Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Grey matter

View on Wikipedia

| Grey matter | |

|---|---|

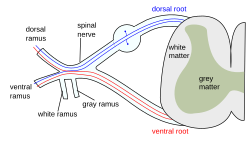

The formation of the spinal nerve from the dorsal and ventral roots (with grey matter labelled at centre right). | |

Micrograph showing grey matter, with the characteristic neuronal cell bodies (dark shade of pink), and white matter with its characteristic fine meshwork-like appearance (left of image; lighter shade of pink). HPS stain. | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | substantia grisea |

| MeSH | D066128 |

| TA98 | A14.1.00.002 A14.1.02.020 A14.1.04.201 A14.1.05.201 A14.1.05.401 A14.1.06.301 |

| TA2 | 5365 |

| FMA | 67242 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Grey matter (gray matter in American English) is a major component of the central nervous system, consisting of neuronal cell bodies, neuropil (dendrites and unmyelinated axons), glial cells (astrocytes and oligodendrocytes), synapses, and capillaries. Grey matter is distinguished from white matter in that it contains numerous cell bodies and relatively few myelinated axons, while white matter contains relatively few cell bodies and is composed chiefly of long-range myelinated axons.[1] The colour difference arises mainly from the whiteness of myelin. In living tissue, grey matter actually has a very light grey colour with yellowish or pinkish hues, which come from capillary blood vessels and neuronal cell bodies.[2]

Structure

[edit]Grey matter refers to unmyelinated neurons and other cells of the central nervous system. It is present in the brain, brainstem and cerebellum, and present throughout the spinal cord.

Grey matter is distributed at the surface of the cerebral hemispheres (cerebral cortex) and of the cerebellum (cerebellar cortex), as well as in the depths of the cerebrum (the thalamus; hypothalamus; subthalamus, basal ganglia – putamen, globus pallidus and nucleus accumbens; as well as the septal nuclei), cerebellum (deep cerebellar nuclei – the dentate nuclei, globose nucleus, emboliform nucleus, and fastigial nucleus), and brainstem (the substantia nigra, red nucleus, olivary nuclei, and cranial nerve nuclei).

Grey matter in the spinal cord is known as the grey column which travels down the spinal cord distributed in three grey columns that are presented in an "H" shape. The forward-facing column is the anterior grey column, the rear-facing one is the posterior grey column and the interlinking one is the lateral grey column. The grey matter on the left and right side is connected by the grey commissure. The grey matter in the spinal cord consists of interneurons, as well as the cell bodies of projection neurons.

-

Cross-section of a spinal vertebra with the spinal cord in the centre (and grey matter labelled).

-

Cross-section of spinal cord with the grey matter labelled.

Grey matter undergoes development and growth throughout childhood and adolescence.[3] Recent studies using cross-sectional neuroimaging have shown that by around the age of 8 the volume of grey matter begins to decrease.[4] However, the density of grey matter appears to increase as a child develops into early adulthood.[4] Males tend to exhibit grey matter of increased volume but lower density than that of females.[5]

Function

[edit]Grey matter contains most of the brain's neuronal cell bodies.[6] The grey matter includes regions of the brain involved in muscle control, and sensory perception such as seeing and hearing, memory, emotions, speech, decision-making, and self-control.

The grey matter in the spinal cord is split into three grey columns:

- The anterior grey column contains motor neurons. These synapse with interneurons and the axons of cells that have travelled down the pyramidal tract. These cells are responsible for the movement of muscles.

- The posterior grey column contains the points where sensory neurons synapse. These receive sensory information from the body, including fine touch, proprioception, and vibration. This information is sent from receptors of the skin, bones, and joints through sensory neurons whose cell bodies lie in the dorsal root ganglion. This information is then transmitted in axons up the spinal cord in spinal tracts, including the dorsal column-medial lemniscus tract and the spinothalamic tract.

- The lateral grey column is the third column of the spinal cord.

