Language. 24 (2). National Institutes of Health: 266–83. doi:10.1016/0093-934x(85)90135-x. PMID 3978406. S2CID 29075625.

- ^ Miller, N; Willmes, K; De Bleser, R (2000). "The psychometric properties of the English language version of the Aachen Aphasia Test (EAAT)". Aphasiology. 14 (7): 683–722. doi:10.1080/026870300410946. S2CID 144512889.

- ^ Andreetta, Sara; Cantagallo, Anna; Marini, Andrea (2012). "Narrative discourse in anomic aphasia". Neuropsychologia. 50 (8): 1787–93. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2012.04.003. PMID 22564448. S2CID 17203842.

- ^ Otfried, Spreen (1998). Acquired Aphasia (3 ed.). Elsevier Inc. pp. 71–156. ISBN 978-0-12-619322-0. Retrieved 2019-12-04.

- ^ a b c d e Wambaugh JL, Ferguson M (2007). "Application of semantic feature analysis to retrieval of action names in aphasia". J Rehabil Res Dev. 44 (3): 381–94. doi:10.1682/JRRD.2006.05.0038. PMID 18247235.

- ^ Manasco 2014, Chapter 4: The Aphasias.

- ^ Coelho, Carl A.; McHugh, Regina E.; Boyle, Mary (2000). "Semantic feature analysis as a treatment for aphasic dysnomia: A replication". Aphasiology. 14 (2): 133–142. doi:10.1080/026870300401513. ISSN 0268-7038. S2CID 143947547.

- ^ Maher LM, Raymer AM (2004). "Management of anomia". Top Stroke Rehabil. 11 (1): 10–21. doi:10.1310/318R-RMD5-055J-PQ40. PMID 14872396. S2CID 40998077.

- ^ Mätzig S, Druks J, Masterson J, Vigliocco G (June 2009). "Noun and verb differences in picture naming: past studies and new evidence". Cortex. 45 (6): 738–58. doi:10.1016/j.cortex.2008.10.003. PMID 19027106. S2CID 32070836.

- ^ Francis, Dawn R.; Clark, Nina; Humphreys, Glyn W. (2002). "Circumlocution-induced naming (CIN): A treatment for effecting generalisation in anomia?". Aphasiology. 16 (3): 243–259. doi:10.1080/02687040143000564. S2CID 144118775.

- ^ Leemann, B.; Laganaro, M.; Chetelat-Mabillard, D.; Schnider, A. (12 September 2010). "Crossover Trial of Subacute Computerized Aphasia Therapy for Anomia With the Addition of Either Levodopa or Placebo". Neurorehabilitation and Neural Repair. 25 (1): 43–47. doi:10.1177/1545968310376938. PMID 20834044. S2CID 42776933.

- ^ Flöel, A.; Meinzer, M.; Kirstein, R.; Nijhof, S.; Deppe, M.; Knecht, S.; Breitenstein, C. (Jul 2011). "Short-term anomia training and electrical brain stimulation". Stroke. 42 (7): 2065–7. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.609032. PMID 21636820.

- ^ Martin, N; Fink, R; Renvall, K; Laine, M (Nov 12, 2006). "Effectiveness of contextual repetition priming". Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 12 (6): 853–66. doi:10.1017/S1355617706061030. PMID 17064448. S2CID 22185628.

- ^ Nickels, Lyndsey (1992). "The autocue? self-generated phonemic cues in the treatment of a disorder of reading and naming". Cognitive Neuropsychology. 9 (2): 155–182. doi:10.1080/02643299208252057.

- ^ Atkinson, Marshall, J.; E. Smulovitch; A. Thacker; B. Woll (2004). "Aphasia in a user of British Sign Language: Dissociation between sign and gesture". Cognitive Neuropsychology. 21 (5): 537–554. doi:10.1080/02643290342000249. PMID 21038221. S2CID 27849117.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mendez, Mario F. (November 2001). "Language-Selective Anomia in a Bilingual Patient". The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 12 (4): 515–516. doi:10.1176/appi.neuropsych.12.4.515. PMID 11083172.

- ^ Filley, Christopher M.; Ramsberger, Gail; Menn, Lise; Wu, Jiang; Reid, Bessie Y.; Reid, Allan L. (2006). "Primary Progressive Aphasia in a Bilingual Woman". Neurocase. 12 (5): 296–299. doi:10.1080/13554790601126047. PMID 17190751. S2CID 29408307.

- ^ Van Hout, Anne (June 1992). "Acquired Aphasia in Children". Seminars in Pediatric Neurology. 4 (2): 102–108. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.973.1899. doi:10.1016/s1071-9091(97)80026-5. PMID 9195667.

- ^ Hale, Sheila. (2007). The man who lost his language : a case of aphasia. London; Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. ISBN 978-1-84310-564-0. OCLC 174143262.

- ^ Anthony Campbell. "Book Review - THE MAN WHO LOST HIS LANGUAGE". Retrieved 18 October 2013.

Sources

[edit]- Manasco, Mark (2014). Introduction to Neurogenic Communication Disorders. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning. ISBN 9780763794170. OCLC 808769513.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link)

External links

[edit] Data related to Anomic aphasia at Wikidata

Data related to Anomic aphasia at Wikidata