The grey matter of the spinal cord can be divided into different layers, called Rexed laminae. These describe, in general, the purpose of the cells within the grey matter of the spinal cord at a particular location.

-

Interneurons present in the grey matter of the spinal cord

-

Rexed laminae groups the grey matter in the spinal cord according to its function.

Clinical significance

[edit]High alcohol consumption has been correlated with significant reductions in grey matter volume.[7][8] Short-term cannabis use (30 days) is not correlated with changes in white or grey matter.[9] However, several cross-sectional studies have shown that repeated long-term cannabis use is associated with smaller grey matter volumes in the hippocampus, amygdala, medial temporal cortex, and prefrontal cortex, with increased grey matter volume in the cerebellum.[10][11][12] Long-term cannabis use is also associated with alterations in white matter integrity in an age-dependent manner,[13] with heavy cannabis use during adolescence and early adulthood associated with the greatest amount of change.[14]

Meditation has been shown to change grey matter structure.[15][16][17][18][19]

Habitual playing of action video games has been reported to promote a reduction of grey matter in the hippocampus while 3D platformer games have been reported to increase grey matter in the hippocampus.[20][21][22]

Women and men with equivalent IQ scores have differing proportions of grey to white matter in cortical brain regions associated with intelligence.[23]

Pregnancy renders substantial changes in brain structure, primarily reductions in grey matter volume in regions subserving social cognition. Grey matter reductions endure for at least 2 years post-pregnancy.[24] The profile of brain changes is comparable to that taking place during adolescence, a hormonally similar transitional period of life.[25]

History

[edit]Etymology

[edit]In the current edition[26] of the official Latin nomenclature, Terminologia Anatomica, substantia grisea is used for English grey matter. The adjective grisea for grey is however not attested in classical Latin.[27] The adjective grisea is derived from the French word for grey, gris.[27] Alternative designations like substantia cana[28] and substantia cinerea[29] are being used alternatively. The adjective cana, attested in classical Latin,[30] can mean grey,[27] or greyish white.[31] The classical Latin cinerea means ash-coloured.[30]

Additional images

[edit]-

Human brain right dissected lateral view

-

Schematic representation of the chief ganglionic categories (I to V).

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Purves D, Augustine GJ, Fitzpatrick D, Hall WC, LaMantia AS, McNamara JO, White LE (2008). Neuroscience (4th ed.). Sinauer Associates. pp. 15–16. ISBN 978-0-87893-697-7.

- ^ Kolb B, Whishaw IQ (2003). Fundamentals of human neuropsychology (5th ed.). New York: Worth Publishing. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-7167-5300-1.

- ^ Sowell ER, Thompson PM, Tessner KD, Toga AW (November 2001). "Mapping continued brain growth and gray matter density reduction in dorsal frontal cortex: Inverse relationships during postadolescent brain maturation". The Journal of Neuroscience. 21 (22): 8819–29. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-22-08819.2001. PMC 6762261. PMID 11698594.

- ^ a b Gennatas ED, Avants BB, Wolf DH, Satterthwaite TD, Ruparel K, Ciric R, Hakonarson H, Gur RE, Gur RC (May 2017). "Age-Related Effects and Sex Differences in Gray Matter Density, Volume, Mass, and Cortical Thickness from Childhood to Young Adulthood". The Journal of Neuroscience. 37 (20): 5065–5073. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3550-16.2017. PMC 5444192. PMID 28432144.

- ^ Luders, Eileen; Gaser, Christian; Narr, Katherine L.; Toga, Arthur W. (11 November 2009). "Why Sex Matters: Brain Size Independent Differences in Gray Matter Distributions between Men and Women". The Journal of Neuroscience. 29 (45): 14265–14270. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2261-09.2009. PMC 3110817. PMID 19906974.

- ^ Miller AK, Alston RL, Corsellis JA (1980). "Variation with age in the volumes of grey and white matter in the cerebral hemispheres of man: measurements with an image analyser". Neuropathology and Applied Neurobiology. 6 (2): 119–32. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2990.1980.tb00283.x. PMID 7374914. S2CID 23201991.

- ^ Yang X, Tian F, Zhang H, Zeng J, Chen T, Wang S, Jia Z, Gong Q (July 2016). "Cortical and subcortical gray matter shrinkage in alcohol-use disorders: a voxel-based meta-analysis". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 66: 92–103. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.03.034. PMID 27108216. S2CID 19928689.

- ^ Xiao P, Dai Z, Zhong J, Zhu Y, Shi H, Pan P (August 2015). "Regional gray matter deficits in alcohol dependence: A meta-analysis of voxel-based morphometry studies". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 153: 22–8. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.05.030. PMID 26072220.

- ^ Thayer RE, YorkWilliams S, Karoly HC, Sabbineni A, Ewing SF, Bryan AD, Hutchison KE (December 2017). "Structural neuroimaging correlates of alcohol and cannabis use in adolescents and adults". Addiction. 112 (12): 2144–2154. doi:10.1111/add.13923. PMC 5673530. PMID 28646566.

- ^ Lorenzetti V, Lubman DI, Whittle S, Solowij N, Yücel M (September 2010). "Structural MRI findings in long-term cannabis users: what do we know?". Substance Use & Misuse. 45 (11): 1787–808. doi:10.3109/10826084.2010.482443. PMID 20590400. S2CID 22127231.

- ^ Matochik JA, Eldreth DA, Cadet JL, Bolla KI (January 2005). "Altered brain tissue composition in heavy marijuana users". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 77 (1): 23–30. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.06.011. PMID 15607838.

- ^ Yücel M, Solowij N, Respondek C, Whittle S, Fornito A, Pantelis C, Lubman DI (June 2008). "Regional brain abnormalities associated with long-term heavy cannabis use". Archives of General Psychiatry. 65 (6): 694–701. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.65.6.694. PMID 18519827.

- ^ Jakabek D, Yücel M, Lorenzetti V, Solowij N (October 2016). "An MRI study of white matter tract integrity in regular cannabis users: effects of cannabis use and age". Psychopharmacology. 233 (19–20): 3627–37. doi:10.1007/s00213-016-4398-3. PMID 27503373. S2CID 5968884.

- ^ Becker MP, Collins PF, Lim KO, Muetzel RL, Luciana M (December 2015). "Longitudinal changes in white matter microstructure after heavy cannabis use". Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience. 16: 23–35. doi:10.1016/j.dcn.2015.10.004. PMC 4691379. PMID 26602958.

- ^ Kurth F, Luders E, Wu B, Black DS (2014). "Brain Gray Matter Changes Associated with Mindfulness Meditation in Older Adults: An Exploratory Pilot Study using Voxel-based Morphometry". Neuro. 1 (1): 23–26. doi:10.17140/NOJ-1-106. PMC 4306280. PMID 25632405.

- ^ Hölzel BK, Carmody J, Vangel M, Congleton C, Yerramsetti SM, Gard T, Lazar SW (January 2011). "Mindfulness practice leads to increases in regional brain gray matter density". Psychiatry Research. 191 (1): 36–43. doi:10.1016/j.pscychresns.2010.08.006. PMC 3004979. PMID 21071182.

- ^ Kurth F, MacKenzie-Graham A, Toga AW, Luders E (January 2015). "Shifting brain asymmetry: the link between meditation and structural lateralization". Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 10 (1): 55–61. doi:10.1093/scan/nsu029. PMC 4994843. PMID 24643652.

- ^ Fox KC, Nijeboer S, Dixon ML, Floman JL, Ellamil M, Rumak SP, Sedlmeier P, Christoff K (June 2014). "Is meditation associated with altered brain structure? A systematic review and meta-analysis of morphometric neuroimaging in meditation practitioners". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 43: 48–73. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.03.016. PMID 24705269. S2CID 207090878.

- ^ Hölzel BK, Carmody J, Evans KC, Hoge EA, Dusek JA, Morgan L, Pitman RK, Lazar SW (March 2010). "Stress reduction correlates with structural changes in the amygdala". Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 5 (1): 11–7. doi:10.1093/scan/nsp034. PMC 2840837. PMID 19776221.

- ^ West, Greg L.; Drisdelle, Brandi Lee; Konishi, Kyoko; Jackson, Jonathan; Jolicoeur, Pierre; Bohbot, Veronique D. (7 June 2015). "Habitual action video game playing is associated with caudate nucleus-dependent navigational strategies". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 282 (1808) 20142952. doi:10.1098/rspb.2014.2952. PMC 4455792. PMID 25994669.

- "Playing action video games can actually harm your brain" (Press release). Université de Montréal. 2017-08-07.

- ^ Collins K (10 August 2017). "Video games can either grow or shrink part of your brain, depending on how you play". qz.com. Archived from the original on 14 April 2018. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- ^ West GL, Zendel BR, Konishi K, Benady-Chorney J, Bohbot VD, Peretz I, Belleville S (5 May 2018). "Playing Super Mario 64 increases hippocampal grey matter in older adults". PLOS ONE. 12 (12) e0187779. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0187779. PMC 5718432. PMID 29211727.

- ^ Haier RJ, Jung RE, Yeo RA, Head K, Alkire MT (March 2005). "The neuroanatomy of general intelligence: sex matters". NeuroImage. 25 (1): 320–7. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.11.019. PMID 15734366. S2CID 4127512.

- ^ Hoekzema E, Barba-Müller E, Pozzobon C, Picado M, Lucco F, García-García D, Soliva JC, Tobeña A, Desco M, Crone EA, Ballesteros A, Carmona S, Vilarroya O (February 2017). "Pregnancy leads to long-lasting changes in human brain structure". Nature Neuroscience. 20 (2): 287–296. doi:10.1038/nn.4458. hdl:1887/57549. PMID 27991897. S2CID 4113669.

- ^ Carmona S, Martínez-García M, Paternina-Die M, Barba-Müller E, Wierenga LM, Alemán-Gómez Y, Cortizo R, Pozzobon C, Picado M, Lucco F, García-García D, Soliva JC, Tobeña A, Peper JS, Crone EA, Ballesteros A, Vilarroya O, Desco M, Hoekzema E (January 2019). "Pregnancy and adolescence entail similar neuroanatomical adaptations: A comparative analysis of cerebralmorphometric changes". Hum Brain Mapp. 40 (7): 2143–2152. doi:10.1002/hbm.24513. PMC 6865685. PMID 30663172.

- ^ Federative Committee on Anatomical Terminology (FCAT) (1998). Terminologia Anatomica. Stuttgart: Thieme[page needed]

- ^ a b c Triepel H (1910). Die anatomischen Namen. Ihre Ableitung und Aussprache. Mit einem Anhang: Biographische Notizen (3rd ed.). Wiesbaden: Verlag J.F. Bergmann.[page needed]

- ^ Triepel H (1910). Nomina Anatomica. Mit Unterstützung von Fachphilologen. Wiesbaden: Verlag J.F. Bergmann.[page needed]

- ^ Schreger CH (1805). "Synonymia anatomica. Synonymik der anatomischen Nomenclatur". In Fürth (ed.). Bureau für Literatur.[page needed]

- ^ a b Lewis CT, Short C (1879). A Latin dictionary founded on Andrews' edition of Freund's Latin dictionary. Oxford: Clarendon Press.[page needed]

- ^ Stearn WT (1983). Charles D (ed.). Botanical Latin. History, grammar, syntax, terminology and vocabulary (3rd ed.). London: Newton Abbot.[page needed]

External links

[edit]- May 2010, Stephanie Pappas (24 May 2010). "Why Is Gray Matter Gray?". Live Science.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)